By Al Hemingway

Since the 19th century, Nicaragua has been of key strategic interest to the U.S. government. Revolution regularly rocked the Central American country. The two major parties, Conservatives and Liberals, had been bitter adversaries for centuries. At the beginning of the 20th century, Jose Santos Zelaya rose to power. When Zelaya announced that he wanted to create a giant Central American republic by combining all the countries of the region into one nation, President Theodore Roosevelt intervened. He had representatives from the affected countries meet in Washington to hammer out a settlement creating a Central American Court of Justice to hear grievances. On the surface it appeared that Roosevelt’s strategy had succeeded, but Zelaya and his cohorts had no intention of following the treaty.

The “Dollar Diplomacy” of Henry Daft

Newly elected President William Howard Taft and his secretary of state, Philander Knox, devised a plan to have American diplomats abroad convince their respective countries to invest in American companies and borrow funds from U.S. banks.

The Taft brainstorm, dubbed “Dollar Diplomacy,” looked good on paper, but Nicaraguans were growing exceeding weary of their leader, Zeyala. In the fall of 1909, with backing from foreign interests, the Conservatives and aristocrats linked up and landed troops in Bluefields Province to fight Zeyala. Leading the armed force was the provincial governor, Juan Estrada, a member of Zeyala’s Liberal cabinet who had defected to the Conservatives.

Taft opted not to intervene in the civil war, but Zeyala unwisely caught and executed two American soldiers of fortune. Angered, Taft dispatched warships to the area and forced Zeyala’s resignation. Jose Madriz, the new president, continued the civil war. Rebels blockaded the port of Bluefields. Now Taft had had enough. USS Dubuque and USS Paducah, a pair of gunboats stationed just off the coast, swung into action. On May 19, 1910, landing parties from both vessels disembarked in the first of numerous American armed interventions into Nicaraguan affairs. After the American gunboats threatened to bombard the bluff where the Liberal government forces were located, Madriz’s men backed off. Meanwhile, Estrada’s rebels received U.S. aid and strengthened their position. Eventually, the Liberals disappeared and Estrada became head of the government.

A Battalion of Leathernecks in Nicaragua

In 1912, another political and military crisis erupted in Nicaragua. On May 31, a huge blast rocked Managua on the west coast, destroying Loma Fort and killing 60 people. Several days later a powder magazine was obliterated by another detonation. When new president Adolfo Diaz informed the U.S. government that he could not guarantee protection of Americans or their property, USS Annapolis steamed to Managua. At Bluefields on the eastern side, USS Tacoma dispatched a force of Marines and sailors.

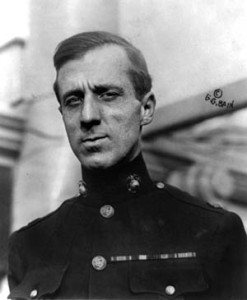

Small detachments were not enough to quell the insurgency, so it was decided to send in a larger body of troops. In mid-August, a 350-man Marine battalion docked at Corinto on the Pacific coast. Just prior to the landing, rebels had shelled the city for three days, killing nearly 1,000 people, mostly women and children. In charge of the Marine contingent was the legendary Major Smedley Butler, a hero of the Boxer Rebellion and a future Marine Corps general. Butler wasted no time pushing his way into Managua to begin negotiations to end the disturbance.

Leon, a main city that was situated halfway between Managua and Corinto, had been seized by the rebels. Butler gathered a 200-man force and set out for Leon. Butler’s troops finally cleared the line and another 750 leathernecks under Colonel Joseph Pendleton arrived to help clear the country of rebels. With the all-important city of Leon reopened to rail traffic, Butler’s battalion set out to clear the railway south of Leon to Granada, a distance of 75 miles. Although stricken with malaria, Butler maintained command and began the arduous trek to Granada via the archaic railroad.

As the slow-moving train snaked its way deeper into rebel territory, the leathernecks remained vigilant. As the cars carefully made their way through Masaya, a horseman charged in front of the train, pulled a pistol, and fired at Butler. Fortunately his aim was not good and the bullet missed Butler but struck a nearby corporal in the finger. Rebels, positioned on rooftops and doorways, raked the train with gunfire. Marines leaped from the cars onto the road and returned fire. Butler ordered the engineer to fire up the boilers and get the train moving. The leathernecks were much better marksmen than their adversaries, and soon the rebels withdrew. Five Marines were wounded and three were missing in the altercation. The rebels had 68 killed and another 60 wounded.

With Masaya in Marine hands, the battalion inched their way toward the rebel stronghold at Granada. The movement was stalled at times because sections of track had been destroyed by the Liberals. Upon reaching his destination, Butler fired off a message to rebel commander Luis Mena demanding his surrender. Knowing he could not defeat the Marines, the former minister of war capitulated.

Crushing the Insurection

With Mena and his force gone, the leathernecks concentrated their efforts on Benjamin Zeledon’s army still at La Barranca. On October 2, Butler’s battalion linked up with Pendleton’s men and, together with the Conservative army, Pendleton devised a plan to seize Zeledon’s position at Coyotepe. It was no easy task. The Liberals had managed to stockpile food and ammunition over a long period of time.

At dawn, with Butler’s Marines assaulting from the southeast and the 1st Battalion striking from the northwest, the leathernecks began their attack. Augmented by two companies of sailors from USS California, the force pushed forward to capture their objective despite the fact the government troops never materialized. Although the Liberals poured rifle fire down the hill, it proved to be largely inaccurate, and the Marines and bluejackets quickly reached the summit and, driving off its defenders, turned their own artillery on the other positions located nearby. Realizing he was defeated, Zeledon attempted to flee but was gunned down by his own men. When it was over, 27 rebels were slain and nine were taken prisoner. Seven Marines and sailors were killed.

With the insurrection squashed, the majority of U.S. forces departed the country. A small detachment of Marines were left behind to guard the American Legation in Managua. The continual presence of the leathernecks was a tremendous source of indignation to the Nicaraguan people, but in 1924 the most honest election in the nation’s history took place. During that time Marines, dressed in civilian clothes, were stationed at the polling booths to maintain order.

With relative stability established in Nicaragua, President Calvin Coolidge decided it was time to bring the Marines home. Americans who resided in the country warned the administration that newly elected president Carlos Solorzano of the Conservative Party and Vice-President Juan Sacasa of the Liberal Party would need some time to establish their government. Coolidge opted to keep the Marines there for another eight months and sent Major Calvin Carter, retired from the Philippine Constabulary, to create a program that would train selected Nicaraguans for a new National Guard that would oversee their own affairs.

Another Incursion into Nicaragua

On August 3, 1925, the Marine Guard Detachment took a train to Corinto, boarded a troop transport, and sailed for the United States. Less than a month after the leathernecks sailed from Nicaragua, a small group of Liberal cabinet members were accused of treason, arrested, and imprisoned. Conservative Emiliano Chamorro proclaimed himself the new president of Nicaragua. The United States protested the coup and refused to recognize the new government. When rioting erupted, Marines and bluejackets once again landed to ensure that American lives and interests were not at risk. As the two armies closed in around Bluefields, more than 100 infantrymen arrived from USS Galveston.

A truce was established and delegates from both parties tried to settle their issues. When the negotiations broke down, Chamorro promptly left office. Former president Adolfo Diaz returned as the interim head of state until new elections could be held. Knowing he could not defeat the Liberals, Diaz urgently asked for U.S. assistance, which was denied by Coolidge. However, when the Liberals imposed higher taxes on American businesses, began seizing their equipment, and then killed an American employee, Coolidge finally acquiesced.

Once again U.S. Marines were sent to Nicaragua. This time, however, it would not be as easy a task to rid the countryside of the insurgents. Well armed and developing better tactics, they were prepared to meet the leathernecks on the battlefield. The 2nd Brigade, led by Brig. Gen. Logan Feland, arrived on March 7, 1927. The nucleus of the brigade was the 5th Marines.

Coolidge still wanted to reach a peaceful solution. He sent Henry L. Stimson, a future cabinet secretary, to negotiate an agreement between the warring factions, the crux of which called for the joint surrender of weapons, an end to the fighting and all property taken returned to their rightful owners. Liberals would be allowed to become a part of the Diaz administration as well. While the leathernecks would stay to maintain order, a national constabulary would be created and its members trained by Marines to keep the peace when the United States finally departed.

Bandits of the West

In spite of the new armistice, guerrillas and bandits roamed the countryside at will. Most of the bandit activity took place in the country’s western region, a rugged terrain reminiscent of the American West. The provinces of Neuva Segovia, Esteli, Jinotega, and Cabo Gracias a Dios were especially troublesome. On May 16, approximately 300 bandits attacked the village of La Paz, southwest of Leon. Although outnumbered, Captain Richard Buchanan and his Marines charged the mob. Gunshots from a window killed Buchanan and another rifleman, but the Marines drove the rebels out of town.

T

en days later the Marines found the bandit leader who had masterminded the La Paz incursion. When Captain William Richards entered the dwelling, he was set upon by a woman wielding a machete. As the bandido jumped out of bed and pulled a pistol, Richards had no alternative but to kill both of them. If they had known they were confronting the best pistol shot in the Marine Corps, they might have reconsidered and surrendered peacefully.

In addition to the infantry, Marine aviation units were also sent to support the efforts to stop the insurgents. A number of DeHaviland DH-4 two-seater bombers were dispatched to Managua at an airstrip that was once an old baseball field. The aircraft flew reconnaissance flights to spot the enemy and relay information back to headquarters. By flying at low altitudes, the pilots became an inviting target to the rebels, who often fired upon the rickety planes.

On July 1, the first Nicaraguan National Guard units were assigned to Ocotal, a town situated in the northwest section of the country, near the border of Honduras. By the end of the month, they would be engaged with rebels in the area. Marine Colonel Robert Rhea and his successor, Colonel Elias Beadle, worked feverishly to train the Guardsmen prior to the 1928 elections. All Guard units were commanded by Marine officers.

Rise of the Sandinistas

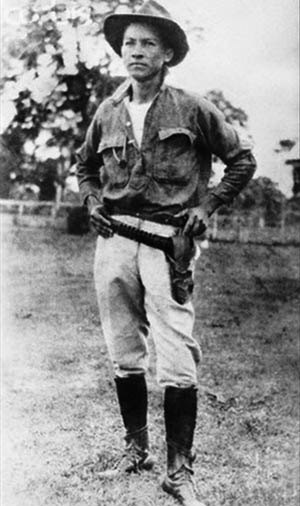

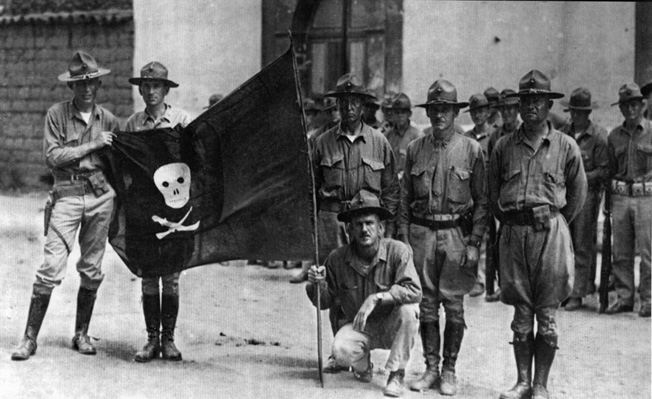

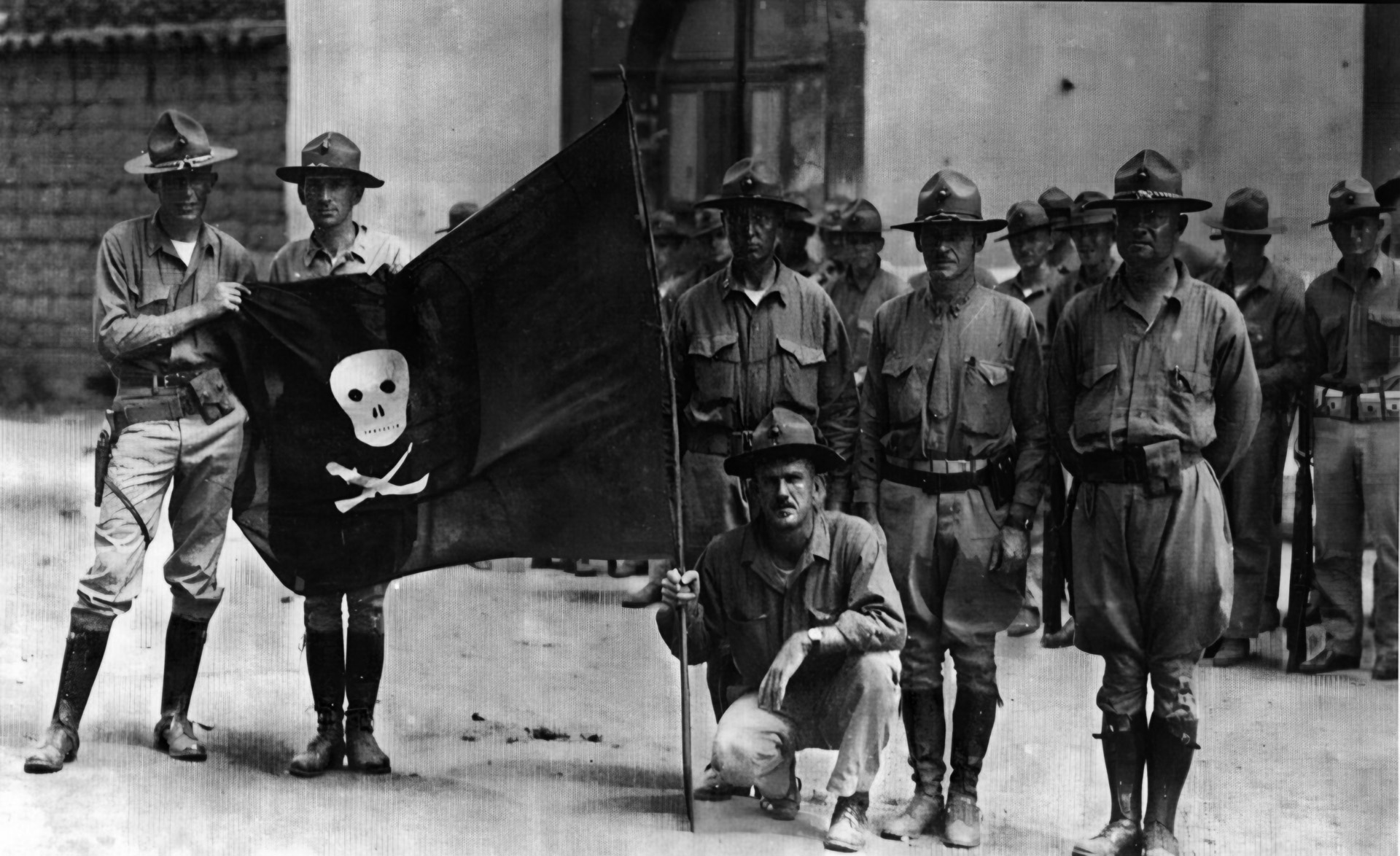

During this period the most feared of all the rebels came onto the scene. His name was Augusto Sandino. Resembling a school teacher instead of a bandit, Sandino had learned revolutionary tactics from none other than Pancho Villa when he was in Mexico. Although of slender build and not looking anything like a revolutionary zealot, Sandino would demonstrate to the Marines and Guardsmen that he was a man to be reckoned with.

With a force of 40 men calling themselves Sandinistas after their leader, Sandino linked up with rebel general Jose Moncada and immediately seized the town of Jinotega. When the Stimson-Diaz armistice was announced, Sandino refused to turn in his weapons unless the elections were controlled by the United States. The cunning Nicaraguan realized that a fair election would ensure a Liberal victory at the polls. When Stimson refused his demands, Sandino fled to the hilly, rugged northwest corner of Neuva Segovia and set up headquarters near the village of Ocotal. Here he gained support from the inhabitants and vowed to rid Nicaragua of the Conservatives and the Marines.

Major Harold Clifton Pierce led a 50-man patrol to Ocotal to find, among his other responsibilities, the elusive Sandino. Upon his arrival, he quickly diffused a situation between Liberals and Conservatives and confiscated their arms. A crude airfield was then constructed so the DeHavilands could have easy access to the area. When Pierce received intelligence that Sandino was in the area, he gathered up his patrol, with the exception of 10 Marines and some Guardsmen under Captain Gilbert Hatfield, and set out to capture the clever rebel. Since most of the residents of Ocotal were sympathetic to Sandino, Hatfield was suspicious when he saw people gathering their valuables and leaving town. He immediately had extra sentries posted and waited for the inevitable assault on his position.

In the early morning hours of July 16, a sentry spotted something in the darkness and fired. With their element of surprise gone, three companies of rebels moved into a three-pronged attack by striking City Hall and the Guardsmen’s barracks and killing any Conservatives they could locate. The Liberals had two machine-gun emplacements to cover City Hall and another nearby to fire diagonally across the plaza. When the firefight started, Guardsmen under 1st Lt. Thomas Bruce began a covering fire from the barracks with their Browning .30-caliber machine guns.

As bullets whizzed all around, Hatfield and his men raced across the plaza and joined their counterparts to fight the Sandinistas. The fighting seesawed all night and at dawn Sandino demanded that the leathernecks surrender. He thought they were low on water (which they were not) and even threatened to burn the village to the ground and watch the defenders all die a horrible death. Unmoved, Hatfield sent a curt note to the rebel commander that read: “Received your message, and say, with or without water, a Marine never surrenders. We remain here until we die or are captured.”

Several aircraft began circling the town and noticed something was amiss. Landing at the newly built airfield, Lieutenant Hayne “Cuckoo” Boyden learned from a local the severity of the situation and took off to lend his support. He and another DeHaviland pilot strafed the rebels until their ammunition ran out. By mid-afternoon, Major Ross Roswell and four other pilots were circling Ocotal. The Sandinistas found cover, expecting another strafing by machine guns, but instead Roswell’s sortie dropped bombs on their positions. The terrified rebels had never experienced a bombing run and scurried into the countryside. The Marines suffered one dead and five wounded, while 56 rebel bodies littered the area and another 100 were wounded.

Wanting revenge, Sandino set up an ambush at San Fernando to annihilate a 225-man patrol of Marines and Guardsmen headed by Major Oliver Floyd. Again, one of the Sandinista lookouts erred, allowing the leathernecks to enter the village. Floyd’s men attacked, killing 11 rebels, with Sandino himself narrowly getting away. Realizing he could not match the firepower of the Marines, Sandino decided to use the guerrilla tactics he had learned from Pancho Villa to defeat them. He took his men to the jungle stronghold of El Chipote to plan his next move.

Hunting Down the Sandinistas

For months, Marines and Guardsmen combed the northwest area around El Chipote looking for the ghost-like Sandinistas. On January 1, 1928, a patrol snaking its way along the San Albino-Quilali trail was met by a broadside of machine-gun fire and makeshift dynamite bombs. The patrol leader was wounded, but Gunnery Sergeant Edward Brown brought up a 37mm gun and pounded the rebel positions on Las Cruces Hill. As the leathernecks and Guardsmen scurried up the hill, the Liberal force ran.

Once the summit was occupied, another patrol fought its way through to reinforce the beleaguered Marines. The next morning they made a hasty withdrawal and entered the town of Quilali to await medical supplies. Sandino’s troops soon surrounded the village and the Marines and Guardsmen found themselves cut off. The only method of resupply was by air. First Lieutenant Christian Schilt volunteered to pilot a Vought O2U-1 onto a crude runway that was actually the main road through Quilali. Because the aircraft lacked brakes, Marines had to grab the wings as the plane slowly rolled down the street slowing it down so they could get their much-needed supplies. For three days, Schilt made 10 trips into the besieged town transporting 1,400 pounds of supplies. Eighteen wounded were taken back to Managua for medical treatment. For his extraordinary actions, he was awarded the Medal of Honor.

While the Marines were chasing the Sandinistas throughout the countryside, the 1928 elections were a resounding success. At more than 400 polling places, Marines and bluejackets made certain everything went smoothly. Every eligible voter had to dip a finger in red ink to ensure that they did not vote multiple times. When the 133,000 votes were finally counted, the Liberals had beaten the Conservatives by 19,000.

For the next five years, Marines and Guardsmen patrolled the rugged interior of Nicaragua, encountering the Sandinistas in numerous bloody skirmishes. In spite of the Liberal victory at the polls, Sandino did not recognize the new administration and he vowed to drive the leathernecks from his country. The Marines could not remain in Nicaragua indefinitely. The U.S. government expanded the training of the National Guard. Led by Marine officers and enlisted men assigned to the Guard as officers, the conventional units began to depart and, by 1933, they were gone.

The Marine Incursion: A Political Failure

The National Guard, formed to save the country from the rebels, eventually became its rulers. When he was given amnesty, Sandino was assassinated by the Guard in 1934 and Anastasio Somoza became president in 1936. He and his family would rule the nation with an iron hand for more than 40 years before he was ousted by, ironically, the Sandinistas.

The Marines in Nicaragua gained valuable experience in jungle fighting, expertise they would put to good use against the Japanese in World War II. Individuals such as Lewis “Chesty” Puller, “Red Mike” Edson, Evans Carlson, and Alexander “Sunny Jim” Vandegrift were educated in jungle warfare and small unit tactics that would prove to be extremely beneficial during their future island campaigns. In addition, close air support, still in its infancy, would come into its own in the years following the Nicaraguan campaigns. Pilots who had honed their skills in that country would use their knowledge well in the next war.

Politically, the Marine incursion into Nicaragua was a dismal failure. As Major W.D. Bushnell noted in American Military Intervention: A Useful Tool or a Curse: “The American military intervention in Nicaragua was unfortunate because of all the major U.S. interventions in the Caribbean area, it was the most difficult to justify. Consequently, there was good reason for its universal condemnation in Latin America and whole-hearted regret in the United States. One would be hard pressed to prove that the national interests of the United States were served by the whole sorry business.”

In line with your last paragraph, Smedley Butler, recipient of two Medals of Honor, later wrote articles about his regret that he and the Marines had been used for commercial purposes to support such companies as The United Fruit Company.

Yes, War is a Racket.