By Roy Morris Jr.

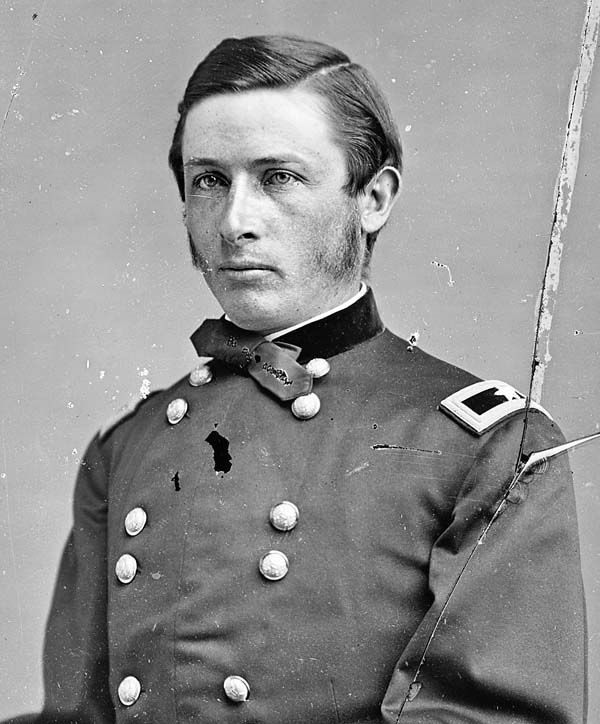

The young captain of engineers who discovered the dangerous bulge in the “Mule Shoe” salient at Spotsylvania, Ranald Slidell Mackenzie, would go on to make a name for himself during the Civil War and the subsequent Indian campaigns out West. Indeed, no less a judge than Ulysses S. Grant considered Mackenzie “the most promising young officer in the Union Army.” Had it not been for suddenly encroaching mental illness, Mackenzie might well have become commanding general of the U.S. Army. Instead, he was destined to live out the final years of his life in complete obscurity, far from the blazing battlefields of his youth.

Mackenzie, who came from a prominent New York family, attended Williams College before entering the United States Military Academy at West Point. He graduated first in his class in June 1862 and was commissioned a lieutenant in the engineering corps. At the Second Battle of Manassas that August, he suffered the first of several serious wounds when he was hit in the shoulder by a .52-caliber musket ball.

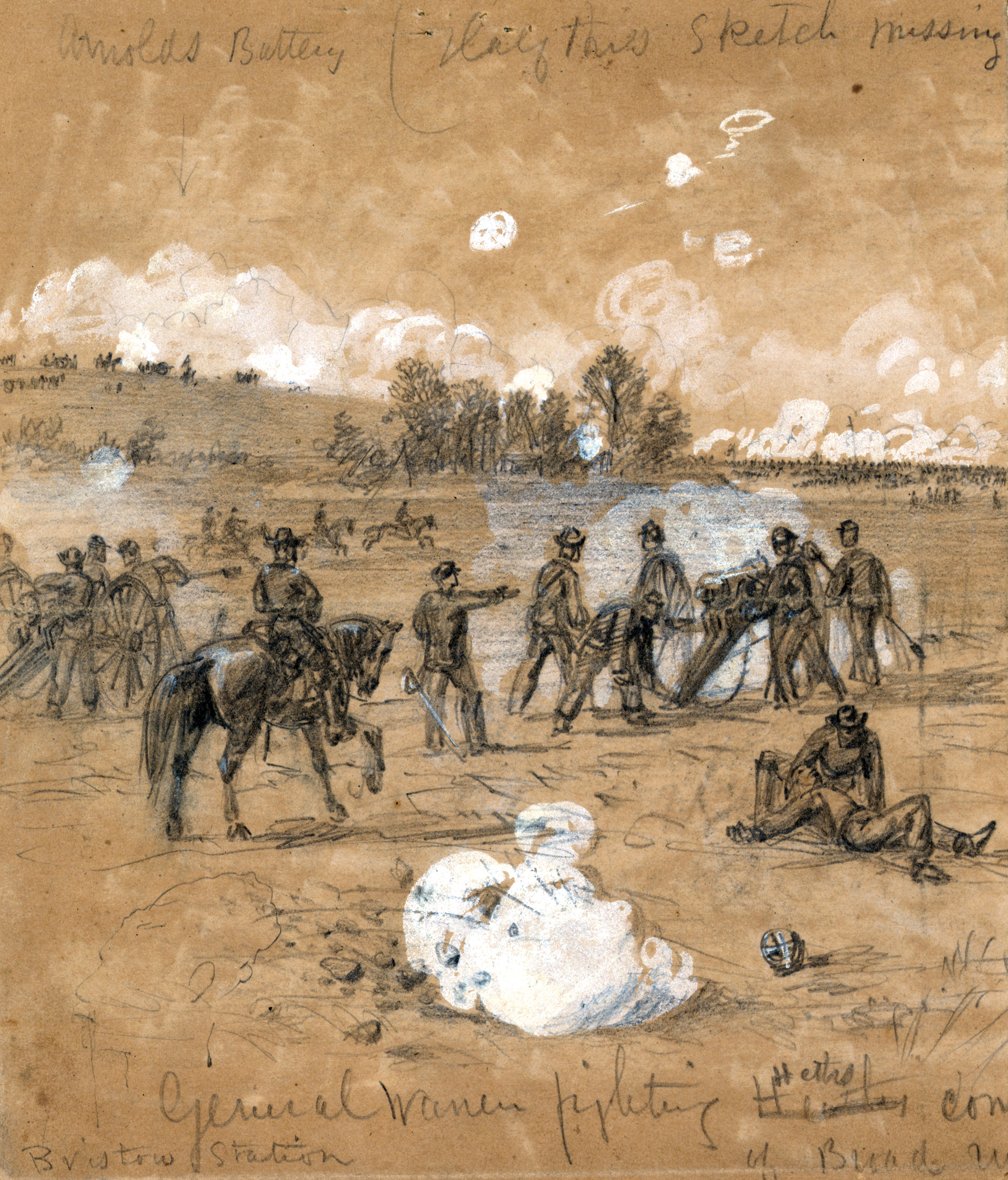

Subsequently, Mackenzie saw action in most of the major battles in the eastern theater of the war. Promotions and wounds seemed to follow him wherever he went. In all, he was wounded six times in the war, losing two fingers to a Confederate bullet at Petersburg and once becoming temporarily paralyzed when he was struck in the chest by a spent artillery shell. Along the way, he was commended seven times for gallantry and became at age 24 the youngest brevet brigadier general in the Regular Army and the youngest major general of volunteers one year later.

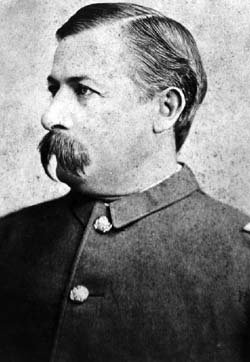

Following the Civil War, Mackenzie went out West, where he served under his old Civil War mentor, Phil Sheridan. His relentless tactics and tireless campaigning won him the admiring nickname “Bad Hand” from his opponents—both for his missing fingers and his uncanny ability to capture his foes. Mackenzie decisively defeated the Comanches in Texas in 1872, then crossed the Mexican border to destroy Kickapoo raiders on the far side of the Rio Grande. A year later, he inflected a major defeat on Kiowa, Comanche and Cheyenne warriors at Palo Duro Canyon during the Red River War.

In the aftermath of the Custer massacre at the Little Bighorn in 1876, Mackenzie led a retaliatory raid against Chiefs Dull Knife, Yellow Nose, and Little Wolf, destroying the Northern Cheyenne power base in the Powder River Valley and capturing Sioux chief Red Cloud. He subsequently defeated rebellious Utes and Arizona Apaches, becoming at age 42 the youngest brigadier in the Regular Army.

But Mackenzie’s victories came at great pain to himself. He continued his seemingly unbreakable habit of getting wounded, being shot in the leg by a Comanche arrow and thrown from a wagon onto his head and knocked unconscious. By the time he was given command of the Department of Texas in late November 1883, he was already showing signs of mental and emotional deterioration, possibly the result of tertiary syphilis. After being beaten savagely during a drunken melee in a San Antonio saloon, Mackenzie was found lashed to a wagon wheel in a seamy alley. The post physician declared him unfit for duty and recommended that he be confined in an insane asylum.

Mackenzie returned to the East in the company of his sister, obeying bogus orders from Sheridan to go to Washington and reorganize the Army. He was admitted to Bloomingdale Asylum in New York City and judged “totally unfit for military service.” The Army granted him a full pension. The once-brilliant young soldier spent the last five years of his life in and out of mental institutions before dying in January 1889. He was buried on the grounds at West Point, where a tall stone obelisk at the northeastern edge of the academy cemetery marks the final resting place of one of the school’s most promising—and unlucky—soldiers.

Fascinating subject matter with too few details. Also, additional reference materials would be helpful for follow-on reading. Please consider for all of your on-line articles.

Really appreciate the wide diversity of subject matter. Keep up the great work.

Chris

An excellent book which I am just now finishing is “Empire of the Summer Moon” which chronicles the frontier fight with the Comanche, et al. Mackenzie should not be forgotten. His was a life of war from the Civil War, to the Frontier War with the Comanche, et al, to the end with his personal war with mental illness. I suspect his descent into mental illness is the reason history forgot him. We still don’t understand it.

I too am currently reading Empire of the Summer Moon. R S Mackenzie seems to me to be just as fascinating as Quannah Parker. I can’t find very much information about the man though, certainly not from here in the U.K.

Read “The Capture”

McKenzies campaign against the Comanches

I am reading Empire of the Summer Moon by SC Gwynne. A thoroughly good read. It gives a great insight into Mackenzie’s career. A fascinating personality, almost as noteworthy as that of Quanah Parker himself.

Andrejs

Empire of the Summer Moon author SC Gwynne disputes the idea that General Mackenzie’s mental illness was caused by syphilis. The book suggests that several other factors contributed to his mental decline, including suffering sunstroke as a child, the effect of years of pain due to his six major injuries in battles, post traumatic stress, and the bad head injury he received after being thrown from a wagon late in his life. He was said to have been in a stupor for three days following this injury, and shortly afterward began displaying the anger and bad temper which portrayed mental illness. Perhaps he had a severe concussion, and never recovered. He was a fascinating character, and his performance in battles and as an officer is amazing. Empire of the Summer Moon is an excellent read, very informative, and full of anecdotes about the wild and dangerous days of western expansion.