By Allyn Vannoy

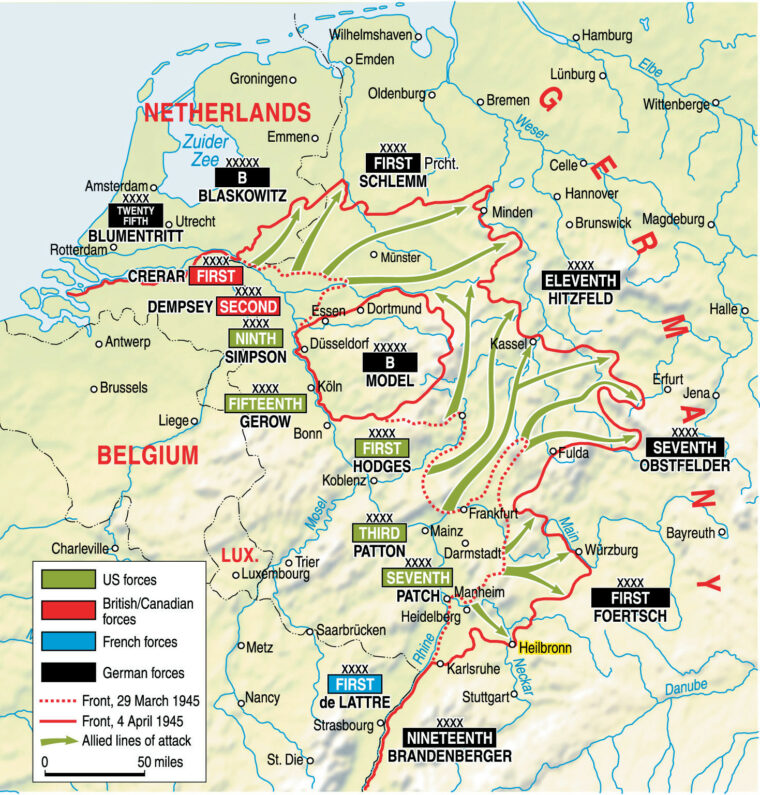

Following its swift advance to the Rhine, the American 100th (Century) Infantry Division resumed its pursuit of retreating German forces. On the morning of March 31, 1945, elements of the division crossed the Rhine between Ludwigshafen and Mannheim and headed straight into the heart of Germany. The war in Europe was in its last throes, but there was still plenty of action to come.

After passing through Mannheim, the division fanned out to the south. The 399th Infantry Regiment, on the right flank, headed toward Hockenheim to establish contact with the II French Corps. On the left was the 397th Infantry, with the 398th Infantry in reserve. The 10th Armored was out in front of the division, with the French coming up on the right. The units moved with all possible speed to prevent German forces from reorganizing. Roadblocks and blown bridges formed the only appreciable German resistance.

The advance continued on April 2, rolling toward Heilbronn, a city with a pre-war population of 100,000. Located at the head of the Neckar valley, Heilbronn was well situated, with roads leading south to Stuttgart and east toward Ulm, the much-vaunted German “National Redoubt.” On April 3, the Germans relinquished the town of Neckargartach, on the west bank of the Neckar River just north of Heilbronn, to the 10th Armored after a stiff rear-guard action. The Germans withdrew across the river into the city’s factory district, blowing the bridge over the river after them. Since the French advance was lagging behind, the 399th was detailed to guard against a possible counterattack on the exposed right flank and rear.

The city of Heilbronn, on the east bank of the Neckar River, now lay open to the American division. As a key rail and communications center, the Germans could be expected to defend Heilbronn to the end. The city was an ideal spot for a last-ditch defense. The deep, swift-flowing Neckar River was a formidable barrier. The three road bridges and one railroad bridge leading into the city had been blown. Forming a semi-circle behind the city was a group of easily defended hills with thick woods that afforded excellent concealment for German artillery and an unbroken line of observation to the river. Despite several previous bombings, the city was relatively intact. The thick stone walls of the numerous factory buildings functioned as miniature fortresses. Beneath the buildings was a labyrinth of tunnels. The city was a focal point for many battered Wehrmacht units that were regrouping, as well as numerous local Volksturm units.

A quick study of the ground convinced the 100th Division commander, General Withers A. Burress, that Heilbronn was pivotal if the Germans hoped to stop the American advance toward their strongholds in the mountains of southern Germany. With the division’s right flank still seriously exposed due to the lagging French, Burress decided against encircling Heilbronn from the north and south. Instead, he chose to throw the main strength of the 100th across the Neckar near Bad Wimpen, north of the city, swing south across the Kocher, and come at Heilbronn from the rear with the 397th and 398th Regimental Combat Teams. The 399th was to move directly toward Heilbronn and hold the enemy in place while protecting the division against attacks from the south.

The plan started coming apart almost as soon as it was created. On the afternoon of April 3, while the division was still about 24 kilometers from the Neckar River, Burress was forced to detach one infantry battalion and rush it forward to join the 10th Armored Regiment, already near Heilbronn, to assist in establishing a bridgehead. Accordingly, the 3rd Battalion, 398th Infantry, advanced into Neckargartach and took up positions along the river 300 yards north of a blown bridge. To avoid alerting the Germans, the crossing was to be made without artillery preparation. At 3 am on April 4, Company K crawled into assault boats and made the crossing without firing a shot.

The infantry swiftly fanned out and formed a bridgehead. Before them loomed the silhouette of an enormous power plant. Members of the battalion’s Raider platoon, leading the advance, began drawing sniper fire. Taking cover along the river bank, they returned fire and waited for Company K. The entire force then advanced into the deserted power plant. Despite the fact that the Germans had been alerted, Company L successfully made the crossing, followed by Company I. Within an hour, the entire battalion had navigated the river and assembled in and around the plant.

The Germans Suddenly Launched a Counterattack Along the Entire Battalion Front with a Force of Between 500 and 1,000 Men

At dawn, Companies K and L, each supported by a platoon of heavy machine guns from Company M, moved toward their objectives. Company L was to branch out to the north and occupy a group of lumberyards situated along a rail line, while Company K was to advance south about 300 yards to the edge of the factory district and then turn east along the Neckargartach Bridge road and advance into the hills southeast of the town. The 1st Platoon was assigned the mission of taking Tower Hill, a height whose steep, barren slope, devoid of cover, was topped by the skeleton of an old tower. The 3rd Platoon was to take Cloverleaf Hill, directly south of Tower Hill, while the 2nd Platoon was to clean out a glassworks just south of the crossing site. Company I, meanwhile, was to dig in on a line parallel to the river about 300 yards in front of the power plant.

By 9 am, the advance was well under way. Company L moved forward some 500 yards to the northeast, skirted a large, water-filled ditch about halfway to the lumberyards, and reached the railroad and the highway that ran alongside it at the junction with the Neckargartach road. On Company L’s right, the 1st Platoon, Company K, began to climb Tower Hill. At the same time, the 2nd Platoon entered the factory district to the south, and the 3rd Platoon advanced to the south along the road paralleling the river on the far side of the factory district.

While all the troops of the battalion were in motion, the Germans suddenly launched a counterattack along the entire battalion front with a force of between 500 and 1,000 men. The Germans, having infiltrated the American lines through underground passageways, appeared in a building on the northern edge of the factory district behind the 2nd Platoon. Another force appeared east of the highway and cut off the platoon struggling up Tower Hill. A third group attacked Company L and the 3rd Platoon along the highway. From the lumberyards to the north, a fourth German force caught the men in the center of the 3rd Battalion front in a withering crossfire with the force in the factory buildings to the south.

Lieutenant Almon Brunkow, commanding a section of heavy machine guns attached to the 3rd Platoon, was hit when he walked out onto the road to reconnoiter a new position for his guns. As Brunkow lay helpless in the open, Private Leland L. Zeiter and other members of his machine gun squad made an effort to reach the fallen officer, but enemy fire was too intense. The platoon was forced withdraw north to the railroad bridge at the junction of the Neckargartach road. There, together with the elements from Company L, the Americans made a gallant attempt to hold out against attacks from three sides. Outnumbered and facing the possibility of being surrounded, the GIs were forced to withdraw in small groups to Company I’s position in front of the power plant. The 1st Platoon on Tower Hill and the 2nd Platoon in the factory district were now isolated.

American mortars and artillery, which had been unable to provide fire support due to the close proximity of friendly forces to the enemy, now began shelling the Germans. With the help of this support, the battalion regrouped and succeeded in regaining some of the lost ground, advancing across the open field to its front. Company L was on the left rear of Company I, and Company K, now numbering only 20 men, protected the right flank. Intense fire continued to blanket the field that the battalion was advancing across, but with effective artillery and mortar support, the battalion managed to push forward.

As a result of the attack, 3rd Battalion found itself on a line along the far edge of the water-filled ditch that Company L had passed earlier in the morning. There the battalion prepared to make a stand. By now, it was evident that the German forces in Heilbronn were far stronger than anyone had anticipated. From the lumberyards to the north and the factories to the south, German reinforcements were pouring into the area. Their artillery, emplaced on hills to the east, poured intense fire onto the Americans below. To make matters worse, the 10th Armored Regiment had failed to construct a promised pontoon bridge behind the 3rd Battalion, and the accurate German artillery fire made forward movement dangerous, if not suicidal.

Despite the enemy fire, the 1st Platoon advanced to the top of Tower Hill before daybreak, surprising and capturing several Germans. In the fierce fight that followed, the outnumbered platoon was cut off. Despite a shortage of ammunition, Lieutenant Alfred J. Rizzo radioed that he was confident they would be able to hold out and work their way back to the battalion after nightfall. The last word from the platoon was a request for fire on an enemy gun to the east that was giving them trouble. A group of Raiders tried to reach the platoon after dark, but was unable to cross the highway. Meanwhile, the platoon, although outnumbered and surrounded, fought fiercely until its ammunition was expended, throwing hand grenades at the Germans as they closed within a few yards. A German officer said later that it took all 90 men of his company to subdue the Americans.

To add to the division’s problems, word was received that the 10th Armored had been relieved and was being shifted to the north flank of VI Corps, presumably to take advantage of a gap there that would allow them to approach Heilbronn from the rear. This left Burress with a staggering tactical problem—one of his battalions was on the east side of the Neckar, under attack by a superior German force. Any attempt to withdraw the battalion would be disastrous. Burress, therefore, abandoned his original plan of attack and began rushing the 397th Infantry across the Neckar. At 2 pm on April 4, the 2nd Battalion, 397th Infantry, began crossing the Neckar. By 5:40 pm, the battalion was on the right bank, having negotiated the crossing without casualties.

Immediately after landing on the east bank, Company E pushed toward the factory district. The company advanced through a breach in the concrete wall along the factory district’s northern perimeter, and headed for the first factory, a red-brick building 200 yards away across an open loading yard. The advance was made in the face of heavy crossfire from the factory and a building to its left. Once at the factory doors, the men in Company E had little difficulty convincing the few Germans who had remained inside the structure to surrender. The factory building to the left, a former glassworks, where a considerable size force of Germans was holed up, was more troublesome. Hugging the perimeter wall, the 3rd Platoon crawled toward the sturdy, red-brick building. Despite heavy machine gun fire, one squad battled its way into the structure, but the rest of the platoon was unable to move forward. The squad inside the factory slowly fought its way through the building until just before nightfall, when they were joined by Company F.

54 Casualties in a Single Night for Company E

Having cleared out the first two factory buildings, the GIs turned their attention to two shell-pocked houses on the right and slightly behind the first factory building. Unable to approach the nearest house directly because of intense enemy fire, members of the 3rd Platoon crawled along a catwalk to the rear of the house. From there, with fire support from the 1st Platoon, who had remained behind the concrete wall, they cleared the structure. Darkness halted further operations. Company F remained in the factory next to the wall in the northeast corner of the factory district, and Company E bedded down in the battered house they had just captured. Their situation remained precarious since the Germans were still in the second house across the courtyard.

During the night the two companies came under attack. Company E was forced to attempt a withdrawal. The 2nd and 3rd platoons managed to get back over the catwalk to the factory, where they joined Company F. The 1st Platoon, together with the mortar men of the Weapons Platoon who had joined the company earlier, was less fortunate. Sergeant Thomas Convery, in command of the 1st Platoon, although wounded, ordered his men to withdraw as best they could to the Company E command post across the loading yard. Most of the men were wounded, but somehow they managed to fight their way across the Neckargartach road to the command post. In all, Company E suffered 54 casualties that night.

Meanwhile, a large German force attacked the 2nd Battalion in the glassworks. Armed with a considerable number of panzerfausts, the Germans took a heavy toll. Lieutenant Carl Bradshaw, Company F commander, decided to call on the big guns for help. Waiting until all elements, with the exception of Company F, had withdrawn, Bradshaw called for artillery support. He directed the fire of 8-inch guns so effectively that the German were thrown into confusion and broke off their assault.

To the north, the 3rd Battalion was having its own difficulties. Attacked by a determined force along its 500-yard front, the battalion beat back repeated assaults. Several of the German attacks were led by panzers, but with the support of two tank destroyers and two Shermans tanks, which fired from the left bank of the Neckar, the battalion fought off every effort to drive them back. The 3rd Battalion was also assisted by accurate fire from the 374th and 242nd Field Artillery Battalions. Performing yeoman service was the Raider Platoon—nine men armed with machine guns—which held the battalion front north and east from the water-filled ditch.

After dark, Company A, 31st Engineers, attempted to complete a treadway bridge and assemble rafts capable of carrying tanks and tank destroyers to the east bank. German artillery concentrations on the bridge site were so accurate that the project had to be abandoned, but the engineers grimly continued efforts to assemble pontoons. Silhouetted by fires in Neckargartach and the factory district, 14 engineers were hit by shellfire. Each attempt to launch pontoon floats was met with uncannily accurate artillery fire that punctured the floats and caused additional casualties. Because of the continued German shelling of the river bank, no attempt at building a bridge was made the next day. Fog oil was used as a smoke screen over the river, providing sufficient cover to allow a trickle of supplies to be ferried across in small boats.

Companies F and G attacked again before dawn, moving south. Company F, surging out of the factory building in which it had spent the night, took over the factory between it and the building that Company E had taken the previous day. While reconnoitering for a suitable way out of the first factory building, Lt. Bradshaw, Company F commander, was killed by a sniper. The company, having found an easier way, left the building, moving to the in-between factory and later to Company E’s factory, where they waited for Company G to move up from their positions beyond the concrete parameter wall to join the drive.

Throughout the morning, Company F engaged in a firefight with the Germans in the loading yard north of the buildings. The shacks and loading platforms provided excellent cover for the Germans in the yard, and it was difficult to fire on them, because their comrades covered them from the two neighboring houses Company E had occupied the night before. Company G, advancing with the 2nd Platoon, did not know that there were Germans in the loading yard. As they ran across the field in front of the concrete wall, a burst of machine gun fire wounded one man. Gaining the protection of the wall, the platoon lay behind the bank on which the wall was built and formed a skirmish line, preparing to attack through the railroad gate at the northern end of the loading yard.

Sergeant Dalton Yates was surprised to see a German stick a gun barrel through a hole in the wall. That was their first indication that there were Germans on the other side. The platoon began to toss grenades over the wall into the enemy’s laps. The Germans returned the compliment with potato-masher grenades of their own. For the next few minutes a lively game of catch ensued over the six-foot-high wall. Some of the Company G men moved to fire at the Germans through holes in the wall. One man opened a gap in the wall with a grenade, and another helped enlarge it with his rifle butt. Looking through the hole, they saw some 40 Germans well dug-in in the loading yard, some 15 yards away. By this time, six men of the 2nd Platoon lay dead, and Lieutenant John Slade, seeing that something drastic had to be done, called for mortar fire on the Germans in the yard despite their proximity to his own troops. The 60- and 81-mm mortars opened up, while the men of the 2nd Platoon hugged the earth in a shallow depression just behind the wall.

After several minutes of bombardment, the Germans lost interest in continuing the fight. Leaving their holes, they ran toward Slade’s men with their hands in the air, crying, “Komerad!” Six of the Germans were shot by their own officers as they attempted to give up, but another 37 poured through the railroad gate into the hands of the 2nd Platoon, weeping, bleeding, and screaming hysterically.

The loading yard cleared, the 2nd Platoon prepared to attack its original objectives, the two houses just to the right of the factory where Company F was waiting. Meanwhile, efforts were being made to bring reinforcements into the bridgehead. With artillery fire all along the river still too intense to build a bridge or construct a large raft or ferry, the only way across the river was by assault boat and small rafts. In the absence of tanks, Lt. Col. Gordon Singles, commanding the forces in the bridgehead, called for artillery fire. Particularly bothersome to the men crossing the loading yard were two long warehouses that ran north and south along a lagoon on the western edge of the factory area. Accordingly, 155-mm guns of the 373rd Field Artillery blasted the entire length of the warehouses. The two houses which had caused so much trouble for Slade’s platoon were reduced to shambles, and the two huge warehouses were set afire.

Although German artillery still commanded the city and both banks of the Neckar, the American artillery countered using excellent observation points on the ridge along the western bank of the river, supplemented by artillery observation aircraft. At 11 am on April 5, Companies I and L crossed the river without casualties and prepared to join the fight. Following an artillery and mortar preparation on the loading yards that blasted out the diehard Germans entrenched there, the assault was resumed at 2:45. Company F moved through the factories the 2nd Battalion had reduced in the previous day’s action and made contact with Company G and the remaining men of Company E. Moving cautiously ahead, Company G pressed on to the two burning warehouses. In the warehouses the men found 100 Germans still dazed from the artillery fire. The enemy surrendered without a fight.

Company G waited in position until Companies I and L caught up with them. Meanwhile, Company F mopped up the few remaining buildings in the glassworks and advanced to a small grove of trees at the southern tip of the works. Company I, on the left, pushed to the Fiat automobile plant on the eastern edge of the glassworks and cleared the building in the face of intense machine gun and panzerfaust fire. Company L guarded the left rear of the advance, extending the line of the 3rd Battalion south from the Neckargartach road to the Fiat plant. Company K, having crossed the river in the meantime, stood in reserve.

Blocking the advance to the south was a large open area that provided the Germans with a clear field of fire. In the center of the area, approximately 200 yards south of the grove of trees held by Company F, was a gray stone and concrete house, situated at the junction of the railroad spur connecting the glassworks to the city. A key spot, the junction was a natural defense point. Waiting until dark, four riflemen and a medic from Company F crept out from the grove and made their way along the railroad track toward the stone house. After the first group had advanced some 20 yards, a second squad followed. Suddenly, a German machine gun opened up from a window of the house, killing all five men in the lead squad. Realizing that the building was too strongly defended for a frontal assault across open ground, the second group withdrew to the grove. It was decided to put off the advance until the next day.

Shortly After Ordering the Retreat Lieutenant Kirkland was Killed by a Sniper

While the 2nd and 3rd Battalions were battling the Germans, Company G moved north to cross the Neckar at Neckarelz, where the 63rd Division had thrown a bridge across the river. Late on the afternoon of April 5, the 1st Battalion prepared to cross the Neckar and establish a second bridgehead in the center of the city. Using assault boats, Company C was put across at 6:30 pm. While the crossing operations were being conducted, German artillery hit the west bank and snipers fired from the buildings north and south of the crossing site. On the east bank, however, German opposition was negligible, as the boats swung north to land near a large brewery. Advancing toward the brewery after landing, the 2nd and 3rd platoons drew increasing fire from the structure, but had little difficulty in taking the building and the 40 young Germans defending it.

At dusk, Company A made the crossing, and joined Company C in the brewery for the night. At about 4:30 am, Company B crossed, and by daylight the battalion was ready to fan out and expand its bridgehead. Company A was given the mission of moving north to relieve the original bridgehead. Companies B and C were to fan out and protect the right and rear of Company A and widen the bridgehead sufficiently for the engineers to throw a span across the Neckar. Company A advanced through two dense city blocks to Kaiserstrasse, the street leading to the center bridge of the three over the Neckar that had been blown by the Germans. Now in the heart of the city, they began running into the core of the German resistance.

The American strategy was to expand the second bridgehead and form a pincer with the northern bridgehead on the center of Heilbronn. Company C, guarding Company A’s right and rear, pushed two blocks east of the Flein road, running south from the center of Heilbronn. Company B, on the right, advanced east to the road and took the sugar refinery south of the brewery, as well as a few apartment houses, meeting only scattered sniper fire. But the right flank of Company B, along the line of the sugar refinery and the Knorr works southeast of the refinery, was dangerously exposed. In the afternoon, a patrol from Company B was forced to re-enter the sugar refinery and clear it of infiltrating Germans, while the rest of the company prepared to clean out the Knorr works.

Before they could launch their assault, however, the Germans counterattacked. Swarming through narrow alleys between the houses, German infantry supported by four panzers charged the American positions. Company A, which had been trying to extend its right flank beyond Kilianskirche, a large church two blocks east of the river, was forced back to its original positions. Company C, fighting along the Flein road, came under savage attack, but managed to hold its positions despite having two panzers assault its right flank. Sergeant Pittman Hall was on the second floor of an apartment house on the corner when the German panzers struck the company’s positions. Firing a bazooka, he disabled the main gun of one panzer. Meanwhile, an artillery forward observer zeroed in 8-inch guns on the panzers, causing both to beat a hasty retreat.

Company B was the hardest hit by the German counterattack. The GIs had set up a strongpoint in an apartment house on the west side of the Flein road, across the street from the Knorr works. Two panzers, together with two platoons of infantry, came up the Flein road from the south. Private B.R. Smith fired on the enemy force with a light machine gun, killing or wounding some 20 to 30 of the infantrymen. The Tigers kept coming, but by the time they had reached within 150 yards of the Company B position, 8-inch shells were falling around them. The American line, however, was not strong enough to withstand the fire of the Tigers, and Lieutenant Owen Kirkland, company commander, ordered a withdrawal. Shortly after he gave the order, he was killed by a sniper.

The company withdrew to a line along the northern edge of the sugar refinery. The two Tigers came after them, but as they moved into the open field before the refinery, the American artillery began to find the range, forcing them to leave. In the interim, a liaison plane took off to over fly the area and direct artillery fire. The plane, with Lieutenant R.W. Sands serving as pilot and Sergeant Richard Hemmerly serving as observer, chased the Tigers. A direct hit was scored on one with an 8-inch shell, and a near-miss caused a brick wall to collapse on the other, damaging it heavily.

Meanwhile, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, finding that they could not attack the gray stone house frontally, initiated a four-pronged drive to link-up with the 1st Battalion. Sergeant Harold Kavarsky led the attack with his squad from Company I. They made it to the first row of warehouses without drawing fire, but when the artillery was shifted, the Germans fired on them from the cellar of the westernmost warehouse and from foxholes in front of the house. Kavarsky withdrew his men and called for renewed artillery. For 30 minutes shells fell on the warehouse in front of the gray house, killing 15 Germans as they tried to escape. Kavarsky then set up two light machine guns on the second floor of the warehouse and sprayed the windows of the warehouses in the second row and the enemy foxholes.

Kavarsky and his men ran the 50 yards to the middle building, reached the ramp leading up into the first floor, and fired a machine-gun burst into the windows of the building before entering the structure. As they waited, a round of their own artillery struck the building, hitting Kavarsky in the leg. Four men led by Sergeant John P. Keelen went down into the cellar and captured five prisoners. In the cellar they found a tunnel leading from their warehouse to the westernmost warehouse in the row—the one nearest the gray house. The group proceeded through the tunnel to the next warehouse and found it deserted. From the upstairs window they could see the cement bunker between them and the house. They fired four bazooka rounds into the bunker, killing two Germans and causing those in the foxholes to retire into the house.

Early in the afternoon, Company F came down into the last warehouse to finish the job of taking the gray house. Sergeant Joseph A. Snyder leaned out of the window and fired two rifle grenades into the window of the house at the same moment that some Germans were putting out a white flag. Meanwhile, the GIs worked through the buildings around the house, taking 20 prisoners from the house itself and 53 from the factory across the street. With the second German strongpoint in American hands, Companies I and F found comparatively easy going. They advanced four companies abreast, Company G on the right, next to the river, Companies F and I in the center, and Company L on the left. Company K covered the left and rear of the advance. That night, they cleared the block below the gray house.

On the following day, they worked down 550 yards of the next block. Company L continued down the block into a group of shell-torn apartment houses, but as they entered the buildings they were met by a heavy burst of machine-gun fire from across the railroad tracks 100 yards to the east. As the 1st Platoon moved into the southeasternmost building, they were attacked from the east by a small force, but the platoon held its ground. Although it was growing dark, the Germans continued to fire into the corner apartment house. From the roofless top floor of the building, Private Arthur Nimrod fired his BAR down on the railroad tracks, keeping the Germans from crossing the tracks and attacking the apartment houses in force.

The intensity of the American assault on Heilbronn continued to increase in fury. During the night of April 6-7, Company C of the 399th Regiment crossed the river and was attached to the 1st Battalion, 397th. The members of the 399th spent the night in the sugar refinery, waiting for dawn, when they would attack the Knorr works, which had been recaptured by the Germans. At 8:30 am, however, the Germans struck first with more than 100 infantry supported by three panzers and a flak wagon. The attack came from the south, moving around the Knorr works toward the southern flank of Company B. One of the panzers rolled up to the crossroads directly between the sugar refinery and the Knorr works and fired a few rounds before being driven off by artillery.

The counterattack threatened to cut off the men of Company C. The Germans had infiltrated along the east side of the sugar refinery in which Company C was battling and around the rear of the building to the river. If the German force was there in strength, Company C would effectively be isolated from the rest of the troops at the bridgehead. Sergeant James Harte, using an eight-man patrol, eliminated the threat. In the meantime, Company C suffered two more counterattacks, one at noon and another shortly afterwards, but beat them back. The two companies then moved out to attack. Company C captured the Knorr works for the second time with little difficulty, and Company B, also facing negligible opposition, reestablished positions on the Flein road that it had been forced to abandon earlier.

The bridgehead was now secure, but the purpose of the crossing, to relieve the northern bridgehead, had not yet been accomplished. Company A found that it could not move north from Kilianskirche without armored support. Assault boats continued to operate on the Neckar River throughout the day and night. On the morning of April 6, the boats were moved north 400 yards to a new site at the ruins of a foot bridge where Company A, 397th, had cleared the east bank. However, the Germans infiltrated behind the company’s lines and fired on the engineers and on the landing site, harassing operations to such an extent that tanks from Company C, 781st Tank Battalion, and tank destroyers from Company B, 824th Tank Destroyer Battalion, were brought down to the river bank to fire on the houses the Germans were using. This did not stop the enemy artillery, however, which kept finding the engineers and forcing them to move their site.

Private Hare Smashed the Front Door with the Butt of His Rifle and Seven Germans Rushed out and Surrendered.

Under cover of darkness, the indefatigable engineers of Company C, 31st Engineers, began to build a treadway bridge 100 yards south of the demolished span. At daylight, smoke generators were put to use screening the engineers. As part of the plan, three small generators were ferried across the river to the east bank so that if the wind shifted to the west, the crossing would still have cover. The generators, skillfully concealed in rubble or placed deep in cellars, produced smoke in puffs that diffused quickly, leaving no telltale sign of the source. By evening the treadway bridge was nearly completed and tanks and tank destroyers lined the bank ready to roll across. Then, at 5:30 pm, German artillery thundered ominously and five floats were knocked from under the bridge.

That night, as fewer German shells fell along the river banks, the engineers were able to rebuild the bridge, completing it by daybreak. Before 8 am on April 8, 24 tanks from Company C, 781st Tank Battalion, and nine tank destroyers from Company B, 824th Tank Destroyer Battalion, crossed over to the east bank and joined the infantry. Traffic was still pouring across the bridge when the wind fishtailed, leaving the bridge perfectly visible. At 11:30 am, German shells knocked out two floats, reducing the carrying capacity of the bridge to 10 tons. Two hours later, the bridge was underwater again. The division went back to supplying the troops in the bridgehead via assault boats.

On the morning of the eighth, Companies G, F and L, 397th, had to hold up their advance while Company I cleared a group of Germans from an orchard in their sector. From a small brick house in the southeast corner of the orchard the Germans could fire on the factory in which Company F was preparing to conduct attacks on the southern part of the factory district. Along the east side of the orchard was a long factory, with all but half of its first floor blown away. In the center of the orchard, a German machine gun was emplaced in a dugout where the trees were sparse enough to afford good lanes of fire.

Sergeant Richard C. Olson led his squad of the 2nd Platoon, Company I, across the road into the factory. From there they planned to work along the walls on the inside of the battered building to a point opposite a red-brick house. They had to keep low behind the walls of the factory because the machine guns in the house would fire on them every time they raised their heads. The first scout, Private James Van Danne, climbed over a sheltering wall and made it into the next room. Private Henry P. Perkins didn’t make it. As he followed Van Danne over the wall, a sniper from the brick house killed him. At the same time, machine guns in the orchard opened up on the Company I men, forcing them to rush for cover.

Olsen got two bazookas into firing position. Sergeant Edward Eylander, leader of the 2nd Platoon, placed two light machine guns in windows in the factory across the road and opened fire. Several bazooka rounds and an anti-tank grenade quieted the fire from the house, and a smoke round from one of the bazookas forced the machine gunner from the center of the orchard. After a heavy preparation burst of machine gun fire from positions across the road, Sergeant Thomas E. Cooper led four men across the orchard and up to the front door of the house. Private Arthur Hare smashed the front door with the butt of his rifle and seven Germans rushed out and surrendered.

After Company I had cleared the orchard, Company L advanced into the block of factory buildings to the left of the orchard. The company moved through the block with little difficulty until reaching an office building at the southern end of the block next to the junction of two rail lines. From the railroad station at the junction, the Germans zeroed in their machine guns, pinning down the company. American artillery registered 12 direct hits on the building, silencing the enemy machine guns and enabling Company L to continue into the next block of factories.

By noon on April 9, the American forces in the north bridgehead were ready to cross the railroad tracks, move into the heart of Heilbronn, and hook up with the troops pushing up from the south. Only 1,000 yards away, the tall spire of Kilianskirche could be seen rising out of the smoke. That night, the bridging engineers constructed a motor-powered pontoon assault ferry capable of transporting tanks. Assembling five floats, they loaded them onto trucks, transported them to the river bank, and by 6:30 am had the ferry in the water. For once, the German artillery did not bother them, and by 11:30, 13 tanks and tank destroyers, in addition to the 81-mm mortar platoon of Company D, 399th Regiment, had been carried across the river.

While the first pontoon bridge had been coming under artillery shelling, the 1st Battalion, 399th, was moving across the river to take positions in the southern bridgehead facing south and east. Company C was already across and helping the 1st Battalion, 397th, protect and expand the bridgehead. Company B crossed the river on the pontoon bridge and took positions on the right of the 397th. The remainder of the company negotiated the crossing in assault boats, digging in on the right flank of Company B.

At the southern bridgehead, Company A, 397th, had been stopped on the afternoon of April 6 along the east-west road running along the north side of Kilianskirche. There the Germans put up the most furious defense during the entire battle for the city. Company A had been advancing with its 2nd Platoon on the left next to the river, and 3rd Platoon on the right. Sergeant Bennie Ray was able to get two of his squads across the road that evening, but he withdrew them upon hearing that Lieutenant John H. Strom, leader of the 3rd Platoon, had also gotten men across the road.

Early in the evening, the 1st Platoon, led by Lieutenant Walter Vaughan, was sent to clear the city block directly behind Kilianskirche, which had been bypassed by the 3rd Platoon. Sergeant Edward Borboa’s 3rd Squad went through the center of this block. As they rounded a corner, they came upon a group of seven men talking together near a pile of rubble. Thinking they were men from Company C, Borboa called to them. As they looked around, Borboa saw that they were Germans. The squad’s BAR man, Private Paul Guzlides, and Private Laurence Mills opened fire, killing them all. The platoon went on through the western half of the block, but as darkness fell, they met heavier sniper and machine gun fire, and stopped their advance for the night.

The following morning, Vaughan, from his position near Kilianskirche, sent Sergeant Carl Cornelius with five men across the street into a large building, diagonally northeast from Kilianskirche, to establish an outpost and prepare for the attack that was planned for the afternoon. With the 19 men he had left, Vaughan waited in the building directly across the street from Kilianskirche. About 2:30 pm he saw a platoon of Germans coming down the road from the north and another platoon coming along the road from the east. Their movements threatened to cut off Cornelius and his five men in the outpost across the street. Both his platoon and Strom’s platoon in Kilianskirche opened up on the two German columns.

Opening the Door to the German Heartland

The German columns withdrew, but were soon back again, this time more cautiously, hugging the building walls and using the rubble piles and doorways for protection. They squeezed off Cornelius and his five men in their corner building and drove a wedge between Kilianskirche and Vaughan’s platoon. At the same time, another German counterattack was launched on the southern end of the triangular block, and the right rear of Vaughan’s platoon was forced to withdraw, breaking contact with Company C on the right. Now completely cut off, the platoon was forced to withdraw altogether from the triangular block and form a line along the road leading southwest from Kilianskirche. There they held, driving out the Germans south of Kilianskirche.

Another German counterattack came from the north as well as from the east. Kilianskirche was pounded all afternoon by a heavy German self-propelled gun that would roll up near the church, fire, withdraw, and then return from a different direction. Strom’s platoon, in the church, fired constantly at the attackers and dropped grenades out the window to halt the infiltrating Germans. The 2nd Platoon, next to the river, had already begun to attack northward when the counterattack hit. Five men led by Sergeant Max Dow crossed the road and set up an outpost, joining in firing on the Germans advancing from the open square north of the road, diagonally across the road from Kilianskirche.

Vaughan, with three men, tried to reach Cornelius and his squad holding out across the street from the church. They got as far as the building on the apex of the triangular block, where they ran into a German patrol. After a short grenade fight, the GIs were forced to withdraw. Soon, however, the short-lived pontoon bridge was completed and the tanks and TDs crossed into the bridgehead. One tank, commanded by Corporal Vincent J. Neratka, immediately raced to the aid of Company A. As the Sherman came up the road leading toward Kilianskirche from the southwest, it was hit by a panzerfaust. The crew bailed out and ran for cover as a German machine gun began to fire down the road from the north. Another Sherman and a TD were dispatched to help Company A. Approaching up a different road, the two vehicles reached Kilianskirche safely. After several exchanges, the Germans ceased firing from behind the square, but it took three hours of steady shelling before the machine guns, firing into the intersection from the north and east, were silenced.

The way was clear for Strom’s and Ray’s platoons, which had been stymied along the river road. In short dashes, one man at a time, Strom’s platoon crossed the road and took up positions in the open square amid the rubble of the wrecked buildings. By dark, a line had been established on the far side. Ray’s platoon had it easier. The roads in their sector were clear, and they were able to advance faster, with the support of two tanks and a TD, through the sniper-infested rubble along the river. Vaughan’s platoon, to the right and rear, was still unable to secure Company A’s right flank. Armor was brought up to stabilize the situation. On the afternoon of April 8, two Shermans were thrown into the struggle for the triangular block of houses. By the end of the afternoon, the Germans had withdrawn all along the line, and the three platoons of Company A, 397th, were able to establish contact with each other.

Throughout the night, artillery and nebelwerfer rocket fire harassed the Americans. The Germans also infiltrated through tunnels to take up sniping positions to fire on the GIs from the rear. Early the following morning, Hall was back in line with his platoon. Together with the tanks, the platoon pushed eastward along the road to the south of the triangular block, concentrating fire to the north and down the road to the east, where they had been receiving heavy panzerfaust and machine-gun fire. The tank fire, together with that of Hall’s and Vaughan’s platoons, drove the Germans out of the triangular block. In the afternoon a squad from Vaughan’s platoon entered the house where Cornelius’ patrol had been surrounded. Six gas masks and a bazooka were all that was found. The most serious German resistance in Heilbronn was over.

Fighting would continue for another four days against light resistance as the GIs cleared the rest of the city. The operation effectively ended with the capture of the 1,000-year-old castle atop Tower Hill. The battle for Heilbronn had raged for nine days before the American armor and infantry closed their pincers on the city. The 100th’s losses were comparatively light, given the intensity of the battle: 60 killed, 250 wounded, and 112 missing. It was impossible to determine the number of German dead and wounded, but it was believed to be considerable. The German heartland now lay open to the onrushing Americans. The end of the war was near.

My uncle George F. Sullivan was in the 100th 397th, and he was killed on April 10, 1945 according to a military site. Do you have any record of him?

Thanks,

Kathleen Sullivan Carrick

My Grandfather Robert E. O’Brien was awarded the Bronze Star for attacking a “Fortress like Factory” advancing with a smoke grenade breaking the door down Killing all the NAZIs inside with his BAR and setting fire to the enemy stores. Do you have any information about which unit he was with. We think he said he was with E company.

https://www.marshallfoundation.org/100th-infantry/

https://www.marshallfoundation.org/100th-infantry/master-repository/

My wife’s dad was in the 399th and the sites above have a history of the division.

Have fun exploring.

Clint Brumitt