When the Civil War broke out in 1861, the great American poet Walt Whitman was a man on the skids, personally and professionally. His revolutionary book of poems, Leaves of Grass, had been largely overlooked, and Whitman was spending most of his time drinking with his fellow bohemians at Pfaff’s beer cellar in New York City.

Things changed dramatically in December 1862, after Whitman’s younger brother George was wounded while fighting in the Union Army at Fredericksburg, Virginia. Rushing to Washington, Walt spent days searching frantically for George in the overcrowded army hospitals in the nation’s capital. As it turned out, George was not badly wounded—he had merely been cut on the cheek by a Rebel shell fragment and was already back with his regiment, the 51st New York, by the time Walt discovered what had happened.

The experience changed Whitman overnight. The sights and sounds of the hospitals stayed with him, and the poet returned to New York City only long enough to gather his possessions and return to Washington. He was now a man with a mission.

For the next two years, Whitman functioned as a sort of one-man Sanitary Commission, visiting the various hospitals and doing whatever he could to spread a little cheer to the patients confined there. His meager earnings as a government clerk went toward buying the soldiers’ humble but much appreciated gifts: fruit, ice cream, candy, cookies, pickles, brandy, wine, tobacco, books, stamps—anything that might make their stay in the hospital a little easier.

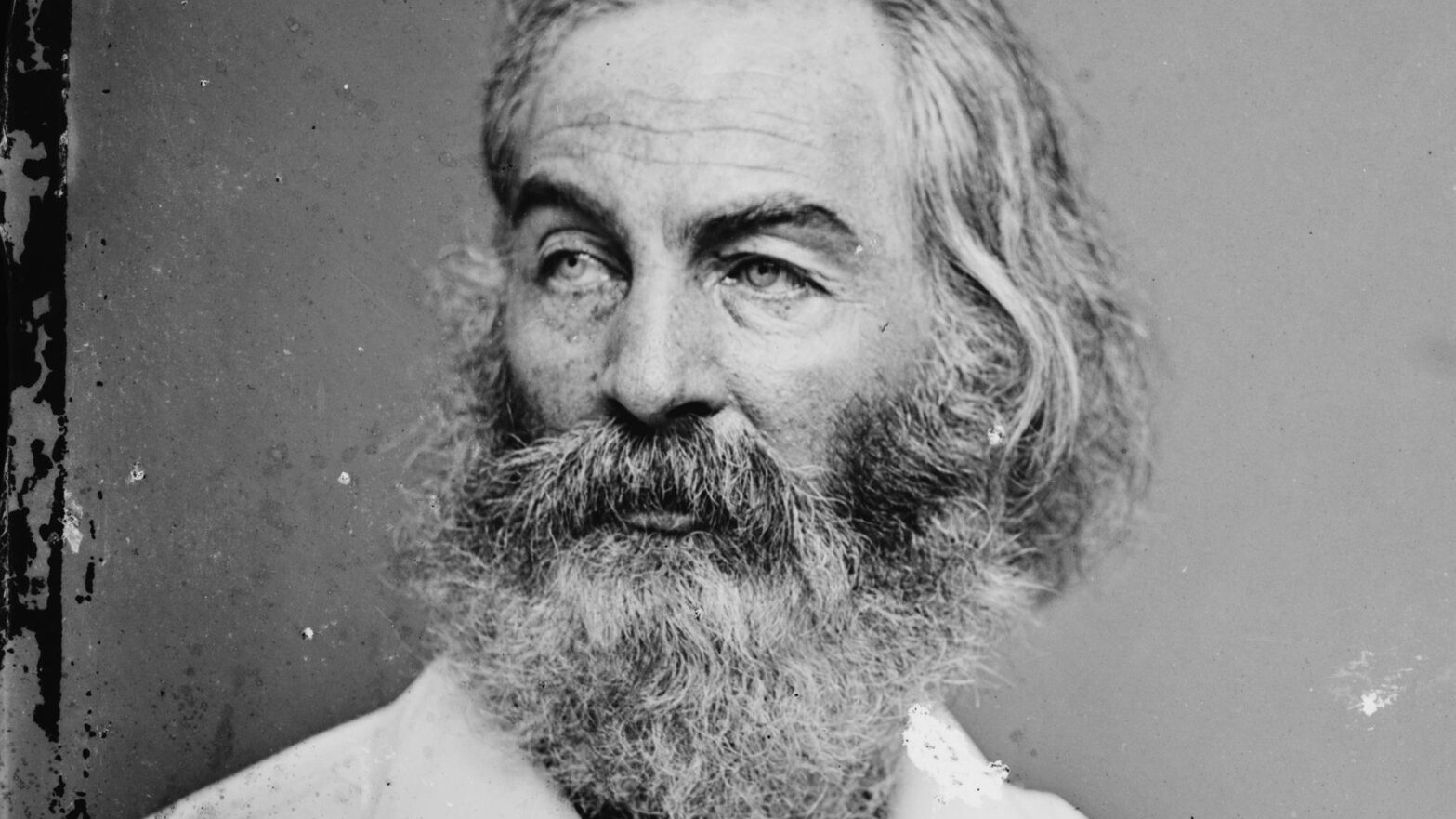

Mostly, Whitman gave of himself. “In my visits to the hospitals,” he recalled, “I found it was in the simple matter of personal presence, and emanating ordinary cheer and magnetism, that I succeeded and helped more than by medical nursing or delicacies, or gifts of money, or anything else.” Over the course of the next three years, he personally visited tens of thousands of soldiers. His long white beard, plum-colored suit, and bulging bag of presents gave him a decided resemblance to Santa Claus, and the patients called after him at the end of each visit: “Walt, Walt, come again!”

Not everyone approved of Whitman’s assistance, particularly the members of the more formally run U.S. Sanitary Commission. One commission member, Harriet Hawley, the wife of a Union colonel, was outspoken in her disapproval. “There comes that odious Walt Whitman,” she wrote to her husband, “to talk evil and unbelief to my boys. I think I would rather see the Evil One himself—at least if he had horns and hooves. I shall get him out as soon as possible.”

Whitman, for his part, returned Mrs. Hawley’s dislike. He complained to his mother that Sanitary Commission members were mere “hirelings” who “get well paid & are always incompetent and disagreeable.” That was uncharacteristically harsh for the ordinarily sunny and good-natured poet. But the unending stream of human devastation eventually wore him down, and Whitman began suffering from headaches, insomnia, dizziness, and depression. “I have seen all the horrors of soldier’s life,” he wrote. “It is awful to see so much, & not be able to relieve it.”

The soldiers themselves begged to disagree that he had not done nothing to relieve their suffering, if only for a little while. One of them, 20-year-old Lewy Brown of Elkton, Maryland, who lost a leg at Rappahannock Station, spoke for many when he wrote to Whitman after the war: “There is many a soldier now that never thinks of you but with emotions of the greatest gratitude. I never think of you but it makes my heart glad to think I have been permitted to know one so good.”

Whitman remained humble about his hospital service. “I only gave myself,” he said simply. “I got the boys.” But in more ways than one, as Lewy Brown said, Whitman had truly lived up to his nickname: “the Good Gray Poet.”

Roy Morris Jr.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments