By Eric Niderost

Around 10 o’clock on the morning of December 13, 1937, New York Times correspondent Hallett Abend received an unexpected visitor: Rear Admiral Tadao Honda of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Abend was in Shanghai covering the Sino-Japanese War that had been raging since the previous July and, although unexpected, this visit was not entirely out of the ordinary. The American was in the International Settlement, a foreign enclave of the city that was ruled by a largely Anglo-American Municipal Council not subject to Chinese law.

As a journalist from a neutral country, Abend was well known to both Chinese and Japanese authorities, but it was soon clear that this visit was anything but a social call. Honda, who was a naval attaché with the Japanese embassy, appeared agitated, even nervous, as he breathlessly begged Abend to accompany him back to the Idzumo, a Japanese cruiser moored in the Whangpoo (now Huangpu) River. It seemed that Vice Admiral Kiyoshi Hasegawa, commander of the Japanese Third Fleet, wanted to see him on a “matter of grave importance.”

“I’m Afraid That We Have Sunk the Panay“

Scenting a story, Abend piled into Honda’s car for the short drive to the Honkew District. While technically part of the “neutral” International Settlement, Honkew was strictly a Japanese preserve, so much so it was nicknamed “Little Tokyo.” The American and his nervous companion alighted in front of the Japanese consulate, not far from where the Idzumo was moored.

Abend was quickly ushered into Admiral Hasegawa’s cabin, where he found his erstwhile host talking with Rear Admiral Teizo Mitsunami. After the usual courtesies were exchanged, Hasegawa came right to the point. “I’m afraid,“ he confessed, “that we have sunk the Panay!” The Panay was a United States Navy gunboat, part of the Yangtze River Patrol whose primary mission was to safeguard the lives and property of Americans along China’s great waterway. For the next 20 minutes or so, Abend pressed the two Japanese officers for details but was frustrated in his attempts to get at the truth.

The two Japanese naval officers seemed to follow a script as they expressed formal apologies and mouthed veiled hints that the Japanese Army, not Navy, was responsible for the Panay’s demise. “But who,” insisted Abend, “ordered the bombing of the Panay?” It is a question that resonates to this day, even after the passage of more than 70 years.

Patrolling the Yangtze on the USS Panay

The Yangtze River Patrol was an outgrowth of China’s turbulent history from the 1840s to World War II. China was helpless giant, weak and powerless in the face of foreign domination and internal dissension. In the 1920s and 1930s China’s plight reached its nadir. Bandits swarmed though the countryside, terrorizing peasants and plundering with savage abandon. Warlords vied for power, carving out private fiefdoms in defiance of the central government, which was weak, often corrupt, and divided.

In the late 1920s Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) fought a series of bloody campaigns against the Chinese Communists under Mao Tse-tung. With China literally tearing itself apart, ultranationalists in the Japanese military sensed an opportunity to enlarge Japan’s empire. In 1931, the Japanese seized the northern Chinese province of Manchuria and renamed it Manchukuo. The last emperor of China, Henry Pu Yi, was installed as the puppet ruler of an “independent” Manchukuo, but few in the international community were fooled by this clumsy window dressing. Manchukuo was a puppet of the Tokyo government.

The USS Panay (PR-5) was one of six new gunboats that were specifically designed for China service. The Panay was built by the Kiangoan Dockyard and Engineering Works in Shanghai. Named for an island in the Philippines, Panay slid down the ways on November 10, 1927, and was formally commissioned on September 10, 1928.

The gunboat’s main battery consisted of two 3-inch, 51-caliber guns with telescoping sights. They were high-angle guns that could readily silence most opposition that the boat was likely to encounter along the river’s muddy shore. They were complemented by eight 30-caliber machine guns that were paired amidships. Mounted on armored shields that could swivel, the machine guns were of World War I vintage but still highly effective if manned by trained naval personnel.

Panay escorted American merchant ships up and down the river and provided sanctuary for American citizens when needed. The political situation was so confused at times that it was hard to tell who was the enemy—communist partisans, rogue nationalists, warlord troops, or simply disgruntled bandits cheated of their prey. But bullets have no political allegiance, and Navy men, nicknamed “river rats” or “old China hands,” responded in kind when the lead began to pepper the decks.

In 1931, Lt. Cmdr. R.A. Dyer, then skipper of the Panay, reported, “Firing on gunboats and merchant ships have [sic] become so routine that any vessel traversing the Yangtze River, sails with the expectation of being fired upon.” Dyer laconically added, “Fortunately, the Chinese appear to be rather poor marksmen and the ship has, so far, not sustained any casualties in these engagements.”

A Disease of the Skin Versus a Malady of the Heart

By 1936, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek had effectively united most of the country under the banner of the Nationalist Party. He still looked on the communists as a greater threat than the Japanese. Adapting an old Chinese proverb, he said the Japanese were only “xuan jie zhi ji,” a “disease of the skin,” while the communists were “xin fu zhi huan,” a “malady of the heart.”

But Chiang was kidnapped by warlord General Chang Hsueh-liang in December 1936, and was presented with an ultimatum that he find common cause with the communists against the Japanese. Some wanted Chiang killed, but others, notably Communist Party leader Chou En-lai, argued the generalissimo should be spared. He was the one figure who had enough stature to unite the whole country in an anti-Japanese crusade. Chiang was spared, and he readily agreed to a “united front” against Japanese aggression.

The China Incident

These complex political wranglings were not lost on the Japanese military, which realized that a united China might jeopardize their dreams of empire. They quickly engineered the “China Incident” around Peking (Beijing) in the summer of 1937, which quickly blossomed into a full-scale war.

Fighting started around Shanghai in August. Because the International Settlement and the French Concession were major enclaves of Western power, Chiang brought in his best troops to make a stand at the great city. Britons and Americans in particular would have “ringside seats” in the coming contest, and it was hoped a heroic defense would soften neutrality and cause the West to intervene on the side of China.

It proved a vain and forlorn hope. Many Americans, particularly American missionaries, were genuinely sympathetic to the Chinese cause, but the cares of the Depression, plus a nagging feeling that the United States had been “tricked” into World War I, bred a powerful isolationism that was almost impossible to overcome.

Admiral Harry E. Yarnell, commander in chief of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, did not care too much for power politics or the niceties of diplomatic protocol. His duty was to protect American lives and property in China, and he was going to do all in his power to accomplish that goal. His request for the heavy cruisers San Francisco, Tuscaloosa, Quincy, and Vincennes was flatly turned down as too provocative by the U.S. State Department, but on September 19 the 6th Marine Regiment arrived at Shanghai to bolster the International Settlement’s defensive perimeter.

The 6th Marines joined the 4th Marines, a regiment that had been posted in Shanghai since 1927, and together they formed Brig. Gen. John C. Beaumont’s 2nd Marine Brigade. Leathernecks took up positions all along the International Settlement boundary, especially along the vulnerable south bank of Soochow (Suzhou) Creek. Miles of barbed wire were strung, sandbags stacked, and machine-gun emplacements manned.

The U.S. ambassador, Nelson T. Johnson, was in Nanking (now Nanjing), roughly 145 miles northwest of Shanghai, carefully monitoring events. Nanking was the capital of China at the time, the political heart of the nation. Johnson was an “old China hand” who spoke the Mandarin dialect and had served in various diplomatic posts since the early 1900s. He favored the Chinese cause and advised against invoking the various neutrality acts that were on the books. If the United States officially recognized that a state of war existed between Japan and China, these laws would forbid giving aid to belligerents.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt never recognized the Sino-Japanese War, which enabled the United States to sell arms to China—some $9 million worth in 1938 alone. Roosevelt was genuinely sympathetic to China, but the president was a pragmatist who wanted to protect his own country’s interests. Strict enforcement of the neutrality laws would have cut off Japanese trade as well. In September 1937, for example, the Japanese contracted for 500,000 tons of American oil. Such deals were always welcomed in an America still ravaged by the Depression.

Withdrawing Personnel from Nanking

On September 19, the Japanese announced that Nanking would be bombed the very next day. Because the bombing raid was going to be a heavy one, the Japanese wished to warn foreign nationals to avoid third-party casualties. Any neutral who persisted in staying on did so at his own risk. Ambassador Johnson took the Japanese at their word and evacuated the American embassy personnel to the gunboat USS Luzon.

The Luzon was anchored in the middle of the broad Yangtze River, presumably out of harm’s way, though stray bombs were always a danger. Johnson and the embassy staff waited for “hell to descend,” but the appointed time came and went without incident. On the morning of September 21, as Johnson prepared to return to the embassy, he was interrupted by the mournful wail of air raid sirens. Japanese bombers filled the sky, their deadly payloads unleashing a rain of death and destruction.

Johnson and his staff watched helplessly as Nanking was pummeled without mercy and without constraint. Buildings were transformed into gutted shells, and black coils of smoke rose into the air. When the all clear was sounded, the American ambassador went ashore only to find his actions had sparked new controversy. The Chinese felt he had run away, and missionaries and other like-minded Americans agreed, feeling the ambassador was too afraid of offending the Japanese.

Johnson was a career diplomat with a thick skin who took little offense at the allegations. His primary mission was to protect Americans living and working in China by maintaining a strict impartiality. Above all, he was to avoid situations that might lead to war with Japan. The potential bombing of the U.S. embassy and the loss of lives among American diplomatic staff might well trigger just such a war. Though no coward, Johnson had felt the evacuation was justified under the circumstances.

Shanghai fell in mid-November 1937, after a hard and bloody three-month battle. The Japanese, who had expected an easy victory, were furious at their perceived loss of face. The battered but unbroken Chinese armies withdrew up the Yangtze Valley, quickly followed by Japanese forces in close pursuit. Chiang Kai-shek held a series of high-level meetings to discuss the Japanese advance. Should Nanking be defended or abandoned? The generalissimo’s advisers were deeply divided, but in the end it was decided the city would be defended, if only to uphold national honor.

The Chinese Army was in disarray, filled with raw recruits hastily conscripted to replace the seasoned soldiers lost in Shanghai. Chiang Kai-shek was nothing if not a realist, so he gave orders for Chinese government officials to pack up and leave the city. A temporary capital would be established in Hankow, about 400 miles upriver from Nanking. If Hankow was threatened, then the government would move again to remote Chungking (now Chongqing).

Ambassador Johnson boarded USS Luzon on November 21, 1937, for the journey to Hankow. There was little he could do under the circumstances; Chinese government officials were leaving in droves, and Nanking would soon be a battleground. Most of the embassy personnel were evacuated, but a skeleton staff remained behind under Senior Second Secretary George Atcheson, Jr. Other embassy members who remained on duty included Second Secretary J. Hall Paxton, military attaché Captain Frank Roberts of the U.S. Army, and embassy secretary Emile Gassie.

Panay‘s Convoy Moves Up River

The Panay was designated a station ship, there to provide both a radio link to the outside world and a place of refuge should the need arise. Indeed, many Americans were still in the city, including newspaper and magazine journalists, businessmen, teachers, and missionaries. The Panay was for them as well as for diplomatic staff. The Chinese government finally informed the American embassy that the situation had seriously deteriorated. It was time to close the embassy and evacuate the remaining personnel.

All American citizens were strongly advised to leave Nanking; if they remained they would do so at their own risk. Once Panay sailed, they would be on their own. By Saturday, December 11, there were about 13 civilian refugees aboard, including four members of the embassy staff, four American nationals, and five foreign nationals. Some Americans elected to stay—people like missionary W. Plumer Mills and surgeon Dr. Robert Wilson of the Nanking University Hospital. They were to become witnesses of the infamous Rape of Nanking, where some 300,000 Chinese died at the hands of bestial Japanese troops.

About 2 o’clock in the afternoon of December 11, the Japanese staged a major bombing raid on Pukow, just across the river from Nanking. Panay’s skipper, Lt. Cmdr. James J. Hughes, decided to move up the Yangtze when some bombs landed perilously close to the gunboat. Panay moved about a mile upriver to the San-Chia-Ho anchorage. A cluster of ships anchored there, including two British gunboats, a couple of steamers, and three American Standard-Vacuum Oil tankers. There were also smaller auxiliary craft hovering around the larger vessels like ducklings around their mother.

The San-Chia-Ho anchorage soon came under Japanese artillery fire, so it was decided that the Anglo-American convoy would travel an additional 13 or so miles upriver to a safer location. As they proceeded up the Yangtze, Japanese artillery shells continued to rain down from nearby shore batteries. The barrages were wild and inaccurate, but after two miles of such treatment all aboard were on edge.

Pushing for an International Incident

Apparently the artillery fire was ordered by a Colonel Kingoro Hashimoto, one of those rabid ultranationalists that infected the Imperial Japanese Army like a plague. Hashimoto was only a colonel, but he had powerful connections within the military and had been one of the instigators in a series of Japanese political assassinations the previous year. A strong advocate of Japanese conquest, he chafed under civilian rule and hoped that a war with the United States would give the army a completely free hand in China.

Sunday, December 12, 1937, was a clear and sunny day, the bright azure sky giving a feeling of calm and security. The morning reverie was rudely interrupted by Japanese artillery fire at about 7:30 am. Hughes had to find a safe berth for both his gunboat and the oil tankers and auxiliary craft that looked to him for protection. When Hughes notified the British gunboats he was going farther upriver, they strongly advised him to stay put. He politely rejected the idea.

The Panay got underway at about 8:25 am; it was followed by the three Standard-Vacuum Oil Company tankers. The vessels, named Mei Ping, Mei Hsia, and Mei An, had many Chinese crew members who were understandably apprehensive. Japanese troops might stop the convoy and board at will. The Japanese were unpredictable; they might take it into their heads that the Chinese sailors were soldiers in disguise and shoot them all.

That same morning HMS Ladybird was hit by shells from Japanese shore batteries. The British gunboat was damaged and had one sailor killed and several wounded. The shelling was evidently Colonel Hashimoto’s doing. He appeared determined to provoke an international incident.

Unaware of what was happening to the British, the American convoy steamed upriver without incident. Suddenly Japanese soldiers were spotted along the shoreline waving flags. It was a signal to stop, so the convoy hove to as ordered. A Japanese launch filled with armed soldiers soon appeared and made its way to the Panay. Once alongside, a samurai sword-carrying officer clambered aboard, followed by two armed soldiers. This armed intrusion was a breach of etiquette, but Commander Hughes chose to ignore it.

Lieutenant Sesyo Murakami wanted to know where Panay was going and the character of its mission. He also wanted Hughes to disclose the whereabouts and movements of any Chinese troops he might have encountered en route. The American officer said nothing, reminding Murakami that the United States was neutral. Murakami also wanted to search Panay and the tankers for Chinese soldiers trying to escape Nanking. Hughes politely but firmly refused permission. Shifting gears, Murakami became almost friendly, asking Hughes to come ashore for a courtesy visit. Panay’s skipper declined the offer.

The convoy was allowed to proceed unmolested and at about 11 am found a good anchorage off the entrance to Hohsien Channel. The spot was about 28 miles upriver from Nanking. The Yangtze was fairly wide there, a veritable moat to safeguard the convoy from Japanese intrusion. Or so it seemed. Hughes radioed his position to the U.S. consulate in Shanghai, which would relay the information to Japanese authorities.

Hashimoto’s False Report

The Panay was a sparkling white, but her twin smokestacks were a contrasting buff color. There was little or no wind, so its large American ensign hung limply at the mainmast gaff. The ship was well marked, however, by large American flags painted on the tops of her upper deck awnings. It was getting near lunchtime, so passengers and crew began to relax and turned their thoughts to food. The ship’s galley produced a hearty lunch, and after a big meal many decided it was time for an afternoon nap.

Eight crew members from Panay were given permission to visit the tanker Mei Ping, where they drank beer and generally enjoyed themselves. Captain Roberts went over as well, less for the beer than to hear the 1 o’clock Shanghai broadcast from the ship’s radio.

The day was unusually warm for December, and people sought places to sleep off the big lunch. Norman Soong, a Chinese-American news photographer who was working for the New York Times, found a likely spot for a snooze but made sure his fully loaded camera was at hand. Chief Boatswain’s Mate Ernest Mahlmann took off his clothes and stretched out in a storeroom below decks. His regular CPO berth had been commandeered by one of the passengers, but Mahlmann could sleep almost anywhere.

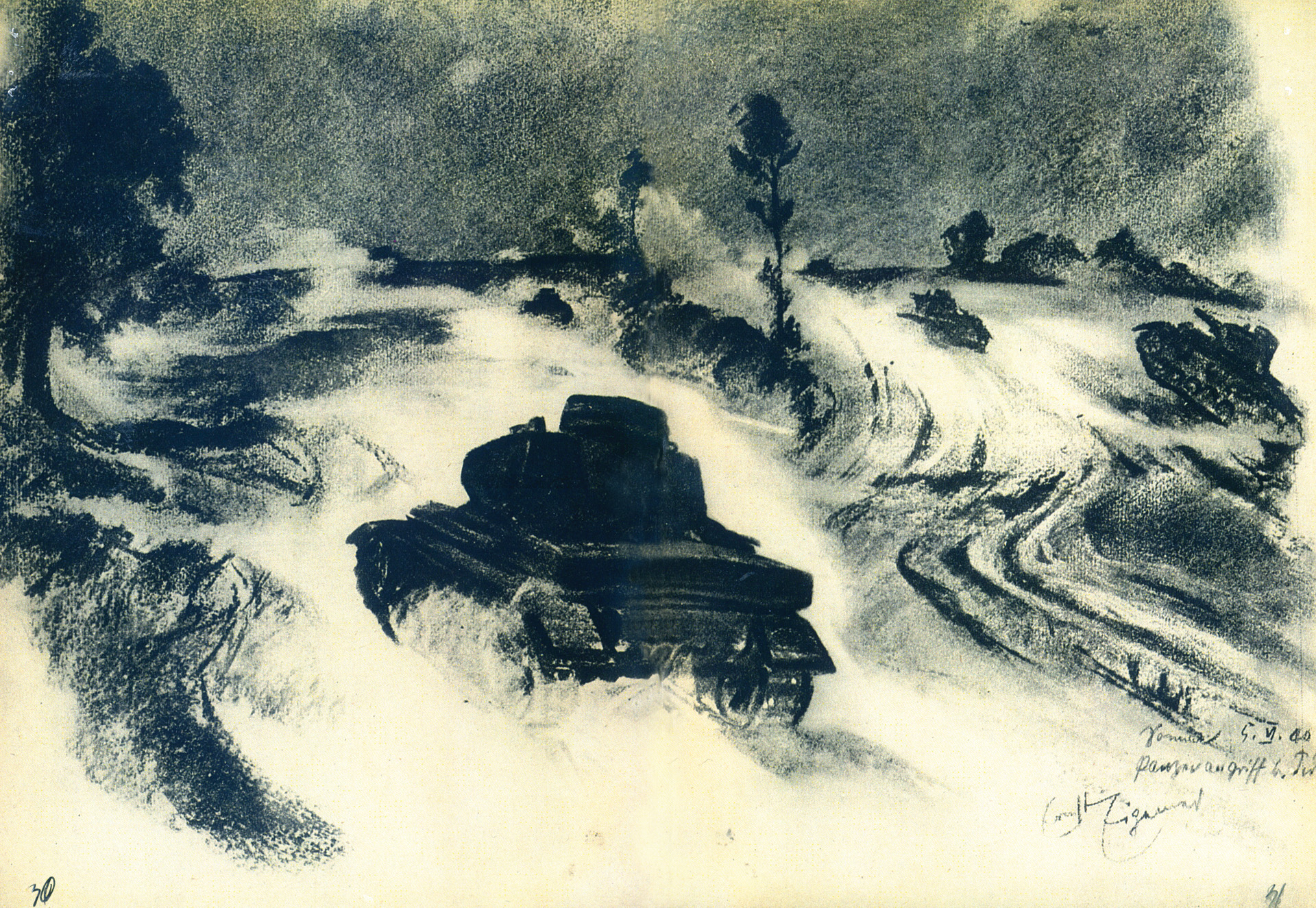

Earlier that morning, Colonel Hashimoto was busily engineering a plan that would ultimately end in the damaging of British gunboats and the sinking of the Panay. The Japanese Army lacked planes in the area, so it had to rely on the services of various naval aviation units. Hashimoto knew that there were standing orders forbidding attacks on river traffic for fear of hitting neutrals. To overcome that obstacle the colonel reported that his troops had spotted 10 Chinese troop ships fleeing Nanking.

Orders Written in Blood

The Japanese Navy took the bait at once. The Navy pilots had been bored and frustrated over the lack of targets. Now they were presented with a great opportunity. An attack force was hastily assembled from the 12th and 13th Air Groups. The 12th Air Group contributed nine fighters and six dive-bombers for the effort. The 13th Air Group’s Lieutenant Shigeharu Murata led three Mitsubishi type 86 level bombers to the mission, while Lieutenant Masatake Okumiya had six dive-bombers.

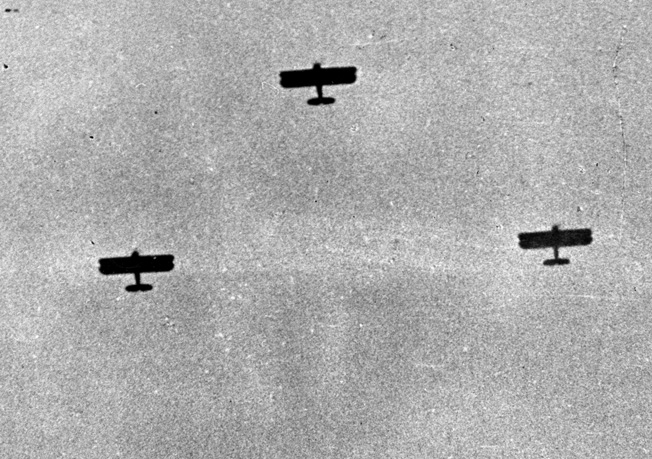

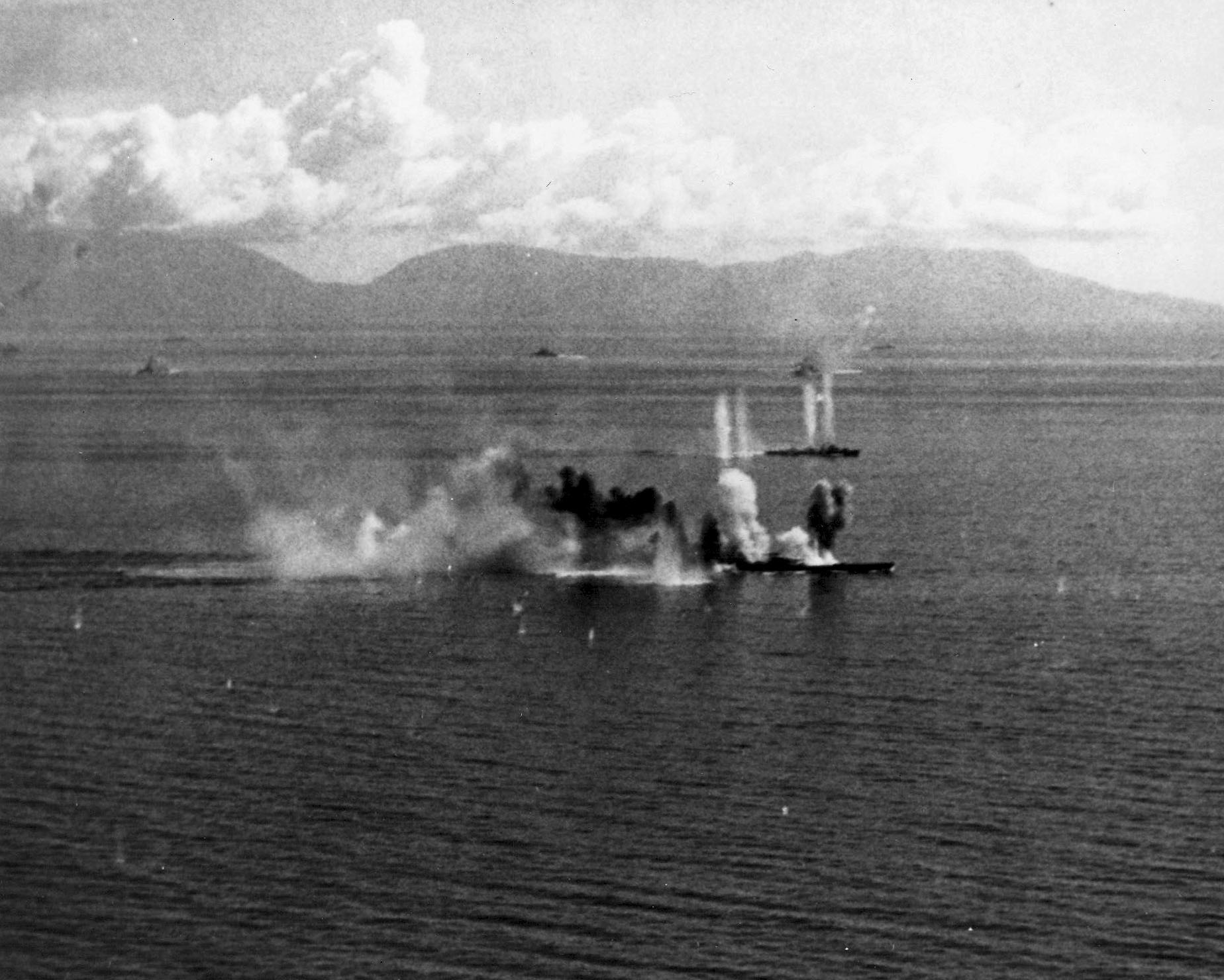

The Japanese were so eager to come to grips with the enemy that little thought had been given to a precise attack plan. In fact, Okumiya and Murata were friendly rivals, each almost desperate to win a coveted unit citation for his men. The dive-bombers flew at about 12,000 feet, the level bombers 1,500 below them in a V formation. The level bombers got to the target first and quickly unleashed their payloads.

The Panay’s lookout spotted the Japanese planes, dark shapes standing out in bold relief against a cloudless sky. It was 1:37 pm, Sunday, December 12, 1937, and within moments all hell was going to break loose. Commander Hughes and Chief Quartermaster John Lang went to the bridge to see what was going on. Several of the journalists on board had also heard the lookout’s cry and came outside to have a look. If they scented a story, they got more than they bargained for.

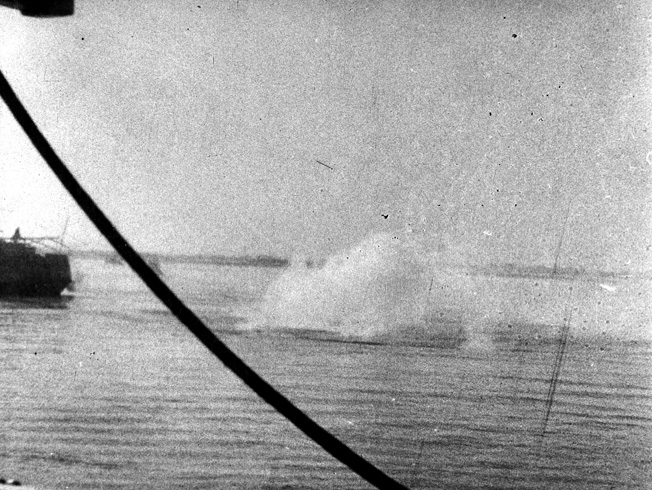

Hughes was astonished. The Japanese planes were headed toward the Panay and its little band of tankers and auxiliary vessels. Were they going to actually attack? It was impossible! But before Hughes could react, the first Japanese bomb hit Panay just forward of the bridge. The force of the blast picked the commander up and threw him against a pilothouse wall, causing him to momentarily lose consciousness. This bomb was one of 18 that were initially dropped by the level bombers.

When Hughes came to, he immediately realized the ship was badly hurt. The bridge was wrecked, the foremast was down, and the radio room a total loss. The forward 3-inch gun, one of two such guns that made up the Panay’s main battery, was completely smashed. Hughes himself was in pretty bad shape, with white-hot pain coursing though his body when he tried to move. His hip was fractured.

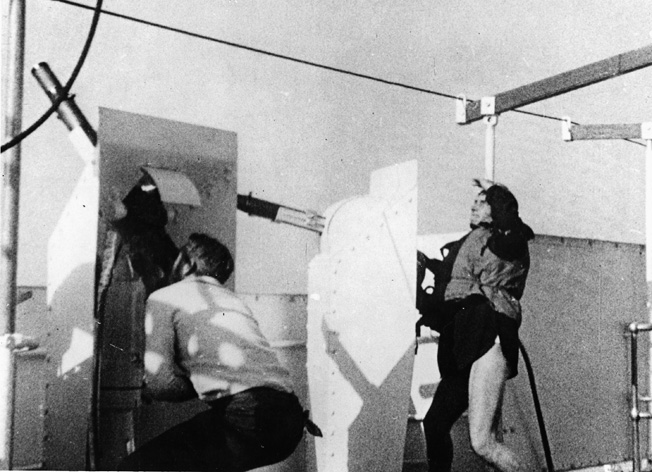

A second bomb soon completed the work of the first, lacerating what remained of the radio shack and toppling the foremast stump into the water. Since Hughes was incapacitated by wounds, tactical command now shifted to the ship’s executive officer, Lieutenant Arthur “Tex” Anders. The XO was badly wounded by shrapnel that was lodged in his throat. The raw, bloody wound made speech impossible, so Anders wrote orders on bulkheads and on a chart. Anders’s hands and fingers were badly cut, so the scribbled notes were often daubed with his own blood.

Professionalism on Board the Panay

Though surprised by the sudden attack, Panay’s crew responded with coolness and professionalism. Chief Malhmann ran up on deck and manned one of the ship’s machine guns. The vintage Lewis was soon spitting lead at the Japanese planes, the doughty chief pausing to take careful aim after each burst. Nobody seemed to notice, last of all the chief himself, that he still had no pants on!

The civilian journalists aboard the Panay were far from idle. When the attack began, New York Times photographer Norman Soong was napping on deck, his jacket rolled up for a pillow. He was rudely awakened by the rain of Japanese bombs that exploded all around him. Drenched with river water from the near misses, Soong started snapping pictures at great risk to his own life.

Norman Alley of Universal and Eric Mayell of Fox Movietone News were also busy recording the event with newsreel cameras. They managed to get some dramatic footage, including bomb detonations and close views of silvery Aichi D1A1 biplane dive-bombers swooping down. Alley and Mayell seemed to have charmed lives, but not everyone was so lucky. Italian correspondent Sanro Sandri was hit in the eye by a metal fragment as he followed Alley up a ladder.

Panay’s defense was hampered by the loss of the forward 3-inch gun. The stern gun was not able to fire because it was blocked by the awning structure. The ready ammunition lockers were empty since no attack had been anticipated. Once the aerial assault began, it was too late to bring ammunition from below decks. To do so would have meant opening the hatches—an unwise move that would have compromised the ship’s watertight integrity.

At the moment, however, any debate on the ship’s watertight integrity was moot. Panay was badly damaged and taking on water. Still bravely giving orders on the smashed bridge, the bloodied Lieutenant Anders wrote a directive for the ship to get underway and beach itself. This was impossible because an oil line was cut and Panay could not raise steam.

Blowing the Tankers

In the meantime, the Japanese planes from the 12th Air Group joined the attack, their attention focused on the oil tankers. The hapless trio was anchored near the Panay, the Mei Ping only about 100 yards on the gunboat’s starboard side. The ships immediately got underway, hotly pursued by Japanese dive- bombers. The Mei Hsia tried to render assistance to the Panay en route, but it was waved away. The gesture was appreciated, but the idea of a highly combustible oil tanker right alongside did not cheer the hard-pressed Navy crew.

Eventually, Mei An was beached on the northern bank, while Mei Hsia and Mei Ping secured a spot on the Kaiyuan pontoon on the southern shore. Ironically, there were Japanese soldiers stationed at Kaiyuan, and once the tankers reached their position they too were in the line of fire. The brown-clad soldiers frantically waved Japanese flags, but their countrymen refused to break off the attacks. Several soldiers were killed or wounded by friendly fire, and the tankers were destroyed.

Abandoning Ship

Hughes knew he had few options. The ship had no power and was taking on water fast. There were many wounded. Hughes himself was in great pain, his face blackened by smoke and soot. At about 2 o’clock he gave orders to abandon ship. The gunboat’s two sampans started to ferry wounded to the north shore, and gratings were tossed into the river as a kind of life-preserving flotation device. The Japanese attack was winding down, but the sampans were strafed as they tried to reach shore, resulting in more casualties.

Hughes protested when he was put into one of the boats for the trip to shore. They might be hundreds of miles from the sea, but Hughes wanted to uphold the time-honored tradition that a ship’s master be the last to leave a stricken vessel. It was approaching 3 o’clock, and the Panay was in its death throes. She was going down by the head, with some compartments flooded with water up to six feet deep. The forward decks were awash; it was now only a matter of time.

Ensign Denis Biwerse was the last man to officially evacuate the ship, but Chief Mahlmann and Machinist Mate First Class Gerald Weimers went back to fetch sorely needed stores and medical supplies. As they left, a Japanese launch filled with soldiers machine-gunned the Panay, boarded her, then departed the scene. At 3:45, the Panay rolled to starboard and sank in about 80 feet of water. The gunboat was the first American naval vessel to be sunk by aircraft in combat conditions.

Organizing the Survivors

The survivors were now hiding in the reed- choked marshes that lined the banks of the Yangtze. There was a need to take cover because Japanese intentions were still unclear. They might want to kill the survivors to finish the job. One sailor, ship’s storekeeper Charles Ensminger, had died during the attack. Lieutenant Charles Hulsebus and Italian journalist Sandri died of wounds later. Captain C.H. Carlson of the tanker Mei Hsia also was killed, which brought the total number of fatalities to four.

The survivors had no food, few supplies, and little medicine. About a dozen men were seriously injured, including the Panay’s skipper, and many more sustained minor wounds. The nights were bitingly cold, and the survivors had no shelter and inadequate clothing. At least one crewman was in shock. The bright spot in this litany of gloom was the fact that the doctor aboard, Lieutenant Clark Grazier, was unhurt.

Virtually all the Panay’s officers were badly wounded, and the crisis demanded active leadership. Under the circumstances Hughes delegated Captain Roberts to lead the surviving party. He had a working knowledge of Chinese, which was also a decided plus.

Second Secretary Paxton was sent to summon help; he was accompanied by Radioman First Class Andrew Wesler and a Chinese messboy named Wong. Wong was there to hedge their bets because he was fluent in the local dialect, and the Chinese might not understand Paxton’s Mandarin.

Paxton, who had a badly injured leg, rode on a local farmer’s horse, a sorry nag that plodded along with an uneven gait. Eventually, the party reached Hohsein, where there was a telephone. Paxton hired a rickshaw to go to Hankow, while Wesler, who was nursing an injured ankle, mounted the horse and returned to the survivors to tell them the news. Wesler also brought Chinese bearers along to help carry the wounded. The next three days were touch and go for the ragged, pain-wracked survivors. They hid from circling Japanese aircraft, not knowing these planes were actually performing search-and-rescue duties.

The local Chinese were poor villagers for the most part, and though they were somewhat fearful of Japanese retaliation they freely gave all they had. Panay survivors gratefully ate rice and drank cup after cup of bitter tea. After three days of fear and hardship, the survivors were picked up by the Ladybird and Panay’s sister gunboat, USS Oahu. They eventually reached Shanghai, where they were debriefed by Admiral Harry E. Yarnell aboard his flagship, the heavy cruiser USS Augusta.

“Deeply Shocked and Concerned”

President Roosevelt was outraged when he heard of the Japanese attack on Panay. Secretary of State Cordell Hull was scheduled to meet with Japanese Ambassador Hirosi Saito at 1 o’clock, so the president lost no time in sending a memorandum to Hull that expressed his dismay in no uncertain terms. The note, typed on White House stationery and dated 12:30 pm, December 13, 1937, did not mince words. Secretary Hull was instructed to tell the Japanese ambassador “that the President is deeply shocked and concerned by the news of indiscriminate bombing of American and other non-Chinese vessels on the Yangtze.”

The memo further expected that the Japanese government render “full expressions of regret and proffer of full compensation,” and that “methods guaranteeing against a repetition of any similar attack in the future” be established. The memo was initialed “FDR” in a bold hand. Roosevelt held a series of cabinet meetings to discuss the issue. There had to be some way of curbing Japanese aggression in Asia. He secretly contacted the British government and suggested a joint naval blockade of the Japanese Home Islands. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain rejected the idea out of hand. Chamberlain disliked Roosevelt personally, felt the New Deal was a farrago of half-baked economic theories, and considered the Americans to be totally unreliable. If political push came to diplomatic shove, the prime minister felt the Americans might well leave Britain holding the bag.

The Japanese government moved quickly to avert any possibility of war with the United States. Formal apologies were publicly expressed, and on April 22, 1938, the Japanese government paid $2,214,007.36 as settlement for the Panay, the loss of the three tankers, personal losses, and casualties. These gestures did much to placate Congress and American public opinion. Some of the more isolationist politicians wondered why the U.S. military was in China in the first place. If all American forces were withdrawn, there would be no repetition of the Panay incident.

Roosevelt knew that in 1937 the United States was not prepared for war with Japan. The British had rejected any joint punitive action, and isolationism was still a powerful force within American society. It was a bitter pill, but the Roosevelt administration decided to accept the Japanese apology and later financial compensation.

There was one problem, however. Norman Alley of Universal had shot a lot of film during the attack, and some sequences showed Japanese dive-bombers flying just a few hundred feet above their intended victims. Roosevelt personally asked Alley to delete about 30 feet of the most incriminating footage just prior to its public release into American movie theaters. Those crucial 30 feet of film exposed Japanese claims of ignorance as lies and thus were too inflammatory. Alley granted the president’s request.

Mixed Reactions in Japan

Many years later, Commander Okumiya wrote an account of the Panay affair that claimed that he and his squadron did not recognize the American gunboat. Okumiya insisted that the Japanese pilots thought they were attacking fleeing Chinese ships loaded with enemy soldiers. That may well be, but troubling questions remain. Why didn’t the dive-bomber pilots see the American flags that were displayed at several points? Even if they did not see the flags on their initial run, why weren’t the Stars and Stripes spotted as the attack progressed?

The ultranationalists within the Japanese military were unrepentant. If anything, men like Colonel Hashimoto were disappointed that major hostilities had not broken out between the United States and Japan. Rear Admiral Mitsuzawa, commander in chief of the Japanese Imperial Naval Air Forces in China, was relieved of command and sent home. Admiral Hasegawa also accepted responsibility, though there is no evidence he was involved in any way. Colonel Hashimoto was also sent home, but this was window dressing and involved little real disgrace. It was said that Hashimoto was a member of the secret Black Dragon Society, a group of hard-core nationalists who actively worked for the establishment of Japanese hegemony in Asia.

The Japanese people were not sympathetic with their military, and the American embassy in Tokyo was flooded with expressions of regret and sorrow. Tokyo schoolchildren contributed $10,000 in pennies for a Panay victim relief fund. A young Japanese woman even cut off her hair as a gesture of repentance and mourning and gave the tresses to the American ambassador. The ultranationalists in the Army and government were unmoved by these popular gestures; they were determined to establish Japanese hegemony in Asia as almost any cost.

The Turning-Point of U.S. Japanese Relations

The Panay incident marked a significant turning point in U.S.-Japanese relations. Before Panay, the Roosevelt administration was mildly pro-Chinese but too preoccupied with domestic affairs to resist Japanese aggression. After Panay, American foreign policy took steps, halting at first but gradually gathering momentum, to actively oppose Japanese conquest of Asia.

The isolationists responded by trying to introduce the so-called Ludlow Amendment to the Constitution. If adopted, this would have required a nationwide referendum before the nation would go to war. The one exception would be if American soil were actually invaded. Roosevelt lobbied hard to defeat the measure, which was rejected by the House of Representatives on January 10, 1938.

Roosevelt’s response was both public and private. He privately explored ways to freeze Japanese assets in the United States, but these probes were premature and came to nothing. In February 1938, the venerable Plan Orange was dusted off and revised to include a possible naval blockade of the Japanese Home Islands. Plan Orange, which formulated U.S. strategic objectives in the Pacific in the event of war with Japan, had been around in various forms since 1919.

On a more concrete, public level Roosevelt enthusiastically supported the Vinson-Trammel Naval Expansion Act, a $1.1 billion expansion of the United States Navy that would increase America’s two-ocean fleet by 69 vessels over 10 years. The most important part of the measure, at least in retrospect, was the increase of the nation’s aircraft carrier force. New carriers like Yorktown and Enterprise were going to play a significant role in the Pacific War to come.

The Panay incident was the first step on the long road to war. It was as if the loss of the gunboat awakened a somnolent Roosevelt administration, raising awareness that Japan was just as great a threat as Hitler’s Germany. The embattled group of “river rats” aboard Panay had not fought in vain.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments