By Ron Gilliam

A hard, late-afternoon rain was falling on May 5, 1862, and the slopes at the foot of Puebla, Mexico’s twin forts were too slippery for another assault. In muddy ditches in front of the outlying earthen breastworks lay hundreds of dead and wounded French soldiers, their blue tunics and red-and-white pantaloons stained with blood. Exhausted and dazed by three bloody and fruitless assaults, the 4,000 sodden, smoke-begrimed survivors had regrouped in a defensive position just out of range of the forts’ well-served guns, waiting for a Mexican counterattack that never came. When night fell, the weary troops slogged away to a chilly bivouac. They could still hear the Mexicans celebrating their victory, cheering and singing the “Marseillaise,” the anthem of liberal revolutionaries everywhere, but ironically banned in France by Emperor Napoleon III.

This was not the way it was supposed to be. Veteran troops led by generals who had fought under the first Napoleon in the Corsican general’s wars of conquest, France’s army in 1862 was universally regarded as the world’s best. It should have made short work of any Mexican force. As he set out for Mexico City, the French commander, Comte de Lorencez, had smugly written to his minister of war in Paris, “We have over the Mexicans such a superiority of race, organization, discipline, morality, and elevated spirits that I beg you to inform the emperor that, from this moment on and at the head of six thousand soldiers, I am the master of Mexico.”

Napoleon III’s Grand Design for Latin America

France’s intervention in Mexico was the first phase in Louis Napoleon’s “Grand Design,” a scheme that had been conceived during Louis’s long exile in England and the United States. Napoleon III’s design envisioned Paris as the political hub (with Rome the religious hub) of a cultural, commercial, and religious empire uniting all the Catholic nations of Europe. Latin America, a term Napoleon III coined, was a critical part of his so-called Latin League. With a new canal in Mexico or Central America to complement the Suez Canal already being built with French investment, the League would dominate world trade.

Louis began to further his Grand Design after returning to France during the revolutionary turmoil of 1848. Using nostalgia for France’s Napoleonic greatness to win election as president, he seized absolute power following a political crisis in 1851 and converted his presidency into a monarchy in 1852, proclaiming himself Emperor Napoleon III. Convinced that democratic republicanism was a pernicious system of government, he resolved to replace Latin America’s failed republics with “enlightened” monarchies that presumably would provide the stability and social discipline needed for national progress. The plan’s chief impediment was the prodigious development of the fundamentally Anglo-Saxon, Protestant United States, which advocated democratic republicanism and repudiated in its Monroe Doctrine any European interference in the Americas. Imperial France would “create a counterweight” to American influence, Napoleon III envisioned, and Mexico would become the Crimea of the New World, blocking American expansion southward as allied occupation of the Crimean peninsula had blocked the southward expansion of the Russian Empire seven years earlier.

The Empress Eugénie, Louis’ politically reactionary and vengeful Spanish wife, was the chief sponsor at the French court of a clique of ex-colonial émigrés and recently exiled Mexican Conservatives, and a full participant in her husband’s Grand Design. After acquiring independence, Mexico had endured a brief, unhappy experience with monarchy before establishing a constitutional government modeled on that of the United States. But as democracy failed to take root, an “enlightened monarchy” for Mexico increasingly attracted self-styled Conservatives. In September 1861, Mexican exiles asked Eugénie to persuade the emperor to lend France’s diplomatic and military support to establishing a European prince on the imperial throne of Mexico. Realizing immediately that such a dependent prince could be a useful instrument in achieving his Grand Design, Napoleon III readily agreed.

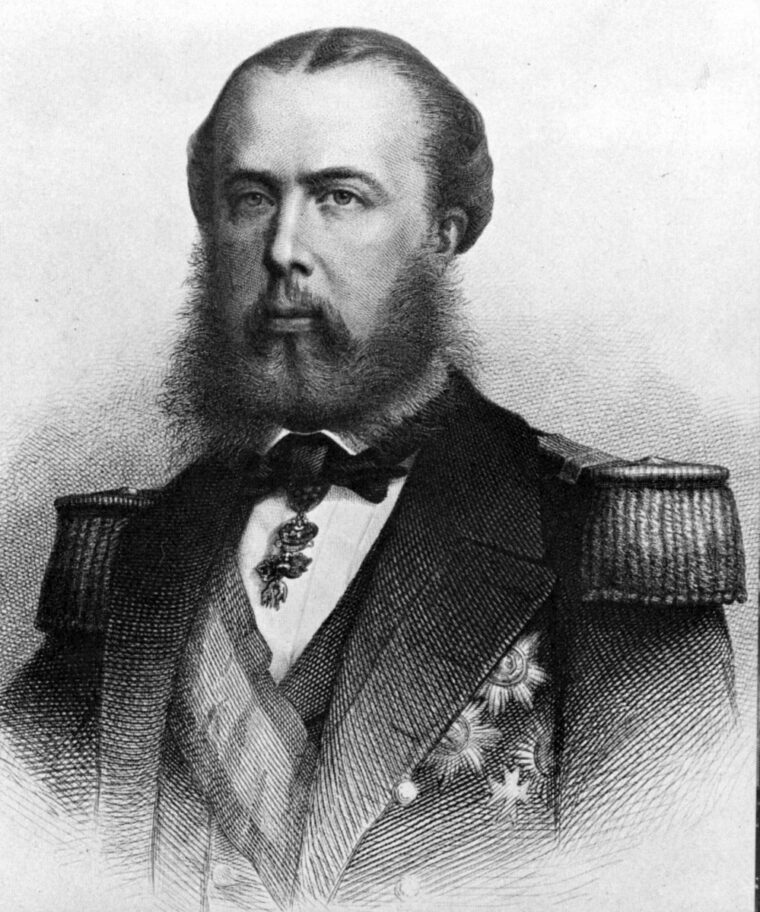

France Chooses a Puppet Prince

After considering various available candidates, Louis and Eugénie selected Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian of Habsburg, the younger brother of Austrian emperor Franz Josef. “Ferdinand Max” was a dreamy-eyed, foppish young man of no particular attainments other than appointment by his brother as admiral of Austria’s Adriatic fleet and governor of her dwindling Italian territories. Like Louis Napoleon, Maximilian harbored no doubts that monarchy was the best as well as the most natural form of government and that he was destined by heritage and divine law to occupy such a throne. In October, a delegation of Mexican exiles offered him the crown of Mexico and assured him that the Mexican people would receive him gladly as their sovereign.

Before Maximilian could actually assume his new crown, a large military expedition would have to defeat Liberal President Benito Juárez’s republican forces and pacify a country well known for its guerrilla warfare and banditry. Providentially, Juárez had just handed Napoleon III the perfect cover for a military expedition. After 40 years of revolving military dictators floating loans in Europe instead of collecting taxes from large landowners and the Catholic Church (which still owned half the productive land in the country), Mexico had created an unmanageable foreign debt. On July 17 the Mexican congress, facing bankruptcy after three years of civil war, had passed a resolution suspending interest payments to foreign creditors for another two years. The foreign creditors complained to their governments, most loudly Louis’ half-brother, the Duc de Morny, a heavy investor in bonds issued by the Conservative government before its defeat in 1860. Even though Juárez had warned that such bonds were invalid, Morny and his Swiss co-investors demanded that Napoleon III force the irresponsible Mexicans to honor the bonds and resume interest payments, and to punish them for their previous delinquencies.

France, Spain, Great Britain Join Forces to Collect Mexico’s Debts

Napoleon III knew that to avoid conflicts with other major creditor nations such as Great Britain and Spain, his military expedition would have to be a tripartite undertaking. As a willing partner, Great Britain could hardly condemn France for intervening in Mexican affairs, and together they could keep Spain from acting alone to reconquer its former colony and install a Spanish prince. Napoleon III proposed that the two countries occupy Veracruz, Mexico’s principal seaport, and seize the customs house, applying the incoming duties to repayment of their countries’ creditors. A joint operation also provided cover for Louis’ imperial scheme. Choosing the right moment, Napoleon III’s foreign minister suggested to the British that a “conference of Mexican notables” might be convened to choose a foreign prince as their ruler, saying that a Mexico “regenerated” by an enlightened monarchy and pacified with a stable government, “would form an impassable barrier to the encroachments of North America and would provide an important opening for English, Spanish, and French trade.” With regard to the United States, the timing was impeccable: although sympathetic to the Juárez government, America’s involvement in her own Civil War made any inconvenient interference virtually impossible.

In October 1861, representatives of France, Spain, and Britain met in London and formally agreed to send naval forces and 10,000 troops to Veracruz. Spain would furnish 7,000 men under General Juan Prim, Conde de Reus y Marquis de los Castillejos, and France would send 2,500 troops under Vice Admiral Jean Jurien de la Gravière. Great Britain, Mexico’s biggest creditor, agreed only to land 700 marines under Commodore Hugh Dunlop. The first 6,000 Spanish troops, dispatched from Cuba, arrived at Veracruz on December 8, while the French and British squadrons were still in the mid-Atlantic. Raising the Spanish flag over the ancient fortress of San Juan de Ulúa, where a Spanish garrison had held out for years after Mexico’s de facto independence, they issued a self-serving proclamation that Spain had “no mission of conquest but was solely demanding satisfaction for the non-fulfillment of treaties.” Juárez, who had already transferred all customs funds to Mexico City and closed the port to international commerce, ordered the Veracruz state governor not to resist the Spanish landing.

The Short-Lived Tripartite Alliance

After the first French and British contingents arrived early in January 1862, the Tripartite Alliance’s representatives formed a commission to negotiate with the Mexican government. The commissioners were the three military commanders and the British and French ambassadors to Mexico: Sir Charles Lennox Wyke and Pierre Alphonse Dubois, Count de Saligny, formerly the French chargé d’affairs to the Republic of Texas 25 years earlier. General Prim, who was also a senator, handled both diplomatic and military functions for Spain and served as commission chairman. The commission almost immediately became dysfunctional. Great Britain and Spain agreed to negotiate on Juárez’s American-backed debt repayment plan, but Saligny insisted on an ultimatum, his unwillingness to compromise raising suspicions of secret instructions to force a confrontation. Saligny promoted the idea of a monarchy, but Prim and Wyke both declined to support it, Wyke declaring that he had discovered no sympathy for such a monarchy during his many years in Mexico. Prim, whose Mexican uncle by marriage was a member of the Juárez cabinet, was similarly disinclined to support the French plan.

On February 19, Prim met with Mexican Foreign Minister Manuel Doblado at La Soledad, 25 miles west of Veracruz, and assured him that rumors of the allies’ intentions of upsetting the present government and establishing a monarchy in its stead were “entirely false.” With the dreaded yellow fever season coming on, Doblado suggested that the Alliance move its unacclimated troops from the tierra caliente (hot country) of the tropical coast to cooler, healthier upland locations. The Mexicans would not oppose such a movement, Doblado said, provided the allies recognized the Juárez government and agreed to negotiate their claims. It was agreed that the allied forces would not attempt to pass fortified positions garrisoned by the Mexican army, and that in the unfortunate case that negotiations were broken off, the allies would abandon their new positions and return to Veracruz.

As 29 French soldiers had already died and 159 more were in the hospital with tropical diseases, all the commissioners were happy to agree except Saligny, and he was overruled. The allied troops set off for the uplands, the French to Tehuacán and the Spanish to Córdoba. Watching the long, hot, straggling columns, Admiral Jurien was glad the agreement had relieved them of any threat of Mexican attack. The British marines were to have gone to Orizaba, 10 miles west of Córdoba, but Commodore Dunlop ordered them back aboard ship, as the British Foreign Office, having belatedly surmised French intentions, had instructed him not to proceed beyond Veracruz.

On March 6, while the allied troops were on the march, the man Napoleon III had chosen to command the military expedition in Mexico debarked at Veracruz. Self-confident to the point of arrogance, Brig. Gen. Charles Ferdinand Latrille, Comte de Lorencez, had learned his craft under the first Napoleon. Lorencez was well-connected politically, having married the daughter of a marshal of France. Lorencez brought with him 4,711 more troops and 643 cavalry in an 11-ship convoy that arrived in Mexico between March 5 and April 17. Leaving behind 900 soldiers and marines to secure his Veracruz base and line of communication, Lorencez hurried on to join Jurien at Tehuacán.

Lorencez also brought with him the Mexican Conservative exile General Juan Nepomuceno Almonte, sent by Napoleon III to rally Mexican support for the French. The illegitimate son of the priest José Morelos, one of Mexico’s three great liberators in the 1810-1822 Independence struggle, Almonte had been educated in the United States and served as Santa Anna’s aide-de-camp at the Battle of San Jacinto, where Texas won her independence in 1836. As Mexico’s minister to the United States 10 years later, he helped precipitate the Mexican War by severing diplomatic relations when the United States annexed Texas. After the Liberals triumphed in the War of the Reform, Almonte stayed on in Paris, meeting secretly with Napoleon III to plot the overthrow of the Mexican republic and installation of Maximilian as emperor. Referring to himself (to Lorencez’s annoyance) as “the supreme power of Mexico,” Almonte expected to head a pro-monarchist interim government, and perhaps a Conservative republic in case the monarchy scheme failed.

Almonte’s presence and the size of the French reinforcement removed all British doubts of a hidden French agenda. Queen Victoria wrote to her foreign minister: “The conduct of the French is everywhere disgraceful. Let us only have nothing to do with them in future.” On March 20, the French foreign minister sent Napoleon III’s new instructions to Jurien and Saligny, repudiating the Convention of La Soledad and endorsing Saligny’s impossible January 12 ultimatum. If Juárez rejected it, the French were to advance on Mexico City at once. Shown these instructions in Paris, the Mexican minister asked for his passport, saying in protest, “Mexico may be conquered, but will never submit, and will not be conquered without having given proof of the courage and virtues which are not credited to her.”

Disgusted, Prim wrote the French foreign minister contradicting Saligny’s claim that the French would be welcomed as liberators: “They hate us here. The foreigner in arms is always odious.” Separately, he warned Napoleon III that while they could seat Maximilian on a throne in Mexico City, the only people who would accept him would be Conservative leaders eager for French military support against the Liberals. On April 9, the British and Spanish high commissioners formally withdrew from the Tripartite Alliance and ordered their forces to retire to Veracruz and re-embark for home. The French would have to proceed alone.

Napoleon III’s instructions recalled Admiral Jurien to Paris, leaving Lorencez in sole command of the French expeditionary force, which now numbered 7,200 men and 850 cavalry. Another 30,000 troops were coming, but Lorencez saw no need to wait for reinforcements. Leaving 340 men in the hospital in Orizaba, Lorencez set off with 6,000 troops, reluctantly honoring the treaty obligation to back-track to Veracruz before marching on Mexico City. However, in Córdoba, the new French commander seized on a misunderstanding over the status of the French sick in Orizaba as a pretext for breaking the Treaty of Soledad, and ordered his scattered columns to concentrate there.

Disaster Strikes the Mexican Forces

While hoping for a diplomatic agreement at La Soledad, Juárez had taken the precaution of ordering regional army units to reinforce the Army of the East to block any French advance. On March 6, while Lorencez was debarking at Veracruz, the First Brigade of Oaxaca, one of the army’s most experienced units, arrived at the army’s headquarters at San Andrés Chalchicomula, 25 miles west of Orizaba. As customary, the troops were accompanied by their women, the self-styled soldaderas who cooked and cleaned for them and nursed the sick and wounded. As the first and second battalions camped around a large barn, food vendors gathered and the soldaderas prepared tortillas and started cook fires, unaware that 4.4 tons of gunpowder was stored in the barn. Without warning, there was a tremendous explosion. When the smoke and dust had cleared, blood and body parts covered the campground. Some 1,042 Oaxacan Indian soldiers had been killed and another 200 injured; 475 soldaderas and 30 vendors had also perished, and 500 villagers had been injured. At one calamitous blow, Juárez’s army had lost two of its best infantry battalions and most of its ammunition reserve.

News of the disaster reached Jurien as his troops were arriving at Tehuacán, 40 miles away. Astutely sensing an opportunity to demonstrate that the French had come to rescue, not oppress, the Mexican people, he dispatched army medical teams to help the injured, and their skill undoubtedly saved many lives. The goodwill gesture would prove short-lived.

Zaragoza’s Daunting Task

With the French concentrating at Orizaba and the Army of the East in disarray, Juárez decided to put his best and most trustworthy general in charge at the critical post. Usually favoring spectacles and a black civilian suit, Brig. Gen. Ignacio Zaragoza looked more like a young professor than a Mexican general. Nevertheless, he had been born into the army, though not into one of the criollo (Mexico-born Spanish) military families whose idle offspring swelled the officer corps. His father had been a sergeant in the garrison at Presidio La Bahía del Espíritu Santo; his mother was a San Antonio native. Growing up in the north, Zaragoza experienced foreign invasion early. Texan independence in 1836 meant relocation to Matamoros for the Zaragoza family. After studying for the priesthood, 17-year-old Ignacio fought against General Zachary Taylor’s invasion force as a private in the Guardía Nacional.

Five years after the Mexican War, Zaragoza decided that he had a military calling. Returning to the army to fight for the Federalist cause, he was spotted as a rising star and promoted rapidly to captain. His instrumental role in defeating Santa Anna’s Centralist supporters in the decisive Battle of Saltillo won him field promotion to colonel. During the War of the Reform, he was promoted to brigadier general for his part in the Liberals’ victories at Zacatecas and San Luis Potosí. By 1860, when the Conservative forces were decisively defeated and the three-year war formally ended, Zaragoza had defeated in battle every leading Conservative general. In 1861, Juárez named him secretary of war and navy.

Zaragoza faced a daunting task. Lorencez’s decision had cost him three weeks’ time and forced him to make his first stand at the pass through the Cumbres de Acultzingo, between Orizaba and the high central plateau of the tierra fría (cold country), close to Puebla and Mexico City. On April 27, Zaragoza rushed 4,000 men and several guns to the village of Acultzingo, where the National Highway passed between 8,000 and 10,000-foot peaks, their lower slopes covered in lush upland jungle and coffee plantations. Early the following afternoon, a company of French Zouaves came over the summit in a skirmish line and the Mexicans opened fire. In a sharp three-hour fight, with a loss of two killed and 36 wounded, the French forced the Mexicans from the pass. Lorencez reveled in the triumph—this was just the sort of easy victory he was expecting. His troops reached Palmar, 20 miles west, on May 1, but the Mexicans already had pulled out.

Puebla Prepares for the French Attack

On May 3, Zaragoza reached Puebla and set feverishly to work. The city’s famous forts showed decades of neglect. On the north, the stone forts of Loreto and Guadalupe stood astride the National Highway, 1,000 yards apart atop a low rise. Forts San Javier and Santa Anita, on the western side, and Fort del Carmen, on the south, were smaller and less solidly built. Zaragoza put General Joaquín Colombres of the Engineer Corps in charge of fortifying Puebla. He had less than 48 hours. With little rest, troops who had fought at Cumbres de Acultzingo and marched 65 miles to Puebla threw themselves into repairing fortifications, digging trenches, and erecting breastworks. The following day, the French arrived at the village of Amozoc, eight miles northeast of Puebla. Saligny and the Mexican Conservatives had assured Lorencez that Puebla, with its clerical influence and monarchist bishop, was a staunchly conservative city whose 80,000 inhabitants would shower the French with flowers. The road to Mexico City seemed wide open.

Much of Puebla’s population did indeed favor the Conservatives, but many Poblanos were also willing to fight for the Reform—or at least to resist a foreign invasion. “The populace en masse has presented itself to request arms,” the city’s Liberal newspaper rhapsodized. “A multitude of separate companies and pickets has formed almost instantaneously.” City block wardens tallied available able-bodied men, serviceable firearms, and edged weapons. New militiamen were led through tactical drills in the Plaza of San José, 800 yards south of Fort Loreto; most had to be shown how to load a musket. In a corner of the square, a field hospital was set up, and matrons and young ladies from some of the city’s first families mixed with humble soldaderas, all offering their services in the bloody fight to come.

Zaragoza learned that his old enemy, Conservative General Leonardo Márquez, was at Izúcar de Matamoros, 45 miles to the south, heading north with some 2,500 mounted guerrillas to join Lorencez. Zaragoza immediately dispatched a 2,000-man cavalry brigade to head them off. That night Zaragoza’s last troops arrived; no other support would be available before the battle. Calling together his generals and field officers, he frankly explained the situation they faced. Then, sensing an undercurrent of defeatism, he declared, “It will not be said before the whole world that a force of six thousand men has dominated a country of eight million inhabitants without meeting the least resistance; it is necessary to fight.”

At Amozoc, Lorencez learned that Zaragoza was at Puebla preparing to defend the town. The Conservative generals advised bypassing the city and continuing straight to Mexico City. The French commander responded that he had to take Puebla because a bypassed enemy could cut his line of communication and attack his rear. In that case, they urged, attack Puebla from the south or east, avoiding the northern fortifications. Almonte, who knew Puebla well, having captured and defended it during the War of the Reform, claimed the city had never been taken from the north and advised marching around it to attack from the west. But a Mexican engineer officer assured Lorencez that the fortifications on Loreto and Guadalupe hills were not as strong as they looked—the breastworks were not embanked and the redoubts would not withstand heavy bombardment. Furthermore, the Juarista army, aware of this, was too demoralized to worry about. That was just what Lorencez was hoping to hear—a glorious victory required storming the forts. He dismissed the meeting with a nonchalant air. “Until tomorrow, gentlemen,” he said. “We shall see each other in Guadalupe.”

Zaragoza assembled his men on the plaza. Most of them were recently recruited and untried in battle. Foregoing the usual “victory or death” speech, he told them simply: “Our enemies may be the world’s best soldiers, but you are the best sons of Mexico, and they want to seize our country from you. Today, you are going to fight for a sacred objective; you are going to fight for the fatherland and I promise that this day we shall triumph in a day of eternal renown. I see victory in your faces. Let us have faith! ¡Viva la independencia nacional! ¡Viva México!” The soldiers enthusiastically echoed the call.

Zaragoza’s Battle Plan

Much of the Army of the East was already engaged against Conservative guerrillas threatening the Liberals’ control of parts of the country after the War of the Reform. To defend Puebla, Zaragoza had only the 12 battalions of the 2nd Infantry Division, four and a half independent infantry battalions, and a cavalry regiment, some 5,450 men in all. Though close in numbers to Lorencez’s 5,730 troops, most of Zaragoza’s men were far inferior in training, equipment, and experience. The French veterans of Italy, Morocco, and the Crimea would eventually overcome any static defense, Zaragoza reasoned. Instead, he planned a surprise counterattack. He assigned Brig. Gen. Miguel Negrete’s 1,100-man brigade to defend the northern line from the forts and breastworks of Loreto and Guadalupe hills, and kept the remaining 3,550 troops to envelope the enemy in a counterattack once Lorencez had committed his troops to an all-out assault. Assuming that this would be against the less well-fortified eastern perimeter, Zaragoza had a small infantry detachment and two field pieces advance east of the city to lure the enemy into the trap.

Zaragoza stationed his best troops on the east side. These were the First Brigade of Oaxaca, under Brig. Gen. Porfirio Díaz, and the Batallón de Zapadores (sappers, originally, but now elite infantry), under Brig. Gen. Francisco de Lamadrid. Lamdrid would also control the Reforma de San Luis battalion and the Permanent Battalion of Veracruz, linking the eastside defenses with Fort Guadalupe. Two smaller brigades, Brig. Gen. Felipe Berriozábal’s Cazadores (light infantry) and the Michoacán Brigade of Brig. Gen. José Rojo, waited in city plazas, ready to advance either north or east. A fourth column, the cavalry under Brig. Gen. Antonio Álvarez, waited with a mountain battery near Fort Loreto to exploit any temporary confusion in the enemy ranks. Zaragoza located his own headquarters with Díaz.

City defense commander Brig. Gen. Santiago Tapia would cover the rest of the perimeter forts and barricades with two Michoacán infantry companies and Puebla’s three Guardia Nacional battalions, augmented by civilian volunteers mobilized in the previous 48 hours. For a general reserve, Zaragoza held the Rifleros de San Luis Potosí battalion, a field artillery battery and two mountain batteries in central locations. Beyond the defense perimeter, a couple of mounted guerrilla bands advanced east to distract the enemy. When the enemy was in sight, a peal of alarm from Puebla Cathedral’s biggest bell would be rung, and a single cannon shot would signal imminent attack.

On May 5, the French left Amozoc at 5 am and bivouacked at Hacienda Amalucán, three miles east of Puebla. Scouts posted on Amalucán hill failed to detect the defensive activities around Puebla. Lorencez sent his battalion of Chasseurs d’Afrique, under Colonel Valeze, to reconnoiter the approach and locate suitable artillery positions. The horsemen, resplendent in white turbans, short light-blue jackets and red pants, were continually harassed by mounted Mexican guerrillas in ranchero garb, firing their rifles and retiring when charged. Despite the harassment, Valeze managed to find a position 2,700 yards from Fort Guadalupe from which the guns could cover the infantry’s advance.

Lorencez Begins His Campaign for a Glorious Victory

Around 9 am, lookouts in Puebla’s church towers spotted French infantry debouching onto the plain from Amalucán, their fixed bayonets glinting in the morning sun. Zaragoza sent a cavalry squadron to confront them and determine their objective. It was the fortified hills of Loreto and Guadalupe. Lorencez was looking for a glorious victory, not necessarily an easy one.

Lorencez, meanwhile, had halted to enjoy a coffee. The morning was clear, fresh, and invigorating, and Almonte and others had sworn that Puebla would throw out the Liberals and strew flowers on the French troops coming to save Mexico. Suddenly a tolling bell from the distant cathedral interrupted his reverie, growing louder as bells of many of the city’s 150 churches joined in. At 10:15, Lorencez heard the dull thunder of a cannon shot rolling across the plain. Was Puebla being defended? For a moment Lorencez felt deceived. Then, confident of his troops’ innate superiority, he ordered the advance to continue.

As Zaragoza watched, a small French detachment split off to the southwest under cover of a low rise, while the bulk—4,000 to 5,000 infantry, accompanied by artillery—continued on to a ranch 1,500 yards north of Guadalupe hill. He had guessed wrong. Lorencez was not taking his bait, but instead was directing his main effort at Guadalupe. Zaragoza immediately ordered Lamadrid’s Zapadores and Berriozábal’s Toluca brigade to reinforce Negrete at the double-quick, while Negrete advanced a battalion toward the approaching French to delay them until the reinforcements arrived.

At 11:45 the French artillery opened fire on Fort Guadalupe, confirming Zaragoza’s surmise. The four rifled 4-pounders of the Marine Artillery battery were too light to damage the fort’s stone walls, but shells from the provisional battery of 12-pounder mountain howitzers dropped within the fort, wounding several men. Guadalupe’s ancient pieces lacked the range to reply. Dissatisfied, Lorencez ordered the guns to move up. But the closer position had a restricted view of the target, and after 45 minutes the artillery had expended half its ammunition without a single shell hitting the fort or causing casualties. Disgusted, Lorencez halted the bombardment and ordered the infantry into the assault.

While the French artillery was wasting its ammunition, Zaragoza’s realignment of the northern defense line was completed. Negrete abandoned Fort Loreto and shifted his two battalions and the Permanent Battalion of Veracruz to the right, strengthening the breastwork defenses near Fort Guadalupe. Berriozábal’s brigade filled in on the left, and the 6th Batallón de Nacionales de Puebla moved forward of the breastworks to a blocking position. Zaragoza warned Guadalupe’s commander, Colonel Jesús González Arratia, that the fortress was Lorencez’s prime objective. González had only two small green battalions, the Mixto (Mixed Battalion) de Querétaro and the Cazadores de Morelia; Zaragoza managed to send him two more Querétaro companies and a mountain artillery battery.

The Mexicans Repel the First Attack

Lorencez badly underestimated the Mexican capacity for resistance, initially committing only two battalions of the 2nd Regiment of Zouaves to the assault on the northern defense line. One battalion of the 2nd Regiment of Marine Infantry followed to provide reinforcement and cover their open right flank against Mexican attack from Fort Loreto. Lorencez kept back a large reserve consisting of the 99th Regiment, the 1st Battalion of Chasseurs de Vincennes, a battalion of Marine Fusiliers, and the mounted Chasseurs d’Afrique.

Shortly after at 11 am, the first battalion of Zouaves, with the marines behind them and to the right, hit the breastwork line near fort Guadalupe. The second battalion assaulted Fort Guadalupe directly. By an irony of fate, these “superior” men of the Comte de Lorencez suffered their first setback at the hands of an “inferior” race—full-blooded Mexican Indians. The 6th Puebla, 600 Indians of the Sierra de Tetela, Xochiapulco and Zacapoaxtla, stood their ground impassively, holding their fire until the enemy was almost at point-blank range. Then they fired a volley and fell back, reloading and firing until they had rejoined the main defense line.

With the enemy only 15 paces away, General Negrete climbed onto the breastworks and lifted his cap as a signal. A volley of musketry crashed into the ranks of Zouaves, bowling over dozens. They halted, stunned. Then Negrete cried out, “In the name of the Fatherland, up and at them, muchachos!” and leaped over. Cheering and yelling, the Veracruz battalion followed him. Seeing this, the Cazadores sallied out from the fort. Then Berriozábal’s Tolucans closed in on the left, opened fire and charged; Rojo’s Michoacán brigade did the same on the right. Before long, black-powder gunsmoke had enveloped the battlefield in a dense fog. Pressed from both sides as well as in front, and taking casualties amid smoke and confusion, the French retreated to their starting positions.

France’s Second Wave Breaks Through, Briefly

The French quickly reformed their lines and by 12:30 pm were ready to resume the attack. This time Lorencez formed his assault force in three columns: the Zouaves and 1st Battalion of Chasseurs de Vincennes would assault Guadalupe hill, while the 99th Line and the marines advanced against the center and left, respectively, of the breastwork line. Zaragoza committed the Rifleros de San Luis, situating them to cover the south flank of Guadalupe hill. The 6th Puebla moved back to its advanced position, while the Toluca and Michoacán brigades and the Veracruz battalion manned the breastwork line between the forts with Negrete’s battalions.

On the Mexican left, heavy fire from the 6th Puebla, 6th Michoacán, and Veracruz battalions twice repelled the Zouaves and Chasseurs, while the Tolucans battered and drove back the French marines. Some Zouaves of the first battalion, however, charging up Guadalupe’s slopes in a hail of musket fire, reached the fortress walls. Boosted on their comrades’ muskets, they scrambled onto the parapets, penetrating to the central courtyard in wild, hand-to-hand fighting. The old soldiers of Veracruz manning Guadalupe’s battery, having given up their small arms to equip volunteers, fought back with whatever came to hand, including cannonballs. At least one unfortunate Zouave who grabbed the muzzle of a cannon to hoist himself over the parapet had his head smashed in by a cannonball hurled by an unarmed Mexican gunner.

The Querétaro battalion, civilians only a month before, fled the parapets and ran into the courtyard ahead of the Zouaves. The French thought the fort was theirs. Then Colonel González threw himself into the midst of the stampede, sword in hand, and started to berate the deserters. At that moment, hoarse shouts of “Viva la República!” rang out over the din of close combat as the Reforma battalion surged past the fortress walls. Reassured and encouraged, the Querétaro recruits turned on their pursuers with fanatical fury. The Zouaves on the parapets, realizing that the counterattack was cutting off both reinforcement and retreat, leaped from the walls and ran down the hill. Several took refuge in the chapel, where they were taken prisoner.

France’s Third, and Final, Attack

Lorencez had told his staff they would meet in Guadalupe, and he would not be denied, even though he had now taken some 300 casualties. Ordering a third attack for 2 pm, he organized most of his force into two assault columns, one consisting of the battalions repulsed in the second attack, the other comprising the Regiment of Marine Infantry under Colonel Hennique, part of the Chasseurs de Vincennes, and the Chasseurs d’Afrique, some 3,000 men in all. While the first column attacked Guadalupe, the second would stage a diversionary attack against what the French general assumed, with little if any reconnaissance, was the city’s lightly defended eastern side.

Fearing that one more determined French assault would carry Guadalupe, Zaragoza ordered his friend Felipe Berriozábal to stop the French assault column by attacking its right flank with his 500-man Cazadores de Toluca brigade and the Batallón Reforma de San Luis. Berriozábal, who as an 18-year-old lieutenant had fought against American General Winfield Scott’s 1847 invasion, was disgusted to find the Reforma men resting on Guadalupe hill oblivious to the approaching enemy, their colonel so drunk that he had to be taken by two soldiers to the rear. Livid, Berriozabal reprimanded the idle troops, shouting, “Is there no jefe of honor here who’ll take the lead?” A captain stepped forward: “jefe no, but a capitán of honor there is.” The general gave him the battalion. As the Zouaves and Chasseurs started up the slope, Berriozábal’s battalions closed in on their right and opened fire. The third bloody assault, taking more casualties, ground to a halt.

Hennique’s column approached Puebla’s eastside defense line, and Díaz’s and Lamadrid’s men opened fire. The weight of the large French column pushed the Mexicans back into the barrio of Misericordia. In Xonaca, the French broke through the Zapadores’ street barricades, and intense, close-quarters fighting swirled among the houses and around the church. In Los Remedios, the Oaxacans had fortified themselves in a large brickyard. Firing lines seesawed back and forth and bullets hummed like bees above the sweating combatants. One bullet fatally struck 2nd Lt. Manuel González, who was carrying the 2nd Oaxaca Battalion’s flag. As he fell, Captain Varela snatched up the banner. Then Valera, too, went down, still clutching his battalion’s ensign. Captain Crisóforo Canseco, the company commander, picked it up and handed it to 2nd Lt. Domingo Loaeza, who proudly carried it to the end of the battle, when he counted five bullet holes in the flag and one in the staff.

In the confusing fights among the brickyard’s kilns and stacks of bricks, neither side seemed able to gain traction. Suddenly a 35-man guerrilla band roving outside the defenses opened a heavy fire on the French rear from the cover of a stone fence alongside the road to Amalucán. Thinking they were being outflanked, the attackers paused and started to take up a defensive posture. Seizing the initiative, the Zapadores rallied and counterattacked Hennique’s right flank. Under fire from front, flank, and rear, the French troops slowly fell back.

Once Lorencez had committed a column against Puebla’s eastern defenses, Zaragoza sent Álvarez’s cavalry, waiting near Fort Loreto during the first two assaults on Guadalupe, to Díaz. As he saw the French starting to retreat, Díaz ordered Álvarez to charge with the lance, which virtually all Mexican cavalrymen used, before Hennique could regain control. The sudden appearance of 650 saddle-hardened warriors, clad in ornamented leather outfits with broad hats over colorful bandannas and huge spurs on high-heeled boots, turned the already fracturing formations into all-out flight. The French troops recovered only after a wide, deep ditch stopped the pursuing horsemen. Using this respite, they regrouped in a single large defensive position just beyond effective range of Zaragoza’s artillery.

At 5:49 pm, Zaragoza telegraphed the minister for war in Mexico City and briefly recounted the three failed assaults by the French. He concluded, “At this moment they are drawn up in battle order with a strength of 4,000 and some, facing [Guadalupe] hill, a gunshot distant.” The French advanced again and the Mexicans opened fire. Suddenly, lightning flashed, thunder crashed, and a tremendous hailstorm, freakish but providential, stopped the haggard French troops in their tracks. The hail turned into rain, leaving the muddy slopes of Guadalupe hill too slippery for a further charge. Lorencez ordered his exhausted and dispirited soldiers to withdraw to their bivouac.

Zaragoza Great Moral Victory

In his telegram, Zaragoza had estimated the enemy losses at 600 to 700 killed and wounded. After a careful count, Mexican casualties were reported as 83 killed, 132 wounded and 12 missing. Lorencez variously reported 462 or 476 killed, wounded or missing, but some historians have estimated over 1,000 French casualties. Zaragoza had no reason to exaggerate the French losses; he had won a stunning and unexpected victory. Lorencez, on the other hand, may have been trying to minimize the true extent of his losses to the emperor. After committing France’s military prestige to taking Mexico City, he had failed completely, while squandering up to 16 percent of his whole force in Mexico.

Zaragoza longed to destroy the French invasion force in a counterattack, but told the minister for war in his telegram, “I am not fighting as I would desire because, as you know, I do not have enough strength for that.” The French still outnumbered him, and, because of the San Andrés disaster, the Mexicans’ ammunition supply was low. Zaragoza knew he had been lucky. He had won a great moral victory at Puebla, and nothing could be allowed to risk dimming its luster. Lorencez waited for another two days, then on May 8 he began his doleful retreat to Orizaba.

Assessing the battle the next day, Zaragoza wrote, “I can affirm with pride that the Mexican army did not once turn its back on the enemy.” He added, “The French troops conducted themselves with valor in the attack; their commander conducted himself with torpor.” Lorencez, for his part, blamed the defeat on the French minister, Saligny, sarcastically telling his troops: “We had been told a hundred times that the town of Puebla called for you with all their hearts and that the inhabitants would rush to follow you as you marched and to cover you with flowers. It was with the confidence derived from these false statements that we appeared before Puebla.”

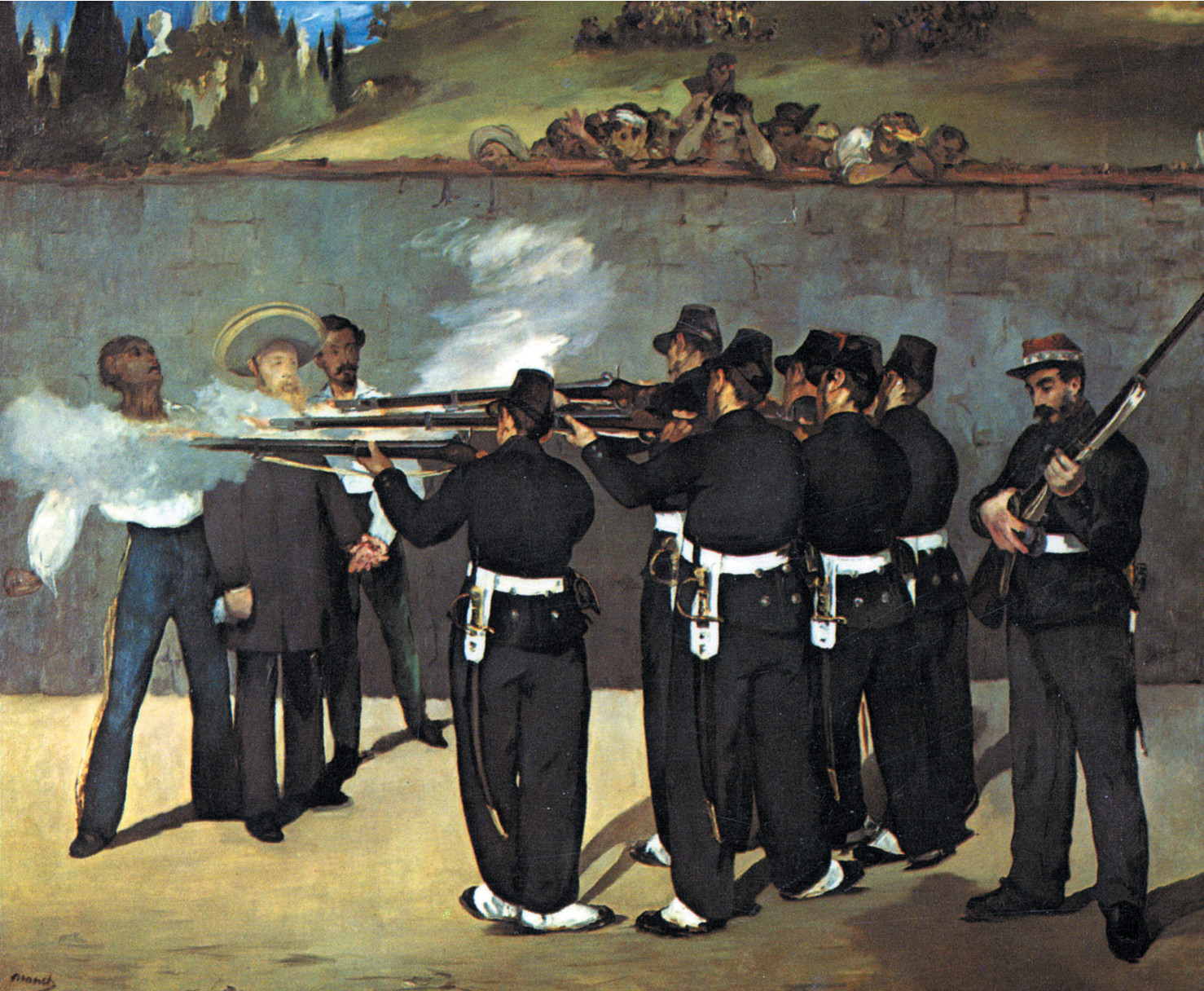

The following year the French returned with a much larger army under a new commander, took Puebla in a three-month siege, and marched unopposed into Mexico City to seat Maximilian on his long-anticipated throne. Zaragoza didn’t live to see it, having died of typhoid four months after the Battle of Puebla on the Cinco de Mayo, 1862. Nevertheless, his victory bought a year’s respite, during which time Juárez prepared his government and guerrilla organizations to resist the French occupation. The Cinco de Mayo battle showed Mexicans that the French army was not invincible. Zaragoza had written prophetically, “Very soon the usurper of the French throne will be convinced the era of conquests has already passed by.” In the summer of 1867, after heavy American diplomatic and military pressure, the usurper brought his last troops home, consigning Maximilian to a Mexican firing squad and his own Grand Design for the Americas to the trashcan of history. Three years later, after a crushing defeat by the Prussians at the Battle of Sedan, Napoleon III’s Second French Empire would join it.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments