By Brian Geeslin

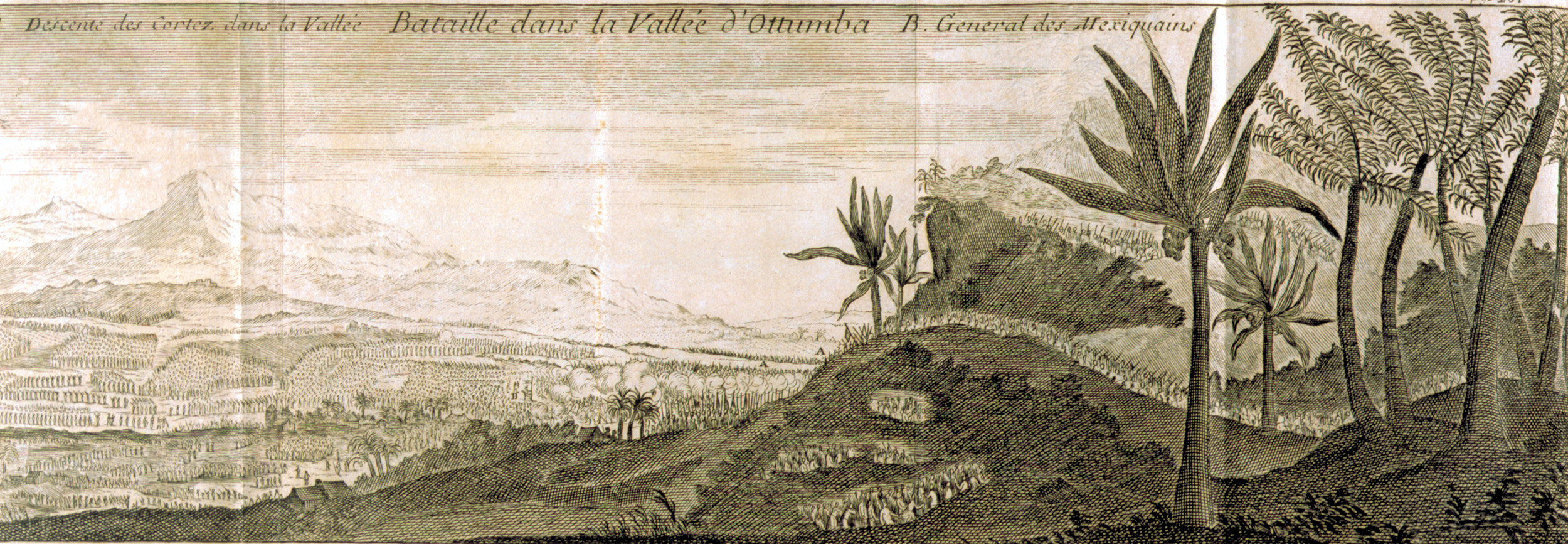

In the morning hours of July 8, 1520 Hernando Cortés, with the remnants of his army of Spanish adventurers and Indian allies, neared the crest of mountains overlooking the plain of Otumba (the Spanish corruption of the Nahuatl name of Otompan), an Indian city dominating the valley along Cortés’s line of march. Spanish scouts brought him reports of a large body of Aztec warriors in the valley ahead. Indeed, bands of Aztecs had been taunting them to hurry along all through the morning. As the army of Cortés reached the crest they saw spread out below an immense host filling the depth of the valley and giving it the appearance, from the white cotton armor of the Indian warriors, of being covered with snow.

Cortés and his supporters were retreating toward Tlascala, the homeland of his most loyal allies, and had been doing so for the previous seven days; all that time they were harried front and rear by bands of Aztec warriors and, in one such instance, Cortés, always in the fore of battle, received a severe wound to the head.

The Spanish and their allies had little food and water, a situation that had not changed in several days. But the hardships of the march, which were shared by Spaniard and ally alike, helped to form a more cohesive group. In one skirmish, two Spaniards and one horse were killed while foraging for food. The horse was eaten as a feast and the march continued with Cortés imposing tighter discipline to prevent more losses. He even forced the severely wounded to carry their own weight, since the horses were wearing out from carrying double riders.

The small army pushed toward its destination in a circuitous route, avoiding the more populous areas, so that after a week on the march they were actually less than two days’ journey from their point of departure at the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan. They dared not retread their steps for fear of what lay behind, for a week earlier the Spanish and their allies had been disastrously expelled from Tenochtitlan on Noche Triste, “The Night of Sorrows.”

Aztec mythology promised the return of Quetzalcoatl, a deified priest-king who had been banished in the remote past but one day would return as prophesied. Upon the arrival of the Spanish many Aztecs, including Montezuma, believed that the Europeans were children of the Sun who would pave the way for Quetzalcoatl’s return; thus the Spanish were invited to the capital. Spanish abuses, however, changed this view and led to the Night of Sorrows, instigated when the Europeans attacked the celebrants of a religious festival.

In the ensuing struggle, the Spanish lost about 430 killed or missing, many of whom drowned while trying to swim, laden with gold, from the lake-encompassed city. Their allies’ losses numbered in the thousands. In addition to human toll there were 77 horses—their most important weapon—all of their arquebuses, cannon and gunpowder, and all but 12 of their crossbows. Cortés’s remaining army numbered about 440 Spaniards, of whom 20 were mounted, and perhaps two thousand Indian allies. With this small body of men, Cortés prepared to face as many as 100,000 Aztec warriors. Perhaps not since Thermopylae had such odds been faced more resolutely.

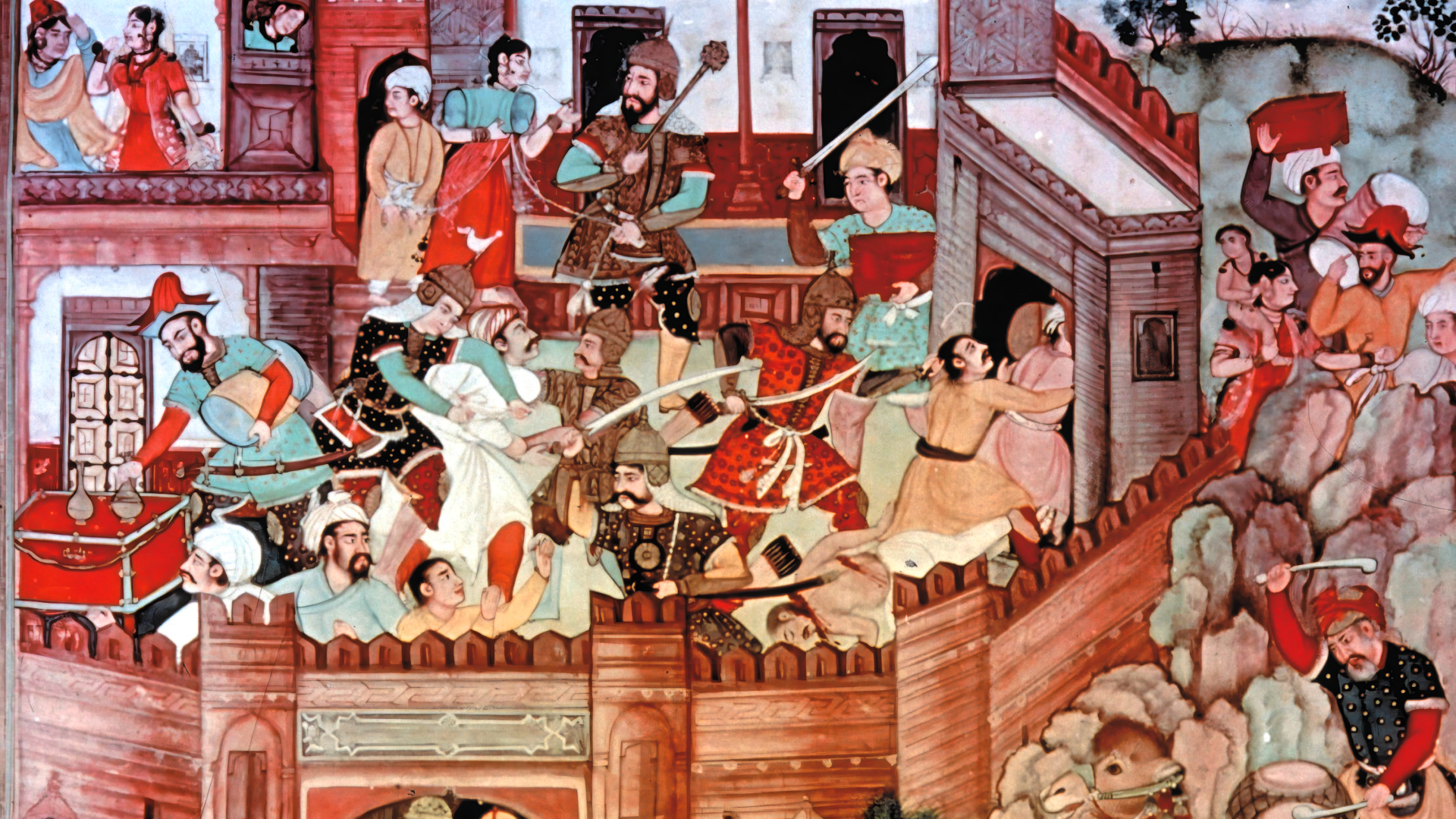

To the Aztecs, war was an economic, psychological and religious necessity; they believed it was their destiny to conquer—a chosen people whose mission was to nourish the gods with the human blood that alone could sustain them in their cosmic battle against the forces of darkness. For this reason, one of the main objectives in war was to take captives who would later be sacrificed. The braver and higher in rank a captive, the more valuable he became, because the Aztecs also practiced ritual cannibalism whereby the eater would absorb the virtues of the eaten.

Thus Aztec warfare never entirely lost its ceremonial character, partly explaining why the Spanish were not wiped out on the Night of Sorrows. For the type of limited war Aztec warriors waged they were almost invincible.

The Aztec’s main offensive weapons were the macana, a 3 1/2-foot-long, paddle-shaped, wooden club edged with sharp bits of obsidian; and obsidian-tipped javelins hurled by means of an atlatl, which added range to the throw. The macana was a brutally effective weapon when used to its full potential and on more than one occasion Spanish horses were beheaded in a single stroke. Other weapons included the sling, spear, bow and arrow, and lance, most of which had obsidian heads, though some were tipped with copper.

The Aztecs also used a dart-type weapon with a three-pronged head that was attached to a leash so that after impact the dart would inflict a frightful wound by being yanked out by the attached cord. For defense the Aztecs carried a shield 20 to 30 inches in diameter made of a wooden frame covered in hide, which the privileged classes decorated with paint and feathers appropriate to their rank and status.

Body armor was commonly used by all who could afford it. Made from quilted cotton soaked in brine and formed into a tight-fitting suit about two fingers thick, the “armor” covered the body from neck to knee. In fact, this armor was so effective against javelins and arrows that the Spanish often adopted it as the lighter and cooler alternative to their own steel armor. The elite warriors also wore masks and headdresses made of wood and leather that signified their rank, but these were decorative in nature and were of little or no defensive value.

The Aztecs possessed no standing army but youths began military training at age 15, learning the use of various weapons, and although there was no group drill in the European sense, each participated in sham maneuvers during monthly ceremonials. When called upon for duty, each new recruit would follow an experienced warrior into battle. Warriors received no pay but it was through the military that men advanced to more desirable positions in civilian life, and if someone distinguished himself in battle he could receive gifts of slaves or property from a chief or king. Moreover, any soldier who captured four prisoners in battle gained automatic entry into the ruling class as an Arrow Knight.

The basic Aztec military unit was a squad of 20 men formed into larger units of two, four or eight hundred warriors, commanded at each level by members of the knightly orders of the Arrow, the Jaguar and the Eagle.

The largest Aztec formation numbered eight thousand warriors commanded by a chief or king. Each leader carried a banner with a glyph as an organizational device. Tenochtitlan provided 20 contingents of elite warriors while each allied city or tribe mustered an army of its own, so that in all the Aztecs had the potential to field an army of 200,000 warriors. But these numbers were deceiving.

The Aztecs did not possess the support system necessary for prolonged warfare due to the fragile balance of their agrarian-based economy. The capital was parasitic in nature, consuming a great deal of the available commodities while producing no food and little beyond military and luxury goods. Yet warriors could not live off the land while on campaign because the political system was based on a complex of treaties with allied and conquered peoples by which each remained theoretically independent. Finally, the Aztecs had no reliable beasts of burden; each warrior had to pay for his own supplies and carry them, or hire a servant, or be wealthy enough to own slaves.

In any campaign longer than a few days, Tenochtitlan had to carry out negotiations to arrange for supply markets in the areas the army marched through, so that the warriors could purchase the necessary and luxury goods they were accustomed to having. Obviously an extended or distant campaign was a difficult undertaking and impossible to keep secret. Early in Montezuma’s reign, 16,000 Aztec warriors were killed while on a campaign in the mountains of Michoacan. The Aztecs were vulnerable in many ways, suffering defeats and setbacks, but they were tenacious in the pursuit of their religious, economic and political goals—which were more or less the same.

The Aztecs did not develop the concepts of tactics and strategy beyond the rudimentary levels, due to the ceremonial nature of war as well as the difficulty of carrying out extended campaigns and the set nature of most battles, which were usually fought on flat, open ground. Moreover, Aztec wars were usually short, often decided by a single battle. They were not used to long campaigns that they now faced against the Spanish, with the continual mobilization of warriors and the drain on morale and the economy.

Traditional Aztec battles began with a great deal of noise as each army shouted, clashed weapons and beat drums. Then volleys of slingshots, arrows, javelins and other missiles were discharged as the two armies rushed toward each other. Next was hand-to-hand combat, generally a free-for-all in which the weight of numbers decided the battle.

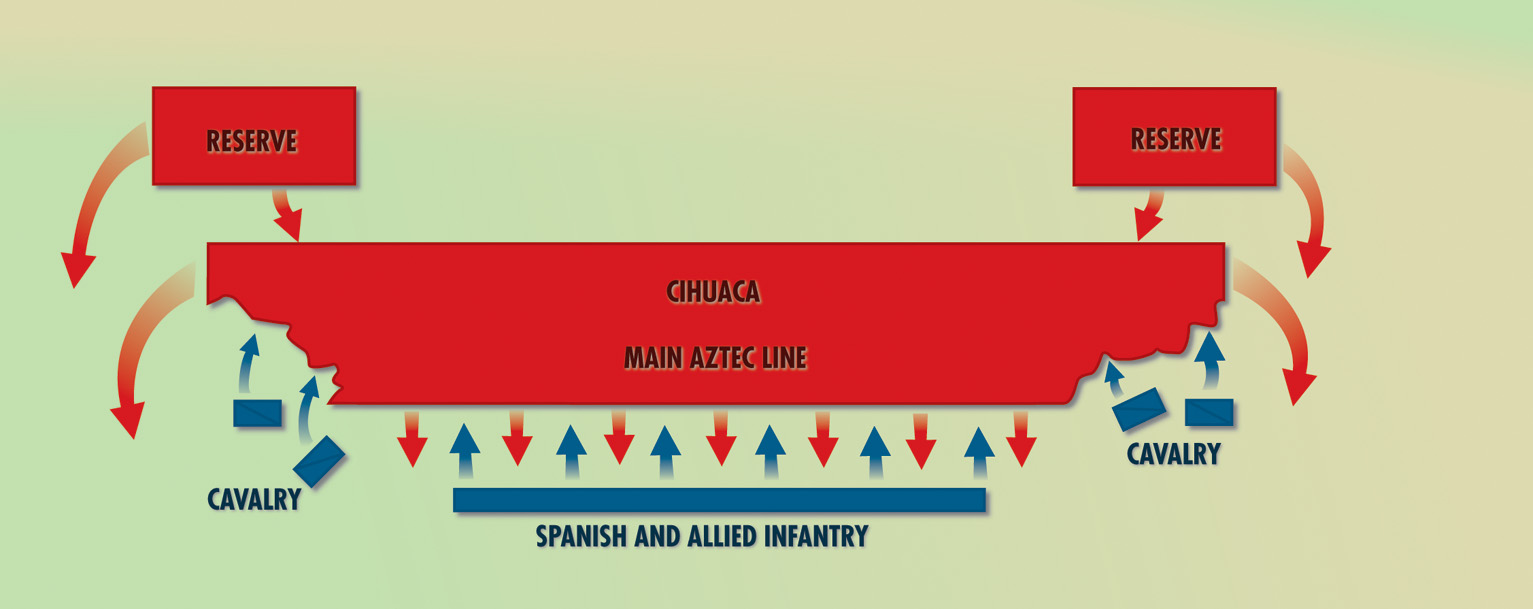

At Otumba the Aztec leader was counting on numbers, for though Cortés and his men had defeated many Aztec armies, they had never faced such a multitude. A less seasoned army might have succumbed to despair; a less resolute commander might have parleyed, but from the beginning Cortés had relied upon his panache and charisma to carry himself and his army through all adversity. As Cortés faced the seemingly impossible odds awaiting him on the Otumba plain he leaned more heavily than ever before upon these nebulous qualities to carry his plans to fruition.

Cortés had been brought up and trained in the religious and military milieu of the Reconquest, a phenomenon that infused into the Spanish character a source of mission; it has been said that “in Spain the cross is on the sword.” The Reconquest of the Spanish peninsula from the Moors had taken more than seven centuries and when finally achieved in 1492 by Ferdinand and Isabella the die of Spanish history was cast, or warped, by the experience. The Catholic Church promised instant acceptance into Heaven to any Christian soldier who died in battle against the infidel, and that spoils of war were considered an acceptable reward for making life in the here and now more comfortable. With the assurance of immortality, individual prowess and faith became keystones in the edifice of the ideal “Christian Soldier.”

Gold is a strong motivator for even the most pious individual and even more so for a soldier of fortune. Cortés’s Spanish troops were simply that—soldiers of fortune—for most owned nothing except what they gained by the sword. (One such soldier was Bernal Diaz, whose memoirs are invaluable and a classic of historical literature.)

After the Moors had been expelled from Spain the militant character thus created would not just wither away in a country that had been at war for centuries. Besides, who would soil his hands with menial labor when marching off to war offered a greater and far nobler reward. Fresh fields of conquest in the New World relieved the Old World of a good portion of its rowdy, unchained, trouble-making elements whose main motivation was greed or need legitimized as religious zeal. The soldiers themselves certainly did not see it in that way, for them Church and State were not a dichotomy, nor were religious duty and material rewards. The soldiers under the command of Cortés were a hardy breed inured to the hardships of military life, professional soldiers living on the fringes of the known world. In their minds they had everything to gain and nothing to lose.

Spanish military techniques had evolved to accommodate the new technologies and tactics of the time. By 1520 the arquebus and cannon were in common use but each of these weapons required a cumbersome, regimented process for firing—in same time an experienced archer could loose perhaps 20 aimed arrows. Firearms were only effective when employed in large numbers, and Cortés’s arquebusiers made up only 15 percent of his very small army.

In battle with the Aztecs, firearms produced unpredictable results. In one of their early engagements the Spanish let loose a volley of cannon and arquebusier shots into an attacking group of warriors, who responded by throwing dust and leaves into the air to hide their dead, then charged again without giving the Spanish time or room to perform the complex regimen for a second volley. The Spanish were saved by their discipline and hand-to-hand fighting abilities, and by the timely use of their cavalry. The importance of firearms in the conquest has been much exaggerated and Otumba is proof. It was one of the largest battles fought in the New World prior to the 19th century and is conspicuous for its lack of firearms. There the Spanish did not possess any scientific superiority of arms; what they did have was bravado, experience, courage and faith in their cause.

The average Spanish soldier in the New World was armed with a sword for both hacking and thrusting, and a buckler. Many also carried a lance or halberd. The crossbow had been in use in Europe for centuries, its small shaft could penetrate steel armor at 20 yards or more. The Aztecs had no defense against it. At Otumba, however, there were not enough to make a difference. The common soldier wore steel armor over his chest and back, greaves to cover the front of his legs, and a steel helmet. It is unlikely that any of the Spanish had full body armor, in spite of some of the codex illustrations, given the climatic conditions, the social station of the soldiers, and the fact that it provided no positive military function—it impeded movement and increased fatigue to intolerable levels. Most of the Spanish adopted the native cotton armor.

The horse deserves credit beyond the firearms, crossbow, and, in many instances, the abilites of the Spaniards, for it was with the horse that often gave the Spanish the courage to do battle. Cortés early on realized the importance of this animal and usually employed it to the greatest possible effect. Without the 20-odd horses at Otumba the Spanish would have perished to a man.

Cortés’s skill was more diplomatic than military; it was his Byzantine talents that put him at the head of an army in the New World, and these same talents kept him there throughout the many misfortunes his army endured during the now famous, or infamous, expedition. In battle he merely performed as any other Spaniard, which was exceptional under the circumstances. Cortés’s ability as a general was conventional for the time, yet more often than not merely mediocre. He often led his men to fight on unfavorable ground, or otherwise subjected them to ambushes and like misfortunes that could have been prevented under a commander with more military foresight; if nothing else, Cortés was smooth talking and charismatic.

In diplomacy, intrigue and the other politics of war, Cortés took advantage of every situation, often turning a setback into an advantage. Such was the case when Navarez was sent with a large force to relieve Cortés of command and put him under arrest. Cortés ultimately subverted the command structure of this huge armada and made its army part of his own. Without these additional troops, the toppling of the Aztec state would have been impossible.

The Spaniards were the minority in Cortés’s army; at Otumba less that one in every ten combatants was European. The Tlascalans, like the Spanish, were used to hardship for they had been in a continuous state of war for decades. the Spanish and allies were never fighting at odds greater than two or three to one, and within these parameters the Spanish had the advantage of movement that comes with the discipline of professionals against militia-type troops. The press of Aztec warriors in the rear upon those in front would have made their fighting more difficult since the macana was a “two-handed-sword,” and the press from the rear increased the effect of every Spanish blow. Each time an Aztec leader fell his men lost heart, thereby fighting with less zeal, less determination and far less faith in his cause.

And the Spanish had one very significant advantage, one ally without whom they would have almost certainly become one more band of adventurers that perished in the search for El Dorado: The smallpox virus.

Cortés was fortuitously enforced in 1520 by the largest armada set to sail in the New World. This fleet was sent by the governor of Cuba to bring back the renegade Cortés and his ragtag army but the arriving army was infiltrated, overrun and defeated in a night attack by Cortés, who persuaded nearly all of the newcomers to join him, swelling his army. Most of these men, however, would be killed through the vicissitudes of the campaign before the battle of Otumba. Several men among the reinforcements were carrying common European viruses, the most dangerous being smallpox, but most of the Spaniards were immune, having already survived the illness.

The native population had never even experienced the common cold before the arrival of the Spanish but after April 1520 smallpox spread in exponential proportions until it became pandemic. In part it was the smallpox epidemic that prevented the Aztecs from destroying the Spaniards after their expulsion from Tenochtitlan. Within hours the leader of the Aztec resurgence was dead of the disease along with hundreds of others every hour, including many of the elite warriors. The burden of the battle rested on the people from the territory of Texcoco, Saltocan, Otumba and the surrounding countryside.

Contagion was little understood at the time and plagues were attributed to the will of God, or the gods, in both Europe and the New World and many of the Aztecs began to believe they had made a mistake, that they had offended the gods. The psychological effect on the Indians was undoubtedly devastating to morale; conversely the Spanish were all the more convinced that it was their Christian duty to destroy the Aztec state and eradicate their pagan culture from the face of the earth. And so as the battle raged, the Aztecs, unsure of themselves for the first time in centuries, fell back before the Spaniards, preferring to pelt them from a safe distance with missiles.

Diaz writes, “We were surrounded by shouting Mexicans who fell on us with their darts, arrows, and slings.” At this point the captain Sandoval shouted, “Today gentlemen, is the day on which we are certain to win. Trust in God, and we shall come out of this alive, and to some purpose!” This simple rallying cry greatly encouraged the common soldiers, all of whom were on foot and could not see the progression of the battle. The soldiers relied upon expostulations of this sort from their commanders to rally men at a weak point in the line or simply to steel their courage at such desperate times as they were in at that moment, for the situation was grim.

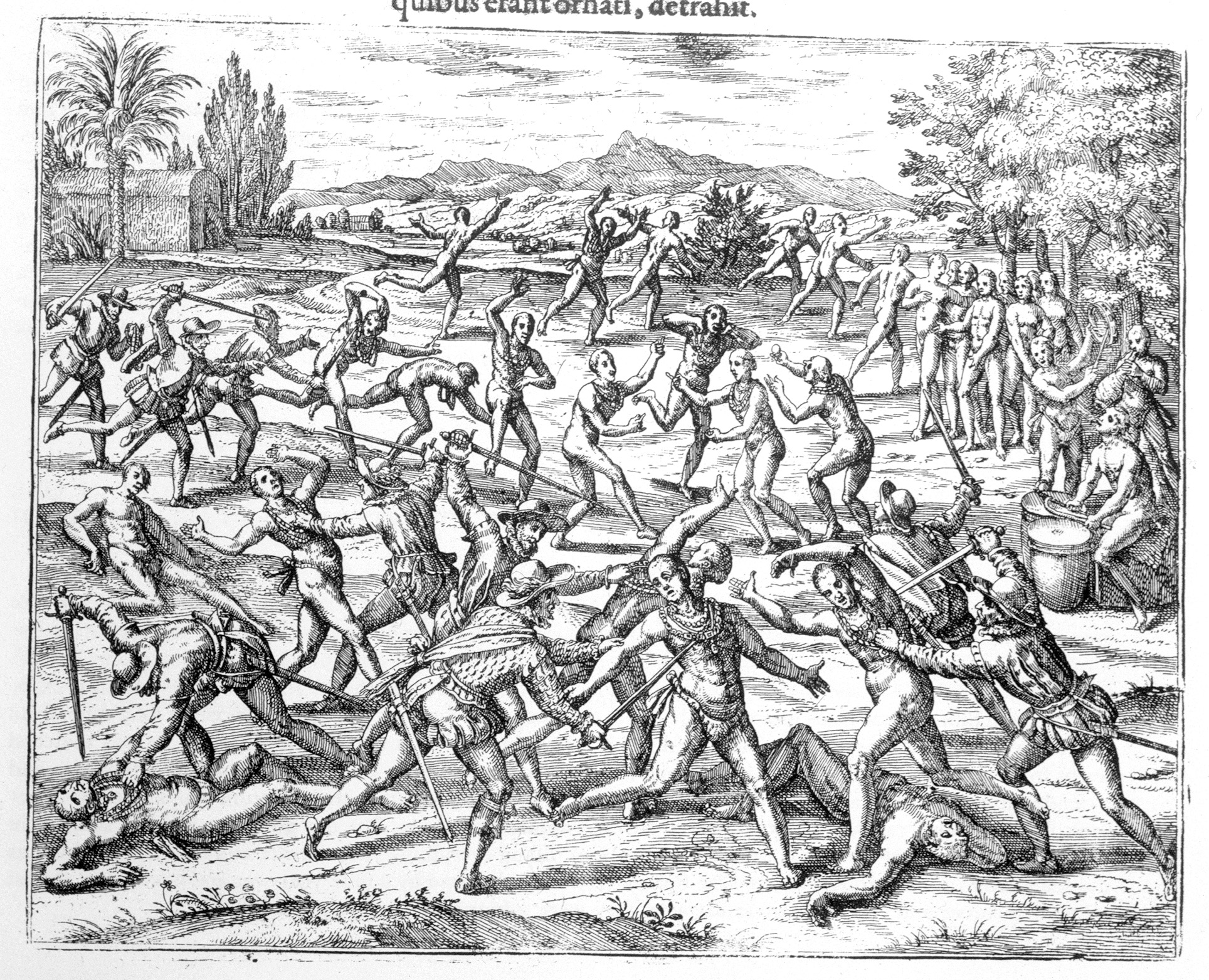

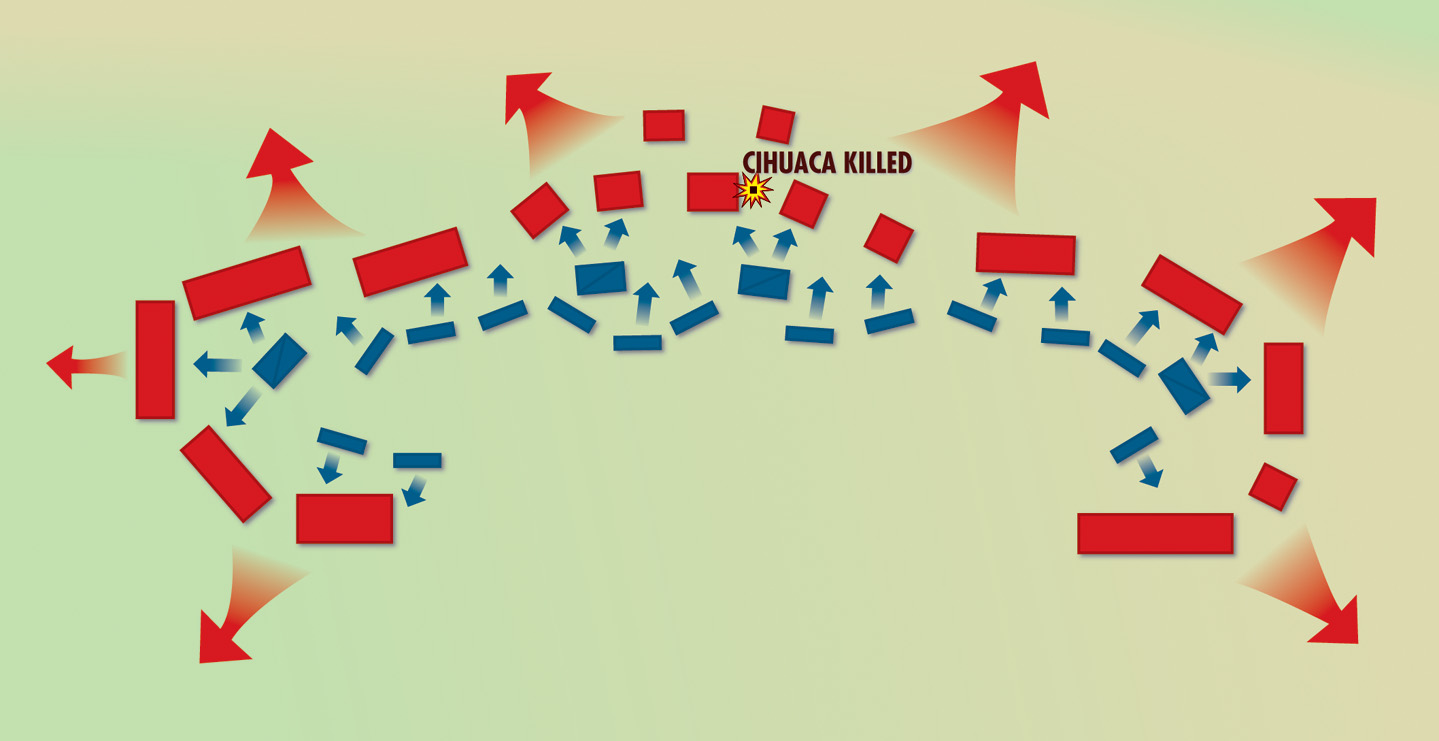

As the Spanish and allies neared the point of hopeless exhaustion, Cortés, standing in the saddle, caught sight of a fabulous plumb among the masses that surged around him; he shouted to those horsemen nearest him, “There is our mark! Follow and support me!” and together they charged their weary horses into the press of fighting and pushed toward the banner of bright feathers. The horsemen charged down on the Aztec commander, who was carried in a litter, and killed his retainers who had not fled before them, but it was not Cortés who killed the Indian commander; Juan de Salamanca decided the battle by putting his lance through Cihuaca. At this point the Aztec command structure broke down as panic began to spread through the Aztec ranks with an inexplicable rapidity and the army was routed. As the Aztecs panicked many lost their weapons, or turned their backs to the enemy while attempting to flee, and this as well as the inherent immobility in large bodies of men allowed the Spanish and Tlascalans to take full advantage of the situation. The way the Spaniards exploited a rout is graphically recorded by an Aztec chronicle:

“They attacked all the routed, stabbing them, spearing them, sticking them with their swords. They attacked some of them from behind, and these fell instantly to the ground with their entrails hanging out. Others they beheaded: they cut off their heads, or split their heads to pieces.

“They struck others in the shoulders, and their arms were torn from their bodies. They wounded some in the thigh and some in the calf. They slashed others in the abdomen and their entrails all spilled to the ground. Some attempted to run away, but their intestines dragged as they ran; they seemed to tangle their feet in their own entrails. No matter how they tried to save themselves, they could find no escape.”

Nor were the allies to be discounted, for Diaz writes that “the Tlascalans became like very lions. With their swords, their two-handed blades, and other weapons which they had just captured, they fought valiantly and well.”

The battle had been decided. It was one of the most decisive battles that was ever to be fought in the New World; the sources record 20,000 Aztecs killed. As far as the participants were concerned it was the most desperate encounter and it “was only by God’s Grace” that they were victorious. The number of chiefs and nobles killed was extremely high and a great deal of booty fell to the Spanish in gold ornaments and armor, rare plumes, shields and other items of value, perhaps offsetting the great wealth that had been lost while fleeing Tenochtitlan on the Night of Sorrows.

In spite of Spanish bravery and prowess it was still only by luck that Cortés managed to spot the Aztec commander who had been thrown by chance into range of the Spaniards, for without Cihuaca’s death the battle would have been an Aztec victory with Cortés’s army annihilated. Certainly the Aztec Empire would have been decimated by smallpox and other Old World diseases but they may have accommodated themselves to the new situation.

As it turned out, after three weeks of rest and recuperation, Cortés returned to a Tenochtitlan still racked by a smallpox epidemic, after lesser ordeals of reconsolidation and a campaign to pacify any cities that might support Tenochtitlan in the projected siege. When Cortés returned he was reinforced with more wayward Spaniards as well as Tlascalan and other Indian allies in spite of the fact that smallpox had become pandemic. The rest is history—but not for the field of Otumba it would have been a different history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments