By Erik Petkovic

On September 3, 1939, when Great Britain and France declared war on Germany, the Kriegsmarine only had 46 operational U-boats, the majority of which were used for training. More than half of them were the Type II and its four variants, which were all coastal submarines with limited range. Given the circumstances, they were kept close to the Fatherland. Most were withdrawn from the Atlantic and started operating in the North Sea until longer range and more capable U-boats were available.

Meanwhile, German design and engineering continued to advance the U-boat. Applying lessons learned from World War I in conjunction with extensive trials, which included tactical scenarios, the Kriegsmarine continued to develop its underwater fleet. Improvements were designed, tested, and implemented, not only in the U-boats already in service, but to the overall design.

Type I and Type VII U-boats were being launched at shipyards simultaneously throughout Germany. The first Type VIIA U-boat was tested against the Type IA. Despite the initial Type VII carrying three fewer torpedoes than the Type IA and the Type IA having a better turning radius and faster surface speed, the Type VIIA displayed better underwater performance. After close comparison, Admiral Karl Dönitz, commander of the Kriegsmarine U-boat fleet, completely abandoned the Type I and discontinued the coastal Type II. Dönitz chose to concentrate on perfecting the Type VII and Type IX. The improved designs incorporated more torpedoes, a faster surface speed, and a better turning radius. The Type VII would become the most produced U-boat during the war.

One of the shipbuilders which produced Type VII for the Kriegsmarine was Flender Werke AG. The shipbuilder was situated southeast of Kiel in the second largest city on the German-Baltic coast, Lubeck. Over the course of the war, Flender Werke AG produced 42 U-boats. U-85 was one of only five Type VIIB U-boats built in Lubeck.

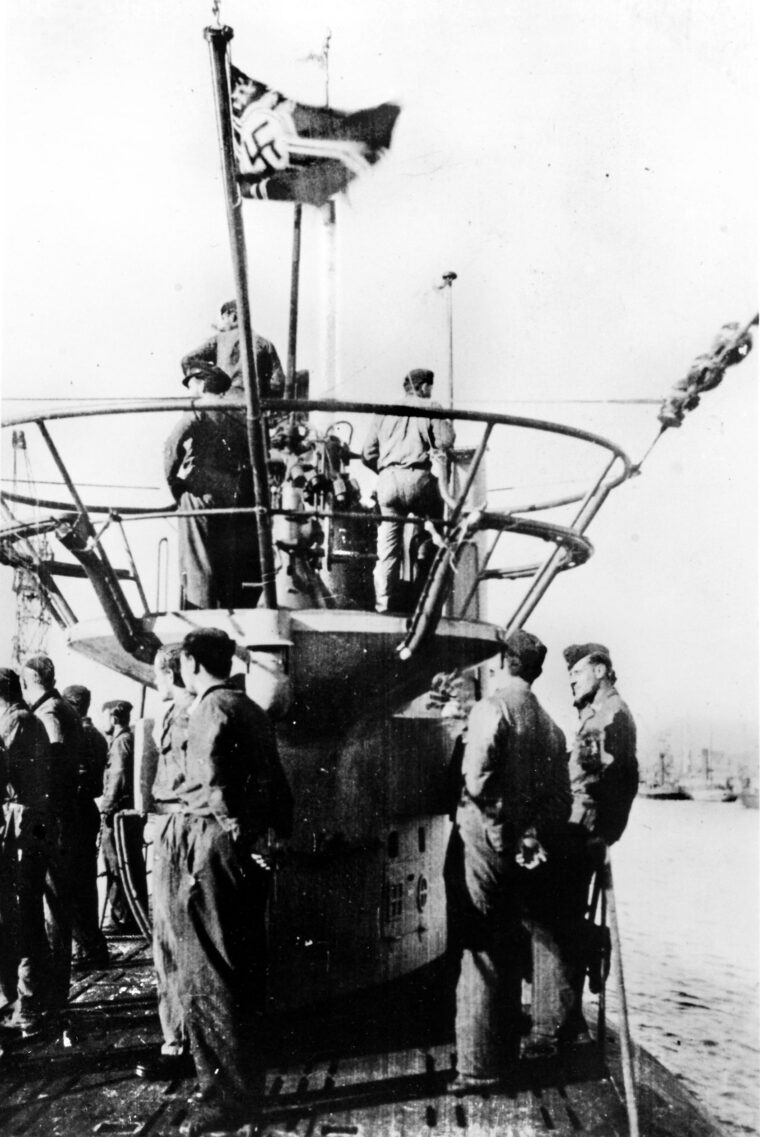

U-85 was ordered on June 9, 1938. The keel was laid on December 18, 1939. U-85 was launched on April 10, 1941, and officially entered the Kriegsmarine two months later on June 7, during commissioning. One of only 24 Type VIIB U-boats produced for the Kriegsmarine, U-85 was attached to the Third Flotilla based at Kiel and La Palice.

The Type VIIB incorporated the recommended changes made by both the U-boat trial committee and Dönitz. The addition of a second rudder improved the excessive turning radius of the Type VIIA. The aft torpedo tube was repositioned inside the pressure hull. This allowed for more torpedo storage inside the pressure hull and additionally outside the pressure hull beneath the deck. Speed was also increased with the introduction of a superdrive for the diesel engines. An increase in overall length and larger fuel tanks expanded its range.

At 26, Eberhard Greger already had several years of combat to his name when he was given command of U-85. In addition to being Second Watch Officer aboard the destroyer Wolfgang Zenker from February to October 1939, Greger was First Watch Officer for legendary commander Kapitanleutnant Fitz-Julius Lemp aboard U-30. Lemp, a Knight’s Cross holder, was at the helm when U-30 sank 17 Allied vessels totaling 86,490 tons. In October 1940, Lemp transferred to U-110—a Type IXB. Greger joined Lemp as First Watch Officer until he enrolled in the U-boat commander course. U-110 was captured by the British on May 9, 1941, and the Royal Navy obtained an enigma machine and, more importantly, an up-to-date codebook. Lemp died during the attack.

After commissioning, Greger and U-85 spent most of the summer of 1941 undergoing hull and engine trials conducted by the U-boat Acceptance Commission (UAK-U-Bootsabnahmekommission). Handling trials were administered by the Technical Training Group for Frontline U-boats.

From August 11 to August 28, U-85 held firing exercises in Trondheim Fjord, Norway. During the exercises on August 13, the small German destroyer T-151 rammed U-85 in 45 feet of water. U-85’s number one diving tank and steering gear were damaged, but it didn’t sink. After it was repaired and given a final overhaul in dry dock, the crew painted a wild boar logo on the front of the conning tower as a tribute to Oberleutnant zur see Eberhard Greger—the German translation of “Eber” is boar. U-85 was ready for war.

On August 28, U-85 departed Trondheim on its first war patrol. Assigned to the Markgraf Wolfpack, U-85 headed north through the North Sea with 13 other subs destined to patrol the waters off southwestern Iceland. Less than 12 hours after departing, alarms rang out. U-85 was sighted by an Allied aircraft and forced to crash dive at 9:04 p.m. Thirty minutes later, U-85 surfaced and continued on its cruise. The following day U-85 was forced to crash dive again as it was spotted by another Allied aircraft. On the third day, U-85 entered the North Atlantic and spotted a freighter, which escaped before an attack could be coordinated.

On Sunday, August 31, at 11:40 a.m., U-85 spotted a steamer and altered course to head off the unknown vessel. At 12:30 p.m. U-85 submerged for an attack that was called off as the steamer was deemed to be too small to waste a torpedo on.

On September 2, a patrolling aircraft spotted U-85 and dropped three depth charges that did no damage. U-85 spotted U-105 later that evening and exchanged recognition signals and accounts of what had transpired since the beginning of the cruise.

U-85 reached the waters south of the Denmark Strait on September 4 and had to crash dive three times over the next 24 hours as it was spotted by coastal surveillance planes.

On September 9, southeast of Greenland, U-81 and U-85 found convoy SC-42. Greger radioed that the convoy contained as many as 65 ships—a massive discovery with the potential for inflicting significant damage. The entire Markgraf Wolfpack was redirected to Greger’s position. SC-42 was protected by Canadian escort group EG.24 consisting of the destroyer HMCS Skeena and the corvettes HMCS Kenogami, HMCS Alberni, and HMCS Orillia.

As the wolfpack descended upon its prey from various directions, U-85 heard a distant explosion. U-81, under the command of Kapitanleutnant Friedrich Guggenberger, hit the British steamer Empire Springbuck on the port side with two torpedoes. The steamer exploded and disappeared quickly beneath the surface, and 39 lives were lost.

U-85 had to crash dive again just after noon and, while submerged, fired five torpedoes at the convoy that did not find their mark.

Surfacing at 3:45 p.m., U-85 sounded the alarm five minutes later when two vessels were sighted. The closest was an escort ship that was curiously stopped dead in the water. Suspecting a trap, U-85 disengaged and left the area. U-85 surfaced at 4:50 p.m. and followed the convoy from a distance until forced to crash dive after being sighted by an airplane. U-85 continued to follow the convoy while navigating through an iceberg field.

Sighted by a destroyer the next morning, U-85 was forced to alter its course after it opened fire. The destroyer dropped a depth charge on U-85 just over 20 minutes later but it inflicted no damage. U-85 remained submerged for the next 75 minutes.

Nearly three hours later U-85 found the convoy and fired multiple torpedoes, hitting the British steamer Thistleglen, killing three sailors and sending 2,400 tons of pig iron and 5,200 tons of steel to the bottom of the North Atlantic. U-85 descended to a depth of 308 feet to escape the heavy barrage of depth charges. Greger surfaced three times over the next several hours but was forced to immediately dive because of aircraft overhead.

On September 11, U-85 surfaced in an attempt to repair damage suffered during the earlier depth charge incident. At 9:45 a.m., Greger ordered a test dive. It did not go well. U-85 was in a “state of limited readiness to submerge.” Greger had no choice but to head to the U-boat pens at St. Nazaire on the French coast.

After 22 days at sea, U-85 arrived at St. Nazaire. Greger was disappointed his first war patrol was cut short. Even though U-85 claimed only one kill, Greger’s spotting of the convoy was a major success. A total of 16 Allied ships, 68,259 tons, were sunk and four additional vessels were damaged.

Following repairs, U-85 departed for Lorient on October 11, where it took on provisions and fuel. On October 16, U-85 departed Lorient. Not much is known about U-85’s second war patrol other than its ending in failure. U-85 was continuously plagued by bad weather and limited visibility for much of the 43-day cruise. U-85 chased two convoys, but there is no evidence of any success and it returned to Lorient low on fuel and a full complement of torpedoes.

On January 10, 1942, U-85 began its third war cruise with orders to patrol off Gibraltar and then enter the Mediterranean Sea. One week later while chasing a convoy, Greger received new operational orders to head for American waters.

On January 21, U-85 sighted a lone steamer heading toward the British Isles and immediately submerged. At 6:42 p.m., U-85 fired four torpedoes. Two crewmen aboard U-85 claimed two detonations were heard. The U-boat surfaced and claimed to have seen a steamer with a list. U-85 submerged to stealthily approach the stricken steamer, surfacing 21 minutes later to find no sign of it. Greger searched until after midnight for debris, but nothing was ever found. No Allied records confirm this incident.

Off Newfoundland on January 28, U-85 went through a “baptism by fire.” At 1:48 p.m., the submarine was rocked when a depth charge exploded near the hull. A Lockheed Hudson coastal reconnaissance aircraft piloted by Donald Francis Mason of the U.S. Navy, was making an anti-submarine sweep astern of convoy HX-172 when he sighted a periscope. Two depth charges were dropped approximately 25 feet apart.

According to the official U.S. report of engagement, U-85 was “apparently completely surprised” by the attack. “Plumes of the explosions were seen to spread, one on either side of the periscope, estimated distance 10 feet from wake line and nearly abreast the periscope. The submarine was lifted bodily in the water until most of the conning tower could be seen. Headway of submarine seemed to be killed at once and she was observed to sink from sight vertically. Five minutes later, oil began to bubble to the surface and continued for ten minutes.” The pilot famously reported “Sighted sub, sank same.”

U-85 surfaced 70 minutes later undamaged.

On February 8, U-85 met with U-654 under command of Oberleutnant Ludwig Forster, and the two U-boats jointly pursued convoy ONS-61. Forster hit the French corvette FFL Alyssa with a torpedo on the port side. Thirty-six crew were lost. Thirty-four survivors were picked up by the corvettes HMCS Moose Jaw and HMCS Hepatica. U-85 fired three torpedoes at the convoy. All three missed.

The following day in continued pursuit of ONS-61, U-85 sighted a steamer. At 11:28 a.m., U-85 submerged for an attack, but the British steamer Empire Fusilier zigzagged away. An hours-long pursuit commenced. At 10:20 p.m., U-85 fired a spread of three torpedoes. Greger scored one hit, and Empire Fusilier sank immediately with a loss of nine crewmen. Thirty-eight survivors were picked up by the corvette HMCS Barrie and later landed at Halifax, Nova Scotia. Low on fuel, U-85 started the 1,000-mile return to St. Nazaire.

After provisioning and refitting, U-85 left for its fourth, and final, cruise on March 21. Two days west of St. Nazaire, depth charges were heard in the distance. Greger kept U-85 submerged until he deemed it safe to surface on the fourth day and then proceeded westward on the surface toward America’s East Coast. U-85 carried two enigma machines. Designated Schlussel M, the four-wheeled enigma was the latest cipher technology.

Little is known about the trans-Atlantic crossing after the fourth day other than a diary entry noting “fine weather and a sea as smooth as a table.” The good weather only lasted a few days. By March 29, gale force winds battered U-85. The winds and seas were so heavy that several torpedoes inside U-85 shifted. The following day the electric motors were damaged due to the incessant heavy seas. On March 31, the gale fizzled out. On April 5 at noon, U-85 reported “magnificent sunshine just off America.” Two days later U-85 was 300 nautical miles from land and 660 miles from Washington D.C.

An alarm sounded on April 9, and the contact turned out to be a buoy. U-85 had been at sea for nearly three weeks, and the crew was on edge. The following day, U-85 spotted a lone freighter traveling outbound from New York. The Norwegian-flagged Christina Knudsen was headed to Cape Town, South Africa, hauling general cargo and nitrate. Greger fired two torpedoes, sinking it with all 33 hands.

Greger continued south toward Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, spending the daylight hours running submerged or sitting on the bottom. U-85 surfaced only at night to hunt for ships under the cloak of darkness.

On April 13, U-85 arrived off the North Carolina coast and sat on the bottom in shallow waters off Bodie Island Lighthouse, just north of the Oregon Inlet. Greger could not afford to surface in daylight with only shallow waters beneath him should he need to run and hide.

The USS Roper, a destroyer commanded by Lieutenant Commander Hamilton Wilcox Howe, departed Norfolk Naval Base that same night for an anti-submarine patrol off the Outer Banks. A 1926 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy Howe, now 37, had been well seasoned in the early stages of the Battle of the Atlantic. Just two weeks earlier, Howe and the USS Roper had been on hand to pick up 70 survivors from the American passenger liner City of New York—torpedoed by U-160 in the same waters they were heading for. Howe was joined by Commander Stanley Cook Norton, commander of Destroyer Division 54.

An aging but sturdy vessel, the USS Roper (DD-147) was a Wickes Class four-stack destroyer commissioned on February 15, 1919. Roper was armed with five 3-inch guns, four .50-caliber machine guns, six torpedoes, two racks of depth charges, and Y-guns and K-guns for propelling the depth charges at distance.

At 11 p.m., Howe retired to his cabin, as did Norton. Ensign Kenneth M. Tebo, the officer of the deck, commanded Roper’s bridge and continued south. Six minutes after midnight on April 14, Roper made a sonar contact at a range of 2,700 yards. The captain later reported, “The night was clear, with many stars visible; the sea was very nearly calm, and the water phosphorescent. A wind of force one was blowing from the Southeast. Bodie Island Light and Bodie Island lighted Bell Buoy No. 8 were discernible to starboard.”

As Roper tracked the sonar contact, the sound operator was performing echo ranging on the object. The range decreased as the bearing “began drawing to the left.” When the range closed to 2,100 yards, a wake and small silhouette were seen. The sonar operator heard “rapidly turning propellers.” The vessel appeared to be turning away. Howe and Norton were awakened and reported back to the bridge.

Greger surfaced U-85 in an attempt to outrun Roper and reach deeper water as quickly as possible. Roper’s sound operator and radar operator concurred on the distance and speed of the fleeing vessel. Tebo increased speed to 20 knots, and Roper was gaining on U-85. Knowing that U-boats had a stern torpedo tube, Howe maintained a slight starboard position from U-85’s wake. The precaution paid off when, at a range of 700 yards, U-85 fired a torpedo that passed Roper harmlessly to port. General Quarters echoed throughout the ship.

As they closed to within 300 yards, U-85 turned sharply to starboard. Trapped in only 100 feet of water, Greger had no choice but to fight. Men poured out of U-85’s conning tower to man the deck gun. Executive officer Lt. Williams Winfield Vanous tracked the sub with Roper’s powerful 24-inch searchlight for the first visual of U-85.

When the searchlight caught the Nazi sub again as it continued turning hard to starboard, Chief Boatswain’s Mate Jack Edwin Wright used a .50-caliber machine gun to cut down the Kriegsmarine sailors trying to get to the 88mm deck gun.

Howe later wrote that Wright “opened fire so promptly and effectively that he was a major factor in bringing about the destruction of the submarine. He raked the submarine in the vicinity of her gun and prevented every attempt by the crew to man this gun and counter attack Roper. The promptness and accuracy of this fire undoubtedly materially hastened the decision of the submarine commander to scuttle, and saved this vessel from possible damage and loss of life.”

Coxswain Harry Heyman manned Roper’s No. 5 three-inch gun, scoring a direct hit just aft of the conning tower below the waterline. Heyman had only replaced the regular gun captain two days earlier. Firing a large caliber gun required a team. Seaman John Nicholas McCarter, Seaman Woodrow W. Darden, Seamen Harold E. Hanshaw, Robert D. Orr, and Lon Howser, and Machinist Mate Frank S. Bukovics assisted Heyman on pointing, training, sighting, and loading the three-inch gun.

Only two of Roper’s guns were fired. The others could not be brought into operation—two misfired, probably due to ammunition failures. The casings were removed and inspected. All showed large indentations, which meant the firing pins had struck the casings. The sailors believed primer failures had been caused by bad weather.

“The guns are kept half-loaded at all times when at sea,” Howe noted, and it was difficult to “protect the ammunition from rain, sun, and spray.” Unfired for three weeks, the ammunition left inside the guns was never rotated.

U-85 began to sink slowly, stern first. It is surmised Greger gave the order to scuttle as U-85 slowed and came to a complete stop prior to the direct hit. Men rushed out of U-85 as it went down. Howe reported approximately 40 sailors in the water.

The sound operator aboard Roper heard an “excellent sound contact” in the water. Those on Roper’s bridge believed this to be another U-boat hunting with U-85, but in all likelihood, this was U-85 settling on the bottom. Unwilling to put Roper at undue risk if another U-boat was on the prowl, the American officers decided not to rescue U-85’s men in the water. Instead, Roper powered through the middle of the area while they were all yelling for help and dropped 11 depth charges. All the men in the water were instantly killed.

It was too dark to see any debris in the water, and it was also deemed too dangerous to wait until daylight in case U-85 was part of a wolf pack. Roper departed the area.

At daybreak a U.S. Navy PBY Catalina patrol plane commanded by Lieutenant C.V. Horrigan arrived on scene to conduct a visual assessment. “Suspicious oil slicks and bits of debris were investigated.” Not liking something that he saw, Horrigan dropped a depth charge.

At 7:06 a.m., two additional planes arrived and spotted floating bodies on the water’s surface. The planes dropped smoke floats in order to get Roper’s attention. Nine minutes later, Roper released two lifeboats and “commenced recovering bodies and floating articles.”

At 7:27 a.m., an observation blimp arrived and circled Roper to provide a set of eyes from the sky. As many as seven planes assisted in aerial surveillance throughout the morning. In less than a half hour, the first lifeboat returned to Roper with five German bodies. Within minutes, 15 more were recovered.

Just before 9 a.m., Roper’s sonar operator detected “a sharp echo at a range of 2,700 yards.” Seven minutes later, Roper dropped four depth charges. “One very large air bubble and one smaller one appeared, together with fresh oil,” according to a report. The blimp dropped flares on the spot to assist Roper with visual awareness and reported a “continuation of the air bubbles.”

At 9:32 a.m., the last of 29 bodies was recovered. Howe reported two additional bodies were permitted to sink after a thorough search for “articles of possible use to Naval Intelligence.” Howe did not provide a reason for not recovering these bodies; however, it is thought that they were mauled from the depth charges. Two of the bodies appeared to be officers, although Greger’s body was never located. Two others had escape lungs and mouth pieces inserted. This indicates the two men escaped after U-85 sank. Fifteen empty life jackets were seen floating on the surface along with six escape lungs. Two diaries were discovered and brought aboard Roper for safe transfer to Naval Intelligence. They belonged to Seaman Eric Degenkolb and Stabsobermaschinist Eugen Ungethum.

Just before 10 a.m., Roper dropped two additional depth charges over the largest air bubble to ensure the U-boat would never again hunt. Roper placed an orange buoy about 250 yards from the largest air bubble to mark the location and returned to Lynnhaven Roads that afternoon. A report was made to the Commandant of the Fifth Naval District.

At Lynnhaven Roads, the bodies of the 29 Germans were transferred from Roper to the U.S. Navy tug Sciota (AT-30). The bodies were delivered to the naval base at Norfolk, each transferred via stretcher to a truck which delivered them to a small hangar at Naval Air Station Norfolk for initial examination. Each body was examined, photographed, searched for personal effects, and identified. A report was issued for each examination. Fingerprints were taken, and all personal effects were individually dried, wrapped, and packaged with a serial number.

The Norfolk Naval Base needed the space, so the bodies had to be moved, but a report noted that there was an “insufficient supply of caskets available at the U.S. Naval Hospital, Portsmouth, Va., and in the Norfolk area and private undertakers could not guarantee delivery of the required number in time to be of use.”

Contact was made with Colonel Keith Ryan at the Veterans Administration in Kecoughtan, Virginia. Ryan transferred “twenty-nine standard Veterans Administration specification caskets and shipping boxes from his stock.” The U.S. Navy was billed $33.02 for each casket, and $8.13 for each shipping box.

On April 15, each body was placed into a casket, sealed in a shipping box, and transported under military guard to the Hampton National Cemetery, Hampton, Virginia. The procession consisted of Navy Lt. A. J. Bush, Army Lt. Splain, and a squad of 24 seamen.

The procession was met by Provost Marshal Major C.P. Wade, eight senior and junior Army officers, 20 military police officers who acted as honorary pallbearers, and 52 prisoners from Fort Monroe who dug the 29 graves. The Germans were buried at 8 p.m. The “firing party fired three volleys” while Taps was played.

For their actions in the sinking of U-85, Heyman, Tebo, Vanous, and Wright received Silver Stars. Howe and Norton received the Navy Cross. Heyman’s gun crewmen were given commendations.

Within 24 hours of U-85’s sinking, the U.S. Navy Experimental Diving Unit arrived to conduct an initial survey of the new wreck and to see if U-85 could be refloated. Navy divers were transported to the wreck site via HMS Bedfordshire, a British trawler. Visibility was poor and impending bad weather kept divers from the wreck for the next five days.

On April 22, the fleet tug USS Kewaydin was assigned to the dive project as HMS Bedfordshire returned to convoy protection duty. The second diver down discovered an unexploded Mark VI depth charge along the starboard side of U-85. All dive operations were halted pending the destruction of the depth charge by the U.S. Navy Mine Disposal Unit.

On April 26, while the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Cuyahoga guarded USS Kewaydin, divers descended to U-85. The first diver down “made descending line fast to cleat on port side of submarine just forward of gun.” With Kewaydin tied to U-85, six dives were conducted. Divers noted the following: “(a) Submarine listed to starboard practically on its side—angle of deck with bottom about 80 degrees. (b) Forward on port side several stanchions torn away. Hull appears intact. (c) No other damage noted except clearing lines torn loose. (d) Forward gun swung forward and to port slightly elevated with tampon in place. (e) 20mm AA gun aft of conning tower in place, lines and wires fouled with it. (f) Conning tower apparently undamaged. (g) Upper conning tower hatch open with lubricating oil coming up through the hatch below.”

The diving report suggested U-85 was remarkably intact. The pressure hull was flooded as multiple hatches were open, but there was substantial integrity to the U-boat. The propellers were undamaged. The bow diving planes and aft diving planes were unscathed. The U.S. Navy wanted to raise U-85 only a week after its sinking.

The diving and salvage platform USS Falcon arrived on site. Over the course of 78 dives, Navy divers recovered the 20mm antiaircraft gun, the gun sights for the 88mm deck gun, elements from the gyro, and other instruments from the bridge. A Navy diver noted a wild boar with a rose in its mouth painted on the front of the conning tower.

Dive operations ended May 4, with the following recommendation by G. K. Mackenzie, Jr., commanding officer of USS Falcon: “Combining the information contained in the USS Roper report of action with that gained by divers, it is my opinion that this vessel was thoroughly and efficiently scuttled by her crew, and that successful salvage can be accomplished only by extensive pontooning operations.” The Navy never returned.

Situated east of the Oregon Inlet, U-85 rests at a depth of 100 feet and is considered a war grave for the 19 missing Kriegsmarine sailors who were never recovered after the sinking. U-85’s bow points southeast with a sharp 35-degree list to starboard. The 88mm deck gun is aimed toward the surface.

First-time WWII History contributor, Eric Petkovic lives in Huntingtown, Maryland.

Side note: After the war, interviews by the allies of both Raeder and Donitz, revealed that both had tried to tell Hitler that the Navy, as a whole, would not be ready for a war until 1943 at the earliest and preferably 1945. Both had remembered the strength of the British fleet at Jutland in June 1916. Hitler was unconvinced and the German fleet was essentially destroyed one by one by superior numbers in Allied fleets.

Along the same line as Mr. Link, after the Bismarck was sunk very early in the war, Adolf Hitler quickly and correctly realized the vulnerability of surface ships, especially battleships from airpower and submarines; therefore, from that time on, he hid the Tirpitz in a Norwegian fiord for the remainder of the war where it added very little to the German war effort other than being more of a potential threat to Allied convoys rather then doing any actual damage. Hitler had promised the Kriegsmarine an aircraft carrier but it never materialized due to Germany’s early starting WWII.