By Dick Camp (Colonel, USMC, Retired)

The war in the Pacific was a bloody, protracted struggle between the Empire of Japan and the United States and her allies. The first shot that propelled the U.S. into World War II was fired in the East. Even before Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the U.S. had taken casualties in 1937 when the Japanese sank the Yangtze River gunboat USS Panay. Two U.S. sailors were killed, and a civilian passenger and 11 men were seriously wounded.

There was some concern that the incident would trigger a war. President Roosevelt sent a formal protest to Tokyo. Japan was not quite ready for war and took responsibility for the attack. They agreed to pay an indemnity of $2,214,007.36 for property loss and death/personal injury indemnification.

Once America got into a full-scale shooting war, taking back territory that Japan had conquered became a national priority nearly a full year before U.S. troops met German soldiers in ground combat. For the most part, it was the United States Marine Corps that carried out the bulk of the amphibious combat assault landings on far-flung tropical islands and engaged in a duel to the death with the Japanese occupants who did not know the meaning of the word “quit.”

By the summer of 1942, the Japanese juggernaut appeared to be unstoppable. Guam, Bataan, Corregidor, and Wake all fell to the Japanese, sending thousands of Marines into captivity. But America’s battlefield fortunes were soon to change.

Guadalcanal

Operation Watchtower, August 1942

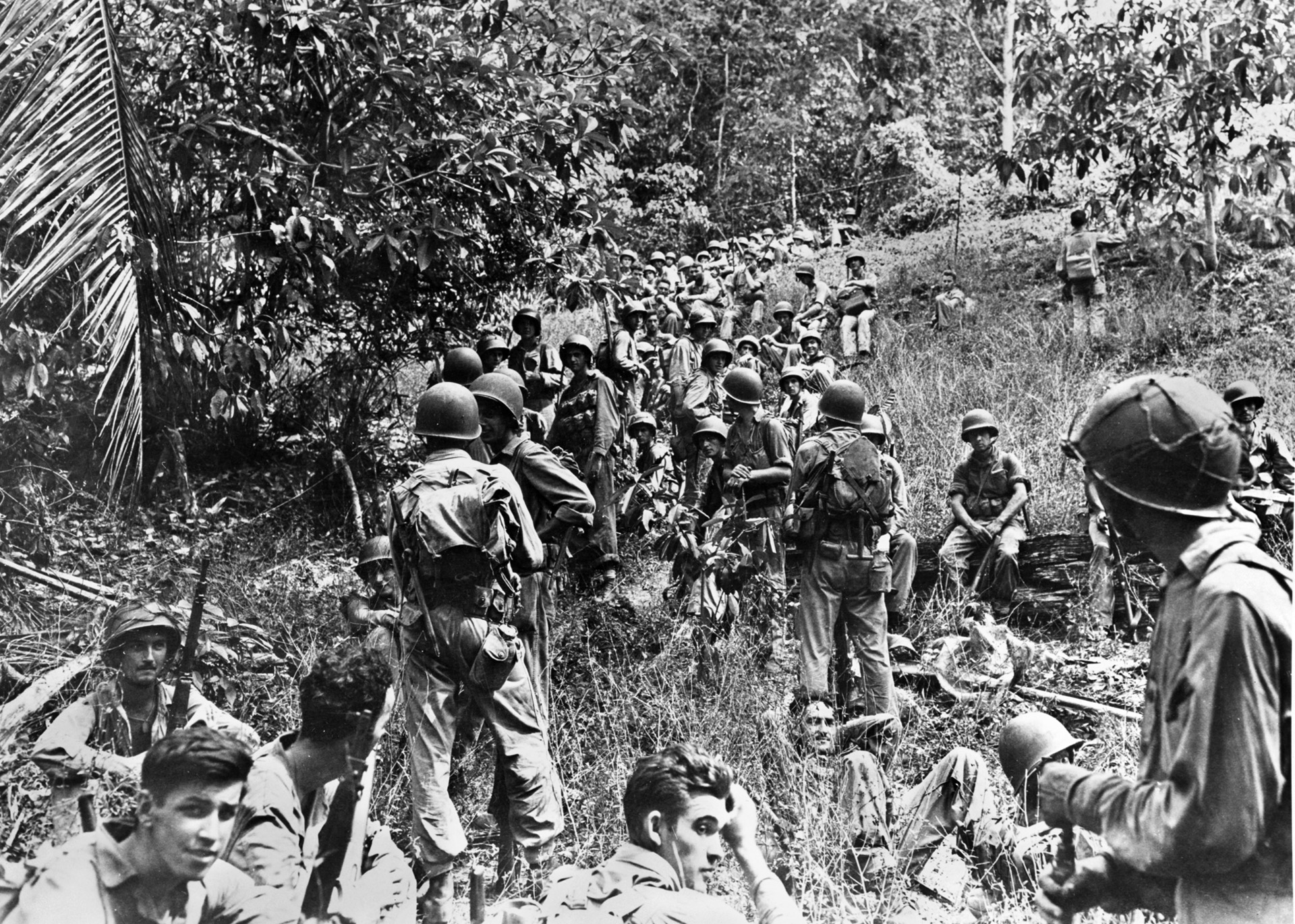

Operation Watchtower was launched to occupy and defend Guadalcanal, code-named “Cactus,” and adjacent positions (Tulagi, the Florida Islands, Gavutu, Tanambogo, and the Santa Cruz Islands) “in order to deny these areas to the enemy and to provide United States bases in preparation for further offensive action.” It was America’s first major offensive of World War II.

A 1st Marine Division colonel issued a mimeographed memo to his men. “The coming offensive in the Guadalcanal area,” he wrote, “marks the first offensive of the war against the enemy, involving ground forces of the United States. The Marines have been selected to initiate this action which will prove to be the forerunner of successive offensive actions that will end in ultimate victory for our cause. Our country expects nothing but victory from us and it shall have just that. The word ‘failure’ shall not even be considered as being in our vocabulary.”

With that, the Marines in their distinctive splotched camouflage helmet covers began climbing down cargo nets slung from the gunwales of the transport shIps and loading into landing craft that would take them to beaches that were being pounded by ships’ guns and warplanes.

On shore, Special Lieutenant (j.g.) Kakichi Yoshimoto, 3rd Kure Special Naval Landing Force (Rikusentai), was sound asleep when he was awakened abruptly by the excited voice of his batman. “Strange ships have been seen near Savo Island,” the man blurted out.

Yoshimoto hurriedly dressed and made his way in the predawn darkness to the communications station. Just as he reached the facility, bright flashes in the harbor caught his attention, followed seconds later by explosions throwing him to the ground.

“Guadalcanal was a mammoth anticlimax, devoid of combat,” wrote a U.S. war correspondent. The enemy had pulled back into the jungle after the first salvo of shells hit the beach.

“We landed pretty much unopposed,” Major Ray Davis, commanding a special-weapons battalion, recalled. “[The Japanese] had work forces there build-ing an airfield but very few armed

forces. When we landed, my weapons [Swedish-designed 20mm and 40mm Bofors automatic cannons] were still in factory crates.”

“We seized the airfield [named Henderson Field in memory of Lofton Henderson, killed at Wake Island] without opposition,” Davis explained. But the situation didn’t remain quiet for long.

“After that, the Japanese started bringing forces down to drive us off. For the next six months we were bombarded from the sea, and we were bombed from the air and attacked from the ground, but we held them off.”

“Initially, my primary mission was to provide low-altitude antiaircraft defense of Henderson Field,” Davis said. “We had a mechanical fire-control computer for the 40s. However, for anything above 4,000 feet, we had no accuracy.”

“The Japs came in at 10,000 feet the first few days and blasted us, but they learned pretty quickly when the 90mm guns started to fire. They went up to 23,000 feet … and stayed there the rest of the time.”

The Marines’ health deteriorated quickly in Guadalcanal’s tropical paradise. Hundreds of men came down with malaria and dysentery. Davis was no exception.

“We were overrun with malaria. With inadequate protection and an unbelievable mosquito population, the situation simply got out of hand. I had both types, plus a severe hepatitis jaundice attack…. Fortunately, I had a friendly surgeon who kept me out of the hospital and on my feet.”

The division’s medical log showed that in the three-month period just prior to leaving the island, 6,000 Marines were admitted to the hospital, most for malaria.

The enemy was tough, too. War correspondent Hanson W. Baldwin expressed grudging admiration for them: “Hard, ruthless, brave, well-equipped, they are the best jungle fighters in the world—judging from their operations in the Solomons and elsewhere in the Pacific…. The Japanese are never content with defense; they always try to attack…. He will keep coming until he is dead.”

The Guadalcanal campaign lasted for six months before the surviving Japanese were forced to withdraw. American losses were approximately 7,100 men, 29 ships, and 615 aircraft. The Japanese lost 31,000 men, 38 ships, and 683 aircraft. As Baldwin wrote, “Our Japanese enemies are a ruthless and very dangerous foe.” It was an assessment that would prove true everywhere.

Tulagi

Operation Ringbolt, August 1942

Operation Ringbolt, the code name given for the seizure of Tulagi Island, was part of Operation Watchtower.

In the early morning darkness of August 7, the men of the 1st Marine Raider Battalion began climbing down the cargo nets into the Higgins boats that would take them ashore. The first wave landed exactly on schedule at 8 am (H-Hour), and they landed unscathed. The landing caught the defenders by surprise.

Captain Justice M. “Jumping Joe” Chambers said, “The best beach on Tulagi was at the other end of the island, and the Japanese had clearly expected that any hostile landing would be made there.”

By late morning the Raiders had reached the main Japanese defensive positions. A green flare signalled the Japanese response. “We came under fire almost immediately,” Chambers said. Two of his men were hit by machine-gun bullets as they moved down the face of the ridge. By this time the Japanese had shaken off the effects of the air and naval gunfire and were manning fighting positions dug in on the hill.

“We thought that coconut trees would not have enough branches to conceal snipers, but we found that the Japs were small enough to hide in them easily,” Chambers recounted. “I was looking around a big coconut tree when a Jap laid a round right alongside my head.”

The Raiders continued to advance under heavy fire. “That afternoon—I’d say about 1400—we had taken the golf club house, which had been occupied by the Japs,” the battalion executive officer recalled. “We found a lot of uniforms hanging, binoculars, rice left in bowls, raw fish, and stuff like that.”

By this time it was close to dark, so the Raiders dug in for the night. All along the line, the men laid out grenades and stacked ammunition close at hand so it would be easy to reach in the dark. Machine gunners carefully sited their guns in an attempt to get overlapping bands of fire. Chambers recalled, “The password for the night contained words with the letter ‘L’ because the Japanese had difficulty pronouncing it.”

Around 11 pm a large force of Rikusentai (the Japanese Navy’s Special Landing Force, similar to U.S. Marines) struck the seam between two Raider companies, splitting them and leaving their flanks dangling in the air. One officer remembered “a series of attacks, but the real force of the counterattack hit the center of the position; this gave us the first indication of how dumb the Japs were, because the center of the position was just naturally the strongest.”

The Japanese launched two major attacks, which were beaten off. “Normally, if you make a couple of attacks and get your ass kicked and burned badly, as they did, you’d think they’d stop,” an officer reported.

By first light, the surviving Japanese had melted back into their caves and bunkers. The Raiders pounded them with mortar fire and by late afternoon declared that organized resistance on the island had ended; Tulagi was “secure.” The victory had not been without cost. Thirty-eight Raiders were killed in action and an additional 55 wounded. All but three of the estimated 350 Japanese defenders were killed.

For the rest of 1942 and well into 1943, Japanese and American forces continued to wrestle with each other in the jungles, on the seas, and in the skies for control of the Solomons. It was a bloody business, but eventually the Americans would prevail.

Tarawa

Operation Galvanic, November 1943

Two coral atolls—Tarawa and Betio—made up Operation Galvanic’s objective. Maj. Gen. Julian C. Smith, commanding the 2nd Marine Division, wrote at the start of the operation, “We are the first American troops to attack a defended atoll. What we do here will set a standard for all future operations in the Central Pacific area…. Our people back home are eagerly awaiting news of our victories.”

The amphibious tractors carrying the first wave of 2nd Marine Division’s assault troops started taking long-range machine-gun fire at 2,000 yards—and the dying began. At 800 yards, the amphibious tractors ran into the coral reef and Japanese anti-boat guns.

A coxswain lost his nerve and stopped his Higgins boat short of the reef. “This is as far as I go!” he shouted and dropped the ramp. A boatload of Marines, laden with heavy packs, stepped out into 15 feet of water; many drowned.

Shells screamed in. Tractors exploded and burned. Bodies floated in the water. Survivors stumbled out of the surf to find cover behind the five-foot coconut sea wall. The landing plan fell apart. A radioman sent a message from the beach: “Have landed. Unusually heavy opposition. Casualties 70 percent. Can’t hold!”

Two thousand badly disorganized Marines were on the beach, but in this chaos, junior officers and enlisted men took charge and led the men forward through the curtain of fire. A civilian correspondent wrote: “In those hellish hours, the heroism of the Marines, officers and enlisted men alike, was beyond belief. Time after time, they unflinchingly charged Japanese positions, ignoring the deadly fire and refusing to halt until wounded beyond human ability to carry on.”

Correspondent Richard W. Johnston detailed tank action on Red Beach and Green Beach. After crawling through deep surf, the Marine Shermans came ashore and dueled with Japanese armor. “The tanks played an all-important role. Their 75s and machine guns were a partial substitute for the Marines’ lack of artillery. [A Sherman named] China Gal outdueled a Jap tank in the course of the advance, and together two Sherman smashed in numerous pillboxes and emplacements. One of them finally was hit, caught fire, and burned.”

Operation Galvanic lasted until 1:30 pm on D+3, when the island was declared secure. Some 3,300 Marines had been killed and wounded, while the Japanese lost over 4,600. General Smith’s troops did indeed set a standard.

Roi

Operation Flintlock, Gilbert and Marshall Islands, November 1943

This combined Marine-Army operation was designed to take Kwajalein (the world’s largest atoll), the Roi-Namur Islands, and Eniwetok. Kwajalein was assigned to the 7th Infantry Division, while Roi-Namur would be the responsibility of the new 4th Marine Division.

The Japanese had installed 3,000 well-equipped defenders on Roi-Namur, but there were no underground tunnels, no underwater obstacles or mines, and the beach defenses were weak. After two days of continuous air and naval bombardment, the 23rd Marines assaulted Roi while the 24th Marines hit Namur.

The assault on Roi was making good progress, but there were still enemy strongpoints to be eliminated. One large, reinforced-concrete blockhouse with walls three feet thick stood in the path of the 2nd Battalion, 23rd Marines. It had been partially damaged by naval gunfire, but the battalion commander, Lt. Col. Edward J. Dillon, ordered Company G to make sure it was completely demolished.

A 75mm half-track fired five rounds against the steel door. Under covering fire, a demolition squad came up and placed satchel charges at the gun ports and shoved Bangalore torpedoes through a shell hole in the roof. The squad pulled the igniters and ran like hell for cover. There was a terrific explosion; twenty Marines were killed and dozens wounded. Falling debris killed several men who were caught in the open, and even men in small boats a considerable distance from the beach were killed and wounded. An observation pilot radioed, “The whole damn island has blown up!”

Large chunks of concrete, torpedo warheads, and bombs were blasted high into the air. An eyewitness described an ink-black darkness spreading over a large part of the island. Where the large blockhouse had been, now all that remained was a large, water-filled crater. The demolition squad had not realized the blockhouse had been a torpedo-warhead magazine.

As the Marines were trying to recover from the explosion, two more concrete bunkers exploded, apparently set off by the Japanese. The cumulative effect of the three explosions caused 50 percent of one landing team’s total casualties for the operation.

Despite the disaster, the Marines managed to secure Roi within 48 hours at a cost of 195 killed and 545 wounded; the enemy had 3,472 killed and 91 men captured.

Saipan

Operation Forager, June 1944

Forager was a three-island campaign—Saipan, Guam, and Tinian. Saipan’s importance lay in its planned use as the first B-29 base in the Pacific. Three days of intense naval and air bombardments softened up the island for the 2nd and 4th Marine Division’s invasion.

The 4th MarDiv’s landing beaches, color-coded Blue 1, Blue 2 (23rd Marines Regimental Combat Team), Yellow 1 and Yellow 2 (25th Marines Regimental Combat Team), were located on the lower-west coast of Saipan, adjacent to the 2nd MarDiv’s landing beaches: Green 1 and 2 (8th Marines Regimental Combat Team) and Red 1 and 2 (6th Marines Regimental Combat Team).

The first wave consisted of 68 armored amphibians, armed with 37mm and 75mm guns, formed in line abreast. Behind them surged 196 troop-carrying amphibious tractors in four successive waves spaced from two to six minutes apart. The first wave approached the fringing reef in good order.

Robert E. Wollin recounted, “We got no Japanese fire outside the reef. Moving over the reef I saw small colored flags sticking out of the water. The Japs drove in aiming stakes overnight for their artillery waiting for us to come into range. Then all hell broke loose.” Mortars, small arms, and artillery fire increased in intensity.

Jerry D. Brooks recalled, “In the lagoon, hitting coral heads, bouncing us up, down, and sideways, it was impossible to shoot our 75mm howitzer with accuracy. A couple of our 75mm shells exploded directly in front of us. Two or three went nearly vertical … but our noise and the sight of us alone apparently made a big impression on the enemy. Naval operators monitoring Jap radio traffic picked up their messages telling Tokyo that ‘monster guns’ mounted on ‘monster floating tanks’ were coming at them in the leading assault waves. Our 75mm’s muzzle with blast shield looked like an 8-inch gun.”

“Nearing the beach I saw a watery explosion, then another and another,” Winton W. Carter recalled. “Ahead, slightly to my left, two men got up and started running inland. I stared. Paralyzed. I tried to grasp what this meant. They wore steel helmets, short sleeve shirts. ‘They’re Japanese, you Lummox, the enemy, shoot!’ It seemed ages. But probably two or three seconds actually passed until my brain and hands got to working together. Then I opened up with my machine gun, firing away.”

Wollin recalled, “Jap artillery was still bracketing us, trying to get our range, and drenching us with near-misses, splashing water into open turret hatches. Still, they were misses. We were lucky. As the Japs sharpened their range, the assault wave coming in behind us looked to be having the harder time.”

Lt. Gen. Holland “Howlin’ Mad” Smith remarked, “Saipan instantly became a savage battle of annihilation … spearheaded by armored amphibian tractors…The Marines hit the beach at 0843 … the best we could do was get a toehold and hang on. And this is what we did, just hang on for the first critical day.”

M. Neil Mumford described coming ashore: “I saw out the side hatch an amtank afire next to us, its hatch going up and down. I thought someone was trying to get out, but the heat was moving the hatch, making it flutter; then the tank’s ammo began to blow. A shell hit the base of our turret. We abandoned our tank, only to discover it was safer inside.”

The leading waves of troops landed and debarked short of the O-1 line, the first day’s objective. “Someone shouted, ‘The American army’s coming!” a Japanese soldier wrote. “I lifted my head a little. They advanced like a swarm of grasshoppers. The American soldiers were all soaked…they were so tiny wading ashore. I saw flames shooting up from American tanks, hit by Japanese fire.”

Long-range grazing fire from enemy machine guns pelted the beaches, pinning the Marines to a shallow beachhead. 1st Lt. John C. Chapin recalled, “All around us was the chaotic debris of bitter combat. Jap and Marine bodies lying in mangled and grotesque positions; blasted and burnt-out pillboxes, the burning wrecks of LVTs that had been knocked out by Jap high-velocity fire; the acrid smell of high explosives; the shattered trees; and the churned-up sand littered with discarded equipment … suddenly, WHAM! A shell hit right on top of us!

“I was too surprised to think, but instinctively all of us hit the deck and began to spread out. Then the shells really began to pour down on us: ahead, behind, on both sides, and right in our midst. They would come rocketing down with a freight-train roar and then explode with a deafening cataclysm that is beyond description.”

One officer recalled, “It’s hard to dig a hole when you’re lying on your stomach digging with your chin, your elbows, your knees, and your toes [but] it is possible to dig a hole that way, I found.”

The assault companies found themselves fighting for every inch. “Our attention [was] concentrated on our yard-by-yard advance inland—our beachhead was only a dozen yards deep at one point,” Holland Smith said.

Time-Life journalist Robert Sherrod wrote, “An artillery or mortar shell…landed every three seconds for the first 20 minutes. Most of them were in the water, 100 yards and more offshore, but some of them hit the beach itself. None of them hit inside the seven-foot deep [tank] trap which the Japs had built for their protection and which we were now using for our protection. Inside the trap the battalion aid station for 2/8 (Lt. Col. H. P. Crowe) had been set up. There were a half dozen men lying on the sand; they were already bloodily bandaged and awaiting evacuation by amtracs…. In the 300 yards separating two [wrecked] vehicles I counted 17 dead Marines…”

Captain John A. MacGruder spotted “a young, fair-haired private who had only recently arrived as a replacement, full of exuberance at finally being a full-fledged Marine on the battle front. As I looked down at [his body], I saw something I shall never forget. Sticking from his back trouser pocket was a yellow pocket edition of a book he had evidently been reading in his spare moments. Only the title was visible—Our Hearts Were Young and Gay.”

Casualties sustained during the landing far exceeded 2,000; in the 2nd Division alone, 553 men were killed and 1,022 wounded. Out of the 68 armored amphibians, 31 were sunk or disabled. Five of the original infantry battalion commanders in the two divisions were wounded on D-day. Howlin’ Mad said, “Not for another three days could it be said that we had ‘secured’ our beachhead. We were under terrific pressure all the time.”

Guam

Operation Forager, June 1944

Colonel E.A. Craig said, “As I was walking along the road which cut through Asan Point ridge with Captain George Percy and a runner, I was surprised to look to my left and saw two Japanese soldiers who had just come out of a cave. One of them raised a square package in his hand and threw it at me. It landed some distance away and exploded with a terrific roar, knocking me off the road and into a ditch filled with sharp stones. It was a so-called satchel charge.

“Several Marines in the area came running up, firing at the Japs as they went back into the cave. A jeep with an anti-tank gun arrived at this time and it was trained into the cave and blasted away for some time. Many dead Japanese were later found in this cave, which ran some distance back in the hill to other positions. I was severely bruised from the concussion. It really made my teeth chatter for a while.”

Craig was closely following the advance of his men when they “heard the sound of motors starting. Before we could locate the position of the noise, two enemy tanks rolled out of cleverly camouflaged positions on the side of the hill off to our right and headed toward us firing machine guns and small-caliber cannons. They were not over 100 feet away, and I had visions of losing all my men who were in the immediate vicinity.

“A bazooka man and his assistant went into action immediately. With a calmness that was uncanny, they proceeded to knock out the tanks in quick succession!”

A couple of gutsy Marines jumped on the tanks, forced open the hatches, and dropped hand grenades inside, finishing the crews. “We later found two well-camouflaged, unmanned tanks dug into the side of the hill, just a short distance away,” Craig said.

The battle for Guam cost 3,000 American lives.

Peleliu

Operation Stalemate, September 1944

The Battle of Peleliu occurred between September and November 1944 on the island of Peleliu (today Palau) and involved over 18,000 men of the 1st Marine Division and the Army’s 81st Infantry Division against 11,000 Japanese.

Oily black smoke rose into the sky, marking a funeral pyre of more than 20 burning amphibious tractors off Peleliu’s White Beach 1 and 2. Major Raymond Davis’ 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, plowed through the shell bursts.

“Mortar shells began falling all around the LVTs; the Japs had apparently sited their heavy weapons to cover the area between the reef and the shore,” Davis said. “Three tractors of our wave were hit going in, with great loss of life, and the fires we had seen raging on the beach turned out to be numerous LVTs and DUKWs.

“When I got off the amphibian tractor on the beach, my run for cover was not quick enough; a mortar round splashed nearby and ran a long sliver into my knee. It bled a lot, but they got it out, doctored me up, and I went back to work.

“The lead elements were bogged down on the beach,” Davis recalled, “and the men had to fight their way off the beach.”

The battalion after-action report stated, “Company A moved into positions trying to take advantage of a Jap anti-tank ditch. It was apparent that the Japs had sited anti-tank weapons from the left flank and mortars from the ridges to the front to cover this ditch well, and his riflemen and mortars made the ground untenable. It is only natural that our Marines, lying in all the attitudes of death, should have sought shelter in this defiladed trench.”

The company was stopped cold; casualties were severe. Davis recalled, “The enemy had tunneled back under the coral ridge lines, sometimes 100 to 200 feet, and they would lay a machine gun to shoot out of a distant hole, with deadly crossfire from well dug-in and fight-to-the-death defensive positions.”

The Japanese counterattacked and cut off a squad. “Sergeant [Robert W.] Riley noticed two amphibious tractors and a Sherman tank that had been knocked out on his left,” the after-action report noted. “He ordered his men to form a skirmish line to the right of the tank … took its machine gun and brought fire to bear, inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy and pinning them down.

“The squad was rescued when the company executive officer sent out another tank. Upon Riley’s return, he was elevated to platoon commander after all its leaders had either been killed or wounded. Riley led the 2nd Platoon through some of the fiercest fighting of the campaign until wounded by grenade fragments. The platoon was turned over to the ranking Marine, Pfc. G.E. Hogan.

“While Sgt. Riley and his men were occupied with the Japs in their sector, Sgt. Aubertin with the 2nd Squad of the 1st Platoon under command of Cpl. McQuade succeeded in storming the coral ridge to their front and moved down the other side. They contacted Company I on their right and refused the left flank, bending it back to the ridge behind them. Since there was a distance of 200 yards to cover, Sgt. Aubertin organized four separate fire groups, with visual contact, and successfully held the ground he had taken until noon the following day. During the night they repulsed all efforts of the Japs to dislodge them.”

With Company A pinned down, Company B was committed to the attack but suffered the same fate. Corporal Herbert B. Goff “boldly faced the withering barrage in a determined effort to outflank the Japanese opposing troops and, skillfully disposing his men for maximum effectiveness, fearlessly led them in a determined attack,” as recounted in his Navy Cross citation.

“Aware that the fire of his squad was insufficient to neutralize the heavily fortified emplacement, he pressed forward alone and, armed only with grenades and a sub-machine gun, succeeded in silencing the hostile weapon and annihilating the crew before he was fatally struck down by enemy fire.” His effort was not enough, and Company B was forced to go to ground.

A historian wrote, “The battle remains one of the war’s most controversial, due to its high death toll, but questionable strategic value. Considering the number of men involved, Peleliu had the highest casualty rate of any battle in the Pacific War.” Eight Medals of Honor were awarded. Over 2,330 Americans died and 8,450 were wounded. Only 202 Japanese survived.

Afterwards, many analysts said that the isolated island should have been bypassed and allowed to “wither on the vine,” rather than be the scene of such carnage.

Iwo Jima

Operation Detachment, February 1945

Author S.E. Smith wrote, “If Peleliu was formidable, then certainly Iwo was beyond belief. It was, in point of fact, the greatest fortress encountered by the Marine Corps in World War II.” Lt. Gen. Holland Smith called Iwo “the most savage and costly battle in the history of the Marine Corps.”

What importance did this “ugly, smelly glob of cold lava squatting in a surly sea,” as William Manchester put it, have in the overall conduct of the war in the Pacific? And why did three Marine divisions (3rd, 4th, and 5th) need to assault it?

Korean slave laborers had spent years constructing miles of tunnels, gun emplacements, pillboxes, bunkers, underground supply depots, command posts, hospitals, and living quarters. There were also three airfields (one under construction) that would be perfect as bases for bombing Japan.

Trying to dismantle all that hard work were six battleships and five cruisers, smothering the island with 14,000 rounds of 14-inch and 8-inch shells—the heaviest naval bombardment up to that point of the war.

Seven Higgins boats (LCPR, or Landing Craft Personnel, Ramped) carrying Marines of the Provisional Reconnaissance Unit and sailors from Underwater Demolitions Teams (UDT 12, 13, 14 and 15) bobbed up and down in the slight ocean swell. Their big diesel engines idled as the coxswains waited for the signal to make their run. The signal came and the coxswains hit the throttles, and with a roar of engines, the boats surged forward.

Corporal Charles A. “Art” Linder, a scout/sniper in the 5th Reconnaissance Company, Headquarters Battalion, Fifth Marine Division, studied the shoreline. “It was difficult to see because we were so low in the water, but I could make out the silhouette of the beach and the terraces that led upward from the water’s edge,” he said.

The forbidding profile of the 550-foot Mount Suribachi (code-named “Hot Rocks) loomed over the landing beaches. “As we got closer,” Linder recalled, “I saw one big explosion on the side of the mountain where a large-caliber naval shell hit. I also saw several caves, which I assumed contained Japanese guns.”

Linder’s boat passed between two camouflage-painted LCI(G)s, converted infantry landing craft, as the craft prepared to support the swimmers with rockets, 20mm, and 40mm gunfire.

Thirty thousand Marines were coming ashore. At first there was no hostile greeting, and then the defenders opened up with heavy mortar and large-caliber artillery fire, turning the black lava sand blood-red. Within minutes, the lightly armored LCI (G)s were in trouble; nine of 12 were put out of action, and three were damaged.

The Marines and UDT swimmers were in serious trouble. Their support had been shot to pieces, and they were all alone, within spitting distance of the Japanese guns. Linder saw “bullet splashes in the water, particularly when we went in as close as 150 meters. We started evasive action to avoid fire.”

War correspondent Richard Newcomb wrote that a sergeant “and a corporal ran to the first pillbox. They threw in three or four grenades, and the corporal ran inside. He came out with his bayonet dripping blood, trotted to a second pillbox, and jumped on top of it. Fire from another pillbox killed him.”

At 8 am on the 23rd, a combat patrol from Company E, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines, seized the crest of Suribachi and raised a small American flag. Another larger flag was sent to replace it.

Joe Rosenthal, an Associated Press stringer, related his account of the second flag raising to the author: Joe said that he heard that a patrol was going to the top of Suribachi, so he tagged along. When he got to the top, he saw several Marines tying a flag onto an iron water pipe. Being only five-feet-five inches tall, he stacked up several stones to stand on. He held his camera about waist high when he heard someone shout, “There she goes.”

Joe quickly swung the camera up and snapped the photo. “Out of the corner of my eye, I had seen the men start the flag up. I swung my camera and shot the scene. That is how the picture was taken, and when you take a picture like that, you don’t come away saying you got a great shot. You don’t know.” Later, he shipped the film to the military press center in Guam to have it developed. The photograph of the flag raising immediately became a sensation.

When Rosenthal reached Guam some days later, he was asked if the shot had been posed. He thought they were referring to a group photo of the men after the second flag raising and said “yes.” Once he saw the famous photo, he corrected his acknowledgement, but the rumor persisted that the photo was posed. “I don’t think it is in me to do much more of this sort of thing…. I don’t know how to get across to anybody what 50 years of constant repetition means.”

The flag raising, unfortunately, did not symbolize the end of the battle. Beating Iwo Jima into submission took nearly three months and cost the lives of 6,821 Marines; over 19,000 others were wounded. Few Japanese survived.

Okinawa

Operation Iceberg, April 1945

Sheets of flame lit the pre-dawn darkness as the naval guns of battleships, cruisers, and destroyers of Task Force 58 pounded the Hagushi Beaches in preparation for the landing of thousands of Marines and soldiers of the Tenth Army.

At 7:45 am on April 1, waves of carrier planes swept over the island, bombing and strafing known or suspected targets. With the thunderous cacophony of light and sound as a backdrop, Vice Adm. Richard K. Turner, Commander Joint Expeditionary Force (TF-51), gave the traditional order: “Land the landing force.”

The transport areas were alive with activity as the Marines and soldiers of the assault force began to debark. Hundreds of landing craft stood alongside the transports, waiting for the troops to climb down cargo nets. LSTs (Landing Ship Tank) disgorged fully loaded amphibious tractors. Tank-carrying LCMs (Landing Craft, Mechanized) floated from the well decks of LSDs (Landing Ship, Dock).

An eyewitness described the scene: “The water was a turmoil of movement: dispatch and control boats running about, LCMs and LSTs moving slowly forward to their unloading areas, motor torpedo boats dashing around as guides…”

The 1,400 landing craft formed into waves behind the line of departure, marked by control boats lying off each landing beach. Major Charles S. Nicholas, Jr., USMC, and Henry I. Shaw, Jr., described the assault in Okinawa, Victory in the Pacific: “At 0800 the pennants fluttering from the masts of the control craft were hauled down, signaling the first wave of LVT (A)’s [armored amphibian tractors] forward behind a line of support craft.

“In its wake, hundreds of troop-carrying LVTs [amphibian tractors] disposed in five to seven waves crossed the line of departure at regular intervals and swept toward shore. One Japanese soldier observing the huge armada bearing down on him wrote in his diary, ‘It’s like a frog meeting a snake and waiting for the snake to eat him.’”

Colonel Hiromichi Yahara, Senior Staff Officer, 32nd Army, wrote in The Battle of Okinawa, “At this time the commanders of Japan’s 32nd Army are standing on the crest of Mount Shuri near the southern end of Okinawa’s main island, quietly observing the movements of the American 10th Army…. The group simply gazes out over the enemy’s frantic deployment, some of the officer’s joking, a few casually lighting cigarettes…. For months now the Japanese army has been building its strongest fortification on the heights of Mount Shuri—and its adjacent hills.” [Lt. Gen. Mitsuri] Ushijima [commanding general of the 32nd Army] marveled at the “earthshaking bombardment, vast and oddly magnificent in its effect.”

Gunboats led the assault waves in, firing rockets, mortars, and 40mm guns into prearranged target squares on such a scale that all the landing area for 1,000 yards inland was blanketed with enough explosives to average 25 rounds per 100-yard square. The pre-H-Hour bombardment was the heaviest concentration of naval gunfire ever to support a landing: 44,825 rounds of 5-inch or larger, 33,000 rockets, and 22,500 mortar shells.

After approaching the reef, the gunboats turned aside and the amphibious tanks and tractors passed through them and proceeded toward the beach. First Marine Division Special Action Report, Okinawa, noted, “First waves were on all beaches at 0839, with air observation reporting no damage to landing craft in the initial waves. First reports from assault elements of the division reported very light resistance with all units moving rapidly inland.”

The first waves went ashore “standing up,” a cakewalk. The landing was virtually unopposed. Journalist Robert Sherrod wrote after reaching the beach, “I’ve already lived longer than I thought I would.”

At noon on L-Day, Admiral Turner reported, “Preceded by intense naval and air bombardment, troops of Tenth Army began landing Hagushi beaches at 0830. Troops landed on all beaches against light opposition. Practically no fire against boats, none against ships…” The troops were amazed and overjoyed; intelligence had predicted casualty rates could reach 80-85 percent. Within the first hour, the Tenth Army put 16,000 combat troops ashore.

Yahara wrote, “Contrary to their expectations, the enemy meets no resistance from Japanese troops. They will complete their landing unchallenged … they are not suspicious that the Japanese army has withdrawn and concealed itself in the heights surrounding Kadena [Mount Shuri], with plans to draw the Americans into a trap.”

But it was the Japanese who were trapped—as many as 100,000 died. When the 82-day battle had ended, total American dead on Okinawa ranged between 14,000 and 20,000. But the war had been brought to Japan’s doorstep and was nearly over.

America’s “Island Hopping” strategy to seize key bases in the Central Pacific was made possible by the Marine Corps’ and Navy’s development of amphibious tactics two decades before the outbreak of World War II. During that time, the Marine Corps established itself as specialists in amphibious warfare, which was the key to success in the Central Pacific and resulted in the final defeat of Japan.