By Nathan N. Prefer

When the men of the newly arrived 106th Infantry “Golden Lions” Division arrived on the front lines near St. Vith in Belgium on December 11, 1944, they were happy to learn that they were inheriting a quiet sector. The combat-experienced veterans of the 2nd Infantry Division had told them so. Even when Pfc. Earl Copenhaver pulled the lanyard of his 105mm howitzer of Battery A, 589th Field Artillery Battalion, firing the division’s first shot in anger, the lack of any response from the enemy only enhanced the feeling that the new division had “lucked out” by starting its combat career in a quiet sector of the front line.

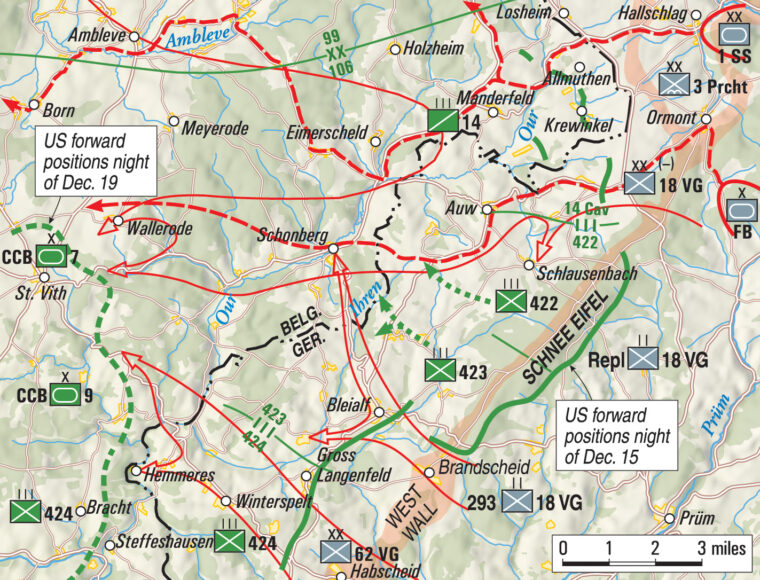

The division’s three infantry regiments and four artillery battalions took over the positions formerly held by the 2nd Infantry Division, noting in passing that most of these had been German positions that the Americans had simply taken over when they drove the enemy out several weeks earlier. The division’s organic engineers, the 81st Engineer (Combat) Battalion also took over frontline positions, and the division’s flank was guarded by the 14th Mechanized Cavalry Group. The attached 168th Engineer (Combat) Battalion was in the division’s rear, maintaining roads, supply depots and other tasks.

The men of the Golden Lions may not have been aware of it, but their division was guarding a 22-mile stretch of the Allied front line in Northwest Europe. The recommended length of front line for an American division in 1944 was at most six miles. Even the attached units, including the 14th Cavalry Group, 168th Engineer (Combat) Battalion, and 275th Armored Artillery Battalion, could not make up the strength to properly cover such an extended front. Although a few senior officers may have been concerned, most were not as this was, once again, a quiet sector where nothing much was expected to happen.

There were other difficulties as well. The division artillery battalions were low on ammunition, having received none since landing in France a week before. Assured that they would receive plenty of ammunition when they arrived at the front, in fact there was none for them. It was only through the generosity of the artillery battalions of the 2nd Infantry Division, that a supply was finally obtained. But, of course, that was not a serious problem in such a quiet sector. Of more concern to the men of the Golden Lions was the fact that their barracks bags, containing all their spare clothing and personal articles, had yet to catch up with them. In the cold, wet climate of the Ardennes Forest, this quickly became a problem when individual cases of frostbite began to appear within days of arrival.

The climate was not welcoming, and the men huddled in huts, pillboxes, and villages when available. Most of these villages were in depressions, “sugar bowls” the men called them, at crossroads within the Ardennes Forest. They were all surrounded by hills which would allow an enemy unobstructed observation of them and easily allow an enemy to bring down fire on each village.

The division commander was worried about the way his division had been ordered to position itself. Major General Alan Walter Jones was born in Washington State in 1894. After attending the University of Washington, he accepted a commission in the Infantry in 1917 and made the Army his career. Although he had never seen combat, his training at the Command and General Staff School and Army War College told him that his division was vulnerable to an enemy attack. His assistant division commander, Brigadier General Herbert Towle Perrin, agreed with his concerns, as did the division’s artillery commander, Brigadier General Leo Thomas McMahon. Even more outspoken was Colonel Mark Devine, commanding the 14th Mechanized Cavalry Group, who insisted that a new plan be drawn up to prepare for a counterattack. With all the senior commanders in agreement, the order was issued to develop such a plan.

The division’s intelligence officer, Lieutenant Colonel Robert P. Stout, noted that the division faced two known enemy divisions, the 18th Volksgrenadier Division and the 26th Volksgrenadier Division. This information came from the division’s senior headquarters, the VIII Corps, First U.S. Army. Both enemy formations were inexperienced and had been destroyed on other fronts before being rebuilt with transfers from the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe. There were also supposed to be two panzer divisions some 15 miles behind enemy lines that could counterattack, although that seemed unlikely in the wooded and hilly terrain held by the 106th Infantry Division.

As the planning continued, the Germans remained quiet except for the occasional artillery or mortar shelling and patrol activity. None of this disturbed the Golden Lions as much as the sounds each evening of engines behind enemy lines. No one seemed to be able to account for the motor traffic, what it was or what it meant. When one battalion intelligence officer reported hearing a “motor convoy” to VIII Corps, he was informed that the Germans were playing with the newcomers by playing transcriptions over loudspeakers to make them nervous.

Despite this calming news from VIII Corps, Colonel Stout ordered increased patrols to better identify the enemy opposite the 106th Infantry Division, plot enemy minefields, and capture prisoners. Just as this was to begin, overshoes for the suffering infantrymen arrived to improve their situation. And one patrol nearly found out what the Germans were really doing behind their front lines. A patrol from Troop C, 18th Mechanized Cavalry Squadron, under First Lieutenant Ajax L. Crawford, was prowling behind enemy lines on the night of December 15-16 when they noticed a lot of activity in the village of Allmuthen. Lieutenant Crawford and his eight men investigated and discovered the village filled with the enemy busy preparing weapons and vehicles for some sort of action. Before they could see more, they bumped into an equally surprised German patrol and had to withdraw.

General Jones and his staff had good reason to be concerned. Across the front line the Germans were gathering 30 divisions, 1,900 artillery pieces, and 970 tanks and armored assault guns. These were being assembled for a massive counterattack whose goal was no less than cutting through the Allied front lines and reaching the critical port of Antwerp, Belgium. Success would divide the British 21st Army Group (2nd British and 1st Canadian Armies), the Ninth U.S. Army and part of the First U.S. Army from the rest of the Allied forces to the south. The hope was that such a success would force a negotiated peace upon the Western allies. The idea came from the highest authority in Germany, Chancellor Adolf Hitler, and every effort was being made to carry the plan to success.

Facing the 106th Infantry Division and 14th Mechanized Cavalry Group was the Fifth Panzer Army under the command of General Hasso Eccard von Manteuffel, a respected and experienced battlefield commander. His plan was for General Walther Lucht’s LXVI Corps to use Major General Hoffman-Schönborn’s 18th Volksgrenadier Division to encircle the Golden Lions on the high ground known as the Schnee Eifel and isolate them while the rest of the Fifth Panzer Army raced to the west. Only a few men from the 18th Volksgrenadier Replacement Battalion would hold the front lines while the rest of the division attacked around the flanks of the Americans. An assault gun battalion would support the German attack. H-Hour, set for the morning of December 16, was to open with no massive barrage, but surprise was to be used to gain and pass the flanks of the American positions. The attack was to be supported by Major General Frederich Kittel’s 62nd Volksgrenadier Division, brought up from reserve.

The attack began as planned at 5:30 a.m. on December 16, 1944. Enemy shells fell on crossroads and towns behind the 106th Infantry Division’s front. The frontline infantrymen took cover, the division band put away their instruments and took up positions as the headquarters security guard, and the division braced for an attack. One witness remembered, “At 6:15 the shelling stopped. Vague figures in white snow suits, figures who screamed and whooped as they danced through the trees, flittered along the front. The clatter of tank treads reverberated on the roads. At last this was something tangible, American artillery, mortar, machine gun and small-arms fire came down on the enemy spearheads.”

The attack on the 14th Mechanized Cavalry Group surprised the Germans as much as the Americans. So dispersed were the cavalry positions, that at first the Germans believed that the Americans had pulled back before they attacked. But they soon learned differently, for when they attacked the villages the cavalry held, they were repeatedly repulsed. In the case of the village of Krewinkel, a platoon of Troop C and the reconnaissance platoon of Company A, 820th Tank Destroyer Battalion fought off attacks for hours. These attacks from the 3rd Parachute Division were unsuccessful, and the Americans continued to hold the village. After the last unsuccessful attack, the Germans withdrew, shouting to the Americans, “Take a ten-minute break. We’ll be back,” to which one GI responded, “We’ll still be here.”

But the German strength was overwhelming and supported by armor and artillery. They would not be denied for long. Soon individual cavalry troops were cut off and surrounded. Some surrendered, others tried to escape, some successfully, others not. Colonel Devine called up his reserve cavalry squadron, the former Chicago “Black Horse Troop” and now the 32nd Mechanized Calvary Reconnaissance Squadron under Lieutenant Colonel Paul A. Ridge, but it could do little in halting the enemy advance. By December 19, the 14th Mechanized Cavalry Group consisted of small groups of men trying to reach American lines and avoid capture. Colonel Devine, overcome by the destruction of his command, collapsed and was relieved of command. Lieutenant Colonel William F. Damon, Jr., the commander of the 18th Mechanized Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, assumed command of the remnants of the 14th Mechanized Cavalry Group.

Unknown until after the battle, the 14th Mechanized Cavalry Group had been caught on the boundary between the attack of the Sixth Panzer Army’s 3rd Parachute Division to the north and the Fifth Panzer Army’s 18th Volksgrenadier Division on the south. Given the wide dispersal of its units, required to cover such a vast front, it never had a chance of accomplishing its mission to maintain contact between the V and VIII Corps. In attempting to do so, it lost 20 percent of its officers, 33 percent of its enlisted men, and 53 percent of its vehicles.

Meanwhile, the Germans had penetrated deeply behind the Golden Lions’ front lines, slipping between the 422nd Infantry and 14th Mechanized Cavalry Group on one side and between the 424th Infantry and 106th Reconnaissance Troop, which was all but wiped out, on the other. Soon the Germans were behind the main line of resistance, cutting off supplies, communications, and withdrawal routes. By the end of December 16, General Jones had committed every resource except the attached 168th Engineer (Combat) Battalion. His 422nd and 423rd Infantry Regiments were surrounded on the Schnee Eifel while his 424th Infantry was fighting for its life nearby. He called for help from VIII Corps. Help from combat commands of the 7th and 9th Armored Divisions was promised.

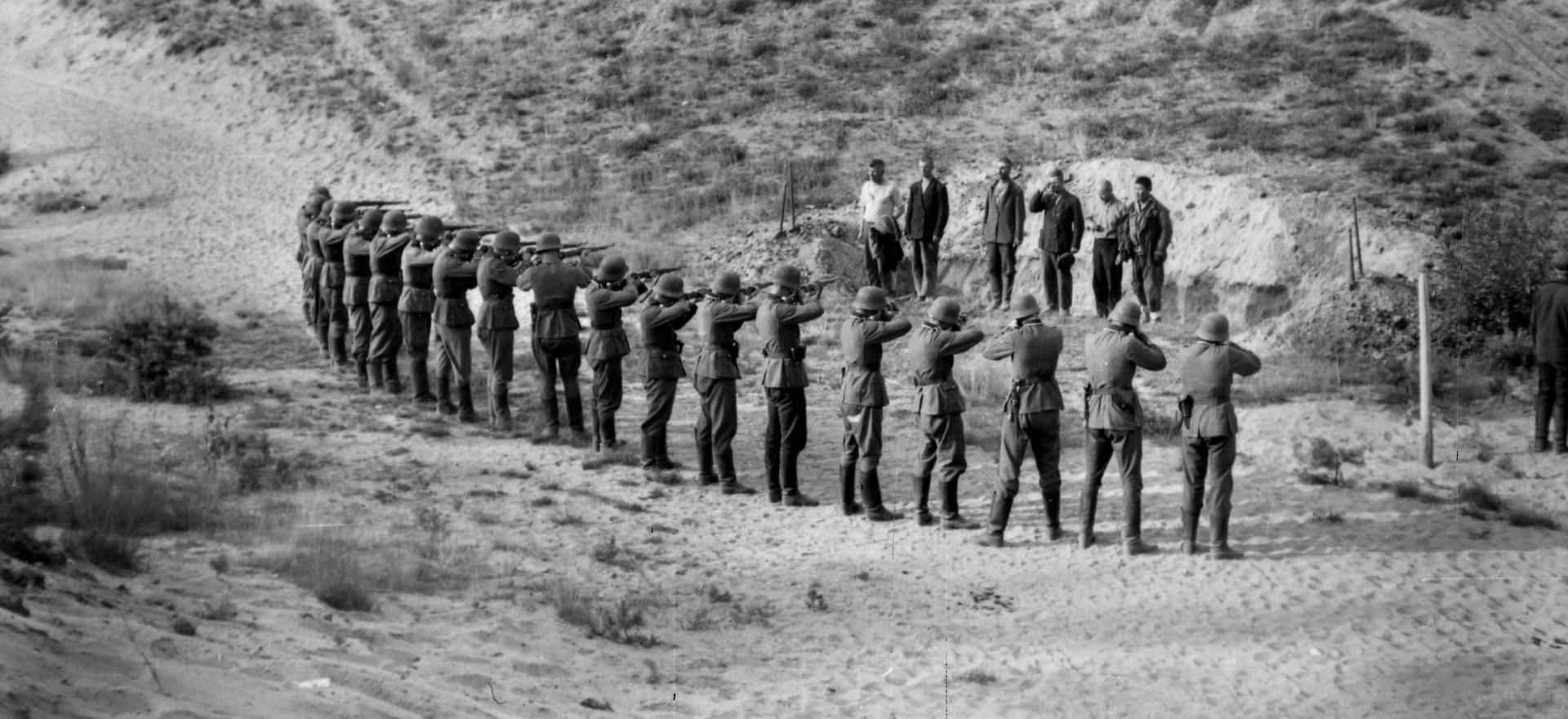

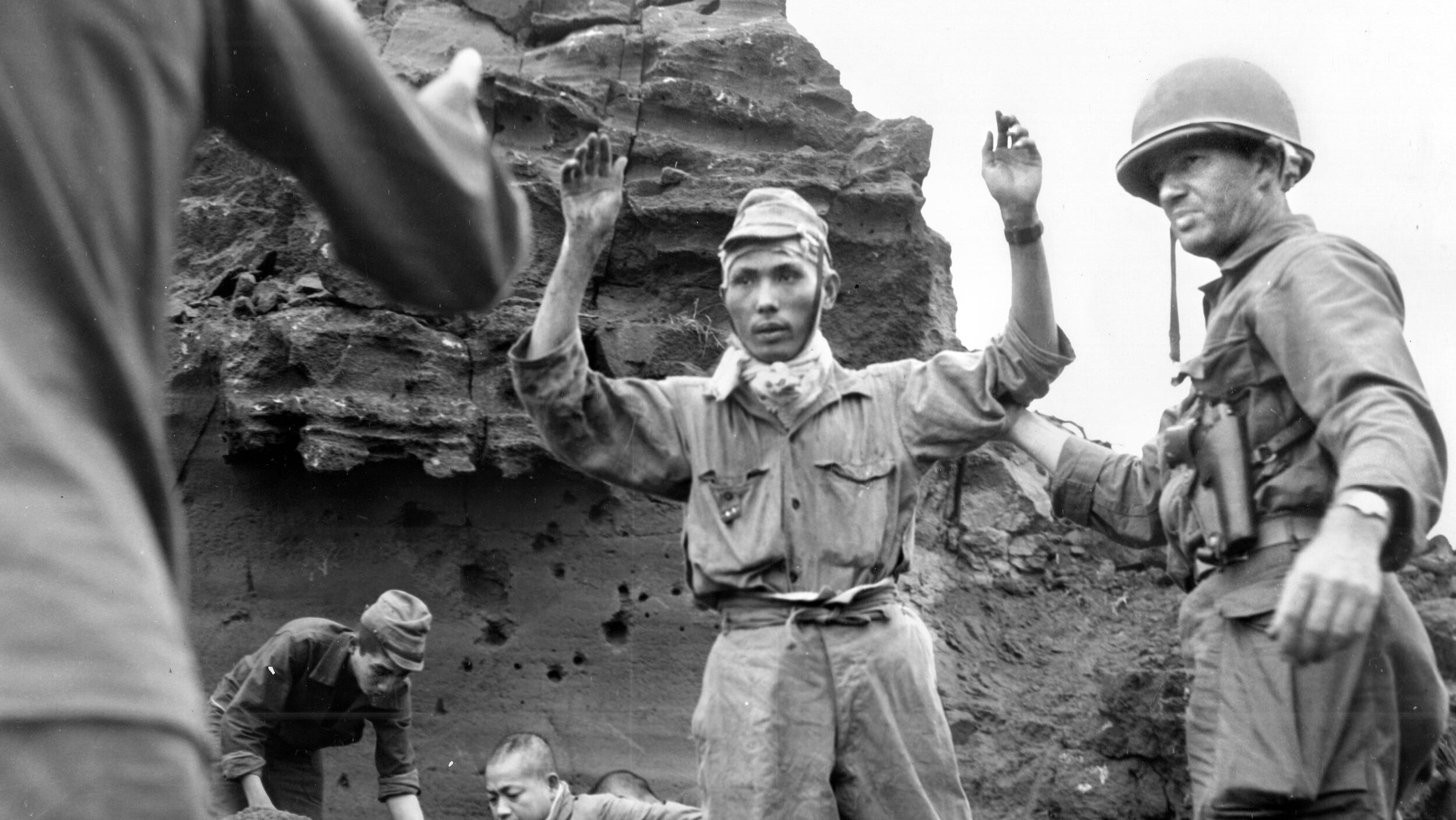

It was too late. By the end of December 17, perhaps as many as 9,000 American soldiers were trapped on the Schnee Eifel, including the 422nd and 423rd Infantry Regiments, parts of the 589th Field Artillery Battalion, the 590th Field Artillery Battalion, Company B, 81st Engineer (Combat) Battalion, Company C, 820th Tank Destroyer Battalion, and others. Attempts at air resupply had failed. The reinforcements sent by VIII Corps were too weak to break through to them. German tanks were moving closer. They had no choice but to surrender.

But that was not the end of the Golden Lions. Although the bulk of the division had been surrounded and forced to surrender, the rest of the division fought on. The 424th Infantry Regiment would go on to fight the rest of the month with the equally badly hurt 28th Infantry Division on its flank. It would later constitute the core for rebuilding the division, which returned to battle in 1945. Others fought on despite having lost all support and with no orders on what to do next. One such unit was Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Paine Kelly, Jr.’s 589th Field Artillery Battalion, one of three 105mm howitzer battalions that were a part of the 106th Infantry Division. The battalion was in position two miles northwest of Schlausenbach supporting Colonel George L. Descheneaux’s 422nd Infantry Regiment when the attack began. Its positions were along Skyline Drive and ran some 300 yards from Bleialf to Auw. The three firing batteries were spread out along the road in woods and road junctions. They were kept busy responding to calls for support because the 422nd Infantry Regiment lacked any mortar ammunition, which would have otherwise been used in most cases. Once the attack began the 589th Field Artillery Battalion sent out local patrols for its own protection. One patrol soon reported enemy infantry approaching from the direction of Auw.

The 589th Field Artillery Battalion was organized at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, as a truck-drawn 105mm howitzer battalion. Assigned to the 106th Infantry Division, it trained there until it departed the United States in November 1944, for England. Like the rest of the division, it landed in France December 6, 1944, and was soon on the front lines. The September 1943 Table of Organization and Equipment for the battalion included 31 officers, two warrant officers, and 488 enlisted men. Besides two aircraft for observation, the equipment included 12 105mm howitzers, 21 .50-caliber machine guns, 37 trucks, 19 weapons carriers, and 22 jeeps.

The battalion’s main weapon was, of course, the 105mm howitzer. With this it provided artillery support for the infantry in attack or defense. Developed in the 1920s and 1930s, the 105mm (3.0-inch) howitzer weighed 4,475 pounds and fired a high explosive shell weighing 33 pounds. It had a maximum range of 12,248 yards, had a split trail, hydro-pneumatic recoil system and was known in the U.S. Army as the M2A1 howitzer.

The battalion now heard enemy fire coming from the left and rear of its positions. Enemy counterbattery fire and distant small-arms fire began to impact within the battalion’s area. First Lieutenant Thomas J. Wright, Jr., executive Officer of Battery C, moved forward to an observation post of the 634th Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion and adjusted fire on approaching enemy assault guns. Meanwhile, Major Elliot Goldstein, the battalion executive officer, took two bazooka teams from the nearby 592nd Field Artillery Battalion and led them to the front to support the 634th AAA Battalion. Soon enemy tanks were reported behind the regiment and the artillery battalions.

The enemy tanks came into view, and Captain George F. Huxel, the battalion assistant operations officer, tried to take them under fire, but they were too close and opened fire on the battalion. One of the outposts opened fire, supported by 40mm fire and bazookas, which damaged the armored vehicle. Finally, Battery A managed to position its guns and fired two devastating rounds which finished off the enemy assault gun.

Another tank opened fire, and Major Goldstein and Captain Arthur C. Brown, the commander of Battery B, directed fire which silenced this vehicle as well. First Lieutenant Eric Fisher Wood, Jr., Battery A’s executive officer, ran to a nearby hill and, shouting instructions back, directed Number 4 gun’s fire, hitting the vehicle. Lieutenant Wood then ordered his guns to fire short-fuse shells into the woods to clear out any enemy infantry hiding there. These acts broke up the enemy attack on the 589th Field Artillery Battalion. But the Germans had now blocked the withdrawal route of Battery C.

By late afternoon, the Germans held Auw in strength, the cavalry had withdrawn on the flank, and Lieutenant Colonel Roy Udell Clay’s 275th Armored Field Artillery Battalion was also pulling back. Soon orders came from General McMahon for the 589th and 592nd Field Artillery Battalions to withdraw as well. Intense activity erupted in the artillery battalions as preparations were made to get the two battalions on the road. The 589th Battalion was to join its service battery three miles south of Schönberg while the 592nd Battalion headed for St. Vith. The roads were difficult, narrow, snow-covered, and winding through woods from which the enemy might strike at any moment. Each gun had to be carefully maneuvered around sharp curves on icy roads while enemy fire buzzed overhead. Most difficult was the situation of Battery C, whose retreat route was cut off by the enemy.

Battery A discovered that the wheels of some of their guns had sunk up to their axles into the muddy ground. But after much effort, both Battery A and B were ready to travel. Lieutenant Wood had by now succeeded to command of Battery A after its commander, Captain Aloysius J. Mencke, had been captured at a forward observation post. As they struggled to the rear, they were unaware that reports were coming into division headquarters from the 32nd Mechanized Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron that they had been pushed out of Schönberg and were withdrawing. Other reports indicated the enemy was on the Schönberg Road and establishing roadblocks behind the forward American positions. General Jones ordered the 81st Engineer (Combat) Battalion withdrawn to St. Vith and the 806th Ordnance Company evacuated.

The 589th Field Artillery Battalion was struggling to withdraw as ordered. The enemy shelled their wooded area as they hitched the guns to their prime movers. The road was a morass of mud and ice that required the most careful maneuvering. But soon both Batteries A and B were on the road. Lieutenant Colonel Joseph F. Puett’s 2nd Battalion, 423rd Infantry, tried to assist Battery C out of the area by attacking the Germans at the roadblock and woods, but General Jones had marked them as a division reserve, and he did not want them tied down yet, so permission was denied.

Colonel Puett would later report that only with the aid of a bulldozer and daylight could they have released the Battery C howitzers from the mud, but neither was available. Colonel Kelly asked for and received permission to destroy the Battery C howitzers. He then led the men to the point where they were to meet the trucks which would carry them to the rear. Along the way most of the men of Battery C were captured by the enemy. Attempting to escape by cutting across the wooded hills, the battery commander, Captain Rockwell, was killed. Colonel Kelly managed to return to Colonel Puett’s infantry battalion, where he would share their fate.

The two-battery battalion managed to reach the main road and withdraw, losing another howitzer when it slid off the icy road and had to be abandoned. They were just setting up their guns east of Schönberg when firing began nearby. Lieutenant Wood ordered one gun under Sergeant Barney M. Alford to set up on the road in an antitank defense. Meanwhile, service battery, further up the road, was attacked by the enemy. They fought back from houses and roadside ditches. Pfc. Thomas C. Graham raced across an open, fire-swept space to reach a machine gun, and opened fire. Using bazookas, small arms, machine guns, and grenades, they held back the Germans, capturing an officer and several enemy soldiers. But as before, the enemy soon overwhelmed service battery, and the men scattered for safety. The 589th Field Artillery Battalion, what was left of it, was now surrounded by the enemy. The executive officer, Major Arthur C. Parker, Jr., in command after Colonel Kelly’s disappearance, ordered each remaining battery to get out as best it could.

Battery B was overrun before they could get out, but Lieutenant Wood managed to get three of his howitzers on the road. Under small-arms and tank fire, the battery roared down the highway toward St. Vith. The men of Battery B followed behind in trucks. The column suddenly came upon an enemy tank, and Lieutenant Wood ordered the column to halt while he and a small group attacked the tank with a bazooka and carbines. The tank disappeared. They again rolled on the highway until a second tank blocked their way. The tank blew up the lead truck. The artillerymen took to the woods, encountering an officer and seven artillerymen from the 333rd Field Artillery (Colored) Battalion who were similarly stranded in front of the tank. Lieutenant Wood refused to surrender and took off for the nearby woods, from which he would later fight an epic battle alone behind enemy lines. Battery B and the remnants of service battery were overrun and scattered. Many were captured; others managed to rejoin American lines later in the battle.

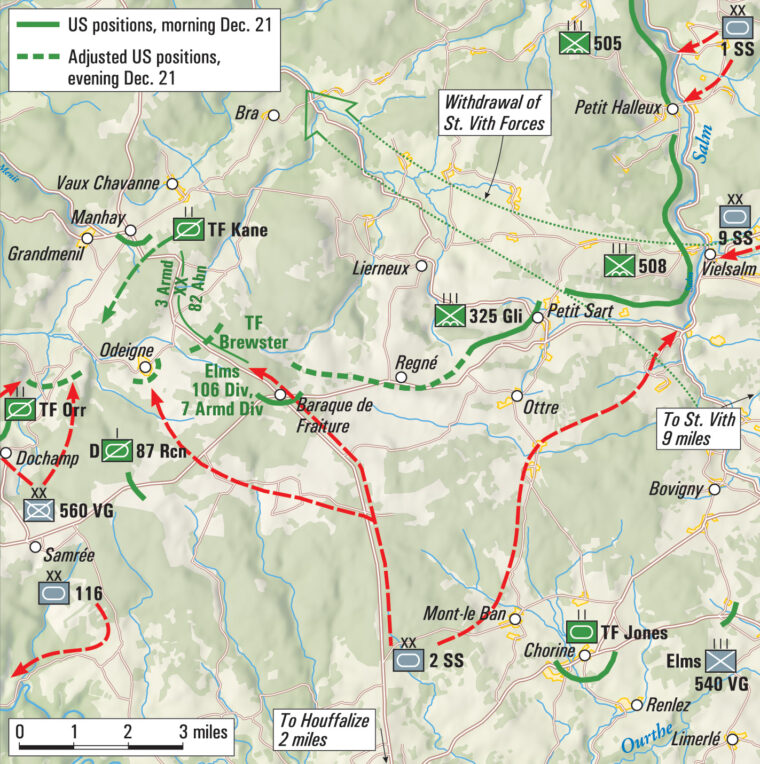

But the three guns of Battery A that Lieutenant Wood had pushed down the road survived. They had moved through Schönberg under fire, picked up service battery of Lieutenant Colonel Vaden Lackey’s 590th Field Artillery Battalion (105mm howitzers) and prepared to move north to find a place to stop and fight again. They would make their stand at a place soon to be known as “Parker’s Crossroads.”

Its true name was Baraque de Fraiture, a height on the highway between Bastogne and Liége. “It consisted then, as it does today, of a few buildings on one of the highest summits in the Ardennes (over 2,000 feet), and a key intersection of the north-south road from Bastogne to Liége with a good east-west route running between Vielsalm and La Roche,” said one observer. It was an important road, since from it one can travel to Basel, in Switzerland, to Amsterdam, in Holland and to Sedan in France. It was “a dreary, snow-sifted patch in the middle of one of the Ardennes marsh areas, surrounded by pine forests, and lying eight miles in air-line west and slightly south of Vielsalm.”

When the order came to withdraw from St. Vith, Major Parker took the three remaining guns of the 589th Field Artillery Battalion to Baraque de Fraiture with orders to set up a roadblock to protect the Golden Lions’ rear. He arrived on December 19 with about 100 men, all exhausted and numb from the cold. Here he set up his roadblock. One report has him declaring, “We will run no more. Here we will stand and fight and here we will make a difference.” His command included the three 105mm howitzers, some machine guns, and several trucks. The following day he added to his troop list four halftracks mounting multiple .50-caliber machine guns from the 203rd Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion of the 7th Armored Division. He also added some stray tanks, a cavalry platoon, and a few towed anti-tank guns.

Major Parker’s three 105mm howitzers were commanded by men of the battalion who had managed to escape the Schnee Eifel trap. One gun was commanded by Captain Arthur C. Brown, originally of Battery B. A second gun was commanded by 1st Lieutenant Thomas J. Wright of service battery, and the third gun was under Sergeant Barney M. Alford. Wounded men were treated by battalion medics including T/5 Robert E. Vorpagel and T/4 Melvin R. Pollow, often under fire and utilizing enemy medical supplies to treat both American and German wounded.

Major Parker soon found himself under the command of Colonel Herbert W. Kruger, who commanded the 174th Field Artillery Group. Colonel Kruger was moving his battalions out of the danger zone and wanted Major Parker to protect his rear while he did so. Colonel Kruger also informed Major Parker that enemy tanks were believed to be in nearby Chérain.

No enemy tanks appeared, and Major Parker stripped his command of all his men who were not a part of the firing of the howitzers and sent them to the rear at Vielsalm. At Baraque de Fraiture he organized a perimeter defense with his guns and waited. The Germans did not appear. The artillerymen had no food and were reduced to eating emergency rations, so Major Parker sent his trucks to the division supply area for food, gas, and small-arms ammunition. The trucks returned with orders that the battalion should withdraw and refit in the rear.

But before the guns could be limbered up, new intelligence reported Germans approaching. General McMahon ordered Major Parker to hold his roadblock to protect the division supply area from attack. While waiting, men of the battalion service battery who had survived the Schnee Eifel joined the group, which now numbered about 110 officers and men.

The platoon from the 87th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron soon reported the enemy and tanks in the village of Samrée. Major Parker took them under fire, and after two volleys the reconnaissance observer reported “mission accomplished.” Realizing he might be in place for a while, Major Parker reorganized his roadblock. One howitzer was pointed east, down the road to Regné, the second pointed west, on the road to Samrée, and the third south toward Houffalize. Machine guns were set up around the perimeter. Outposts were put out to give early warning of the enemy’s approach.

Unknown to Major Parker and his little band at the crossroads, the 82nd Airborne Division had been rushed from theater reserve and ordered to form a line of defense just beyond Parker’s crossroads. They were moving into position, but for the moment the airborne division’s right flank was unprotected. If a strong German force came through Parker’s crossroads, it could hit that unprotected flank and possibly knock out the new line of defense before it was completed.

It was midnight on December 19-20 when an outpost reported a dozen enemy motorcyclists coming down the road. While the outpost kept quiet, a .50-caliber machine gun opened fire and scattered the Germans. Soon all outposts were reporting enemy approaching. The battle that followed left six dead enemy and 14 prisoners in Major Parker’s hands.

Morning brought snipers, who harassed the artillerymen all day long. Several men were killed during the day. At noon came word from the headquarters of the 106th Infantry Division that the remnants of the 589th Field Artillery Battalion were to withdraw for reorganization, leaving only the single platoon of the 87th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron to hold the crossroads. Major Parker knew that the lone platoon could not possibly hold the roadblock, so he elected to remain with his men until other reinforcements arrived.

Later that afternoon the 560th Volksgrenadier Regiment attacked again. This time two platoons of tanks from the 3rd Armored Division were available, and the attack was repulsed. But the visiting tanks were only passing through, and Major Parker was again on his own. Then word was received that infantry of the 82nd Airborne Division was coming up to relieve the artillerymen. An advance squad came in and reported that the Germans had built their own roadblock which cut Parker’s Crossroads off from all friendly contact except along the Liége Highway to Manhay. In effect, Parker’s crossroads was now surrounded by the enemy.

Reports of enemy activity in the early morning hours of December 21 raised fears of an attack. Major Parker ordered his artillery and machine guns to open fire in the hope of making the enemy think he was attacking them. No enemy attack materialized. But constant barrages of mortar, small-arms and machine-gun fire kept the roadblock on edge. German artillery was also active. To maintain his small force, Major Parker was everywhere, encouraging his men, inspecting defenses, and refusing to be evacuated after he was wounded by a mortar round on December 21. Months later, after recovering from his wounds, he would take command of a reconstituted 589th Field Artillery Battalion.

Despite his intentions, Major Parker soon collapsed from his wounds, and Major Elliott Goldstein assumed command. The enemy fire continued all day and all night. Enemy patrols infiltrated close to the perimeter boundaries and attacked in strength before dawn on December 22. They were driven off, but not before two prisoners were taken. These men reported that they were from the 2nd SS Panzer Division, a strong armored force with considerable battle experience and a deadly reputation.

The Germans soon added American guns to their arsenal. Four captured 3-inch anti-tank guns were turned on the Americans at Parker’s Crossroads after a platoon of the 643rd Tank Destroyer Battalion had left the perimeter and been ambushed along the road. But messages from both the 3rd Armored Division and the 82nd Airborne Division to “Hold out as long as you can” left Major Goldstein with no option.

To protect his vulnerable flank, Major General James Gavin, commanding the airborne division, decided to send an infantry company to strengthen Major Goldstein’s forces. He sent down Captain Junior R. Woodruff’s Company F, 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, to assist Major Goldstein. The combined force, still less than 300 soldiers, waited throughout a quiet December 22. Unknown to the Americans, the 2nd SS Panzer Division was having trouble getting fuel to supply its vehicles, and without tanks and assault guns no attack on Parker’s crossroads was going to succeed.

By nightfall, enough fuel had arrived to allow the 4th Panzergrenadier Regiment, some tanks, and an artillery battalion to move. Before dawn on December 23 the 2nd Battalion made a surprise attack on the perimeter but was driven off by the glider infantrymen. Captured radios were used to jam American communications, preventing American artillery observers from directing fire. Whenever the Americans did fire, German mortar crews dropped dozens of shells on the Americans, making observation and determination of direction impossible. The 3rd Armored Division sent some infantry and tanks to help, but so close were the Germans that the infantry had to turn back, and only a few tanks arrived to help in the defense.

One unit that did manage to reach the crossroads was Company C of the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion. Attached to the 3rd Armored Division, the company had been sent by the division commander to help hold the vital crossroads. Later an armored task force was also sent to the crossroads under the command of Major Olin F. Brewster. With eight tanks, two halftracks and supply and transport troops along with Company A of the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion, the task force was halted short of the crossroads, and by the time they would have reached it, the crossroads had been overrun. The paratroopers that had earlier reached the crossroads, Company C, 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion, lost 49 men during the fighting.

The Germans were determined to eliminate this thorn in their side, blocking their plans for a rapid advance to the west. In late afternoon enemy artillery began to pound the perimeter for 20 minutes and then two panzer companies and the entire 4th SS Panzergrenadier Regiment attacked. The Americans were outlined by newly fallen snow which made the American tanks easy targets for the panzers. Within an hour Captain Woodruff was asking his regimental commander, Colonel Charles Billingslea, for permission to withdraw. General Gavin’s reply was the same, “Hold at all costs.”

Major Goldstein went to the 3rd Armored Division for help, but before it could arrive the enemy had attacked. As he tried to return to the perimeter, Major Goldstein found his way blocked and joined the 54th Armored Field Artillery Battalion of the 3rd Armored Division. Up the road, his roadblock was under a major attack by tanks, infantry, artillery, and mortars. Within an hour, and despite a desperate defense, the roadblock was overwhelmed. Only 44 of the 116 glider infantrymen who came with Company F escaped to return to the 82nd Airborne Division.

Major Goldstein later recalled, “The principal emotion I felt was anger, anger at myself for not succeeding in extricating my command from the trap; anger at the Germans; anger at the commander, whoever he might be, for not having sooner sent aid to us. Although I had escaped almost certain capture or death, I felt neither happy nor relieved since the men I commanded were being overrun. I thought all our efforts had come to naught.”

But the battle cost the Germans tanks, soldiers, and time. Sergeants Alford and Jordan knocked out two enemy tanks with their howitzer and missed a third tank with their last round of ammunition. The men then withdrew slowly to the command post, firing their carbines as they went. When the artillerymen heard that the glider infantry was withdrawing, they decided to break up into three groups and withdraw as well. Lieutenant Wright led one group down the road toward Manhay and the 3rd Armored Division, but they were pushed back and captured. Captain Brown, despite his wounds, got his group to safety but was himself captured. Captain Huxel remained at the command post with his group until the roof collapsed. Seeing a group of cows dashing about in confusion and terror, they used that as a distraction to make their own escape.

During the rush, T/5 Pollow stopped to give aid to two wounded men. Then the group dragged them along as they made their way to the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment’s positions. Several of the artillerymen remained in and around the command post until surrounded by the enemy, who demanded their surrender. As they came out, several were shot, the others captured. Parker’s crossroads was no more.

The commander of the 2nd Battalion, 2nd SS Panzer Regiment, 2nd SS Panzer Division, SS Lieutenant Colonel Horst Gresiak would later state that the battles at Parker’s Crossroads were “the most violent and the toughest battle that he experienced during the entire war.”

For its stand on the Schnee Eifel and at Parker’s Crossroads the only recognition the 589th Field Artillery Battalion received was not from its own army, but from the French government, which awarded it the unit Croix de Guerre with Gold Star and Streamer embroidered “St. Vith.” Similarly, the 14th Mechanized Cavalry Group’s only recognition came from the Belgian government, which cited it in an Order of the Day for action in the Ardennes. The 81st Engineer (Combat) Battalion was awarded a U. S. Army Distinguished Unit Citation, as was the 634th Antiaircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion.

Units like the 589th Field Artillery Battalion, the 14th Mechanized Cavalry Reconnaissance Group, 81st Engineer (Combat) Battalion and many others had made a difference in thwarting Hitler’s plan to split the Allied front and negotiate a peace agreement. These units, and so many others, had slowed the enemy drive, which depended upon speed, and had cost it valuable time, while expending the Germans’ strictly limited supplies of ammunition, fuel, and armored vehicles at an unstainable rate.

The “quiet sector” held by the Golden Lions had proved decisive after all.

Nathan Prefer is the author of numerous books and articles on World War II. He received his Ph.D. in military history from the City University of New York and is a former Marine Corps reservist. Dr. Prefer is now retired and resides in Fort Myers, Florida.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments