By Eric Niderost

Southwestern Belgium echoed with the ceaseless tramp of heavy boots on cobbled roads as long brown lines of khaki-clad men marched into Mons and its suburbs. They were British soldiers of the II Corps under Gen. Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien and though the day was warming, all seemed in good spirits. On August 22, 1914, the Great War was only a few weeks old and these soldiers—part of a larger British Expeditionary Force (BEF) of some 87,000 men—were to guard the left flank of the French Fifth Army against the German enemy somewhere up ahead.

Unbeknownst to the British, Generaloberst Alexander von Kluck’s First Army, nothing less than a juggernaut and a key component in the overall German plan, was pouring through Belgium. The First Army was the German right wing, whose mission was to smash through to France in a great wheeling arc to eventually envelop and trap the French Army. Though their intelligence was faulty, the Germans knew that the British army was somewhere ahead—but where, exactly, was a matter of supreme indifference. On August 19, Kaiser Wilhelm II had issued a peremptory order to General von Kluck. It was a typical missive of the Supreme War Lord, full of bombast and posturing, ordering von Kluck to “exterminate the treacherous English and walk over General French’s contemptible little Army.” In actuality, “insignificant” is closer in translation to the original German than “contemptible,” but there was something about the word that appealed to the British Tommies’ wry sense of humor. When they heard of the Kaiser’s orders, the battered but unbowed BEF took the name “Old Contemptibles” as a badge of pride.

The British Expeditionary Force of 1914 was composed of professional soldiers, either active duty personnel or reservists recalled to the colors. The rank and file was drawn from the working classes: tough, hearty, and resilient. Army discipline may have been strict, but military life was no worse, and probably a lot better than the sometimes grim lives they left behind.

As professionals, British soldiers were patriotic, yet didn’t allow love of country to inflame their passions. As they saw it, a soldier’s main task was to fight the enemies of King and Country without knowing why they were fighting. That was something for the politicians to sort out. The regulars didn’t hate Germans, though they didn’t particularly like them—all non-British were “bloody foreigners.” A British officer admitted that, “in the mercenary spirit we would equally readily have fought the French. Our motto was ‘We’ll do it. What is it?’”

But on that morning, the main concern of the BEF was marching to its forward position at Mons. Earlier, in their concentration areas in and around Maubeuge and Le Cateau, the mood had been almost festive. The countryside of northern France was basking in the golden days of late summer, where ripening wheat fields stood in sharp contrast to green pastures filled with browsing cattle. Picturesque farm houses dotted the landscape, and rural villages were thronged with peasants cheering the Tommies on their way.

As the British moved into Belgium, the lush wheat fields and idyllic pasture lands gave way to a barren, urban landscape scarred by the worst of the Industrial Revolution. Mons was a pleasant-enough town, but it stuck out like a jewel in a dung heap. The area was heavily industrialized, a warren of ugly blast furnaces, glass works, and sooty villages. Huge stacks pumped smoke into the hazy atmosphere and slag heaps dotted the face of the suburbs like festering sores.

Even the Belgians called this benighted heart of the coal belt Le Borinage, “the Black Country.” Thick coal dust covered everything, with only a few patches of woods to give a hint of what the countryside had once been like. It was like a vision of hell, the illusion made even stronger by the sweltering August sun.

Overall, the Tommies were in a good mood, though they were tired and many reservists recently called up had sore and blistered feet. Most, however, were eager to come to grips with the enemy. The halt at Mons was going to be a brief one, a “breather” before the advance resumed once again. Even the heat was taken in stride, at least by some. Old hands who had served in India scoffed that the August weather was a “cold spell” compared to Asian climes.

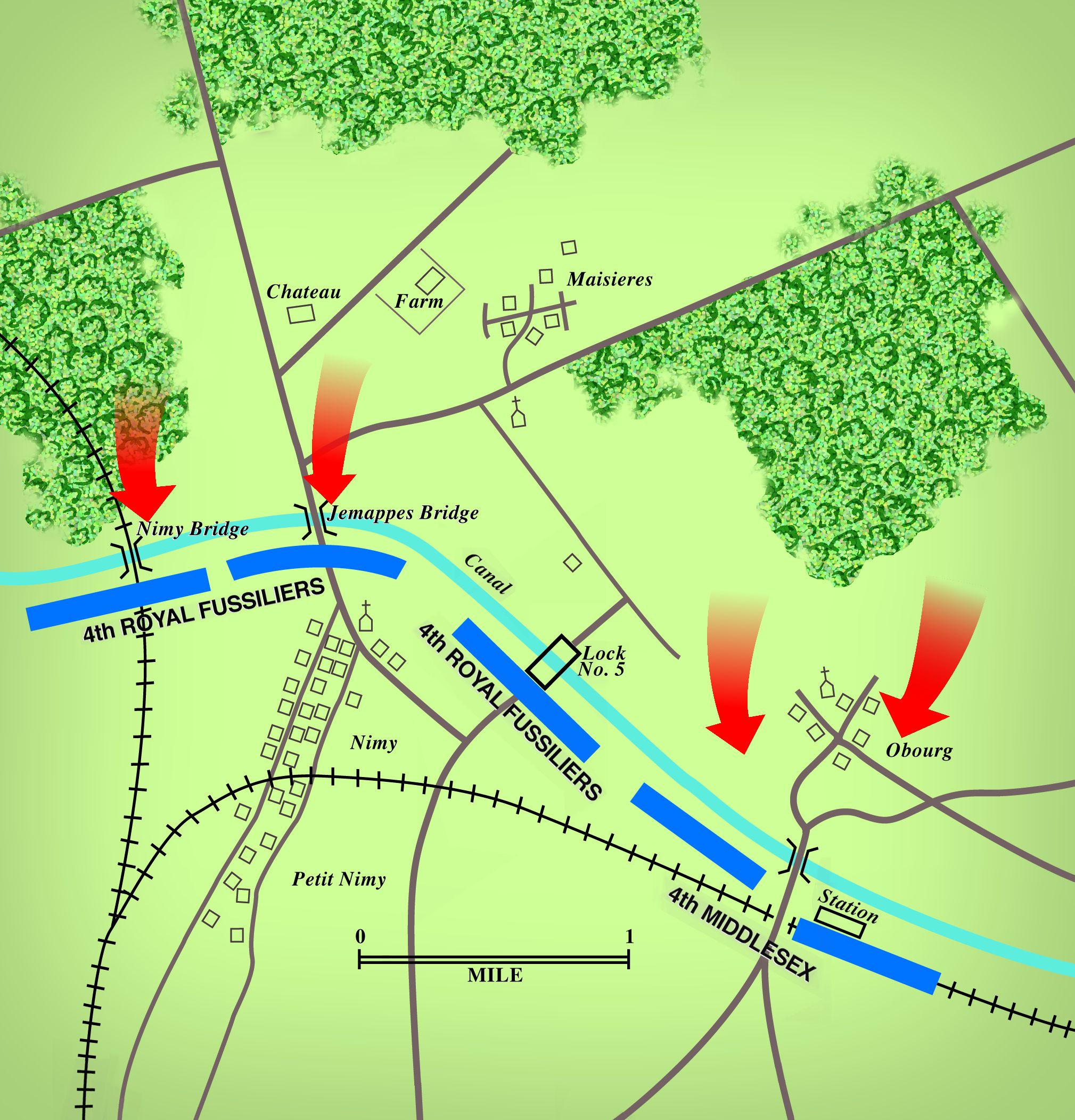

BEF commanders didn’t like the Mons area at all. Cluttered with factories and mines, it was far too urban for decent maneuver. It would be impossible to get a clear field of fire for artillery in the maze of slag heaps, factory smokestacks, and flapping laundry. In the absence of any other suitable point of reference in this urban jungle, the II Corps took up position on the southern bank of the Mons-Conde canal. Never more than 7 feet deep and 64 feet wide, the canal was used by great barges to haul cargo from the Meuse River.

Arrow-straight for most of its length, the 20-mile waterway developed a northeast bulge not long after leaving Mons. This bulge of about 3.5 miles was key to the whole position, and highly vulnerable to attack. Maj. Gen. Sir Charles Fergusson’s 5th Division held the straight portion of the canal, while Maj. Gen. Hubert Hamilton’s 3rd Division was posted along the vital canal “bulge.” To the southeast of the salient, almost at right angles to the II Corps, was Gen. Douglas Haig’s I Corps, though they would play no major role in the coming battle. Beyond the I Corps, almost out of touch, was the French Fifth Army. It was a situation characteristic of Britain’s relations with her French Allies in the early weeks of the war—tenuous at best.

Count Albert Von Schlieffen, Chief of the German General Staff, formulated the plan that bore his name in 1906. The scheme was innovative and risky, but to the Count it was a calculated chance well worth taking. In essence, only 10 German divisions would hold off Russia in the early stages of a war, while 62 divisions would march on France. It was hoped, rightly as it turned out, that the Russian bear would be slow to arouse from hibernation and mobilize for war.

But the key to Schlieffen’s plan was a great enveloping movement that used the Swiss-German-French border region as a kind of pivot for a wheel maneuver. Seven German armies would sweep forward, but the strongest thrust would come from the right wing. This German “revolving door” would rush through Belgium, thrust into northern France and, as the “door” swept west and south, envelop and trap unsuspecting French armies from the flank and rear.

The plan called for the invasion of neutral Belgium, but little thought was given to such political considerations. Any such concerns were probably dismissed because of the overwhelming military advantages a successful maneuver would bring: the war might be won before anyone could protest the violation of Belgian neutrality. The German invasion of Belgium was one of the factors, though not the only factor, that caused Great Britain to declare war against Germany on August 4, 1914.

Time was of the essence; though its army was weak and poorly equipped, Belgium fought bravely and delayed the advancing enemy. Unfortunately, it took the Allied generals—both French and British—several weeks to grasp the significance of the German incursion into Belgium. The French, in particular, considered the German presence in Belgium a mere feint to lure away troops from the main theaters along the Franco-German border.

The BEF was assembled and soon on troopships bound for the French ports of Boulogne, Rouen, and Le Havre. After sorting themselves out, the British Army boarded trains for the region around the fortress of Maubeuge, near the Franco-Belgian border. Because the BEF (87,416 ) was small by continental standards— France had called up more than a million men— French generals overlooked the British as soldiers and tended to dismiss their Allies with a shrug.

The BEF commander was Field Marshal Sir John French, 62, a competent officer who mistrusted his French Allies. Indeed, the first meeting between Sir John and French Fifth Army General Larezac did nothing to assuage the mistrust. The meeting was not auspicious, and even Hely d’Oissel, Larezac’s chief of staff, was sarcastic. When French and his officer arrived at French Army headquarters, d’Oissel snapped, “Well, here you [British] are—it is just about time. If we are beaten it will be thanks to you.” The chief of staff’s remarks set the tone for the conference, which was barely civil.

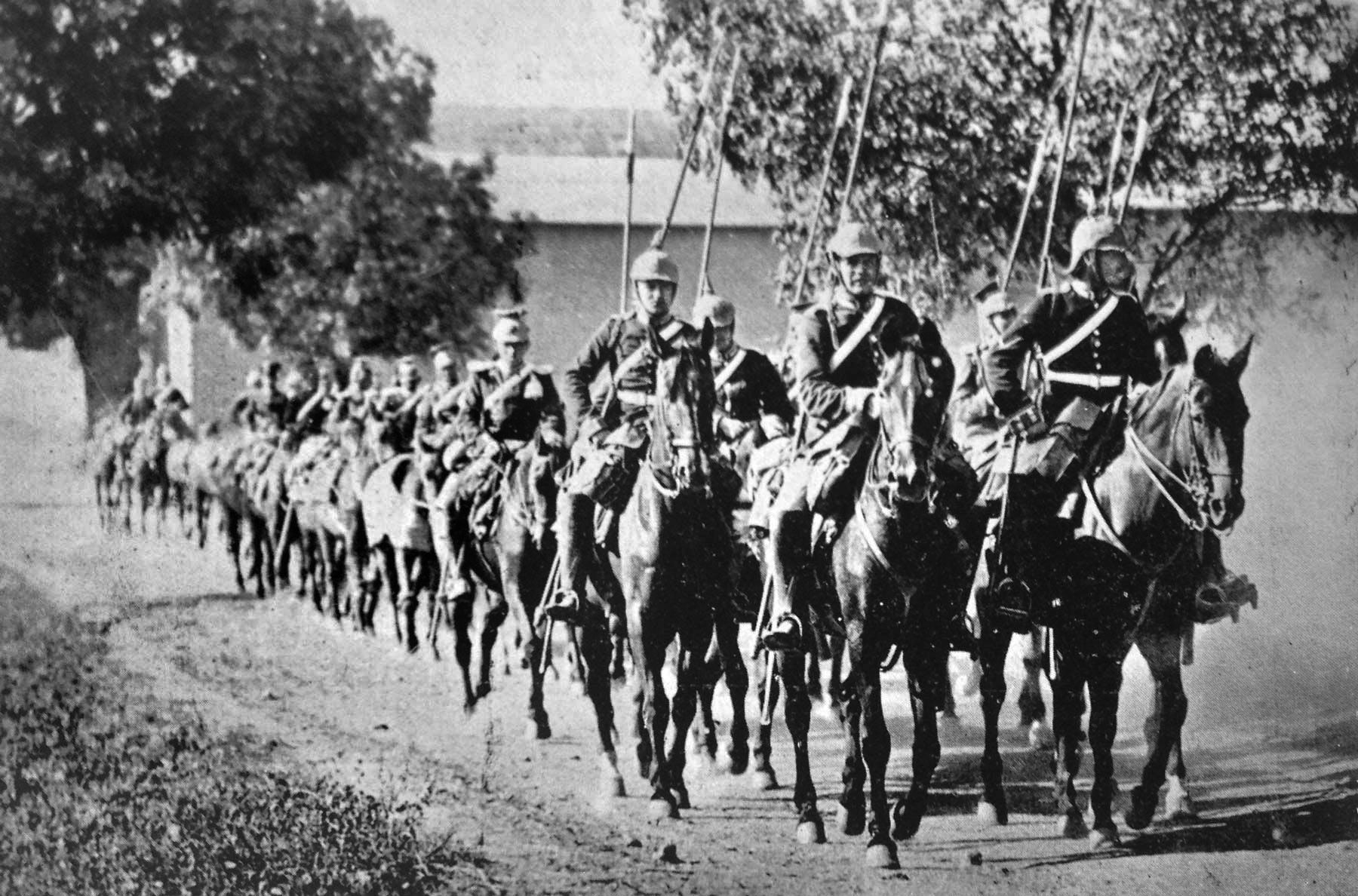

On August 22, as the British moved forward to Mons, reports began to filter in that were straws in the wind—if anyone would heed them. Ironically, the reports came from the oldest and newest methods of war—the horse cavalry and the airplane. From time immemorial, the cavalry had served as the eyes and ears of an army, screening its movements as well as scouting enemy positions. Major Thomas Bridges of “C” Squadron, 4th Dragoon Guards, was on patrol when he encountered some German cavalry. Surprised by the British, the Germans withdrew, and Captain Hornby begged the major for permission to pursue. There was a moment of hesitation as Bridges didn’t know how many Germans were out there. But he could understand Hornby’s excitement and gave permission.

Hornby took two troops of dragoons and pounded down the road at a gallop, the horses’ flailing hoofs striking sparks on the cobblestones. Swords drawn, arms extended in classic cavalry fashion, the British troopers soon caught up with the Germans near the village of Casteau. The British cavalry saber was a thrusting weapon, 35 inches of glistening steel, lethal in the hands of experts. The opposing horsemen were elements of the 4th Cuirassiers, and like all German cavalry, were armed with lances. The Germans soon found they were at a decided disadvantage against sabers, and shortly withdrew.

When more German cavalry appeared, Hornby decided to switch to more modern tactics, calling out, “Fourth Troop! Dismounted action!” The troopers dismounted and took cover behind a chateau wall. Soon, the British cavalrymen poured a steady fire into the gray-clad cavalry, even though the Germans themselves tried to dismount and return fire. Trooper Edward Thomas was one of the first to go into action, killing a German officer at 400 yards. His was the first British bullet fired in anger in the Great War.

Major Bridges broke off the action. German prisoners had been taken and it was not the Major’s task to start a battle. Hornby was triumphant, even ecstatic—he had taken part in a cavalry charge that evoked all the pageantry of medieval romance. Four inches of his sword blade was stained with German blood, proof of his exploits. But beyond the derring-do, some sobering facts emerged. Bridges, a keen observer, came to the conclusion that a very large German force was in front of the BEF. Unfortunately his intelligence, as well as that of other cavalry units, was blithely ignored by headquarters.

Confirmation came from an unexpected quarter—the fledgling Royal Flying Corps. Considered by some to be a mere novelty, the airplane was about to prove its worth. True, planes in 1914 were fragile contraptions of wood, canvas, and wire, but they quite literally gave pilots and observers a bird’s-eye view of the countryside. The Royal Flying Corps was conducting reconnaissance missions, and one flight observed a huge field-gray “snake” that looped and coiled to the horizon. The British airmen were certain the column below was a whole corps, and in fact it was the II Corps of the German First Army.

But the British airmen became disturbed when they discerned the direction the enemy was taking. The German troops were trudging from Brussels to Ninove, then turning southwest toward Gramont. If this line of march continued, it would place them outside the British left flank. The danger was real, and acute. The whole BEF might be encircled. Yet once again, British Headquarters turned a blind eye and a deaf ear to this troubling intelligence.

Lieutenant Edward Spears of the 11th Hussars wasn’t in the front line, but his duties were hazardous in their own way. He was at French Fifth Army Headquarters, serving as the British liaison between General Lanrezac and Field Marshal French. Spears wasn’t a trained diplomat, but he had to get information across without ruffling too many feathers. Because he was only a lieutenant dealing with senior officers, his task was not only unenviable, it seemed impossible at times. He arrived at French’s Headquarters at Le Cateau with a crucial bit of information: The French had been so hard pressed by the Germans that they were falling back, leaving a nine-mile gap between the French Army and the BEF that could widen even more.

French took the news with his customary calm, and ordered that the advance beyond Mons be canceled. But French had his doubts—surely the reports of large numbers of Germans in Belgium must be exaggerated, products of faulty information or excited imagination. For the present, the BEF would hold at Mons. Although the participants had no way of knowing, a major battle, a battle no one had planned, was now in the offing.

The British troops along the canal fully expected to advance the next morning. Summer showers had doused them overnight, making for a somewhat cold and clammy wait for dawn. In the exposed canal salient just west of Mons the 4th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers was facing the Ghlin and Nimy bridges, and on the right was the 4th Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment. The Middlesex companies held an outpost line from the deepest part of the “bulge” to the Bois de l’Haut in the southeast. The whole salient, crucial to the II Corps’ survival, was thus held by eight companies and four machine guns. Just across the canal, the German 18th Division was rapidly approaching with12 Battalions (48 companies), 72 guns, and 24 machine guns.

The Battle of Mons began early on the morning of August 23. After skirmishing with some advance German cavalry patrols, the clash began in earnest with a heavy German artillery bombardment. Shells hammered all up and down the line, but the British held firm. The Tommies had managed to scrape shallow trenches along the canal but most were only a couple of feet deep. Their eyes smarting with smoke, ears deafened by explosions, and noses filled with the stench of cordite, the Royal Fusiliers and the Middlesex Regiment steeled themselves for the infantry assault that was sure to come.

Men in gray emerged from the woods just across the canal, heads covered in spiked pickelhauben. It was the first wave of German infantry coming in close formation. British officers barked commands, and then men opened fire at 500 yards. Private Bradley of the Middlesex Regiment recalled with some astonishment that “they [the Germans] went down like ninepins.” The cacophony of sustained rifle fire filled the air, punctuated by the chatter of machine guns and the explosions of artillery shells. But it was the British rifle fire that seemed to dominate the affair, a hail of lead that swept all before it. Whole files of Germans crumpled to the ground, replaced by others who met a similar fate.

It was at this moment that the British “secret weapon” was revealed. Virtually each soldier was a trained marksman. The norm for British infantry was the “mad minute,” that is, 15 aimed shots per minute into a 2-foot circle at 300 yards. Some soldiers could do 25 rounds a minute, and a few exceptional sharpshooters managed 30. The British Army’s superior marksmanship could be traced to Lieutenant Colonel McMahon, Chief Instructor at the Hythe School of Musketry. Long before the war, McMahon realized that something had to be done to offset superior German numbers in the event of war. He recommended an increase of machine guns to six per battalion instead of the standard two. When turned down by the powers that be, McMahon focused on improving infantry marksmanship. The result of such foresight was Mons.

Some of the leading German units were cut to pieces, scythed down like gray stalks of wheat by British bullets. But the British were taking casualties too as German shell bursts ripped into shallow trenches, shrapnel wounding and maiming those not killed outright. But there was no question the Germans were getting the worst of the exchange. In fact they thought, and continued to think long after the battle, that the Mons-Conde canal was bristling with British machine guns. Yet in reality British machine guns were few. As mentioned, the whole length of the vital canal salient was protected by only four machine guns—and two of them were stationed at the Nimy Railroad bridge.

Captain Thomas Wright of the Royal Engineers had been detailed to oversee the destruction of eight of the canal bridges, but he and his men were having no end of difficulties. Some bridges were demolished, but others were not due to heavy German fire, faulty equipment, or even lack of equipment. Wright found to his dismay there was a lack of exploders to ignite the charges. At the Mariette Bridge, the Captain swung hand over hand under intense enemy fire in order to ignite the charges, but without success. Wounded in the head, Wright and his RE sappers were forced to fall back, covered by the accurate musketry of the 1st battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers.

Wright had better luck at the Jemappes Bridge, which was ably defended by the 1st battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers. Distinguished by their jaunty Glengarry caps, the Scotsmen poured a heavy and accurate fire into the Germans as they vainly attempted to cross the span. Lance Corporal Charles Jarvis and Sapper Neary had been assigned the Jemappes Bridge, but found they lacked the proper equipment for demolition. Charges were strategically placed on the bridge, but they were without exploders and leads.

Sapper Neary was sent to fetch the exploders, but he failed to return. Lance Corporal Jarvis somehow got a bicycle and went in search of the materials himself. In the course of his pedaling he came across the wounded Captain Wright, who told him to get back to the bridge. Wright himself would bring back the exploder in a car. The Captain was as good as his word, and after an hour and a half of hard work Jarvis managed to blow the bridge. Jarvis was assisted by a Private Heron of the Royal Scots Fusiliers, the two men laboring under heavy German fire from three sides.

German pressure was mounting, and it was clear the British could not hold indefinitely. The Tommies continued to blaze away with their short magazine Lee-Enfield rifles, cutting down incredible numbers of Germans, but sheer numbers were beginning to tell. The vulnerable salient held by the Royal Fusiliers and Middlesex was coming under particularly heavy pressure. In the afternoon the forward companies of the Royal Fusiliers were ordered to withdraw, but they had 250 yards to cross before reaching the comparative safety of the covering companies.

The two machine guns at Nery Bridge had had a rough time of it, with crew after crew killed and wounded by German fire. But when one machine gunner was killed, another came forward to take his place. Lieutenant Steele decided that if the Fusiliers had to withdraw, their best chance was to have covering machine-gun fire. Lt. Maurice Dease was in charge of the machine gun section, but after being hit several times he finally succumbed to a mortal wound.

Steele now came up and asked—not ordered—Private Sidney Godley to remain behind and man the machine gun. Godley agreed, removing the corpses of three previous gunners before he could take his position. The Fusiliers withdrew, covered by his machine-gun fire. According to one account Steele flung the now-unconscious Dease over his shoulders and took him away, staggering under the latter’s dead weight. It was a miracle that Steele reached safety with his burden, since German fire buzzed through the air and peppered the ground all around them.

Private Godley manned his post for more than two hours, his Vickers-Maxim machine gun spitting out a stream of bullets at five hundred rounds a minute. He managed to prevent the Germans from crossing the railroad bridge, but wasn’t going to emerge unscathed. A German shell exploded nearby, sending a piece of shrapnel lancing into Godley’s back. Later, a German bullet slammed into his skull, but he kept up his rate of fire. Exhausted, sweat-drenched, blood pouring from wounds, Godley could no longer delay the inevitable. In a final act of defiance, the Royal Fusilier broke his machine gun up and flung the pieces into the canal.

Godley’s heroic one-man stand had given his comrades a precious two hours to retreat. Captured, Sidney Godley spent the remainder of the war in a German prison camp. For his heroism he was awarded the coveted Victoria Cross.

There were small rear-guard actions with the Germans, and usually the British gave their pursuers the slip after inflicting heavy casualties. Young trumpeter Jimmy Naylor of the Royal Field Artillery, just 16, witnessed an infantry action that made an indelible impression on him. It was as if it were a peace-time drill, or a competition for a marksmanship badge. The officers called out the ranges, and as the Germans drew closer the numbers went ominously downward. “He [the officer] was saying,” Naylor recalled, “‘At four hundred … At three-fifty … At three hundred … Rifles blazed, but the Germans came on … And the officer, still cool as anything, [said] ‘At two-fifty, At two hundred.’”

The Germans wilted under a punishing fire, only to surge yet again as fresh units came forward into the British meat grinder. Then, as Naylor continued to watch, the British officer “said ‘ten rounds rapid!’ And the chaps opened up—and the Germans fell down like logs.” The Germans were driven off, albeit temporarily, and the withdrawal continued.

The German Army was in some ways the best army in Europe, but its ranks were largely filled with conscripts. Such marksmanship as the British displayed was beyond their experience. Hauptmann (Captain) Von Brandis of the 24th Brandenburg Regiment said, “Our battalion alone lost three company commanders … besides every second officer and every third man.” Another German unit, the 75th Regiment, lost 5 officers and 376 men.

The Battle of Mons and its immediate aftermath was over, even though the campaign had barely begun. It was a truly amazing achievement: General Smith-Dorrien’s II Corps of only two divisions had held off no less than four, and eventually six, German divisions. Yet for Sir John French, commander-in-chief of the BEF, the situation was grave, since it was his responsibility to save Britain’s field army. Not far away was the French fortress town of Maubeuge, with solid ramparts built by the 17th-century French engineer Vauban. It was well fortified and provisioned, and might provide the battered BEF a welcome refuge. French later admitted he was sorely tempted to retreat to Maubeuge, but the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 provided a cautionary tale for the wary British general. In 1870, an entire French Army had been bottled up in Metz and eventually forced to surrender.

French decided to ignore the siren call of Maubeuge and ordered a continued withdrawal. British Army morale was high, and they were masters of the “leapfrogging” withdrawal. Units fell back, dug in, and held up the enemy while other units passed through them. Then, the covering units withdrew and the process was begun all over again.

On August 25 the 4th (Guards) Division found itself at Landrecies, a quiet town of no real consequence. The 4th (Guards) brigade were part of the King’s Household troops, those red-coated, bearskin-hatted sentries that patrol the monarch’s palaces and whose colorful Changing of the Guard ceremonies were and are popular attractions. But the Guards were tough, seasoned soldiers, not merely ceremonial troops. The Coldstream Guards, for example, could lay claim to being the oldest regiment in the British army, with origins that could be traced back to 1650.

On the evening of August 25, The Guards brigade gratefully relaxed in the billets they found at Landrecies. The town was guarded by machine-gun picquets posts manned by the Coldstream Guards, and though the night was pitch black the soldiers had no reason to feel nervous. It was thought that the Germans were many miles away. But then the rousing strains of the French anthem La Marseillaise floated on the wind; a body of lustily singing troops were coming up the road. The forward Coldstream picquet shouted out a challenge, and a reassuring “Francais!” came out of the darkness in reply.

Before the Coldstreamers could react, German soldiers emerged out of the night like ghostly phantoms. The French speaking had been a ruse, hastily contrived, as the Germans had not expected to find British troops in Landrecies, and were initially just as surprised as the Tommies. The men rushing forward were the vanguard of the German 27th Regiment and although the forward picquet was overwhelmed, the defenders of the main British picquet 20 yards behind had been more suspicious.

Fighting soon broke out and Landrecies became bedlam, with Coldstreamers and other Guards units rushing into action or hastily fortifying the little town. The confusion was made worse by the presence of the I Corps Headquarters. Rear echelon staff officers aren’t used to front-line dangers, and some added to the overall turmoil. A few even panicked; one full colonel was seen excitedly emptying his revolver down a street, his targets some innocuous horses tethered there.

I Corps commander Sir Douglas Haig didn’t panic, but he did feel they might be surrounded and cut off from the main body of the BEF. “If we are caught, by God,” a grim-faced Haig exclaimed, “we’ll sell our lives dearly.” The crisis was more apparent than real; the Guards were seasoned professionals, and soon sent the Germans packing. The I Corps then shortly resumed its withdrawal without further molestation.

The seeming crisis at Landrecies diverted attention from the very real peril the bloodied II Corps was facing. Its commander, Gen. Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, was known as an excellent officer who genuinely cared for the welfare of his men. He had been in the army for more than 30 years and as a young subaltern, he had survived the dreaded assegai spears of Isandlwana during the Zulu War of 1879. Smith-Dorrien knew that constant marching and fighting, coupled with lack of sleep and the enervating heat, was taking a heavy toll. But if he could stand and fight, at least long enough to give the Germans a bloody nose, they might back off. At the very least, it would win some precious time.

And so it was that Smith-Dorrien resolved to fight at Le Cateau, about 25 miles southwest of Mons. The British right flank was allotted to the 5th Division, which was anchored at a point near Le Cateau. The 3rd Division was in the center, with two brigades on high ground near the villages of Inchy and Caudry. The Germans soon appeared, and heavy fighting ranged for six grueling hours. The British right flank was subjected to particularly heavy attacks.

The battle began on August 26, the anniversary of the great English victory over the French at Crecy in 1346. Perhaps the date would be a good omen for the British II Corps. The Germans began shelling British positions at 6 a.m. More and more German batteries unlimbered and went into action, and by 10 a.m. the 5th Division was being subjected to enfilade fire. The 2nd Battalion, the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (KOYLI) was hard hit, as were the Royal Field Artillery batteries that were returning German fire.

Much of the battle became a repetition of Mons. After it was judged that the British were sufficiently softened up by their artillery, German infantry was moved forward in close formation. Once again, superior British marksmanship shredded German ranks, and once again sheer superiority of numbers began to tell. Smith-Dorrien ordered the 5th Division to retire. Above all, the precious artillery was taken to safety, the cry of “save the guns!” being an army maxim since the days of Marlborough and Wellington. A few British units were overrun, but the majority managed to slip away safely.

Yet again, the Germans were shaken by the heavy losses sustained at Le Cateau. Smith-Dorrien’s gamble had paid off, and never again was the II Corps so hotly pursued. As he had hoped, Smith-Dorrien dealt the enemy “a smashing blow,” as he reported in his autobiography, and then was able to “slip away before he could recover.”

German blunders, miscalculations, and sheer wishful thinking undermined their plans. After Mons, von Kluck persisted in believing the “defeated” British would scurry away to the channel ports and home. At one point von Kluck sent his II Cavalry Corps to head them off, and then moved forward four infantry corps to drive them to Maubeuge—an option the British had already decided to bypass.

The British slipped the net, but von Kluck still clung to his illusions. German problems were compounded by the decisions made by the Chief of the German General Staff, Generaloberst Helmuth von Moltke. From his Supreme Headquarters at Coblenz, things seemed to be going very well for the Germans in France. Indeed, it seemed to von Moltke that “the great decisive battle in the West had been fought and decided in Germany’s favor.”

Nothing could have been further from the truth. The French had experienced setbacks, but were not decisively defeated, and the BEF was far from the broken reed of von Kluck’s fevered imagination. Nevertheless, von Moltke was so convinced the Germans had won in France that he committed a fatal error by transferring two corps from the German right wing to the hard-pressed Eastern Front.

In the meantime, the BEF had managed to evade its pursuers, though the soldiers were exhausted almost beyond human endurance. Many were hobbling painfully on badly blistered feet; boots cut into sores, but soldiers didn’t dare remove them for fear they would never be able to put them on again. Most of the troops hadn’t had a decent night’s rest in many days, and could barely keep their red-rimmed eyes open. They were ragged, unshaven, and filthy. The merciless sun still seared man and beast alike, producing a tormenting thirst.

Yet conditions improved, slowly, at least for some. Troops were able to snatch some sleep, and a few were even close enough to water to wash, shave, and drink their fill. Rations were also coming in, so hunger was put at bay. Most of all, the British soldiers still had high morale, and their sardonic sense of humor was still intact. They were delighted when they discovered the opposing German general’s name was von Kluck. It had great possibilities for a marching song, because it rhymed with their favorite Anglo-Saxon obscenity. Spirits lifted and marching was made easier when the troops cheerfully bellowed, “Oh, we don’t give a f—k for old von Kluck, And all his f—king great army!”

On September 1, French Commander-in-Chief Gen. Joseph Joffre huddled in conference with Field Marshal French. Joffre was receiving reports that von Kluck’s First Army was marching sharply southwest. Instead of sweeping west of Paris then swinging east, von Kluck was actually marching far east of the French capital. As he marched southeast, von Kluck was unwittingly exposing his flank to a new French army assembling under Gen. Joseph Maundury. The Germans were apparently unaware of this new Sixth Army that was gathering to the north of Paris. All the British needed to do was to cooperate with their French Allies and draw the Germans on. Once von Kluck reached the Marne River, the trap would be sprung.

On that same day, a cavalry and artillery action took place that, though small in scale, was to have a decisive impact on the future course of the campaign. General von Kluck was indeed moving southeast, his objective to “settle with the debris of the Franco-British army.” The German general seemed almost obsessed with destroying the BEF, or at least its “remnants.” It must have been infuriating and puzzling to von Kluck. The British lion’s fangs had been drawn, yet in battle after battle it still possessed a considerable bite. It didn’t make sense. And yet von Kluck clung stubbornly to his illusions, insisting he was mopping up shattered and defeated remnants.

On August 31, General C.J. Briggs’ First Cavalry Brigade halted at Néry, a small village some 50 miles northeast of Paris. The First Brigade, part of General Edmund Allenby’s Cavalry Division, was screening the western, or right, flank of the BEF. The command consisted of the 2nd Dragoon Guards (The Queen’s Bay’s), the 5th Dragoon Guards, and the 11th Hussars. Each of these regiments was distinguished in its own right; the 11th Hussars, for example, had been commanded by Lord Cardigan of Crimean War fame, and had taken part in the Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaklava.

Altogether, there were nine squadrons of cavalry. The First Cavalry Brigade was accompanied by “L” Battery, Royal Horse Artillery. It made sense to stop at Néry; the Germans were far away, and here was a chance at last to snatch a bit of rest after a fatiguing few weeks. Horses were picketed for the night, and cavalrymen cocooned themselves in their cloaks around blazing campfires. Although the heat lingered in during the day, the nights were becoming chilly—a sure sign of the approach of autumn. The soldiers had to get some sleep, because the brigade was due to move out again at 4:30 a.m. But fog enveloped the area like a blanket, so the departure was postponed for an hour.

It was a chance for some extra rest, and an opportunity for Battery “L” to water its horses at a small pond near a sugar factory. After watering and feeding, the teams were hitched to the guns and limbers in preparation for moving out. Colonel Pitman of the 11th Hussars was a sensible man, and though the Germans were probably far away, he decided to send out a patrol to scout the high ground west of Néry.

The 11th Hussars rode on through the clammy mist, then were brought up short by the sight of gray horsemen in spiked-topped pickelhauben. They were Germans of von Garnier’s 4th Cavalry Division, whose main mission was to screen von Kluck’s exposed right flank. At the command “Files About! Gallop!,” the British troopers rode hell for leather to warn their comrades at Néry. Almost simultaneously, German scouts had reported to von Garnier that they had seen British cavalry and artillery bivouacked nearby. The Tommies still had their mounts picketed, and their guns were limbered for transport, not a fight. They would be easy prey, an opportunity too good to miss. Von Garnier had 24 squadrons and a full battery of artillery.

In the meantime, the 11th Hussar patrol galloped in to report what they had seen. Caught by surprise at this sudden turn of events, troopers and gunners scrambled to prepare for the attack they knew must come. Major Sclater-Booth, commander of “L” Battery, shouted to young trumpeter Harry Gould to sound the alarm. Just as Gould raised the instrument to his lips, the first German shell came crashing down, knocking the Major unconscious and throwing the trumpeter to the ground. Shaken, Gould got up and blew the alarm as ordered, the clarion notes sounding above the rising chorus of artillery bursts.

Nery was transformed from a peaceful haven to an incarnation of hell. Some cavalry horses stampeded in terror as men grabbed weapons or tried to saddle rearing mounts. The German cavalry was accompanied by three 4-gun horse artillery batteries, and they soon found “L” Battery’s range. It was a scene that almost defied description, with flaming shell bursts flaying, ripping, and disemboweling men and horses with horrifying ease. Horses whinnied with fear, plunging and rearing, but constrained because they were hitched to limber poles that were on the ground.

Within minutes, the battery was a bloody shambles, a torn landscape of smashed limbers, overturned guns, and eviscerated horses. Gunners who tried to get their artillery into action were cut down before one shell was loaded. But Battery Capt. E.K. Bradbury appeared, shouting, “Come on! Who’s for the guns?” His example seemed to galvanize the others. Bradbury and his companions managed to get three 13-pounder guns into action, but one gun took a direct hit that disabled it, and a second gun’s fire ended when all its crew was dead or wounded.

Only No.6 gun fought on, one solitary British 13-pounder against a whole German battery. Bradbury was assisted by Lieutenant Campbell, Sergeant Nelson, Gunner Darbyshire, and Driver Osborne. Later, Battery Sgt. G.T. Dorrell lent a hand. Bullets zipped through the air like angry wasps; more than 20 yards of open ground had to be covered to get to the ammunition limbers. More and more German guns stopped firing at Néry and concentrated their fire on the lone British field piece. At one point 12 German guns were blazing away at No. 6, creating a storm of fiery explosions, smoke, and cascading shrapnel. German shell bursts mushroomed with gouts of flame and acrid clouds of greenish cordite smoke, killing and wounding with every passing minute.

It was an incredible experience, something indelibly etched in the minds of the survivors. Darbyshire later recalled: “These 13-pounder guns can be fired at the rate of fifteen rounds a minute…. The concussion of our own explosions and the bursting German shells was so awful I couldn’t bear it for long … my nose and ear was bleeding because of the concussion.” The gunner needed a break, so he switched to carrying shells from the limber. His place was taken by Campbell, but moments later a German shell exploded under the gun shield that tossed the lieutenant like a rag doll, throwing him six feet. Mortally wounded, he lived only a few minutes.

Against heavy odds gun No. 6 and its valiant crew managed to silence three German guns. But finally, No. 6’s ammunition ran out. By that time most of the crew were dead or wounded. Bradbury was lying to the side, his legs blown off by a German shell.

While the remnants of Battery “L” had fought so desperately, the cavalry troopers had maintained a brisk fire against opposing German horsemen and infantry. Just when the issue seemed most in doubt, reinforcements arrived in the form of the British 4th Cavalry Brigade, Battery “I” of the Royal Horse Artillery, and some infantry. Suddenly the tables were turned, and apparently the German commander ordered a retreat. But the German horse soldiers panicked and a retreat quickly became a rout. Reeling from the new British pressure, the gray soldiers pressed the flanks of their mounts and galloped away in headlong flight.

published in the Illustrated London News in 1914.

German artillerymen seem to have panicked as well, their fear heightened by Battery “I”’s well-aimed bursts. Lt. Willoughby Norris, C Squadron, 11th Hussars led his men toward the Germans, the troopers entering the battery with a cheer. Germans who could not flee surrendered; Norris bagged some 78 prisoners.

The action at Néry was small in scale, but large in its repercussions. British casualties amounted to 135 officers and men, of whom 49 were from Battery “L.” Victoria Crosses were awarded to Sergeant Nelson, Battery-Sergeant Dorrell, and Captain Bradbury, the latter awarded posthumously. The German 4th Cavalry Division had ceased to exist as a fighting force. Eight guns had been taken by the 11th Hussars, and four more were found abandoned in the woods. In effect Von Garnier’s command had been neutralized. Shaken and demoralized, the survivors of the 4th Cavalry Division did not reassemble until September 4, and even then they were not considered fit for active duty.

In the meantime, von Kluck was wheeling east, doggedly determined to destroy the “remnants” of the BEF and French Army. Reports of French troops to the west he dismissed as second-line Territorials. The Germans, too, were getting ragged and exhausted, but the dream of impending victory sustained them. It was soon to prove a nightmare.

On September 7, General Maunoury’s 6th Army, still largely undetected by the Germans, struck hard at von Kluck’s right flank. This action was the first of several clashes collectively known as the Battle of the Marne. Surprised, von Kluck turned westward to face Maunoury’s threat—and in so doing, opened a gap between his own First Army and von Bulow’s Second Army. A resurgent BEF plunged into the gap between the two armies.

French and British forces hit hard at the Marne, successfully turning the German flanks. Both the German First and Second armies managed to extricate themselves and retire behind the Aisne River. A “race to the sea” eventually established the infamous trench lines of the Western Front. It would be the beginning of a bloody stalemate destined to last for four years.

The Marne had proved a decisive turning point, depriving the Germans of their best chance for victory in World War I. It was here that the seemingly insignificant—at least in terms of scale—action at Néry was brought into sharp relief. If von Garnier’s German 4th Cavalry Division had not been neutralized and scattered on September 1, it is more than probable they would have discovered the newly forming French 6th Army assembling on von Kluck’s flank and alerted the general of its presence. The Battle of the Marne might have turned out differently.

The French Army numbered well over 1,000,000 men, and by most estimates the BEF less than 100,000. The British army made several contributions during those crucial opening weeks of the war. For one thing, they blunted von Kluck’s advance, even if they did not stop him, and inflicted far greater numbers of casualties on the Germans than their numbers would suggest. The sheer professionalism of the “ Old Contemptibles,” their toughness and “mad minute” marksmanship, more than made up for the mistakes of their commanders.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments