By Robert Collins-Suhr

With its whistle blaring, the Confederate gunboat Grampus steamed into Madrid Bend, where Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Arkansas come together on the Mississippi River. Within days the reason for this excitement became evident as six ugly ironclad gunboats anchored a few miles upriver near Island No. 8. The Union Navy’s long anticipated attack down the river had begun.

The Confederacy’s highwater mark on the Mississippi came at Columbus, Ky. On September 4, 1861, Gen. Leonidas Polk violated the Bluegrass State’s self-proclaimed neutrality by seizing the heights at Columbus and—farther downstream—Hickman on Kentucky soil just north of the Tennessee border. That tactical success was followed by an immediate strategic defeat as Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant seized Paducah and Smithland, at the mouths of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, advancing the Union front line from the Ohio River to the Tennessee border.

Attacking New Madrid & A Massive Earthquake

Still, the proximity of Confederate forces at Columbus to the large Union depot at Cairo, Ill., was a constant worry to Union commanders, forcing them to maintain a large garrison there. On January 20, 1862, Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, commander of the Military Department of Missouri, suggested to his superior, Maj. Gen. George McClellan, that he attack New Madrid, 30 miles downriver from Columbus. Such a move would trap the Confederate garrison, relieve the pressure on Cairo, and allow Halleck to use the Cairo garrison’s troops elsewhere.

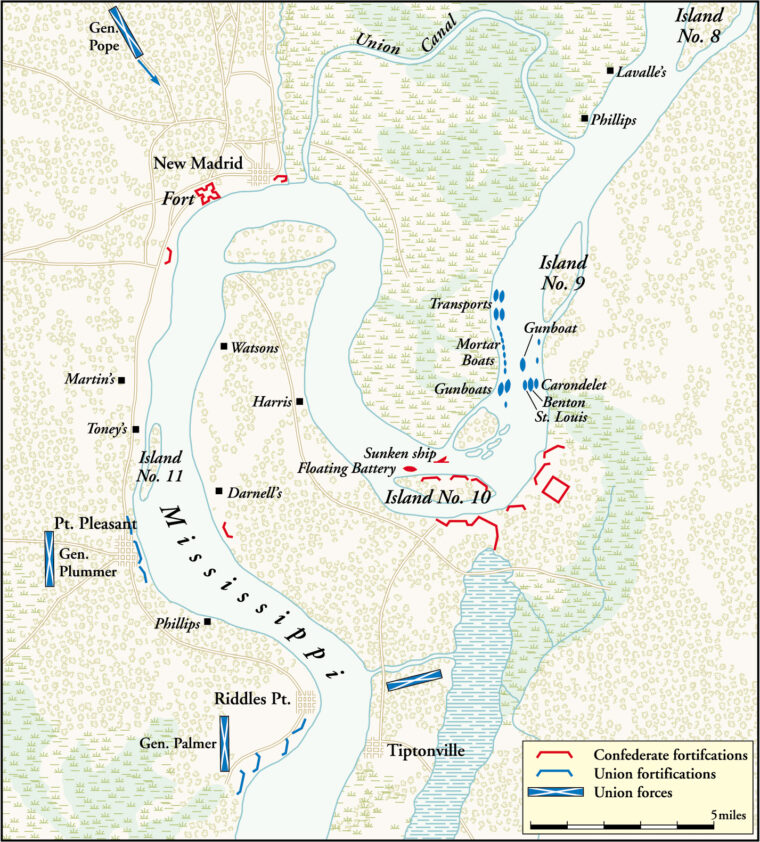

In 1811, a massive earthquake centered at New Madrid altered the geography of the area, giving the area unique terrain characteristics that would make it a logical defensive position. At Madrid Bend, the Mississippi River twisted back and forth in a pair of serpentine curves. In the first bend was Island No. 10, so named because it was the tenth island south of where the Ohio flows into the Mississippi. The town of New Madrid was in the second bend. Island No. 10 and its environs onshore would be a natural stronghold and barrier to Union shipping from the north.

The Anchor of the Confederate Right

Reelfoot Lake in Tennessee anchored the Confederate right; a swamp between it and the river made it impossible for any force to advance from that direction. The Great Mingo Swamp in Missouri formed a 30-mile-wide barrier north of New Madrid. At Madrid Bend, the western peninsula made by the two river bends and jutting up from Tennessee toward New Madrid, was another swamp that protected the Confederate left in Tennessee. Moreover, heavy rains during late winter flooded the Mississippi. The water in the swamps was several feet higher than normal, making them even more difficult to pass through.

When the Confederates eventually abandoned Columbus in late February, the position being made untenable by Grant’s moves deep into Tennessee, they brought many guns that added to the area’s natural defenses. Eventually, 45 cannons were in batteries on the Tennessee shore, on Island No. 10, and in forts protecting New Madrid. To force enemy boats to steam close to the island, they sank the steamer Winchester in a channel opposite.

Floating Confederate Batteries

Another part of the Confederate defenses at Island No. 10 was a unique weapon of the war, the floating battery New Orleans. Originally the Pelican dry dock in Algiers (on the Mississippi opposite New Orleans), the floating battery resembled an immobile boat with cannon on both sides. When it arrived at Island No. 10, the Confederates removed the cannon from the starboard side and anchored it on the upriver end of the island with the port guns pointed north. To protect New Madrid, the Confederates erected a pair of forts on either side—Fort Bankhead upriver, and Fort Thompson downriver from the town.

The Confederates believed the Union attack on New Orleans would come from the north, where they had heard about construction of the Union ironclads. Commanding the Confederate naval force at New Orleans was Commodore George Hollins. When Union ironclads began operating on the western rivers, Richmond ordered Hollins to take most of his fleet north to help defend the Mississippi.

The Fatal Flaw in Confederate Defenses

Thus, the Confederates had a number of boats at Madrid Bend, but they were gunboats in name alone. In reality, they were nothing more than steamers with cannon mounted on them. The most heavily armed was the McRae with eight guns. The ships were unarmored except for the Maurapas, which had iron plating over its engines. The fatal flaw in the Confederate defenses was that they were all geared toward a naval attack coming downriver.

At this time, the Union’s Western Flotilla was under army command. Though Halleck could order Flag Officer Andrew Foote to support any operation he wished, he had committed the gunboats to helping Grant reduce Fort Henry and Fort Donelson on the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. To attack Island No. 10 and New Madrid, Halleck had only infantry.

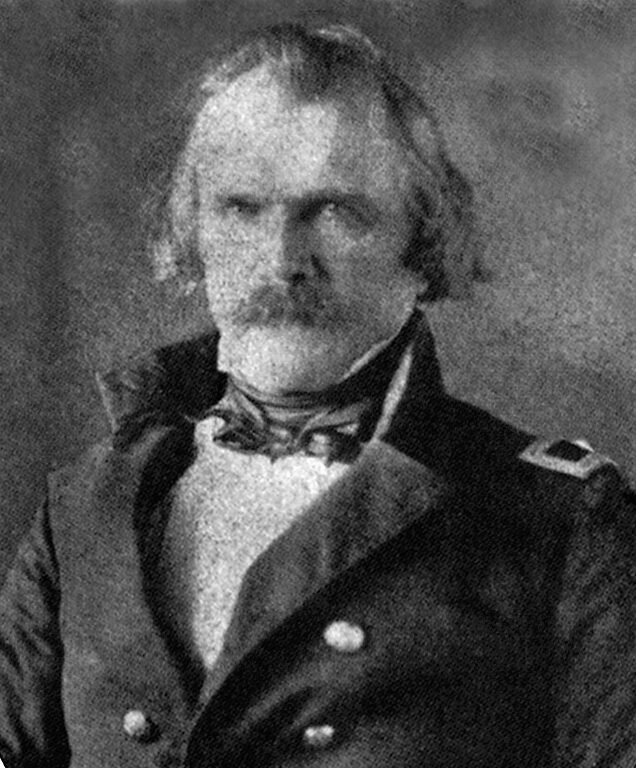

Brig. Gen. John Pope

By mid-February, McClellan had given Halleck permission to begin the operation. Halleck chose Brig. Gen. John Pope to command. Pope was at Jefferson City, Mo., on February 14 when he received Halleck’s orders. He immediately traveled to St. Louis to meet with Halleck, who promised him all the support he needed. From there he went to Cairo and established his headquarters.

While there, Pope heard rumors that the Confederates were about to attack Cairo from Columbus. Halleck ordered Pope to remain in Cairo as long as there was the risk of a Confederate assault.

Moving His Headquarters Up the Mississippi

By February 21, Pope, deciding the Southerners were not going over to the offensive, moved his headquarters 30 miles up the Mississippi to Commerce, Mo. This put the Union Army on the same side of the Mississippi as New Madrid, at the end of an old corduroy road that ran through the swamp.

The force Pope commanded could hardly be called an army. His original force was the 140 men of his personal escort. The units assigned to him were green and untrained, many not receiving their arms until they were about to cross the river. In three days he was able to report to Halleck: “There are now here nine regiments of infantry, one battery Eleventh Ohio, and six companies of the First U.S. Infantry, about 6,500 men.” Within days he had 10,000 men.

“The Union Army at New Madrid”

With the arrival of Brigadier Generals David Stanley, Schuyler Hamilton, John Palmer, and Gordon Granger, Pope organized his force into four divisions. A week after his arrival, Pope was ready to move south at the head of the force that would later be named the “Army of the Mississippi,” but at that time was simply referred to as “the Union Army at New Madrid.”

On the last day of February 1862, two weeks after Grant took Fort Donelson, Pope set out for New Madrid, 30 miles south. As if Pope did not have enough problems, it began to snow, and measles struck the army.

The Confederate belief that the swamp would protect the area from the north was not unfounded, even with the presence of the old track through it. The corduroy road was built on a crumbling embankment that had collapsed in several places. To make the road passable again, men had to wade into the freezing water to build supports.

Pope’s intentions were known to the Confederates almost as soon as he landed at Commerce. As he started south, Confederate Brig. Gen. M. Jeff Thompson, “The Swamp Fox,” rode north from New Madrid to stop him. Though Thompson had been a thorn in the side of Union forces for months, he could only muster fewer than 100 soldiers and two or three small cannon to stop Pope’s 10,000 men.

At two o’clock on the morning of March 1, elements of the 1st Illinois Cavalry and the 10th Illinois Infantry encountered Thompson’s force on dry ground three miles south of Sikeston, Mo. Pope ordered Hamilton to send forward the 7th Illinois Cavalry under Col. W. P. Kellogg. Without taking time to change from a column to a line, Kellogg led a charge that routed the Rebels, capturing a couple of officers and several privates. Kellogg’s troopers continued the chase to within four miles of New Madrid.

Halleck’s vague plan of cutting off the Confederate garrison at Columbus (one of the original reasons for marching on New Madrid) came to naught because of Union successes to the east. Grant’s position at Fort Donelson was due east of Columbus, and the movement of his Army of the Ohio toward Nashville placed a large Union force between Columbus and the army General Albert Sidney Johnston was assembling to protect the important rail crossing of Corinth, Miss. Afraid that Grant would come west to cut off the forces at Columbus and Hickman, General P. T. Beauregard, who commanded the Army of Mississippi under Johnston, ordered Leonidas Polk, commanding his First Grand Division, to evacuate Columbus.

After Forts Henry and Donelson, the Union Army’s objective in early 1862 was Corinth, where the east-west Memphis & Charleston Railroad crossed the north-south Mobile and Ohio. The loss of Corinth would sever supply lines east-west, forcing the Confederacy to abandon the Mississippi as far south as Vicksburg. Union gunboats were already steaming up and down the Cumberland and Tennessee, and Grant’s army was about to move to Pittsburg Landing, only 30 miles northwest of Corinth. To repel the northern invaders, Johnston drew troops from all over the Confederacy. Johnston’s plans would result in the Battle of Shiloh on April 6-7.

As part of the concentration of forces, Beauregard sent the bulk of the troops from Columbus to Union Junction, Tenn., to join Johnston. Only one brigade moved to the area of Island No. 10.

On February 24, Polk had sent Brig. Gen. John McCown to Island No. 10. What he found there was less than encouraging. While Columbus was considered the “Gibraltar of the West,” the area about Island No. 10 had only two incomplete batteries. McCown immediately ordered the construction of several more.

Polk began evacuating Columbus on February 25, sending his sick out first. During the remaining few days of February, he moved the commissary and quartermaster supplies and almost all the heavy guns south. By March 1, only cavalry remained in the fort.

On March 3, the Union army reached New Madrid. Though he did not admit it, Pope arrived outside the little town with no plan for capturing it and the Confederate forts. Moreover, the Confederate gunboats rode so high on the flooded Mississippi that their cannon could sweep the flat countryside. Union troops could not deploy to properly invest the Confederate position without being battered by fire from the gunboats.

The first day, Pope was content to probe the Confederate position. He concluded that five regiments held the forts about the town and that the environs could be swept by 60 large guns in the forts and on the boats. He bivouacked the army at the end of the swamp, beyond the range of the Confederate cannon.

Instead of attacking, Pope decided instead to blow the Confederates from their positions using siege guns. He sent Col. Josiah W. Bissell of the Engineer Regiment of the West to St. Louis to ask Halleck for some heavy artillery. “If we can get them here matters will soon be settled.” On March 10, the ordnance officer at Cairo turned over three 24-pounders and an eight-inch rifle to Bissell. Meanwhile, Pope’s little army continued to grow as Halleck added new regiments. Colonel H.E. Paine arrived with an additional five regiments. Pope created a fifth infantry division under Paine’s command and put Granger in charge of a cavalry division.

While waiting for the siege guns, Pope conducted a series of reconnaissance-in-force probes of the Confederate defenses. He hoped to lure the Rebels out of their works to fight in the open where his superior numbers could prevail, but the Confederates refused the bait.

Still awaiting the large guns, Pope then ordered Colonel Joseph B. Plummer’s brigade to the river town of Point Pleasant, six miles south of New Madrid. Plummer planned to take the town at dusk so that by dawn his position would be fortified. The direct road to Point Pleasant, however, lay along the river where the Confederate gunboats could pummel the Union column with harassing and interdicting fire. To avoid this, Plummer’s men had to march a circuitous route 14 miles long to reach the town. As a result, the troops were still three to four miles from their objective at dusk and too tired to continue. Plummer chose to bivouac where he was and wait for dawn.

The Union infantry advance on Point Pleasant the next morning caught the steamer Mary Keene tied up at the riverbank. Union troops moved into the town while infantry and artillery fire peppered the boat until it finally managed to escape. This arrival of Union troops in the Confederate rear drew the gunboats to the town. Plummer pulled his cavalry and artillery from town at their approach. The infantry stayed despite the scream of gunboat shells hitting the town.

On March 7, Plummer put a battery on the riverbank. Both Union batteries and Confederate gunboats fired away at each other during the day without success, but the presence of the battery at the river’s edge forced the Confederate boats to hug the eastern riverbank going up and down the river.

When he knew the siege guns were on the way, Pope ordered Maj. Warren L. Lothrop, his artillery commander, to find a suitable position for them. On the 11th, accompanied by Captain Louis Marshall of the 1st U.S. Infantry and a squadron of dragoons, Lothrop moved within half a mile of the forts. He reported: “From this position (northwest of the town) I could see distinctly their gunboats and lower fort. I determined at once, from my observation, where to plant the battery.” The next day Marshall and Bissell confirmed this was the best position.

Lothrop returned at dusk with Colonel James Morgan’s brigade, consisting of the 10th and 16th Illinois Infantry. One regiment formed a skirmish line 50 yards in advance, while the other dug the emplacements for the batteries.

Although Pope lacked artillerymen to handle the heavy guns, he did have Capt. Joseph A. Mower with the 1st U.S. Infantry. During the night, two companies of the 1st Infantry brought up the heavy guns. Mower, with Company H, emplaced one 24-pounder and the eight-inch rifle in Battery No. 1 on the left facing Fort Bankhead. Lt. Charles Fletcher commanded Company A in Battery No. 2 with the other two 24-pounders facing Fort Thompson. In case of a sally by the defenders, Pope placed Brig. Gen. David S. Stanley’s division a short distance away to support the guns.

Because he had limited ammunition, Pope ordered Mower to concentrate his fire on the Confederate gunboats in hopes of driving them away. On March 15, Mower gave Pope his report of the bombardment: “I was ordered by General Stanley to open fire on the enemy at daylight on the 13th, which I did from both batteries. Our fire was briskly replied to by the fort, which was in front, and the gunboats, which took position both in front and towards our left flank. They threw rifled shot, shell, and round shot. At about 10 o’clock a.m. a round shot struck one of the guns in Battery No. 1, breaking a piece out of it, and killing one man and wounding six. In the afternoon the gunboats withdrew from our front, and taking position beyond the reach of our guns, kept up a steady fire, with occasional intermissions, until sundown.”

During the day, the Union men continued to dig trenches, gradually moving closer to the Confederate works. Pope hoped during the night to move the batteries closer to the forts. A heavy thunderstorm that struck at 11 pm and continued throughout the night kept Mower from advancing the guns. To increase pressure on the Confederates, Pope sent Brig. Gen. Schuyler Hamilton’s division to replace Stanley’s division just before dawn.

Mower’s fire had driven back the Confederate gunboats. Without their support, McCown believed he could not hold the forts. During the thunderstorm, he sent gunboats and a steamer to the forts to remove the garrisons. One naval officer would later write: “A darker and more disagreeable night it is hard to conceive; it rained in torrents, and our poor soldiers, covered with mud and drenched with rain, crowded on our gunboats, leaving behind provisions, camp equipments and artillery.”

As Mower prepared to resume the bombardment at dawn, he received an order from Hamilton to hold his fire; a man with a white flag was approaching. Mower took 20 men forward to determine if the Confederates had abandoned Fort Bankhead. Not having the colors of the 1st Infantry, Mower borrowed the regimental colors of another unit. “I proceeded to the fort and found that the enemy had deserted it. I raised the flag upon the ramparts and took possession of the works.”

An officer in the 5th Iowa remembered: “The enemy had left in awful haste. I recall finding a dead Rebel officer, lying on a table in his tent, in full uniform. He had been killed by one of our shells. A candle burned beside him, and his cold hands closed on a pencil note that said, ‘Kindly bury this unfortunate officer.’ His breakfast waited on a table in the tent, showing how unexpected was his taking off.” Without a major fight, Pope had broken the back of the Confederate defenses.

Beauregard supported McCown’s action of abandoning New Madrid. With the situation deteriorating at Madrid Bend, Col. Thomas Jordan, Beauregard’s assistant adjutant general, sent a message to McCown describing the area as the “Thermopylae of the Mississippi.” Almost immediately Beauregard had second thoughts about McCown’s ability to hold Island No. 10. He ordered him to take most of the troops to Fort Pillow further downriver on the Mississippi. When McCown returned to Tiptonville, he discovered Beauregard had replaced him with Brig. Gen. W. W. Mackall.

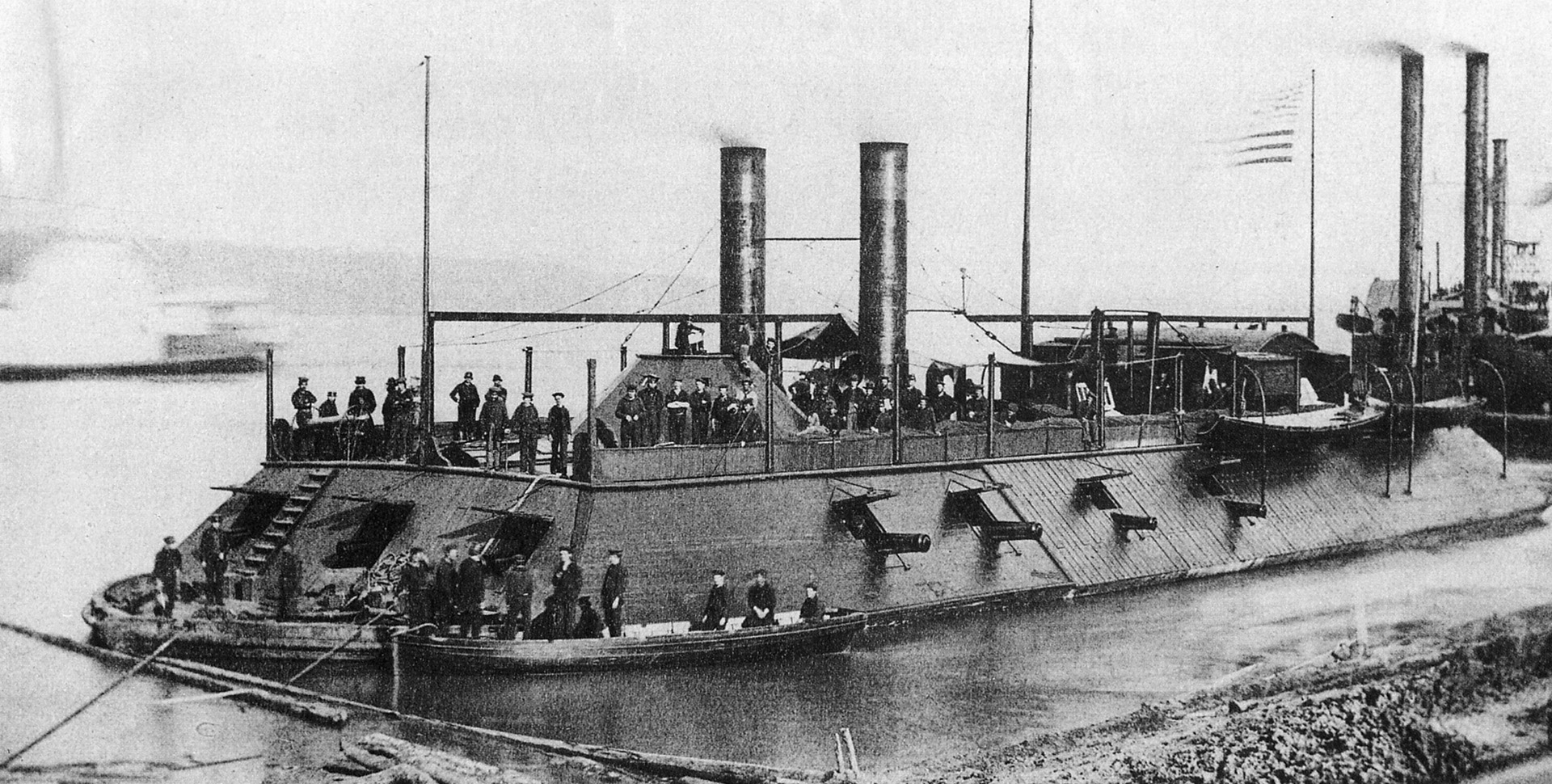

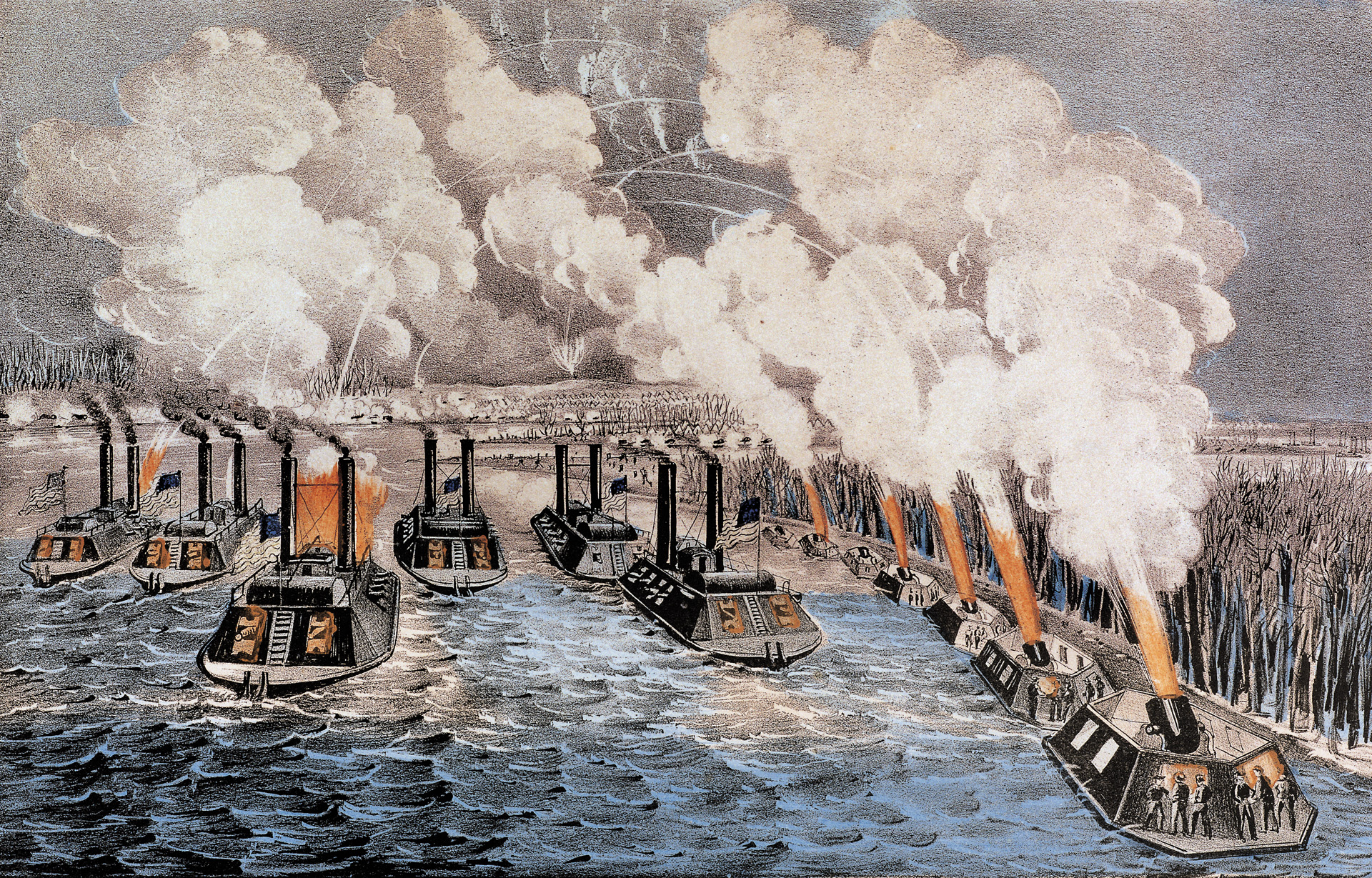

It was not until the next day that the Union Western Flotilla finally arrived upriver from Island No. 10. The backbone of the Western Flotilla at this time comprised the seven ironclad gunboats named for river towns. Built in Carondelet, Mo., they were nicknamed “Eads Ironclads” after their builder, James Eads, or “Pook Turtles,” for Samuel M. Pook, the naval constructor.

The ironclads were 175-feet long with a beam of 51.5 feet. Drawing only six feet of water, they were designed to steam at nine miles per hour. The boats were underpowered and in the flooded Mississippi had trouble moving against the current.

With little room to maneuver in the river, they became floating gun platforms rather than warships. Each carried three 9- or 10-inch bow guns, four 32-pounders on each side, and two light guns on the stern. Although the gunports were only a foot above waterline, the gunners could not elevate the guns.

What made “Eads Ironclads” unique (and unmanageable) was the iron plating. An oak casemate covered the topsides, with 2.5 inches of iron plate on top of that. The casemate was sloped 35 degrees to deflect cannonballs. The flagship of the flotilla was the Benton, a former snag-boat converted to an armored gunboat. The Benton had even less power than the other ironclads and could barely make progress against the current. Nevertheless, they were effective. These ironclads were first used at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson. Though the Confederates held out longer than the ironclad sailors had hoped, naval gunfire forced Fort Henry to surrender before Grant had his army in position to attack.

It was a different story at Fort Donelson. Twenty years later, writing for Century Magazine, Henry Walke described what happened as cannonfire pounded the Carondelet. “Another ripped up the iron plating and glanced over; another [roundshot] went through the plating and lodged in the heavy casemate … and still they came, harder and faster, taking flag-staffs and smoke-stocks, and tearing off the side armor as lightning tears the bark from a tree.” During the bombardment, the Carondelet was struck 54 times.

The situation at Island No. 10 put Foote in a quandary. If the army had Corinth as its objective, the Navy’s objective was to reach Memphis before the Confederates could finish their ironclad rams Arkansas and Tennessee. Though he had to move downriver quickly, Foote knew he could not afford to have one of his ironclads disabled. Being upriver from the Confederates, a boat without power could drift down into their hands and, once repaired, could then be used against its former owners.

On the 13th, Foote wrote the Navy Department of the problems in using the ironclads to bombard the Confederate defenses. He told them that when anchored so the armored bow pointed toward the enemy’s guns, the river current flowing against the hull caused the boats to weave, making accurate aim impossible. The alternative was to expose the unprotected sterns to enemy fire. Foote concluded the primary bombardment would come from the mortarboats, with the gunboats offering what support they could.

Foote decided days before to limit the use of his ironclads and to concentrate the naval bombardment with the mortarboats. These ungainly craft were the brainchild of Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont, created during his short tenure as commander of the Department of the West. They were little more than wood rafts upon which were mounted 13-inch siege mortars.

On March 17, the Navy began a 19-day bombardment of the Confederate defenses. Along the eastern riverbank, the Benton was lashed between the Cincinnati and St. Louis with the Pittsburgh joining them. The Mound City and Carondelet were on the west bank. Beginning at 1:20 pm, each boat fired one round per minute.

Though the Confederates struck the Benton several times, due to the long range none of the hits caused much damage. The Union Navy had no better results. They managed to dismount some guns in Battery No. 1, and at one point holed the New Orleans, which the Confederates let drift out of range so they could repair it. By April 4, the opposing forces were as strong as they had been on March 17.

Capt. Edward W. Rucker commanded Battery No. 1. At the onset of the firing, Captain A. Cummings established a signal station there because flooding had isolated the battery. Cummings selected as his signaling device a white flag. When Foote saw a white flag waving, he sent a tug downriver under a white flag to see if Rucker wanted to surrender. Rucker did not.

Later, a certain E. Jones took over signaling duties in Battery No. 1. The Union artillery shells landing about the guns sent tons of mud flying about, ripping the flag from his hands three times. Eventually Jones found himself without a staff, forcing him to hold the flag in his hands to signal the next station.

None of this was really doing the job. Pope was soon convinced the only way he could capture Island No. 10 was by crossing the Mississippi and cutting the road through Tiptonville that supplied the Confederates by land, the water supply route having already been severed by the presence of Union batteries near New Madrid. The southerners, anticipating such a cross-water attack, had erected batteries at every landing spot between Madrid Bend and Tiptonville. The Union Army needed troop transports to get the men across as well as some sort of gunboat to escort the transports and suppress enemy fire near the landing zone.

Trying to get Foote to run his gunboats past the defenses of Island No. 10, on March 20, Pope sent engineer Bissell by dugout canoe across country through the bayou to talk to him. Bissell expected to return to New Madrid with the gunboats. Foote held a council of war with his captains to discuss their options. In his own article for Century Magazine, Bissell wrote: “The officers, with one exception, were decidedly opposed to running the blockade, believing it would be certain destruction to all the vessels that should attempt it.” The officer who argued about trying it was Cmdr. Henry Walke of the Carondelet. Foote remarked, “When the object of running the blockade is adequate to the risk, I shall not hesitate to do it.”

The naval officers believed the army was ridiculing them. Indeed, when Pope asked what the Navy was doing, one of his officers was reported to have replied, “Oh! It is still bombarding the state of Tennessee at long range.”

The next day, Bissell explored the eastern bank with two tugs to insure the Confederates could not escape in that direction. He then examined the western bank to see if St. James Bayou, seven miles above Island No. 8, was linked to St. John’s Bayou.

On the morning of March 22, while waiting for his guide to return with the dugout, Bissell saw an opening through the flooded fields that turned out to be a wagon road. At Bissell’s request, the guide drew a map of the bayou. The two men then explored the area, arriving back at Pope’s headquarters about dark.

While Pope complained about Foote’s refusal to run past the Confederate defenses, Brig. Gen. Schuyler Hamilton suggested building a canal from above Island No. 10 to New Madrid to bypass the Confederate defenses. Bissell then produced his map and said he could get a channel cut and boats through in 14 days.

With the Navy not responding to his pleas, Pope planned his own “floating batteries” to provide covering fire. The plan was to put three heavy guns protected by four feet of timber on a barge. On each side would be barges with layers of water-tight barrels, cotton bales and cottonwood rails so that a shot had to pass through 20 feet of “armor” to reach the center barge. The barrels and cotton bales would be arranged so that even if a barge was hit and filled with water it would not sink Protecting the battery from boarders would be 80 sharpshooters. The barges were to be hauled through the canal to New Madrid. Transports for the troops could come through the canal as well, but not the gunboats, which had too deep a draft.

Pope had no shortage of volunteers to man these makeshift firing platforms. He intended to tow them across the river from New Madrid, at the tip of Madrid Bend, where the swamp kept the Confederates from erecting any batteries. The barges would drift down to the landing points where the men would throw out anchors and man the guns.

That night engineer Bissell met with some of his officers, Capt. William Tweeddale and Lt. Mahlon Randolph, to plan the operation. At daybreak on March 23, these two officers started north toward Cairo with 100 men to get equipment for the barges. They were to come down the Mississippi to join Bissell at Island No. 8. The other 600 men of the regiment soon followed them north.

When they returned to Island No. 8, Bissell found Tweeddale and Randolph had four sternwheel steamers, six coal barges, cannon, saws and two million board feet of lumber.

The swamp at this time had eight to ten feet of water in it, but was still much lower than the height of the water in the river. When the engineers cut the bank, the water poured so swiftly from the river into the swamp that the men had to let the steamers in gradually, using ropes to hold them back. Thus, water was plentiful and the Union troops had no trouble getting through the flooded cornfield. Bissell put a steamer with a powerful steam capstan in the lead. The other steamers followed with the barges behind. Tweeddale took charge of cutting the channel, while Randolph remained in the rear working to turn the barges into floating batteries.

Meanwhile, soldiers on small platforms cut down giant cottonwoods eight feet above the water. Another group secured lines to the cut timbers and used the steam capstan to pull them from the channel. Next, soldiers used giant curved crosscut saws to cut the high stumps four and one-half feet below the surface. Men on two barges—one on either side of a stump—manned a saw’s ends, always above water. But the lower curve of a saw was below water. The soldiers would touch the lowest part of the bend of the saw to a stump and then sweep the blade back and forth using ropes. Thus, each end of the saw was always above water for operation by the men, but the cutting teeth were below water cutting through a stump.

Once through the swamp, the Union soldiers no longer had to deal with the giant cottonwoods, but they did have to remove numerous snags and dead trees imbedded in the mud. They labored at this work for 19 days.

By March 27, Foote began to rethink his policy. Once the steamers were through the bayous, Pope would have the means to ferry troops cross the Mississippi. If Pope’s floating batteries worked, they would make the ironclads unnecessary. That night he summoned his captains on board the Benton to question them again. Once more, all but Walke thought trying to run past the Confederate batteries was suicidal. Foote asked Walke if he was willing to try it with the Carondelet and received another affirmative reply.

While all this was going on, Pope had been increasing pressure on the Confederate supply line by placing batteries along the western bank of the Mississippi at Point Pleasant and the point opposite Tiptonville. The Confederate gunboats, congregated at Tiptonville after their withdrawal from New Madrid, saw the batteries as a threat to the Confederate supply line. Lieutenant C. W. Read, the executive officer of the McRae, would later write, “Early one morning we perceived a number of men on the opposite side of the river from us, engaged in throwing down a large pile of wood that had been placed on the bank for the use of our transports. About the time Commodore Hollins had made up his mind to send over and ascertain who the party were, a puff of smoke was seen to rise near the men, and a shell came screaming across the river, striking the bank near us. Fortunately our boats had steam up. The signal was hoisted on the McRae to engage the battery at ‘close quarters.’”

The ensuing engagement revealed that Hollis shared Foote’s fears about ship-to-shore engagements. “The McRae fired away at long range, but soon perceiving a small yawlboat adrift (which had been cut from the Maurapas by a shell), we ceased firing, and went a mile below to pick up the boat. In the meantime the Polk had received a shot between wind and water, and signaled that she was leaking badly. The Yankees had left all their guns except one and were firing slowly and wildly, when the McRae signaled to ‘withdraw from action.’ So we all steamed down the river five or six miles and anchored.”

This skirmish tightened the screws on the Confederate defenders. Now the only way to get supplies to Island No. 10 was to send a gunboat up the river under the cover of darkness to Tiptonville, then be hauled overland by the Tiptonville Road.

By April 3, Bissell’s men were through the swamps. The men brought the steamers and barges to the mouth of the bayou, keeping them hidden while Randolph finished the floating batteries.

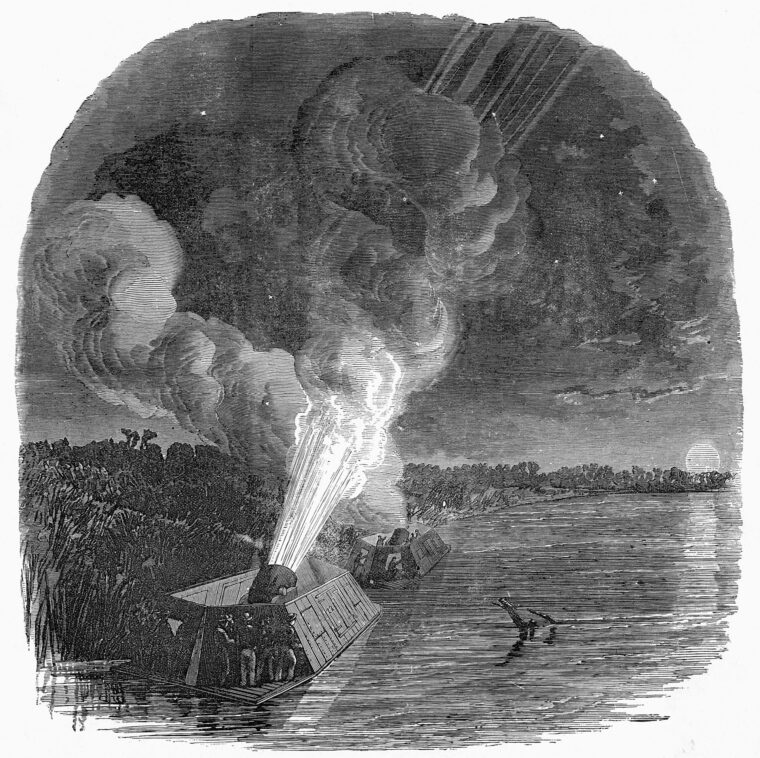

On March 30, Foote had given Walke written orders to run past the Confederate defenses. Walke and his men worked for days placing loose material over the Carondelet’s deck to protect her from plunging shot, and wrapping thick ropes and chains around the pilot house. A coal barge filled with hay and coal, lashed to port, protected the magazine where the Carondelet had no iron plating. Walke would later write, “It was truly said that the Carondelet at that time resembled a farmer’s wagon prepared for market.” In addition, the engineers re-routed the steam’s exhaust pipes to the paddle box to keep them from making a puffing sound when blown through the smokestacks.

What appeared to be the greatest risk to the ironclad was Battery No. 1, a floating battery two miles above Island No. 10. If the defenders there spotted the Carondelet steaming past, they would open fire, giving all the Confederate gunners downstream ample time to prepare a reception.

To eliminate this threat, Foote turned to the brigade of infantry accompanying the gunboats. Their objective was to spike the guns of Battery No. 1 and to capture the sentinels. Colonel George W. Roberts of the 42nd Illinois led 50 volunteers in five boats provided by Foote. Leaving the Benton at 6 pm, the boats drifted along the edge of the river, moving in among the trees short of the battery. At 11 pm, they moved back into the river.

Two Rebel sentries were on high ground behind the flooded battery. When the boats were a few yards from shore, a flash of lightning revealed them and the sentries fired. The Union soldiers did not return fire, but stormed ashore as soon as the boats touched ground. In three minutes Roberts’s men had spiked the guns and returned to their boats, eliminating the threat.

As part of his preparations, Walke augmented his crew with 23 sharpshooters from the 42nd Illinois. The sailors were themselves armed with muskets, boarding pikes and hand grenades. The engineers attached a hose to the boiler to douse any boarders with scalding water. If it appeared the Carondelet might be captured, Walke vowed to scuttle her.

April 4/5 was set as the night to try to run the gauntlet. At first it appeared it was going to be a clear night, so Walke decided not to leave until the moon set about 10 pm. As Walke ordered the master to cast off, “Dark clouds now rose rapidly over us and enveloped us in almost total darkness, except when the sky was lighted up by the welcome flashes of vivid lightning, to show us the perilous way we were to take. Now and then the dim outline of the landscape could be seen, and the forest bending under the roaring storm that came rushing up the river.”

When opposite Battery No. 2, trouble cropped up. Because the steam exhaust pipes no longer terminated in the main stacks, the soot there had dried out. The main fire exhaust ignited the soot, sending columns of flame high over the stack heads. The fire was put out, but a short time later the soot flared again. Although the Union men extinguished it a second time, the Confederates had seen enough and opened fire.

Only two men were on the deck of the Carondelet. Seaman Charles Wilson stood on the bow where the waves splashed over the prow to knee-level. Casting the leaded line into the river, he called out depth levels to Theodore Gilmore by the pilot house, who repeated the message to the pilot, William Hoel. Hoel had volunteered to pilot the ironclad because of his familiarity with the Mississippi before the war. At one point, a lightning flash revealed the Carondelet was about to ram Island No. 10. Hoel brought the helm hard to starboard to avoid running aground.

As they passed Island No. 10, an officer on the Carondelet heard a Confederate officer shout, “Elevate your guns!” Walke speculated that the Confederates had depressed their guns to keep the rain out. So he had Hoel steer close to the island believing the Confederates would overshoot. They did.

The final obstacle was the floating battery at the end of the island, which Walke called the “war elephant” of the Mississippi. The floating battery fired six or eight shots and scored the only hit of the night. A ball struck the coal barge and was later found embedded in a bale of hay.

By midnight the Carondelet arrived at New Madrid having suffered no casualties. Walke ordered a ration of rum distributed, or in the parlance of the day, the crew “spliced the main brace.”

On the night of April 6, the Pittsburgh repeated Walke’s action by running past the Confederates defenses without suffering any damage.

Now Pope could get his men across and with the protection they needed. He selected for his landing point a place called Watson’s Landing, about midway between Tiptonville and the tip of Madrid Bend. It had rained all night on the 6th and the morning was dark and gloomy with low-hanging black clouds. At dawn, the four regiments of Paine’s division boarded the steamers.

The Carondelet and Pittsburgh dropped down the river past Watson’s Landing, then came about and started upriver. Pounding the Confederate position at close range with their starboard guns, Walke signaled Pope at noon that he had silenced the Confederate guns. Then the transports steamed down the river from New Madrid, the rest of Pope’s army lining the bank and cheering them on.

Days before, Hollis had refused to risk his wooden boats against shore batteries. Now he refused to risk them against the two Union ironclads. Writing years later, one Confederate naval officer complained: “One day we received information that the tinclad was ferrying the men of General Pope’s army over to a point above Tiptonville, and the general commanding at No. 10 urged Commodore Hollins to attack the gunboat with his fleet, for if the enemy got possession of Tiptonville, and the road by which supplies were sent to No. 10, the evacuation or capture of that place was certain. Commodore Hollins declined to comply with the request of the general, saying that as the Carondelet was ironclad, and his fleet were all wooden boats, he did not think he could successfully combat her.” Three captains asked Hollins for permission to attack the ironclads, but were refused.

A spy told Pope the Confederates had abandoned most of their positions along the river and were withdrawing toward Tiptonville. Pope signaled Paine to leave a guard at the landing and to press on to Tiptonville with his division. Once the steamers had unloaded Paine’s division, Pope had them ferry Hamilton’s division across to support Paine.

The same terrain features that had stopped a Union advance overland now prohibited the Confederates from withdrawing. The only means to escape south of Tiptonville was along the riverbank, where any refugees would be susceptible to fire from the Union gunboats. A few men escaped across Reelfoot Lake, but the main force was trapped between Tiptonville and Island No. 10.

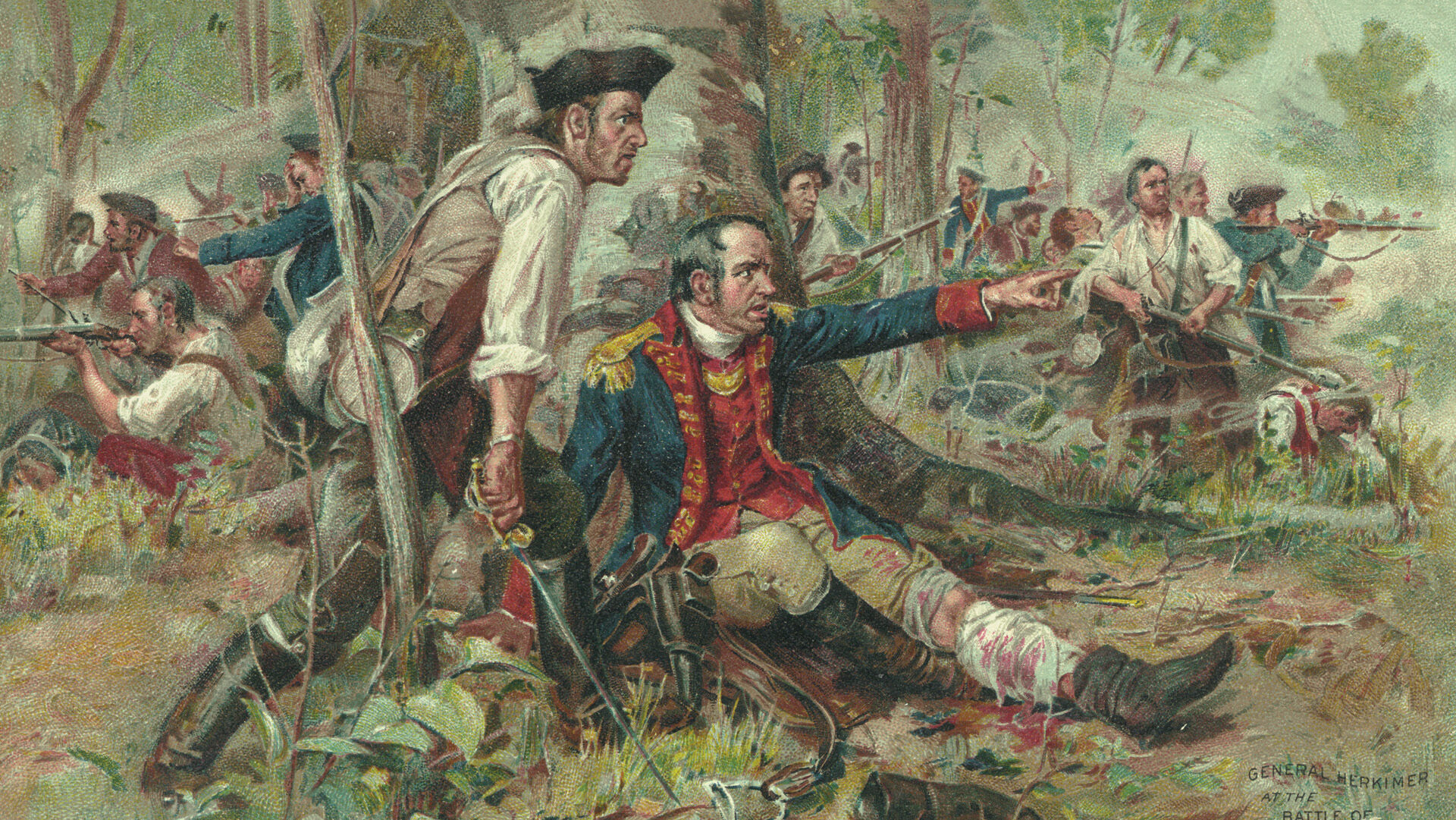

Upon landing at Watson’s Landing, Paine decided that speed was key to capturing the Confederates. Paine’s first brigade led the advance, followed by the second brigade. Almost as soon as they set out, the advance and flankers began sending in prisoners. Nine miles down the road, Paine came across a strong force of Confederates deployed in line of battle. Paine deployed to attack, but before he could the enemy fled. The Confederates reformed, but a volley from a Union skirmish line sent them fleeing again. This happened several times until the Union force reached the Confederate camp.

Mackall knew the only means of escape was along the riverbank. If the two Union ironclads remained at Watson’s Landing to protect the crossing, his men might be able to escape unscathed. Paine’s aggressive pursuit kept him from organizing anything. The Confederates were boxed in. Paine bivouacked for the night, and at 2 am April 7, a staff officer from Mackall arrived with a note offering the unconditional surrender of the entire force. The Confederates tried to scuttle the floating battery and let her drift downriver where she eventually became lodged against the river bank. The defenders on the island waved white flags to signal the Union Navy they wanted to surrender.

Pope claimed to have captured three generals, 6,000 men, 7,000 stands of small arms, 23 heavy guns, and 30 field artillery, and all without the loss of a single man. This was a bad enough loss for the Confederacy, but the loss of geography was worse. The North had a new hero—high-foreheaded, full-bearded John Pope.

Perhaps the epitaph for the Island No. 10 campaign was written by Edward Pollard, an editor for the Richmond Examiner during the war. “The Southern people had expected a critical engagement at Island No. 10, but its capture was nearly accomplished without it; and, in the loss of men, cannon, ammunition, and supplies, the event was doubly deplorable to them, and afforded to the North such visible fruits of victory as had seldom been the result of a single enterprise.”

The Union triumph at Island No. 10, coupled with the victory the same day at Shiloh, made the Confederate position along the central Mississippi untenable. Corinth would not fall for another two months, but when it did, the Confederacy would have precious little of the Mississippi River for transport, trade, or even for moving armies across, save the stretch around Vicksburg, some 330 river miles below Island No. 10.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments