By Al Hemingway

On the bone-chilling night of March 24, 1944, shadowy figures from nowhere out of the ground. They emerged from a makeshift tunnel that led from the German prison camp Stalag Luft III located approximately 100 miles southeast of Berlin to a wooded area outside the barbed wire. Stalag Luft III, situated near a small town called Sagan, was opened in 1942. The Germans believed its desolate location and soil composition would make it difficult for tunneling and escaping.

The escape route, nicknamed Harry, was more than 100 yards from the camp’s perimeter. Unfortunately, the calculations were wrong and the tunnel fell 20 feet short of the tree line. Despite this, the men decided to push on before a German sentry spotted a “wispy column of steam rising from the ground.” Before the tunnel was uncovered and all prisoners were corralled inside, 76 men had crawled their way outside the wire and made off carrying false passports and papers—all but three would be captured—and 50 of the remaining 73 would mysteriously disappear.

The escape route, nicknamed Harry, was more than 100 yards from the camp’s perimeter. Unfortunately, the calculations were wrong and the tunnel fell 20 feet short of the tree line. Despite this, the men decided to push on before a German sentry spotted a “wispy column of steam rising from the ground.” Before the tunnel was uncovered and all prisoners were corralled inside, 76 men had crawled their way outside the wire and made off carrying false passports and papers—all but three would be captured—and 50 of the remaining 73 would mysteriously disappear.

In his newest book, Human Game: The True Story of the “Great Escape” Murders and the Hunt for the Gestapo Gunmen (Berkley Books, New York, 2012, 352 pp., photographs, notes, index, $26.95, hardcover), award-winning newspaper reporter Simon Read takes the reader on an incredible journey that rivals a Sherlock Holmes story as Royal Air Force investigators unravel the fate of the missing airmen by researching every clue, no matter how small, and bringing to justice the individuals responsible for their disappearance.

Enter Squadron Leader Francis P. McKenna. During the war he had been a member of a bomber crew on an Avro Lancaster at the advanced age of 37, which made him an old man. Prior to the conflict, he had made a name for himself as a detective sergeant of the Blackpool Borough Police and became known as “Sherlock Holmes” because of his professionalism, methodical approach to solving crimes, and dedication. He was the perfect man for the job.

McKenna and his team stepped into a murky world of tracking former Nazi henchmen. The problem was they had little or no concrete information that could lead them to the culprits. They spent countless hours searching files, paperwork, and other documents. Unfortunately, they had barriers to hurdle. Much of the documentation had been destroyed by the Gestapo as the Allies were approaching, especially any information on the orders that were given to the executioners to murder the prisoners. The top Nazis, Hitler, Himmler, Göring, and others, were either dead or imprisoned, and McKenna’s team was bent on snaring those who actually pulled the triggers. Also, the eastern portion of the country was in control of the Russians who provided little, if any, evidence of the whereabouts of the murderers.

Read does an excellent job of weaving the story of the escape, how it was planned and executed by the prisoners in Stalag Luft III. Through bits and pieces of information he has unearthed during his meticulous research he is able to describe the harrowing final minutes of those 50 men who were gunned down by their captors.

It took the Royal Air Force team several years of knocking on doors, speaking to relatives of the perpetrators, and following tips to arrest most of those involved in the murders. Some were seized decades later only to receive reduced sentences for their crimes years after the fanfare surrounding the case had been forgotten by most.

Read has written an edge-of-your-seat thriller that readers will find captivating. It is a fitting tribute to those detectives who relentlessly pursued and brought to justice the criminals whose only defense was the much often used excuse, “I was just following orders.”

Captured: The Forgotten Men of Guam by Roger Mansell, edited by Linda Goetz Holmes, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 288 pp., photographs, notes, index, $33.95, hardcover.

Captured: The Forgotten Men of Guam by Roger Mansell, edited by Linda Goetz Holmes, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 288 pp., photographs, notes, index, $33.95, hardcover.

It seems that certain battles, personalities, or events have always been overlooked in World War II. One such tragedy was the seizure of Guam, the southernmost island in the Marianas chain, by Japanese forces in December 1941 and the horrible treatment of the POWs as well as the Chamorros, the native population indigenous to the island. Most of the military and civilian personnel were transported to Japan and used as slave labor for the Japanese war machine. The book goes into great detail describing the horrid living conditions, the incessant beatings, meager rations, and terrible weather conditions that the prisoners had to endure during their tenure as “guests of the emperor.”

Prior to the Japanese takeover of Guam, some men did manage to scatter to the countryside and elude the Japanese. All but one were caught and executed. The lone survivor, U.S. Navy radioman George Ray Tweed, managed to evade the enemy for an incredible 31 months. When American forces invaded in July 1944, he signaled a destroyer offshore and was rescued. His time avoiding the Japanese remains controversial because some Chamorros believed he should have given himself up because many natives were tortured and killed for aiding him during his 31 months on the island.

Ironically, despite the brutality of their Japanese captors, some prisoners empathized with them at war’s end. For others, their hatred remains to this day. After the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Japanese surrendered, the U.S. initiated Operation RAMP, Return of Allied Military Personnel. The book explains the homecoming of many of the prisoners and what become of them after the war. Of the 414 men captured on Guam, about three percent died while held prisoner—a true testament to their tenacity.

The True Story of Catch-22: The Real Men and Missions of Joseph Heller’s 340th Bomb Group in World War II by Patricia Chapman Meder, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2012, 240 pp., illustrations, photographs, notes, $32.95, hardcover.

The True Story of Catch-22: The Real Men and Missions of Joseph Heller’s 340th Bomb Group in World War II by Patricia Chapman Meder, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2012, 240 pp., illustrations, photographs, notes, $32.95, hardcover.

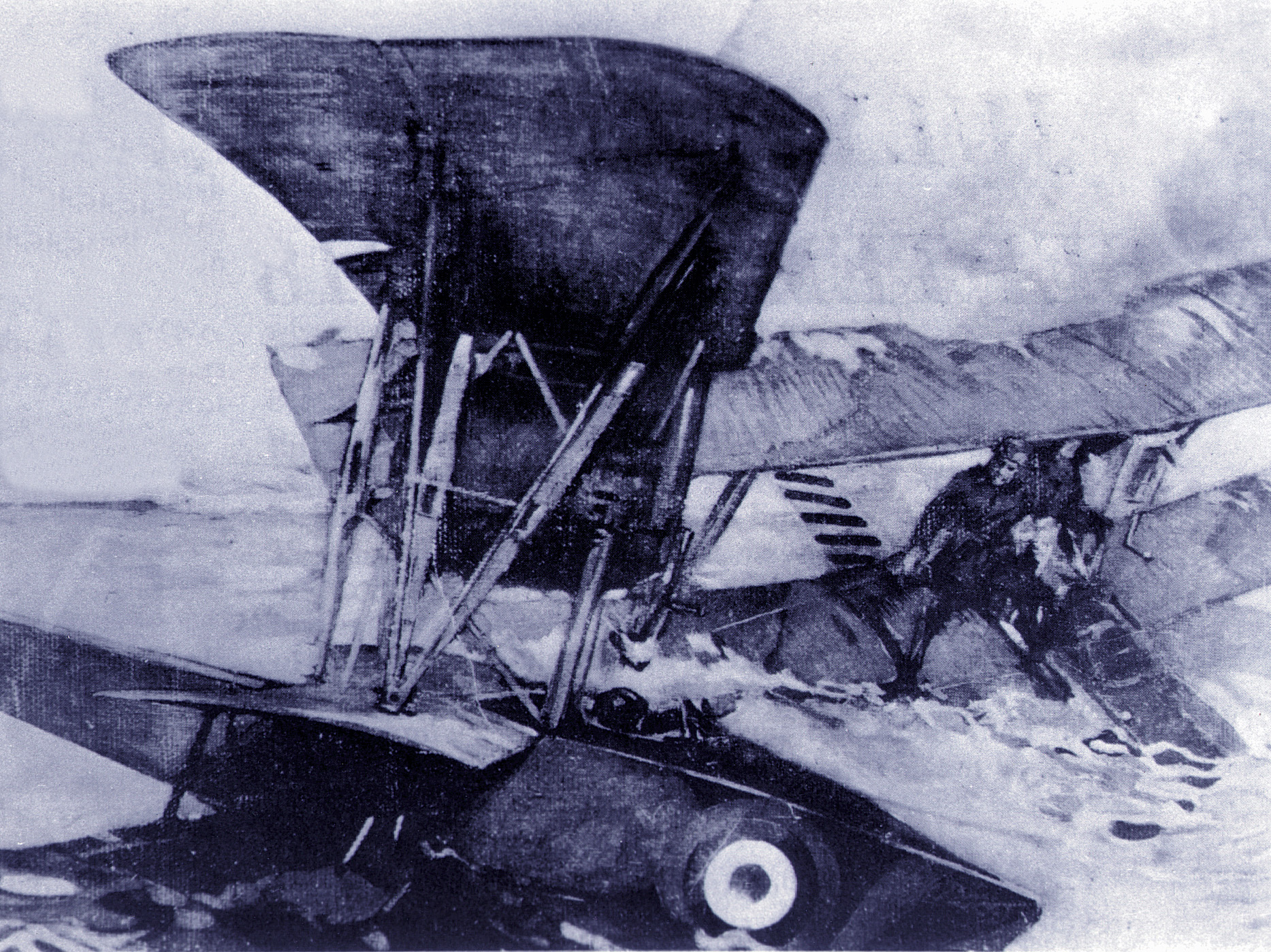

When Joseph Heller’s satirical Catch-22 was first published in 1961, it was hailed as a groundbreaking work in the world of literature. The novel, set in during World War II, concentrates on a B-25 bomber squadron located on the Mediterranean Island of Pianosa. Heller himself was a bombardier with the 488th Bombardment Squadron, 340th Bomb Group, Twelfth Air Force serving in the Mediterranean. Although Heller denied it, to those who served in the unit the similarity between the characters—Colonel Cathcart, Major Major, Brig. Gen. Dreedle, and Captain John Yossarian (based on Heller himself)—was unmistakable.

The author is the daughter of the real-life commander of the 340th Bomb Group, Colonel Willis Chapman, who was “somewhat irritated” when the book first appeared more than 50 years ago. Meder decided to write about the real men who risked their lives to fly countless bombing missions during the war in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations. Most notable is George L. Wells, whom Captain Wren is loosely based on, who flew an incredible 102 missions and passed away in 2010. This is an interesting book that will shed light on the real crew members of the 340th Bomb Group.

New Images of Nazi Germany: A Photographic Collection, compiled and with captions by Paul Garson, McFarland Press, Jefferson, NC, 2012, 496 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $55.00, softcover.

New Images of Nazi Germany: A Photographic Collection, compiled and with captions by Paul Garson, McFarland Press, Jefferson, NC, 2012, 496 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $55.00, softcover.

Once again photo historian Paul Garson has produced a startling volume that lays bare the daily lives of Germans during World War II, both in the military and in civilian life. Through countless hours of research Garson has produced a photographic record of the seemingly mundane activities that might otherwise appear ordinary were they not conducted by a people and a military that supported the most heinous dictator to rise to power in modern times—Adolf Hitler.

Garson describes these images, snapped by both amateur and professional photographers, in detail. Many of these appear for the first time in print. They depict soldiers standing with comrades on the Eastern Front, preparing meals, and manning their weapons. They include civilians embracing their loved ones returning from the front for a brief leave. They include haunting death cards produced by the families of soldiers who have died during their service in distant lands where the Reich stretched its military prowess.

While many of these photos may at first glance seem somewhat ordinary, the simple fact remains that the subjects appear generally as normal people going about their routine. In itself, the fact that these people were integrated into the Nazi machine of repression, murder, and war makes the images disturbing—a phenomenon that keeps the observer from looking away. Garson is also the author of the volume Album of the Damned, which also depicts images of the German military and people during the war years.

War Is Not Just for Heroes: World War II Dispatches and Letters of U.S. Marine Corps Combat Correspondent Claude R. “Red” Canup, edited by Linda M. Canup Keaton-Lima, The University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, 2012, 259 pp., photographs, glossary, index, $29.95, hardcover.

War Is Not Just for Heroes: World War II Dispatches and Letters of U.S. Marine Corps Combat Correspondent Claude R. “Red” Canup, edited by Linda M. Canup Keaton-Lima, The University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, 2012, 259 pp., photographs, glossary, index, $29.95, hardcover.

When World War II erupted, South Carolinian “Red” Canup answered the call. Although 33 years of age and already established as a newspaper reporter and editor, Canup volunteered when he heard that the Marine Corps needed “mature” journalists to cover the conflict in the Pacific as Marine combat correspondents. Brig. Gen. Robert L. Dening was coerced out of retirement by Commandant Thomas A. Holcomb to build a solid core of reporters to cover the action. The group was soon dubbed “Dening’s Demons,” and Canup was a proud member.

After boot camp (despite their ages each man had to pass the same physical requirements that the other younger Marines did), Canup left for overseas and was assigned to the 2nd Marine Air Wing. He covered the Battle of Okinawa and sent hundreds of dispatches during the war describing the conditions and writing about individual Marines. Canup wrote numerous letters to his family as well, which he kept in a cardboard box. His daughter, who edited his material, had the good sense to gather all of it and have it published. This is a real treasure trove for historians about a man who epitomized the word “correspondent,” as well as “Marine.”

Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II by Keith Lowe, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2012, 460 pp., maps, photographs, $30.00, hardcover.

Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II by Keith Lowe, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2012, 460 pp., maps, photographs, $30.00, hardcover.

In May 1945, with the defeat of the Nazi regime in Germany, most of Europe lay in ruins. Thousands of refugees roamed a desolate countryside in not only Germany, but also in France, Italy, Poland, and Russia. With the Nazi loss also came retribution against those who collaborated with the enemy. The basic necessities, such as food, electricity, water, and transportation, were nonexistent in many parts of these countries. Savage infighting took place in Greece and Yugoslavia where brutal murders and pogroms occurred—especially against the Jews. The crime rate escalated, and a thriving black market soon emerged, making fortunes for a few individuals off the millions suffering from the terrible consequences of the aftermath of that war.

Historian Keith Lowe has done a marvelous job of writing about the squalor that most Europeans had to endure at war’s end. While there are countless books describing the campaigns of the war, it seems there are few that tell about the plight of the survivors. Lowe does that quite well with his newest book.

The Last Zero Fighter: Firsthand Accounts from WWII Japanese Naval Pilots by Dan King, Pacific Press, Irvine, CA, 2012, 348 pp., maps, photographs, illustrations, notes, $24.95, softcover.

The Last Zero Fighter: Firsthand Accounts from WWII Japanese Naval Pilots by Dan King, Pacific Press, Irvine, CA, 2012, 348 pp., maps, photographs, illustrations, notes, $24.95, softcover.

What makes this book so absorbing and a cut above the run-of-the-mill ones describing the exploits of Japanese airmen is the fact that the author, Dan King, lived in Japan and can speak as well as write the language. That communication barrier being broken down, he was able to talk one-on-one to five of these survivors and get their unbelievable stories in print.

Perhaps the most intriguing person is the very first, 93-year-old Kaname Harada, who joined the Navy in 1933. In 1936, he took the rigorous exam to become a naval aviator. He graduated first in his class in 1937 and soon saw action in the skies over China. During the Pearl Harbor attack, he flew combat patrols to protect the fleet. He saw action throughout the war and miraculously survived.

King’s book gives the reader glimpses into the minds of the enemy. As he says, they had the same feeling of patriotism and love of family that prompted Allied fliers to perform their duty as well. As one former Japanese airman said: “War is ugly, senseless and cruel. We must never forget.”

Bailout Over Normandy: A Flyboy’s Adventures with the French Resistance and Other Escapades in Occupied France by Ted Fahrenwald, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2012, 286 pp., photographs, $29.95, hardcover.

Bailout Over Normandy: A Flyboy’s Adventures with the French Resistance and Other Escapades in Occupied France by Ted Fahrenwald, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2012, 286 pp., photographs, $29.95, hardcover.

Move over Errol Flynn. There is another swashbuckler who flew with the 486th Fighter Squadron during World War II, and his name was Ted Fahrenwald. His incredible adventures after ejecting from his fighter plane during the war are the stuff movies are made of.

As a youth in rural South Dakota, Fahrenwald grew up learning to fish, hunt, and track. He developed a love for flying and quickly enlisted in the Army Air Forces, graduating as a fighter pilot in 1942. On his 100th combat mission two days after the Normandy landings, his luck ran out. His P-51 Mustang was struck by flying debris when the South Dakota native destroyed a truck. Bailing out, he was lucky enough to be assisted by the French Resistance, or the Maquis. Captured by the retreating Germans, he made his escape and began his perilous journey back toward Allied lines. Resistance fighters with code names such as The Flea and Cesar and French citizens risked their lives to help the downed airman get to safety.

This is an incredible tale of an American pilot with a devil-may-care attitude who persevered and was still able to find humor, even in the most dangerous of times.

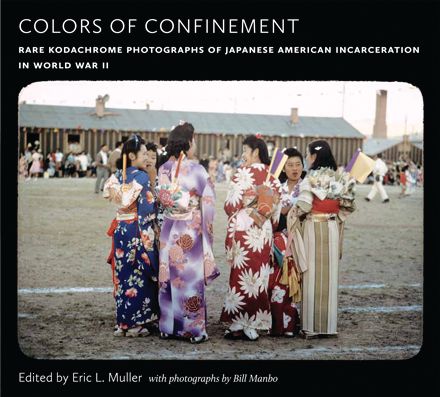

Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II, edited by Eric L. Muller with photographs by Bill Manbo, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2012, 122 pp., photographs, index, $35.00, hardcover.

Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II, edited by Eric L. Muller with photographs by Bill Manbo, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2012, 122 pp., photographs, index, $35.00, hardcover.

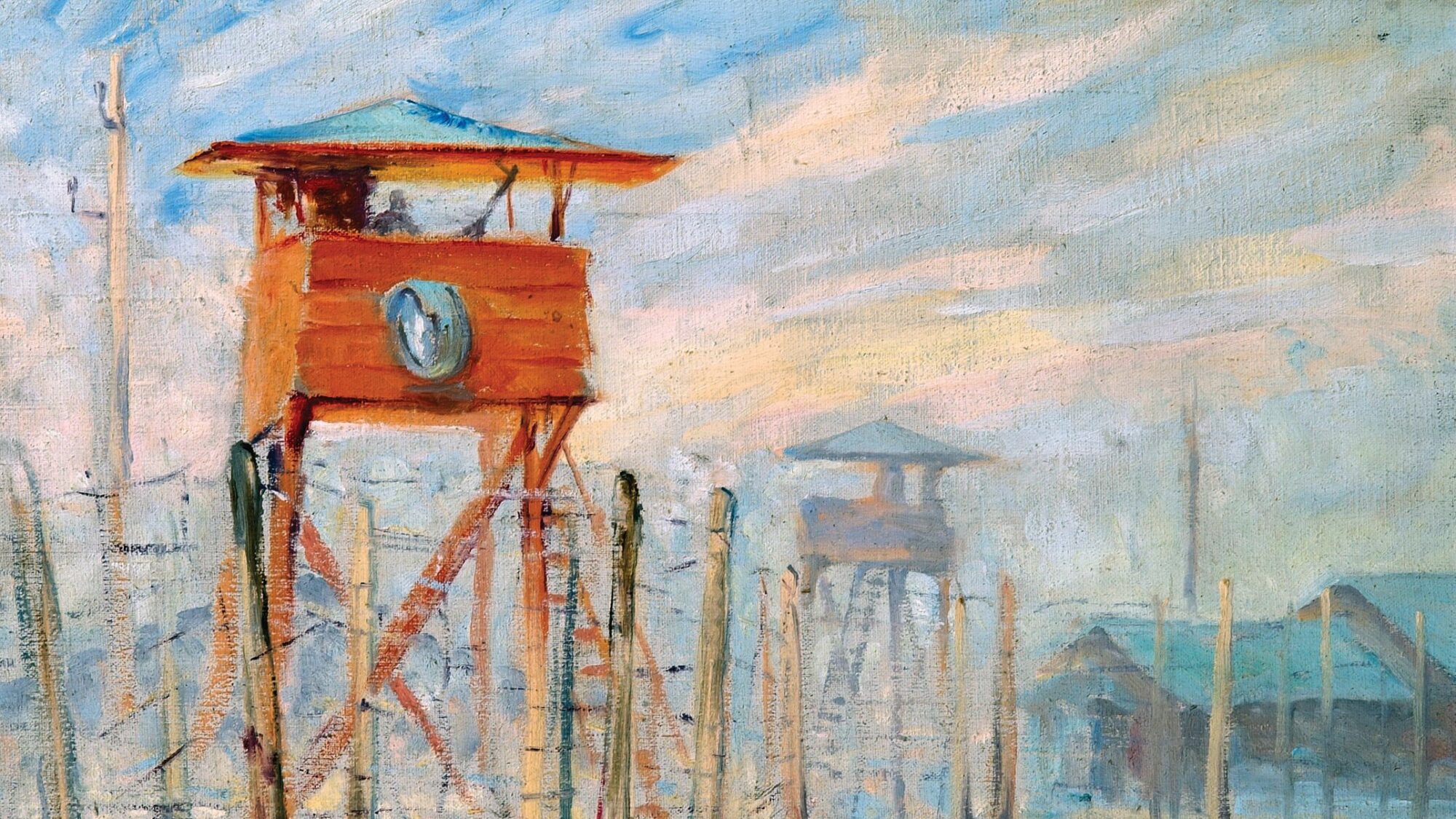

This is a stunning pictorial history depicting the internment of Japanese-Americans at the Heart Mountain detention camp in Wyoming, about 60 miles from Yellowstone National Park, from 1942-1945. The desolate, barren area was one of 10 internment camps where Japanese-Americans were sent because they were deemed potentially disloyal by the U.S. government after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Billy Manbo, a resident of the camp, took dozens of color kodachrome photographs of life within the barbed wire community. His pictures of everyday events are vibrant and depict the social activities and family life, as well as the solitary confinement and desperation many felt when their loyalty to the U.S. was questioned. The color pictures are breathtaking, crisp, and incredible, providing an intimate view of what it was like to live there as an internee.

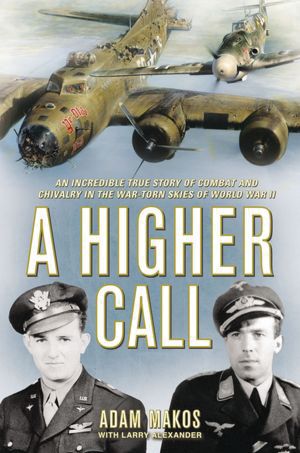

A Higher Call: An Inspirational Story of Combat and Chivalry in the War-Torn Skies of WWII by Adam Makos with Larry Alexander, Berkley Books, New York, 2012, 400 pp., photographs, notes, index, $26.95, hardcover.

A Higher Call: An Inspirational Story of Combat and Chivalry in the War-Torn Skies of WWII by Adam Makos with Larry Alexander, Berkley Books, New York, 2012, 400 pp., photographs, notes, index, $26.95, hardcover.

Despite being embroiled in bitter combat as pilots on opposing sides during the war, Charles Brown and Franz Stigler have something in common. They were both humanitarians first. Stigler, especially, when he deliberately disobeyed orders and saved the lives of Brown and his crew when their badly damaged plane was trying to fly back to England.

On a mission over Germany in December 1943, Charlie Brown was piloting his B-17 Flying Fortress “Ye Old Pub” when it was riddled with antiaircraft fire from German batteries below. Severely damaged, Brown struggled to get his aircraft back to England. Suddenly, a German Me-109 appeared out of nowhere and the crew of the “Ye Old Pub” knew they would be shot down. Amazingly, the pilot of the plane, Franz Stigler, did something extraordinary—he looked at Brown and motioned him onward toward the English Channel as he provided escort.

Limping back to base, Brown was told to say nothing about the incident. Stigler, fearing repercussions because he did not down the bomber, also kept silent. It was not until 40 years later that both men opened up about the experience, a moving story about a heroic and humane act performed during a war that was filled with hatred and bitterness.

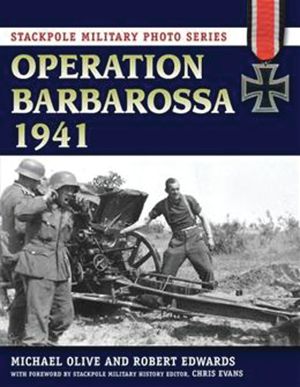

Operation Barbarossa, 1941 by Michael Olive and Robert Edwards, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2012, 200 pp., maps, photographs, notes, $24.95, softcover.

Operation Barbarossa, 1941 by Michael Olive and Robert Edwards, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2012, 200 pp., maps, photographs, notes, $24.95, softcover.

This is an excellent pictorial essay and overview of one of the bloodiest campaigns in World War II—Operation Barbarossa—Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union. The multi-pronged assault saw the German blitzkrieg push deep into Russia in June 1941. The Northern Army Group advanced toward Estonia and Latvia, the Center Group pushed inland and captured Smolensk and moved on Moscow itself, while the Southern Army rolled toward Kiev and the Ukraine.

The book contains dozens of photographs illustrating the horror of the combat and its effects on the soldiers as well as the civilian population. In the center of the book are color photos of the uniforms, weapons, and other articles worn and used by each combatant.

Although it achieved some early success, the German juggernaut came to a screeching halt when they overextended their supply lines. They also did not count on the severity of the Russian winter. Running short on the essentials, the German Army was forced to retreat as the Red Army nipped at its heels all the way back to Germany. Hitler should have studied his history a little more carefully and read about Napoleon’s disastrous foray into Russia nearly 150 years earlier.

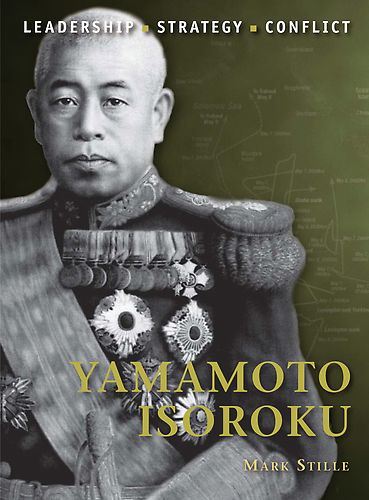

Yamamoto Isoroku by Mark Stille, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2012, 64 pp., maps, illustrations, photographs, index, $18.95, softcover.

Yamamoto Isoroku by Mark Stille, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2012, 64 pp., maps, illustrations, photographs, index, $18.95, softcover.

An interesting and thought-provoking look at the man who masterminded the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, this book describes the life and career of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. Retired U.S. Navy Commander Mark Stille delves into the decisions Yamamoto made while commanding the Japanese fleet. Although Yamamoto was revered in his own country, Stille criticizes Yamamoto’s strategy and states he “was no military genius.” His negligence in expanding Japan’s air arm and constructing adequate airstrips once they occupied an island is evident, as he only envisioned the air force as a “raiding force.”

“For all his gifts,” Stille writes, “Yamamoto could not rise above the system that created him. A truly great leader could have taken control of the situation he was faced with, but Yamamoto never seemed able to do this.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments