By William E. Welsh

Chicago native Private John J. Kelly of the 78th Company of the 6th Marine Regiment and another soldier requested permission from First Lieutenant James M. Sellers on the eve of the U.S. infantry assault at Blanc Mont Ridge to reconnoiter the German position. Having received authorization, the two men crept cautiously towards the German’s frontline trench. When they received no fire, they continued directly toward the channel. Finding it unoccupied, they reported their findings to their superior officer.

The intelligence was vital to the attack of the U.S. 2nd Infantry Division scheduled for dawn on October 3, 1918. Instead of squandering precious time attacking an empty trench line, the Americans took advantage of the intelligence to move forward to the abandoned trenches during the daylight hours on October 2. They used the captured trenches as the jump-off point for their attack the following morning.

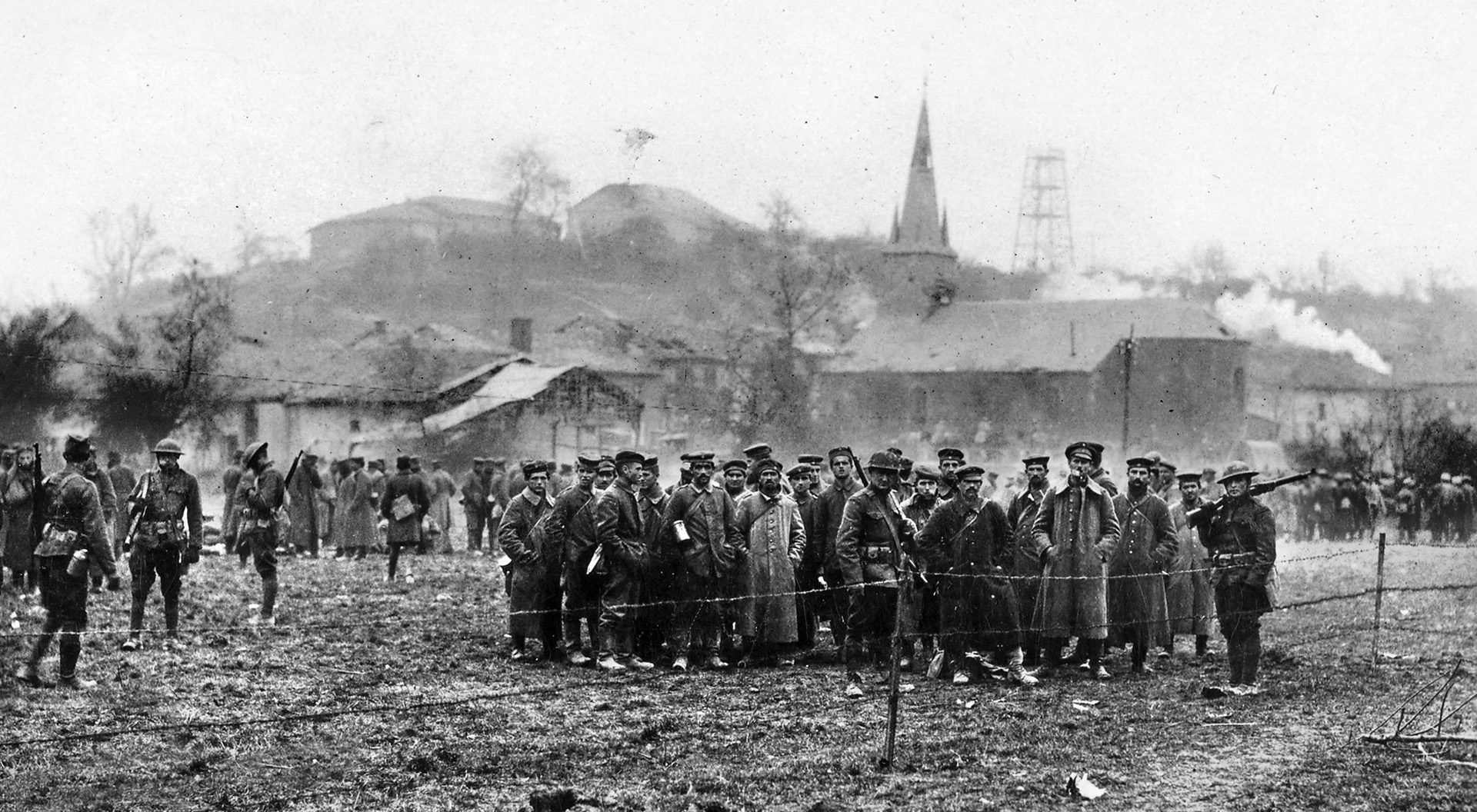

When the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, it initially seemed as if the U.S. Marines would be sidelined and not allowed to join the American Expeditionary Force. American General John Joseph “Black Jack” Pershing initially had no intention of having the Marines serve in France. However, Secretary of War Newton Baker and Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels ultimately persuaded Pershing to allow the Marines to fight in France. Pershing’s intent was to have Americans units fight together rather than parceling them out as reinforcements to front-line French and British armies. Despite this stance, Pershing did loan some units to the French in order for the American troops to gain vital combat experience.

The 5th Marine Regiment arrived in France with the first wave of U.S. troops in June 1917. They were followed eight months later by the 6th Marine Regiment and the 6th Marine Machine Gun Battalion, both of which arrived in France in February 1918. Pershing formed these three regiments into the 4th Marine Brigade, initially under the command of Brig. Gen. Wendell Neville. Pershing then created the 2nd U.S. Infantry division in October 1917 by combining the 4th Marine Brigade and the 3rd Army Brigade. He tasked Marine Corps Maj. Gen. John Lejeune with leading the division into battle.

Private John Kelly was destined for great feats of battle fighting in the ranks of the 4th Marine Brigade. He enlisted in the Corps at the age of 18 on May 15, 1917, in Port Royal, South Carolina. After successfully completing boot camp at Paris Island, he was assigned in mid-September 1917 to the 78th company. His courage under fire would earn him multiple citations for valor, including the nation’s most prestigious military decoration, before the war was over.

Like other Marines, Kelly received combat training that included bayonet use, hand-grenade throwing, unit tactics, and, most importantly, marksmanship training with the 1903 Springfield Rifle. Of the 73,000 Marine Corps officers and men recruited and trained during World War I, 24,500 served on the Western Front.

The 2nd U.S. Infantry Division’s baptism of fire occurred in late May and June at Chateau Thierry and Belleau Wood. After the soldiers of the 3rd Brigade checked the Germans at the crossings of the Marne River, the 4th Marines battled with the Boche throughout July. The Marines not only repulsed repeated assaults, but their important victory over the Germans at Belleau Wood earned them the praise and admiration of the French.

After gaining a foothold in Belleau Wood, the Marines launched six separate attacks in late June that drove the Germans out of the strategic tract of forest. During this phase of the battle, the Marines showed themselves more than willing to engage in bloody hand-to-hand combat with rifle butts, bayonets, and knives. The Americans continued assisting the French in the hard fighting that continued around at Chateau Thierry in mid-July.

The Allied attack against the German salient at St. Mihiel that began on September 12 afforded Pershing the first opportunity to deploy the full weight of the AEF in France against the Germans. He organized his forces into two super-sized corps, each of which contained four divisions. The Allies caught the Germans off guard as they were withdrawing in late July from the salient to avoid being encircled. Pershing’s attack was a resounding success; the Allies took possession of the salient after just four days.

General Henri Gouraud, the French Fourth Army commander, requested American reinforcements in mid-September for an attack he was scheduled to launch in the Champagne Region. The goal of the attack was to push back German forces that were threatening the Allied supply hub at Reims. Another objective was to drive the Germans from Blanc Mont Ridge. Pershing agreed on September 23 to loan the 2nd U.S. Infantry Division to Gouraud.

Lejeune participated in the careful planning undertaken for the assault on the formidable German positions atop the limestone ridge west of the Aisne River. Gourard informed Lejeune that his division would be attacking across a two-mile front. The American commander received permission for his two brigades to attack side-by-side in battalion columns.

Marine tactics called for tight coordination between supporting artillery units and the advancing infantry units. In accordance with previously developed tactics, Lejeune’s lead battalions had orders to follow closely behind the rolling artillery barrage in an effort to catch the Germans before they had fully emerged from their dugouts.

The German frontline units experienced severe manpower shortages as a result of heavy casualties from their Spring Offensive. The few replacements they could scare up were either boys or old men who lacked adequate training. The Germans compensated for a shortage of riflemen by distributing more light and heavy machine guns to the front-line troops to offset the shortage of riflemen.

The German 51st and 200th infantry divisions defended the ridgeline. The Germans deployed their green machine-gun teams in scattered positions in front of the ridge, while the veteran machine gunners deployed in the main trenches and bunkers.

The Germans had established an impressive defense-in-depth consisting of four main lines of resistance stretching from Mont Blanc Ridge east to the Aisne River. The Germans put few resources into holding the forward trenches that constituted the first line of defense. Instead, they concentrated on building up the fortifications atop the ridge, where they had established their second line of defense. The German infantry had painstakingly constructed sturdy dugouts and bunkers that took full advantage of the natural rock atop the ridge.

The Germans had held Mont Blanc Ridge since 1914. Repeated attempts by the French to pry them out of their positions had failed. If the Americans could force the Germans to retreat from the ridge, the Germans likely would have to withdraw 30 miles to the Aisne line. The Americans moved into the positions from which they would step off to attack on October 1. In the process, they replaced the exhausted French 61st Infantry Division. The 4th Marine Brigade deployed on the left, and the 3rd Army Brigade took up positions on the right. Within the Marine brigade, the 6th Marine Regiment would lead the attack, and the 5th Marine Regiment would follow behind it.

The French divisions deployed on each side of the U.S. 2nd Infantry Division had orders to advance simultaneously with the Americans. Gourard had scheduled the attack for October 2, but poor communications among the French and the American units compelled Fourth Army headquarters to postpone the attack until October 3.

In preparation for the attack, the 4th Marine Brigade arrayed itself in a column of battalions with the 2nd Battalion in front, the 1st Battalion in the middle, and 3rd Battalion bringing up the rear. The first two battalions into action each had the support of 12 French tanks, and all three battalions had the support of a machine-gun company.

One of the most challenging parts of the attack for the 4th Marine Brigade would be containing the German troops on their left flank, who were strongly entrenched in a fortified zone bristling with machine guns known as the Essen Hook. The 6th Marines would have to advance two miles over ground dotted with scrub and small trees that afforded the attacking infantry scant cover. The French 21st Division on the Marines’ left flank was entrusted with neutralizing the Essen Hook.

During World War I runners carried communications back and forth on the battlefield because neither radio nor telephone communications existed on the tactical level. Private Kelly served as one of these military couriers. Even though his principal duty was carrying messages, he also served as a scout and participated in combat as needed.

By the time of the Battle of Blanc Mont Ridge, Kelly had proven himself to be a brave Marine who was cool-headed under fire. He had earned four Silver Stars between July and September in combat at Château-Thierry and St. Mihiel. This means he held the Silver Star with four bronze oak-leaf clusters.

The Marine attack on Blanc Mont Ridge began at 5:50 am on October 3. After an initial five-minute barrage, the lead units stepped off. They fought their way steadily up the slopes towards the crest behind a rolling artillery barrage. As anticipated, the Germans in the Essen Hook poured heavy machine gun fire into the left flank of the advancing Marines. The Americans were mortified that the troops of the French 21st Division did not attack the Essen Hook as directed.

At 6:20 am Kelly sprinted 100 yards ahead of his company towards the German positions. He ran straight through the Allied artillery barrage to attack a German machine-gun nest. He hurled a grenade at the machine-gun nest, killing the gunner, and then shot a surviving member of the machine-gun crew with his pistol. He then rounded up eight prisoners and returned with them through the artillery barrage. When he saw his fellow Marines, Kelly greeted them with a matter-of-fact pronouncement. “Just what I told you I’d do,” he shouted.

Kelly received two Medals of Honor for his valor at Blanc Mont Ridge. He received one from the Army and another from the Navy, which made him a double recipient. He was one of only 19 double recipients ever to receive the Medal of Honor. Kelly’s act of valor went “beyond the call of duty in action,” stated his Navy citation.

Three hours into their attack, the Americans were halfway to their objective. When the French failed to assault the Essen Hook, additional Marines were directed to return fire against it. Later in the day, the Marines stormed the crest of Blanc Mont Ridge. They succeeded in piercing the German line at five points. The Germans launched an unsuccessful counterattack characterized by bloody hand-to-hand fighting that night in a desperate bid to retake the ridge. The scene was ghastly on the morning of October 4. “The trenches were choked with days-old bodies, often dismembered, which were turning green under the sun during the day and molding at night,” recalled Captain Wendell Westover of the 4th Machine Gun Battalion.

Pershing pinned the two Medals of Honor on Kelly while he was serving with the Army of Occupation at the Koblenz Bridgehead. In addition to his Silver Star with four oak leaf clusters, he received the World War I Victory Medal with five bronze battle stars. His foreign commendations were the French Médaille Militaire and the Croix de Guerre 1914-1918 with bronze palm and bronze star for valorous service during the war. He also received from Italy the Croce al Merito di Guerra and from Montenegro the Silver Medal for Bravery.

Kelly, who was discharged from the Army in August 1919, passed away in his Illinois hometown at the age of 59 in 1957.