By Stephen D. Lutz

In the winter of 1944-1945, within Belgium’s Ardennes Forest, better known as the launching pad of the Battle of the Bulge, two war crimes were committed. The better known one—the “Malmedy Massacre”—resulted in the deaths of at least 85 defenseless GIs who surrendered. They were herded into a snow-covered field near Baugnez and machine gunned to death. Then the perpetrators walked among survivors, calmly shooting them again at point-blank range. This atrocity made worldwide headlines. One month later, a second, lesser known mass execution occurred. This one, known as the Wereth 11 Massacre, took place at Wereth and involved 11 GIs from the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion. It led to a two-year U. S. Army investigation, from February 1945-February 1947. The Army’s conclusion: Shut the case down, close it up, and keep it, literally, top secret for decades.

Why such a discrepancy in investigating two major war crimes? The first, the Malmedy Massacre, involved all white GIs. The second, known as the Wereth 11 Massacre, involved 11 black GIs. Would the words “white” and “black” have any meaning here? Or were some other factors involved?

The 333rd Field Artillery Battalion got its start on paper on August 5, 1942. A month later it was established at Camp Gruber in Muskogee, Oklahoma. The Army determined the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion would be equipped with M-114 155mm “Long Tom” howitzers and be manned by “colored” troops, according to the Army’s classification at the time.

Camp Gruber reflected America’s racial tensions and attitudes common to that era. The camp was 18 miles outside Muskogee and 61 miles southeast of Tulsa. As the future members of the 333rd filtered into camp they were well aware of “Jim Crow” laws that dictated every facet of African American life, especially in the deep Southern states.

With Oklahoma being more of a border state, the black soldiers were hopeful that they would not be subject to the Jim Crow traditions. Culturally and heritage-wise, the soldiers were two generations removed from slavery. But perhaps they were unaware of an event that had occurred 21 years earlier in Tulsa, in a neighborhood known as Greenwood—an economically thriving, predominantly African American district of private, commercial, and professional businesses.

On May 31, 1921, under exaggerated, grossly out of control half-truths, an African American man was arrested. The purported charge was that he had offended or molested a white woman. Within 24 hours, a gang of white Tulsa residents burned nearly 40 blocks of the Greenwood neighborhood and killed 300 of that neighborhood’s citizens.

Tulsa, along with the help of the State of Oklahoma, acted quickly to minimize and restrict news of the horrific incident, so it did not get much notice in the national press. Twenty-one years following that murderous rampage, many of those arriving at Camp Gruber had no idea the event had occurred.

Two infantry divisions—the 42nd “Rainbow” and the 88th “Blue Devils”—were also activated at Camp Gruber, as it could house 35,000 military residents. When the raw recruits who would form the basis of the 333rd began arriving, they found three swimming pools, a lake for fishing, 10 baseball diamonds, and facilities for basketball, boxing, volleyball, weightlifting, and football. They also found the sentiments of a racially divided region; most of the facilities were segregated. Still, training had to proceed.

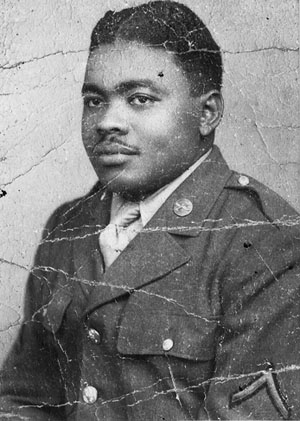

This story focuses on 11 trainees in particular. Tech. Sgt. William Pritchett was from Wilcox County, Alabama. He was born May 5, 1922. He may never have married but was known to have had a daughter. Corporal Mager Bradley, an enlistee, was born April 21, 1917, in Bolivar County, Mississippi. On December 2, 1943, he married 20-year-old Eva Marie James in Muskogee, Oklahoma.

Jimmie Lee Leatherwood was born March 15, 1922, in Tupelo, Mississippi. While living in Texas, he married and the couple had one daughter who would never meet her father. Other members of the 11 were Georgia-born Corporal Robert Green, Private Nathaniel Moss from Texas, and Curtis Adams, a 32-year-old medic from Columbia, South Carolina. He was a newly married GI upon arrival at Camp Gruber and a new father.

At age 36, Tech. Sgt. James Aubrey Stewart was a more seasoned GI. Born in 1906, he had nearly 20 years of pitching baseballs for the Piedmont, West Virginia, semi-pro team, the Piedmont Colored Giants. Many who knew him openly wondered why he never moved forward with the professional Negro Baseball League. He enlisted in the Army in December 1942. His baseball skills were highly prized at Camp Gruber.

Private First Class George Davis was short in stature and was lovingly known by his comrades as “Li’l Georgie.” He was born in 1922 and drafted in May 1942. Before leaving home, Davis took a newspaper picture of Jesse Owens from the 1936 Olympics as an inspiration. Private First Class Due W. Turner was born in Columbia County, Arkansas, on March 11, 1922, but little else is known about him.

Another, more senior veteran soldier was Staff Sgt. Thomas J. Forte who was a cook in the 333rd; he was born in 1915 in Hinds County, Mississippi. Prior to joining the 333rd he had a simple, impoverished wedding on January 19, 1942, in Louisiana. All he could afford was a tin wedding ring. The farthest he got in school was completing grammar school. The last of these 11 was Pfc. George W. Motten, who was born in Texas, but other biographical information is lacking.

These 11 joined 540 other GIs to make up the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion.

A World War II 155mm howitzer battalion, at least according to the manual, consisted of 550 enlisted soldiers and 30 officers. Considering the demands of war, that number sometimes fluctuated.

This structure was divided into five batteries of four guns, or “tubes,” each: Able (A), Baker (B), Charley (C), Service Battery, and Headquarters Battery. According to the Table of Authorization, it took 120 soldiers to fill in a battery and 11 soldiers to efficiently operate a 155mm howitzer that weighed 12,000 pounds. Most typically, a lieutenant colonel commanded a battalion. The 333rd’s commander was 49-year-old Lt. Col. Harmon S. Kelsey from San Bruno, California—a veteran artillery officer who had served in World War I.

As with all African American units in the segregated Army the officers were predominately white. Kelsey, as was also usual, was not happy commanding a mostly black battalion. The overwhelming philosophy for the Jim Crow-era army was that African Americans were inept, undereducated soldiers, incapable of mastering the finer skills and demands of soldiering, and were generally worthless in combat.

Most white officers posted to lead black units found it a dead-end career path. None felt that such a unit, regardless of service and arms, would ever see actual combat. That is where Kelsey stood, and he had no qualms about expressing those sentiments. In regard to the 333rd personnel, he saw them in two colors; green and colored. He told them the only way to get out of the 333rd would be to be killed. In his mind, that would never happen. He was convinced the 333rd would never see combat. In due time this lieutenant colonel would have a major reversal of beliefs about his soldiers.

Most of the 333rd’s other 29 officers were white. The most influential of these junior officers was 21-year-old, Oklahoma-born Captain William Gene McLeod, son of a World War I veteran. At age 16, McLeod joined the Oklahoma National Guard’s 45th Infantry Division, which used to the older style French 75mm howitzer from World War I. He became a sergeant, was eventually accepted into Officer Candidate School, and became a lieutenant in the artillery. In terms of personality, he was every bit the opposite of Kelsey.

One incident stands out. Curtis Adams, the black medic, was visited by his wife, Catherine, and their newborn son. Kelsey avoided the child, refusing to hold the infant. He told the parents an Army camp was no place for a baby, or a mother. But McLeod had no hesitations in cuddling the baby. McLeod saw the privileges of being white, but he stood by his trainees at every step of their training. He believed in his men, and they came to believe in him. Soldiers preferred to approach him over any other officer.

When German prisoners of war arrived at Camp Gruber, Tech. Sgt. William Edward Pritchett was compelled to deliver a concern to his captain. The men of the 333rd noticed the POWs were fed better than the 333rd and that white GIs showed more courtesy and respect for the Germans than to their fellow black comrades. McLeod forwarded those remarks to Kelsey, but they were shooed aside.

The turning point for the 333rd at Camp Gruber came in the summer of 1943. Having spent months fumbling and blundering, with one mishap after another, the men seemed incapable of learning the intricacies of the six-ton weapon. The ultimate goal was to complete a 100-pound shell firing sequence within four minutes before beginning the next firing sequence. But the 333rd trainees themselves felt that was an unimaginable goal to reach. Even worse was Kelsey’s nonstop attitude of the 333rd not being good enough to make it to the front until after the war ended.

During a break on the firing range one summer day, George Davis took to humming a tune his mother often sang to him. Before long his comrades started humming along. The rhythm was off a beat or two, and it took a while to identify the song. It was “Roll, Jordan, Roll,” at which point everybody pitched in with their voices. James Aubrey Stewart found the tune a bit sluggish and suggested speeding the beat up. Then suggestions came for adapting other popular tunes of their times. The overwhelming majority wanted “Roll, Jordan, Roll” kept.

Going back to their firing sessions, the song continued and became a beat by which the men loaded and fired their cannons. Within weeks they came to master the 155mm howitzer, and “Roll, Jordan, Roll” became the battle hymn for the 333rd from then on. Once in France, they would adapt the lyrics, but the basic tune remained.

Prior to leaving Camp Gruber, a few events transpired common to any GI in any war or era. On April 18, 1943, Mager Bradley received a package of edible delights from his wife, Eva Marie, that he was eager to share with his comrades. Within this particular package, however, was a bar of Woodbury soap, which he secreted away, unopened.

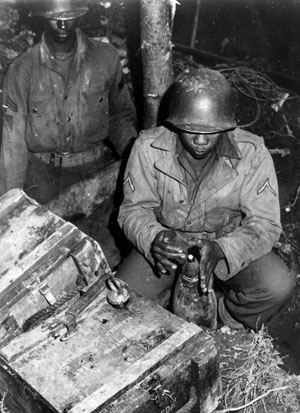

Around that same period, Private Nathaniel Moss showed that he had difficulty throwing a hand grenade. It was a frightening learning experience knowing the consequences of a fumbled toss was having it explode within an arm’s distance. Former baseball player Tech. Sgt. James Aubrey Stewart stepped in with a bunch of baseballs. As a former semi-pro pitcher, he was well noted for his handling of baseballs, so he imparted some of that skill to Moss. After practicing numerous throws with a baseball, Moss was able to toss live hand grenades like a pro.

On February 2, 1944, the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion sailed for England, landing 17 days later. As an independent artillery battalion, it existed as its own entity. Depending on the combat situation, they would be assigned to support units within the VIII Corps of Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton. That meant the 333rd could provide artillery support at any time and anywhere for the 2nd, 4th, and 8th Infantry Divisions and either the 82nd or 101st Airborne Divisions.

On June 6, 1944, the Allies began landing 176,000 soldiers on France’s Normandy coast at landing spots identified as Omaha, Utah, Juno, Gold, and Sword Beaches. It would take six days of massive bleeding, suffering, and deaths to consolidate those beaches before moving inland. When the 333rd FAB arrived on Utah Beach, those bloody scenes were well cleaned up. All seemed settled into a typical naval beach unloading operation.

Once collected, the 333rd found themselves in a familiar slot as an African American unit: nobody wanted them under their feet. Kelsey retained his original sentiments as well.

On the plus side, the 333rd, as an independent artillery battalion within VIII Corps, would be able to move here and there on call whenever big guns were needed. Whether the 333rd realized any differences in those two points or not still meant they would be doing a lot of moving across France to support the divisions within VIII Corps.

Shortly after arriving in France, the 333rd got its first call for a fire mission on behalf of the 82nd Airborne Division besieging Pont-L’Abbé—a 600-year-old city that had a church with a tall steeple. The 82nd’s approach into the city was repeatedly halted by at least one sniper nestled in that steeple. The 82nd had also been taking accurate, well-placed enemy artillery shelling. The steeple afforded an artillery spotter a perfect setting.

Once called, receiving coordinates from nearly nine miles out, the 333rd zeroed in while singing, “Rommel, count your men.” The guns were fired with the second chorus coming, “Rommel, how many men you got now?” Within a span of 90 seconds, four 155mm rounds boomed out, the first being the range finder/marker. The next three precisely hit the church roof and steeple. In answer to the 333rd’s song, “Rommel” lost at least one, if not two or three men. In turn, the 333rd suffered their first combat injury; somehow, Captain John G. Workizer was seriously wounded by friendly fire.

Another event took place during this same period. Since June 6, 1942, the U. S. Army had been publishing its own magazine, YANK. It became a weekly presentation to GIs about their world, their home front, and why they were doing what they were doing. It was YANK that introduced its readers to a new cartoon soldier named “Private Sad Sack,” who became a popular character in the magazine’s pages.

As the 333rd commenced its first firing mission that July 1, one of the YANK writers, Sergeant Bill Davidson, was on hand. The 333rd knew of Davidson’s presence but paid little attention to what he was doing. A few months later the 333rd would learn they were featured in an article in YANK.

On July 2, 1944, the 333rd again was called into action. With the 90th Infantry Division now trying to subdue resistance in Pont-L’Abbé, the 333rd supported it as well as the 82nd Airborne. At noon on July 4, 1944, all artillery units in VIII Corps fired their guns on target simultaneously, creating an Independence Day celebration far beyond mere fireworks.

Five days later, the 333rd moved farther south into Normandy, then west toward La Haye-du-Puits on the Brittany Peninsula—a distance of 244 miles—a route that took the 333rd deeper into dreaded hedgerow territory. Those rows of nurtured bushes stood for centuries as boundary markers between farmers’ fields and also as corrals to keep their flocks of cows, sheep, and goats from wandering off.

At this stage the Luftwaffe retained some presence in the air, subjecting American ground forces to aerial assaults. Upon arrival, the 333rd shot down one Messerschmitt Me-109 fighter that was strafing them. Shortly thereafter, three members of the 333rd were laying communication wire and came upon a well-hidden German Tiger tank. The panzer got off two rounds, which only knocked the three GIs off their feet. Rather than flee, one got on the phone and called the 333rd Headquarters Battery, giving marking range.

Charley Battery sent out three 155mm rounds. The first round, as expected, fell short, requiring an adjustment. The second landed directly on top of the tank. The third hit it again, splitting the 54-ton behemoth in two. At that point even the 333rd’s commanding officer, Lt. Col. Harmon S. Kelsey, had to acknowledge his unit’s accuracy and quickness of firing. He gloated that the 333rd was on its way to “setting new records” with that and the previous firing mission against the church steeple.

In the middle of July 1944, the reality of war sank in. Captain Workizer died from complications of his abdominal wounds, and Private James Erves also died during a firing mishap when one of the big guns’ recoils struck him.

By the end of July, the 333rd had tagged along with the 90th Infantry Division to Saint Sauver-Lenden and back to Saint-Aubind d’Aubige, where they settled alongside the 4th Armored Division.

In that area, although not an antiaircraft unit, the 333rd knocked down several more planes. They also started collecting prisoners of war. Arriving at Rennes, the 333rd shared shooting time with the 8th Infantry Division artillery while singing out, “Stand Back! Ready! Rommel, count your men! Fire! Rommel, how many men you got now?”

All across the VIII Corps area of operations adulation was coming the 333rd’s way. More and more infantry units vied for their support, knowing their quickness to fire, adjust, fire again, and how few rounds they needed to expend before hitting the mark.

At some point as they gained proficiency, the 333rd fired off three 155mm rounds from one tube within 45 seconds, while it took most other crews three to four minutes to fire just one round.

It was time to move again, this time to Saint-Malo, France, a 2,000-year-old fortress city on the coast of the Brittany Peninsula, most often referred to as Saint-Malo Citadel. The 83rd “Thunderbolt” Infantry Division had already lost one battalion while attempting a traditional frontal assault on the town. On August 13, 1944, the 333rd arrived and set up its guns 10,000 yards—5 1/2 miles––from the massive walled city that encompassed 865 standing buildings.

The Germans holding the city, under the command of Colonel Andreas von Aulock, had a network of tunnels 50 to 60 feet underneath the streets. With such extensive tunneling, the Germans would often emerge and hit the batteries of the 333rd and then disappear again. It became obvious that von Aulock had no intention of surrendering.

Lieutenant Colonel Kelsey had his batteries move forward to within 1,500 yards of the city and kept up the battering for two days. Finally, on August 17, von Aulock, his ears ringing from the constant shelling, came out of his 60-foot-deep hole to surrender directly to Kelsey. Only 182 buildings remained standing.

At that point, all within the 333rd thought that it was time to turn eastward and charge on Berlin, but they were greatly disappointed when they were ordered to turn west toward the port city of Brest. With all the complaints and questions coming at him, Captain William G. McLeod told his gunners that Brest was too important to bypass and, once under new management, it would become a vital Allied seaport. Once that happened, the German Navy would lose its most cherished U-boat facility on the Atlantic.

On August 25, 1944, Middleton’s VIII Corps had all of its three infantry divisions go up against Brest: the 2nd, 8th, and 29th. For this engagement the 333rd was hampered by fog and rain. At times they were literally firing blind, unable to see or adjust their guns. At times they had no idea if they were hitting the 30-foot-high, 15-foot-thick walls of the city, going over those walls, or falling short.

It would not be until September 18, 1944, that Brest was taken from Herman-Bernhard Ramcke and his Germans. During this melee, the 333rd fired 1,500 155mm rounds within a 24-hour period.

Two days after securing Brest, the 333rd was in Lesneven, France, for an extended break and their first USO show. Bing Crosby was leading a whirlwind tour that included blues performers Early Baxter and Buck Harris along with other well-known white actors and actresses. The next day the 333rd returned to the war.

On September 28, the 333rd began a 500-mile road trip, taking them to the final destination for many of them. The VIII Corps, including another black field artillery battalion, the 969th, received orders to head for Belgium. In the first day’s travel, the 333rd covered 165 miles, reaching their “old stomping ground” of Saint Aubin-d’Aubigne, north of Rennes. There they were greeted as heroes. It was such a welcoming event that medic Curtis Adams told his comrades he would love to come back to that region once peace had been restored.

Continuing their northeasterly trek, the 333rd eventually entered Paris. Even though passing through meant only a short stay, all looked forward to seeing the town. Staff Sgt. Thomas J. Forte decided to do some shopping. Having given his bride a cheap tin ring as a wedding band, he needed time to find a reasonably priced, real diamond ring to take home. Shaking his pockets inside out, he realized he could ill afford anything proper. George Davis, Robert Green, William Pritchett, and Mager Bradley dug into their own pockets and generously gave Sergeant Forte enough funds to buy Mrs. Forte a proper wedding ring.

Pushing forward, the 333rd made its last stop in France at Saint Quentin, where the German Army had resided until only a week before. Another 97 miles and they would step onto Belgium soil.

On the last day of September 1944, Lt. Col. Kelsey assembled his battalion for a formal gathering. When in formation the cannoneers noticed hundreds of GIs, black and white, surrounding them. Kelsey informed them, as well their audience, that Sergeant Bill Davidson’s article on the 333rd had just been published in YANK magazine. Kelsey proudly called his battalion together to read it to them.

Apparently Davidson not only witnessed the 333rd’s shooting capabilities upon the church steeple at Pont-L’Abbé on July 1, but had kept tabs on their ongoing activities. He also wrote about the 333rd’s firing its 10,000th round. Then there was that 24-hour period when they fired 1,500 rounds.

Kelsey announced for all to hear that the 333rd was the first African American combat unit to face off with the Germans. And they were still doing it, a feat that had not gone unnoticed by the Germans. It was there and then acknowledged that all the infantry units wanted the 333rd backing them. However proud Lt. Col. Kelsey was at the performance of his soldiers, Captain William G. McLeod was in tears—tears of joy.

In the first week of October 1944, the 333rd split itself between the west and east side of the Our River. The ground the 333rd stood on is called Schnee Eifel (Snow Mountains). The area is heavily forested, with its highest peak being 2,300 feet. This region is also known as the Ardennes. Kelsey’s men were there to support their partners in the 2nd Infantry Division; the two units had forged a well-established, deeply trusting working relationship.

Components of the 2nd moved into some of the 18,000 abandoned bunkers and pillboxes that made up the Siegfried Line or, as the Germans called it, the West Wall––the 1936 brainchild of Adolf Hitler that became the defensive line between his Third Reich and the Western European countries. Its flat-topped concrete pyramid-shaped tank obstacles known as “dragon’s teeth,” guarded by concrete pillboxes, extended for 390 miles.

From Supreme Allied Commander Dwight Eisenhower down the chain of command, the prevailing belief was that this was a line where the Allies could take a winter break, lick their wounds, and be reinforced and resupplied for a resumption of hostilities come spring. In earlier wars it would be called winter camp, since it would be too snowy and cold for any right-minded military man to want to fight a war.

Farther down that chain of command voices spoke out against such an archaic way of thinking. Hushed disagreements flew back and forth. General George Patton knew the history of the Ardennes—Germany had used that same route when attacking France in 1870, then again 45 years later in World War I. That was also the route Nazi Germany had used in its 1940 invasion of France.

Throughout October and November the 333rd would spend a day firing off 150 rounds just to keep themselves busy and show the enemy that the Americans were still around. For many of the men from the Deep South, winter in the Ardennes was the first time they stood in snow up to their knees.

The Battle of the Bulge of December 1944-January 1945 is notorious for what it was; the Allied high command never expected a massive, well-coordinated enemy attack in the middle of December by a battered German Army that was on the run, seemingly on the verge of collapse.

On December 16, 1944, the Germans charged en masse out of the Ardennes just as George Patton expected they would. The American defenders were hit, fell back, andcollapsed. Never before would so many American fighting men be taken prisoner in one battle so quickly. This included the 333rd.

As the inexperienced 106th Infantry Division fell apart, so did the infantry cover for the 333rd that was spread out across the Our River. The 106th lost two regiments, the 422nd and 423rd, to captivity.

On the west side of the Our River was the 333rd’s Headquarters Battery and half its Service Battery. Seeing the rapidity of the attack, Captain McLeod commandeered a jeep and rushed east over the bridge in an effort to bring Batteries A, B, and C and the other half of the Service Battery back across.

No matter which direction any GI ran, he ran into Germans. In these first 48 to 72 hours of fighting, or not fighting, more than 20,000 GIs were marched away as prisoners, including most of the 333rd, but 11 men managed to avoid capture and scurry away through the forest. Among them they had only two rifles and little ammunition. They needed a place to hide, to warm up, and hopefully to eat.

In the little hamlet of Wereth, Belgium, Mathias and Maria Langer and their six children lived in a community that consisted of only nine permanent residences, with Mathias being its mayor. Up until 1919, the region where Wereth sat, known as Eupen-Malmedy, belonged to Germany. In the aftermath of defeat in World War I, Germany was required to give that region to Belgium. For the next 25 years the vast majority within the Eupen-Malmedy region resented that act, clinging to their German history and heritage.

As Hitler’s Nazi regime enlarged its power base, however vile and corrupt, those of Eupen-Malmedy overlooked such transgressions upon humanity. They were Germans before all else. If it was good for Germany, it would be good for them.

The Langer family did not support Germany’s war effort and desire for world domination, and the Langers’ neighbors were aware of their anti-German sentiments. As Nazi aggression expanded, and the fate of Jews became more recognized, the Langers participated in hiding refugees and passing them along to evade persecution and death. They even took in fellow Belgian countrymen escaping German military conscription. With Wereth being such a small community, the Langers’ neighbors were always suspicious of oddities going on within the Langer household and kept close tabs on the family.

After nearly 30 hours of running through the forest, unfed, barely protected from winter weather, the 11 GIs reached Wereth in mid-afternoon, December 17, 1944. They knew nothing of the community. Their immediate needs were to get out of the cold and wet conditions before freezing to death. They needed to dry out, eat, and then somehow get back to friendly lines.

It will never be known how many, or which homes, the 11 viewed while hidden amid the trees. Each one looked warm and inviting. As soon as they decided on the Langer home, they were spotted through a window by Hermann Langer, at the same moment James Aubrey Stewart saw him. That decided their approach. Without anything resembling a white flag of surrender, Curtis Adams unwrapped a field dressing and waved it. This was the first time Langer family had ever seen anyone of African descent.

When the tired soldiers reached the door, Mathias had no reservations about welcoming them. Maria may have been more hesitant since two other guests were hidden in their basement—two fellow countrymen who were evading German conscription. The 11 GIs may not have known that.

Technical Sergeant Stewart spoke up. “Sir, my name’s Sergeant Aubrey Stewart with the U.S. 333rd Field Artillery Battalion. We just escaped from Germans who ambushed us. We’re on our way to American lines to meet our troops. We’re cold, hungry, and exhausted. Would you please help us? We won’t cause any trouble.”

Langer, who may or may not have spoken a little English, invited them in; extra wood was tossed into the stove. Maria put on coffee and passed out bread, butter, and jam. The children offered up their own blankets. Mathias had the 11 remove their boots and socks to dry them out. For just over an hour the Langers hosted their 11 unexpected guests as best they could. Knowing the best escape routes, Mathias told the soldiers that upon leaving his house they should head for Meyerode, 41/2miles to the southwest.

Thomas Forte, George Davis, and Curtis Adams dug into their pockets for what currency they had—mostly French and German coins—to repay the Langers for their hospitality. The Langers refused the offer with Mathias saying they might need that money for their next leg of the journey. Instead, Stewart divided what Chiclets gum he had for the children. Mager Bradley readily gave Maria his unused bar of Woodbury soap that he had received back at Camp Gruber.

Suddenly, a vehicle was heard driving up. Four Germans parked a Volkswagen Type 166 (an amphibious vehicle known as a Schwimmwagen) within yards of the Langers’ front door. An officer of unknown rank got out and pounded on the door, giving indication he knew the 11 soldiers were inside. Since the Americans had been at the Langer house for just over an hour, it became apparent that an unknown pro-German neighbor saw the black soldiers approach and reported that sighting to SS soldiers belonging to Kampfgruppe Hansen of the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler.

It seems Tech. Sgt. Stewart may have led the way in surrrendering to the Germans, as there was no way to escape. The 11 men were removed from the Langer house and held under guard on the road outside as the sun set and the temperature dropped. The SS soldiers questioned the Langers and helped themselves to what was left over from the meal just shared with the Americans. They would eventually leave, never knowing that two Belgian refugees remained hidden in the basement.

The Langers expressed their concern about the welfare of the 11, but the German officer told them not to worry—pretty soon they would not be feeling the coldness. The Langers’ last view of the Americans, at about 7 pm on December 17, 1944, was of them running ahead of the Schwimmwagen into the evening darkness.

Evidence concludes the 11 were run about 900 yards into a cow pasture far from the eyes of those within the hamlet. Shortly thereafter, residents claimed to hear automatic gunfire. Then silence.

It would be well over a month before the bodies of the 11 were discovered. By the beginning of February 1945, the winter snow was melting. Knowing, generally, of the Americans’ fate, residents of Wereth led advancing GIs to where the 11 had lain undisturbed for nearly two months, buried under snow. Some had gone to view the bodies on December 18, but would say and do nothing about it.

The Germans were in, out, and about the area so often that nobody knew who was winning the battle; many felt the SS could easily reappear. When it became obvious that the Germans were gone for good and the American forces would take up a more permanent residency themselves, the Langer children took a patrol from the 395th Regiment to show them the bodies.

Corporal Ewall Seida was the first American to lay eyes on them on February 13. His findings went back to Major James L. Baldwin, regimental S-2 (Intelligence Officer). On February 15, the bodies were laid before medical examiner Captain William Everett. By that time, the evidence of the December 17, 1944, mass murder at Malmedy was well known, but there was a major difference between this murder and the 85 killed at Malmedy.

The bodies at Malmedy showed no evidence of mutilations, nor prolonged torture or suffering from abuse while alive. Most still had personal valuables such as rings with them. It was a murderous act followed by a quick exodus of the perpetrators. For the Wereth 11, there was an abundance of evidence of torture and mutilation—whether alive or following death. Some had one finger cut off, that being the most expedient manner of removing a valuable ring from a dead body when the object refuses to slide off easily.

This does not explain why Sergeant Thomas J. Forte had four fingers literally ripped off one hand. Other corpses had so many broken bones they would not even have been able to crawl. The backs of their skulls were crushed from massive strikes. Teeth were knocked out. Many bodies showed tire tracks—evidence of being run over by a vehicle. One died clutching a field dressing, as if attempting to bind another’s wound. The worst evidence was clear signs of bayonet wounds into their empty eye sockets. Whether alive or already dead at that moment, they were bayoneted in the eyes.

Seven of the victims were buried in the American Cemetery at Henri-Chapelle, Belgium, while the other four were returned to their families for burial in the United States after the war. Batteries A and B of the 333rd made it to the town of Bastogne, where they joined their fellow segregated unit, the 969th, and fought courageously in that historic defense. While supporting the 101st Airborne Division at Bastogne, the 333rd suffered the highest casualty rate of any artillery unit in the VIII Corps with six officers and 222 men killed.

The U.S. Army spent two years investigating the Wereth mass murder, but authorities stated they could find no one responsible for the deaths—no one could be identified as a murderer. No witnesses testified, and there was never enough evidence—no unit insignia, vehicle numbers, etc.—to charge anyone.

In all likelihood those who committed the crime may not have even survived the war. The Army’s answer to settling it all: cover it up, bury it.

Why the difference between Malmedy and Wereth? In dealing with any SS group as diehard, ardent believers in Nazism, race will always be the obvious excuse; the victims did not necessarily have to be of African descent. What may be another underlying cause of the Wereth killings was the history of the 333rd as known by their German enemies. The 333rd had acquired an excellent reputation within the U.S. Army. They became news in YANKmagazine, and Stars and Stripes,too, even if their accomplishments did not hit the mainstream media back home. The Germans would have had access to this story from basic military intelligence-gathering sources.

Well over half of the 333rd were taken prisoner and survived when captured within larger masses of GIs. The Wereth 11 had the misfortune of being caught off on their own and away from witnesses.

However sordid such a crime becomes, another crime followed in 1947. The U.S. Army invested two years investigating the Wereth 11 Massacre. In February 1947, almost two years to the day of the tragedy itself, the Army closed its investigation. Whoever committed the murders was never identified or located. The Langers were not sure of the specific SS unit. At that point the Army officially labeled the findings “Top Secret” and closed the files, hiding them away for decades. In 1949, the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee investigated a dozen recognized war crimes of this nature in Europe. They never knew about the Wereth 11.

Today the crime has yet to be solved. And it may never be.

After the war, the massacre of the Wereth 11 faded into obscurity. But the Langer family, a few historians, and Dr. Norman S. Lichtenfeld, an orthopedic surgeon in Mobile, Alabama, and the son of a 106th Infantry Division veteran, formed a group to raise funds to create a memorial to the 11 victims. Their dreams were realized on May 23, 2004, when a memorial to the “Wereth 11”—the only memorial to black American soldiers of World War II in Europe—was formally dedicated on the Langer property near the location where the massacre took place and where the bodies were found.

Dr. Lichtenfeld, who passed away in 2016, was writing a book about the 333rd and 969th, but it remains unfinished. A TV docudrama, The Wereth Eleven, written and directed by Robert Child, premiered in 2011.

Thank you for this extensive article my Uncle who was in the 33erd field Artillery. I heard from my father he was at the Battle of the Bulge and had been relieved by an officer, then the group was overrun. He was not taken prisoner but was walking around and that officer was taken prisoner. I understand now why he suffered PTSD .

I found this on the back of a picture his mother sent him. Sgt. Frank P Crum

32629820

Batterry C 333rd F.a.vBn

APO 308c/o PM NY

The story of the 333rd was one of the great untold stories of WW2 untill the Wereth 11 movie and the work done by the late Dr Lichtenfeld from Mobile Alabama who also got the new memorial built. As far as I know his book was not finished he worked on for many years. I located seven 333rd vets he interviewed around the time the new Wereth memorial was dedicated. My connection and passion for this story is a family connection. My mothers first husband was Captain Ray Chapple from Illinois. Captain Chapple was Battery B Commander 333rd and he was KIA in Bastogne on Christmas Eve 1944. My mother passed in 1982 and never knew the full story. Most of the stories of the 333rd end with the Wereth 11 massacre. Some of the remnants of Battery B and the other 333 batteries actually made it to Bastogne, after destroying their guns, and before the Germans encircled the small town. They joined up with the other African American 969th batallion which was also part of the 333rd artillery group. The germans got so close to Bastogne the 155s of the 969th were destroying tanks at ranges as close as 200 yards using direct fire. One of my mother letters confirmed German tanks bring destroyed at bastogne /direct fire and so did several 333rd vets saying German tanks had no chance against a 155 high explosive round. Fighting near Wereth / Battery B on the morning of Dec 16 was direct fire too before they were overrun. The 101st was so desperate for 155 artillery rounds gliders were used with pilots risking their lives , some even crash landed in Bastogne, in very bad weather before Dec 24rd . One article called the 155’s, many from the 969th , the linchpin of Bastognes defenses. I think the contribution of the 969th battalion in Bastogne is a great untold story too. My question is could Bastogne have held without the 155s of the 969th manned by African American Soldiers.

I like to thank the family that feed the 11 black soldiers and save the monument site for Wereth 11 massacres site

To our great regret the main action of this memorial doesn’t appear in your story. When Hermann Langer (12 years old) discovered the bodies of the eleven soldiers, he remembered bringing them food and drinks at his parent’s farm on December 17th. He could never forget this vision. In 1994 he decided to erect a monument with the funeral stone of his parents-in-law in order to never forget the massacre of these soldiers fighting for the freedom of his land. Our association was created in 2002 and the dedication took place in 2004. On your picture, Hermann Langer is the third man from the left. Thanks to him the family members learned where and how their son, brother, husband, father….were killed; no longer just KIA! Our website shows pictures of all our events, including speeches from family and students. Just take a look at http://www.wereth.org

Solange Dekeyser

U.S. Memorial Wereth

President

Thank you and Mr. Langer for your efforts to preserve the memory of these American soldiers who were brutally murdered in the service of their country.

My dad’s outfit, 99th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop, 99th Infantry Division, discovered the bodies of the Wereth 11 on February 19, 1945. A notation during the route of march in their unit history states, “February 19, 1945 – Honsfeld, Belgium: Snow was melting uncovering the corpses of the Bulge; 15 GI’s dug up during chow where Jerries had massacred them; Murphy meets his brother from the 106th Infantry Division.”

Honsfeld, where 99th Recon HQ was at the time of the report, was just 4.5km NNE of Wereth.