By G. Paul Garson

Battlefield communications are often a matter of life and death to individual soldiers and serve to determine not only the outcome of battles but entire wars. Lowly pigeons have played an intrinsic part in world conflicts, filling the gap when modern technology failed, but their story has literally remained, in great part, unsung.

In the millennia prior to the advent of the telegraph, radio, and telephone, the transmission of information—military, economic, and civilian—relied on horse-mounted or fleet-footed human couriers (such as Phidippides, the Greek courier who ran 26 miles from Marathon to Athens, then died while proclaiming victory over the Persians in 490 bc), but a faster method was needed.

In the 5th century bc, ancient Persia and Syria developed an advanced network of messenger pigeons for their communications. The Romans also relied on trained pigeons (including those announcing the ancient Olympics) and thus the release of white doves seen today at the modern Games.

In more recent times, beginning in 1850, the famous news agency Reuters relied on 45 birds to transmit the latest news and stock prices between Germany and Belgium, finding them more reliable than the new telegraph and faster than the railway.

After using the birds extensively during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, by 1872 Germany had established a pigeon messenger network headquartered in Berlin. Russia implemented its system in 1874, and the Italians incorporated pigeons into their military in 1878.

By 1890 Canada relied in part on pigeons for civilian communications, with the U.S. Signal Corps establishing a “loft” in Key West, Florida, around the same time. The United States also often relied on pigeons prior to the laying of the transatlantic cable. France led the way in acclimating pigeons to naval gunfire, soon employing the birds on its warships by the end of the 19th century, with the British following suit.

The Germans called their courier birds Brief Taube (literally “letter pigeon”) while the French, Italians, and Portuguese called them “Messenger Pigeons.” The Belgians called their winged servants “pigeon voyageurs,” the English preferring the term “homers” because of their uncanny ability to find their way home, often from great distances.

All such “messenger pigeons” traced their lineage to the Columba livia, commonly known as the Blue Rock Pigeon or Rock Dove, although they were the product of much selective breeding and training. They should not be confused with the native North American “passenger pigeon” that numbered 3 to 5 billion and which, 300 years after European arrival in the New World, had been hunted to extinction by the outbreak of World War I in 1914.

The use of trained birds continued in both World War I and World War II when normal lines of communication were unavailable to military forces or clandestine groups. Their importance to the war effort is evidenced by the U.S. Army Signal Corps establishment of a “pigeons service” in 1917, the motivation supplied by the General of the Armies, John “Blackjack” Pershing.

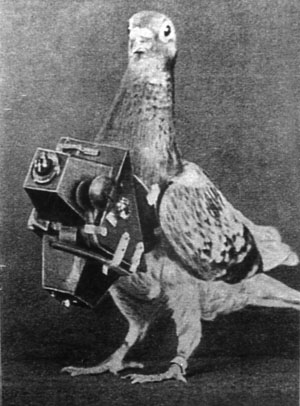

The pigeons carried small messages initially in tubes attached to their feet but larger documents were later transported via a cigar-shaped tube attached to their backs. Most often, because of the accuracy of the pigeon’s skill in finding its correct destination and the difficulty in intercepting them, the messages were not even encoded, although the birds flew as far as 200 miles and often through hostile territory, including poison gas attacks during World War I.

Due to attrition, estimates of messenger pigeon survival rates on some World War I missions were as little as 10 percent, although, all told, 100,000 were pressed into service, achieving an overall success rate of 95 percent. They were also carried on ships so that in the event of a sinking by enemy submarines, the pigeons could be released to carry the location of the sinking to rescuers.

A bird called Cher Ami (“Dear Friend”) delivered a dozen vital messages at Verdun and was thus awarded the famous French Croix de Guerre. Later she delivered a message that saved the lives of many soldiers in the “Lost Battalion” of the U.S. 77th Division. Though shot in the chest and having lost most of one leg, the bird delivered its message (“We are along the road parallel to 276.4. Our own artillery is dropping a barrage directly on us. For heaven’s sake, stop it.”). After she died in 1919, her body was stuffed and mounted, sent to the United States, and put on display at the Smithsonian Institution.

Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, and its forces reaching the Ukrainian city of Kiev, SS police authorities, using the rationale of communication with the enemy, rounded up all the area’s several hundred pigeon keepers and had them executed along with their birds.

Shortly after U.S. entry into World War II, new recruits were culled for pigeon experts, while civilian pigeon fanciers were asked to either sell or “volunteer” their birds. When a general call went out on January 9, 1942, it resulted in enthusiastic support, one shipment from New York City consisting of some 52,000 birds.

Joining the war effort was the American Racing Pigeon Union and the International Federation of American Homing Pigeon Fanciers. Many prize-winning and very valuable racing birds were turned over to the U.S. Signal Corps.

The department was eventually manned by 150 officers and 3,000 enlisted personnel, many of them pigeon experts in civilian life. The soldiers responsible for their care and training were dubbed “pigeoneers.” Credited with bringing the American messenger pigeon up to modern military speed was Colonel Clifford A. Poutre, Chief Pigeoneer of the U.S. Army Signal Corps Pigeon Service (1936-1943). Colonel Poutre rejected the pattern of training by starvation used in World War I to one focused on kindness. His pigeons responded with significant improvements in speed, accuracy, and performance.

Pigeon breeding and training bases were set up in Georgia, Missouri, New Jersey, and Texas. The search was on for the fastest birds for the job at hand, the new crop of birds doubling the World War I distance, often traveling 400, sometimes 600, miles to accomplish their mission, and at times reaching 60 mph in short sprints. While some 50,000 birds were employed in military service during World War II, half that of World War I because of advances in electronic communication, they still played a significant role.

In the late 1930s, prior to World War II, Lieutenant Claire Lee Chennault (of “Flying Tigers” fame) brought with him to China several hundred messenger pigeons along with his group of intrepid volunteer American flyers and planes in aid of China’s battle against the Japanese. At war’s end he would leave them behind, the birds remanded into the Chinese military and the foundation for that country’s still active military messenger pigeon program.

Additionally, many a British Royal Air Force crewman owed his life to a pigeon as one in every seven who had crashed landed or parachuted into the sea was rescued, thanks to a message delivered by one of the birds, which were often carried as standard passengers on English bombers.

The U.S. Army Air Forces followed suit on some missions. It was soon learned that the birds could withstand temperatures of -35 degrees and could be dropped from a plane at 375 mph without injury. In addition, a special pigeon-carrying sling was adopted by airborne troops that, once on the ground, converted into a backpack.

Moreover, thousands of specially constructed carriers were parachuted into France during the Normandy D-Day invasion with instructions requesting that their French finders send back intelligence about German defenses.

In The Longest Day, author Cornelius Ryan noted, “Correspondents on Juno [Beach] had no communications until Ronald Clark of United Press came ashore with two baskets of carrier pigeons. The correspondents quickly wrote brief stories, placed them in the plastic capsules attached to the pigeons’ legs, and released the birds.

“Unfortunately, the pigeons were so overloaded that most of them fell back to earth. Some, however, circled overhead for a few moments—and then headed toward the German lines. Charles Lynch of Reuters stood on the beach, waved his fist at the pigeons, and roared ‘Traitors! Damned traitors!’” (This scene was included in the 1962 Hollywood version of the book.)

Said Ryan, “Four pigeons proved loyal. They actually got to the Ministry of Information within a few hours.”

An American pigeon was cited for bravery during World War II when its message was delivered at great speed, thus averting an Allied bombing of 1,000 British troops who had just occupied an Italian town scheduled for attack just five minutes after the bird’s timely and preemptive arrival.

The bird personally received from the Lord Mayor of London the Dickin Medal for Gallantry, Britain’s highest animal award. By the end of the war, some 30,000 messages had been transmitted by pigeon, with an estimated 96 percent success rate.

The English effort to utilize messenger pigeons during both world wars is credited to efforts of the British Pigeoneers, Lt. Col. A.H. Osman and Mr. J.W. Logan, Esq. During the war a very sizable fine of 100 pounds Sterling and a six-month prison term awaited any person found in the United Kingdom to have harmed a carrier pigeon.

Both the British and French governments recognized the pigeons’ contributions through the bestowing of medals, and many were heralded in the public press as “heroes.”

The means by which the messenger pigeon travels its course so accurately is attributed to a variety of reasons: that it sees both in color and ultra violet, that it can “read” landmarks such as roadways and intersections, and also that it responds to the electromagnetic field of the earth.

One factor that seems to determine their speed when returning to the home loft is jealousy. The males who mate for life seem to fly faster when they notice a new male has been added to their nesting loft just prior to their departure.

Despite the impression left by their bobbing heads, the motion required to gauge their earthbound position while walking due to their lack of stereoscopic vision, pigeons are quite bright. They are one of only six species, and the only nonmammal, with the ability to recognize itself in a mirror. Tests have also shown that pigeons can distinguish the 26 letters of the English alphabet.

Famous American behavioral scientist B.F. Skinner, known for his work in behavioral conditioning, was contacted during the war by the U.S. Navy seeking a new weapon against the German Navy’s Bismarck-class battleships; thus was born Project Pigeon.

It turned out that one of Skinner’s favorite research animals was the pigeon, and thus the idea was born to produce a very small missile divided into three sections, a pigeon encased in each. Projected on a tiny screen was a view of whatever was in front of the missile, the pigeons trained to peck toward the image and thereby working as the guidance system. Skinner was convinced a pigeon-guided missile would work, but apparently no one took him seriously and the plan was scrapped.

The deliberate targeting of messenger pigeons by all combatants was seen as a legitimate means of disrupting enemy communications. Pigeons were machine gunned out of the sky in World War I or fired upon from the trenches by individual soldiers taking potshots.

During World War II, both German and Japanese troops fired on the birds with specially supplied shotguns while natural predators, such as hawks, also took their toll, as did an unlucky intersection with bursts of flak directed at other airborne targets. Both the Germans and British released their own hunting falcons which, however, they found could not distinguish between enemy and friendly pigeons.

Birds occasionally became disoriented, injured, or captured as “POWs.” One World War II report states that a homing pigeon released by its American handlers ended up in German hands during the winter 1944 campaign in Italy. It eventually reappeared at its American loft with its message capsule intact but, once opened, the note read: “To the American Troops: Herewith we return a pigeon to you. We have enough to eat. —The German Troops.”

When the U.S. military disbanded its messenger pigeon operations in 1957, Colonel Poutre, then 103, was honored for his contributions by his release of the last of the country’s military homing pigeons.

Food shortages during and after World War II’s end brought about the disappearance of untold numbers of pigeons from the streets and plazas of Europe; however, their numbers have long since recovered and flourished.

Moreover; the interest in homing and racing pigeons has also skyrocketed. In early 2011 during an auction in Kermt, Belgium, a rare Belgian racing pigeon brought a record-breaking bid of 156,000 Euros ($208,000), the bird going to China, where the sport has become a phenomenon with some 30,000,000 registered racing pigeons.

In late 2010 China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) initiated a program to train 10,000 pigeons for a “reserve pigeon army” that would provide back-up in case its high-tech electronic communications systems were put out of action. While history seems to be repeating itself, some wags would warn that the United States is now facing a “Messenger Pigeon Gap.”

So much information! My Father Robert Leslie Homrig was in the 280th Signal Pigeon Corp with Patton’s Army in 1944 to 1945 in France, Belgium, they did change the numbers of the Signal Pigeon Corp!

Would love to know about his unit!

BD 7/10/1922 passed away 4/20/2009 in San Francisco, CA