By Robert P. Watson, Ph.D.

News arrived in the capital city that the British army had defeated a hastily-gathered and rag-tag collection of American soldiers, sailors, militiamen, and government clerks in Maryland at Bladensburg. Rumors ran wild about what Gen. Robert Ross and Adm. George Cockburn would do next. They were now just a short march from Washington. Nothing stood in their way. It was Wednesday, August 24, 1814, and inside the Washington Navy Yard, Capt. Thomas Tingey and his clerk, Mordecai Booth, were forced to face the unspeakable—would they have to burn the important naval facility to prevent it from falling into British hands?

Booth had spent the preceding two days either frantically preparing supplies to be transported out of the Navy Yard or on horseback riding around the region trying to gather intelligence about both British intentions and the haphazard American defenses. An unlikely hero, the unimposing 51-year-old clerk had no military training. He had just been appointed clerk at the Navy Yard in 1811, a year before war broke out. But during this critical moment, he was one of the few who chose to stay at his post.

Upon hearing of the defeat at Bladensburg, Booth again rode to nearby hills to surveil the countryside. There was good news and bad—on the one hand, there was no sign of the British army. As he noted, “I saw not the Appearance of an Englishman” on the road to Washington, which inspired hope that they were still in Maryland and maybe planning to march on Baltimore or another target. On the other hand, there were still no defenses in and around Washington. Everywhere Booth rode, he saw panic and chaos. American militia units were retreating in every direction and the remaining residents of the capital city were fleeing from their homes. In a hurried but thorough note, he shared both assessment of the situation and his despondence with Capt. Thomas Tingey, commandant of the Navy Yard, writing “but Oh! My Country—And I blush Sir! To tell you—I saw the Commons Covered with the fugitive Soldiery of our Army—runing, hobling, Creaping, & appearently pannick struck.”

Booth stopped and questioned some of the militiamen, but none had any plan except to flee. The clerk rushed back to the Navy Yard, hoping Tingey had better news. It was wishful thinking. Tingey had not received orders one way or the other—which was interpreted by the two men as the worst-case scenario.

Remounting his horse, Booth raced into the city to see if the army had regrouped and were digging in to defend it. What he saw was just as bad and ended any hope of saving the capital or the Navy Yard. There were only about 250 troops in the city—what was left of Commodore Joshua Barney’s brave sailors, about the only unit that put up a stingy defense at Bladensburg. Unlike the U.S. army and militia units who fled in disarray, Barney’s men had rushed to the capital hoping to find other units in order to organize a last-ditch stand. After watching the remaining residents and soldiers run, however, they seized the four ornamental cannons in front of the Capitol Building and a small 6-pounder sitting beside the Executive Mansion. Finding only two horses and two wagons, they loaded two of the guns and the small cannon then spiked the other two and abandoned the city. It was nearing sunset and they constituted the last vestige of the American military in the capital.

Booth rushed back to the Navy Yard to inform Tingey that the military had not regrouped to defend the capital. The Madison administration had proven inept and, shockingly, had made no contingency plans despite the fact that a flotilla of British warships had been prowling the Chesapeake for weeks and a large British force was spotted disembarking along Maryland’s eastern shore.

As he rode, Booth heard an enormous explosion, but discovered it was a nearby bridge being destroyed and not the Navy Yard. Upon arrival however, the clerk learned from Tingey that an aide to the Secretary of the Navy had just delivered a similarly distressing report—the army was scattered and there was no defense of the region. They had no recourse. It was time to burn the Navy Yard.

Burning the shipyards, however, came with the risk that the massive fire might spread out of control to the surrounding homes, as the wind was beginning to pick up. The few remaining residents begged the commandant not to set the fire. Tingey was in an impossible situation. He was also still recovering emotionally from having recently lost his wife and the prospect of destroying the facility he had built and devoted the past 14 years to weighed heavily on his heart. With much sorrow, Tingey informed the residents to evacuate. It was nearing 5 p.m. and he was out of options.

Booth begged his superior for permission to yet again ride out—one last time—on another dangerous scouting mission to try to find the whereabouts of the British. He reasoned that they still had perhaps two or three hours and a fleeting chance that the enemy was headed to Baltimore. The two men agreed that if Booth did not return in time, Tingey would start burning the facility. Exhausted and full of anxiety, Booth raced back out to gather intelligence, hoping for a miracle. He encountered a butcher from Georgetown named Thomas Miller who had also been looking for either army. Booth asked to join him and both men rode to where Miller had last seen the enemy. It was not good. A long red line was on the march on the main road into Washington.

Booth rode back into the capital, stopping at the President’s House, wondering if Madison and his wife were still there or if they or any members of the Cabinet might have orders as to what should be done. As he arrived at the mansion, so did a colonel, who dismounted and hurried to the front door. Booth watched as the officer yanked on the heavy bell rope. Nothing. He yanked repeatedly and banged on the door. Still nothing. The officer hollered, “French John!” There was no answer from Jean Pierre Siousat, the steward. The home was empty; the president, first lady, their staff, and the 100 soldiers assigned to protect Mrs. Madison were gone. “All was as silent as a church,” remembered Booth. The clerk, who had been riding and working for three days straight, finally paused, exhausted, and pondered the alarming reality of what was happening. It hit him “that the metropolis of our country was abandoned to its horrid fate.”

The British army was about to arrive, plunder, burn, or perhaps occupy the city he loved. Booth remounted and rode back to the Navy Yard. He had one more dreadful job to do that day. The clerk was struggling with his own issues. His wife, a widow who brought six children into the marriage, had died just months before the start of the war and Booth was deeply in debt trying to care for a large family.

On the way back to the Navy Yard, Booth encountered a small party of American officers on horseback. They conferred and rode together. However, near Long’s Hotel they were surprised by an advance unit of British soldiers who tried to capture them. Booth was nearly shot. The Americans managed to elude them, but Booth began to worry that he had been away too long, that Tingey and the Navy Yard may have been captured. He pushed his horse, now barely able to walk, on the precarious ride back toward the wharf.

Tingey was also worried. Had something happened to Booth? They were out of time. Tingey sent the few remaining naval staff away and saw to it that his clerk’s children were evacuated. The commandant planned that, if he did not hear from Booth by 8:30 p.m., he would burn the Navy Yard. But his trustworthy clerk arrived 30 minutes before the deadline and delivered more crushing news.

They had no choice. Tingey did not wait until 8:30; he gave the order as soon as Booth arrived. The magnificent Navy Yard, designed by the famed architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, who had helped build the Capitol, was burned. The men watched the sickening scene as the new 44-gun frigate USS Columbia, scheduled to be launched in only a few days, the 22-gun sloop USS Argus, the new schooner USS Lynx, and other ships were engulfed in flames. Stockpiles of wood and supplies from the storehouses, the sawmill, ropewalk, and the enormous dry dock burned bright. The winds blew the flames throughout the massive complex, and the fire was soon a raging inferno.

Tingey and Booth said their goodbyes. The commandant departed in a small boat for Alexandria; his clerk waited a few moments longer, staring at the growing flames. At 8:20 p.m., he mounted his horse for the final time. The animal could no longer run, but the clerk could not abandon his reliable steed, noting that he was “too good a one to be lost.” As Booth rode slowly out of town, he turned and saw the bright glow of the fires behind him. Crossing a bridge he heard a cascade of explosions from the docks, which he knew was the powder and munitions. Overcome with emotion, Booth described the moment as “So repugnant to my feelings, so dishonorable, so degrading… so awful.”

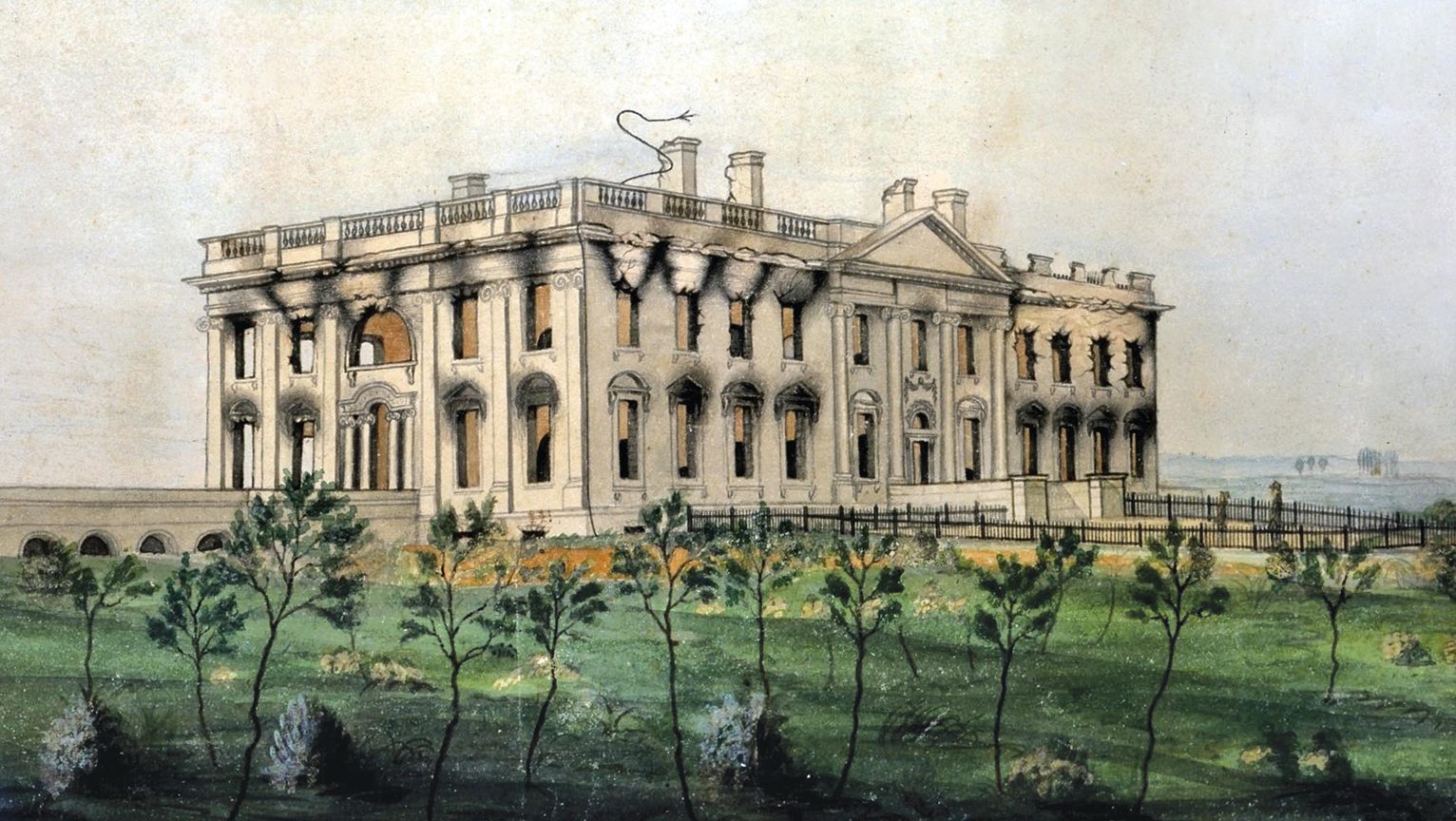

Later that night, the British entered the city. They would burn the Capitol, President’s House, and government buildings such as the War Department, State Department, and Treasury. It was observed by Booth, who had spent the night and next day watching the destruction. He was stunned. Never had he seen or imagined such an enormous fire. Booth was particularly struck by the sight of the largest building in the country burning, bemoaning that the Capitol will “be an Additional Monument of our Country’s disgrace and dishonor.” His closed his report with the words, “This all will agree in—that the Stain can never be blotted from the recollection of Americans.”

A month later, Tingey wrote to his daughter, recording “I was the last officer who quitted the city after the enemy had possession of it… I was also the first who returned.” The warship USS Tingey would later be named in his honor as would the gate at the Navy Yard.

One year after the conflagration, Booth’s own home was damaged by fire. He and his family continued to struggle. Booth essentially oversaw the rebuilding and supervision of the new Navy Yard as Tingey’s health deteriorated in the years to come. In 1819 and 1820, Tingey submitted requests that the hardworking clerk from Virginia be given an assistant and a pay raise. Both were declined. Booth died in 1831 and was buried in the congressional cemetery near Tingey.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments