By Stephen D. Lutz

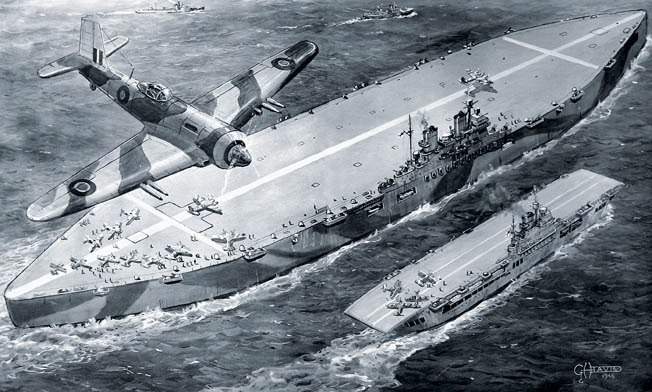

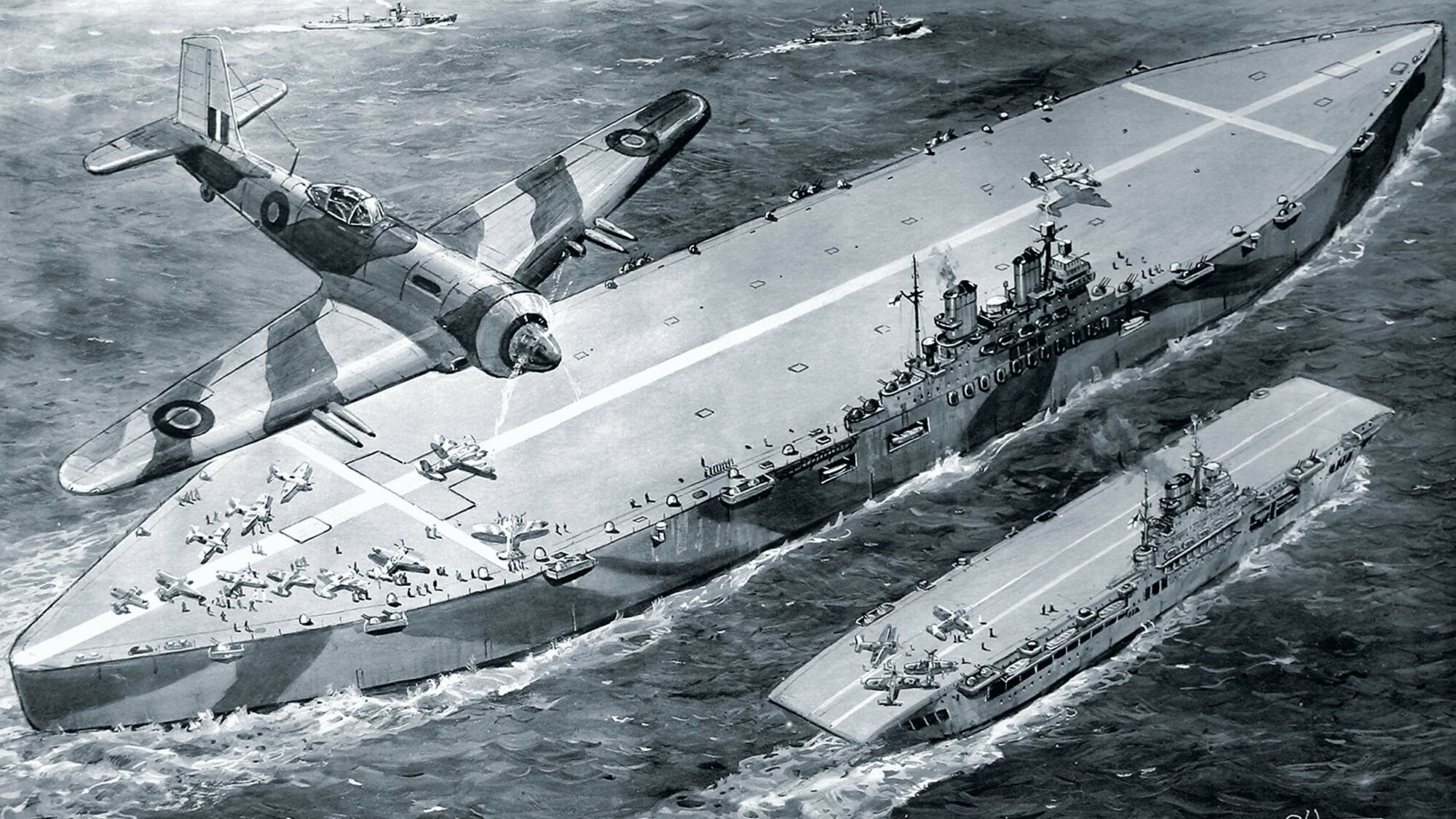

During World War II British and American aircraft carriers, serviced and ready for naval combat, averaged 20,000 to 30,000 tons. They exceeded 800 feet in length. Most of that came in steel. A quirky Englishman came up with a plan for a 2.2 million ton aircraft carrier. Her weight would have been overwhelmingly of manmade ice called pykrete. Geoffrey Pyke named his fantasy Project Habakkuk, a biblical reference to its ambitious goal: “… be utterly amazed, for I am going to do something in your days that you would not believe, even if you were told” (Habakkuk 1:5, NIV).

This quirky Englishman, perhaps best described as a cross between Albert Einstein and Howard Hughes, offered Winston Churchill his solution to stemming Nazi U-boat successes across the North Atlantic in late 1942.

Geoffrey Pyke: Darling of the Chronicle

Geoffrey Pyke was born in 1894 in the Cromwall Garden vicinity of London. At age five his 44-year-old Orthodox Jewish father died. That left him, his mother Mary, and sister Dorothy living a life of near destitution. If Mary was not previously mentally unbalanced, widowhood and near poverty may well had taken her there. Repeated episodes of unexpected, unwarranted explosive anger ruled the remaining Pyke family household. Incidents could almost be labeled as outright acts of cruelty.

As a child Geoffrey was hastened into the role of head of household. Reaching school age, he was packed off to a school dominated by sons of military officers, but his mother insisted that he maintain the family’s traditional Orthodox dress practices. That made her son a standout target for bullying. Pyke survived life at school. Dorothy took advantage of marriage and left home to never come back.

World War I began when Pyke was 21 years old. He became a foreign correspondent for London’s Daily Chronicle newspaper. Without the blessing of the Chronicle, he acquired a passport from an American merchant sailor. He got into Germany posing as a citizen of then neutral America. His plan was to canvas as much of Germany as possible to discern how its citizens viewed the war. He covered significant ground but was eventually discovered.

Considered a spy, he was sent off to a detention camp in Ruhleben six miles west of Berlin. Upon arrival he went straight into solitary confinement for 112 days. When he was released, Pyke displayed a keen talent for problem solving. Numerous escapes had been attempted at night under the noses of vigilant guards, and all had failed. Pyke took note of the compound’s layout of buildings in relation to the setting sun.

One row of buildings lay in line with it. Pyke saw that the reflecting rays nearly blinded the guards. With a German-speaking Englishman, a fellow inmate, in tow the two slinked along the outside of a row of buildings. They kept a low silhouette just beneath the windows. The guards never saw the two walk out of the compound. The two Brits made it through the Netherlands and back to England. Pyke became the darling of the Chronicle as readers read of his adventures in Germany.

The Brilliant Pyke’s Rise and Fall

In 1918, Pyke married Margaret Chubb. He became a father, took up commodities investments, and came to own one-third of the world’s tin wealth. He devised his own economic theory and practices. Many of his competitors found those practices barely moral and barely legal. Pyke, with little censoring of his opinion, saw his competition as “stupidly inept.”

Pyke would go on to renown for one smashing idiom. He could never curtail his voiced opinions of others. He always felt mentally above them. In his rawest form, Pyke could have been a peer to a disciplined, practiced intellectual giant such as Albert Einstein. At the same time, he could truly leave people marveling at the simplicity of his adaptable genius while totally alienating and offending them. His mind paused in vivid, imaginative wonderings of things to create.

One aspect of Pyke’s personality that separated him from most others was his hypergraphia. He insistently wrote on whatever scraps of paper came into his hands at any and all times of day and night. The need to write consumed his entire life. Whatever idea came to mind he committed to paper. Hypergraphia plagued him to the day he died. From paper, ideas were then worked toward some application, either practical or bizarre.

Those having known Pyke used words such as querulous, flamboyant, disorganized, eccentric, standoffish, and haughty to describe him. Pyke showed his mastery of nontraditional thinking when his son reached school age in 1926. He opened a school under his own design. Traditional teaching was shunned. Applicant teachers were hired under specific criteria. Influences of religious teachings would be prohibited from the classes. Education took on an entirely new application. Learning emphasized by practical experience minimized textbook usage.

One child found his way underneath the building. He proceeded to track the maze of plumbing pipes and electrical wiring. Upon revealing himself, his lesson became the effects of gravity upon water flow, plumbing, the structural integrity of buildings, and electricity. No disciplinary measures emerged. On the playground, seesaws had built-in hooks under the seats. Weights could be added and adjusted by the children for more exciting rides. Thus, they were introduced to fulcrum engineering. If a child had a pet that died, they were encouraged to bring the deceased animal in for dissecting to determine the cause of death. This became an anatomy class. By the end of 1928, Pyke was financially stable and productive.

The Pyke who came to formulate pykrete emerged from the disasters of the 1929 stock market crash that gave rise to the Great Depression. Pyke lost everything in the Depression. That included immediate family ties. A severe morbid depression consumed him. He moved to a hermit’s existence in Surrey, England. Personal hygiene virtually disappeared. Amid his living quarters no time was taken to clean house. He acquired bumps and bruises from colliding into furniture and tripping over trash. The single consistency remaining was his hypergraphia. If not for a mysterious, anonymous young woman hired as housekeeper and secretary, Pyke would have existed in near total isolation into the mid-1930s.

All the while, his mind kept generating simple ideas turned into complex applications. While Spain was tormented by civil war, Pyke came up with ideas to share with Spaniards fighting Nazi-supported fascism there. One was using sphagnum moss as emergency wound dressings for combat injuries. He looked at motorcycles in an entirely different light. He altered the bike’s exhaust pipe back into its sidecar. The sidecar became a heated transport container for hot meals delivered to soldiers in the field.

An Inventor in World War II

As World War II approached, Pyke recruited college students into a covert action plan against the Nazis. Pyke sent students posing as touring golf enthusiasts to tour Germany. Their ultimate goal was to evaluate how common Germans viewed Nazi policies and expectations of any outcomes if war erupted. With war declared, Pyke’s mind went into high gear. Radar was in its birth throes. It was little known and primitively used.

In the meantime, England applied a defensive line of high-altitude balloons as a deterrent to incoming enemy warplanes. Pyke suggested putting high-intensity microphone receivers in the balloons to magnify the sounds of plane engines approaching England. The notion was not taken seriously by authorities. Pyke continued on with generating ideas.

Traditional militarists saw war in three environments: land, sea, and air. Pyke saw a fourth in winter climates such as Norway, especially since the Nazis were working on components for a potential atomic bomb there.

Climates such as this required their own peculiar tactics and equipment. Pyke researched a vehicle to transport soldiers across winter terrain. It became his Operation Plough. Originally, he envisioned a contraption much like a tracked armored personnel carrier moving through snow with an engine-driven screw plowing its way along. British authorities passed the project off to the Americans. As a project consultant, Pyke visited America to see the U.S. Army develop his notion.

By the time it came to fruition, the U.S. Army had had enough of Pyke and his quirkiness. Americans found him arrogantly repulsive and offensive, in large part due to his personal appearance and hygiene. In turn, Pyke said the same of his hosts. Freely and in great detail he complained to his British superiors about American obstinance. His boss, Lord Louis Mountbatten, stepped in.

Pyke would never be invited back to America. However, Project Plough became the U.S. Army’s M-26 Weasel and was effectively used everywhere but in the snow.

Pykrete: 15% Wood Pulp, 85% Water

Other than fellow scientist acquaintances, some barely tolerating him, Pyke had one associate who consistently sided with him. That was Mountbatten. At age 41, he had become the youngest chief of staff in the British Army when named chief of command, Combined Operations. His superior officers were at least 10 years older.

Mountbatten was open to new ideas, and Pyke became the most active, imaginative mind he encountered. When Pyke was in America on his Operation Plough mission, he sent Mountbatten a 232-page memo for an upcoming project named Habakkuk. Mountbatten was sold on the idea within the first dozen pages.

Pyke’s selling point was pykrete, which may have been invented by a coworker, Max F. Perutz, born of Jewish parents in Vienna. When not excelling at biochemistry, Perutz applied equal energy to studying Alpine glaciers. He observed that the character of the ice changed when materials such as wood particles were introduced into its flow.

Perutz ended up in England working in the Combined Operations department, where he met Pyke. He shared with Pyke how simple ice could be molecularly changed by adding wood by-products to water and then freezing it. In their basement workshop beneath a London meatpacking company, the mixture was combined into a new alloy with tensile strength magnified beyond belief.

A suitable mixture of 15 percent wood pulp to 85 percent water could be poured into any mold, forming it into any desired shape and thickness. The wood by-products strengthened the ice, insulated it, and made it float better. The combination was nearly impervious to blunt trauma. Oddly, it was still susceptible to a saw blade. Stronger than concrete, the mixture was named pykrete, incorporating the name of one of its developers.

A Pykrete Aircraft Carrier

The next question revolved around what to do with the new discovery. It was decided to attempt to make a boat out of it.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had such an idea in mind already. By late 1942, Nazi U-boats ravaged Allied merchant shipping in the North Atlantic. In desperation Churchill conceived one far-fetched remedy, taking nature’s own massive icebergs and smoothing them over to make landing strips in the North Atlantic to provide air cover for convoys.

Churchill’s vision did not come about, but Mountbatten grew to appreciate Habakkuk more and more. The time arrived when he enthusiastically rushed off to share it with Churchill at his private residence. He brought along a chunk of pykrete with the thought to fill Churchill’s bathtub with hot water and see how long it took the pykrete to melt. The block of modified ice seemed to float for hours unchanged by heated water.

Churchill was awestruck. He wanted a man-made iceberg aircraft carrier 2,000 feet long, 300 feet wide, with a depth of 200 feet holding a draft of 150 feet. Its hull and bottom would measure a 40-foot thickness of pykrete. Such a vessel would supposedly be impregnable to shells and torpedoes. It was meant to withstand North Atlantic waves towering 50 feet. It would carry 200 single-engine British fighter planes as well as 100 British twin-engine bombers. The seafaring range would be nothing less than 7,000 miles doing at least seven knots.

The vessel’s infrastructure would contain a massive refrigeration system that would constantly moderate the ship’s structural temperature. Its final tonnage of ice, steel, wood, and other materials came in at 2.2 million tons. In comparison, the liner Queen Elizabeth sailed at 83,600 tons. The most fascinating aspect of it all was that the vessel could regenerate parts of itself. Even if significant surface damage was incurred, it was a simple fix. Just mix more pykrete solution and apply until frozen in place. There would be a few problems in working out cooling systems for electric motors and steering. All Churchill had to say on those facets was for the Project Habakkuk team to resolve such issues.

Churchill saw great hope for an answer to the Nazi U-boat menace. He also hoped the project would develop into a vessel capable of blockading enemy ports and into a large floating dock.

The Project Habakkuk Prototype

On August 19, 1944, during planning for Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe, Mountbatten took that opportunity to request of General Sir Alan Brooke time to present Project Habakkuk and the wonders of pykrete. Mountbatten took center stage and explained the makings of pykrete and the possibility of a 2.2 million ton iceberg aircraft carrier. He produced two square chunks of ice. One was untreated ice. The other was pykrete. He announced he would fire his pistol into each chunk.

Those in the room hurriedly lined up behind Mountbatten. One bullet fired into the regular ice block shattered and sent ice shrapnel flying around the room. Firing into the pykrete sent the bullet ricocheting across the room. One fragment went through a pants leg of an officer with no injury to him. Another spectator had a spent bullet fragment harmlessly bounce off his shoulder.

The only real injury came to U.S. Army Air Forces chief Henry “Hap” Arnold. At Mountbatten’s invitation, he took a hatchet and pounded on the pykrete. The whacks literally bounced back, jarring his arm and shoulder enough to cause a pained yelp. Other than an insignificant indention and a few scratches, the pykrete remained unscathed. Americans were somewhat impressed with the display but not thoroughly sold on Project Habakkuk, which was relocated to Canada for further research and development.

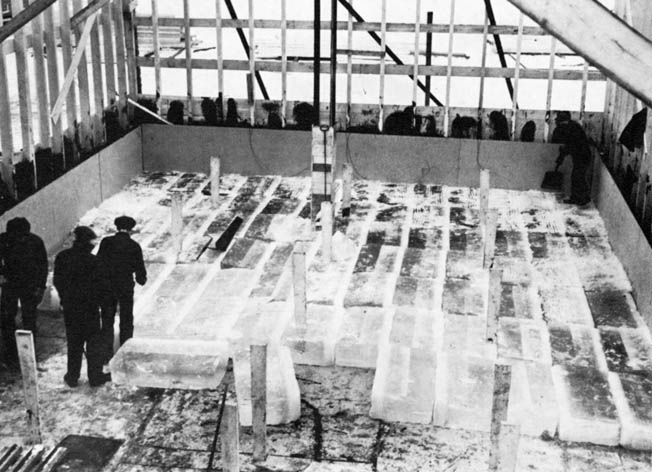

By late 1943, an eight-man Habakkuk team set up shop at Patricia Lake near Jasper, Alberta, Canada. The elevated mountainous site was removed from the hustle and bustle of crowds. A floating workshop was built on top of the lake. The wooden structure measured 60 feet long, 30 feet wide, and 20 feet high. The air conditioning system was powered by a one-horsepower engine.

It was envisioned that a completed vessel of desired measurements would require 300,000 tons of wood pulp, 25,000 tons of fireboard insulation, and at least 10,000 tons of steel. Just to see if such an object would float, a prototype was made. It came in at 60 feet long and 30 feet wide and weighing 1,000 tons, and it did float.

The End of Geoffrey Pyke and Project Habakkuk

Project Habakkuk never got any further than that. It was continually challenged by both British and American skeptics. U.S. war planners decided to save steel for traditional aircraft carriers. As with anything in its research and development phase, cost overruns plagued the effort. The success of the Normandy invasion and a reversal of fortune in the Battle of the Atlantic also doomed Project Habakkuk.

Geoffrey Pyke carried on with his grand designs, which ended up going nowhere. One of his last great visions was an elongated pneumatic tube attached to troop carrier ships to land soldiers on Japanese-held islands. That idea failed on paper.

After the war, Pyke carried on with his peculiar habits while writing, researching, and planning. It seems most of his energy was channeled into writing. On February 21, 1948, at age 54, Pyke was found dead by his landlady. The cause of death was an intentional sleeping pill overdose. He was still writing while fading away into death. The further he lapsed, the more scrawled the writing. It seemed he was approaching a topic even Albert Einstein had yet to ponder. Pyke may have been plotting a mathematical formula of the time-space continuum.

I am a model kit builder and I would LOVE to see some model company release a model kit of this!

Great article! I love information about little-known and obscure things like this. JS