By Kevin Mahoney

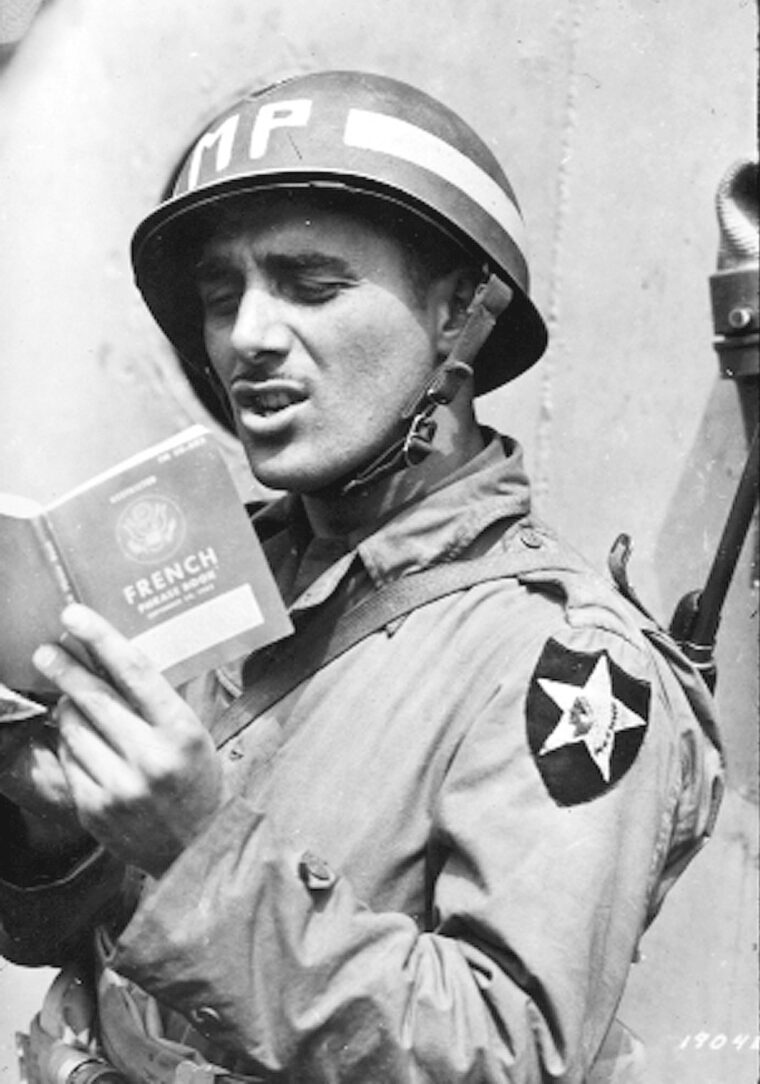

Shortly before the 101st Airborne Division parachuted into Normandy on D-day, June 6, 1944, a paratrooper wrote in his diary, “We have to sew our stripes and division insignia on both of our jump suits. We’re really hot now!” His insignia was the shoulder patch of the Screaming Eagle, a symbol of the spirit of the division that conducted the epic defense of the town of Bastogne in Belgium during the Battle of the Bulge. Like GIs in other divisions and army units, their shoulder patch was a symbol of a common identity and shared hardships to all who wore it. The shoulder patch was not, however, an innovation of World War II, but had first appeared over 20 years before, during World War I.

A system of unit sleeve insignia had developed in the British Army during World War I, intended to allow the identification of divisions, regiments and battalions in combat. As hundreds of thousands of troops arrived in France with the American Expeditionary Force in 1918, a similar system was adopted. Soldiers of the 81st Division are generally acknowledged as the first Americans to wear a shoulder patch, a wildcat sewn to their left shoulder. The AEF headquarters approved the insignia, and soon afterward those of other divisions as well, as nondivisional outfits, such as support units, in France in the fall of 1918. By the time the Doughboys began to return home in 1919, most wore a patch on their left shoulder to indicate their unit. Even some divisions that had not gone overseas during the war did so too. For the troops that had served overseas, the patch was a symbol of their wartime experience.

While representing combat in France, the insignia themselves had a particular meaning within an outfit and often included a symbol from home. The 28th Division, composed of national guardsmen from Pennsylvania, the Keystone State, chose a red keystone for its shoulder patch. Other designs combined bits of contemporary popular culture with humor. The 5th Division’s patch, a red ace of diamonds, was based on the slogan of a manufacturer of clothing dye that read, “Diamond Dye—it never runs.”

The colors and construction of these shoulder patches differed greatly between divisions and units. Many incorporated different color schemes within their basic design to differentiate regiments, battalions and other units within a division, a useful means of identification in action. But although the AEF did approve many of the designs worn by troops overseas, there was no officially approved method for their manufacture. They were made locally with the material at hand, usually of wool. Separate pieces could be appliquéd to compose the design or the design could be embroidered on the wool base. In fact, the use of wool as the base material for a shoulder patch continued until World War II.

Between the wars, shoulder patches continued to be worn by the small standing regular army, the National Guard and Army Reserve. Some new insignia were added, such as the 101st Division’s insig-nia in 1923, but the numbers were not large. Only 25 years after the “War to End All Wars” did the shoulder-sleeve insignia again become the ubiquitous symbol of the Doughboy’s direct descendant, the GI.

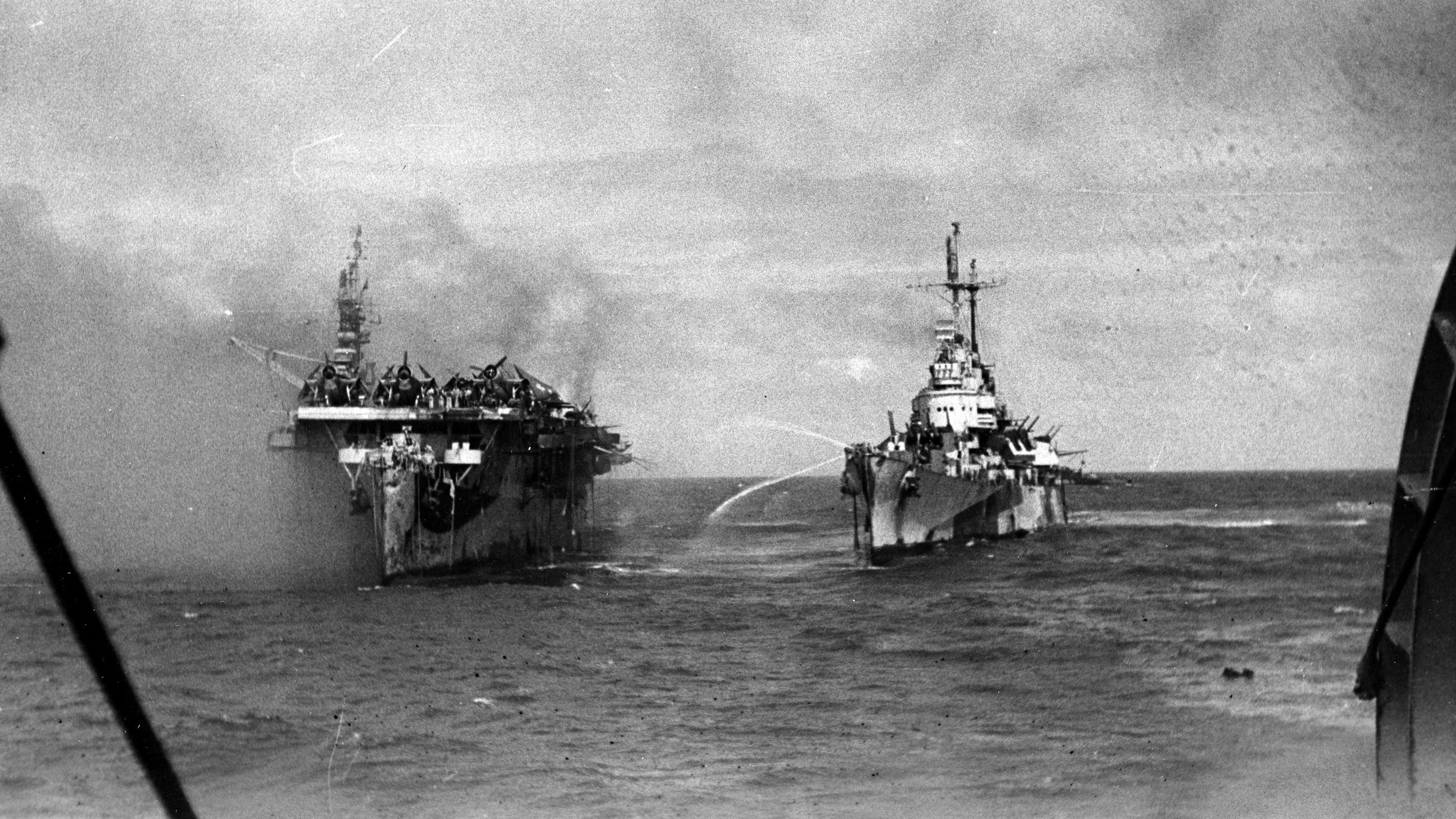

The U.S. entry into World War II in late 1941 brought about the reactivation of many of the divisions that had served in WW I, and their shoulder insignia. With the expansion of the American army ground forces into a force that eventually reached over six million men and women by 1945, a large number of new shoulder patches came into being as well; millions were made during World War II.

The Army’s Quartermaster Corps now supervised the manufacture and issue of shoulder patches, officially called “shoulder sleeve insignia,” as well as approving the designs of those that could be worn. The use of different color combinations for a given design to represent subordinate units was dropped and a single shoulder patch was now worn by all outfit members. The shoulder patch now showed a soldier’s affiliation with an army unit that could be a division of 14,000 men or a command with several hundred thousand. The army had changed since World War I and the shoulder patch with it.

The manufacturing of the shoulder patches was done by civilian contractors, working to official specifications authorized by the QM Corps. A specification for their manufacture had been written in 1937, with several revisions appearing during the war. Entitled “U.S. Army Specification No. 6-246, Insignia, Embroidered,” it described in great detail precisely what material was to be used and how the patches were to be embroidered. The thread used for World War II manufacture was generally cotton, although rayon yarn was specified for manufacture of a few patches in 1944. In later years synthetic thread was used exclusively to embroider patches. The presence of cotton thread in a shoulder patch can be confirmed to determine its vintage, many collectors believe, through the use of an ultraviolet, “black” fluorescent light. Cotton fibers do not reflect the light, while synthetic thread will, causing the patch to fluoresce or glow when viewed under black light.

Several more obvious characteristics can be used to determine if a patch is, indeed, of World War II vintage. Two varieties of the embroidered-issue type of World War II patch are found; with, or without, a narrow olive drab (OD) border. The presence of the border is usually a good sign that the patch is indeed of World War II vintage, because the practice was discontinued soon after the war. Those with an OD border are often harder to find than those without, particularly those outfits that had only limited numbers of patches made with an OD border. The patch of the 88th Division is one example; it is rarely seen with an OD border.

With or without an OD border, World War II patches were made without any “sizing” that would keep them stiff after laundering, another sign to look for in checking a patch’s vintage.

Unofficial styles of manufacture abound and make the hunt that much more interesting. A major category of unofficially manufactured patches are those made locally overseas, embroidered by hand or sewing machine, or woven. These could have been made in any theater of war with a wide variety of materials and in many different embroidery or weaving styles. Official designs are often encountered, made locally for units overseas that could not obtain the QM embroidered type because of supply difficulties. But particularly fascinating are those locally made patches with unofficial designs that, although worn by any number of army outfits, were never officially approved by the Quartermaster Corps. These can also be found in a variety of styles of embroidery or weaving.

The third major category of manufacture are bullion patches, so called because elements of the design are made of silver and gold metallic thread. These patches are usually handmade often with wool background material. Their quality is often remarkably superior to either official or unofficial embroidered patches and they can be quite striking in appearance, being worn usually on service dress uniform. These patches, like their locally made counterparts, were made all over the world (including the United States), in both official and unofficial designs. They could cost a GI a few dollars each, not an inconsequential sum in an era when a good-quality man’s shirt could be bought for $3.00. Such relative extravagance is a concrete example of the importance a shoulder patch could have for a GI.

To those “in the know,” usually other soldiers or veterans, a patch could convey participation in hard-fought campaigns without the soldier uttering a word. During the war, a regulation appeared allowing a GI to wear the patch on his right shoulder of a unit he has served with overseas. All three styles of shoulder patches, in both official and unofficial designs, were worn in this fashion. The patches that were not officially approved are often the most interesting for the collector.

Fortunately for collectors, official disapproval of an outfit’s shoulder-patch design was not an obstacle for the resourceful GI of World War II. When officialdom was too “shortsighted,” for any number of reasons, to approve a design, the shoulder would have it made locally and wear it anyway. This is indeed what occurred with the only American infantry units to fight on the continent of Asia during World War II, the 5607th Composite Unit (Provisional), known as Merrill’s Marauders, and its direct descendant, the 5332nd Provisional Brigade, or Mars Task Force. Both used the same insignia, a multicolored shield, quite striking in appearance. Official approval for the insignia was denied to both units on the grounds that regulations prevented provisional units from having their own shoulder-sleeve insignia. The men of Merrill’s Marauders and Mars Task Force had their patches made by tailors and small manufacturers in India and China, and wore them proudly. Their patch is one of the most interesting, and collectible, of the shoulder patches to come out of World War II.

Besides refusing to approve a unit’s design for a shoulder patch, the Quartermaster Corps could also order a design to be changed in the face of extreme dissatisfaction by the men ordered to wear it. Such an example is found with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the famous regiment of Japanese-Americans, or Nisei, that became one of the most highly decorated regiments in the U.S. Army during World War II. Several months after the regiment was formed in early 1943, a shoulder patch depicting a gauntleted arm, holding a sword, superimposed on a bomb blast, was approved as the regiment’s shoulder patch. Within several months the troops’ dissatisfaction with the design became so evident that manufacture of this patch was discontinued. In its place three new designs were submitted to the men of the 442nd, as the QM Corps decided that they “… would prefer to have an insignia of an inspiring nature.” The new insignia eventually chosen, the arm of Liberty holding a torch, satisfied the Nisei of the 442nd who wore their patch on the battlefields of Italy and France where they left a record of courage and sacrifice.

The wearing of the shoulder-sleeve insignia on a uniform was, of course, determined by army regulations. The patches were originally worn on service uniform jackets only. Changes in 1942 added shirts and field jackets to the list, adding 29 million patches to the eight million the army had previously estimated were needed for the year 1942 alone! When in combat, however, patches were usually, but not always, removed to prevent the enemy from using them to determine the presence of specific outfits on the front line. When troops departed for overseas from the United States they were ordered to remove their patches so their movements could be kept secret. In both cases the readily identifiable nature of a patch made such precautions necessary, but certainly made work for the GI who had to remove then replace a patch on his jacket. In the case of the 1st Cavalry Division, which used a shoulder patch about three times larger than the size of other patches, the remark was often made that the GI had his jacket sewn to the patch, rather than the reverse. Whether still on a jacket, or removed at some time, many shoulder patches eventually find their way into the hands of collectors who have created a market for patches in which prices are based on rarity, the history or mystique of the outfit, and the way it is made. Generally, officially embroidered patches are the cheapest, ranging from a dollar or two to considerably more for the rarest examples. Locally made patches sell from $5 to much more. Bullion patches are usually the most expensive, ranging in price from $25.00 into the hundreds. Like most things in life, prices go up, but rarely down. Places to purchase patches range from an antique store to patch collectors’ meetings and shows. The latter are often your best bet to either start, or add to, a collection. The American Society of Military Insignia Collectors (www.asmic.org), a national organization with a quarterly magazine, is a good place to find detailed information about shoulder patches and places to buy them. The Internet is fast becoming an excellent venue with enormous potential to satisfy collectors of all levels of sophistication.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments