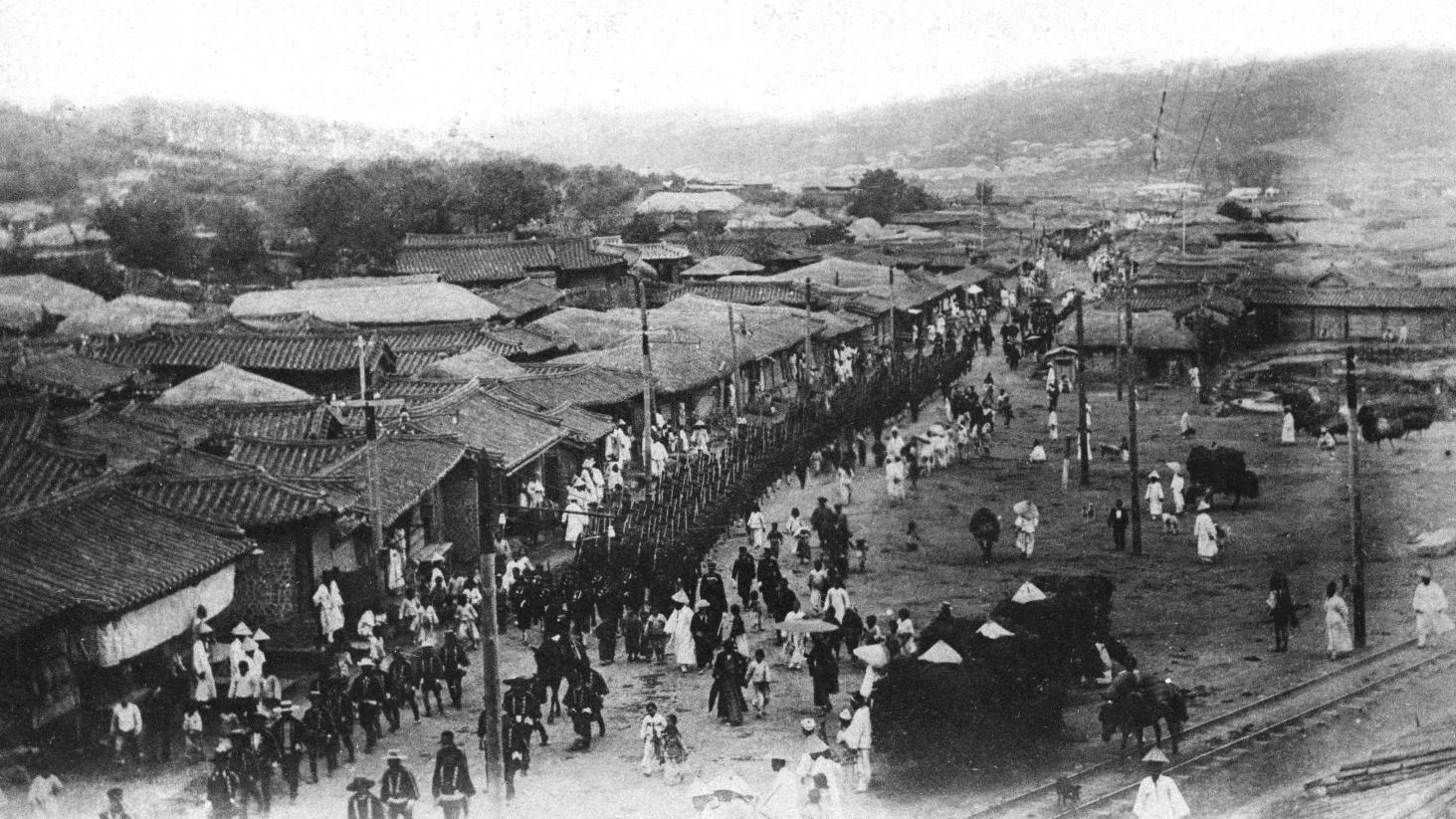

For centuries the Japanese and Korean peoples have remained wary of one another, warring and occupying, threatening and maintaining an uneasy peace at various times. Early in the 20th century, following the comments made by one Japanese diplomat that the Korean peninsula was a dagger pointed at the throat of Japan, the defeat of Imperial Russia during the controversial Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, and the burgeoning expansionist sentiment within the Japanese government, Japan formally annexed Korea and initiated 35 years of harsh rule.

From 1910 until the end of World War II in 1945, Japan exploited Korea for its own purposes, conducting horrendous biological and chemical warfare experiments on Korean prisoners and impressing Korean laborers into construction projects to build fortifications on the islands of the Pacific that were later stormed at tremendous costs by American forces during World War II. Most noticeably today, a strong resentment lingers among the Korean people for the Japanese practice of forcing Korean women into sexual slavery during the war as “comfort women” subservient to Japanese soldiers away from the home islands.

During the last quarter century, documentation of widespread atrocities committed by the Japanese in Korea has come to light and exacerbated the distrust and bitterness of the Korean people against their former colonial rulers. While significant ill will remains and some survivors of the occupation era continue to seek justice, South Korea and Japan have yet to settle the issues of compensation for “comfort women” or their surviving family members as well as the actual ownership of a group of small islands lying off the coastlines of the two nations.

Nevertheless, in something of a surprise last June, the governments of Japan and South Korea abruptly announced their intent to sign an agreement to share intelligence information. In itself, the intelligence agreement is a pragmatic move that would enhance the security of both nations in an unstable region. Regardless, the day after the announcement, the two governments were compelled to postpone the signing ceremony due to an outcry of disapproval from thousands of South Korean citizens.

An opposition leader scored the government of South Korean President Lee Myung-bak, asserting that the administration has become more pro-Japanese in recent months than pro-American while the United States maintains a standing presence of more than 30,000 troops in South Korea. These troops and their South Korean allies patrol a restless border along the 38th parallel between the North and South that has been maintained since the agreement that ended the shooting in the Korean War in 1953.

The proposed intelligence-sharing agreement would represent the first military pact between the two countries since the end of World War II, and the reasons for it are obvious. The continuing threat from North Korea imperils the security of both nations. The unprovoked communist shelling of a South Korean village and the sinking of a South Korean naval vessel apparently by a North Korean submarine last year combined with North Korean efforts to develop an operational nuclear missile capable of striking cities as distant as the United States loom large, particularly with the change in leadership following the death of Kim Jong-il and the rise of his son Kim Jong-un to power in the repressive communist country. Further, both Japan and South Korea remain concerned with the conduct of North Korea’s closest supporter, China.

The agreement would provide for the sharing of data and intelligence information on missile defenses and development, the North Korean nuclear program, and the activities of the Chinese military, particularly deployments and exercises. Both North Korea and China maintain mammoth military forces.

For what it is worth, when the agreement was made public the North Korean government accused the Lee administration of “selling the nation out.”

The Japanese foreign ministry hailed the pact as a “historic event,” but agreed to postpone the formal signing of documents at the request of the Seoul government.

Modern geopolitical cooperation is imperative among nations; however, old wounds that may never heal continue to impede progress.

Michael E. Haskew

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments