By James I. Marino

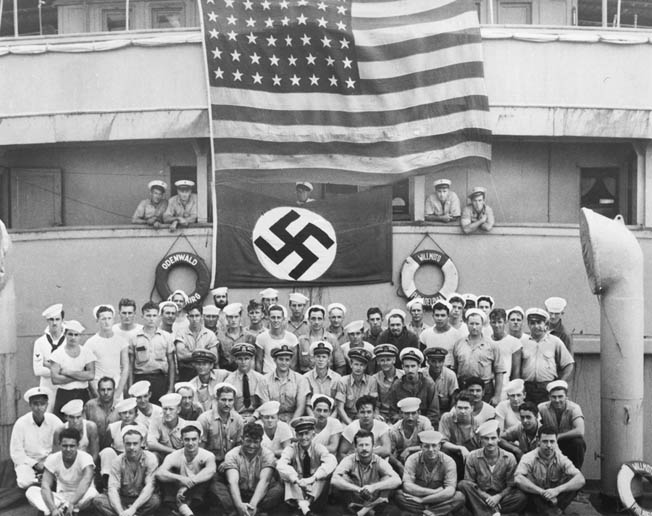

Between September 1939 and December 1941, the United States moved from neutral to active belligerent in an undeclared naval war against Nazi Germany. During those early years the British could well have lost the Battle of the Atlantic. The undeclared war was the difference that kept Britain in the war and gave the United States time to prepare for total war.

With America’s isolationism, disillusionment from its World War I experience, pacifism, and tradition of avoiding European problems, President Franklin D. Roosevelt moved cautiously to aid Britain. Historian C.L. Sulzberger wrote that the undeclared war “came about in degrees.” For Roosevelt, it was more than a policy. It was a conviction to halt an evil and a threat to civilization. As commander in chief of the U.S. armed forces, Roosevelt ordered the U.S. Navy from neutrality to undeclared war.

It was a slow process as Roosevelt walked a tightrope between public opinion, the Constitution, and a declaration of war. By the fall of 1941, the U.S. Navy and the British Royal Navy were operating together as wartime naval partners. So close were their operations that as early as autumn 1939, the British Ambassador to the United States, Lord Lothian, termed it a “present unwritten and unnamed naval alliance.” The United States Navy called it an “informal arrangement.”

Regardless of what America’s actions were called, the fact is the power of the United States influenced the course of the Atlantic war in 1941. The undeclared war was most intense between September and December 1941, but its origins reached back more than two years and sprang from the mind of one man and one man only—Franklin Roosevelt.

Two Navies Unprepared For War

When war broke out in September 1939, the Royal Navy and the German Kriegsmarine were both unprepared. Land-minded Adolf Hitler prepared his army and air force but had not given his navy time to build the necessary submarine or surface fleets for a naval war against Britain. Since Hitler planned for a war of short duration, he considered interference with the Atlantic sealanes a means to defeat Britain. However, Hitler preferred to eliminate continental powers first and then make the British “see reason.”

The German naval staff, led by Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, and the U-Boat Service, commanded by Admiral Karl Dönitz, held the opposite view of the war. They were convinced it would be a long war and that it would have to be won in the Atlantic. The Kriegsmarine believed that Britain had to be hit decisively in the Atlantic theater before America’s power and economic impact became decisive. Dönitz believed that 300 submarines and wolfpack tactics could strangle Britain. But Hitler launched the war almost three years before the naval construction program was completed. This left the German Navy short of submarines and surface vessels. At the start of the war, Hitler also restricted the U-boat campaign.

The British instituted the convoy system at the start of the war. First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill remembered the lessons of World War I and reestablished the convoys. However, the Royal Navy engaged in the war sooner than they hoped. The British shipbuilding program, especially escorts, would not produce results until 1941. Until the new escorts came on line, a convoy escort limit had to be drawn about 300 miles west of the British Isles.

The British convoys had four major weaknesses: (1) a shortage of escorts, usually two or three ships; (2) ASDIC (a method of underwater detection) was ineffective beyond 1,000 yards; (3) RADAR (improved detection) was too primitive to give early or accurate warnings of night attacks; and (4) lack of air cover. As much as the Royal Navy lacked at the start of the war, it did have the capacity to blockade Germany, bottle up most of the German surface fleet, and handle the few U-boats and raiders that operated on the high seas.

But Churchill, unlike Hitler, recognized that the war would be a long, total war. As such, he saw the escort shortage as a major weakness. Churchill thought Roosevelt might be persuaded to sell Britain fleet destroyers to fill the urgent need for open-ocean escorts for convoys and inquired about such an arrangement in September 1939. The situation at the outset was decidedly in favor of the Allies.

America’s Inevitable War

The Munich Pact and the failure of appeasement convinced Roosevelt that Germany remained a dangerous threat and that war was inevitable. Roosevelt’s policy for America was dictated by a desire to stay out of war, support the Allies, and prepare America’s defenses. Gerhard Weinberg, in A World at War, wrote, “The American President hoped to avoid open warfare with Germany altogether. He urged his people to aid Britain and he devised a whole variety of ways to do just that; but he hoped until literally the last minute the United States could stay out of war.”

Secretary of State Cordell Hull supported FDR’s position by stating, “Our highest military officers repeatedly said they needed time to prepare our defenses.” Thus, the longer FDR could delay American participation in a shooting war, the better prepared the United States would be. Roosevelt’s basic approach was to do as much as he could for Britain and France without incurring the wrath of American isolationists or driving Hitler to a declaration of war. Roosevelt had the ability to do this.

Admiral Samuel Elliot Morrison described FDR’s strategy: “The President had a political calculating machine in his head, an instrument in which Gallup polls, the strength of armed forces and the probability of England’s survival; the personalities of governors, senators, and congressmen; the personalities of Mussolini, Hitler, Churchill, Chiang, and Tojo; the Irish, German, Italian, and Jewish votes in the approaching election; the ‘Help the Allies’ people and the ‘American Firsters,’ were combined into the fine points of political maneuvering.”

All of these abilities enabled Roosevelt to influence American public opinion while guiding U.S. foreign policy. Roosevelt recognized Great Britain as the front line in America’s defense against Nazi Germany. Even the Times of London termed his position on the Atlantic “a forward strategy despite a neutral status.” However, it was clear that this policy could only be maintained by armed resolution. Since this was to be a forward defense, reaching far into the Atlantic, then the only tool America had was the U.S. Navy.

Projecting Power with the U.S. Navy

The U.S. Navy stood as the shield guarding America. Now the Navy would not only protect the United States but would also project American power into another European war. Roosevlt would use the Navy to test the purposes of the Führer. When Roosevelt realized Hitler was unwilling to confront U.S. policy, the president set to work.

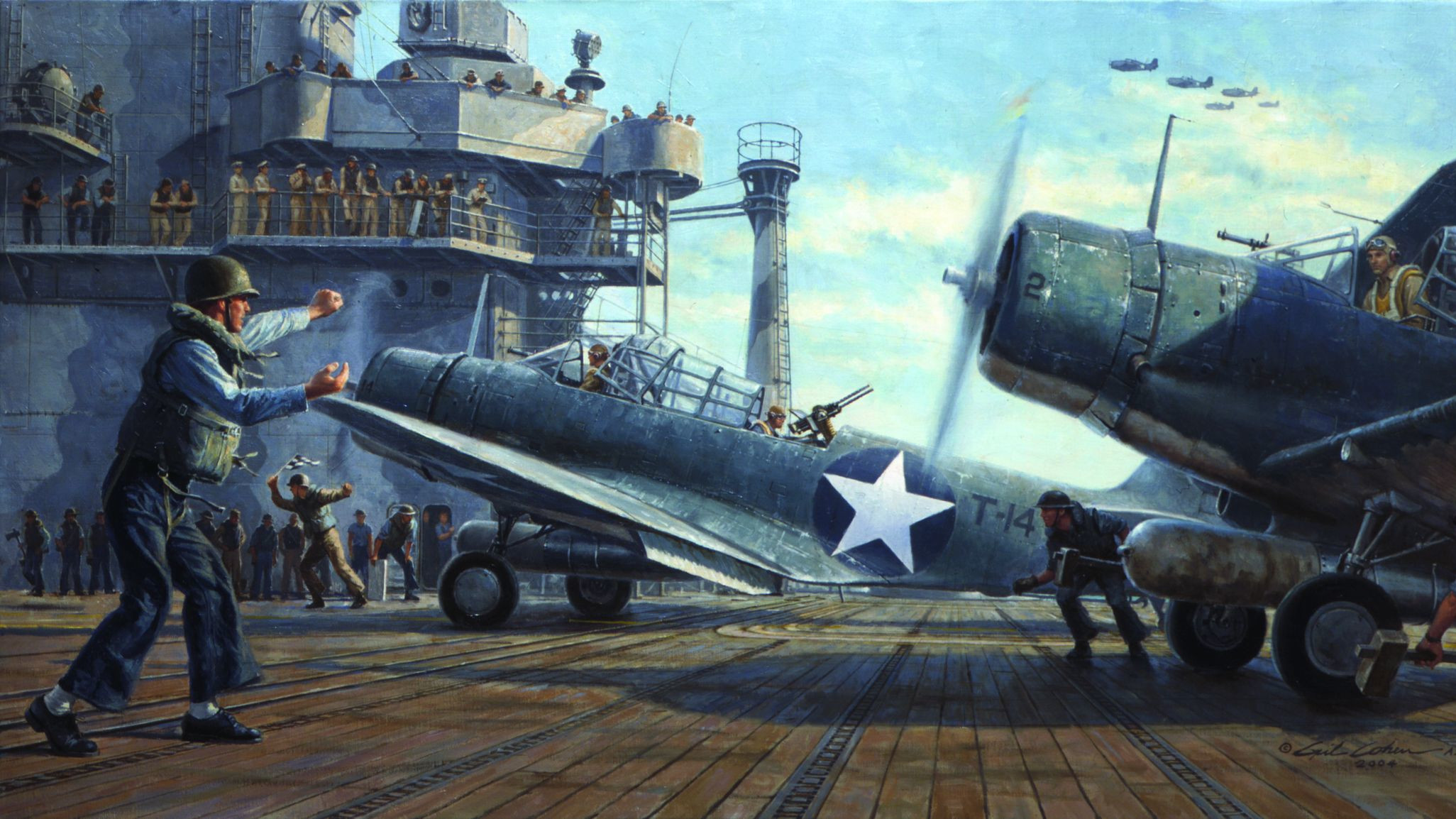

Roosevelt created his instrument in January 1939. In that month he ordered the formation of the Atlantic Squadron. At the time of the Munich Pact, the Atlantic naval strength consisted of just seven cruisers and seven destroyers. With a shift of vessels from the Pacific to the Atlantic, the Atlantic Squadron was born. By the time war broke out in Europe, the squadron consisted of an aircraft carrier, four battleships, a cruiser division, and a destroyer squadron. Roosevelt planned a new role for the enlarged Atlantic force.

Back in the spring of 1939, Roosevelt had informed cabinet members of his plan to inaugurate a naval patrol extending from Newfoundland to South America. In May 1939, under conditions of utmost secrecy, the British Admiralty dispatched a planning officer to Washington to discuss Anglo-American naval dispositions in the event that Britain found herself at war with Germany. In the discussion, it was agreed that “command of the western and southern Atlantic would have to be assured by the United States Fleet.”

In June, at a meeting between the president and King George VI, Roosevelt told the king about the help he planned to give Britain in the event of war. The president sketched his ideas of a Western Atlantic patrol based in Trinidad and Bermuda that would fan out along a radius of 1,000 miles by sea and air. Here Roosevelt’s vision projected almost two years into the future. A few weeks later, in July, Roosevelt secretly but directly proposed to the British Foreign Office that the United States should establish a patrol over the Western Atlantic.

An “American Closed Zone” in the Atlantic

Two days after England and France declared war on Germany, the president ordered the U.S. Navy to organize neutrality patrols. The president also declared a neutrality zone, initially a 300-mile wide strip of ocean along the East Coast of the United States running south through the Caribbean. The object of the patrols was to report and track any belligerent forces approaching the coasts of the United States or the West Indies. The Germans immediately saw that the zones contracted the area in which their commerce raiders could hunt.

Although the German Foreign Office concluded that the “American Closed Zone” was a disadvantage to Germany, it assumed the British and the French would reject it and therefore did nothing about it. The Germans did not know that the zone, in fact, screened a pooling of Anglo-American naval resources and that the British government informed the Americans that the zone was acceptable. The next day, September 6, Roosevelt directed that 110 destroyers be recalled and recommissioned into the Navy. Eventually, 50 of them would be traded to the British. In addition, Coast Guard cutters worked side by side with the U.S. Navy in the Patrol Zone.

On October 2, 1939, the Act of Panama was announced in which the North and South American nations recognized a joint defense of the Western Hemisphere. This legalized any American military action in the Western Atlantic. A week later, Roosevelt ordered the Navy to broadcast in “plain English” the position of belligerent ships. In fact, this was designed only to report the locations of German submarines and to be overheard by British ships escorting convoys. British violations were ignored. For example, on December 14, 1939, the British destroyer HMS Hyperion fired on the German luxury liner Columbus only 350 miles off the coast of New Jersey.

The Lone Battleship Division of the Atlantic Squadron

The condition of the Atlantic Squadron and the U.S. Navy must be examined. Almost 20 years of isolationism and pacifism had resulted in a weakened fleet. The United States Fleet was unprepared to implement the orders, had very little experience, and was shorthanded. The Atlantic Squadron consisted of only a battleship division, with the USS New York, USS Texas, USS Arkansas; one cruiser division; a single destroyer squadron; a patrol wing; and the lone carrier, USS Ranger. In the early months of the war, the Navy relied more on aircraft than ships.

The U.S. Navy gradually affected German U-boat operations. American ships shadowed German merchantmen, U-boats, and raiders, reporting their positions. The U.S. Zone excluded U-boats from areas west of Bermuda. Grand Admiral Raeder protested to Hitler that the zone covered so wide an area—half the Atlantic between South America and Africa—that it severely limited the capabilities of the pocket battleship Admiral Scheer as a commerce raider. Although it hindered the Germans and helped the British, the impact on the American Navy was negative. Training and drills, notably gunnery practice and maneuvers, were all but impossible in the rough seas and bitter cold of the North Atlantic. The duty was dangerous and exhausting; the men thought the patrols pointless and inefficient. A morale problem was building and would eventually have to be confronted.

Despite an occasional foray of German surface vessels into the neutral zone, the Germans made no serious attempt to enter until April 1940, after the occupation of Denmark, when they landed weather teams on the Danish possession of Greenland. In May, the Greenland Council, meeting at Godhaven, adopted a resolution requesting that the United States provide protection for Greenland. Before the United States could quickly or officially act, the Phony War ended and the Germans invaded the Low Countries and France. The neutrality patrol performed one final mission under the old conditions. It was a secret mission. On June 10, the day the French government evacuated Paris, the cruiser USS Vincennes arrived at Casablanca, even though her logs read Lisbon, and took on board 660 cases of gold ingots and 3,129 bags of coins valued at more than $241 million that France wanted to keep out of Nazi hands. The American cruiser carried them to the United States.

Between September 1939 and June 1940, the Royal Navy kept the sealanes open. The Royal Navy focused on protecting the convoys close to the British Isles, knowing that only limited resources were necessary in the Western Atlantic because the U.S. Navy was active there. With the fall of France and the entrance of Italy into the war, the entire situation changed.

98 Ships Lost Per Month

The Battle of the Atlantic began after the fall of France. The German conquest of French ports changed the strategic pattern of the war at sea; possession of the French Atlantic naval bases gave the German U-boats direct access to the Atlantic. It also forced the British to divert shipping from the southwest approaches to Britain to the northwest. Stationed on the French Atlantic coast, the U-boats’ cruising radius was now doubled. This provided the Kriegsmarine with a clear and simple strategic objective with war-winning potential: the defeat of Britain by severing her maritime communications and supply lines.

Although he had only 27 operational U-boats, Admiral Dönitz was ready to unleash his new wolf pack tactic. For the Royal Navy it meant a two-front naval war with the Mediterranean now threatened by the Italians. British escort capabilities were on the ropes. The British, short of escorts, reduced the average escort strength to 1.8 per convoy during the summer of 1940. As a result, between June and September 1940, the U-boats sank 274 ships with the loss of only two submarines. The monthly average of Allied merchant ships sunk jumped from the pre-June 1940 count of 60 per month to 98 per month.

The French surrender, however, directly affected the other side of the Atlantic. On June 13, 1940, Roosevelt presented a fresh defense policy to his military commanders, stating that the United States would be active in the war but with naval and air forces only. This “short of war” memo began the direct path to the shooting war of 1941.

Roosevelt’s Third Term: Expanding the U.S. Navy’s Role in the Atlantic

The fall of France convinced Roosevelt to run for a third term. Cordull Hull wrote in 1948, “The third term was an immediate consequence of Hitler’s conquest of France and the specter of Britain standing alone between conquerors and ourselves. Our dangerous position induced President Roosevelt to run for a third term.”

Roosevelt believed he alone could carry out his undeclared war policy. Running for reelection while carrying out the “short of war” policy required secrecy and deviousness. To carry it off, he and Hull both felt they would have to drop their policy of being frank with the American people.

Thereafter, Roosevelt moved fast. In July, he sent Admiral Robert Ghormley to London to met secretly with the British Admiralty to coordinate U.S. Navy and Royal Navy antisubmarine operations. In August, the United States sent weapons, arms, and the Coast Guard to Greenland to defend its cryolite mines. At the same time, the United States and Canada, a nation at war with the Axis, signed the U.S.-Canadian Mutual Defense Pact. In September, further secret, high-level, military-liaison staff conversations were held in Washington and London.

Roosevelt also announced the “Destroyers-For-Bases Deal,” calling it “the most important action in the reinforcement of our national defense that has been taken since the Louisiana Purchase. Then as now, considerations of safety from overseas attack were fundamental.”

Roosevelt also expanded the neutrality patrol to the longitude 60 degrees east of Greenwich. Roosevelt’s new policy committed America deeper into the war. Chief of Naval Operation Admiral Harold Stark crafted a new war plan in October 1940 based on the premises that Europe was vital to U.S. security and the United States must support Britain to stop Germany.

After his election to a third term, Roosevelt, secure in his leadership, moved the United States closer to participation in war in the Atlantic. No longer encumbered by fear of losing the election of 1940, substantial forms of aid were devised. Lend-Lease was announced early the next year.

Ernest King’s Four Orders

Roosevelt did not feel secure enough to order direct convoy protection, but Admiral Stark, sensitively attuned to Roosevelt’s thinking on naval matters, already had planners blueprinting a “British Isles detachment” to operate out of Northern Ireland and Scotland. On November 12, Stark recommended to the president secret talks with the British, which Roosevelt authorized and commenced in January 1941. As the undeclared war shifted into high gear, Admiral Stark dealt with the Atlantic Fleet’s morale problem by placing Admiral Ernest J. King in command of the Atlantic Patrol.

King began his work by making clear what he wanted through a series of orders to the fleet. The first order, December 20, 1940, dealt with the measures necessary to place ships on a war emergency basis; the second focused on daily exercises at general quarters and damage control while at sea as well as “close attention to orders and instructions.” It may have been an undeclared war, but King saw to it that the Navy was fighting a real war. The third order was devoted to the exercise of command by officers in this period of wartime. The fourth was titled “Making the Best of What We Have.”

King astonished one junior officer by saying he felt the United States really was at war. The officers and sailors began to come around and soon faced their duty and orders with quiet grace. The soon-to-be-designated Atlantic Fleet immediately began darkening ships, manning its guns, practicing damage control, and mentally preparing for war. King pushed his sailors to exhaustion as the United States assumed increasing responsibilities for protecting convoys in the western regions of the Atlantic. Six weeks after King took command, Secretary of the Navy Henry Knox sent him an approving letter. Knox wrote, “I am not surprised at all, but I am gratified, to know that the Commander-in-Chief of the Atlantic Fleet recognizes the existence of an emergency and is taking the proper measures to meet it.”

As 1940 ended, Britain faced financial exhaustion, calamitous shipping loses, the systematic ravaging of England by the Blitz, and the expectation of a German drive through the Balkans. On the plus side, Britain had a naval alliance with the United States and coordinated naval operations with the United States Navy. Also, the “Arsenal of Democracy” was about to open its factories and treasury.

“Belligerent Neutrality”

Joint Chiefs of Staff talks suggested by Stark began on January 29, 1941. They lasted almost two months and resulted in clearly defined American assignments in the undeclared war. Before the meetings, Roosevelt set the guiding principles by which the American staff was to develop a combined strategy with the British. America’s military course would be conservative until its strength developed, and America would be ready to act with what was available. He also warned the Navy to be prepared to convoy.

At these secret meetings, the Americans committed the U.S. Navy to escorting North Atlantic shipping. In the final written agreement, the key passage read: “The principle task of the United States naval forces in the Atlantic will be the protection of shipping of the associated Powers [Britain, United States and invaded European nations].” Also, the British pledged that when America came into the war, covertly or overtly, Canadian naval forces would automatically come under American command. It meant a “neutral” nation would command the ships of a nation at war.

The name given to this undeclared status was “belligerent neutrality.” This meant the protection of the Atlantic convoy routes became part of the American security policy, although Roosevelt denied this fact to the press and public. The two staffs agreed upon further specific operations for the U.S. Navy, which included regular Atlantic patrols, the defense of Greenland, and providing escort for convoys halfway across the Atlantic to be turned over to the Royal Navy at the MOMP, the Mid-Ocean Meeting Point.

Historian Hanson Baldwin described U.S. assignments as a thinly disguised neutrality that became an unrestricted war at sea. With the Navy assignments established, Roosevelt directed that the Navy’s patrol force be greatly expanded, renamed the Atlantic Fleet, and brought to a state of readiness. Roosevelt met with Admiral King at Hyde Park to work out detailed operational plans.

Stark’s reaction to the resulting directive was to tell King, “This step is, in effect, a war mobilization.” In a letter to all his fleet commanders, Stark wrote, “My own personal view is that we may be in the war (possibly undeclared) against Germany and Italy within two months.”

The First Shots of America’s Undeclared War

Casco Bay, Maine, was developed as a U.S. destroyer base. In mid-February, U.S. Marines raised the American flag over a desolate village called Argentia, in Newfoundland, and the U.S. Navy took an active role in convoy protection. Also in February, the Atlantic force attained fleet status and received reinforcements from the Pacific: the carrier USS Yorktown, three battleships, USS New Mexico, USS Mississippi, USS Idaho, and several cruisers and destroyers.

With the passage of Lend-Lease in March 1941, the pace of America’s involvement in the naval war increased. In March, American officers arrived in Britain to select bases in Scotland for American destroyers. On March 17, the Coast Guard cutter Cayuga left Boston with the Greenland Survey Expedition to locate military airfields, seaplane bases, radio stations, meteorological stations, and aids to navigation and to furnish hydrographic information from Greenland.

On April 4, American shipyards became available to British and Allied vessels for repair and refitting. Just five days later the British battleship, HMS Malaya, arrived in New York for repairs, paid for by Lend-Lease funds. On April 7, the U.S. naval base on the Crown Colony of Bermuda was commissioned. A de facto U.S. protectorate over Greenland became formally legalized on April 9. The president told the American public that a loss of Greenland or Iceland “would directly endanger the freedom of the Atlantic and our own American physical safety.”

The U.S. Coast Guard established the Greenland Patrol in June and July 1941. By September, Army engineers had constructed 85 buildings and three miles of access roads. The jeeps that were flown in were Greenland’s first automobiles. Soon a civilian contractor’s force arrived to begin work on the airfield itself. BLUIE West 1 was to become the major U.S. Army, Navy, and Coast Guard base in Greenland. Thousands of aircraft would stop there for refueling on their way to Britain. The day after the announcement of the Greenland occupation, the first shots fired by an American warship occurred.

The destroyer USS Niblack dropped depth charges on a U-boat while conducting rescue operations near a torpedoed Dutch freighter off the coast of Greenland on April 10, 1941. This was the first combat action taken by an American naval vessel against the Axis powers. Subsequently, the patrol zone was extended to the 26th longitude, and Roosevelt requested that the British Admiralty notify American naval units in “great secrecy” of its convoy dates, plans, and destinations, “so that our patrol units can seek out any ships or planes of aggressor nations operating west of the new line.” On April 18, the Navy Department authorized the construction of a destroyer base at Londonderry, Northern Ireland, and one on the west coast of Scotland, along with seaplane bases in Northern Ireland and northern Scotland. American forces were now planted on territory clearly in Europe without a declaration of war.

Operation Plan 3-41

On April 18, Admiral King issued Operation Plan 3-41, which officially designated the water west of the 26th longitude, just west of Iceland, to be part of the Western Hemisphere and stated that any transgression of that line by the Axis was to be viewed as unfriendly. Operating under this order, the Coast Guard cleaned out the German weather stations on Greenland. These turned out to be the first land combat actions of the undeclared war.

America replaced British merchant losses in the Atlantic. Fifty first-class tankers were transferred to the British maritime shuttle, replacing the 42 British tankers already sunk. Later, an additional transfer of 75 Norwegian and Panamanian tankers to the British doubled their tanker fleet. In mid-May, Churchill assessed America’s impact in a memo to South African General Jan Smuts, which stated, “We shall certainly get increasing American help in the Atlantic, and personally, I feel confident our position will be strengthened in all essentials before the year is out.” But it was also in May that the first American merchantman was sunk in the Atlantic. The undeclared war had its first casualty.

More and more each day, American forces and personnel became involved in combat. The Coast Guard cutter Modoc was in sight of the naval duel between the battlecruiser HMS Hood and German battleship Bismarck. In fact, it was an American adviser, Ensign L.B. Smith, who spotted Bismarck on May 26 while piloting a British seaplane. That contact led to the German battleship’s sinking.

Roosevelt used the sinking of Bismarck to declare an “unlimited emergency.” This now meant the U.S. Navy would patrol all of the North and South Atlantic. On June 1, the South Greenland Patrol began to protect the sealanes from Cape Brewster to Cape Farewell to Upernivik. On June 7, the president approved the “Basic Joint Army and Navy Plan for Defense of Greenland,” which included a second patrol, the Northeast Greenland Patrol. The patrol went into effect on July 1, when two veteran Coast Guard ships, the Bear, built in 1874, and the Northland, built in 1926, sailed on the first patrol. Everything available was used, as Admiral King had suggested.

“Practically an Act of War”

The American Fleet complicated Germany’s only threat in the Atlantic: the U-boats. Despite Hitler’s restrictions, the Germans began to zero in on American warships. On June 20, 1941, U-203 tracked and tried to get into a firing position against the battleship USS Texas in the area of sea where the neutrality zone and Hitler’s war zone overlapped. Although U-203 failed, another U-boat sank the merchantman SS Robin Moore on June 27. But the coordination between American and British naval staffs enabled them to reroute most of the convoys from the paths of the German submarines. The rerouting worked so well that many of the U-boat sightings were only of American warships, which they were not allowed to attack. In July, the United States occupied Iceland, a European territory. This was tantamount to a declaration of war against Germany.

On July 7, the U.S. Navy landed the Marines professionally and with dispatch. Roosevelt ordered a war zone around Iceland and notified Stark and Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall that “the approach of any Axis force within 50 miles of Iceland was to be deemed conclusive evidence of hostile intention and therefore would justify an attack by the armed forces of the United States.”

Admiral King immediately followed the presidential order with “Special Instructions Concerning U.S. Navy Western Hemisphere Defense Plan No. 4—(WPL-51)” on July 25, which ordered the American Fleet to escort American merchant ships traveling to Iceland. This was later amended to include “shipping of any nationality.” The next important contingent to arrive on Iceland, on August 6, was U.S. Navy Patrol Wing 7, a contingent of seaplanes.

For the Americans, their presence in Iceland put U.S. troops and ships squarely into the Battle of the Atlantic. In short order the Americans turned Iceland into a virtually impregnable military fortress, and it became the most vital Allied outpost in the Atlantic Ocean. In his orders to King to commence the occupation, Stark wrote, “I realize that this is practically an act of war.”

U.S. Navy on Convoy Duty

As America geared up for direct convoy escort, the people at home sensed this undeclared war. In July, the president decided to put Navy plans for escorting transatlantic convoys into effect. He told Churchill this at a subsequent meeting in Newfoundland.

At that secret meeting in August, Roosevelt made several promises to Churchill, including to further project American naval strength into the North Atlantic. He forged a “concrete agreement” that committed the U.S. Navy to convoy duty. He also promised that the U.S. Navy would attack U-boats. America was at war, only Congress and the public did not know it. Back on July 29, at Senate hearings to investigate the charges that American naval vessels were convoying ships or attacking German naval vessels, the chairman of the Committee on Naval Affairs asked Knox and Stark point-blank if the Navy was escorting or planning to escort. Both flat-out lied when they emphatically said, “No.”

But American warships violated all technical definitions of neutrality by escorting convoys beginning in August. Churchill reported to the War Cabinet that Roosevelt said to him at their face-to-face meeting in August, “I would wage war, but not declare it.” Upon his return to Washington, Roosevelt went right to work to fulfill his commitments.

At the beginning of third year of the war, the British Admiralty was overwhelmed by urgent operational tasks around the world. The most demanding and difficult was the protection of Atlantic convoys, Britain’s lifeline. Amid great secrecy, important modifications in the Royal Navy’s mission took place in September. The most significant was America’s assumption of responsibility for escorting convoys on the Canada-Iceland leg of the North Atlantic run. The entry of the “neutral” American Navy into this “undeclared war” also greatly affected the deployment and operations of Canadian forces. King’s control and resources now included the entire Atlantic-based Canadian Navy. Admiral King, in consultation with the Admiralty, made substantial changes in convoy procedures in the Western Atlantic.

Roosevelt’s “Shoot on Sight” Order

On September 1, the Denmark Strait Patrol began operation. Its assignment was to close to Axis ships the entrance into the Atlantic between Iceland and Greenland while the British Home Fleet took responsibility for the other entrance between Iceland and the Faroes. Admiral King even went so far as to agree to put American ships of the Atlantic Fleet under temporary British command for the purpose of hunting down German surface ships that broke through the Denmark Strait.

On the same day, Admiral King ordered the reorganized Atlantic Fleet to begin escort duty between Newfoundland and Iceland. Naval vessels in the North Atlantic were further required specifically to operate under wartime conditions. The first American-escorted convoy was planned for September 16, but a clash between an American destroyer and a German U-boat led Roosevelt to permit American ships to fire at enemy submarines first in this undeclared war.

On September 4, German U-652 attacked the American destroyer USS Greer on a supply run to Iceland. The commander of U-652 believed he had been attacked by Greer, when actually it had been a British seaplane. Greer returned fire with depth charges. Neither ship was damaged, but the situation in the Atlantic had been shattered. A de facto war now existed between the United States and Germany.

Roosevelt used the incident to issue his “shoot on sight” order on September 11. At a conference with Hitler, Admiral Raeder analyzed the strategic implications of Roosevelt’s orders and stated, “German forces must expect offensive war measures by these American forces. There is no longer any difference between British and American ships.” The German naval staff characterized the orders as a “locally restricted declaration of war.”

Stark informed Admiral Thomas C. Hart, commander of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, in Manila, “So far as the Atlantic is concerned we are all but, if not actually, in it.”

The skirmish brought the American public into the undeclared war. After Roosevelt addressed the American people, 62 percent supported the president’s decision and America’s defense of freedom of the seas. Immediately, the Atlantic Fleet began to receive daily reports of U-boat positions in the Atlantic derived from the British Admiralty Submarine Tracking Room.

War Finally Declared

Convoy HX150, the first U.S. protected convoy, sailed on September 16. The next battle was on September 20 between the destroyer USS Truxton and a German submarine. Again neither warship was damaged. America expanded its responsibility further into the South Atlantic when, on September 29, Brazil opened two of its ports, Recife and Bahia, to American ships. By the beginning of October, the U.S. Navy was fully integrated in the two-thirds of the Atlantic Ocean that was now “American.” The U.S. Navy worked alongside the Canadian Navy escorting slow convoys along the Canadian coast. By October 1941, the Atlantic Fleet consisted of seven battleships, five cruisers, eight light cruisers, 87 destroyers, and four aircraft carriers, more carriers than in the entire Pacific.

On October 17, the destroyer USS Kearny was damaged by a torpedo off the coast of Greenland, leaving 11 dead and 24 wounded. The crew confined the flooding to the forward fire room, enabling the ship to get out of the danger zone. After power was regained in the forward fire room, Kearny steamed to Iceland. On October 31, the destroyer USS Reuben James, while escorting a convoy from Halifax, Nova Scotia, was torpedoed and sunk by U-552 near Iceland with a loss of 115 lives. She was the first U.S. warship sunk by the Germans in the Atlantic.

On November 2, to help beef up the Atlantic Fleet, Roosevelt transferred the Coast Guard to U.S. Navy command. Such action is usually initiated after a declaration of war. By November 7, Senator Robert Taft commented, “The battle of the Atlantic is now an American undertaking.” Four days later, the U.S. Navy achieved its first victory against the German Navy with the capture of the German blockade runner Odenwald off the coast of Brazil by the cruiser USS Omaha and the destroyer USS Somers. Also in November, the president ordered American troops to occupy Dutch Guiana by agreement with the Netherlands government in exile.

Within weeks, Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and Hitler’s equally surprising declaration of war carried the United States into a declared war.

America’s participation in an undeclared naval war in the Atlantic reaped enormous benefits toward its total war effort and helped carry Britain through its toughest two years. Due to secrecy, the importance of the undeclared war was not realized by the American people at the time, but its contribution to Allied victory was as important as any of the “real” war.

My father Frederick McCallum was on the HMS Rothermere which was torpedoed in the Battle of the Atlantic and I would like to know why nobody on tv or the newspaper never give any headlines of an anniversary for all the men who lost their lives.