By Flint Whitlock

Britain badly needed a victory. As if to underline Britain’s difficult fortunes, on May 21, 1941, the German battleship Bismarck and heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen dealt the island kingdom a serious blow by sinking the battlecruiser HMS Hood and severely damaging the new battleship HMS Prince of Wales during a furious engagement in the Denmark Strait. While the naval clash had been a German victory, it left Bismarck badly damaged and caused her captain, Kapitän zur See Ernst Lindemann, to sail for St. Nazaire, France, and the repair docks there.

The Atlantic port of St. Nazaire is perhaps best remembered for its heavily defended submarine pens, but it was most famous before the war as having the world’s largest dry dock and repair facilities. In fact, its largest dock was known as the Normandie Dock because that is where the world’s largest passenger liner, the Normandie, docked between cruises.

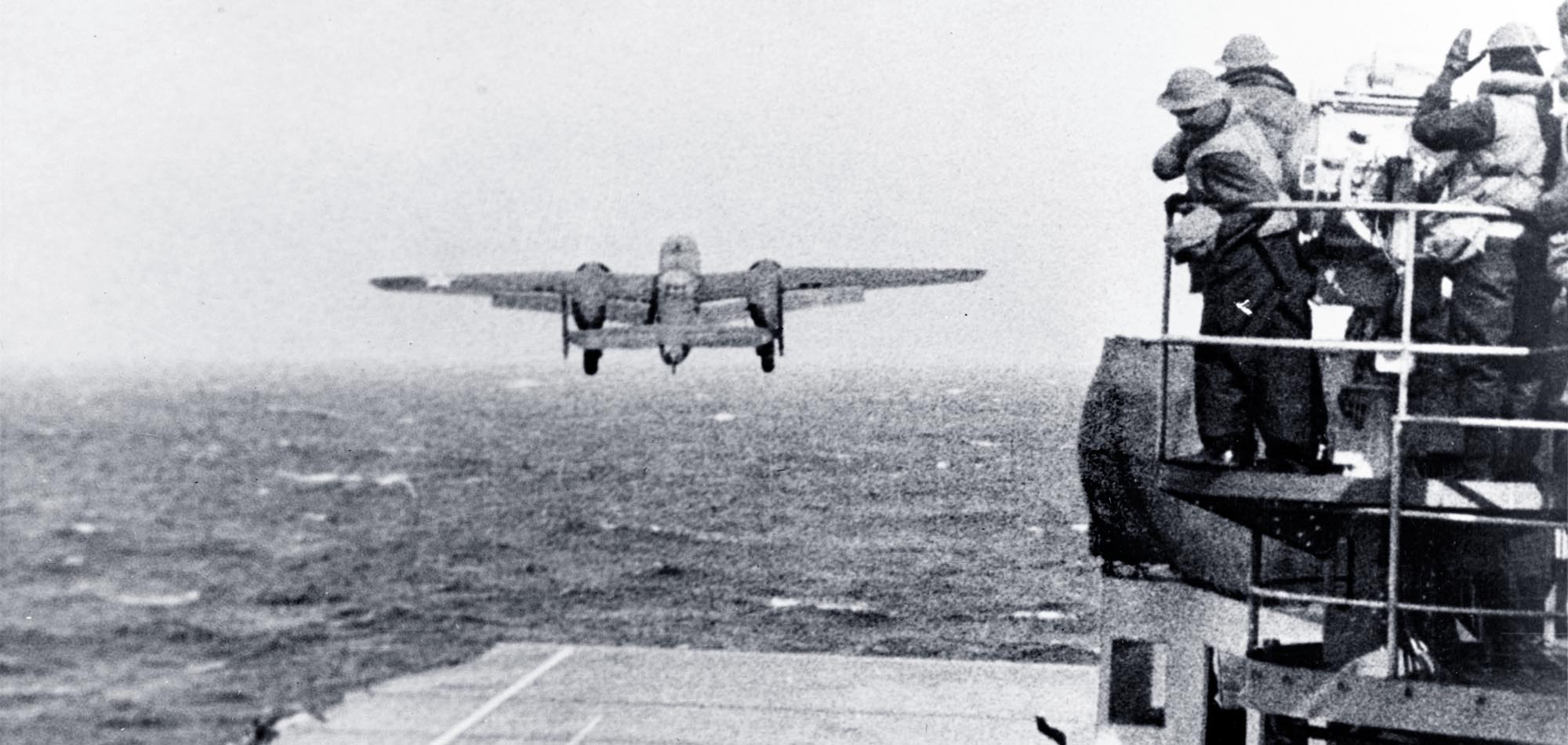

But Bismarck never arrived at St. Nazaire. Launched on February 14, 1939, for the anticipated purpose of controlling the seas, the 50,000-ton battleship was attacked on the morning of May 27, 1941, by warplanes from the British aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal. Aerial torpedoes jammed her rudder and left her vulnerable to a pummeling by the British fleet that included the battleships HMS Rodney and King George V, plus numerous destroyers and cruisers.

Preventing the Next Bismarck

By 10 am, Bismarck’s guns had gone silent and she slipped beneath the waves in 15,700 feet of water about 300 nautical miles west of Ushant, France. Of Bismarck’s crew of 2,200, a total of 1,995 perished. Worried that Bismarck’s larger and even more powerful sister ship, Tirpitz, which was holed up in a Norwegian fjord, might someday reach St. Nazaire and use that port as a base for raiding Atlantic shipping, the British Admiralty, upon Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s urging, decided that the facilities at St. Nazaire must be put out of action. If the port’s repair facilities could be destroyed or seriously damaged, the Admiralty believed that Tirpitz would never venture out of her protective fjord.

Churchill was foresquare behind such an action. He knew he needed a major, spectacular victory to revive his nation’s flagging spirits, and so he decided to rescind his previously announced ban on “silly fiascos” and mount a daring commando raid against one of the toughest targets in all of Nazi-controlled Europe: St. Nazaire’s heavily defended Normandie Dock.

At first, it was thought that an air raid by the Royal Air Force (RAF) could render the port inoperable, but that plan was scrapped. Not only was St. Nazaire protected by a formidable ring of antiaircraft weapons that had made a handful of previous raids ineffective, but a large civilian population lived in the nearby town and the British were reluctant to risk their lives in a raid that might prove to be less than precise. Another way would have to be found.

A sea-borne commando raid was then considered, but it, too, was seen as a high-risk operation––this time for the attackers. As Ken Ford, author of a history of the St. Nazaire raid writes, the port “is located five miles up the treacherous estuary of the River Loire and is only approachable from the sea by a single narrow channel, which, in 1942, was covered by several batteries of coast defense guns.”

But, in January 1942, Churchill gave Lord Louis Mountbatten, the British Chief of Combined Operations, the task of devising a plan to destroy the facilities. The plan that Mountbatten and his team conceived was brilliant but would rely on the steadfast courage and nerves of the men who would be asked to carry it out.

“Full of Imponderables… Hazardous in the Extreme”

It was decided to use an old British destroyer, modify it to look like a German warship, and pack it with commandos and explosives with a time-delay fuse, then ram the dry dock’s outer gates during the dead of night. The commandos would pour out of the ship and onto the docks to gun down German sentries and blow up the vital port facilities.

This would be timed with an RAF raid to further create havoc and confuse the defenders. Before the Germans knew what hit them, the commandos, their mission accomplished, would be picked up by motor launches and returned to safety. Later, when the Germans would be going over the rammed ship and inspecting the damage to the lock, the time-delay fuse would detonate the explosives for maximum impact and casualties. As author Ford says, “The plan was full of imponderables and was hazardous in the extreme.”

The scheme was initially met by the Admiralty with skepticism and negativity, but Mountbatten and his men were undeterred; they reworked the details and re-presented the plan, dubbed Operation Chariot. On March 3, Chariot was approved.

An obsolete British destroyer, HMS Campbeltown (which was formerly the USS Buchanan, given to the British in the Lend-Lease program) was selected to star in this drama. Commander Robert E.D. “Red” Ryder, 34, was put in charge of the Royal Navy’s role in the operation. Ryder had already had a long naval career with service in submarines, an arctic exploration, and a stint as the commander of a frigate. It would be his job to transport the Campbeltown and accompanying flotilla of motor launches, similar in size and appearance to American PT boats, the 450 miles to St. Nazaire and to withdraw any surviving commandos back to Britain, all the while fighting off the expected German counterattack.

Preparing for the Raid

On March 10, 1942, Campbeltown sailed for Devonport to be superficially disguised as an enemy warship. Two of her four funnels were removed, and the remaining two were shortened and cut at an angle to resemble a German Möwe-class destroyer. Extra armor plating and armament was added in the event the Germans “smelled a rat” and took the ship under fire. Commanding the fake German ship would be a seasoned British officer, Lieutenant Commander Stephen H. “Sam” Beattie.

To provide enough explosive power to destroy the target, 24 Mark VII depth charges, each filled with 400 pounds of explosives, were loaded into a steel tank installed in the ship’s forward compartments, then sealed behind a wall of concrete. Pencil fuses with an eight-hour delay were inserted into the charges and would be primed by naval Lieutenant Nigel Tibbits just before the ship rammed the lock. Once activated, the acid in the fuses would dissolve the copper restraining wire, causing the detonators to explode the depth charges.

Meanwhile, a contingent of British commandos would undergo intense training for the mission. In early 1942, there existed the Special Service Brigade made up of a dozen 500-man commando units, all volunteers. From this group of about 6,000 men, more than 200 of the toughest were chosen for Operation Chariot.

Lieutenant Colonel Augustus Charles Newman, head of Number 2 Commando, was selected to command the ground forces. Newman was a building contractor by profession and had served in the Essex Regiment of the Territorial Army before the war. At 38, he was considerably older than most of his subordinates, but his leadership ability and the way he related to his men meant that he was popular and well respected.

Of primary importance was training in demolition procedures specifically tailored for the St. Nazaire operation. An expert in dockyard demolition, Bill Pritchard, a captain in the Royal Engineers, was recruited as the instructor. Classes were carried out at the Cardiff (Wales) and Southhampton docks on equipment similar to what the commandos were likely to encounter.

Although the teams did not use actual demolitions or live ammunition, their training was highly realistic. After learning as much as possible about the technical workings of locks, pumps, cranes, electrical equipment, and power stations, they were required to correctly place their dummy charges in the dark and often with only a few of their mates present––the others being considered casualties.

While half the force was being turned into explosives experts, the other half underwent strenuous training in the techniques of nighttime street fighting; they would act as the protection squads for the demo men and aid in the force fighting its way out of the port.

In addition to honing their combat skills and becoming demolitions experts, the commandos spent untold time going over a detailed model of the port and continually rehearsing their assignments. No detail was left to chance, for the raid relied on split-second timing; if one element was delayed or failed, the entire mission would be placed in jeopardy.

The Plan of Attack: Entering the Port

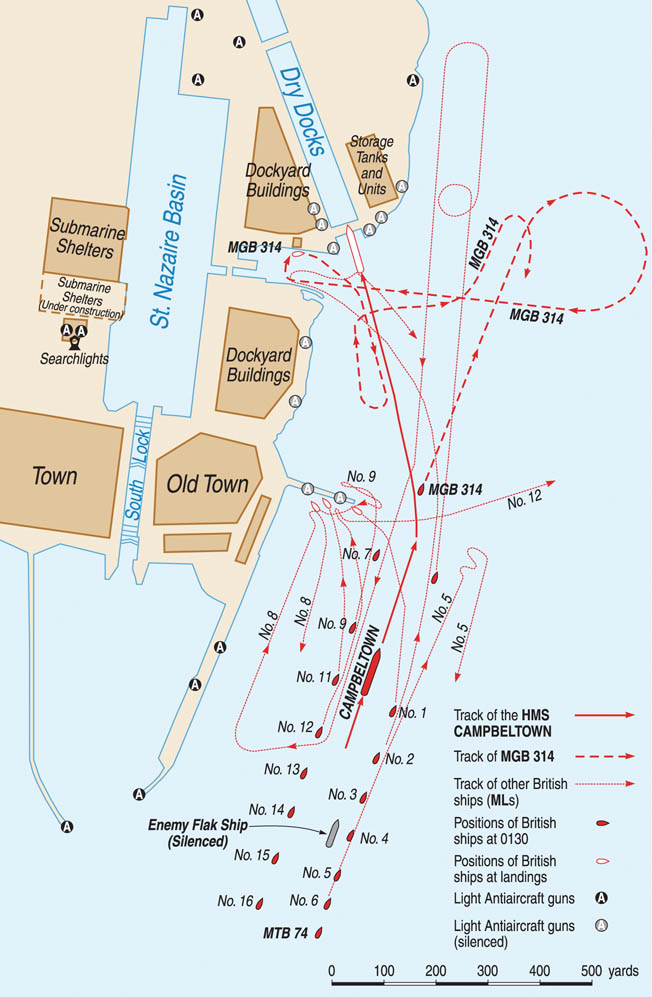

Here is how the whole scenario was supposed to come together: The Campbeltown, in its disguise as a German ship, and a flotilla of 18 motor launches, motor gun boats, and motor torpedo boats filled with commandos, would be accompanied to St. Nazaire by two Royal Navy destroyers, Tynedale and Atherstone. At about midnight of D-Day, in late March, the Royal Air Force, flying from British bases, would bomb the port, diverting the defenders’ attention and causing them to seek shelter. Simultaneously, the Campbeltown would enter the mouth of the Loire and swiftly move the six miles toward the port.

To assure that they could find the Loire in the dark, a submerged British submarine, Sturgeon, would position itself there as a navigational beacon. As the flotilla reached the river’s entrance, the two destroyers would drop off and the force would adopt battle formation, with gunboat MGB-314 and its radar and echo sounder in the lead, guiding the force across the mudflats and shallows.

Flanking MGB-314 would be the motor torpedo boats ML-160 and ML-270, ready to fire their torpedoes at any vessel threatening the force. After that would come Campbeltown, trailed by two columns of motor launches on either side and to the rear. The port column would land its commandos at a lighthouse-crowned stone pier called the Old Mole, where a set of stone steps led down to the water; the starboard column would head for the Old Entrance nearby.

Three more motor launches, MTB-74, ML-446, and ML-298, would cover the rear of the column. MTB-74 would also keep station at the rear and, if ordered, would torpedo the small lock at the Old Entrance that led into the submarine basin. Two pillboxes located near the Old Mole would be attacked by teams of commandos landed by six boats: ML-192, ML-306, ML-307, ML-443, ML-447, and ML-457. Most of the rest of the motor launches would then patrol up the Loire to engage shore targets and reduce the enemy’s ability to concentrate his fire on the commandos.

While the commandos were coming ashore to wreak havoc and confusion, the raid’s major act would take place. The Campbeltown would dash at full speed toward the southern lock gate of the Normandie Dock and ram the steel structure. The time fuse would set off the hidden cache of 9,600 pounds of explosive hours later.

The Plan of Attack: Three Commando Groups

Colonel Newman’s commandos were organized into three groups with three separate missions. The first group of six teams would disembark from its motor launches on the north side of the Old Mole jetty and lighthouse, then spread south along the East Jetty and onto the docks, where it would knock out the power station and destroy the gun positions, lock gates, swing bridges, and lifting bridges that led into the submarine basin.

The second group of five teams would land at the Old Entrance, fan out north and south, destroying swing bridges, lifting bridges, flak towers, and gun positions as they went.

The third group, made up of seven commando assault teams and two protection squads from the Campbeltown, under Newman’s second in command, Major Bill Copland, would spread out across the northeast section of the dockyard and destroy the pumping house, both the northern and southern winding sheds, and the northern and southern caissons.

One of the seven Campbeltown teams, under Captain Donald W. Roy, would head west and secure the rendezvous site at the Old Entrance/Old Mole, where Colonel Newman, brought to shore by MGB-314, would set up his temporary headquarters. Roy’s men were to seize a bridge by the Old Entrance and keep it open for the rest of the raiders as they made their way back to the evacuation site, then blow it so that the Germans could not follow.

Another of the Campbeltown teams, led by Lieutenant Christopher Smalley, would destroy the southern winding shed which controlled the mechanism that opened and closed the southern lock gates, while Lieutenant Stuart Chant and his team would enter the pumping house and blow up the impeller pumps 40 feet below ground. Such an action would make it impossible to drain water from the dry dock.

Three other teams, under the command of Lieutenants Corran Purdon, Robert J.G. Burtinshaw, and Gerard Brett, also coming from the Campbeltown, had the farthest to travel. After exiting the ship, they would move along the dock to the northern winding shed and caisson where they would destroy them and thus render the northern lock gates inoperable.

Another team, under Lieutenant John Roderick, was assigned to knock out three gun positions between the Normandie Dock and the river, then set fire to the underground fuel storage tanks. Once all the operations had been carried out, all the teams were to reassemble at the Old Entrance/Old Mole for evacuation.

Protecting the Campbeltown commandos with suppressing fire from their deck guns against shore targets would be three of the motor launches, ML-160, ML-270, and MGB-314. The motor launches would then pull back and wait in the river until the demolition tasks had been completed before moving in to shore to take on the commandos and the crew of Campbeltown. The fact that all of these actions were to be undertaken right in the midst of the well-armed German garrison made Operation Chariot not only dangerous and daring in the extreme, but suicidal as well.

All this careful planning and training rested on several wildly optimistic assumptions: that enemy opposition would be light or nonexistent; that the objectives would be identical or similar to the facilities on which the commandos had been practicing; and that, once the firing started, everything would go as rehearsed.

Operation Chariot Begins

With training completed, the Operation Chariot force of three destroyers and 18 motor launches left Falmouth Harbour, near England’s southwest tip, at 2 pm on March 26, 1942, for the open-ocean voyage of over 400 miles.

The ships and boats sailed a diversionary course to make any enemy ship or aircraft believe the group might be headed to Gibraltar or perhaps La Rochelle, farther south of St. Nazaire. A U-boat, the U-593, did indeed spot the group at 7 am on March 27 and radioed its position to headquarters but made no effort to intercept it. The flotilla, however, fired at the sub and caused it to submerge, then dropped depth charges on it.

Shortly thereafter, a group of French fishing boats was encountered. Commander Ryder sent Atherstone and Tynedale to investigate, for it was known that the Germans sometimes placed observers on French fishing vessels to spy on Allied shipping. No German observers were found, but the crews of two of the trawlers were taken aboard the destroyers, which then proceeded to sink the unarmed boats.

At 10 pm that night, the lead boat of the flotilla spotted the submarine Sturgeon’s light, and Ryder and Newman knew they were exactly in the right spot. All the vessels cut their engines and began bobbing off the coast of France, waiting for the opening act to begin.

At about midnight, the Germans at St. Nazaire heard the low rumbling of a large formation of bombers growing ever louder. The air raid alarm was sounded. Soon came the whistling noise of bombs plunging downward, and the night lit up with the flashes of explosions.

Below decks aboard the Campbeltown, with its German Navy ensign fluttering at the aft end, Lieutenant Tibbitts activated the time-delay fuse that was connected to the 9,600 pounds of explosives, and the flotilla began moving cautiously forward into the Loire. Tension was building. The destroyer and accompanying motor launches slowly passed the radar station at Le Croisic without drawing any reaction.

The Germans Uncover the Ruse

It was now 30 minutes past midnight on May 28, and luck was riding with the raiders. The flotilla quietly passed the half-submerged wreck of the British Cunard ocean liner RMS Lancastria, sunk by the Luftwaffe on June 17, 1940. More than 1,730 people, British nationals and French troops, two weeks after the Dunkirk evacuation, lost their lives on the Lancastria, making it Britain’s worst maritime disaster of all time.

Onward the raiding party went, deeper and deeper into the river’s mouth, until they were just two miles from their destination. Meanwhile, the German antiaircraft guns had stopped firing at the planes and the searchlights had been switched off after Karl-Conrad Mecke, the commander of the 22nd Naval Flak Brigade, became suspicious of the RAF’s odd bombing pattern. Instead of simply dropping their bombs and heading for home, the planes were circling the port and dropping one bomb at a time. Thinking that perhaps the bombing signaled the start of a parachute assault, he ordered the gun crews to be on alert for an airborne raid.

An hour later, a searchlight scanned the water close to the flotilla, but then, just as quickly, was extinguished. No shots were fired at the seaborne raiders. But Mecke was on the alert. At 1:20 am, after receiving reports of a mysterious group of approaching vessels that other commands had dismissed as improbable, he sent a message to all units in the St. Nazaire area to be on the lookout for a landing party.

Now a dozen or more searchlights that lined the banks of the river were switched on and played across the water. A few shots were fired across the Campbeltown’s bow, and a signal light on shore blinked out a challenge. Ready for this, the signalman aboard the ship blinkered back in German, “Wait,” then gave the call sign of a real German destroyer. This was followed by a fake message saying that the ship was damaged and requested permission to proceed “without delay.” The Germans, evidently taking the bait, ceased firing and let the ship pass.

A Royal Navy lieutenant named Frank Arkle, aboard Sub-Lieutenant Mark Rodier’s ML-177, recalled, “At this stage, the [Campbeltown] was flying the German ensign and we were firmly ordered that we must not open fire at all until the ensign was removed and we could all fly our white [British Royal Navy] ensigns again.”

But only a few minutes went by before the Germans, realizing that they had been duped, began bombarding the vessels with fury. The Campbeltown’s signalman flashed out: “You are firing on friendly ships,” and the guns went silent again, but only briefly.

Once more the coastal defense artillery, along with machine guns and rifles, started blazing away, with tracers streaking through the night sky and tall spouts of water jetting into the air from the impact of the shells and bullets.

Now the commandos and naval personnel began firing back, the British ensigns appeared, and the captain of Campbeltown ordered full speed ahead. Dead ahead of her, a few hundred yards away, was the lock gate to the dry dock.

“Four Minutes Late”

At the outer harbor, a German guardship began pumping munitions at the passing flotilla when MTB-314, with Ryder and Newman aboard, flashed by and cut loose with her Oerlikon deck guns at near point-blank range. The German ship went quiet except for the sounds of moaning from her wounded and dying crew members.

Commando Lieutenant John Roderick, aboard Campbeltown, remembered, “The run-in was desperately exciting––the suspense over the haggling about who or what we were, the opening fire from the banks, the silence, and then the final opening up of all the guns. One was filled with admiration for the [Campbeltown’s] gun crews who suffered severe casualties. Lying behind them, we were not entirely inactive as our Bren guns were fitted for this phase, with large pans of ammunition which we fired at as many possible targets as we could make out.”

Lieutenant Arkle on ML-177 added, “There were tracer bullets going in every direction, a very colourful sight because the British tracers were all orange in colour and the Germans were all a blue green. Very pretty! The shells weren’t quite so pretty when they started to fly around the place! Anyway, this went on for some time and the destroyer went to full speed ahead, aiming for the dock gates, but the port line of motor launches started turning in towards their landing spot which was mainly Old Mole on the dockside, and they started to get into some serious fire, and fire broke out on board on several of them, unfortunately.

“We were in the starboard line and when the destroyer hit the dock gates, which it did very accurately, we passed them to starboard, did a big circle round, and passed them under their stern. It was our duty to go into the Old Entrance to the dock where we went alongside and deposited our commandos.”

The Campbeltown became the focus of nearly every German gun surrounding the port, and her hull, deck, and superstructure were hit by the combined weaponry. Still, she did not slow down or falter as her skipper, Lieutenant Commander Sam Beattie, with dead and wounded crew members all around him, plunged forward at 20 knots, heedless of the danger. Ahead of him, MTB-314 was still firing back at the port’s defenders until, at the last moment, it veered off to the right, giving Beattie a clear run at the lock gates.

As author Ford writes, “Suddenly Campbeltown hit the antitorpedo net that protected the lock, but the rush of over 1,000 tons of warship tore through the steel mesh and the destroyer leapt forward unchecked. Seconds later, with a grinding low groan, the ship struck the center of the massive steel caisson and shuddered to a halt. It was 0134 hours; Campbeltown had reached her target just four minutes late.”

The Commandos Disembark

The destroyer smashed into the steel lock gate with such force that 35 feet of the Campbeltown’s bow was crumpled and the entire ship was stuck in an upward tilt of some 15 degrees. The ship’s complement of commandos began dashing through the smoke of the burning craft and leaping onto the dock, firing away with their Sten guns at anything that moved.

Lieutenant Roderick recalled, “Following the crash of the bows which came with surprisingly little jolting, I went quickly forward to reconnoitre the way off the ship; it was a bit of a shambles with many wounded chaps lying about the deck. The gun in the bow of the ship was looking somewhat cockeyed and I could see no obvious signs of life around it. [Major] Bill Copland gave us his usual morale boosting order as we quickly made our way off the Campbeltown.

“Our bamboo ladders had been damaged by gunshot prior to getting off; Corporal [John] Donaldson had charge of one of them when he was killed. However, I managed to find a length of cable down which we clambered onto the dock gate, covering our actions as best we could.

“There was and had been a hell of a lot of firing going on that it was difficult to pinpoint where it was coming from. I cannot remember seeing gunfire coming from the first gun emplacement. I went forward with Corporal Howarth and an explosive of some sort passed over my head and wounded him in the leg. We finished off the crew and moved on with [Lieutenant] John Stutchbury and his section covering fire in turn.

“We next had to clear the ground leading to and over the oil storage tanks. There was a number of Nissan huts into which we threw grenades with the most terrific bangs, and in another concrete building we killed a further batch of the enemy. There is no doubt we killed two more. There was, I believe, a light gun of some sort at the top but I did not go up and see; by this time we were advancing round the seaward side of the oil tanks. John Stutchbury was being given covering fire as he went forward to engage a third group of the enemy. We had quite a large area to cover and with our reduced numbers it was a full-time job keeping our eyes open to all around us.”

The Gunboats Land

While the Campbeltown had been roaring, throttles wide open, for the southern lock gate, six motor launches, ML-156, ML-177, ML-192, ML-262, ML-267, and ML-268, had peeled off from the formation and were heading at full speed toward the Old Entrance to land their commandos. Confusion, chaos, and disaster would soon overtake the landing parties.

As the first boat, ML-192, commanded by Lt. Cmdr. William L. Stephens, maneuvered close to the Old Entrance jetty, a large shell struck the craft. The explosion disabled the engine room, causing the craft to drift out of control and eventually come to a stop against the East Jetty with several casualties on board.

Captain Michael Burn, in charge of the 13 other commandos on ML-192, managed to disembark his men and lead them to their objective, two nearby flak towers, but found them unmanned.

George Davidson, a crewman aboard Stephens’s boat, recalled, “ML-192 was the first ship to be hit. We were about to pass the Old Mole when we were completely stopped. I mean, the machinery stopped––the boat was still moving. The engine room was on fire and, instead of passing the Old Mole, we ran into it.

“On the Mole itself was the lighthouse, at the end, and then a tower with searchlights and closer to the shore, another flak tower. We stopped just short of the flak tower. The boat listed to starboard, which put the mast over the top of the Mole and I thought there was a prospect of getting ashore there. It was going to be difficult, but I thought I could climb the mast and drop onto the Mole. So, I climbed it, to a point when I could see two heads peeping out of the flak tower and I thought it was time to make a move. I think they were as frightened as I was because they never fired at me. They were not expecting mast-climbing folk!

“When I came down again, the ship was well on fire and the skipper ordered us to abandon ship. I gave him a hand to launch a float and after we launched it for the benefit of the non-swimmers, I went over the bow to swim along parallel to the Mole and got up on the beach.”

While this drama was taking place, the third craft, ML-262, commanded by Lieutenant Edward “Ted” A. Burt, approached, carrying Lieutenant Mark Woodcock’s demolition party, whose mission it was to destroy the bridge across the Old Entrance and the two adjacent locks. But Burt was disoriented by the blinding searchlights and overshot his objective by several hundred yards. Behind him, Lieutenant Eric H. Beart, commanding ML-267, suffered a similar problem, and both craft swung wide and prepared to come around again.

The fourth craft, ML-268, under Lieutenant Bill Tillie, saw Burt and Beart miss their landing spots but did not repeat their error. As it got close to the Old Entrance’s steps, Tillie’s boat was torn apart by enemy shells and burst into flames, exploding within minutes. Only Tillie and half his crew, along with two of the 18 commandos on board, were able to reach land.

The fifth boat was Lieutenant Leslie Fenton’s ML-156, but it fared no better than those ahead of it. Fenton was wounded, along with Captain Richard H. Hooper, the commander of the 13 commandos aboard. The boat missed its mark and circled around again, all the while being subjected to accurate German fire. With the engines and steering damaged and casualties mounting, Fenton had no choice but to withdraw ML-156 from the landing zone and head back down the Loire. The crippled boat would later be scuttled.

The sixth and final boat to attempt a landing, ML-177, under Sub-Lieutenant Rodier, somehow survived the storm of flying lead and dropped off its party of 13 commandos, led by Troop Sergeant Major George E. Haines, on the southern side of the Old Entrance. Haines had orders to link up with Captain Hooper’s group and knock out the enemy gun positions between the Old Entrance and the Old Mole, but the sergeant was unaware that Hooper and ML-156 had failed to land. Nevertheless, Haines ran his men through the darkened labyrinth of streets, sheds, and buildings, engaging in wild shootouts with surprised German troops who were doing their best to halt the attack.

Setting the Explosives

Braving the fire, Robert Ryder’s command boat, MGB-314, then managed to land Lieutenant Colonel Newman and his headquarters staff at the steps of the Old Entrance, where the bullets and shells were still flying thick and fast. William Savage, an able seaman aboard 314, was firing a deck gun with great accuracy. Although he had no gun-shield and was in an exposed position, he continued blasting away until he was killed at his gun. His actions would earn him a posthumous Victoria Cross.

Royal Navy Lieutenant Frank Arkle, aboard ML-177, recalled, “At this stage, Commander Ryder came alongside us in his MGB and gave us the instruction to let go our lines and to go alongside the Campbeltown and pick up as many crew as we could and take them home to England.” Meanwhile, the commandos that had leaped from Cambeltown were still in the thick of the fighting on the docks. Lieutenant Brett (who was shot in both legs before starting his task) and his men were attacking the southern caisson of the dry dock, trying to disable it. In their effort to reach the northern lock gate and caisson 300 yards away, Lieutenant Burtinshaw’s men braved a fusillade of concentrated enemy fire only to discover that its design was different from the one on which they had practiced back in England.

Unable to enter the inner workings of the caisson, Burtinshaw’s men strung the explosives as best they could, even while German machine guns and sharpshooters were raking the commandos. Burtinshaw himself went down mortally wounded. A sergeant named Carr took over for his fallen leader and detonated the explosives, causing serious damage to the northern caisson. Lieutenant Chant, who had been hit even before he had disembarked from Campbeltown, carried on and, with his party, placed their charges 40 feet below ground beneath the pumping house, destroying it. Lieutenant Bill Etches, in overall command of both Lieutenants Smalley and Purdon, saw to it that those teams destroyed the two winding huts.

But the Germans increased the intensity and accuracy of their fire. The bodies of Burtinshaw and six other commandos had to be left where they fell, for the entire group faced annihilation if it did not immediately withdraw and make a run for the evacuation point at the Old Entrance, more than 300 yards away. The two launches that had earlier overshot their mark––Burt’s ML-262 and Beart’s ML-267––returned to the Old Entrance and once again tried to make a landing despite the torrent of lead being poured into the confined area. Burt bravely landed Woodcock’s demolition team along with Lieutenant R.F. Morgan’s protection squad at the northern quay before being forced to cast off.

But Morgan’s squad had gone inland only a short distance when it came running back to the quay, demanding to be allowed to reboard the craft; one of the men had seen a German tracer round burn through the air and, mistaking it for the signal to retreat, had thought it was a flare ordering the landing party to pull back. Burt’s craft, still being splintered by enemy fire, dallied long enough for Morgan’s men to jump back on.

The Withdraw

At about this same moment, Lieutenant Smalley’s team appeared, having accomplished its mission at the northern caisson. Smalley and his men, rather than continuing on to the Old Mole as planned, saw Burt’s craft and ran to it; Burt put back into the dock and let them scramble aboard. Trailing a cloud of smoke and exhaust, ML-262 roared off toward open water, but it again became the target for every German gun within range and Smalley was killed. ML-262, although badly shot up, barely escaped.

During the melee, Beart’s ML-267 approached the Old Entrance to land its load of commandos, Newman’s reserves, but no sooner had a few disembarked at the southern steps than the intensity of fire forced Beart to back off. The boat burst into flame and began to drift helplessly, and those on board abandoned it; many were raked by machine-gun fire while in the water. Lieutenant Beart, along with 10 of his crew and eight commandos, were killed.

Finally, MTB-74, one of the two motor torpedo boats under Lieutenant Mickey Wynn, entered the fray. Wynn torpedoed the lock gates that closed off the Old Entrance from the submarine basin (the time-delay fuses in the torpedoes would go off two days later), then headed over to assist Ryder (MTB-314) and Rodier (ML-177) in evacuating the men from the crippled Campbeltown. Beset by enemy fire and unable to set the underground fuel storage tanks alight, Lieutenant Roderick and his team fought their way toward the assembly point, Newman’s temporary headquarters near the Old Entrance.

“Our movements were obviously being watched, as we had to move in between bouts of fire,” Roderick reported. “It was while running for cover, carrying the Bren guns, that I was shot through my left thigh. It came as a complete surprise; I was only aware of being knocked head over heels and the Bren leaving my hands. I moved quickly behind a stanchion and eventually made my way towards Colonel Newman’s assembly point where the rest of my party had foregathered.”

Landing more commandos at the Old Entrance was impossible, so the following squadron of six motor launches decided to land at the nearby Old Mole, but without any better success. Lieutenant T.D.L. Platt’s ML-447 dropped off Captain David Birney’s 14 men, but they were greeted by a withering stream of bullets from the bunkers there. The launch was hit and its Oerlikon guns and gun crews knocked out. Limping close to the Old Entrance, Platt tried to approach the stone steps, but the craft was then ripped apart by a large-caliber shell. Only a handful of men were able to make it to the steps; the rest were either killed outright by the blast or flung into the dark waters of the harbor where they drowned.

Luckily, Lieutenant Thomas Collier, commanding ML-457, was able to get right up to the steps and deposit his three teams of commandos. The first was a control party led by the dockyard demolition instructor, Captain Bill Pritchard, the second was Lieutenant Walton and his four-man demolitions team, and the third was a four-man protection party under Lieutenant William H. “Tiger” Watson.

Following close behind Collier’s boat was Lieutenant Norman Wallis’ ML-307, carrying Captain E.W. Bradley and six commandos. But Wallis struck an underwater obstacle and became grounded; enemy fire now concentrated on the stranded vessel. Wallis skillfully managed to extricate ML-307 from its perch and, at Bradley’s direction, began engaging the German guns and searchlights along the quays and jetties that were threatening to defeat the raid.

In ML-307’s wake came ML-306 under Lieutenant Ian Henderson, followed by ML-443, commanded by Lieutenant K. Horlock, and ML-446 with Lieutenant Dick Falconar in charge. But the waters around the Old Entrance were choked with burning and disabled motor launches, wounded men, and flying lead, and the boats could not approach. The three skippers all made the decision to withdraw in hopes of finding another, less deadly place where they could set their commando teams ashore. It was a futile hope.

Commandos Captured

Aboard Rodier’s ML-177, closing in to rescue Campbeltown’s survivors, Frank Arkle recalled, “In order to ram the dock gates as it had, the Campbeltown had had to go through some antisubmarine nets in order to get there, and a lot of these nets were still hanging off its sides as we were trying to come alongside; we had to be very careful of this in order not to get them tangled around our own propellers. However, we managed to get our bow alongside and took off a lot of the crew including the captain [Sam Beattie] and several of his officers, including the medical officer, a lot of the wounded, and some commandos.”

Backing away from the destroyer’s stern, Rodier headed seaward for safety, but it was a short journey. Arkle said, “We sped as fast as we could, which was a full 18 knots, down towards the open sea. We found ourselves coming more and more under fire from shore-based batteries, so we thought it was time to get our smoke screen working. We were just working on this when, unfortunately, the first shell hit us, which was into the engine room. It apparently shifted one of our engines right up on top of the other and they were both out of action.

“I was on the stern and Mark Rodier was on the bridge with Commander Beattie. Beattie came down towards the funnel and we were standing, the two of us, aft when another shell hit us. I can see to this day the funnel folding apart, what appeared to be quite slowly, and the shell bursting in the middle of it. To my benefit poor old Mark was standing exactly between me and the shell, and he took the brunt of the explosion which would have hit me if he hadn’t been there. I was hit all down my left-hand side, but not anywhere else particularly, except my face.

“I felt my right eye on my cheek and I was convinced that my right eye had been blown out of my head and was hanging down my cheek, and I felt there was only one thing to do about this, so I plucked it out and threw it overboard. I then went down to the wardroom although we were on fire amidships and got something to put round my head as a sort of bandage over my wounded eye, and I was limping because my left foot was also mucked about quite a bit.”

ML-177 was burning fiercely. Rodier was dead, as was Lieutenant Tibbitts, the man who had set the time fuse in Campbeltown. Both Beattie and Arkle agreed that nothing more could be done to save the craft, so the order was given to abandon ship. Arkle and a couple of commandos grabbed onto a piece of floating wreckage.

“We decided to swim for the nearest shoreline,” he said, “but I soon realized that we were completely wasting our energy because we were just going round in circles. So I decided to try and get a flask of whiskey out of my pocket, a small pewter flask. I discovered, in the end, that my hands were so cold that I couldn’t undo the button on my hip pocket to get the flask out so I had to give up, and I think after an hour or two in the water, although we kept moving to try and keep our circulation going, we were beginning to get seriously affected by the cold.”

At about that time, a large vessel, an armed German trawler, found the floating survivors and put scramble nets over the side. Somehow, Arkle managed to climb up and get on board. “By this time I think I had lost rather a lot of blood from a large hole I had in my left hip. We were told to lie on the deck. There were German sentries with rifles keeping an eye on us and eventually one of them came with cups of ersatz coffee.” Also taken prisoner was Commander Beattie.

Scenes of survival were also still playing out near the Old Mole. After abandoning the listing ML-192, George Davidson recalled that the Germans captured the crew and “marched us off in a southerly direction. On the way, there was a lot of gunfire. We were ducking and dodging, and I spotted some rolls of wire netting, like chicken wire, and so I slid in between them. I just laid doggo and they marched off without me. That was before two o’clock in the morning and I was still there by daylight. I knew I had to make a break for it, but ran into a bunch of Germans and was immediately taken prisoner.

“I was quite concerned because there were some trigger-happy ones amongst them, but fortunately the officer who was in charge of them seemed to be a steady type and ordered me to walk over towards the Mole and made me stand with my back to the parapet, and I thought it was curtains.” Luckily, Davidson was only taken prisoner and not shot.

“We’ll Just Have to Walk Home”

Meanwhile, team after team of commandos withdrew toward the Old Entrance and, by 2:30 am they had assembled at Newman’s headquarters, ready for evacuation by boat. But there were no more boats to be had. The small harbor was already a scene of mass devastation. The motor launches that had been lost with their crews on the way in bobbed helplessly about and burned fiercely. The smoking wreckage, interspersed with huge blazing pools of fuel and the floating bodies of dead sailors and commandos, were eerily highlighted by the searchlights.

As more and more groups piled into the headquarters, it became clear to Colonel Newman that the commandos were in an untenable position. Most of those who arrived were wounded, some badly, and incapable of being moved. With the undiminished volume of fire outside, it also became clear that escape back to either the Old Entrance or the Old Mole was out of the question; Newman’s escape route was being swept by machine guns and large-caliber weapons. The only option, then, was to dash out of the building, cross the bridge into the city of St. Nazaire, disperse, and make a run for it and hope to disappear into the countryside. Perhaps some French underground groups would help the commandos get back to Britain.

Newman gathered his men and told them with typical British aplomb, “Well, chaps, we’ve missed the boat. We’ll just have to walk home.” At 3 am on March 28, the commandos, each supporting a wounded comrade, dashed out the door and, in one final display of selfless heroism, fought their way through the warehouses fronting the submarine bay and over the bridge into town.

Lieutenant Roderick vividly remembered the breakout attempt. He and his men made a dash toward the bridge, with Captain Roy, Lieutenants Len “Hoppy” Hopwood and Bill Watson, Sergeant Alf Pearson, and others acting as forward section. “This stage was particularly exciting and fraught with surprises,” said Roderick, “as all house and street fighting must be. It was during one of these scuffles that Tiger Watson was shot through the humerus; I gave him an injection of morphine.

“On leaving Tiger as comfortable as possible, Hoppy Hopwood, Alf Pearson, and one or two others whose names fail me were searching through some warehouses, as attempts to get across the bridge at this time were suicidal. It was about this time I was wounded in the head by a grenade.

“It was decided that we should find a suitable place to hide and this we did, making a nest of full cement bags high off the ground. Alf Pearson had been badly wounded through the left shoulder and was out of active participation and we were, by this time, a pretty ropey lot. We did, however, have a very nice hideout and on a number of occasions in the next few hours, groups of Germans, who were by this time into the area in reinforcement, passed us by in their search parties.”

By early morning, German roadblocks had sealed off the streets and the commandos, low on ammunition, had run out of options. Roderick said, “It was only in the light of day at about 10:30 am that a German searching high up in a warehouse on the other side of the road saw a bandaged head or limb through some bomb damage in our warehouse wall and gave the alarm. In next to no time the place was alive and we surrendered ourselves. Opposition would have been simply futile and life was still very sweet. Our captors were not particularly pleased and pushed us against a wall and searched us. We thought we’d had it.”

Almost all of the commandos were either killed or captured. Eventually, only five men would return to England.

Five Boats Return

After the motor launches had retired out to sea, the German destroyer Jaguar closed in to intercept the flotilla some 45 miles from St. Nazaire. Firing a burst at ML-306 and ordering it to halt, the Jaguar’s commander was startled by the British reply: a blast of return fire from a Lewis gun being operated by 23-year-old commando Sergeant Thomas F. Durrant.

As a one-man assault party, Durrant kept the German ship at bay until, after a running gun battle, the sergeant was killed. His courage earned for him the Victoria Cross, posthumously. Durrant is one of very few men to have received their VC on the recommendation of an enemy officer, the destroyer’s captain.

Of the 18 original raiding boats, only five craft were able to rendezvous with the two British destroyers: ML-306, ML-307, ML-443, ML-446, and MGB 314.

The Raid’s Last Hurrah

As the commandos who were still alive and had not been evacuated either fought last-ditch skirmishes, eluded the enemy, or were taken prisoner by the Germans, the last and most spectacular act of the operation took place.

By mid-morning on March 28, the battered Cambeltown, still beached at its upward angle atop the lock gates had drawn quite a crowd of spectators. Some had even climbed aboard her to marvel at the Brits’ clever handiwork, while others were below decks inspecting the thick wall of concrete and no doubt surmising that the concrete was there simply to provide extra strength to the ship’s prow that had been used as a battering ram. No one realized that, on the other side of the concrete slab, the acid in the pencil detonator was about to eat through the last bit of copper wire.

While the object of everyone’s attention was drawing bemused glances, it suddenly vaporized in a blinding flash and mighty bang. Pieces of steel and human bodies were hurled everywhere. The lock gates split open, releasing a tidal wave of seawater into the dry chamber and causing two German tankers within to capsize and sink.

Lieutenant Roderick recalled that he and a few mates were being held captive on a small boat in the river when the Campbeltown exploded. “We were left with our guards but everybody else ran to see what it was all about. Shortly afterwards, we were bundled into a truck and taken into the town where we were put into a private house prior to being moved to the hospital at Le Baule.”

The damage was stupendous. For blocks around, windows were blown out and weak structures toppled. Vehicles were overturned and people knocked flat. Some buildings caught fire. Of the German defenders, scores were dead or wounded. The Normandie Dock was a shambles and was rendered unusable until 1947. There was no chance the Tirpitz or any other German ship would ever use it.

“The Greatest Raid of All”

Operation Chariot had been a successful, if terribly expensive, raid. Everyone who took part in the St. Nazaire raid, deemed by the British “the greatest raid of all,” covered themselves with glory, even at the cost of their lives. Five Victoria Crosses, Britain’s highest award for valor, were earned on the fateful night (by Beatty, Newman, Ryder, Savage, and Durrant). In addition, four Distinguished Service Orders, 17 Distinguished Service Crosses, 11 Military Crosses, four Conspicuous Gallantry Medals, five Distinguished Conduct Medals, 24 Distinguished Service Medals, and 15 Military Medals were awarded for the action at St Nazaire.

But the casualties were heavy. Most of the small craft were sunk or scuttled. Of 611 soldiers and sailors who took part, 168 were killed and 200 were taken prisoner.

This success, and the commando raid on the isle of Sark in the Channel Islands on October 3-4, 1942, prompted a furious Hitler to issue his infamous “Commando Order.”

It decreed, “From now on, all men operating against German troops in so-called Commando raids in Europe or in Africa are to be annihilated to the last man.” The protections of the Geneva Convention would not be extended to commandos.

More than six decades later, the British still consider the raid on St. Nazaire one of the most heroic and successful of the war; plaques and monuments in memory of the raiders have been erected at the port. A third of the British soldiers and sailors killed during the raid are buried at the Escoublac-la-Baule War Cemetery, 11 miles west of St. Nazaire.

Perhaps Lord Lovat, who would lead British commandos ashore at Sword Beach on D-Day, June 6, 1944, summed it up best when he wrote, “St. Nazaire was unquestionably the most spectacular sea-borne raid carried out in the Second World War.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments