By Brooke C. Stoddard

May 10, 1940, marked the beginning of the war in western Europe. Nazi-controlled Germany invaded Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg, and France. For several days, it appeared to Allied commanders that the assault was a revised version of the attack of August 1914. They could see, of course, that there were new elements—the use of paratroopers and gliders to overwhelm strongpoints, and of Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers as close air support to disrupt marshaling and supply areas behind the front lines—but they believed the main thrust toward France was coursing through Belgium, as it had in 1914.

Calmly, the Allied commanders believed they had a plan to deal with the massive invasion. They thought they had the situation under control. Within days, they could see that they did not have the situation under control at all. Their plan was ruined as disarray and chaos spread like floodwaters from a swelling river. This climate of confusion bred hasty decisions on both sides that would have long-lasting effects.

A Freak Accident Changes the Course of the War

Most major decisions affecting May 10-28, 1940—that is, up to the time of the mass evacuations from Dunkirk—were necessarily made months earlier. They were made by the high military commands of both sides based on their objectives and the perceived intentions of the other. By a cruel twist of fate, however, the most major decision that had been made before the shooting started was the result of a freak accident, which changed the German attack plan to one that proved astonishingly successful.

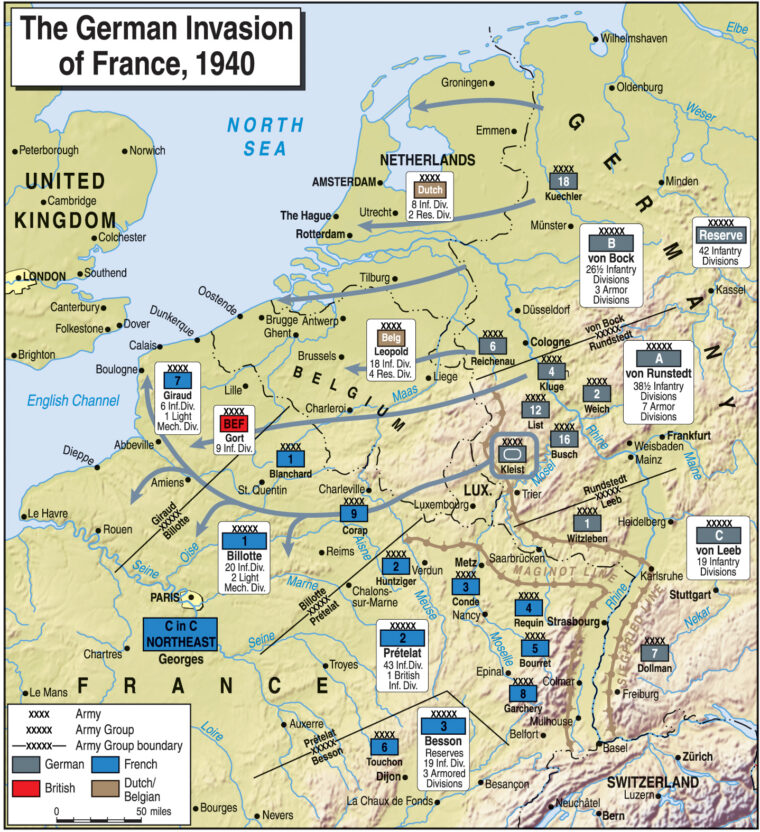

Through the fall of 1939, the Wehrmacht was to follow a modified Schlieffen Plan, pressing its strength through the Low Countries in a wide right-flank sweep touching the English Channel. The Germans would push back the Allied armies and then continue on to Paris, ostensibly knocking France out of the war and bringing Britain to terms.

On January 10, however, a German military plane carrying two officers lost its way in the clouds near the German-Belgian border. It sought refuge on the ground and, although believing it was landing in Germany, actually set down in Belgium. Belgian soldiers rushed to the plane. One of the German officers, bearing the Wehrmacht plans for the main thrust through the Low Countries, immediately tried to burn the documents. The Belgians seized them, and the German attack plan was in Allied hands.

Von Manstein’s Bold New Plan

Hitler was furious. He meant to launch the offensive on January 17 and now realized he would have to delay. Into these anxious days stepped Lt. Gen. Erich von Manstein, who promoted a scheme that called for the drive through the heart of the Low Countries to be a massive one, but nonetheless a diversion. By his lights, the best fighting troops, the swiftest and the strongest—the panzer divisions—would be sent south, to just north of the end of the Maginot Line, for an attack through the Ardennes region in southern Belgium and Luxembourg.

The idea was to make the French, British, and Belgians believe that the main attack would come through central Belgium and send their best troops there. Meanwhile, the panzers would break through the weak defenses on the French side of the Ardennes and burst into the rear of the Allied armies fending off German forces farther north.

At worst, the panzers would wreak havoc among the secondary troops of the Allies. At best they would drive to the Channel to cut off the northern armies from both their line of supply and their fellow armies to the south. Their backs to the Channel, pressed from east, south, and west, the Allied northern armies might be compelled to surrender. A million fighting men in prisoner of war camps would be a powerful bargaining chip in any discussion of terms dictated by the Germans.

The new Wehrmacht plan was risky. In the Ardennes, the panzers would have narrow roads to travel and poor bridges to cross. They would be lined up end to end for miles, vulnerable to concerted air attack. They would still have to breach the strong French defenses at the Meuse River, but if they could overwhelm the Meuse defenses there would be little to stop their drive all the way to either Paris or the Channel. Still, their thrust across northern France would necessarily be narrow and thus vulnerable to attacks that could potentially sever their lines of supply.

Nevertheless, Hitler had proved he was a gambler, and a lucky one. He approved the plan and set it in motion on May 10.

The Allies’ Plans Play into Hitler’s Hands

The pre-attack decisions of the Allies played precisely into his hands. The Allied leaders had always believed the main German effort would come through Holland and central Belgium. They had thus decided to place their best fighting troops opposite the expected thrust through central Belgium. The remaining troops would be formed along the Ardennes where little trouble was expected, and static troops could man the Maginot Line along the border with Germany itself where they could repulse any German drive in that area.

Thus the big decisions and dispositions were made, but the French and British could not station themselves on Belgian territory. The Belgians did not want to provoke the Germans, so they held the French and British at arm’s length. They made only cursory coordination of defense efforts with the French and British, who were compelled to remain on the French side of the border. The Allied plan necessarily had to be to wait until Germany violated Belgian neutrality, then advance into that country and stop the Germans just as they had in 1914-1918. Such an advance and engagement with the German thrust into central Belgium would, of course, be exactly what the Wehrmacht wanted. The Allied armies would be further removed and less likely to interfere with panzers clanking into their rear to the southeast.

The German plan worked to perfection. Once Wehrmacht Army Group B advanced into Holland and Belgium on May 10, the 35-division Allied Army Group One under French General Gaston Billotte, which included the nine divisions of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), wheeled into Belgium. From the start, things went badly for the Allies. The Germans were much swifter in the Low Countries than they had expected. Luftwaffe bombers created havoc at marshaling and supply points. Fleeing refugees clogged the roads on which the Allied armies needed to advance. The defensive positions the Belgians had been building along canals and rivers were not nearly as strong as the French and British had hoped they would be. Communication among French, British, and Belgian commands was poor. Still, the Allied command believed the attack was unfolding as they had foreseen. Major decisions on the fly were not needed.

Allies Thrown into Chaos by the German Breakthrough

That is, until the Germans broke out of the Ardennes and overpowered the defenses along the Meuse. With that river barrier broken, the Allied plan for the defense of Belgium and northern France was suddenly obsolete and many days of confusion and chaos were at hand. The next two weeks were pregnant with fateful decisions, all made in the fog of confusion and poor military intelligence.

The reaction among the French commanders to the breakthrough at Sedan was mainly one of disbelief and paralysis. The overall Allied commander, General Maurice Gamelin, operating from his Vincennes (a Paris suburb) headquarters, was not using radio for communications, but rather an unreliable civilian telephone system and motorcycle riders. The riders had great difficulties on the clogged roads and were sometimes injured or killed in accidents. Word did not get to BEF commander John Standish Vereker Lord Gort of the important German thrust at Sedan until May 14, or that they had broken into the rear area of Army Group One until May 16.

The French Ninth Army, which was positioned to halt any drive through the Ardennes, was by then coming apart. The Ninth’s soldiers were not well trained and, once confusion became infectious, they could not stand up to the German power relentlessly driving at them. This was due partly to the fact that the front was shifting so fast that commanding officers did not know where it was. Junior officers received orders that were obviously long out of date. Moreover, many junior officers became separated from their men. Hundreds of soldiers fled for home; whole companies and battalions ceased to exist. The Ninth’s commanding officer, General André Corap, was sacked on the 15th.

Some soldiers of the Ninth did what they could, but coordination was beyond them. The panzers of General Heinz Guderian’s XIX Armored Corps clattered on, ferociously intent on driving all the way to the sea. Gamelin had to confess to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill on the 16th that there was no reserve to stop them, or, to be more exact, what reserves were available were scattered and could not be effectively concentrated to staunch the flow of Germans out of Sedan.

This same day, the 16th, Gort learned that the First French Army, which was on his right, was preparing to pull back. He was furious. No one had told him his flank would be exposed. Finally, Billotte issued orders for a coordinated retreat over the next two days to the River Escaut, there to make a stand. By this time Gort was losing faith in his French commanders and comrades in arms. Lack of communication, lack of coordination, confusion, and even chaos were overtaking the Allied command structure. The fog of war descended with a vengeance.

In particular, Gamelin seemed unable to take any decisive action. He was allowing Alphonse Georges, in command of northeastern France, to control the battles, but Georges was ineffective as well. Only one concerted French counterstroke was launched. This was made by Colonel Charles de Gaulle, who commanded an armored counterattack at Montcornet west of Sedan on the 17th. It made an impact, but lacked the strength to hold up Guderian for long.

Gamelin Tries a Counterstroke

Finally, Gamelin could see his way to a counterstroke. He wanted Georges and Billotte with the northern armies, including the BEF, to divert themselves from the Germans in central Belgium long enough to attack south in France behind the westward-driving panzers. Gamelin would try to muster some strength south of the panzers to attack north, meeting up with Billotte and thus cutting off the Wehrmacht armor from supplies and infantry following behind to consolidate the panzer’s gains.

Such a two-fronted attack would have been difficult under any circumstances. Both north and south of the panzer thrust, the Allied soldiers had been fighting or on the move for days. In addition, communication was bad enough on one side of the German penetration, but leaping it for a coordinated attack from both north and south toward the same objective and at the same time would be a tremendous undertaking.

In any event, Billotte was losing heart. On the 18th, when the retreating northern armies were meant to make a stand along the River Escaut, Billotte admitted he was physically worn out and did not know how he could deal with the panzers crossing toward the Channel behind his armies. Indeed, at the beginning of the day the panzers were at St. Quentin and by the end of it at Peronne. Gort, who was receiving precious little information, orders, or guidance from Billotte, could see that his own rear echelon troops were likely to be chewed up and his supply lines threatened. Along with the French northern armies and the Belgian Army, his force was in danger of being cut off from the Allied armies around Paris and farther south.

Gort Considers Acting on His Own

It seemed to Gort that in this demoralizing situation he could press for one of three courses. The first was to fight the Germans advancing through central Belgium, thus running the risk of being cut off. The second, in the vein of Gamelin’s recent thinking, was to attack the Germans behind and to the south of him in an effort to reconnect with the Allied forces north of Paris. Such an attack would hopefully be coordinated with a French attack north from the Somme toward the same point. The third option was to move toward the Channel and fight from a beachhead, to be supplied by ships or, if need be, evacuated.

Even in thinking along these lines, Gort was passing into uncharted territory. He was supposed to be taking his orders from Billotte, not devising his own ideas for Allied strategy. Because Billotte was communicating only sporadically and the French high command was in such disarray, Gort felt he had to undertake some strategic thinking of his own. In this he was not totally out of line; his charge from the British War Cabinet, and endorsed by the French command, was that if he received an order from the French that he felt would endanger the BEF he could appeal to the British government. He was beginning to believe that the absence of orders in a time of confusion was indeed putting the BEF in mortal danger.

On the 19th, French Premier Paul Reynaud sacked Gamelin as the supreme Allied commander and replaced him with General Maxime Weygand, flown in from Beirut, Syria. Weygand suspended Gamelin’s plan and decided to take a tour of the front. For the next two days he was on the road. Thus, in a time of crisis and chaos, the Allied armies were virtually leaderless at the top.

When Churchill learned Gort was considering a retreat to the Channel as an option for the BEF, he was aghast. The prime minister had no conception that the situation was so serious. Retreat to the coast seemed like concentrating the armies into a “bomb trap.” He sent the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), Edmund Ironside, across the Channel to Gort’s headquarters to dissuade Gort from retreating. Ironside arrived there on the 20th.

When Ironside reached Gort, he ordered him to attack south. Gort had a high sense of duty, but he was skeptical at best. He told Ironside that seven of his nine divisions were fighting on the line and that to pull them out for an attack south would merely allow the Germans into the breach. Indeed, now that Ironside was closer to the action and confusion, he began to come around to Gort’s view. Ironside then met with Billotte and First French Army commander Georges Blanchard near the French town of Arras. He recognized their dejection and inability to devise a comprehensive counterstroke. “Situation desperate,” Ironside noted in his diary for this day. That evening, Guderian’s 2nd Panzer Division rolled into Abbeville, which lies at the mouth of the Somme. A million Allied soldiers were cut off from their comrades in the south.

Weygand, having concluded his tour, called a meeting of top commanders. He sketched out plans for an attack that differed hardly at all from Gamelin’s scheme of three days previous. By now, vital time had been lost. The plan called for the BEF and Blanchard’s First French Army to attack south near Arras in an attempt to link with French forces fighting north from the Somme. Coordination would be vital, but dire problems continued to plague the Allies. General Billotte, the man most knowledgeable of Weygand’s plan, suffered mortal injury in an automobile accident shortly after the meeting. Overall command of Army Group One passed to First Army commander Blanchard, whose energy was about exhausted. Communication across the German-occupied territory was tenuous.

Gort’s Counterattack is Rebuffed

Gort, never keen on the southward attack plan to begin with, nevertheless ordered parts of his two reserve divisions to the counterattack on the 21st. A strong French armored advance, which was to take place on the same day and alongside the British, was delayed.

The BEF attack near Arras comprised 74 tanks. They caught the SS Totenkopf (Death’s Head) Division traveling west in unarmored trucks following behind a panzer column. For a time, the British had it all their way, and the Germans fell into disarray. The British tanks, however, had traveled far from Belgium; their treads were worn, their radios dead. General Erwin Rommel, commanding the 7th Panzer Division, although concerned for a time, counterattacked with a very strong force. He used his 88mm antiaircraft guns against the British tanks. He enjoyed better communication with his air force, which sent Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers down on British infantry columns virtually unimpeded by Allied aircraft. Moreover, the French attack north hardly materialized beyond the marshaling stage and got nowhere.

By the end of the day, the British attack was contained. The Germans pursued but ran into the strong French armored force that was meant to have advanced alongside the British. Through the night the French heavy tanks chewed up the German armor, but with daylight, the German 88s and the Stukas began to turn the tide.

The British could not muster an attack on the 22nd and did not tell the French they were pulling out of the fight. The French attacked, but could not make progress. The drive south, although it had given the German commanders a disturbing shock, was blocked. Nevertheless, it had consequences far beyond its meager success, as would play out two days later.

Now along the Belgian-French border there were three mind-sets—four, if that of the Germans is included. The Belgians, pushed back with the French and BEF, were fighting for their homeland, but there was precious little of it not under German control. The French, very near their homeland or actually in it, were fighting for France, nearly all of which was still in French hands. The BEF was fighting for the Allied cause, but most especially for Britain, which was across the Channel. If Britain was to stay in the war, the BEF would have to survive. Although they were all fighting a common foe and pledged as Allies, the commanders of the three forces saw the situation and the possible solutions somewhat differently. Allied solidarity was beginning to crack.

The Germans believed they could do what their fathers could not: defeat the French, British, and Belgian armies. They were fighting for revenge and a greater German dominance in Europe. Their primary task was to encircle the enemy armies and force their surrender. They did not have a fractured command structure, but a monolithic one, unencumbered by either language differences or the irritating demand for consensus. Further, their morale was high.

Weygand was furious with Gort’s lack of success at Arras and of seeming to pull back for no good reason. On the 22nd, he met with Churchill, who had flown to Paris, and impressed the British prime minister with the viability of more attacks from north and south. This seemed reasonable to Churchill, who ordered Gort to comply. Gort had already committed his reserves to the Arras fight. Nevertheless, he said he would attempt another attack south, but that he could not be ready to launch it until the 26th.

Meanwhile, the Germans were broadening their corridor stretching from Sedan to the sea and strengthening it with infantry on the flanks. To Gort’s mind, if the attempt to pinch off the panzer head by slicing through at Arras failed, another attempt would likely fare no better. In his view, the million men of three nationalities cut off in the north would have to fight in their own pocket, supplied through Channel ports. They would have to make an impenetrable perimeter, but to do so they would have to retreat from their present positions and concentrate. From this shell the three armies of the three different countries with their three different outlooks would do what they could.

A Reprieve: Rundstedt Orders the Panzers to Stop

Then suddenly they had relief. Early on the morning of the 24th, Army Group A commander Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt called for his panzers to stop. He had several reasons. The panzers had been running hard for two weeks and about half of them were out of commission owing to battle damage or lack of maintenance. In addition, they had so outpaced supporting infantry that Rundstedt was afraid they were vulnerable to being cut off. If they paused, the infantry could catch up, protect the corridor, and solidify the gains.

Oddly, the blunted attack at Arras had much to do with this decision. Rommel had told Rundstedt that he believed (incorrectly) that he had been up against seven divisions. Rommel’s own 7th Panzer Division had been badly shaken during the fighting, some of the Germans fleeing in panic. Rundstedt worried that another such blow from the north, accompanied by a coordinated attack from the south, could cut the panzers off from their base. Indeed, the Allies were trying to organize these attacks but were too crippled with confusion to make a good job of it. Hence, the decision to stop the panzers and await the arrival of the infantry.

Hitler had traveled to Rundstedt’s headquarters to confer with him that day. Rundstedt gave his reasons for the order, and Hitler concurred. Colonel General Franz Halder, the chief of the German General Staff, and Walther von Brauschitsch, the Army commander in chief, were aghast and tried to work around the order, but to no avail.

Why Hitler agreed with Rundstedt and allowed the order to stand has been the subject of much debate. Again, there were good reasons for acquiescing to Rundstedt’s caution. With the Allied northern armies cut off from the southern ones, the northern forces became less of a priority. The important targets became Paris and the remainder of France. For these the panzers would be much needed; hence the rationale of husbanding their strength and preparing them for the long drive south.

Moreover, Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring implored Hitler to let his planes deal with the shrinking pocket, which even Churchill was calling a “bomb trap.” Göring, who no doubt wanted as much glory for himself as possible, said that his planes could dispose of the armies retreating to the coast. Possibly Hitler and other like-minded German commanders, being land- and not maritime-minded, believed that there was no escape once an army had its back to an ocean, that it was only a matter of time before destruction, starvation, or capitulation intervened.

Historians Ernest May and Karl-Heinz Frieser add to these. They believe that at this time Hitler was worried that too much of the glory would go to the Wehrmacht, whose leaders he did not trust. He therefore wanted to show his commanders who was in charge and felt this was one way of doing it.

In any event, Guderian reported later that he was furious and that the decision was a great blunder. Perhaps he was right. He was closer to the situation. Hitler and Rundstedt were removed from the confusion and chaos on the battlefield and perhaps overestimated the capacity of the northern Allied armies to resist.

The delay turned out to be a godsend for the Allied armies, especially for Gort and his BEF. The main effort to cut him off from the sea shifted to Army Group B, attacking with infantry from the north and east, and Gort was just able to hold them. Had he been more pressed with powerful tank forces from the west his lines might have crumpled.

The 25th was a critical day. Gort had hoped to put three divisions into the fight south, but pressure all along his line left him no choice but to offer two instead. Even these he was offering as a sort of token, but offer them he would. There was some hope. Blanchard was saying the French could put 200 tanks and two divisions into the fight. Then bad news followed bad news. The Belgian Army, which by now was fighting on the left flank of the BEF from the sea down to Menin, was beginning to crack. Moreover, Gort learned from captured German Sixth Army orders that two corps were going to hit the Belgian line hard.

Despite the fact that some Belgian units were fighting tenaciously, top Belgian commanders, even King Leopold, had been warning for days that they might have to pull out of the war. Gort was justifiably worried about this northern flank. If the Belgians collapsed, nothing would prevent Army Group B from reaching the coast near Ostend then marching south past Nieuport and Dunkirk to link up with Army Group A. That would cut off the BEF and the First French ˙ƒArmy from the sea and any source of supply, retreat, or evacuation.

Gort had nothing with which to bolster the Belgian line but the two reserve divisions he was about to launch on the attack south. If he sent them south as planned he risked being completely cut off from the Channel. If he sent them north to the Belgian line he would be abandoning Weygand’s plans, he would be disobeying Blanchard’s orders, and he would be acting on his own against the expressed intentions of his government. He would also be making a strategic decision for his country and the Allied cause.

The proposed attack south was intended to stagger the Germans to the extent that the French, British, and Belgians could rally where they were. Without such an attack, the only course was a beachhead around Dunkirk, and the only course from a beachhead under these circumstances, at least in Gort’s mind, was an evacuation by sea. It did not mean full abandonment of France. There was the possibility of British troops being rerouted back to more fighting in southern France, and this was, indeed, the eventual course for some British and French troops. It did, however, mean the end of the BEF fighting near the French-Belgian border.

At least this was Gort’s thinking. He did not express as much to Blanchard early the next day, but did tell him that he had redirected his two divisions to the north rather than sending them south. Blanchard agreed that both his forces and Gort’s would have to fall back. Blanchard saw the move as having the sea to their backs; Gort saw it has having the sea “to the front,” with the expectation of moving across it.

The Belgian’s Finally Crack Under the German Onslaught

So Gort was falling back to evacuation. Neither he nor the London government had to this point told Belgian King Leopold that the BEF intention was now evacuation rather than a fortress bridgehead. Leopold repeatedly asked for aid, air cover, and counterattacks by the BEF in the Belgian sector, but not much was forthcoming owing to the desperate state of British and French forces.

Leopold was being cornered into a time of dire decision, and it was to be political as well as military. Already the Dutch queen had fled to England, heading a government in exile. King Leopold was urged to follow her example, but he refused. He felt that he could best serve his country by remaining in Belgium and dealing with the Germans as best he could. Leopold’s decision to make a separate peace has been controversial ever since. His own government disassociated with it and, claiming itself the legitimate government of the country, set up in exile.

Late on May 27, King Leopold sent a message to Gort that his army could take no more and that he was ready to surrender. Gort, although he knew of the tremendous pressure on this front for days, expressed surprise, shock, and dismay. The Belgians held a line of 20 miles from the sea to the northwestern divisions of the BEF. If they capitulated and there was no one there to close the gap, German Army Group B would sweep into the Channel ports.

Leopold called for a truce with the Germans on the evening of the 27th, asking for terms. Hitler demanded unconditional surrender, which Leopold accepted. The Belgians were to lay down their arms at 4 am on the 28th. Their war was done.

Nothing Left to do But Evacuate

On the 28th Gort was determined to hasten his withdrawal, to concentrate his forces into a beachhead and thus assure that he was not cut off from the sea. He told Blanchard in a meeting that morning that he was intending, even ordered by London, to evacuate by sea. Blanchard was astounded, and Gort was surprised that this was the first Blanchard knew of an impending evacuation. Nevertheless, he urged Blanchard to coordinate the movements of the First French Army with those of the BEF.

Blanchard was not of the same mind. He felt the French should fight where they were, every day allowing a further strengthening of the French armies that could defend Paris and the south. Unlike Gort who saw the Channel as a road home, Blanchard saw it as a border beyond which he did not care to go. Moreover, Blanchard was skeptical of French or British ships being able to carry out an evacuation of the size needed for so many men.

Blanchard talked with a liaison officer from the First French Army, which was around Lille. Its commander, General Piroux, believed that most of the army was too exhausted to move. Blanchard then asked Gort if he intended to withdraw that night even if it meant moving without the First French Army. Gort said that he did. Five divisions of the First French Army were thus left on their own in and near Lille. They attempted a breakout, but the Germans had them surrounded with too much force. Fifty thousand French soldiers thus became prisoners of war. About half of the First French Army retreated to Dunkirk with the BEF.

Now there was no recourse. The BEF was definitely leaving the fight along the French-Belgian border. The French would have to salvage what they could for the continuing struggle for the body of France. The job at hand was to get as many soldiers off the beachhead as possible.

Many commanders believed this might run into the tens of thousands at best. What followed was the “miracle of Dunkirk.” More than 330,000 British and French, that is, most of the BEF and a good portion of the remnant of the First French Army, slipped away from the Wehrmacht’s talons.

Brooke C. Stoddard is the editor of Military Heritage magazine.

Enjoyed this article. I found it informative and always enjoy reading information on cause and effect of decisions made.

Tomorrow will be 80 years to the day when my Dad’s older Brother, a first Lt in Patton’s 712th Tank Battalion was hit by shrapnel from a King Tiger 88. Uncle Jim had his gunner fire a round from his M4 Sherman along with two other Sherman tanks under his command at the Tiger as it pulled out from a wooded area of the Ardennes. Uncle Jim told me that he watched through binoculars as the shells literally bounced off the Tigers turret area. His statement to me was that the Tiger stopped as he watched the turret maneuver their direction. Uncle Jim indicated that he radioed immediately for all the Sherman tanks commanders to retreat as a shell from the Tiger penetrated his Sherman tank while maneuvering full speed in reverse. The shell ripped the turret from the main body of the tank and killed all but he and his gunner. Uncle Jim while severely wounded pulled his gunner from the burning tank and both fell to the ground. My Uncle was struck by a 6″ piece of shrapnel that ripped through his right hip and out through his lower pelvis. Jim was awarded the Bronze Star for his gallantry that saved another member of his crew. He was not expected to live but was sent to the rear lines for surgery. Then was sent to London where he stayed for 6 months until he was well enough to head back to the States. Incredible was hero. He was selected to be one of Patton’s Pall Bearers at Patton’s military funeral. These guys were tough as nails