By Mark Simmons

On Saturday, December 6, 1941, a Royal Australian Air Force Lockheed Hudson bomber on a reconnaissance mission from Khota Bahru on the west coast of Malaya was flying northwest over the China Sea toward the Gulf of Thailand.

At 12:12 pm, near the limit of its range, the Hudson’s crew spotted a Japanese cruiser and three transports steaming in the same direction. Half an hour later a bigger convoy of 18 transports with cruisers and destroyers was spotted south of the first sighting.

Flight Lieutenant John C. Ramshaw took his aircraft down for a closer look. The Japanese did not open fire. The Hudson signaled the sighting back to Khota Bahru.

The reports of the sightings, and that of a second Hudson confirming those of the first, could not have come at a better time for the Commander in Chief Far East, Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham. He had been appointed to the command in 1940. His charge was to avoid war with Japan, if possible.

The Japanese plan to capture Malaya and Singapore was based on Japan’s wish to prevent any risk to shipments of vital oil supplies from the Netherlands East Indies when, as expected, those islands were seized.

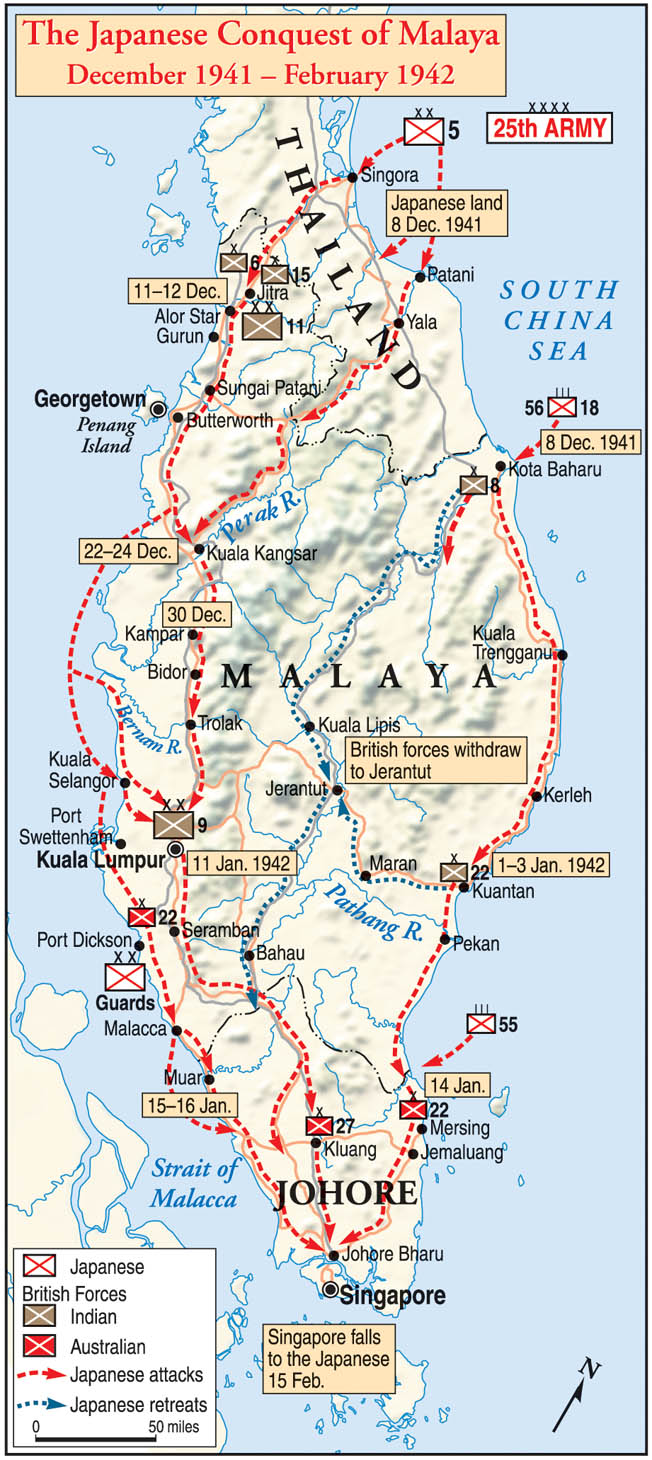

The Japanese also wanted to dent British prestige by capturing Singapore—the naval and commercial symbol of Britain’s empire in the Far East. The 25th Imperial Japanese Army, under General Tomoyuki Yamashita, was given five months to take Singapore and Malaya. He had three divisions under his command: the 5th (Lt. Gen. Takuro Matsui), the 18th (Lt. Gen. Renya Mutaguchi), and the Imperial Guards (Lt. Gen. Takuma Nishimura), for a total of 62,000 men, with 183 guns and 228 tanks.

The 3rd Air Division was attached to 25th Army with 168 fighter aircraft, 180 bombers, and 45 reconnaissance aircraft. The Southern Expeditionary Fleet, with the 22nd Air Flotilla and 158 aircraft, was to protect the convoys.

The plan belonged to the Imperial Navy under Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, but the Army and Navy had bitterly argued strategy, with the Army feeling no move south should be made until China had been conquered.

The Navy wanted the Dutch oilfields and the approval of the emperor for its plan. The first task was to capture Bangkok, the capital of Thailand, to secure Japanese lines of communication to Burma and Malaya.

British strategy in the region was based on political considerations rather than sound military thinking. The Army was in Malaya to protect the air bases. The Air Force was there to protect the naval base on Singapore Island. In times of danger, so the theory went, the Royal Navy would provide the power to deter any invasion; they could be there in force in 48 days.

Additionally, the British had not even considered the possibility of a land attack from the thick jungles to the north; their 15-inch coastal defense guns at Singapore pointed out to sea; they could not be rotated to fire at a threat from the north. In 1940, First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill had gone so far as to smugly declare that any attempt by Japan to capture Singapore would be “a mad enterprise.”

Certainly, by the middle of 1940 British intelligence was well aware of Japan’s military planning through its signals intelligence (Sigint) based on intercepts of Japanese telegraphic messages. Commander Eric Nave from the Royal Australian Navy’s cryptographic unit, and Hugh Foss, a Scot, were the two men principally responsible for breaking Japanese naval codes in the prewar years.

Japanese intelligence was also aware of the poor state of Singapore’s defenses through spies on the ground. In 1940, the Japanese had received documents captured by the Germans from the British cargo ship Automedon, which contained secret British reports and was captured and sunk by the German surface raider Atlantis. One of the captured reports included the minutes of the British War Cabinet meeting of August 15, 1940. It outlined the Far East policy, including the defense of Malaya, and revealed Hong Kong and Borneo to be indefensible while Singapore could not be reinforced. Nor would Britain go to war if Japan attacked Thailand.

However, by 1941, the Royal Navy was heavily engaged in the Atlantic and Mediterranean and had few resources to spare in the event of Japanese aggression in or near Malaya. In 1941, the Admiralty did, however, work on a plan to create Britain’s third fleet—the “Eastern Fleet.” It was to consist of seven battleships, one aircraft carrier, and numerous cruisers and destroyers. However, the capital ships selected were old or slow, including the old battlecruisers Renown and Repulse and the battleships Nelson and Rodney, along with other well-worn ships.

Time was against the Royal Navy; many of the ships needed refitting and the latest radar equipment installed. The biggest drawback was that destroyers were not available, being fully committed in the Home and Mediterranean Fleets or for convoy work. Implementation of the plan was postponed to an optimistic March 1942.

After becoming prime minister, Winston Churchill had made his view clear to the First Sea Lord that a strong force should be sent to the Indian Ocean. “The most economical disposition would be to send Duke of York as soon as she is clear of constructional defects, via Trinidad and Simonstown to the East. She could be joined by Repulse or Renown and one aircraft carrier of high speed. This powerful force might show itself in the triangle Aden-Singapore-Simonstown. It would exert a paralysing effect upon Japanese Naval action.”

It was the new battleship Prince of Wales (commissioned January 1941) that finally sailed for Cape Town. Later she joined the aging battlecruiser Repulse at Ceylon; both ships arrived at Singapore on November 11, 1941. It was planned that the new aircraft carrier HMS Indomitable, working in the West Indies, would join the small fleet.

However, on November 3, Indomitable ran aground on a reef off Bermuda and damaged her hull; she was ordered to Norfolk, Virginia, for repairs. The U.S. Navy dockyard worked fast, and she was away in 12 days. But it was all too late by the time she reached the Indian Ocean; the fate of Prince of Wales and Repulse, designated Force Z, was settled. The two warships were sunk by Japanese aircraft on December 10.

The Royal Air Force had 158 aircraft, some of which were obsolete, to defend Singapore and Malaya. It had been estimated that some 550 first-line aircraft were needed for an adequate defense. The Army had III Corps consisting of the 11th and 9th Indian Divisions and the 8th Australian Division with the Singapore Fortress troops and a reserve brigade, for a total of 88,600 men.

The British had planned a preemptive strike, Operation Matador, to meet the Japanese head-on in southern Thailand. It was a good concept. A 24-hour warning of a Japanese landing was all it required for to be effective. Brooke-Popham had the warning, and he was also free now from asking permission from the War Cabinet to order Matador.

On December 1, Britain obtained a pledge of American support in the event of war with Japan. However, it was conditional on a Japanese attack on British territory. “They’ve made you personally responsible for declaring war on Japan,” observed Brooke-Popham’s chief of staff, General Ian S.O. Playfair.

Matador’s plans included the occupation of Singora and Patani in Thailand. However, due to troop shortages, this was not possible. The operation was revised with the main force, the 11th Indian Division based in Kedah, moving as far as Singora, 130 miles north of the Malayan border.

A smaller force from the Penang garrison would drive along the Patani Road from the border town of Krah. Its objective was the Ledge, 35 miles on the Thai side of the frontier. The road here was cut into the sheer side of a hill and could easily be blocked. The plan envisioned the Japanese being resisted at Singora, allowed to land at Patani, and then boxed in at Krah.

There were several beaches in eastern Malaya that the Japanese could use for amphibious landings. The four most likely were Khota Bahru, defended by 8th Indian Brigade, Kuantan, Endau, and Mersing much farther south and defended by the Australians.

At that time of the year, the northeast monsoon could whip up the seas, but even in these conditions landings were possible; only the most severe weather would stop the Japanese. Fixed defenses had been built at Jitra, inland near the Thai border, to defend the airfields but not the border itself. Even those were incomplete.

On December 6, General Arthur Percival, commander of Commonwealth forces in Malaya, flew north to clear up some matters regarding Operation Matador with General Sir Lewis Heath, commander of III Indian Corps, who was not in favor of the operation. That evening Percival returned to Singapore to find that Brooke-Popham had not activated Matador. Even with everything pointing to a Japanese invasion, the commander in chief could not make up his mind.

On the afternoon of December 6, a Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boat failed to locate the enemy fleet. Another Catalina found the Japanese convoy 80 miles south of Cape Cambodia sailing west toward Thailand. The Catalina was shot down by the convoy’s air cover before it could report the sighting, and Hudson bombers failed to find the convoy due to poor visibility. Thirty crucial hours had passed since the first sightings; Matador waited.

At 5:50 pm, another Hudson spotted the convoy and was shot at but sent a radio signal. The convoy was 70 miles north of Singora, steaming south toward Patani and Khota Bahru.

Brooke-Popham still dithered. He met Percival at 9 pm on the 6th in the War Room at the naval base on Singapore Island. At 10:30 pm, Admiral Sir Tom Phillips, commander of Force Z, joined them. At last a decision was made. Matador would be activated at dawn on December 8. That would, however, be too late.

Shortly after midnight on Sunday, December 7, Mutaguchi’s 18th Division began landing at Khota Bahru (where the 3/17 Dogra Regiment was defending the beaches); the 3rd Air Division began bombing and strafing the airfield a mile and a half inland. A few hours later the Japanese had 26,000 men ashore. Meanwhile, the 5th Division landed in Thailand at Singora and Patani.

At dawn on December 7, the Indian troops at Posts 13 and 14 of the 3/17 Dogra Regiment reported they were about to be overrun as Japanese landing craft continued to disgorge their troops. British 18-pounder guns opened fire, and Japanese warships replied. Many in the first wave of assaulting troops were cut down by machine-gun fire. Some of the landing craft came into the creek between the Bandang and Sabak beaches and attacked the defenders from the rear. By 1 pm, after savage hand-to-hand fighting, the beaches were cleared by the Japanese troops.

The Australian Hudsons from Khota Bahru airfield attacked the Japanese transports off the beaches with some success. One burst into flames after being bombed and was abandoned; another was damaged. Japanese soldiers leaped over the sides of the stricken ships or scrambled into landing craft as Hudsons bombed and strafed them. Two Hudsons were shot down by antiaircraft fire.

General Heath could hardly believe his situation. His III Indian Corps would have to stand-to all night awaiting the order to move into Thailand. Shortly after midnight on December 8, he telephoned Singapore, rousing Percival from his bed with the news the Japanese were ashore at Khota Bahru.

Admiral Phillips had not returned from Manila, where he had held talks with American Admiral Thomas C. Hart about joint action with the U.S. Asiatic Fleet. At the War Room meeting he suggested he could take his ships to sea and head north, reasoning that if an invasion was under way he might be able to stop it before the Japanese gained a foothold.

He put his plan to those at the meeting and asked for land-based fighter cover. Air Vice Marshal Conway Pulford indicated the limitations of his fighter pilots and lack of training in the naval support role, although they would try to support Force Z. The meeting was broken up by an air raid warning. At 4:30 am, Japanese bombers hit Singapore.

Phillips signaled the Admiralty at 6 am on December 8 and told them he was taking Force Z to sea toward Khota Bahru: “I rate the chances of getting there no higher than 50-50, but I’m sure it’s the only way in which to halt the invasion and, if it can be halted, they should find it impossible to start again. Surprise is absolutely essential but it is just possible in this thick monsoon weather, given even an average amount of luck. But, if we are spotted, which is bound to happen sooner or later, we shall be attacked.”

At last Percival informed General Heath at his Kuala Lumpur headquarters that the Japanese were already in Singora and Patani and told him to send a mobile force across the border to delay the enemy advance. Then, at 10 am a message arrived at Heath’s headquarters, canceling Matador. After the war, Heath wrote, “I find it impossible to excuse General Percival for permitting Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham not to arrive at a decision on 7 December when everything pointed to the certainty of Japan initiating the war in Malaya.”

It was a terrible mix-up that only benefitted the Japanese. Seventy minutes before the aircraft of the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor, troops of General Yamashita’s 25th Army were pouring ashore on the beaches at Khota Bahru.

All through December 8, about 150 aircraft of the 7th Japanese Air Brigade flying initially from southern Indochina attacked the seven RAF airfields in northern Malaya. Pulford had started the day with 110 aircraft at these bases. By the end he had half that number—40 had been destroyed and 20 damaged—forcing him to withdraw the remaining aircraft south. The Japanese had won air superiority in a single day.

Singora and Patani soon fell to the Japanese 5th Division, which brushed aside token resistance from the Thai Army. The Japanese soon had 60 aircraft operating from Singora airfield and over 100 farther north at Bangkok.

Brigadier Berthold Key, commander of 8th Brigade of the Indian 9th Division, ordered two of his battalions to counterattack the Japanese on the beaches at Khota Bahru. However, the assault quickly broke down in a heavy monsoon downpour, and Key’s men failed to stop Japanese attempts to take the airfield. Although Pulford had ordered the aircraft sent farther south to Kuantan, about midnight the airfield fell after desperate resistance by the Indian troops.

At 7 pm, Japanese ships were back at the beaches landing more troops. Key had no option but to withdraw to Khota Bahru town. In the deluge, his troops struggled to retreat with many getting lost, while others did not receive the order and remained in their trenches to be wiped out.

Brooke-Popham’s hesitation had already severely weakened the 9th and 11th Indian Divisions and the RAF. Pulford’s air force was now largely tasked with the defense of the naval base at Singapore and the protection of convoys bringing supplies and reinforcements.

This highlighted the flawed strategy the British had adopted. The Army had been deployed to protect the airfields, and half of Percival’s infantry battalions in northern Malaya were committed to this role. Instead, they should have been dug in along the main routes south with strong mobile forces in support. With well-trained troops and adequate transport, it might have been possible to transfer troops as needed, but this would prove extremely difficult.

At 5:10 pm on December 8, the Australian destroyer Vampire led Force Z away from Singapore. She was followed by the destroyer Tenedos, then Repulse and Prince of Wales and two more destroyers, Electra and Express. It was a fine evening and, as the ships moved down the Johore Strait, spectators lined the shore to wave them off. The onlookers must have been heartened at the sight.

Some on board the ships were not so confident. Seaman W.S. Searle of Prince of Wales wrote, “We had left Singapore in glorious weather but I had this premonition that the Prince of Wales would never return to Singapore or any other port. I had this feeling that this was the end as far as the ship was concerned.” He was right.

Admiral Phillips was as concerned as Seaman Searle as messages came in from Rear Admiral Arthur Palliser in Singapore. The RAF would provide reconnaissance from 8 am on December 9, but only with one Catalina up to a range of 100 miles northwestward. Even worse, “Fighter protection on Wednesday 10th will not, repeat, not be possible.” And, “Japanese have large bomber forces based southern Indo-China and possibly in Thailand,” and that the military situation at Khota Bahru “does not seem good.”

However, the RAF had not abandoned the Navy altogether, although heavily engaged in the land fighting in northern Malaya. Number 453 Australian Squadron with Brewster Buffalo fighters at Sembawong airfield on Singapore Island were tasked to support Force Z.

At 1:30 pm on December 9, Force Z was spotted by the Japanese submarine I-65. The submarine managed to stay in visual touch until 3:50, when the ships entered a squall and contact was lost. The submarine regained contact about 6 pm but an approaching aircraft forced it to dive. When I-65 surfaced there was no sign of the ships. There had been a two-hour delay from the first sighting and the receiving of the signals from I-65.

The Japanese Navy was convinced the British ships were still in Singapore, so it came as a shock to find them heading toward Khota Bahru. Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa aboard the cruiser Chokai was about 120 miles from the reported position of the British ships and ordered all Japanese warships in the area to search for the British in the remaining hours of daylight. Several of Ozawa’s cruisers launched their seaplanes to aid the search.

About an hour before dusk, Prince of Wales’ radar picked up three aircraft—seaplanes from the Japanese cruisers. They kept out of antiaircraft range and plotted the course and speed of Force Z, relaying this information to Admiral Ozawa.

By 8:15, Admiral Phillips knew Force Z had been sighted. At 8:55, Prince of Wales signaled Repulse: “Have most regretfully cancelled the operation because, having been located by aircraft, surprise was lost and our target would be almost certain to be gone by the morning and the enemy fully prepared for us.”

Force Z was returning to Singapore. However, just before midnight, Admiral Palliser signalled: “Enemy reported landing Kuantan. Latitude 0.350 north.”

Phillips was well aware that if the Japanese seized the road running inland from Kuantan, Malaya would be cut in two. He turned his ships toward Kuanton and increased speed to 25 knots. He was keen to catch the enemy by surprise, so he did not break radio silence to inform Singapore of his change of plan, feeling this might reveal his position to the enemy.

Phillips seems to have assumed Palliser would arrange air cover for the morning of the 10th; No. 453 Squadron was on standby to support Force Z. However, nothing was done, the Kuanton report was a false alarm, and RAF HQ at Singapore had no idea where Force Z was.

The Japanese submarine I-58 spotted the British ships about midnight on a southerly course and shadowed on the surface, sending several signals after first trying an unsuccessful torpedo attack.

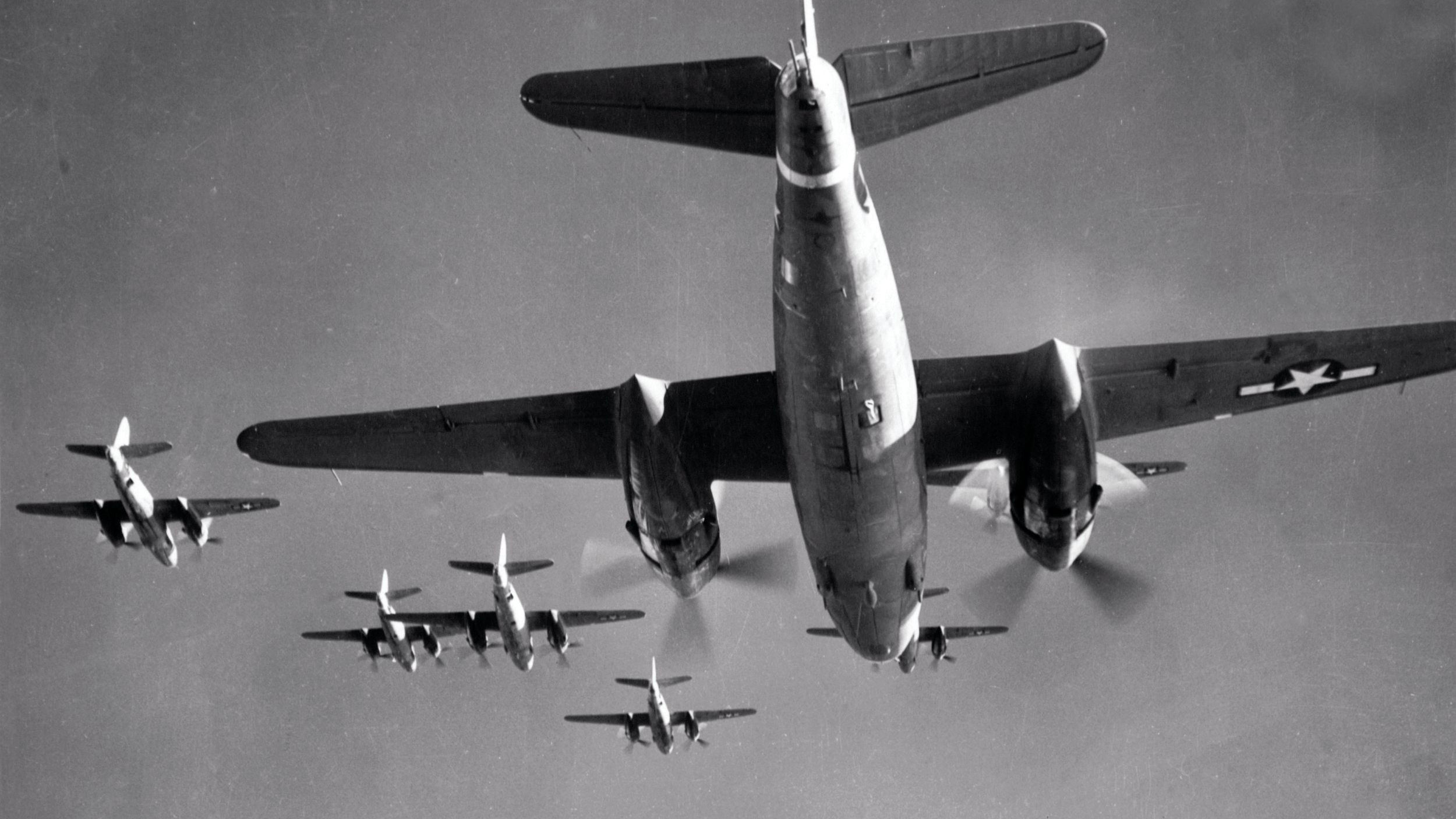

The position of Force Z was relayed to the Japanese 22nd Air Flotilla in French Indochina; on December 9 it had tried to find the British ships without success. At 6 am on the 10th the Japanese launched 30 bombers and 50 torpedo bombers. They flew south 150 miles beyond Kuanton, almost as far as Singapore, but spotted nothing. However, on the return a break in the clouds revealed the British ships. The high-level bombers came in first at about 11 am, followed by the torpedo bombers.

The British ships had spotted the Japanese aircraft on radar. In the very first attack, Repulse and Prince of Wales were hit by bombs, and then a torpedo hit the flagship.

Captain Bill Tennant of Repulse reported after the action, “The second attack was shared by Prince of Wales and was made by torpedo-bomber aircraft. I am not prepared to say how many machines took part in this attack but, on conclusion, I have the impression that we had succeeded in combing the tracks of a large number of torpedoes, possibly as many as twelve.

“We were steaming at 25 knots at the time. I maintained a steady course until the aircraft appeared committed to the attack, when the wheel was put over and the attacks providentially combed. I would like to record the valuable work done by all bridge personnel at this time in calmly pointing out approaching torpedo-bombing aircraft which largely contributed to our good fortune in dodging all these torpedoes.”

Repulse tried to help Prince of Wales, but Repulse was hit again by a bomb, then four more torpedoes hit Prince of Wales. Having dodged 19 torpedoes, Repulse was struck five times; she rolled over at 12:33.

Sergeant H.A. Nunn of the Royal Marines aboard Repulse recalled, “It was time for me to go over the side, so I kicked off my shoes and climbed over the guardrail. It was possible to walk partway down the ship’s side, but I had to finish the rest of the journey on my seat, regardless of the rips and tears to my person and clothing. I had my lifebelt with me but I had no qualms about going into the water, as I was a strong swimmer.

“I didn’t even think of the possibility that there may be sharks in the vicinity. My only concern was to try and get away from the ship and the oily patch that was beginning to spread out over the surface of the water.”

From Repulse, 796 men out of a complement of 1,309, including Captain Tennant and Sergeant Nunn, were rescued. The destroyer Express came in to take men off the stricken Prince of Wales.

Lieutenant W.M. Graham remembers surviving as Prince of Wales keeled over. “I was able to muster most of my close-range gun crews over on the starboard side and remember quite clearly walking over the bilge keel, keeping pace with the roll, and thinking how clean the ship’s bottom looked as I swam away. The last time I had seen the underside of the Prince of Wales was when I saw her being launched at Cammell Laird’s yard at Birkenhead [Liverpool] in 1939.”

The Buffaloes of No. 453 Squadron arrived just in time to see Prince of Wales go down. Flight Lieutenant Tom Vigors recalled seeing the survivors in the oily water waving to him. “I [saw] many men in dire danger waving, cheering, and joking as if they were holidaymakers at Brighton waving at a low-flying aircraft. It shook me, for here was something above human nature. I take off my hat to them, for in them I saw the spirit that wins wars.”

Winston Churchill stated, “In my whole experience, I do not remember any naval blow so heavy or so painful as the sinking of Prince of Wales and Repulse.”

The loss of the British warships was a huge boost to Japanese prestige, bolstering the myth of their invincibility. In Berlin, Adolf Hitler was jubilant at the news and then made the fatal mistake of declaring war on the United States.

In Malaya, the British Army was now largely on its own. On December 8, General Matsui’s 5th Division had started moving south from Singora and Patani, hoping to cross the Perak River. The British Operation Krohcol was designed to foil this move. However, the British needed to win the race to the Ledge—the road cut into the hillside above the Patani River.

Major General David Murray-Lyon’s force, assigned this role, got off to a bad start and did not arrive at the start line on December 8. However, the 3/16 Punjabis were there and started forward into Thailand on their own without artillery support. They soon ran into trouble with the Thais, who had been told to defend the country against the British in the hope of not provoking the Japanese. Thus, the Thai police were manning roadblocks, unaware the Japanese had invaded, and delayed the British advance.

The next day the Punjabis got within six miles of the Ledge but soon came under fire from the Japanese 42nd Regiment, supported by tanks, which had beaten them there. The 3/16 was forced to withdraw and suffered heavy casualties.

Another British force, this time mechanized and with artillery, advanced into Thailand from Kedah along the Singora-Jitra Road and ran into a Japanese column. The British gunners brought the column to a halt, but Japanese infantry swarmed into the jungle and soon outflanked the position, forcing back the British, who then destroyed bridges as they rejoined the 11th Indian Division at Jitra.

The Jitra line was not strong or based on natural features, and Murray-Lyon spread his forces too thinly over a 12-mile front from Jitra to the sea instead of concentrating on the two main roads leading into Jitra from the north.

The Japanese had captured a map showing the British defenses at Jitra. Their attack was reckless but the tanks carried them through the poorly prepared lines. In 15 hours, the Japanese broke through and 3,000 Indian troops surrendered. Huge amounts of equipment were captured—enough ammunition and food to keep the Japanese going for months. The Japanese poured into northern Malaya along good roads, the infantry speeding along on bicycles. On the east coast, the 18th Division took Khota Bahru.

Murray-Lyon’s request to withdraw 30 miles south to Gurum was refused. However, he repeated the request as the Japanese advance from Kroh threatened to cut him off. On December 13, his tired, rain-soaked, and largely confused men trudged south. At Gurum, the 6th Brigade headquarters was destroyed and the 11th Indian Division was in danger of collapse. They withdrew beyond the Muda River, losing men constantly. By December 20, they were farther south, near Taipang, leaving Penang uncovered. The British lacked air cover. The outdated Buffaloes were no match for the Japanese Zero fighters.

From Brigadier Archie Paris’s reserve 12th Brigade, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders were pushed forward to Bailing on the main road from Kroh with three companies, while C Company with armored cars went to Grik in case the Japanese used that mountain track. The Argylls were one of the few British infantry units that, thanks to their commanding officer, Lt. Col. Ian Stewart, had undergone rigorous jungle training. Many desk-bound soldiers thought Stewart, who kept his soldiers “square-bashing,” was “barking mad.”

Stewart created fast-moving Tiger Patrols designed to encircle enemy troops and drive them into roadblocks of artillery, mortars, and armored cars. Now he was about to put his tactics to the test.

In the first clash, the Japanese lost heavily. However, weight of numbers forced the Argylls back. Company C managed to hold back the 42nd Japanese Infantry Regiment for a time but had to fall back to Sumpitan, conducting a fighting withdrawal down 150 miles of the Grik Road.

With the 5/2 Punjabis, the Argylls fought at Sumpitan, Lenggong, and Kota Tampan. Captain Kenneth McLeod paid tribute to the support provided by the 2/3 Australian Motor Transport Company. “They were always at the waiting points ready to take our troops. Every now and again, they would grab a rifle and have a shot at the enemy. They were great chaps.”

Lieutenant General Sir Henry Pownall reached Singapore on December 23 to take over command from Brooke-Popham and wasted no time in touring the battlefields on the western front. He hoped to hold the Japanese at Kampar, a hill position that gave scope for artillery, an arm in which the British were superior. He wrote, “The 11th Division have had a pretty good shaking up. They were thrown on to the wrong leg and took some time, indeed too long, to recover. Heath is, I think, all right. He has aged a lot since I knew him in India. He’s not ‘full of fire,’ but he does know what is to be done to pull the troops around.”

Pownall was not overly impressed by Percival and confided to his diary that he hoped he wouldn’t have to relieve Percival, whom he found lacking in inspiration and “gloomy.”

The combined remnants of the 6th and 15th Brigades were to dig in at Kampar, while the 12th and 28th Brigades fought delaying actions to the north. Eleventh Division commander Murray-Lyon and all three of his brigade commanders had been replaced. On the night of December 27-28, Archibald Paris, Murray-Lyon’s temporary replacement, sent his own 12th Brigade south of Ipoh.

The 28th Brigade was to join the defenders at Kampar while the 12th Brigade delayed the Japanese approach, then withdraw through Kampar to Bidor. They were largely ineffective at delaying the Japanese; the Argyll’s armored cars came to their aid by holding the bridge over the Kampar River and allowing them to pass. By the time 12th Brigade reached the reserve position, it was shattered, losing 500 men and most of its vehicles.

The British commanders were well aware that reinforcements—the 18th British Division and 50 Hurricane fighters and pilots—were on their way. It was vital to hold the Japanese as far north as possible to keep their aircraft away from Singapore; but the convoy was not expected to arrive until January 13-15.

On December 31, the Japanese started probing the positions at Kampar. The next day, the main attack came, with bitter fighting lasting 48 hours. Then the 6th and 15th Brigades started to pull back. However, it was not the assault at Kampar that forced this withdrawal; the Japanese had outflanked the position by sea. In an armada of small boats they had used the Perak River via Telok Anson.

When news of the landing reached Brigadier Paris, he sent the weakened 12th Brigade from Bidor to stall the enemy. The Argylls and 19th Hyderabad Regiment initially held the Japanese 4th Guards at Telok Anson. The fighting was fierce, and the Argylls bore the brunt of the attack. The 12th Brigade could not keep the road south open, so the good position at Kampar was lost and the 11th Division withdrew to an inferior one on the Slim River.

The 12th Brigade took up positions on a stretch of road between Songkau and Trolak, with the 28th Brigade covering the line eastward along the road to the Slim River Bridge. Most battalions were down to company strength and lacked antitank defenses, and the country did not favor field artillery.

On January 5, the Japanese attacked down the railway line after 12th Brigade had been heavily bombed. They were initially thrown back but came forward the next day via the railway and road with tank support. The bridge over the Slim River should have been blown but was taken intact.

The thrust came to a halt with the Japanese penetrating 19 miles into the 11th Division’s area. With the loss of this battle, central Malaya was gone and with it the largest city, Kuala Lumpur.

Australian Maj. Gen. Henry Gordon-Bennett became more involved in the battle after the decision was made to make an extensive withdrawal into Johore. Giving up the provinces of Negri Sembilon, Selanger, and Malacca, this would mean fighting in open country where Japanese armor would be even more useful. However, Gordon-Bennett felt he had a good chance to hold the Japanese, although he had not been impressed by the display of British leadership so far. The decision was taken to stand at Muar, where there were no bridges over the Muar River’s lower reaches.

On December 30, General Archibald Wavell was appointed Supreme Commander, South West Pacific. On January 7 he arrived in Singapore then flew north to review the situation. He soon confirmed Percival’s opinion that the decisive battle should be fought in northwest Johore using the Australians and 45th Indian Brigade. It was hoped this would give time for the 18th British Division to arrive and for the 9th and 11th Divisions to rest and reorganize.

Wavell was impressed with Gordon-Bennett even if the Australian was dismissive of the Indian soldier’s lack of fighting qualities. His contention that “one Australian is worth 10 Japanese” was largely bluster. However, Wavell was well aware of the fighting spirit of Australian troops and he felt Gordon-Bennett was the aggressive commander needed. He informed London that Gordon-Bennett would “conduct very active defence and will hopefully be able to delay enemy till collection of reserves enables us to deliver counter-stroke which will not be before the middle of February.”

On January 13, the 53rd Brigade of 18th British Division disembarked in Singapore with 50 Hurricane fighters but only 25 pilots.

Meanwhile, Yamashita was resting his 5th Division at Seremban, 30 miles south of Kuala Lumpur, while the Imperial Guards concentrated in Malacca. By this time the remainder of Mutaguchi’s 18th Division had landed at Singora. On January 14, the Japanese moved against the Australians of Gordon-Bennett’s Westforce.

At Gemas, the Japanese were allowed to cross the river via a bridge, but it was then blown behind them. They met the 2/30 Australian Battalion and a field artillery battery, which cut the Japanese to pieces. The renewed attack the next day was repulsed, but pressure increased and the Australians withdrew that night.

On the west coast, the Japanese landed by sea behind the British position at Muar, then cut the Muar-Bakri Road behind the British 45th Brigade. The road to Yong Peng was open, threatening the Australians in the center. Gordon-Bennett sent the 2/29 Battalion to reinforce Muar.

While the newly arrived 53rd Brigade (which had been on ships for three months) relieved an Australian battalion on the east coast, Percival was convinced he now faced five Japanese divisions and flung the 53rd into the fight before it was acclimated.

More Japanese landings were made between Muar and Batu Pahat. The British 45th Brigade was ordered to recapture Muar to allow the Australians in the center to withdraw south from Segamat before becoming trapped. The counterattack soon broke down, the brigade having to fight its way back through Japanese roadblocks.

Finally, the 45th, with the 2/29 Australians, took to the jungle, abandoning vehicles and guns. Out of 4,000 men, fewer than 1,000 made it back; the Japanese massacred the wounded. However, their sacrifice had held up the Imperial Guards, allowing Westforce to escape south.

The next defense line was 90 miles south, crossing Malaya from Batu Pahat through Kluang to Mersing on the east coast. This was III Corps’ area, and Lt. Gen. Heath took command. Percival ordered no retreat without his permission. However, it was the same story as the Japanese moved by sea. At Batu Pahat, the 6/15 Brigade was withdrawn after losing half its strength, 2,700 men escaping the surrounding Japanese by sea. This compelled Westforce at Kluang to pull back.

Thanks to two Australian battalions, in six days of fighting ending on January 22, Muar Force managed to destroy a company of Japanese tanks and the equivalent of a battalion of Imperial Guards.

General Yamashita was now running behind schedule. He wrote in his diary that Nishimura, commander of the Guards Division and Matsui of the 15th Division, had disobeyed his orders and delayed the advance.

In the east, the Australians repeated their ambush technique near Hersung, luring the Japanese into a “firebox” of rifle companies and field guns and wiping out a Japanese force. But such actions did not reverse the trend of withdrawal.

On January 30, Wavell authorized Percival to withdraw to Singapore Island. The Japanese managed to slip between the retreating brigades of the 9th Indian Division and, during this last period of the mainland campaign, the 45th and 22nd Indian Brigades suffered so many causalities they no longer existed. The III Corps arrived at Singapore Island with several thousand men missing.

On January 22, the 44th Indian Brigade arrived with 7,000 raw, untrained men. Two days later, 1,900 Australians arrived in a similar state, but with them was the 2/4 Australian Machine Gun Battalion—a welcome reinforcement. A week later the bulk of the 18th British Division arrived; the 54th and 55th Brigades came ashore from American transport ships.

Unfortunately, the Empress of Asia, carrying 2,235 members of 18th British Division, including the Reconnaissance Battalion, 9th Northumberland Fusiliers, 125th Anti-Tank Regiment, and other elements, was bombed and sunk on February 5, almost within sight of Singapore. Much of the crew and almost all the soldiers were rescued, but all the equipment was lost.

The Australians crossed the Causeway at dawn on January 31, but it was the Argylls that were the last unit to cross—with their pipers playing “Hielan Laddie.”

Major John Wyett asked Lt. Col. Ian Stewart why he did that. “You know, Wyett,” Stewart said, “the trouble with you Australians is that you have no sense of history. When the story of the Argylls is written, you will find they go down in history as the last unit to cross the Causeway—piped across by their pipers.”

The population of Singapore had swollen to nearly a million. To defend it, Percival had 85,000 men—17 Indian battalions, 13 British, six Australian, and two Malay. But numbers are misleading; many units had been battered in the mainland campaign while others were raw from the convoys. Some of those had never even fired a rifle before.

Percival divided the island into four sectors: the City held by the Malaya Brigade and Fortress troops; the Northern area, including the naval base, held by III Corps, reinforced by 18th Division; and the Western area held by the 8th Australian Division; the 12th Indian Brigade formed the reserve and held the water reservoirs.

Percival had parceled out his men to cover all possible shore landings, a recipe for failure. He believed the Japanese would attack east of the Causeway. His main concern was holding the naval base, but that was near useless now. Wavell had told Percival that, in his opinion, the Japanese would attack in the northwest along the route of their main axis of advance down the west coast of Malaya. To move their entire force from west to east to cross at a wider spot made no sense to anyone except Percival.

Although the situation looked grim, many of the British refused to concede. On January 29, 1942, 210 Royal Marine survivors from Prince of Wales and Repulse, under Royal Marine Captain Bob Lang, joined 250 men of Major Angus Rose’s 2nd Argylls to carry out operations using boats to strike from the sea 140 miles behind Japanese lines. As both detachments were from the Marine Plymouth Division, the composite unit, officially called the Marine Argyll Battalion, became known as the Plymouth Argylls after the English soccer club of that name. Roseforce, as they were also known, set ambushes, destroyed vehicles, and killed two senior Japanese staff officers in their cars.

On February 6, Yamashita issued his attack orders to his senior commanders. The assault on Singapore would begin at 8:30 pm, February 8. The 5th and 18th Divisions would land on the west coast, their first objective Tengah airfield. In the second phase, the Imperial Guards would attack the Causeway sector and then isolate British forces in the naval base. Next would be the water reservoirs. When these were taken, Yamashita calculated the British would surrender.

Nishimura was not happy that his Guards were relegated to the second phase, which he viewed as an insult. Yamashita’s chief of staff, General Sosaku Suzuki, tried to smooth things over between the two men but failed.

Churchill expected a battle in the streets and told Wavell, “I expect every inch of ground to be defended … and no question of surrender to be entertained until after protracted fighting among the ruins of Singapore City.”

On the night of February 8, Japanese artillery opened fire with 440 guns using 200 rounds per gun all along the Johore Strait. At 8:45 pm, the first wave of 4,000 Japanese troops crossed the Johore Strait and gained a foothold on Singapore’s northwestern shore. Meanwhile, the Imperial Guards had been demonstrating in east Jahore, feigning an attack from the northeast. Over the next hour, the whole front from the Buloh River to the righthand company of the 2/19 Battalion was under attack. The Vickers machine guns cut up the invaders, but still they came on, closing in on the 2/19’s weapon pits. The men there held out for only 15 minutes before being overrun.

As the exhausted Australian defenders withdrew, the Plymouth Argylls were ordered on the morning of February 9 to advance northward up the Bukit Timah Road then westward along the Choa Chu Kang Road toward Tengah airfield.

Shortly after arriving, the Royal Marines came under air attack, and some sections became lost in the unfamiliar terrain. Two more days of fighting followed as the Plymouth Argylls engaged the Japanese between Tengah and the dairy farm that lay east of the Upper Bukit Timah Road. Most of the Argylls were cut off when the Japanese brought their tanks down the road and smashed through two roadblocks.

The main body of Royal Marines escaped across the dairy farm and down the “Pipeline” to the golf course. No sooner had they arrived at Tyersall Park than the camp and the neighboring Indian military hospital were destroyed in an air attack. In the confusion that followed and subsequent shelling and mortaring, there was a further dispersal of men, including the wounded.

By late morning on the 9th, both Japanese divisions were ashore along with their artillery. The 44th Indian Brigade hung on, but the 22nd Australian Brigade, which bore the brunt of the attack, was wrecked. Although reinforced by the 6th and 15th Brigades, the Australians were split up by the enemy’s infiltration tactics. That night, Yamashita set up his headquarters in a rubber plantation just north of Tengah airfield.

The next morning, Percival still found it hard to believe that no attack would come in the northeast, so he left all the formations there intact but moved the 12th Indian Brigade to the Bukit Panjang area. This brigade now consisted of the 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (aka the Plymouth Argylls) and 400 men of the 4/19 Hyderabads.

On the evening of February 9, the Imperial Guards came across the strait near the Causeway. The Japanese wanted to take Singapore by Kigensetsu Day, February 11, the founding day of the Japanese Empire. By dawn on the 11th, they had taken Bukit Timah.

To hasten the British capitulation, a message was dropped by air urging Percival to surrender; he ignored it.

The defenders at the city’s water reservoirs were attacked on February 12, but by now the 5th and 18th Japanese Divisions were exhausted. The Guards were now the main strength, although Yamashita disliked them and their commander. He had to rely on them, but they refused to be hurried.

Repairs to the Causeway were completed, and Japanese forces to the north were streaming onto the island. The Japanese realized their artillery ammunition was running out, while the British gunners were devastating and seemed to have an inexhaustible supply of shells. One Japanese infantry attack was broken up by a furious barrage before it could start.

From London, Churchill demanded, “There must be no thought of sparing the troops or population; commanders and senior officers should die with their troops. The honour of the British Empire and the British Army is at stake.”

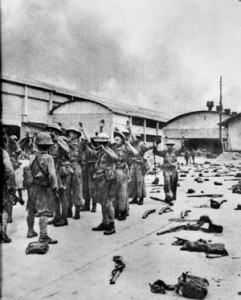

The demand went unheeded. At 2 pm, February 15, surprising news reached Yamashita that a peace envoy—a brigadier with a white flag—had appeared on the front line. At first the Japanese thought it was a trick. Major Kunitake, one of Yamashita’s staff officers, felt the white flag was a ruse, for the Japanese infantry was dropping with fatigue and beginning to wonder if they might be the ones to surrender. Later in the day Percival came himself to the Ford Factory at Bukit Timah to sue for peace.

In his diary Yamashita wrote of his anxiety during that meeting: “I now realized that the British Army had about 100,000 men against my three divisions of 30,000 men. They also had many more bullets and other munitions than I had. I was afraid … that they would discover that our forces were much less than theirs.”

He adopted a hectoring manner with Percival to hide his anxiety. He emphasized “Yes” or “No” in English several times as to whether Percival was going to surrender. Finally Percival agreed and signed the surrender document, and the two generals shook hands. At 8:30 pm on February 15, 1942, the British troops on the island ceased fire.

The Plymouth Argylls were one of the few units that fought with distinction in the dying days of the Malayan campaign, battling to the end, while many other units deserted or tried to force their way onto ships in the harbor. The surviving Plymouth Argylls went into captivity and spent the next 31/2 years in the atrocious conditions of Japanese prison camps working as slave laborers on the infamous Burma-Thailand “Death Railway.”

Percival was undoubtedly influenced in his decision by Japanese atrocities at the Alexandria Hospital on February 14, when the wounded and staff were massacred in cold blood. These were the “Butchers of Nanking,” well known for their brutality. Percival was a humane man, and he had to consider Singapore’s vast civilian population in a prolonged resistance.

Later, while summing up the campaign, Percival felt defeat was due to British inferiority in the air and a lack of tanks. However, Yamashita felt racial disunity between British, Chinese, Malays, Indians, and Australians was an important factor.

It is an interesting question to ask how long the British would have needed to fight to turn the tables; Wavell thought the Japanese could be fought to a standstill. But Yamashita could call on resources from China and Manchuria, whereas British reinforcements were limited.

Perhaps Wavell was right; a more aggressive commander might have succeeded. General Stanley Kirby later wrote that he felt the catastrophe rested with more men than just Percival. “One can sum up by saying that those responsible for the conduct of the land campaign in Malaya committed every conceivable blunder. Wavell, Percival, Heath, and [Gordon-] Bennett had all made serious errors of judgement regarding the enemy and the best ways of dealing with him. From the beginning, Wavell, as he later admitted, had underestimated the Japanese soldier just as he overrated Percival’s chances of beating him.”

Instead, in 70 days at the cost of 3,500 dead the Japanese defeated the British and led nearly 100,000 troops into captivity, smashing forever the British Empire in the East. Thousands of British, Indian, and Australian prisoners died in captivity.

Another fine article

Send me more. P Soskin Yanks@hotmail.com thanks