By Jon Diamond

Today, Bukit Timah, meaning “Tin Hill” in Malay, is a residential and business neighborhood in the center of the island of Singapore approximately seven and one-half miles northwest of Singapore City.

On Upper Bukit Timah Road, directly opposite Bukit Timah Hill to the east, stands a commemorative World War II museum on the site of the old Ford Motor Factory. With the factory’s remnant façade still present, the museum is replete with relics, photographs, personal testimonies, and exhibits that historically recount the gruesome fighting and atrocious occupation of this island nation by the Japanese.

In 1942, the 600-foot Bukit Timah Hill, the highest elevation on the island, commanded the surrounding vicinity, which included large depots of Allied fuel, foodstuffs, and ammunition in addition to being proximate to the Peirce and MacRitchie Reservoirs that provided the one million citizens of Singapore City with their water supply.

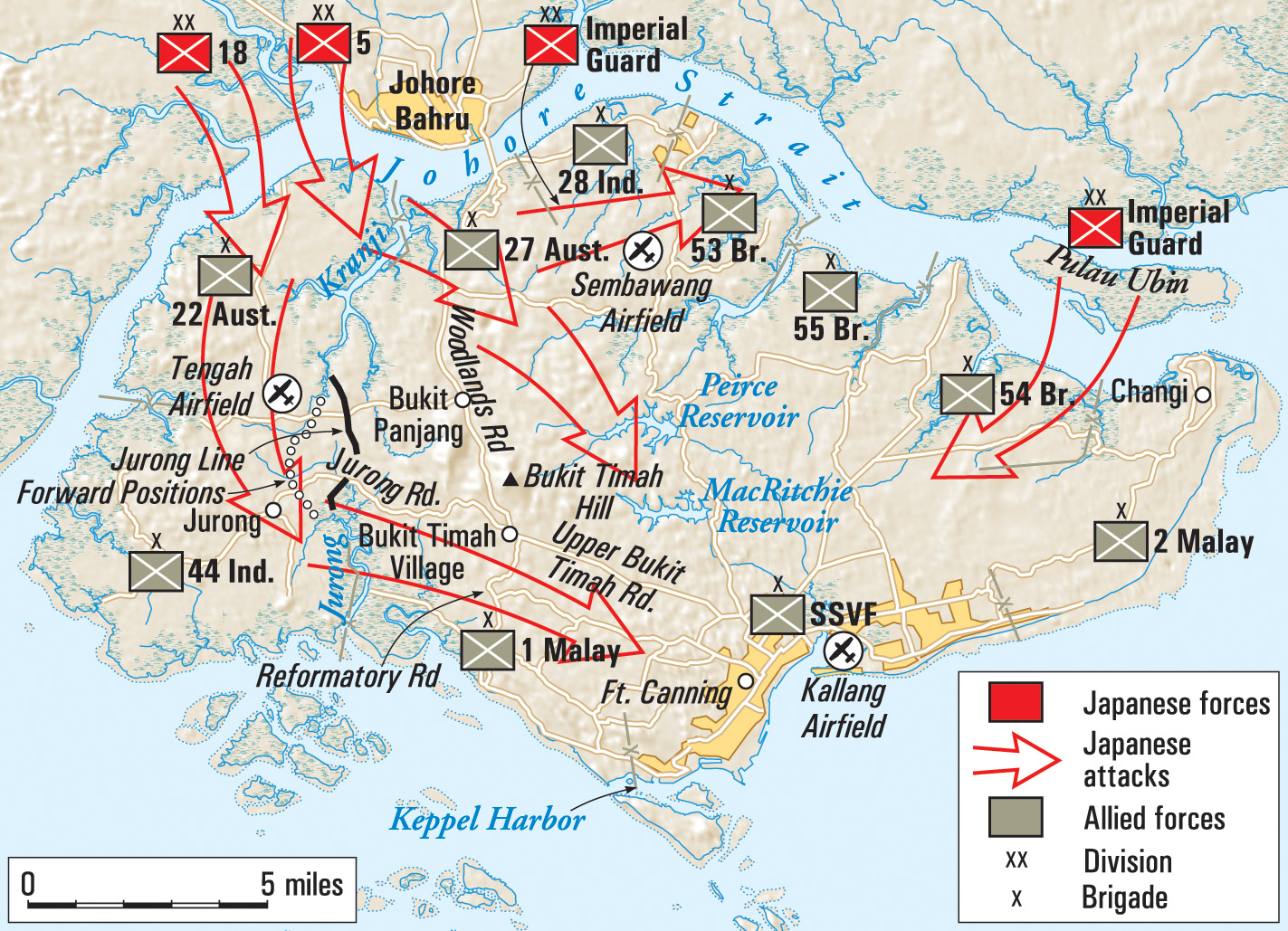

A theme that there were actually two battles at this locale is carried throughout the museum. The first battle, on February 10-11, 1942, was in the general Bukit Timah area as the 5th and 18th Divisions of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) seized both Bukit Timah Hill and Village and repelled a fairly large-scale Allied counterattack late on February 11. The second was a noncombatant verbal “battle of wits and bluff” between Lieutenant General Tomoyuki Yamashita, commander of the Japanese 25th Army, and British Lieutenant General Arthur E. Percival, General Officer Commanding (GOC), Singapore, which was centered at the Ford Motor Company’s conference table during the surrender negotiations on February 15. In both “battles” at Bukit Timah, the invading Japanese overwhelmed the Allied defenders.

After the lightning Japanese conquest of the Malay Peninsula from December 8, 1941, to January 31, 1942, Yamashita’s main invasion of Singapore Island occurred in strength on February 8, when the IJA 5th and 18th Divisions began crossing the Straits of Johore onto the northwest side of the island, where the British high command had not expected them to land. The late-evening amphibious assault in small boats and landing craft was preceded by massive Japanese artillery and airstrikes against the Australian 22nd Brigade in the Western Area zone. After suffering heavy casualties in the initial landing waves, the Japanese were able to consolidate their beachhead, since the frontage that the solitary Australian brigade had to cover was too extensive.

The next Allied defeat at the so-called Jurong Line served as a prelude to the combat at Bukit Timah. The Jurong Line was a gap that ran along a minor ridge between the sources of the Kranji and Jurong Rivers. The 22nd Brigade began to fall back onto the Jurong Line after Percival ordered the destruction of the oil tanks near the demolished causeway that spanned the Straits on the night of February 9. The Jurong Line’s positions were not fortified, but they provided the Allied troops reasonable fields of fire for machine and anti-tank guns. Additionally, the line was relatively short at roughly three miles and strongly manned by the retreating Australian 22nd along with the Indian 12th, 15th, and 44th Brigades.

Four Allied brigades seemed sufficient on paper to defend this improvised position. However, the Allies defending both Malaya and Singapore lacked tanks, constituting a monumental tactical-planning error. There were large dumps of food and fuel between the Jurong Line and Bukit Timah village, which Percival had to ensure did not fall into Japanese hands. Furthermore, the MacRitchie and Peirce Reservoirs, which were vital for Singapore City’s water supply, were just to the northeast of Bukit Timah.

Field Marshal Archibald P. Wavell, head of the several-week-old, Java-based American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM), which was responsible for Singapore’s defense, visited the island for the last time on the afternoon of February 10. The situation was so tenuous on Singapore that the headquarters building of the Western Area Command, in which Wavell, Percival, and Australian Lieutenant General H.G. Bennett, met was shelled. There, the Allied triumvirate learned that the entire Jurong Line had been abandoned, not entirely due to casualties suffered by combat against the advancing IJA 5th and 25th Divisions, but mostly because of a succession of confused and anxious subordinate brigade commanders withdrawing on their own volition. The only defensive position before Bukit Timah was now open to the enemy.

Wavell ordered Bennett to mount a counterattack with the remaining elements of the four Allied brigades to recover the Jurong Line positions at the earliest opportunity. However, no counterattack was launched against the Japanese due to Allied casualties and exhaustion. Instead, Percival made the strategic error of withdrawing further inland toward Singapore City. After less than two days of fighting, nearly one-third of Singapore Island was under Japanese control. Also, major components of Yamashita’s 5th and 25th Divisions were nearing Bukit Timah Village.

Yamashita surmised that Bukit Timah Hill would be the next Allied defensive position and wanted an immediate attack before the Allies could reorganize after their recent setbacks of February 8-10. On the evening of February 10, the 5th Division had regrouped with some tanks around Tengah Airfield, west of Bukit Timah. At the same time, the 18th Division was on the Jurong Road, about three miles west of Bukit Timah. Both formations were ready to advance onto Bukit Timah Hill. From there, Japanese heavy artillery could eventually shell Singapore City, and infantry could move onto the reservoir catchment area. Japanese seizure of the Bukit Timah area would also compel the Allied garrison to abandon a large part of Singapore Island’s fuel, food, and munitions depots.

As Japanese artillery ammunition was dwindling and with the heavier ordnance still on the other side of the straits, Yamashita ordered a nighttime bayonet attack for February 10-11 on Bukit Timah Hill with the 5th Division advancing east along the Choa Chu Kang Road and the 18th Division simultaneously moving down the Jurong Road. The Japanese commander anticipated a desperate struggle for this strategic location; however, confusion among the Allied troops and an absence of fixed defensive fortifications led to the rapid loss of the heights to the enemy.

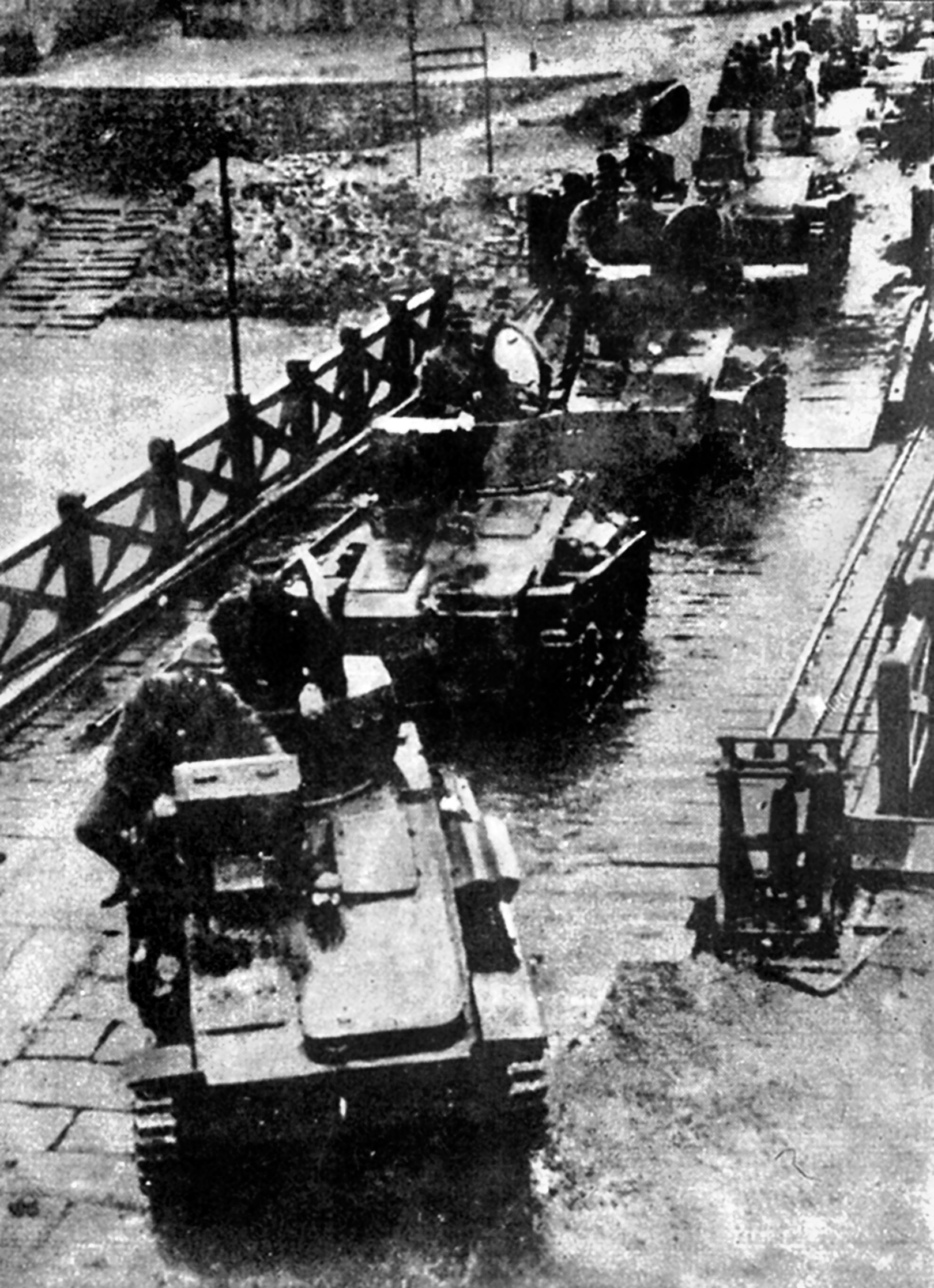

The battleworthy Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders fought valiantly to maintain control of Bukit Timah Hill and the adjacent supply depots but could not resist the column of 50 Japanese 5th Division tanks advancing south from Bukit Panjang. The hastily constructed British defensive works were quickly swept away. Elements of the 12th Indian Brigade came under infantry and tank assaults as well as an accompanying mortar attack after dusk on February 10. A few Japanese tanks were disabled as the Indians withdrew to high ground about 200 yards east of Bukit Panjang near the Woodlands Road. The Australians similarly withdrew later that night. The Japanese infantry and armored column continued to move south down the Woodlands Road, entering Bukit Timah Village and halting there at 1:00 am on February 11.

Australian troops trying to regain lost ground came under heavy Japanese machine-gun fire and infiltration as they took up positions near the Jurong Road and saw Bukit Timah Village ablaze in the distance. These Aussies of X Battalion, an ad hoc unit of 550 men, were almost annihilated by the Japanese in the predawn hours of February 11. Others from the 2/19th and 2/20th Battalions of the 22nd Brigade barely escaped Japanese infantry attacks. Unfortunately, a fuel depot east of Bukit Timah had been set ablaze and silhouetted the Australian positions.

Other British troops and elements of the Indian 15th Brigade attempted to reach Bukit Timah during the early hours of February 11, but they took heavy casualties from Japanese machine-gun and mortar fire near a low area called Sleepy Valley. These Indian troops of the 15th Brigade broke up into smaller formations and withdrew to the south near Reformatory Road.

After the rout of major elements of the 12th and 15th Indian and the Australian 22nd Brigades, all that immediately separated the Japanese from Bukit Timah and Singapore City were a few British and Australian artillery and anti-tank guns and crews. After receiving news of the seizure of Bukit Timah Hill and Village at dawn of February 11, Yamashita ordered both his 5th and 25th Divisions to advance east toward the Upper Peirce and MacRitchie Reservoirs to strike the flank of an anticipated Allied counterattack on Bukit Timah that was expected to come up the Bukit Timah Road.

Early on the morning of February 11, Percival, with Wavell’s encouragement, directed his subordinates to assemble a brigade-sized unit of British 18th Division troops, called Tomforce, to retake both Bukit Timah Village and Bukit Timah Hill. Tomforce, under Lieutenant Colonel Lionel Thomas, had the dubious mission to attack Japanese tanks and infantry with only some armored cars and Bren carriers. The ad hoc brigade comprised the 18th Division’s Reconnaissance Unit, the 4th Norfolks of the 54th Brigade, 1/5th Sherwood Foresters from the 55th Brigade and a battery of 2-pounder anti-tank guns. Most of these British troops had been shipwrecked the week before on their voyage to Singapore.

Tomforce moved up the Bukit Timah Road toward Bukit Timah Hill across a 2,000-yard front, encountering many retreating British, Australian and Indian troops. Tomforce was subjected to Japanese ground-support airstrikes from land-based, twin-engined bombers of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN), as well as heavy Japanese infantry fire. Yamashita had taken Tomforce’s move seriously, having diverted the IJN bombers from Keppel Harbor in the south to attack the British infantry.

Tomforce’s assault eventually ground to a halt without much of a chance of dislodging the Japanese from Bukit Timah. By nightfall, surviving members of this unit along with some supporting Australians withdrew under difficult circumstances with Japanese infantry in pursuit.

Percival decided not to order any further counterattacks to regain Bukit Timah, choosing to gather his remaining forces around Singapore City in a 28-mile perimeter with Keppel Harbor to the southwest and Kallang Airfield at the northeastern end. Space to maneuver for Percival and his troops continued to dissipate as the Japanese now occupied almost half the island. Nevertheless, the Allies continued an intense field-artillery bombardment of Japanese positions in and around Bukit Timah.

As February 11 was also the anniversary of the coronation of the Emperor Jimmu, the legendary first emperor of Japan, Yamashita had decided to airdrop a request for surrender to Percival warning him about the potential harm that could come to the civilian population of Singapore City should an all-out assault become necessary. Yamashita also sent a signal to Imperial General Headquarters: “The Japanese Army, having stormed and captured Bukit Timah heights, has advised the surrender of Singapore city upon which we look down.”

There were reasons why Yamashita seemed rash in continually pushing his attacks on Singapore without reestablishing his logistical lifeline. Yamashita was appointed commander of the 25th Army on November 5, 1941. Although respected by many of his peers, the newly-installed Prime Minister Hideki Tojo was a political enemy. Another enemy was his immediate superior, General Hisaichi Terauchi, commander of the Southern Army.

When Yamashita was relieved of command of Japanese forces in Manchuko in northern China and given command of the 25th Army, poised to invade Malaya and Singapore, he was well aware of his perilous political position and the need to achieve a quick, decisive victory that would protect him from demotion, further disfavor from Tojo and Terauchi, or even worse.

Further, Yamashita had already received a signal from Imperial Headquarters with potentially ominous implications. It read, “On 15 February an officer attached to the Court of the Emperor will be dispatched to the battlefield. We can postpone the visit if the progress of your Army’s operations makes it desirable to do so. We wish to hear your opinion.”

Opinions varied among Yamashita’s staff officers as whether to accept the timing of the Imperial envoy’s visit or postpone it as Allied resistance had seemed to stiffen. To avoid dishonor with Tokyo, Yamashita signaled back, “On the 15th day of February the enemy will positively surrender to the power of the august Emperor.” Now, the so-called “Tiger of Malaya” had made a firm temporal commitment to the Emperor for the Allied surrender; he would have to get Percival to agree to terms by February 15.

Unfortunately for Percival and his defenders, by February 13, the Japanese controlled the island’s entire reservoir catchment area. Fears began to circulate that a major epidemic would ensue without fresh water. The capture of the depots at Bukit Timah had reduced the island’s reserve supplies to under a week. Deserters, refugees, and looters roamed the environs of Singapore City. Percival, apparently not sensing any panic in the city’s perimeter yet, refused to reply to Yamashita’s surrender request of February 11. Both Prime Minister Winston Churchill and General Wavell cabled Percival on February 13 that he must mount a vigorous defense. Churchill’s message read in part, “The battle must be fought to the bitter end at all costs….”

By the evening of February 14, Japanese repairs to the previously demolished causeway spanning the straits had been completed. Soon the whole of the 25th Army was concentrated on Singapore Island. Japanese heavy artillery rapidly moved to positions on the heights near the reservoirs. Despite the Allied withdrawal to Singapore City after the loss of Bukit Timah, Colonel Masanobu Tsuji, the mastermind and chief planner of the Japanese offensive, had made an unsettling observation that the British were expending their field artillery shells as if they had no shortage while Yamashita’s artillery ammunition stockpiles were running dangerously low.

Perhaps the chiding comments from Wavell and Churchill prompted Percival to defend the island to the last. Regardless, Japanese staff officers noted that the withdrawing Allied forces were putting up a more tenacious fight as Japanese tanks were halted just south of Bukit Timah.

Some Japanese officers were also concerned that if the British held out for several more days, they would win the battle, since Yamashita’s ammunition supply was dwindling. Japanese field-artillery units had to limit their counter-battery fire on Allied guns since they were down to less than 100 rounds per gun and even fewer for heavier pieces. Yamashita’s supply system was virtually drained, and he was informed that if fighting continued for another 72 hours his forces would be placed in an impossible logistical situation.

A few Japanese officers had the audacity to suggest calling off the assault and returning to the Malayan mainland for resupply and refitting. By 4:00 pm on February 14, Yamashita wondered whether the British shelling indicated that they intended to fight for Singapore street by street, house by house. With the Japanese troops also nearing exhaustion, suddenly the prize almost within their grasp was possibly out of reach. Some Japanese officers were wondering if they, in fact, might be the ones to surrender.

Like his naval counterpart, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, who was widely known to be an excellent bluffer at the poker table, Yamashita launched into a bluff of his own. He would expend artillery shells as if his supply was unlimited to convince Percival that British and Commonwealth forces had no alternative but to capitulate. Military deception can sometimes become an added force for a commander willing to employ it at the right time and place.

By February 15, just 48 hours after the martial exhortations of Churchill and Wavell, Percival had a change of heart. He now sensed a crisis for the civilian and military forces of Singapore City since the Japanese truly did threaten a drought with its attendant consequences for the city’s population.

Despite complete Japanese control of the Peirce and MacRitchie Reservoirs, water was still flowing to Singapore City’s pumping stations. However, only two water-pumping stations were operating, as Japanese artillery had destroyed many of the water mains and pipes. Further, the advancing Japanese were now within a few hundred yards of one of these pumping stations. At the Fort Canning Reservoir, the water had dropped from 12 to two million gallons in a single day with complete drainage anticipated within hours.

On February 15, Percival cabled Wavell for permission to surrender, stating that further resistance and loss of life would be futile, anticipating his defense not lasting beyond another 48 hours. Wavell, from ABDA headquarters in Java, refused and urged the island’s defenders, “You must continue to inflict maximum losses on enemy for as long as possible by house-to-house fighting if necessary. Your action in tying down enemy may have vital influence in other theatres. Fully appreciate your situation but continued action essential.”

After meeting with his military commanders on the morning of February 15, Percival decided to surrender despite a personal message from Churchill to Wavell calling for a last stand by the numerically superior Allied forces. Percival cabled Wavell that he would ask for a cease-fire that afternoon. Wavell acquiesced and now gave permission for the surrender if there was nothing more to be done.

Percival had no fuel for any vehicles; he had nearly exhausted his field-artillery ammunition; and there would be no water in a matter of hours in a city with a million inhabitants living in an equatorial climate. Food reserves were limited to 48 hours since the depots at Bukit Timah had been captured on February 11. For Percival, a personally brave man, capitulation was a bitter step. He chose to go himself, if called for by the Japanese, in the hope of obtaining better treatment for his troops and the population.

Yamashita’s chicanery in utilizing his remaining artillery ammunition at Allied positions was successful. At 11:00 am on February 15, Japanese lookouts saw through the trees along the Bukit Timah Road a white flag hoisted atop the broadcasting studios. One of Yamashita’s staff officers at 25th Army headquarters met a British party seeking to discuss terms of surrender.

The Japanese staff officer told the British officers, “We will have a truce if the British Army agrees to surrender. Do you wish to surrender?” The British interpreter agreed. Then, Yamashita ordered that Percival and his staff come to him in person to the Ford Factory at Bukit Timah after reviewing the Japanese truce documents.

At 6:00 pm, Percival, accompanied by two staff officers and an interpreter, met with Yamashita. The 25th Army commander wanted the negotiations to be brief. When Yamashita asked Percival if he agreed to an unconditional surrender to be immediately implemented, the British general responded that he wanted to wait until the next morning to answer.

The discussions grew tense. Yamashita knew of the numerically superior Allied troop strength, and he did not want any delay in an unconditional surrender since this might enable the British to discern the true Japanese troop numbers and their combat deficiencies. Yamashita feared that Percival might become emboldened to continue the struggle despite his major concerns about water, supplies, and the civilian population.

Ironically, on the morning of February 15, Percival had been considering a counterattack to reclaim the food depots at Bukit Timah. Also, the Imperial envoy was to arrive on the battlefield from Tokyo that same day. Yamashita did not relent with his demands for an immediate unconditional surrender and told Percival after his request for an overnight delay, “Then, in that case, up till tomorrow morning we will continue the attack. Is that all right, or do you consent immediately to unconditional surrender.”

Percival agreed after receiving the threat of continued Japanese attack.

After the war, Yamashita said, “I felt if we had to fight in the city we would be beaten.” He went on to reveal that his strategy at Singapore was “a bluff, a bluff that worked.”

Although he had overextended his own supply lines, Yamashita’s skilled strategic planning, tactical audacity, military deception, and the art of bluff on and off the battlefield had produced, within one week of landing on Singapore, one of the largest military disasters in the history of British arms and one of the greatest Japanese land victories ever.

Jon Diamond recently visited the Memories at Old Ford Factory Museum on Upper Bukit Timah Road on Singapore. He has written several articles for Sovereign Media’s WWII History.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments