By Jon Diamond

The interest in Brigadier Orde Wingate, founder and leader of the Commonwealth Chindits or Special Force, persists to this day, more than 75 years after his fiery death after his B-25 Mitchell bomber crashed in the hills of India.

Although his campaigns and causes ended with his death in March 1944, a posthumous attack was leveled against Wingate in a vituperative account of the Chindit leader’s contributions to the war in Burma. This appeared in 1961 in Maj. Gen. S. Woodburn Kirby’s The Official History of the War Against Japan, Vol. III: The Decisive Battles. Some have labeled this screed an “exercise in literary envy against unorthodoxy and creativity.”

Kirby’s Revenge

The animus between Wingate and Kirby went back to 1943, when the Chindit leader returned to New Delhi from Quebec and exhibited an aggressive and offensive stance in response to General Headquarters’ (GHQ) near total opposition to his plans for material and personnel requests for Operation Thursday, the nascent second Chindit invasion of Burma, which had received the approval of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS).

When Wingate flaunted his newly acquired access to Churchill, it humiliated Kirby, who was the director of staff duties at GHQ. In a complaint to Lord Louis Mountbatten, then head of Southeast Asia Command (SEAC), Wingate rashly named Kirby “as one of those who should be sacked for iniquitous and unpatriotic conduct.”

Thus, Wingate became a particular enemy of Kirby, who in 1951 was appointed to write The Official History of the War Against Japan. Kirby “took his revenge” on Wingate’s legacy with his pen, concluding his harangue with, “Although he served the Allied cause well by putting an almost forgotten army in the headlines and boosting morale, the very qualities which enabled him to win the support of the Prime Minister and the Chiefs of Staff and to create his private army in face of great difficulties reduced his value as a leader and a commander in the field.”

In regard to Field Marshal William Slim’s epic battle against Lt. Gen. Renya Mutaguchi’s Japanese 15th Army during their Operation U-Go invasion into Assam, India, in March 1944, Kirby wrote about the temporally coincident Operation Thursday in the Official History: “The operations of Special Force thus did little to aid Britain’s Fourteenth Army in defeating the [Imperial Japanese] 15th Army’s offensive. They had indeed the reverse effect, for the need to maintain five brigades of Special Force by air within Burma aggravated the shortage of aircraft which at times hampered Fourteenth Army’s conduct of the battles. Moreover, the fresh division [Imperial Japanese 53rd Division] which the Japanese brought into Burma, solely to assist in the defence of the Hukawng Valley and deal with the Chindits’ interruption of their communications to Mogaung and Myitkyina, was not required in full for that purpose and provided welcome reinforcements for the [Imperial Japanese] 15th Army.” To replace the 15th Army reserve, the Japanese Burma Area Army sent Mutaguchi only the 53rd Division’s 151st regiment.

Operation Thursday

Wingate’s expanded attack strategy for Operation Thursday was novel but realistic. Air power would revolutionize long-range penetration (LRP), which Wingate unveiled in mid-February 1943, as Operation Longcloth, as fighter-bombers became aerial artillery and the transports and gliders provided supplies, armaments, reinforcements, and casualty evacuation with precision, enabled by state-of-the-art radio communications conducted by Royal Air Force officers and enlisted men. Wingate’s Chindits would not need sea or land lines of communication. Unlike Operation Longcloth, Wingate envisioned Special Force being able to stay and fight at locales of choice rather than dispersing or having to fight their way back through an enclosing enemy.

The Chindit leader now coupled his tactical concept of movement with strategically placed proximate defended garrisons. Wingate was modernizing warfare by shaping his visions into realities in the remote and desolate Burmese theater, where an absence of roads, tremendous distances, and formidable terrain would make operations unsustainable as the Imperial Japanese Army was soon to learn in its U-Go offensive.

“The Motto of the Stronghold is ‘No Surrender.'”

The Chindits’ entry into Burma would be made by planes and gliders furnished by American Number 1 Air Commando led by Colonels Philip Cochran and John Alison. After the glider landing, roughly two columns of Chindits would occupy a field that would be converted into a landing strip for larger transport aircraft. Then the rest of the brigade would be brought in by the transport aircraft. Wingate envisioned that these defended areas or “strongholds” would be operational within 36 hours and ready to disrupt Japanese installations and communications in the vicinity.

This idea of a “stronghold” originated from Wingate’s canceled plan to establish one in March 1943, during Operation Longcloth, in the forests of Bambwe Taung. The notion was that such a defended locale with airfields, 25-pounder field artillery, 40mm Bofors antiaircraft artillery, and an internally located water supply would enable columns to retire into it for safety and then set out on raids from its perimeter. With supply and relief, these strongholds could become virtual offensives on their own. On February 20, 1944, Wingate was to document his notion of the stronghold, which was taken from the book of Zechariah: “Turn ye to the Stronghold, ye prisoners of hope.” Wingate added, “The motto of the Stronghold is ‘No Surrender.’”

As early as January 16, 1944, Wingate provided evidence to Mountbatten that a Japanese move up to the Chindwin River was a preparatory stage for a forthcoming offensive against Assam. He presciently stated that the Japanese would be compelled to use the “long bad vulnerable roads of Burma” for communication and that this offensive would be “strong and damaging and that before it was overcome, [British] 11th Army Group might have to face the temporary loss of all Manipur.” On March 14-15, the Japanese invaded Assam with three divisions from the north of Homalin and from the center of their Chindwin front, Operation U-Go.

Postwar opinions vary as to Wingate’s tactics, and many officers who fought alongside Wingate admired him for his field accomplishments rather than indicting him solely for his eccentric behavior. The Japanese also remember the effectiveness of Wingate’s planning and execution. In sharp contrast to the Official History, the consensus of these opinions will attest that the Chindits of Special Force greatly contributed to the eventual defeat of the Japanese 15th Army’s Assam offensive, which eventually led to their total abandonment of northern Burma and consequent losses of central and southern Burma to the British in late 1944 and 1945. Senior Japanese officers, among them Mutaguchi, the commander of the Japanese 15th Army and U-Go strategist, stated that Wingate’s Chindits during Operation Thursday drew off vitally needed units from the fighting at Imphal and Kohima and tipped that balance against them.

The Japanese Offensive Strategy

Initially in northern Burma, Mutaguchi commanded the formidable 18th Division from his divisional headquarters in Maymyo as a part of the 15th Army and was involved in the counterattack against the first Chindit assault, Operation Longcloth, in 1943. The British senior commanders in Delhi may have been derisive and willing to ignore any important outcome of Wingate’s first Chindit expedition (Operation Longcloth), but Mutaguchi later conceded that it had changed his entire strategic thinking.

Mutaguchi had scrutinized Wingate’s tactics and his use of the Burmese terrain and concluded, as Wingate demonstrated, that troops would be mobile with pack transport in northern and western Burma only during the dry season. Wingate had also shown that it was possible for units to attack across the main north-south grain of the rivers and mountains of Burma. The Japanese general’s own revelation, along with intelligence of the British buildup at Imphal, convinced Mutaguchi that he must eventually attack Imphal and Kohima to preempt another British offensive from India in 1944.

An advance into central Assam was beyond the capabilities of the Japanese in 1943. The Japanese, mainly owing to the influence of the first Chindit operation, had come to the conclusion that they would be unable to defeat this foreseen British offensive with a defensive mind-set and that an invasion of Assam to capture the Allied bases there was their best strategy. In late summer 1943, Mutaguchi began the planning for an offensive during the dry season of early 1944. However, prior to that invasion Mutaguchi argued that the 15th Army line of defense should be moved westward to at least the Chindwin River or even possibly to the hills on the Assam-Burma border.

A Three-Division Attack

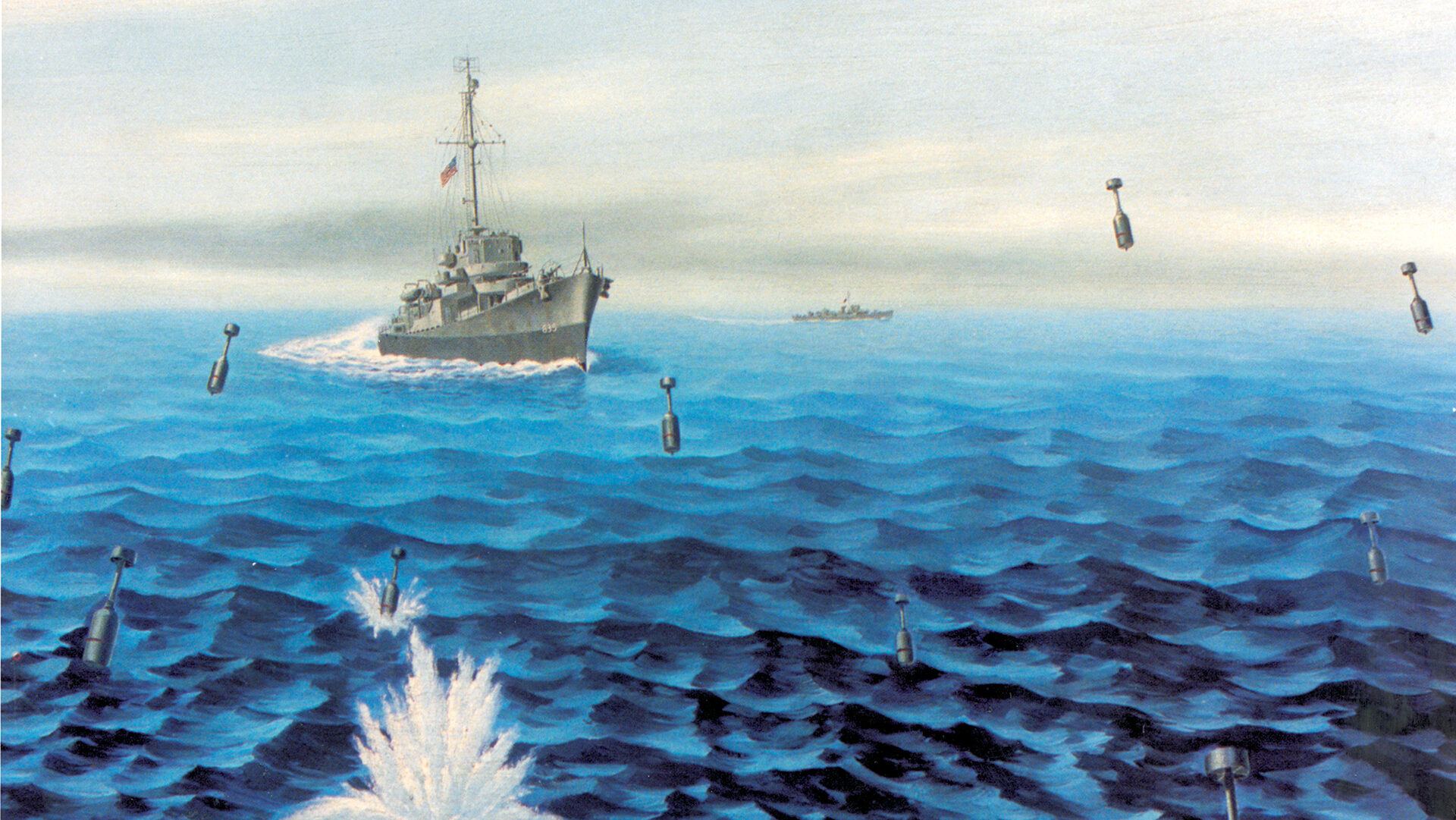

Thursday as a deep penetration behind

Japanese lines to disrupt enemy operations.

Upon being promoted to lead the 15th Army in March 1943, Mutaguchi maintained his headquarters in Maymyo and had under his command the 18th Division led by General Shinichi Tanaka, which faced the Chindits and Stilwell in the north; the 56th Division, facing Chiang Kai-shek’s Yoke Force in the east; and the 33rd Division facing the British on the Chindwin. The 15th Army was later reinforced by the 31st Division. Elements of the 31st Division began to arrive in Burma in June 1943, and this buildup was completed by September. It was this 31st Division that fought the British garrison at Kohima in India during the U-Go offensive in early March 1944.

Mutaguchi planned a three-division attack into India for March 1944 with the 33rd Division under General Yanagida advancing toward Imphal from the south, the 15th Division under General Yamauchi (with units of the Indian National Army recruited from Indian prisoners of war) attacking Imphal in two prongs from the east, and most significantly, the 31st Division under General Sato advancing to Dimapur, the huge supply base 11 miles long and a mile wide, which provided for the whole of the Slim’s Fourteenth Army.

Mutaguchi intended that as soon as Kohima and Dimapur were captured his victorious forces, accompanied by the Indian National Army and its leader, Subhas Chandra Bose, would advance into Bengal, where the subjugated Indian populace would mount an internal insurrection against British rule and support his triumphant “March on Delhi.”

Was Kirby correct in his Official History or did Special Force provide significant aid to Britain’s Fourteenth Army in defeating the Japanese 15th Army’s offensive? Mutaguchi had planned to move his tactical headquarters close to the Imphal front across the Chindwin River, but because of Operation Thursday there was a six-week delay. On April 9, 1944, a new headquarters, 33rd Army, was created and made responsible for north and central Burma, which included the area of Wingate’s second expedition.

Foiling Operation U-Go

On April 11, 1944, Mutaguchi was relieved of the responsibility of looking after northern Burma and was given the single task of the Imphal/Kohima offensive. It was not until April 20 that Mutaguchi’s headquarters reached the west bank of the Chindwin. Some have argued that Mutaguchi’s tardy arrival in Assam was of no consequence; however, a Japanese Defense Agency postwar manual on Operation U-Go highly rated the effectiveness of Wingate’s Chindits in causing this delay, which not only adversely affected the Japanese command structure in Assam but had an appreciable effect on decreasing the morale of the Japanese troops fighting the British Fourteenth Army.

Mutaguchi almost accomplished the aims of his U-Go offensive into Assam. If success had come to Mutaguchi’s campaign of March-June 1944, British and American forces operating in Burma would have had all of their contact severed with the West. An incorrect logistic and supply decision by this otherwise outstanding Japanese commander along with the selfless bravery of Indian and British troops thwarted his U-Go plan. Mutaguchi’s idea of commencing his offensive with only one month’s rations and supplies, in anticipation of capturing the stores at Dimapur, became a significant factor in his ultimate defeat. The Japanese had no equivalent to the American and British air supply capabilities to troops on the ground in fortified positions or on the move in the jungles and hills of Burma.

The Japanese generals’ reaction to Operation Thursday was discordant as their own U-Go offensive was underway. Mutaguchi initially believed that Wingate’s second operation was too far into the northern Burmese interior to affect his own operations in the Imphal/Kohima area. However, his superior, General Kawabe, took the Chindit assault seriously and cobbled together a force of about 20,000 troops to confront Wingate at Indaw in the spring of 1944. Initially, this force was able to prevent Brigadier Bernard Fergusson’s assault on Indaw, but it was then diverted to attack Lt. Gen. “Mad Mike” Calvert at the Chindit White City stronghold near Mawlu.

With the failure of his forces on the Assam front, Mutaguchi sacked his three divisional generals in the course of Operation U-Go against Imphal and Kohima. After it failed, he was next to go, and on August 30, 1944, he was transferred to the general staff in Tokyo. In a postwar letter to historian A.J. Barker, Mutaguchi wrote, “On 26th March I heard on Delhi radio that General Wingate had been killed in an aeroplane crash. I realized what a loss this was to the British Army and said a prayer for the soul of this man in whom I had found my match.”

As offered by historian Peter Mead, based on the responses of the Japanese officers who fought in Burma to postwar inquiries, “The airborne [Chindit] troops absorbed the greater part of the Japanese ground forces earmarked as reserve [for the Imphal offensive]….The operation of the Japanese 2nd Transportation Headquarters was completely frustrated by the airborne landings and by 16 Brigade [Fergusson at Indaw]. Neither 31st nor 15th Division [in Assam] received the additional supplies to provide for emergencies.”

The resupply of these two divisions of Mutaguchi’s U-Go offensive had been interdicted by Wingate’s Chindits. Japanese Monograph No. 134 corroborated this but also stated that the Chindits contributed decisively to the interdiction of supplies to the Japanese 31st, 15th, and 18th Divisions. Based on statements from over 30 Japanese commanders after the war, the monograph stated, “The raiding force [Chindits] greatly affected Army operations and eventually led to the total abandonment of Northern Burma.”

“He Was a Genius of War”

Just before his death in 1968, Mutaguchi wrote, “The advance into Burma of General Wingate’s forces at the time of the Imphal campaign brought about serious failures in the strategy of the Japanese Army…. At first I was unable to grasp the real nature of this enemy, and my immediate reaction was to assume that this was a unit sent forward as an irritant and made the mistake of thinking it could easily be swept away. However this forward unit was part of a large corps, going under the assumed name of the 3rd Indian Division [Special Force]. There were those among the [Burma] Area Army Staff who considered that in these circumstances we should call off the Imphal campaign, but I held that while the enemy was engrossed in this airborne operation he would be paying less attention to his rear and that this was a splendid chance to put our Imphal plan into operation….

“As we expected the plan was able to take the enemy unawares. The 33rd Division made a lightning advance to the Tonzang region, and the 31st and 15th Divisions which made up our main strength were able to cross the Chindwin without the enemy’s knowing…. However, after that, General Wingate’s airborne campaign spread more and more widely, and the [Burma] Area Army Commander [Kawabe] picked out the 24th Independent Mixed Brigade and a part of the 2nd Division to confront Wingate’s forces. The counterattack by these units on 25th and 26th March ended in failure. Then the Area Army Commander rushed the 53rd Division, the Strategic Reserve, to the Mawlu area [“White City”]. Further, the fact that we had no alternative but to use our feeble air force against these airborne forces was a very great obstacle to the execution of the Imphal campaign…. General Wingate’s airborne tactics put a great obstacle in the way of our Imphal plan and were an important reason for its failure.”

Major General Matsui wrote, “If Wingate decided on the timing of his operation, he was a genius of war.” A letter found on the body of a dead Japanese officer, retrieved from the National Defense Archives in Tokyo, said: “How was it that we Japanese were so triumphant in the beginning and had to endure the hell of failure in the end? What happened in Burma? In coming to any conclusion we must not forget Major General Orde Wingate…. He planted himself center stage and conducted all the fronts with his baton, which he called the Chindits. He reduced the Japanese power to wage war on four Burma fronts and so fatally affected the balance. In fulfilling this function alone, he showed himself a great general.”

Weakening the Japanese Thrust

Wingate’s brigadier and lifelong friend Derek Tulloch also cited Japanese Monograph No. 134, which praised Wingate’s developments in the art of warfare: “Although it was recognized that such an extensive drive by a tactical brigade into enemy territory was made possible only by air supply, Army Group commanders failed to correct their outdated conceptions of the British/Indian forces and the Chungking Army. Their failure to conceive a counterattack plan based upon the concept of close air/ground cooperation must be considered a great mistake.”

Tulloch further stated, “Wingate’s object was neither to kill nor contain Japanese soldiers, but to make the Japanese command conform to his will and so prepare the way for the victory of the Allied main forces. Purely by the action of positioning his brigades for the tasks he intended to carry out, he had already weakened the Japanese thrust at one of the three decisive points where he could not effectively control the battle. The morale of both Mutaguchi and his staff was thereby lowered to an appreciable degree.”

After the war, other high-ranking Japanese officers expressed their views on various aspects of the Burma conflict. The second Wingate expedition, Operation Thursday, took the Japanese by surprise. General Numata, Chief of Staff Southern Army, which was composed mostly of troops from conquered Southeast Asian countries, admitted that there were no Japanese plans to meet this airborne assault with the construction of strongholds.

A Devastating Factor in Cutting Lines of Communication

It was not until early April that the Japanese high command realized that a corps-sized, large-scale penetrating attack was underway. Until then, only local Japanese units were gathered to be hurled at the Chindits. Numata stated, “The reaction of the Japanese Army to this operation was so great that the Japanese 15th Army (the Army which included the three divisions detailed for the Imphal offensive) even thought of sparing from the force attacking Imphal a substantial force to annihilate the enemy unit and thus secure the safety of its rear. This plan was not carried out. Instead railway units and line of communication guards were collected and deployed against the British troops; while on the other hand 24 Independent Mixed Brigade, which was guarding the Moulmein area southeast of Rangoon against a possible sea landing, was ordered to proceed north at all speed. All those units were ordered to advance against the Allied airborne troops around Mawlu…. We became aware of its serious proportions only after the Japanese attacks were repulsed.”

General Naka, who at the time of Operation Thursday was chief of staff of the Burma Area Army, in response to questions as to whether the airborne forces upset the Japanese operations against Slim’s Fourteenth Army (Central Assam Front) or the Northern Combat Area Command (NCAC) front in the Hukawng and Mogaung River valley commanded by General Stilwell, stated: “This airborne operation had no direct effect on the Central Assam front, but it shortened our supply of reserves … it completely cut off 18th Division’s [opposing General Stilwell] supply route, thereby making impossible that division’s holding operation against the enemy in North Burma.”

General Numata observed, “The advance of the airborne forces did not cause any change in Japanese operational plans on either the Central Assam front or the NCAC front. Operations continued according to plan, but these airborne forces proved to be a devastating factor in cutting lines of communication. The difficulty encountered in dealing with these airborne forces was ever a source of worry to all the headquarters staffs of the Japanese Army, and contributed materially to the Japanese failure in the Imphal and Hukawng operations.”

Major Kaetsu, Naka’s general staff operations officer, added, “The big effect of the airborne operations was on the administrative situation of the main offensive into Assam…. The supply dump hidden in the jungle [for the Indaw-Homalin northern supply route to the Chindwin] was found by one of Bernard Fergusson’s RAF officers…. While the RAF officer in a light aircraft marked out the extent of the dump with smoke flares, USAAF Mitchells and Mustangs came again and again to wipe it out…. The 31st Division Infantry Group used the northern route on its initial advance on Kohima. It carried 21 days’ supplies initially. This group came through Ukruhl and cut the Kohima road to the south. The result of the northern line [Indaw-Homalin] going out and the consequent lack of food and ammunition for all of the 31st Division had a vital effect on the Kohima operation.”

Mutaguchi concluded, “The airborne landings were made during the night previous to the day on which we were to begin the Imphal operation. Some staff officers in the Burma Area Army were of the opinion that the Imphal operation should be temporarily suspended, but my resolution remain unchanged, and I carried out the operation as planned…. I was therefore not immediately concerned with this airborne threat, and I devoted myself to my previous intentions. It was a matter of great regret and concern to me that Burma Area Army switched one entire division [53rd Division] to cope with the enemy airborne force, especially at a time when the provision of one regiment of 53rd Division for the Imphal front might well have ensured the success of the operation.”

Preventing the Japanese From Tipping the Scales

As Michael Calvert, one of Wingate’s brigadiers for Operation Thursday, asserts, “It should be remembered that it was not the original task as laid down at Quebec for General Wingate’s force to assist the British Indian forces forward from Assam. The role given was to help General Stilwell with his Chinese American forces to take Mogaung and Myitkyina and an area south in order to allow communication through to China by road and thus keep China in the war.”

Thus, even though Wingate was not specifically tasked with directly assisting General Slim in Assam, his strategy of interdicting Japanese supply routes, in particular the Indaw-Homalin route to the Chindwin River, with his roving Chindit columns supported by their strongholds, enabled Special Force to indirectly tip the scales of victory toward Slim as the effects of diminishing manpower, dwindling ammunition, and starvation took their toll on Mutaguchi’s troops during Operation U-Go.

According to Sir Robert Thompson, who served with Wingate during Operation Thursday as a senior RAF officer, “It has been easy enough to list the Japanese units and manpower drawn off by the Chindits which otherwise might have been used to reinforce the attack on Imphal. In total it may not seem much (probably equivalent to a division and a half) but at times it was touch and go both at Imphal and Kohima. Any extra forces or reinforcements could have tipped the scales and given Mutaguchi the victory…. If there had been no Chindit landings all the divisions in Imphal would have been in the bag, the Assam airfields would have been lost and China might have collapsed.”

Orde Wingate: Brilliant Commander or Convenient Excuse?

In conclusion, Wingate’s supporters interpreted the evidence of statements by Mutaguchi and other senior Japanese officers that Operation Thursday drew off vitally needed units from the fighting in Assam and contributed to the defeat of the U-Go offensive by disrupting lines of communication and hampering distribution of rations to troops that possessed only a meager three-week supply. To this day, Wingate’s critics counter that these Japanese officers were touting Operation Thursday as a success in order to provide an excuse for their defeat.

Is the author of this article suppose to be Jon Diamond?

Kirby may have been partially correct in his assessment but it matters little. Wingate accomplished one indisputable result. He kept the Japanese that he opposed off balance. It should be remembered that the Japanese had two objectives; control territory in Burma and Assam and foment rebellion in India. They failed at both thanks to Wingate and the somewhat more conventionally organized Gen. Slim. In retrospect, it is easy to see how initial Japanese victories over both the US and Britain gave them a false sense of superiority which eventually led to their defeat.