By John J. Geoghegan

It is sometimes difficult to understand just how immature aviation was in the 1920s and 1930s. Everything about flying was new. Planes sported two sets of canvas-covered wings, had limited navigational ability, and had significantly less ocean-going range than a traditional destroyer. After their debut in World War I, planes held promise as instruments of war, but air tactics were still being refined and the planes themselves were unreliable, evolving, and still unproven. They may have been safe enough to carry mail, but not paying passengers—to say nothing of soldiers. The Air Force did not even have its own branch of the service until 1947.

Nevertheless, after World War I there was a strong feeling among certain members of the United States military that rigid-framed airships, or dirigibles, had a great deal of potential as instruments of war. Anything seemed possible during the quickly changing period of aviation. Between 1923 and 1933, the U.S. Navy’s Lighter Than Air (LTA) program produced four such dirigibles. At the time, they were the largest, most expensive aircraft ever built and were spectacular to behold. And though the dirigible seems in retrospect like something of a white elephant, for its time the LTA program was daring, imaginative, and highly innovative.

The Dirigible Craze

Dirigibles seemed poised to surpass trains and ocean liners as a better, faster form of transportation, especially across the Atlantic Ocean. The American military had seen the tactical success the Germans achieved using blimps during the Great War, and it acquired what would become the Los Angeles (ZR-3) as war reparations from Germany for study and experimentation. The public was also intrigued by the behemoths. They were especially captivated by the German Graf Zeppelin, which carried passengers from Europe to the United States, Brazil, and Japan long before commercial aviation was a going enterprise. Indeed, the 1930s saw a craze in America for all things dirigible. Airship designs became an integral part of Art Deco style and could be found on plates, pins, postmarks, and neckties. Newspapers lavished detailed coverage on each transcontinental crossing as if it were an Apollo program moon shot, and miniature Graf Zeppelin children’s toys, fashioned out of tin, were wildly popular.

The Navy’s dirigible program produced the USS Shenandoah in 1923, the USS Los Angeles in 1924, the USS Akron in 1930, and the USS Macon in 1933. The Macon, at 785 feet long, was literally the queen of the skies. To put her size into perspective, the Macon was three times longer than a Boeing 747, 971/2 feet shorter than the Titanic, more than 15 stories tall, and four times the length of modern-day Goodyear blimps. She even edged out Germany’s Graf Zeppelin in terms of size. Like the Saturn V rocket, Navy dirigibles were the high-tech aircraft of their day. The Macon, the last of the Navy’s dirigibles, was built at a cost of $2.5 million by the Goodyear-Zeppelin Company of Akron, Ohio, a joint venture between the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company and the Zeppelin Company of Germany.

The Macon: a New Class of Airship

The Macon pushed the envelope in every conceivable way. She weighed more than 200 tons, carried a complement of 83 officers and crew over a range of 7,000 miles, and could stay aloft for more than three days. Fully outfitted with a galley, three dining messes, sick bay, smoking room, and separate sleeping quarters for officers and enlisted men, the Macon was a self-contained world in the sky. She was kept aloft by nonflammable but very expensive helium gas. Her 12 helium cells were made from gelatin latex and were suspended from a complex internal skeletal structure made of a German-invented alloy called Duralumin 17-SRT. Composed of aluminum, copper, magnesium, and manganese, Duralumin was designed to be both durable and lightweight, the carbon fiber of its time.

Because of her clean lines and overpowering size, the Macon was one of the most beautiful airships ever designed. She was powered by eight German-made Maybach VL-II, 12 cylinder engines, each of which generated 560 horsepower at 1,600 rpm. The Maybachs drove an external, triple-bladed propeller that enabled the ship to reach speeds up to 75.6 knots (about 80 miles per hour), a bit faster than her sister ship, the USS Akron, which could only do 69 knots, and her props could swivel up and down as well as in reverse. At top speed, she could cross the entire United States in 37 hours.

Being a lighter-than air-ship, weight was everything for the Macon. She was actually 8,000 pounds lighter than Akron, but keeping her trim while airborne involved a complicated ballet involving fuel, water ballast, helium gas, outside temperature, and altitude, not to mention barometric and wind conditions. To compensate for the decrease in weight that naturally came from fuel consumption, the Macon recycled her engine exhaust through condenser units designed to capture water vapor necessary to maintain the ship’s trim.

The Macon had two control cars, one near the bow where the officers managed the rudder and elevator controls; monitored the altimeter, air speed, and rise-and-fall indicator; and issued commands to the eight engine rooms. A second control car located in the lower stabilizing fin at the ship’s tail was a backup in case anything happened to the primary command car. The Macon also sported a spy car or “angel basket,” which was lowered from the ship’s bottom on 3,000 feet of cable to spy on the enemy below while the dirigible stayed hidden in the clouds. The spy car sported a tail fin and rudder pedals to provide a margin of control, and could be used as a raft to retrieve downed pilots. The spy car was the bane of whoever rode in it. It was difficult to control, open to the elements, and virtually guaranteed even its most hardened occupant a severe case of airsickness. The Macon carried her own defensive armament in the form of machine-gun installations in the airship’s bow, aft, and topside that could be used to defend the airship from attacking aircraft in any direction.

“Parasite Fighters”

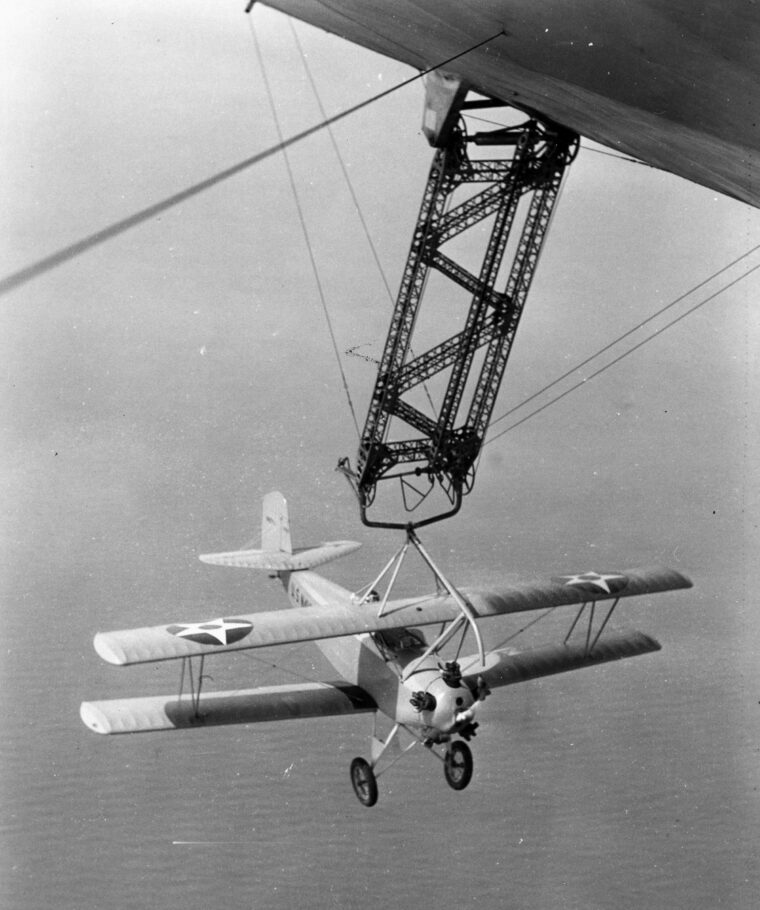

One of the Macon’s most appealing features was her ability to launch and retrieve airplanes in mid-flight. She carried five Curtiss F9C-2 Sparrowhawk fighter planes in a hangar inside her belly. The Sparrowhawks, which were known as “parasitic fighters,” hung from a rail system inside the airship and were guided from their hangar’s four respective corners to a T-shaped opening in the Macon’s belly located slightly aft of the control car. A fifth Sparrowhawk could be accommodated in the center of the hangar, but was rarely carried. When ready to be deployed, the Sparrowhawks were transferred to a crane with a harness-like trapeze attachment that lowered the aircraft through the opening without their wheels ever touching the ship. With the aircraft hanging outside but still attached to the airship via a trapeze, an electric-ignition line would be lowered to the pilot, who would connect it to his aircraft and start the engine.

Sparrowhawk pilots turned over their engines outside the airship as a safety precaution to avoid a catastrophic explosion from occurring inside the dirigible. Once the engine was running, the pilot pulled a lever outside the cockpit near the top left wing and released the plane from the trapeze to fly off under its own power.

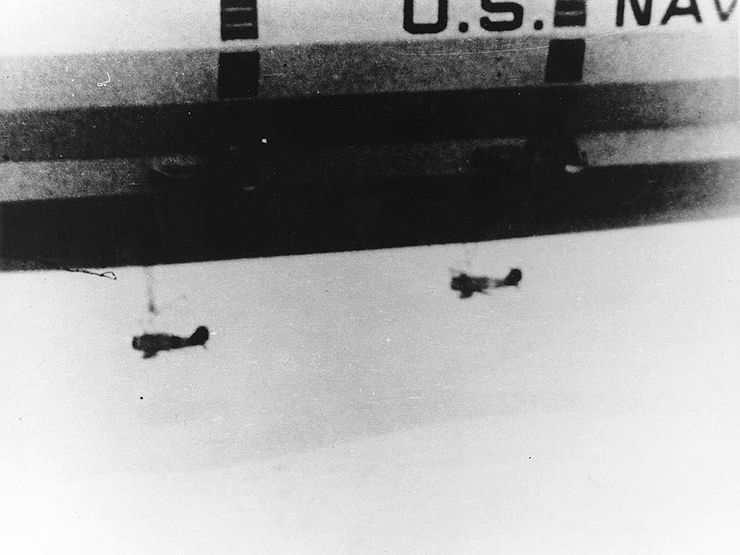

The Macon was not just a catch-and release-program, however; she also retrieved her aircraft in mid-flight. The Macon’s Sparrowhawk pilots would fly behind and underneath the airship, guided by two signal men visible from the T-shaped opening who helped them close the gap in the sometimes turbulent slipstream. Carefully maneuvering his throttle at near stall speed, a Sparrowhawk pilot inched his way upward beneath the giant dirigible until the skyhook latched into place on the trapeze catch mechanism. Then the pilot would cut the engine and the plane would be winched back on board. Another trapeze was located near the tail of the Macon, where a Sparrowhawk could “perch” while waiting its turn to come aboard. No wonder the pilots of this elite group were called “the men on the flying trapeze.” They even adopted a special insignia that depicted two trapeze artists poised to catch one another in mid-air (a fat one signifying the dirigible and a skinny one signifying a Sparrowhawk).

Because every pound on a dirigible counted, the protocol was to wait until the mother ship was airborne and then fly the aircraft on board. Neither the Akron nor the Macon took off with her full complement of fighters on board. In this way, the ship was spared lifting an additional 14,000 pounds that could make a real difference if there was no wind.

Questionable Utility in Modern War

Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, and Captain Garland Fulton were the Navy’s two most influential LTA evangelists. Both believed passionately in the strategic value of the rigid-frame airship and its ability to serve as the eyes of the fleet. The Macon and the other dirigibles were used as scouting ships to reconnoiter a larger area of ocean in search of the enemy and provide useful intelligence. They could do this faster and more cheaply than a typical destroyer, and great promise was seen in the Macon’s ability to warn the Navy of an approaching enemy in the days before radar existed. Meanwhile, the Macon’s complement of Sparrowhawks provided protection for the dirigible against enemy ships and aircraft. Although they provided some supplemental scouting, the Sparrowhawks were not the primary scouting vehicles—that was the dirigibles’ role.

The main problem with this approach was that the dirigibles kept getting “shot down” during fleet exercises. If the Macon was close enough to spot an enemy ship, she was also vulnerable to attack. Nevertheless, during 1934 fleet exercises in the Caribbean, the Macon’s performance was judged successful enough that she was ordered west to participate in Pacific Fleet war games, although some Navy higher-ups, including Admiral William H. Standley, chief of Naval Operations, still strongly questioned her usefulness.

Wiley’s Proof of Concept

Over time, it became obvious that airships were vulnerable to carrier-based planes as well anti-aircraft fire from surface ships. As a result, by 1934 the Macon was struggling to find an effective role while an increasingly heated debate raged inside the Navy and the federal government over the long-term effectiveness of rigid-frame airships. To the LTA program’s credit, a good deal of flexibility, innovation, and learning was applied toward maximizing the Macon’s strategic effectiveness. As a result, Macon’s commanding officer, Lt. Cmdr. Herbert V. Wiley, came to believe that the Macon had to evolve from a long-range scouting vehicle to a floating platform, or aircraft carrier, with the Sparrowhawks taking over as the principal scouts. Wiley felt that the Sparrowhawks could significantly extend the dirigible’s range and more quickly cover a broader area while the dirigible remained safely hidden in the clouds.

By July 1934, Wiley was ready to prove his point and decided on an audacious move to secretly find and rendezvous at sea with the USS Houston, which was carrying President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his secretary of the Navy, Claude A. Swanson, from Central America to Hawaii. Wiley successfully located his “prey” despite the ship’s position being top secret and sent out two Sparrowhawks to drop packages for the president containing mail and newspapers onto the ship’s deck. The pilots missed their target—probably just as well, considering that FDR was situated somewhere directly below—and the packages had to be fished out of the ocean. But the president was suitably impressed to be located 1,500 miles out to sea, and it seemed for a time that the Macon’s stock was rising. Wiley’s superiors were less impressed, accusing him of “misapplied initiative” and threatening him with court martial for his reckless actions.

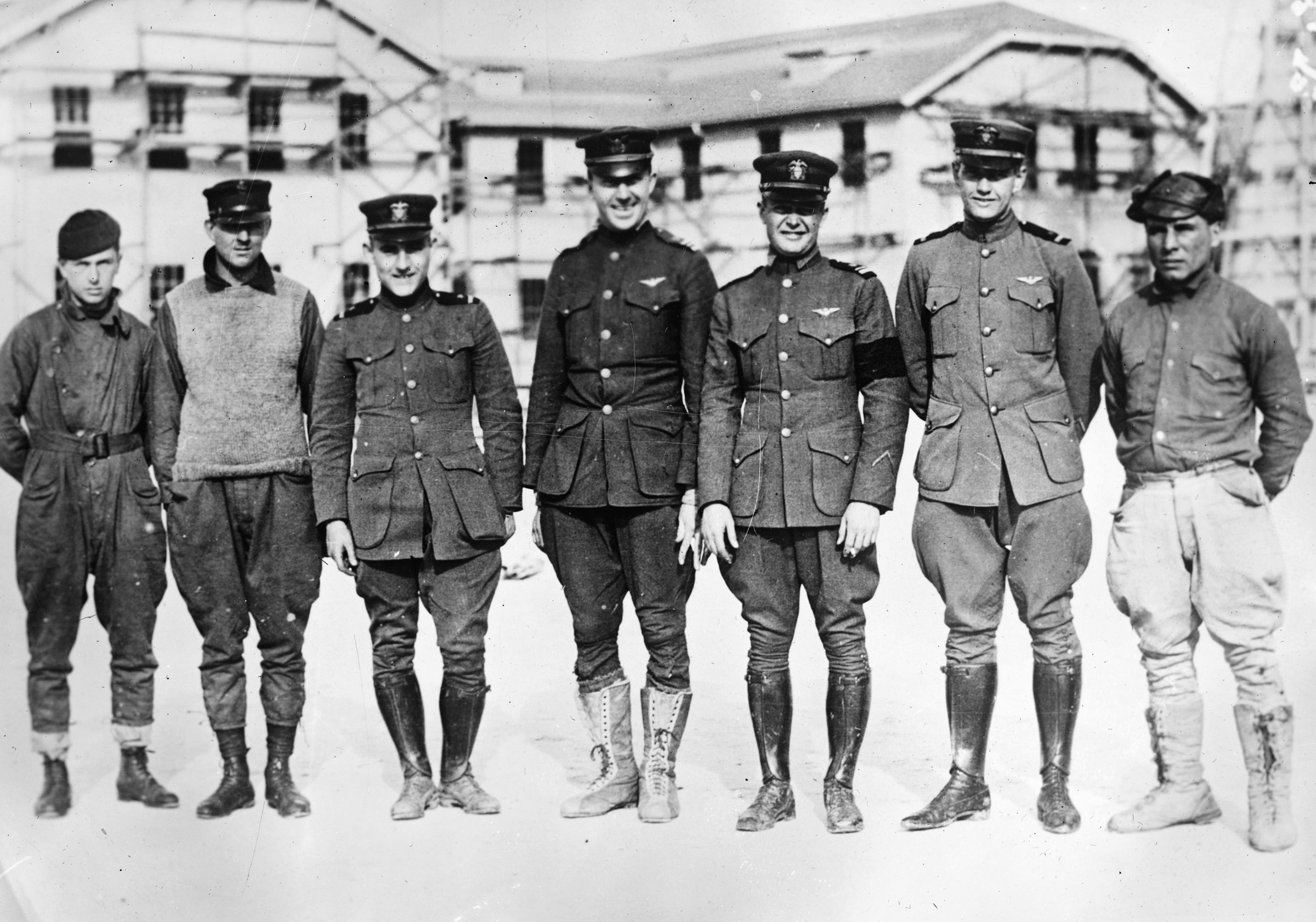

The LTA Program Crashes

The LTA program faced greater problems than one eager commander’s desire to prove the strategic effectiveness of his command. The first dirigible, the USS Shenandoah, broke up spectacularly over the Ohio Valley in 1925, killing 14 crew members. Eight years later, on April 4, 1933, the USS Akron ran into severe weather off the New Jersey coast and sank tail-first into the Atlantic Ocean. Wiley, who was an officer on board at the time, was one of only three crewmen to survive the crash; 73 others died, including Admiral Moffett, the father of naval aviation, and two other crewmen from a Navy J-3 blimp which had joined the search for survivors.

The Macon remained a familiar sight inside her massive hangar at Moffett Air Field in Sunnyvale, California, a few miles from the Stanford University campus. On February 11, 1935, she left the air field to reconnoiter with the Pacific Fleet in southern California. Eager to get under way, Macon’s engineers had not yet completed reinforcing her vertical tail fin and supporting structure, which had been damaged on a previous mission over Texas.

The next afternoon, off the coast of Big Sur, the ship ran into a powerful gust of wind, which triggered a structural failure causing the top stabilizing fin to sheer free, sending metal shards into her three rear gas cells and dropping the Macon tail-first into the Pacific. It was a virtual reprise of the Akron’s fate. Once again, Wiley’s luck held out. Only two of his 83 crewmen died in the slow-motion crash—Radioman 1st Class Ernest Dailey, who jumped out of the ship 100 feet above the ocean, and Filipino mess steward Florentino Edquiba, who refused to abandon ship because he could not swim. Survivors were picked up by the USS Richmond and USS Concord within an hour.

The third spectacular crash in 10 years marked an end to the LTA program of building rigid airships. President Roosevelt appointed a private commission to look into the mishaps, and although the commission, chaired by Stanford engineering professor William F. Durand, recommended that the program be continued, neither the Navy nor the government had the stomach to construct any more rigid-body airships. The Navy continued building blimps and semi-rigids until 1962, but the giant dirigibles were doomed because of uncertain strategic benefits, a mixed track record of effectiveness, and radically changing technology—not to mention a Congress that was hard-pressed to justify spending more money on accident-prone aircraft during the Depression. By May 1935, the dirigibles—beautiful as they had been to look at—were an obsolete branch of America’s aviation tree.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments