By Al Hemingway

The Allies eyed New Britain as a key prize in General Douglas MacArthur’s island-hopping strategy, but the ferocious combat—and the terrible weather and terrain—would take its toll.

“In this region hot, humid climate produces that type of jungle known as ‘rain forest,’” write U.S. Marine historians Lt. Col. Frank O. Hough and Major John A. Crown in their monograph The Campaign on New Britain. “Giant trees towering up to 200 feet into the sky above dense undergrowth lashed together by savage vines as thick as a man’s arm and many times as tough … [D]ecay lies everywhere just under the exotic lushness, emitting an indescribable odor unforgettable to anyone who has lived it. Insect life flourishes prodigiously: disease-bearing mosquitoes and ticks, spiders the size of dinner plates, wasps three inches long, scorpions, and centipedes. [Also] alligators and giant snakes of the constrictor species.”

It was not a paradise by any stretch of the imagination. Nonetheless, the island of New Britain was becoming increasingly important to the Allies during the fall of 1943. A volcanic, harsh land, New Britain is the largest island in the Bismarck Archipelago at nearly 400 miles long and about 40 to 50 miles wide at various points. In addition, it possesses a long, spiny mountain range that traverses the island. Besides the horrible terrain, diseases such as malaria, typhus, scurvy, and beriberi were rampant.

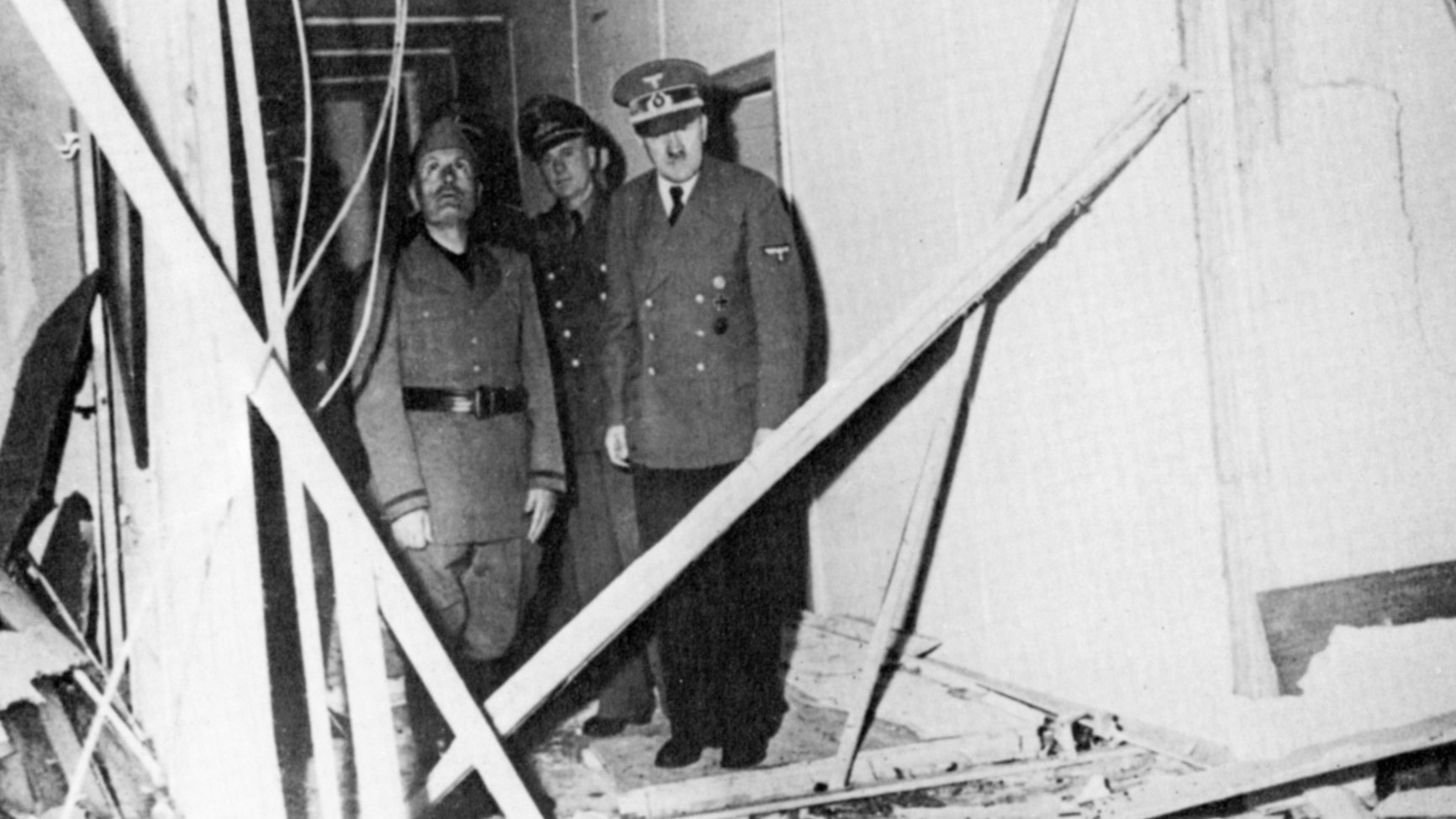

The Japanese captured Rabaul on January 23, 1942. They wasted no time in transforming this once-sleepy German town into a formidable advance base. It soon became the headquarters of General Hitoshi Imamura, commanding general of the Japanese 8th Area Army. During its heyday, Rabaul had five airfields, approximately 100,000 troops stationed there, an excellent deep-water port, and “the fanciest brothel east of the Netherlands Indies.” As with other islands and countries the Japanese occupied during the war, their treatment of the native inhabitants was appalling. Atrocities including murder and rape were commonplace.

By 1943 General Douglas MacArthur, commanding general Southwest Pacific, was in the midst of his “island-hopping” campaign. In early September, Australian and U.S. troops took Salamaua in New Guinea, and 10 days later marched into Lae. In early October, Finschafen was recaptured, and the Allied grasp on the eastern part of New Guinea was taking shape.

All movement ceased when the planners cast a wary eye on the western part of New Britain, however. A short distance from New Guinea, across the Vitiaz Strait on the western end of New Britain, the Japanese had established an airdrome at Cape Gloucester. They had anticipated a move against the region and reinforced it with 10,000 troops under Maj. Gen. Iwao Matsuda. Here, Matsuda had units of the 53rd and 141st infantry regiments. Also, to the south, were an additional thousand men at Arawe. In all, the enemy troop strength was nearly 11,000 soldiers. Unfortunately, their ranks were filled with many engineers and not battle-hardened infantry personnel because of the construction of the airdrome. However, the Japanese were still full of fight and dug in to await an impending assault.

Not wasting any time, Allied planners devised a scheme for the neutralization of western New Britain to protect MacArthur’s right flank as he leapfrogged along the northern New Guinea coast. First, the 112th Cavalry Regiment would land at Arawe on December 15, 1943 to “seize and defend a suitable location for the establishment of light naval facilities.” Also, this landing would divert attention from the major amphibious attack to take place several weeks later at Cape Gloucester itself.

In the early morning hours of the 15th, U.S. Army troops waded ashore and swiftly advanced inland with little opposition. By late afternoon, the soldiers had secured the Arawe Peninsula. With this accomplished, the enemy’s supply line from its main base at Rabaul had been cut.

With Arawe in Allied hands, the action shifted to Cape Gloucester. The Fifth Air Force saturated the area with over 4,000 tons of bombs from December 15-25. So much ordnance was dropped that pilots in future bombing raids would jokingly say, “Let’s Gloucesterize the place.”

As dawn broke on December 26, the 1st Marine Division, headed by Maj. Gen. William H. Rupertus, was off the coast of Cape Gloucester to commence its landing. Matsuda’s men braced themselves to meet “the butchers of Guadalcanal,” as Tokyo Rose referred to the Marines.

Prior to their landing, Consolidated B-24 Liberator heavy bombers inundated the landscape with additional bombs while fighter planes loomed overhead, keeping a watchful eye out for any Japanese Zeros. After they dispensed their loads, North American B-25 Mitchell medium bombers followed close behind and carefully crisscrossed the area, hitting potential targets. Finally, Douglas A-20 Havoc bombers raced in, bombing and strafing any other enemy positions, particularly the beaches. As the assault was imminent, the B-25s unleashed white phosphorous on Target Hill, a prominent terrain feature near the beaches, to obscure the view so the enemy could not observe the landing.

Just before 8 am, Colonel Julian N. Frisbie’s 7th Marines drew the job of going ashore first and setting up a beachhead perimeter. On 500-yard-long Yellow Beach 1, the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines wasted no time in getting on the beach from their LCIs (Landing Craft, Infantry). Likewise, on Yellow 2 the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines began advancing toward Target Hill and Silimati Point.

But it wasn’t the enemy that provided the biggest problem to the Marines on the initial landing; it was the massive wall of jungle that greeted them. Men became mired in the mud. Some sank up to their shoulders in sinkholes. Others less fortunate slipped and wrenched their ankles and, in some cases, broke their legs. During the course of the campaign, 20 Marines were killed by falling trees and at least three by lightning. One unfortunate Army officer lost his arm to an alligator. It was a hell on earth.

The sound of machetes soon could be heard hacking away at the viscid undergrowth. Ironically, this area was marked on the maps as the “damp flat.” One Marine remarked sarcastically, “It’s damp all right. It’s damp clear up to yer ass!” The mud was so thick, the heavier vehicles sank. One officer watched in utter amazement as a piece of equipment “bogged down while crossing the swamp, and all that remained above the mud was five inches of the gun shield and the driver’s seat, exhaust pipe, and a few levers of the tractor.”

Back on the beach, the Marines were offloading as much equipment and supplies as possible before the LSTs (Landing Ship, Tanks) had to pull away. Corporal Carl Meinelt recalled: “As we finished our task, the LST was leaving when a Japanese Zero came roaring in at treetop level toward the beach. You could actually see the pilot’s face—he was that low. Right behind him—I don’t think they were one hundred yards apart—were two B-25s in hot pursuit. The Zero never fired at us for obvious reasons, even though we were perfect targets. He was too busy trying to avoid the other aircraft. As he left, the plane banked off over the ocean. I’m almost sure he was hit because I saw a puff of smoke as it flew away. It was exciting. I jumped from pile to pile so I wouldn’t miss any of the action.”

As the 7th Marines were digging in, the 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines moved through their positions to commence the drive to take the airdrome. It wasn’t long before the Leathernecks encountered a fortified series of rifle trenches and bunkers in their path.

As the enemy Nambu machine guns suddenly chattered, Company K went into action. However, the miserable weather conditions caused bazookas and flamethrowers to malfunction. The unit’s commander and executive officer were killed outright.

Fortunately, the Marines commandeered an LVT (tracked vehicle) that was bringing ammunition and water forward. When the vehicle became wedged between two trees, the Japanese scurried from their holes and shot and hacked to death the men firing the machine guns. But the driver remained calm and dislodged the LVT and drove it over a bunker, caving it in. As the enemy swarmed from their death trap, riflemen picked them off.

As darkness approached, Marines dug in and kept a watchful eye for the enemy. But another foe was waiting. In the wee hours of December 27, a “terrific storm hit the Cape Gloucester area.”

“It was unreal,” Meinelt later remembered. “It rained for weeks without stopping. And when I say rain, I mean RAIN! Nine inches fell in one night, causing a river to alter its course, and completely wiped out two regimental command posts. Cape Gloucester was dark and dismal. I swear the sun never appeared….”

In the midst of this horrific monsoon, Japanese troops, the 2nd Battalion, 53rd Infantry, struck the Marine perimeter. “The wind roared in from the Bismarck Sea at hurricane velocity bringing down giant trees with rending, splintering crashes,” wrote Hough and Crown. “Lightning, striking close by, blinded men, and deafening thunder drowned out the noise of gunfire.”

Because of the intensity of the storm, the enemy failed to capitalize on a breach in the lines between the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 7th Marines. The fighting was nonetheless vicious, as Lt. Col. Odell M. “Tex” Conoley described: “Rain filled up the foxholes and the men were forced to get on top of the ground. It was a choice of drowning or getting shot … 81mm and 60mm mortar fire through the treetops laid ‘by guess and by God’ was invaluable in these attacks.”

While the 7th Marines defeated the Japanese Banzai attack on their beachhead perimeter, the 1st Marines were gearing up to capture the airdrome. The attack was postponed until almost noon while the infantry waited for several platoons of medium tanks to reach their positions.

As the assault jumped off, the Marines once again ran headlong into a labyrinth of rifle trenches and log bunkers. This time the enemy also had 75mm artillery pieces and antitank guns at their disposal.

For the next four hours the two opposing forces were locked in combat. One Marine officer later wrote: “We encountered 12 huge bunkers with a minimum of 20 Japs in each. The tanks would fire point blank into the bunkers. If the Japs stayed in the bunkers, they were annihilated. If they escaped out the back entrance, the infantry would swarm over the bunker and kill them with rifle fire and grenades.”

When the fighting ceased, the Leathernecks had eliminated all the Japanese positions and counted 266 dead. The Marines lost nine killed and 36 wounded. Originally called Hell’s Point, General Rupertus later renamed the site Terzi’s Point after the commander of Company K who was killed there.

As the airdrome was being overrun, the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines, under the leadership of Lt. Col. James M. Masters, Sr., had landed on Green Beach on D-day. This area was southwest of Yellow Beaches 1 and 2 near the villages of Tauali and Sumeru.

Masters was charged with severing the coastal routes near Mount Talawe to halt the retreat of the airdrome defense forces or its being reinforced by other enemy units to the south. Also, he was to look for any other usable paths in the area, which were always a premium on Cape Gloucester.

For the next three days, Masters’ men, or “Masters’ Bastards” as they referred to themselves, aggressively patrolled the region but, with the exception of a few minor skirmishes, found no major Japanese force.

However, on the same day the Leathernecks were closing in on the airdrome, Masters’ unit started receiving greater volumes of small-arms fire. At 2 am on December 30, the Japanese struck. The fighting was close range. At times, mortar fire was only 15 to 20 yards in front of the perimeter. The 75mm rounds of Battery H, 2nd Battalion, 11th Marines were brought to bear on the charging enemy troops. As the casualties mounted, a provisional rifle platoon from the artillery battery augmented the thinning line.

Gunnery Sgt. Guiseppe Guilano, Jr., grabbed a light machine gun and, cradling it in his arms, moved up and down the perimeter wherever he was needed. Firing from the hip, the senior NCO proved invaluable in breaking the enemy assault. “The following morning I saw Guilano’s arms taped up as a result of burns received while carrying a hot machine gun around,” said Captain T.R. Galysh, commanding officer of H Battery, 2nd Battalion, 11th Marines.

In their futile attempt to overrun the Marines’ lines, the enemy lost 89 killed, and five prisoners were taken. The hotly contested combat was soon called “The Battle of Coffin Corner.” Masters’ men remained in the area for several more days before rejoining the main body at Cape Gloucester.

While the Battle of Coffin Corner raged, the rest of the 1st Marines, along with the newly arrived 5th Marines, converged on the airdrome. Company F, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines ran headlong into 30 to 40 enemy bunkers. For the next three hours, the infantry, together with medium tanks, knocked out the defensive positions. The 1st Battalion, 5th Marines also came across Japanese trenches and began to eliminate them.

Companies I and K, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines moved in from the west and forced the enemy defenders from their prepared bunkers. As their opponents ran up Razorback Hill, a machine-gun section from Company A, 1st Battalion, 5th Marines raked the retreating Japanese. Not only had the Marines taken the airdrome, but Razorback Hill as well.

Rupertus was delighted when word reached him that the airdrome was in Marine hands. He wasted no time in dispatching a message to Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger, commander of the Sixth Army, which read, in part: “First Marine Division presents to you as an early New Year’s gift the complete airdrome of Cape Gloucester. Situation well in hand due to fighting spirit of troops, the usual Marine luck and the help of God…. Rupertus grinning to Krueger.”

But upon closer examination, the Marines soon discovered to their dismay the dreadful condition of the two airstrips. The runways had been pockmarked with shell craters from the bombings. Also, the enemy had left behind the remnants of over a dozen planes scattered throughout the area. Soon the bulldozers from the U.S. Army’s 1913th Aviation Engineer Battalion and the 864th Aviation Engineer Battalion were working on the runways to get them into shape.

However, even with the airdrome in Marine hands, the fight for Cape Gloucester was not over. Brigadier General Lemuel C. Shepherd, assistant division commander, was ordered to “clear the enemy from the Borgen Bay area.”

But the enemy had other plans. Colonel Kenshiro Katayama, commanding officer of the 141st Infantry Regiment, decided to retake Target Hill. Defending this area was Company A, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, which quickly ascertained what the Japanese were up to when they could hear them coming up the steep incline in front of the Marine lines.

First Lieutenant Shinichi Abe’s 5th Company, 141st Infantry led the way. Unfortunately, Abe’s men ran smack into a determined Marine machine-gun crew, which refused to yield any ground. When the firing had ended, the squad had expended 20 belts of ammunition.

Katayama’s plan to recapture Target Hill had failed miserably. The attack had not been well coordinated, and the enemy botched an attempt to breach the Marine lines. For this, the 5th Company and the 2nd Battalion, 53rd Infantry were virtually annihilated, with more than 200 enemy dead. Colonel Katayama soon realized he was up against a much greater force than he had been led to believe.

On January 2, 1944, Brig. Gen. Shepherd ordered “an unusual scheme of attack, with an unbroken line hinging on the beachhead, swinging to attack southeastward on a front of about 1,000 yards.” He sent the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines to the right to redeploy. As this was transpiring, the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines advanced to the right with all its companies abreast.

Once again, the unforgiving jungle of New Britain proved to be a thorn in the Marines’ side. Infantrymen wielded machetes in an effort to cut their way through the thick undergrowth, delaying their forward movement. This caused the line to form the letter “U” with the enemy fortifications in the center on three sides.

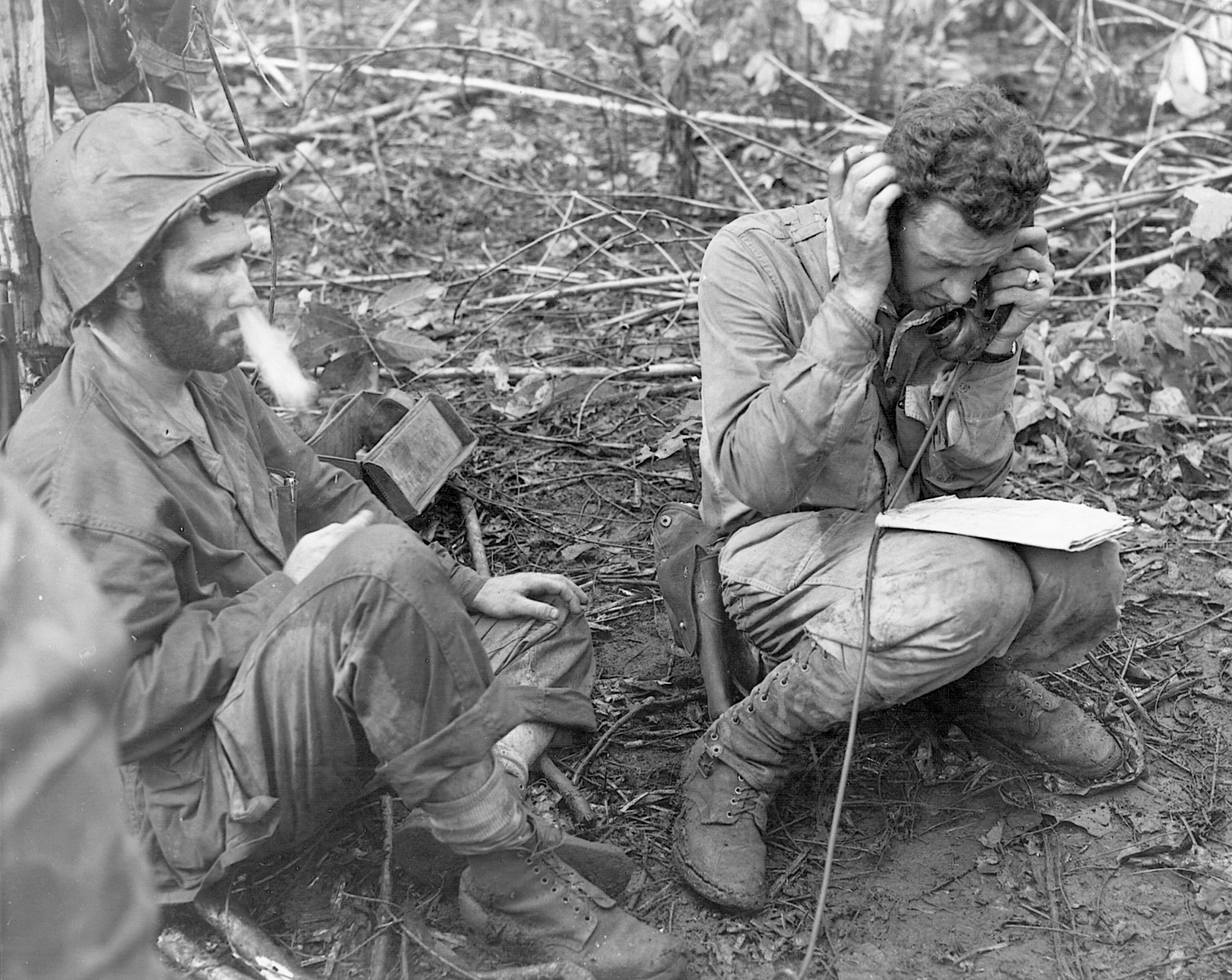

Here, the Leathernecks encountered a stream where the Japanese had established their defenses. Every time the infantrymen attempted to cross, they took automatic weapons, mortar, and rifle fire. The battalions tried again and again to cross the creek but were repulsed. While taking refuge from an enemy mortar barrage, one Marine later recalled: “[I saw] a kid sitting there in his foxhole. He didn’t have any head. He just had a neck with dog tags on it.” Soon, the Marines called it “Suicide Creek.”

Lieutenant Colonel Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller took over command of the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines and wasted no time in assessing the situation. He alerted the regimental headquarters that he needed half-tracks, tanks, and bulldozers from the 17th Marines to eliminate the enemy’s positions near the stream.

“We have enough power here to drive,” he growled to his junior officers, “and we’re going to drive. Blow your way through, and think of nothing else.”

The following day a bulldozer began to make a path through the jungle. The tanks could not cross because the stream banks were 10 to 12 feet high. The dozer began pushing the mud into the creek bed so they could cross the stream and provide much-needed support for the infantry.

Two bulldozer drivers were wounded at the outset. The riflemen started pouring fire at the enemy to give the exposed drivers some cover. The third driver, using his ingenuity, lay down in the bulldozer and operated the vehicle with a shovel and an axe handle and completed the dangerous task. Soon the tanks lumbered across the stream, blasting the earth and log bunkers. The infantry followed closely, eliminating pockets of enemy resistance. By nightfall, the line had been straightened out and, once again, the perimeter was secure.

Next, Shepherd wanted Hill 660, another prominent location in the area, secured as well. Lieutenant Colonel Henry W. Buse’s 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines was selected for the demanding job. Captain Joseph Buckley of Weapons Company, 7th Marines also joined the attacking force with two half-tracks, two light tanks, a 37mm gun platoon, Army DUKWs (amphibious trucks) equipped with rocket launchers, two platoons from 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, and a platoon of Pioneers from the 2nd Battalion, 17th Marines with a bulldozer.

“The terrain here was especially difficult,” wrote Marine historians Hough and Crown. “The rising ground to the approach dropped sharply to the northern base of the hill proper, thus forming a deep gulch, both slopes cluttered with trees and jungle undergrowth, and strewn with boulders. So steep was the grade that in many places the men were obliged to sling their weapons and claw their way upward on all fours.”

As the Leathernecks were inching their way to the top of Hill 660, the lead company was soon under fire from Japanese machine guns. As Company I became pinned down, Company L tried to negotiate to the right to assist their fellow Marines. Unfortunately, they too were bogged down as enemy automatic weapons fire opened up on them.

The 75mm pack howitzers of the 11th Marines hammered the enemy machine-gun nests, and the infantrymen were able to withdraw and establish a more defensible position.

Buckley’s group was achieving more results in its climb up Hill 660. The group moved around the eastern side of the hill with relative ease. Setting up a perimeter, the young captain placed his tanks and half-tracks in supporting positions.

At 9 am the next day, the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines continued the assault on Hill 660. The tanks were brought forward to assist the riflemen, and by mid-afternoon the Marines had the area half circled. Ascending the southern part of 660, one group of riflemen almost reached the crest of the hill when they were met by heavy machine gun fire. They called for 60mm mortar support, which destroyed the Japanese positions. When the automatic weapons went silent, the Marines charged up and took the hill.

Some of the Japanese fled down the northeastern slope and ran right into Buckley’s perimeter. The group opened fire, killing four enemy soldiers trying to cross a stream. The Pioneers mowed down eight more attempting to breach their lines.

That evening, the exhausted Marines dug in on the summit of Hill 660. “One individual committed the error of leaving his foxhole after dark and crawled under another Marine’s hammock,” said Meinelt. “We used hammocks whenever we could to stay above the water. Anyway, we were pretty punchy at that point, and the Marine in the hammock shot and killed him. It was a real tragedy.”

The Japanese made one last vain attempt to recapture Hill 660. On January 16, a Banzai charge of “howling fanatics to the strength of approximately two companies” hurled themselves at the Marine perimeter. The fighting was hand to hand. Lieutenant Colonel Buse used 60mm and 81mm mortar fire to sandwich the enemy between the shelling and annihilate them. This use of supporting arms caused the Japanese to break off the attack. The enemy departed, leaving 110 of their dead behind.

With the brutal combat for Hill 660 over, the enemy soon vanished into the jungle. Patrols were sent out to locate the elusive Japanese. Boarding LCMs (Landing Craft, Mechanized), the Marines hopped along New Britain’s northern coast to cut off the enemy’s retreat.

Reaching Talasea on the Williaumez Peninsula, they set up a defensive perimeter around a small airfield. Nothing more than a grassy field, the tiny runway was utilized for light Piper Cub aircraft. These small aircraft were quite useful in spotting for artillery and watching for enemy troop movements.

Here, the Marines halted their advance. At the end of April, the Leathernecks had one brief firefight with the retreating enemy. With this action over, the Japanese defense force that had occupied and fought at Cape Gloucester was either dead or had escaped into the jungle and died of starvation, disease, or at the hands of vengeful natives. With the western end of New Britain in Allied hands, MacArthur’s right flank was now secured, and he could once again advance along New Guinea’s northern coast.

Over the years, numerous historians have concluded that the entire Cape Gloucester operation was unnecessary. MacArthur’s fear that the Japanese would strike at him from Cape Gloucester was unfounded, they claim. He could have taken New Guinea without New Britain’s western end being secured. To support this supposition, the proposed plans for a major airstrip at Cape Gloucester never materialized. Also, no PT boat base was ever constructed at Arawe.

Nevertheless, those individuals who suffered through the green hell of New Britain can be justifiably proud of their service. During the campaign, the Marines sustained 310 killed and 1,083 wounded. In contrast, the Japanese lost 5,000 men. The Allies endured unspeakable weather and climatic conditions and, in the end, defeated a fanatical enemy.

But what of the Japanese at Rabaul? “They operated as if we weren’t even there,” remarked Meinelt. “We wanted the western end of New Britain anyway…. The Japanese at Rabaul, for all intents and purposes, were isolated.”

For the remainder of the war, the 8th Area Army waited for a massive assault that never came. Allied troops remained on the western portion of New Britain and the Japanese at Rabaul on the eastern end. Separating them was the ghastly “green inferno” of the island. One Australian officer quipped: “And now 40,000 Japanese were held in that same Gazelle Peninsula by 29 coastwatchers and 400 armed natives.”

General Hitoshi Imamura, commanding the 8th Area Army, surrendered his ceremonial sword to Australian Lt. Gen. Vernon A.H. Sturdee on September 6, 1945, on the deck of a British warship in Simpson Harbor. The Japanese reign of terror at Rabaul and on the island of New Britain was finished. n

Al Hemingway is a U.S. Marine Corps veteran of the Vietnam War. He is the author of Our War Was Different, published by Naval Institute Press, and writes often on military history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments