By John Domagalski

The early months of 1942 were dark days for the United States Asiatic Fleet. Much smaller than the Pacific Fleet, and equipped with mostly outdated surface ships, the fleet was in no way capable of winning a serious confrontation with the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Being based in the Philippines, however, meant that Admiral Thomas C. Hart’s Asiatic Fleet stood directly in the path of Japan’s southward expansion. Japanese bombers demolished the Cavite Navy Yard near Manila just days after the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. Much of America’s land-based airpower that was to support the naval units had also been wiped out.

With the loss of the main operating facility and the Philippine defenses crumbling in the face of a Japanese invasion, most of Hart’s surface units were able to escape south to the Netherlands East Indies. The ships, unfortunately, were to fare no better in Dutch waters.

In February, the beleaguered Allies decided to combine naval forces in Southeastern Asia. American, British, Dutch, and Australian (ABDA) warships formed into a hastily assembled fleet only to be soundly defeated in three battles—Flores Sea (February 4), Badoeng Strait (February 19/20), and Java Sea (February 27).

By March, most of the Allied surface forces had been swept aside, American land forces were backed into a small corner in the Philippines, and Singapore, the large British base in Malaya, was under a Japanese flag. Imperial forces were now streaming unchecked into the Netherlands East Indies.

Submarines of the Early Pacific War

During the first, difficult months of the Pacific conflict, American submarines represented the only formidable offensive weapon available to the Asiatic Fleet. Starting the war with 29 boats, the fleet was a mix of smaller, outdated vessels and newer fleet subs. The underwater craft were as prepared as could be for combat, having had trained under wartime conditions for several weeks prior to the start of hostilities.

With the loss of the Philippines, the submarines were forced to operate from meager facilities. Supplies and spare parts were limited, with many of the latter having been lost during the Cavite raid. Several submarine tenders provided a moving base that shifted among various locations, sometimes staying just ahead of the Japanese.

The U.S. submarine force in the Pacific was mostly deployed with the aim of stopping Japanese invasion fleets, and December 1941 found many of the subs roaming the waters around the Philippines. The force then shifted south, eventually setting up camp in Australia.

In early 1942, the boats conducted a variety of operations. Many were arrayed in the defense of the Netherlands East Indies, while some were called upon for special missions to the American fortress island of Corregidor near Manila Bay.

During these early operations, Asiatic submarines both sustained losses and sank some enemy shipping. In the first four months of hostilities, the Sealion, Shark, and Perch were lost to enemy action, while the S-36 ran aground and was scuttled. During the same timeframe, the submarines were credited with sinking 10 Japanese ships.

The Seawolf

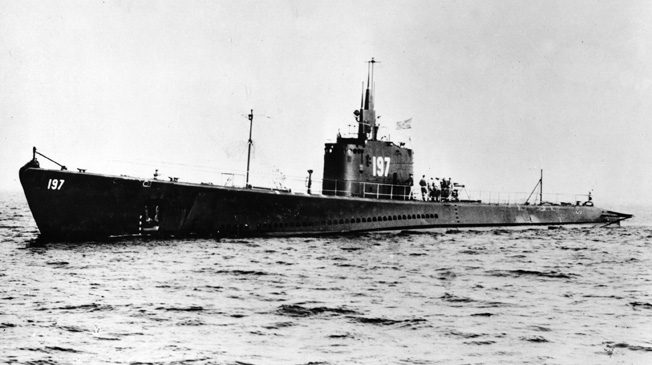

Lieutenant Commander Fred Warder and his submarine Seawolf (SS-197) were in the thick of action from the start of the Pacific War. Warder had been with the boat since he put her into commission on December 1, 1939, at the Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Navy Yard.

Displacing 2,350 tons, Seawolf was the last of the four Sargo-class vessels to be completed. Warder’s boat had a crew of approximately 55 officers and enlisted men, stretched 311 feet, and could make 20 knots on the surface and just under nine submerged. She carried 24 torpedoes; four torpedo tubes pointed forward and an equal number were at the stern. After a workup in the Atlantic and Caribbean, the vessel reported to San Diego to become part of the Pacific Fleet. In the fall of 1940, Seawolf was assigned to the Asiatic Fleet and traveled west to Manila, where she was in port when the war started.

Warder hastily put to sea on December 8, leaving the harbor before Japanese planes plastered Cavite two days later. On his first war patrol, Warder took his boat into the waters off the northeast coast of the Philippines but came up empty after spending 18 days at sea, in spite of a daring attack on a Japanese ship in Aparri Harbor on the northern coast of Luzon.

Warder then left the Philippines on December 31 bound for Australia. Considered the submarine’s second war patrol, no enemy ships were sighted during the voyage.

Seawolf’s third war patrol was a special mission. She pulled out of Darwin on January 16 loaded with .50-caliber machine-gun ammunition bound for Corregidor. While en route she came across a Japanese convoy but could not gain a favorable firing position because of foul weather. She arrived at the embattled island on January 27 and promptly discharged her cargo. She took aboard 16 torpedoes, an assortment of submarine spare parts, and 25 passengers for the trip out. Warder was not going back to Australia but instead set a course for Surabaya, Java.

The Battle of Java Sea

The mid-afternoon of February 15 found Seawolf once again underway. Slowly moving on the surface out of Surabaya, the submarine was joined by a patrol vessel that guided her through nearby minefields. By 5:00 pm, the submarine was proceeding alone in a northerly direction at 17 knots on her fourth war patrol.

Most of the voyage was spent in the waters around Java, where the American submarine fleet was again being called on to try to slow approaching Japanese invasion forces. On February 19, Seawolf crossed paths with Japanese ships near the island of Bali, directly east of Java. Warder maneuvered his boat to attack and fired torpedoes at two transports. He scored no hits, but underwent a harsh depth charging for his effort.

Seawolf again found Japanese ships near Bali on February 25 in the Badung Strait. Her skipper fired torpedoes at a transport and destroyer; he reported seeing one torpedo squarely hit the transport, and the sonar operator reported two explosions on the destroyer. Warder rigged for a depth charging, believing that he sank one or both enemy vessels. Postwar records, however, report no Japanese ships sunk during this encounter.

In spite of his skill and determination, Fred Warder so far had no results to show for his efforts.

The American submarine force’s effort to forestall the Japanese invasion of Java had failed and, during the last days of February, Allied surface ships were defeated in the Battle of Java Sea. The Japanese began to land troops on the island almost immediately. Twelve American submarines remained in the area to do whatever damage possible to Japanese shipping. Seawolf and Pike (SS-173) were directed to patrol south of Java in search of Japanese carriers thought to be operating in the area. Neither submarine was able to find the enemy flattops.

The Imminent Invasion of Christmas Island

By late March, Warder and Seawolf were nearing the end of their long patrol, and just in time, too, for the arduous voyage was beginning to take its toll on the crew. Many of the sailors had not seen topside for much of the patrol. Nerves were frayed and tempers stretched. With supplies of cigarettes running low, some of the men resorted to smoking coffee grounds wrapped in toilet paper.

Warder was to have one more encounter with the enemy. On March 14, 1942, Japanese Imperial General Headquarters issued orders for the occupation of Christmas Island. Situated almost 200 miles straight south of the west end of Java, the tiny landmass in the Indian Ocean was under British control. The island was rich in phosphates, a much-needed material for the Japanese war machine.

In the last days of March, a small force of Japanese ships set sail from Bantam Bay, Java, on a course for Christmas Island. The fleet consisted of three light cruisers, eight destroyers, an oiler, and two transports. Embarked on the latter were the 850 troops of the occupation force. Flying his flag on the light cruiser Naka, Rear Admiral Shoji Nishimura was in command of the operation.

Another American submarine had picked up the Japanese invasion fleet and radioed a contact report while Seawolf was operating near Sunda Strait off the west end of Java. Late in the day on March 27, Warder received a coded message directing him to proceed to Christmas Island and then return to port in Australia.

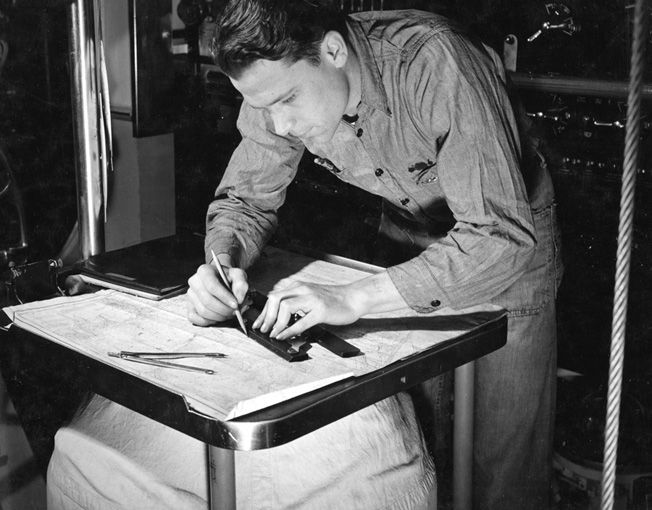

Surfaced at the time for a nighttime battery recharge and running on diesel power, Warder increased speed to 14 knots and began the journey south. The submarine stayed on the surface for speed until just after 6:00 am when she dove and ran at periscope depth for the balance of the day. During the journey, Warder studied his navigation charts of the area, plotting possible routes that the Japanese might use to close on the island.

Seawolf returned to the surface early in the evening. At exactly midnight, after traveling 190 miles that day, lookouts spotted Christmas Island 25 miles off the starboard bow. Fred Warder’s submarine and Admiral Nishimura’s ships were on a collision course.

Seawolf cautiously approached Christmas Island during the first hour of March 29. “Commenced steering various courses to round island to starboard at eight miles,” Warder later wrote in his log. “Sky is overcast, but moon is providing excellent visibility.” The skipper wanted to carefully look over the island to determine whether or not it was still in friendly hands and to check for possible Japanese landing sites.

A Target-Rich Environment

At 6:18 am, Seawolf dove to periscope depth near the northwest point of the island. The next area to be reconnoitered was Flying Fish Cove, a small inlet positioned on the north side of the island. It was here that Warder spotted a ship that appeared to be partially sunk. Peering through the periscope, he could make out a gray hull and yellow smoke stack on the vessel. He estimated the ship at 8,000 tons. Warder nosed the submarine closer, eventually closing to about three miles off the entrance of the cove. “No other shipping in cove,” Warder noted. “No activity apparent in settlement or on dock.” Seawolf pulled back and ventured to the southern part of the island.

At 2:15 pm on March 30, a large seaplane was sighted flying over the northern part of the island at an altitude of about 1,500 feet. Whether it was friend or foe was not known. The plane apparently did not see the submerged submarine. After spending the day submerged and carefully surveying the island, Warder brought his submarine to the surface just before 8:00 pm. There was no sign of the Japanese.

“I have now decided that [Flying Fish] Cove is only practical place for landing attempt,” he concluded. “Other possibilities are impractical due to deep water close to shore, cliffs and rocks, wooded banks, heavy swells, and small landing areas.” The skipper decided to patrol along an 11-mile-long line that was 61/2 miles off the entrance to the cove. Although an occasional light rain squall passed through the area, the night was mostly well illuminated by moonlight, providing good conditions for the lookouts. Warder felt it was a perfect position to intercept any Japanese ships that might be approaching the island. His hunch would soon be proven right.

Just after 6:00 am on March 31, Seawolf, still on the surface from her evening battery charge, slowly came to a stop. Listening intently, the sonar man reported enemy ships pinging somewhere off the port side. Warder had just ordered Seawolf to submerge when a searchlight suddenly appeared off the starboard beam. The sonar man soon reported pinging in all directions and then the sound of a ship’s screws approaching fast—a single Japanese destroyer was bearing down on the submarine from 3,000 yards away.

Warder commenced evasive maneuvers and ordered the vessel down to 200 feet; two depth charges exploded as the submarine dove. A few minutes later, a determined string of 10 depth charges exploded with a thunderous roar. Thankfully, the underwater barrage was brief—only about half an hour. Just before 7:00 am the next day, Warder ordered periscope depth so that he could take a look. He found the sea loaded with Japanese ships––a “target-rich” environment.

Scanning the area, Warder found a destroyer about 6,000 yards away, two transports about 8,000 yards off the port side, and a light cruiser 7,000 yards in the same direction. A second light cruiser was slightly farther away to starboard.

As fast as Warder yelled out the bearing of each sighting, a young ensign worked hectically to write down all of the contact information. As the morning progressed, Warder eventually sighted all three of the Japanese light cruisers, four destroyers, and the two transports. Using the silhouettes in his identification book, Warder noted that two of the light cruisers were of the Natori type, while the other one looked to be of the Jintsu class. There was no question that the Japanese invasion was well under way.

Perfect Conditions For an Attack

Warder decided to head first for the cruiser on the port side. “These birds are all just milling around except the APs [transports] are headed for the cove and are too far west of me to get at them,” he recalled. A short time later he changed course to see if he could catch one of the transports. “It doesn’t look like we can get him,” he quickly determined.

Focus then shifted back to the cruisers, which seemed to be patrolling off the entrance of the cove. Carefully studying the enemy vessels, Warder noted that all of their seaplane catapults were empty; the seaplanes were apparently off supporting the landing operation. He noted the long clipper bow with a chrysanthemum or flaming-sun figurehead on the Jintsu-class cruiser. Based on the number of messages that were being flashed to other ships, the vessel appeared to be the flagship. Warder’s identification and assumptions were correct: the Jintsu-class cruiser was in fact Admiral Nishimura’s flagship Naka.

When Seawolf increased speed to close on the cruiser, it turned away, so Warder decided to edge closer to the entrance of the cove. There were now four ships, two destroyers, and two light cruisers, all pinging at once; apparently the Japanese could not find the submarine.

“Surface of water is nicely rumpled, with occasional whitecaps,” Warder wrote of the ideal conditions to hide his periscope. In the minutes before 8:00 am, two distant explosions were heard and two seaplanes were spotted flying over the cove. Warder temporarily submerged to 120 feet to move closer to the cove before again coming up to periscope depth. Over the course of the next hour, Seawolf silently stalked the Naka, occasionally repositioning after the cruiser turned away from the submarine on several occasions.

The Seawolf‘s Attack

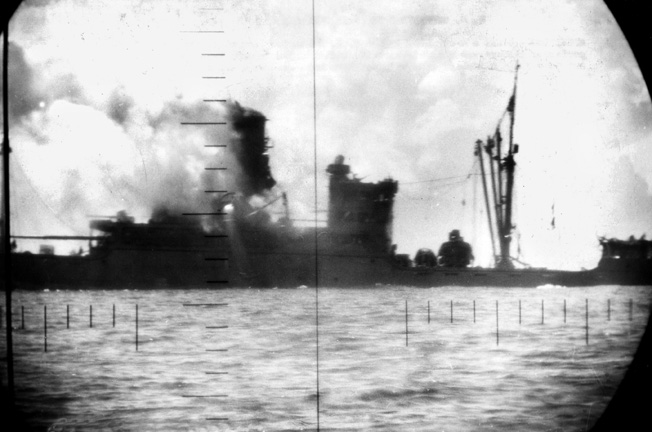

Shortly before 9:00 am, it was finally time for the Seawolf to attack. The speed of the submarine slowed to 21/2 knots as Warder made a final observation through the periscope. He noted that the target was 1,400 yards away and moving at a speed of 15 knots. It looked as if the Naka was slowly turning toward him, so Warder gave the order to open the outer torpedo doors.

Manning the firing controls, Henry Bringelman chimed up to say that everything was ready on his end. At exactly 8:48 am, four torpedoes left the forward tubes of Seawolf in a firing sequence that lasted exactly one minute. Set to run at a depth of 10 feet, the fish were aimed at the cruiser’s bow, stern, foremast, and mainmast.

Warder took one last look before going deep. “I can [sic] see smoke from torpedo tracks drifting across field of vision,” he later wrote of the moment. “Observed men to be running and shouting on cruiser quarterdeck and measured range as 700 yards.” Seawolf increased to full speed, turned sharply to the right, and began a plunge down to 120 feet.

All the submariners could now do was wait to hear the results of their attack and brace themselves for the enemy’s response. “It seemed like a year to me,” Warder wrote of the waiting. The commanding officer soon clearly heard an explosion. “A number of people insist there were two explosions. I only heard one.” The propeller noises from the cruiser seemed to stop.

Seawolf’s crew believed that they bagged a good target. However, postwar analysis does not support any Japanese ships being damaged or sunk in the area on that particular day. It is possible that the torpedoes may have malfunctioned or exploded prematurely.

“We’re Going to Have One Helluva Time”

Within a few minutes of diving, there was a string of eight nearby explosions thought to be depth charges, prompting Warder to take the boat down to 200 feet. As he descended the ladder from the conning tower into the control room, the hatch was closed and tightly sealed above him. But the dive did not go without problems.

“Couldn’t open flood valve against sea pressure,” he logged. Shifting to hand power, crewmen were able to open the valve, but blew a gasket in the process. It did not bode well for what was certain to be a determined Japanese counterattack. “We’re going to have one helluva time,” predicted Warder.

A ship moving at high speed was heard to approach the submarine from the starboard beam. At almost the same time the sonar operator reported a series of minor, distant explosions. Five more depth charges then went off some distance away. A minute later, seven more exploded much closer off the stern. The enemy was getting the range.

For the next 71/2 hours, a cat-and-mouse game ensued. “Every time a pump runs, they come in on us,” Warder lamented about the sub’s inability to hide. “We pump until somebody starts for us; then we stop. Trim pump makes an awful racket, due to air-binding and high discharge pressure.”

With each explosion, Seawolf shook and shuttered, sending cork and paint chips sailing through the stale interior air. Occasionally the lights dimmed. Chief Radioman Joseph Eckberg sat in the radio shack listening as the depth charges came closer and closer off the starboard side. He thought it was impossible that one would not be a direct hit. The heavy pounding totaled 25 depth charges. The submarine survived, but the depth charging started to take a toll on Seawolf.

Among the first problems was an engine lube oil cooler that went out. “Saltwater is slowly filling the engine sumps due to leaky overboard circulating water valves,” Warder reported. “Two gyro repeaters went out; radio transmitter went haywire; value wheels flew around the engine rooms.” Cable tubes in the conning tower were beginning to leak as did one of the stern torpedo tubes, and the crew worked hard to keep the damage from causing even further problems.

“Everybody … carried bilge water to sanitary tanks to keep electrical machinery from being damaged,” Warder recalled. The submarine slowly turned to the northwest, away from the ships above.

Recuperation

During the mid-afternoon hours, Seawolf appeared to have successfully slipped away from her Japanese hunters. Warder, however, remained very cautious. He alternated between staying deep and coming up to periscope depth for a quick look. A scan just after 3:00 pm found no Japanese ships in the immediate area. Rain was spotted forming to the west of Christmas Island and a squall or cloud of smoke seemed to be hovering over Flying Fish Cove.

At 7:49 pm, Seawolf surfaced to begin her nightly battery charge. Once topside, the crew found the deck shelter light burning. It was quickly disconnected and would remain so for the remainder of the voyage. The ship’s bell was also found to be broken, perhaps a casualty of the depth charging. Warder, unsure if the Japanese were still in the area, transmitted a contact report and then pointed the ship east to pass north of the island. He noted, “Decided to obtain a position ten miles east of Christmas by 5:00 am so as to approach it in the moon’s shadow and dive just behind Northeast Point about 6:00 am for a look around in the cove.”

Later that evening, Seawolf crash-dived when a lookout sighted two torpedo tracks approaching the starboard side. The sonar operator, however, was unable to pick up any accompanying noises, so it is probable that there were no actual torpedoes.

“I had observed similar phenomenons [sic] the night before in this general area; definite streaks of refuse material probably washed off the island by the spring tide and drifting to the northwest in the prevailing current,” Warder concluded.

About half an hour before midnight, Seawolf received a congratulatory radio message from headquarters for the good day’s work. “It helped a lot,” Warder recalled. “We were feeling pretty well beaten down, so we put it on the bulletin board.” He attached a handwritten note personally thanking the crew for their hard work and devotion, also adding that he hoped to be with them on the next patrol.

The skipper had just drifted to sleep when the officer of the deck announced that a ship had been sighted about 10 miles away off the northern coast of the island. After intently studying the vessel through a powerful telescope, the officer of the deck concluded that it was an Asasio-type destroyer. Seawolf drifted to a halt as lookouts kept a careful eye on the enemy vessel that eventually turned away. A later sighting of a light cruiser convinced Warder to modify his original plan. He would now move 20 miles east of the island and attack the Japanese ships in the afternoon.

Another Attack by the Seawolf

However, the submarine was running low on torpedoes. Only one torpedo remained forward, but it had an air leak that amounted to 500 pounds per day and had previously been taken out of the tube as a safety precaution. “We have five torpedoes remaining aft which are in good shape, we think,” Warder noted, hopefully. With plenty of targets in the area, he would have to make his last shots count.

The plan for an afternoon attack was abandoned when Seawolf encountered the silhouette of a light cruiser at 3:35 am. “Ship sighted is slowly circling,” Warder wrote in the log. The Japanese warship appeared to be unaware of the surfaced submarine. About half an hour after the initial sighting, the vessel began a slow turn that put it on a heading directly toward Seawolf.

The range at the time of sighting was about 6,000 yards, but the ship was closing at a speed of about 11 knots. Warder took his boat to periscope depth and began maneuvering for a stern shot. He identified the target as a Natori-class light cruiser, making it either the Natori or Nagara.

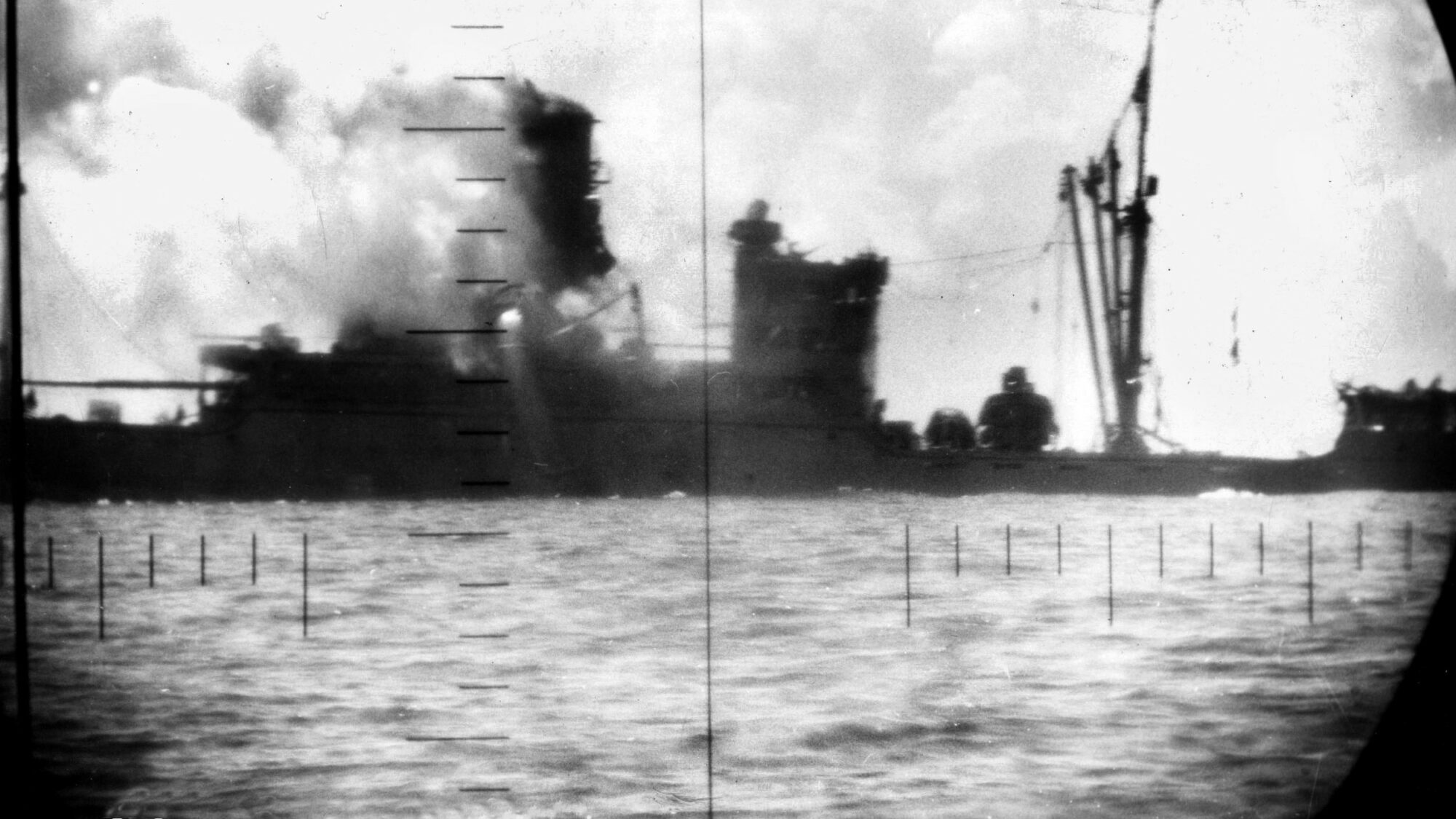

After more than half an hour of maneuvering, Warder was satisfied that he had a good firing set up. When the range to the target ship was down to about 1,700 yards, a spread of three torpedoes left Seawolf’s stern tubes. Set to run at a depth of 10 feet, the three underwater missiles streaked toward the unsuspecting cruiser. A terrific explosion shook the sub after only a minute. Staying at the periscope, Warder strained to the see the results of his attack in the dark. “Moon is obscured and observation becoming more difficult,” he reported. “I did not see him use his searchlight, nor did I see flames.”

He did, however, see what appeared to be heavy, black smoke. Warder believed Seawolf was making the Japanese invasion of Christmas Island a costly undertaking.

The speed of the light cruiser seemed to be slowing and her screws were thought to have stopped. At the same time that the warship disappeared from sight, sonar reported high-speed screws. Another light cruiser soon came into sight.

“This is other Natori, which has come out from Northeast Point,” Warder concluded. The sonar man estimated her speed at 30 knots. Only one torpedo was loaded in the stern tubes; the other remaining torpedo aft was not able to be made ready to fire due to a problematic angle setter.

With the target zigzagging at high speed and unable to fire a spread, Warder decided not to attack. He ordered the boat down to 150 feet as four depth charges exploded at some distance. The sound man reported many screws and three ships pinging, but none were close. The deep dive did not last long; Warder brought Seawolf back to periscope depth and caught a fleeting glimpse of the light cruiser disappearing over the horizon. No other ships were visible. The crew secured from battle stations just as the morning light began to show.

For a second time in two days, the crew of the Seawolf had executed a daring attack against an enemy warship, and Lt. Cmdr. Warder once again believed that he had seriously damaged or sunk a light cruiser. Postwar analysis, however, again did not record any Japanese ship being damaged or sunk at that time or place.

Striking the Naka

Seawolf spent the bulk of April 1 stalking various targets. Throughout the day Warder kept a careful eye on the two light cruisers and four destroyers that occasionally came into view, even noting the comings and goings of the cruisers’ floatplanes. He was, however, unable to gain a favorable attack position for most of the daytime hours. “As we would close one of them for attack, they would move somewhere else,” he recalled. “It was most maddening.” Flying Fish Cove remained the center of enemy activity.

By late afternoon, it looked as though the Japanese were getting ready to leave the area; apparently the landings had been a success. The two transports were building up steam in the cove in preparation for departure and many of the Japanese warships were making wide sweeps of the area. Warder decided to focus on Nishimura’s flagship, the Naka. He was convinced that he was attacking a different light cruiser than the one he had hit the day before.

To aid in his analysis, he pulled out and studied the 1939 edition of Jane’s Fighting Ships. It noted that not all of the Jintsu-class cruisers had clipper bows. “When periscope went up for firing observation, I had the feeling there was something vastly different about the bow,” Warder wrote. “At no time during approach did I comment on the figurehead which yesterday’s Jintsu possessed; nor did it ever come to my observation. On the day preceding, this figurehead distracted me at every observation.”

When four destroyers took up a rectangular formation around the light cruiser, Seawolf’s skipper knew it was time for an attack. All four destroyers were pinging, trying to locate any nearby enemy submarines, a final sweep before the departure of the transports.

Seawolf turned to bring her stern tubes to bear. At the same time the Naka made an unexpected zig toward the submarine. “This is where he made his mistake,” Warder said of the firing setup. At 5:02 pm, the last two aft torpedoes left the stern tubes of Seawolf. Given the four nearby destroyers, Warder was not taking any chances. He immediately ordered a turn to starboard to make a getaway and a depth of 200 feet.

A violent explosion was heard as the submarine started her descent, sounding as if one of the torpedoes had found its mark. “Sound did not hear this fellow’s propellers again and I feel sure we got him,” Warder concluded. “Judging by rapidity with which Natori sank this morning I do not think these [light cruisers] can take much.”

Seawolf’s efforts had finally paid off. An observer in a nearby Japanese destroyer saw a torpedo track racing toward the Naka. He then saw the light cruiser make a sharp turn, but it was too late. A single torpedo slammed into the starboard side of the flagship.

The Japanese Pursuit

The Japanese were not going to take the attack lightly. Some secondary explosions, presumably from the torpedo hits, were heard as the submarine tried to silently escape to the west. The men of the Seawolf were in for a long evening. “They gave us hell until near midnight,” Warder later wrote of the night. The depth charging started with three explosions, at a safe distance, that occurred at the same time the torpedoes were heard to hit the Naka.

Trapped together in the Seawolf’s seven compartments, crewmen braced for the worst. The air was stale and foul. When the air conditioning was turned off to reduce noise, the heat and humidity became almost unbearable. Crewmen and machinery alike dripped with sweat. Many sailors could do nothing more than sprawl out on their bunks and wait. The nauseating stench was only getting worse. People seemed to be moving in slow motion. Chief Pharmacists Mate Frank Loaiza passed out saline tablets, but they did not seem to help. Finally, the misery ended.

With the last depth charge having fallen an hour earlier, Warder believed that he had given the Japanese the slip and ordered periscope depth at 7:00 pm. But something went terribly wrong during the ascent. The forward trim tank had been incorrectly adjusted and, instead of a gentle rise, the submarine suddenly started shooting up to the surface. The top of the submarine’s conning tower broke the surface, creating a very visible spray of water; Seawolf was broaching. Warder immediately ordered an emergency dive and the boat began to descend, but not before attracting the enemy’s attention.

The Japanese seemed to be right on top of the sub. The first of a string of depth charges detonated at 7:33 pm. The explosions were close—too close for comfort. With Seawolf rapidly plunging to 200 feet, most of the remaining 18 depth charges were ineffective. However, battery power started to run dangerously low, so the submarine had to get away from her pursuers—and fast.

“We stopped everything except the gyro and an IC motor generator early in the evening,” Warder remembered. “What walking was done was done quietly; talking was only in whispers.” If the submarine could not make it to the surface for charging soon, the crew might never see the light of day again.

It sounded as if the main body of the Japanese fleet had moved out of the area, leaving one destroyer behind to keep the submarine down. “A sleeper stayed right over us, whom we couldn’t even hear in our sound gear, but he was listening to us. Every now and then he would drop one to four [depth charges] from a Y gun, putting on no speed whatsoever.”

Moving at a low rate of speed, Seawolf slipped away from her stalker. “There was not enough battery left for any more use of speed so we can only thank God for getting away. Good management on my part had nothing to do with it,” Warder confessed.

The sound of a ship pinging somewhere off the starboard quarter could still be heard when Seawolf went to periscope depth just after 10:00 pm. A scan of the area, however, showed no ships.

Out of functioning torpedoes and with his crew near exhaustion, Lt. Cmdr. Warder set a course for Fremantle, Australia. At half past midnight, Seawolf surfaced and headed west at full speed, making the much-needed battery recharge along the way.

Defeat on Christmas Island

The Battle of Christmas Island was over. The Japanese invasion was unopposed on land as the small garrison made up of mostly Indian soldiers surrendered almost immediately. A U.S. Navy communiqué issued on April 4, 1942, told of an American submarine sinking a Japanese light cruiser near the island and most likely sending a second one to the bottom.

Although hit by only one torpedo, the flagship Naka sustained serious damage. She was towed by the Natori back to Java before proceeding under her own power to Singapore for temporary repairs. The light cruiser eventually traveled back to Japan for permanent repairs before returning to the war zone in 1943, only to be sunk by American carrier-based aircraft near Truk on February 18, 1944. Although he survived Seawolf’s attack on Naka, Admiral Nishimura would die during the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

The fact that a larger score eluded Fred Warder and his men off Christmas Island was not due to a lack of daring leadership and hard work. Perhaps a victim of faulty torpedoes—a chronic problem during the early years of the war—Warder went on to complete seven war patrols with the Seawolf before being sent to command the U.S. Navy’s submarine school in New London, Connecticut. He earned the reputation of being a skilled and courageous submariner. Postwar records credit him with sinking six Japanese warships. He eventually attained the rank of admiral.

Seawolf was not so lucky. She completed 14 war patrols, sinking 27 and damaging 13 enemy ships, accounting for a total of 108,600 tons sunk and 69,600 tons of ships damaged. But, on September 21, 1944, with Lt. Cmdr. A.L. Bontier in command, she left Brisbane, Australia, on her 15th war patrol, making a brief stop at Manus Island to pick up supplies and Army personnel for delivery to Samar. On October 3, Seawolf exchanged signals with the submarine Narwhal and was never heard from again.

It is probable that Seawolf was mistakenly sunk near Morotai Island on October 3 by an American destroyer escort and aircraft that were hunting for a Japanese submarine thought to be in the area. The entire crew of 79, and the 17 Army personnel, were lost with the boat.

As the Navy’s Silent Service tribute says, Seawolf “remains at sea on eternal patrol.” The heroism of the brave men who served aboard her—and the more than 3,300 submariners who perished during the war—is untarnished by the passage of time. n

Ned Beach writes about Seawolf’s struggles in the early days of the Pacific in his interesting memoir “Submarine,” which started off as a series of articles for “The Saturday Evening Post.” An entire chapter is devoted to it.

It was the first personal memoir of the US submarine war, written shortly after V-J Day, and it directly brought home the terrifying realities and the good humor of the American submarine war. Decades it still stands up as fine history, writing, and reportage.

MAPS??? I much prefer maps to photographs. Please.