By Steven L. Ossad

For more than 45 years, Joseph Mansfield prepared himself for the ultimate test of a soldier—high command in time of war. After a long and successful career marked by bravery in the field and rapid promotion during the Mexican War, celebrated achievements as a military engineer, and a distinguished tenure as inspector general of the U.S. Army, the moment he had waited for all his life arrived early on the morning of September 17, 1862, near Sharpsburg, Md.

A Military Engineer in the Northern Army

Mansfield, a descendant of the first English colonists and the youngest of five children, was born to Henry Mansfield, a prosperous Connecticut East Indies trader, and his wife, Mary Fenno Mansfield, at New Haven, Conn., on December 22, 1803. Just months after his birth, his mother was granted a divorce on grounds of adultery after she discovered her husband openly living with a woman in St. Croix, Virgin Islands. Soon afterward, the family moved to Middletown so that Mary could be close to her family.

Lieutenant Colonel Jared Mansfield, an uncle and professor at the new military academy at West Point, began lobbying for young Joseph’s admission, writing frequently to President James Monroe and Secretary of War John C. Calhoun. In 1817, still shy of his 14th birthday, Joseph was accepted to the academy, the youngest member of his class and one of the youngest ever admitted to West Point. Graduating second out of 40 in the class of 1822, he was commissioned in the prestigious Army Corps of Engineers just before his 19th birthday.

With America planning long-term defenses in order to give teeth to the Monroe Doctrine, such a commission was a dream assignment for the bright young engineer. Mansfield spent the next quarter-century as a military engineer, mostly building coastal fortifications along the South Atlantic and Gulf coasts. He met his greatest challenge in 1830 when he was dispatched to Georgia to take over the construction of Fort Pulaski. A massive, five-sided stone edifice with mounts for 150 cannon, the fort was built on Cockspur Island at the mouth of the Savannah River to protect the city of Savannah from naval attack. One of the first junior officers assigned to Mansfield’s command was another recent West Point honors graduate, 2nd Lt. Robert E. Lee, who was responsible for preliminary site development and design. For more than 14 years, Mansfield supervised the major construction project.

Thanks to his familiarity with the Texas coast as a result of his frequent expeditions to locate suitable supply depot locations, Mansfield was appointed head engineer of General Zachary Taylor’s Northern Army at the outbreak of the Mexican War in 1846. Accompanying Taylor on the march across the disputed territory between the Nueces and Rio Grande Rivers, Mansfield’s first major assignment was the construction of Fort Texas (later renamed Fort Brown), a star-shaped, earthen fort opposite Matamoras, near present-day Brownsville, built to anchor the American position on the Rio Grande.

Defending Fort Texas

Several weeks after the opening skirmishes of the war, Taylor marched his main force to the coast to secure his supply lines, leaving behind several officers, including Mansfield, and 500 men to defend the fort. Mexican gunners opened their assault on May 3, 1846, and for six days kept the fort under siege and artillery fire. With no relief in sight, the Americans boldly took the offensive. Mansfield led a band of soldiers out of the fort and blew up Mexican fortifications, bolstering morale. Taylor’s subsequent victories at Resaca de la Palma and Palo Alto forced a Mexican withdrawal. Mansfield was brevetted major for “gallantry and distinctive service” in defending the fort. He was not modest about his achievements, observing in a letter to his wife, Louisa, that General Taylor owed his success “more to my opinions before the battles of Palo Alto & Resaca than to any other circumstances.”

That September, during the approach to the city of Monterrey, Taylor’s army came under artillery fire that halted their advance. Mansfield, accompanied by a squadron of dragoons and a company of Texans, led a small group of engineers forward to conduct a reconnaissance of the Mexican defenses. Such assignments were typical for the engineers of the time, whose training, drafting, and map-making skills made them invaluable to their commanders for conducting intelligence and planning missions. Mansfield’s field observations were crucial to the final attack plan, and on September 23, 1846, he personally led a column of volunteers, with a sword in one hand and a spyglass in the other. Seriously wounded in the leg, he was brevetted to lieutenant colonel for “gallant and meritorious conduct.” Visited daily by Taylor during his five-month convalescence, Mansfield recovered sufficiently to act as an adviser during the Battle of Buena Vista on February 23, 1847. He was brevetted yet again, this time to colonel, becoming one of a very few officers who received three brevets during the war, a list that included Robert E. Lee, George McClellan, and Joseph Hooker.

In spite of his record, however, Mansfield remained a captain in the engineers, the result of reductions in the Army and a glacially slow system of advancement. On May 28, 1853, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, impressed by Mansfield’s work on the board of engineers and a witness to Mansfield’s courage in Mexico, promoted the 50-year-old captain to colonel and inspector general of the Army, with responsibility for the vast territory west of the Mississippi. It was a rare instance of an officer jumping several ranks in contravention of the normal seniority rules. General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, Taylor’s rival during the Mexican War, opposed the move, viewing Mansfield as a “Davis man,” but the new inspector general proved to be both effective and independent in his duties.

For the next eight years, Mansfield was one of the most traveled men in the country. He toured the New Mexico Territory, the Division of the Pacific, the Departments of Texas, Utah, California, and Oregon, and finally returned to Texas, where he remained until that state voted for secession. After a danger-filled journey back to the capital, Mansfield was placed in command of the Department of Washington on April 27, 1861, and three weeks later he was named one of the first of the newly authorized brigadier generals in the Regular Army.

Constructing Washington’s Defenses

With responsibility for the defense of Washington and its environs, Mansfield put his vast expertise on defensive fortifications to work, supervising the planning and construction of the entire system of earthwork installations that protected the capital throughout the Civil War. One of his most important decisions was to seize and fortify the southern bank of the Potomac, especially Arlington Heights, without waiting for orders and over General Scott’s objections.

In August 1861, Mansfield was assigned to the Department of Virginia, first commanding a brigade at Norfolk, then a division at Suffolk. It was essentially occupation duty, boring and routine, except for one dramatic moment. While on duty at Newport News, Va., on March 8, 1862, Mansfield witnessed one of the great moments in naval history when the ironclad CSS Virginia (better-known as the Merrimack) savaged the Union fleet, sinking the USS Cumberland and capturing the USS Congress. Personally directing the shore batteries and the riflemen of the 20th Indiana Volunteers, Mansfield ran between the exposed positions with his white head bared, inspiring his men and helping to rescue Cumberland’s survivors. The encounter was not without some risk, as Mansfield described in a letter to his wife: “I came very near being killed again. I had just dismounted & stepped into my room to write a telegram to Genl Wool when a large shell from the Merrimac went through smashing everything before it & knocking down my chimney & stopped just behind my chair as I was writing. Fortunately it did not burst & I was saved again.”

A New Commands, a Premonition of Disaster

Mansfield was serving as military governor of Norfolk when Maj. Gen. George McClellan selected him to command XII Corps, formerly Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Bank’s II Corps in the Army of Virginia, in the aftermath of Maj. Gen. John Pope’s defeat at Second Bull Run. Mansfield was seized with a premonition of impending disaster. At the close of a visit with Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, an old friend from Connecticut, he took his leave, declaring, “We shall probably never meet again.” Just hours before departing Washington on September 13, 1862, Mansfield penned a brief note to his old West Point teacher Sylvanus Thayer “to say that if I never see you again, that I have not forgotten your inestimable favors to me.”

Arriving on the eve of what everyone expected would be a great battle, Mansfield was completely unacquainted with his hastily assembled staff. In the two days that preceded the battle, he did not impress the officers in his corps. Although well aware of his reputation and struck by Mansfield’s distinguished physical appearance, senior division commander Brig. Gen. Alpheus S. Williams described him in a letter to his daughters as “a most veteran-looking officer, with head as white as snow,” but also as “a most fussy, obstinate officer.” Mansfield, for his part, seemed overwhelmed by his responsibilities, and perhaps in compensation intervened often in the movement and deployment of brigades, regiments, and batteries, bypassing the chain of command and causing even more than the normal confusion in the ranks.

The ordinary soldiers of the corps, however, had a distinctly positive reaction to their new commander, whose genuine enthusiasm and warm personality outweighed his apparent inexperience in leading combat troops. Hit hard during the Second Bull Run campaign, the men needed all the encouragement they could get. Williams’s 1st Division had lost nearly all its field officers, and its ranks were so reduced that several of the old regiments mustered only 100 men. Five new regiments had been added, all green and barely three weeks away from home. In the rapid marches from Frederick, Md., many had been lost to straggling and desertion. Altogether, XII Corps numbered 12,300 soldiers, including noncombatants, and contained 22 regiments of infantry and three batteries of light artillery. It was the smallest corps in the Army of the Potomac.

The Battle of Antietam

After receiving orders just after midnight on September 17 to support Hooker in his dawn attack, Mansfield’s men crossed Antietam Creek via the upper bridge at 2 am and bivouacked on the Hoffman and Line farms, about a mile behind Hooker’s left. Because of the nearness of the enemy, the men were ordered to lie down with their arms; but few were able to sleep, including the commander. Mansfield moved constantly among his troops, waking Williams several times with new directions before finally spreading his blanket near a fence corner close to the Line house, where he was able to get a few hours of fitful sleep.

At the first explosion of cannon fire at daybreak, Mansfield led his corps toward the sounds of battle without waiting for food or coffee. He had no idea what his mission was—general support of Hooker, exploitation of a breakthrough, or defense against a possible Confederate counterattack. McClellan had issued no specific instructions. From the moment they started to move, his men were under fire from four batteries of Confederate artillery sited on the plateau opposite the Dunker Church. Slowed by the cannon fire, the advance was even more confused because of Mansfield’s frequent pauses for unit detachments and reattachments, although none of the halts was long enough to allow the men to boil their much-needed coffee.

Reflecting attitudes developed over a lifetime in the Regular Army, Mansfield had little confidence in the volunteers and ordered his men deployed in “column of regiments in mass.” In such a formation, regiments were deployed 10 ranks deep, instead of two ranks as in the conventional line of battle. Williams’s division was on the right and Greene’s was on the left, with the line extending from farmer David R. Miller’s house on the Hagerstown Pike southeast across the Smoketown Road.

From the first, Mansfield seemed to be everywhere, riding up and down the line, shouting encouragement to his men and generally behaving like a junior commander whose blood was up. While at first he appeared to the men as “a calm and dignified old gentleman,” he soon seemed “the personification of vigor, dash and enthusiasm,” riding “with a proud, martial air and full of military ardor.” By 6:30 am, the head of his lead column had reached the middle of an open field west of John Poffenberger’s woods, and Mansfield rode forward to personally reconnoiter the ground. Williams then ordered Brig. Gen. Samuel W. Crawford’s brigade of regulars and green Pennsylvania men to abandon the massed formation and deploy into line of battle. At the same time, Mansfield was informed that I Corps was hard pressed and needed immediate help.

Riding back to his command, Mansfield saw Crawford’s men maneuvering and immediately ordered Williams to halt the deployment. Even though the men were still under intense artillery fire, he ordered them again to mass in dense columns. Williams protested, but Mansfield refused to allow the men to spread out in the open field, repeating once again his concerns that if the green volunteers were deployed in line they would be impossible to control and might break and run.

Mansfield planned to move his corps via the Smoketown Road to the northwest corner of the Cornfield and into the East Woods and renew the attack against the left of the Confederate line held by Maj. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. The earlier attack by Hooker’s I Corps had nearly broken through, dissolving only after terrible losses. Another push might crack the weakened enemy line, and the old soldier was determined to make the attempt at the head of his corps. Ignoring his staff, Mansfield personally guided the veteran 10th Maine Volunteers to its position in the van of Crawford’s brigade as it entered the East Woods. He then turned back to guide the green 128th Pennsylvania to the field.

A Mortal Wound

Astride his horse on a knoll just behind the front line, Mansfield paused with a group of officers and watched the rest of Crawford’s brigade move into position. As soon as his men opened fire, however, Mansfield spurred his mount and rode up to the front rank of the 10th Maine. Fearing that they were shooting at Hooker’s men retreating through the East Woods from the carnage of the Cornfield, he started screaming, “Stop, you are firing into our own men!” The Maine veterans, whose colonel had just been felled by Rebel sharpshooters, insisted that the men to their front were the enemy.

Sergeant E.J. Libby and Private Thomas Waite, standing close by, told Mansfield that “we were not firing at our own men for those that were firing at us from behind the trees had been firing at us from the first.” Other members of Company K also pointed out that the men facing them—veterans of the 21st Georgia and 4th Alabama Regiments—were dressed in gray and were even then aiming their rifles at them. Finally convinced that he had erred, Mansfield said, “Yes, yes, you are right,” and almost immediately was struck in the chest by a bullet. His head drooped and his body sagged against the saddle, but he was able to guide the stricken horse along the Hagerstown Pike toward the rear. At first no one knew that the general had been wounded. Then the wind blew open his coat, revealing his blood-soaked shirt. At this point some soldiers helped Mansfield dismount and took him to the rear. The lines of battle rolled forward and the attack of XII Corps proved to be just one more futile effort to force the Confederate line.

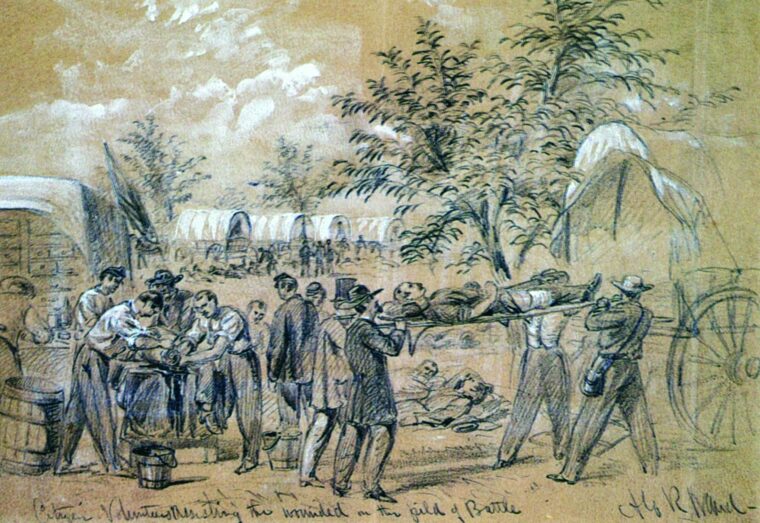

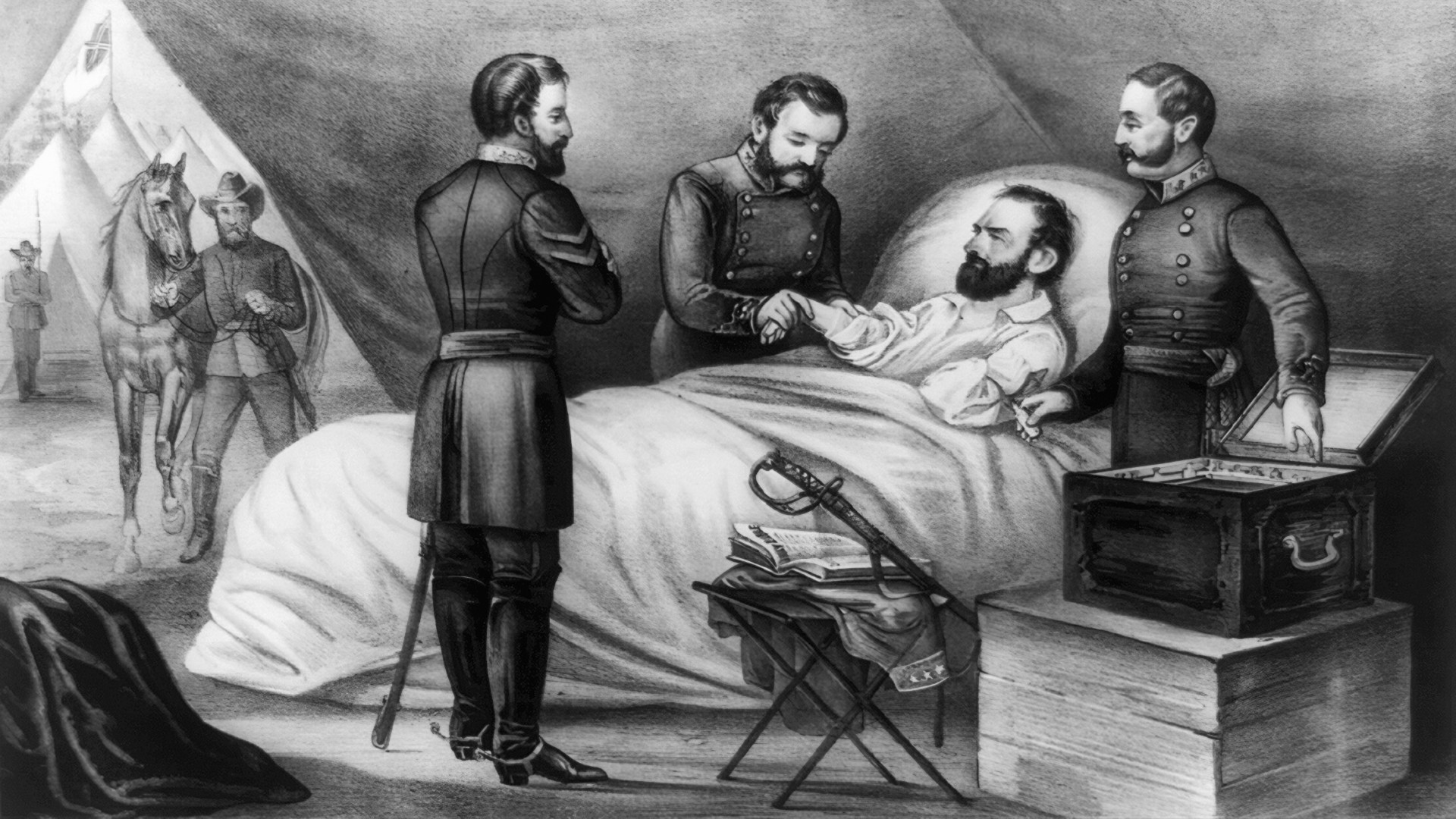

Mansfield was taken in an ambulance to the makeshift hospital at Line’s house less than a mile away. There he was attended throughout the next 24 hours by a team of three surgeons, as well as Captain Clarence H. Dyer, his faithful aide-de-camp, who stayed at his side throughout the ordeal. Drifting in and out of consciousness, alternately asking after the well-being of his comrades and uttering words of prayer, Mansfield gradually weakened and died just a few minutes after 8 on the morning of September 18.

Mansfield’s moment of glory had lasted less than a half-hour. All around the spot where he fell were the mortal remains of his shattered corps. At least 275 men lay dead and another 1,470 wounded were crowded into the small area around the East Woods, a casualty rate of nearly 20 percent of those engaged. Posthumously confirmed as a major general of volunteers, Mansfield was the longest serving soldier on the field that day and the highest ranking casualty of the Battle of Antietam. He was also the oldest graduate of West Point, as well as the oldest general, to be killed in battle during the Civil War. He died at his post, with his face turned toward the enemy—a fitting epitaph for any soldier, no matter how long the service or brief the glory.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments