By Victor Kamenir

In the summer of 1875, the Christian Slavic populations of Bosnia and Herzegovina rose up in rebellion against their Muslim Ottoman Turkish rulers in response to high taxes and depredations by the local Turkish administration. What began as localized skirmishes flared into widespread revolt as unrest spread to neighboring Bulgaria. In June 1876, Serbia, quickly followed by Montenegro, declared war on Turkey in defense of its Christian brethren.

A no-quarter struggle raged across a wide swath of southeastern Europe, rife with atrocities on both sides. Especially prevalent was the carnage perpetrated by Ottoman irregulars, the Circassians and Bashi-Bazouks. The former were Muslim inhabitants of the Caucasus Mountains and Crimea who had resettled in various parts of the Ottoman Empire after their native lands came under Russian rule. The Bashi-Bazouks, literally meaning the “broken heads,” were Muslim bandits who turned up in large numbers wherever opportunities for plunder and murder presented themselves. These two groups were largely responsible for massacring of over 12,000 Christian civilians in Bulgaria. Serbia was saved from a similar fate only by a Russian ultimatum to Turkey, backed up by partial mobilization. Everywhere, the rebellion was brutally put down, but discontent smoldered just beneath the surface.

The Russian Empire, in the spirit of pan-Slavic unity, portrayed itself as the protector of the Ottomans’ Christian subjects. Russia had been demanding reforms and concessions from the Turks for almost two years. The Ottoman Empire, feeling itself secure after successful suppression of the insurgency, rejected Russian demands. Finally, on April 24, 1877, Russia declared war on Turkey. Bulgaria was to be the main theater of operations, separated from the Asian sideshow by the Turkish-controlled Black Sea. While the Russians enjoyed superior numbers overall, they were forced to detach sufficient forces to guard the northern shore of the Black Sea from Turkish incursions and station appropriate numbers in the Trans-Caucasus. This left the Russian field force in Bulgaria at slightly under 190,000 men.

Opposing them, the Turks numbered close to 200,000 men in the European theater of war. However, half that number was tied down guarding fortresses along the Danube River, leaving the other 100,000 men spread widely in the field. While the Russians enjoyed locally superior numbers, the Turks had the advantage of complete control of the Black Sea and had augmented their firepower by purchasing American-made rifles and German artillery.

The Danube River, flowing between Ottoman-occupied Bulgaria and Russian ally Romania, formed the natural border between the Russian and Turkish spheres of influence. Farther south, roughly dividing Bulgaria in half from west to east, the Balkan Mountains stretched to the Black Sea. Turkish plans called for forward static defense along the Danube River anchored by a system of strong fortresses and a flotilla of gunboats that cruised the river to prevent Russian landings. Failing that, the Turks planned to defend the natural barrier of the Balkans farther south.

Breaching the Balkan Mountains

During the first two months of the war, the Russians employed a successful strategy of mining the Danube and actively attacking Turkish vessels to neutralize the Ottoman flotilla and effect a river crossing near the town of Sistovo. On June 15, the Russians successfully crossed the Danube and established a strong beachhead, beating back Turkish counterattacks.

Original Russian plans called for rapid maneuver and deep penetration of Bulgaria through the Balkan Mountains followed by an advance to the Turkish capital of Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul). However, the Russian commander, Grand Duke Nikolai, the brother of Czar Alexander II, almost immediately deviated from plans and set about reducing Turkish fortresses and slowly moving inland. Meanwhile, a flying column under Maj. Gen. Joseph Gourko was dispatched to capture strategically important passes through the Balkan Mountains. The grand duke’s operations were greatly hindered by the presence of his august brother and Romanian Count Karl, soon to become Romanian King Karl I. Even though the czar did not take an active part in commanding the army, he and his large royal entourage felt free to dispense advice to the already overwhelmed grand duke.

As the Turks rushed men to establish the second line of defense south of the Balkan Mountains, they could not maintain a strong defense everywhere, and several passes through the mountains were left unguarded. An officer on Gourko’s staff, Prince Dmitry Tsertelev, had served as Russian military attaché at Adrianople (modern-day Edirne) shortly before the war. His knowledge of the neighboring country helped him to locate the undefended Khankoi Pass, in reality hardly more than a footpath.

For two days, undiscovered by the Turks, a force of 200 Russian pioneers labored to improve the worst section of the trail to allow passage of cavalry and mountain guns. While they worked, Tsertelev, in the disguise of a local shepherd, scouted the south end of the pass and pronounced it free of Turks. Even after improvements made by Russian pioneers, however, it took Gourko’s force three days to navigate the narrow passage. The footing on the steep slopes was too treacherous for the artillery horses to haul the guns uphill. Instead, a company of infantrymen laboriously dragged the guns upward, step by perilous step. Gourko’s commissary officers paid cash to local peasants, and the exhausted Russian soldiers were treated to welcome hot food every night.

The Shipka Pass

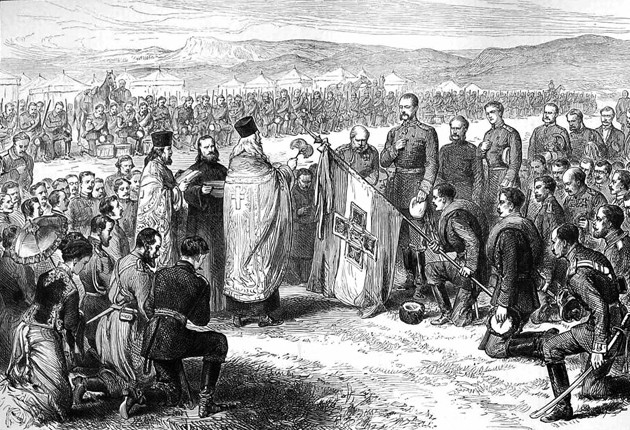

After clearing Khankoi Pass, the 11,000 men of Gourko’s detachment moved into the Tundja Valley. The force consisted of three battalions of the 4th Rifle Brigade, three regiments of regular Russian cavalry, four Cossack regiments, four horse and one mountain artillery batteries, and six battalions of militia from the Bulgarian Legion. Brushing aside several Turkish battalions sent against him from Shipka and Kazanlak, Gourko fanned out his Cossacks across the countryside to confuse Turkish commanders as to his true intentions. Leaving behind a small detachment to guard the southern end of Khankoi Pass, Gourko cut west along the mountains, arriving behind the Turkish defensive works at the Shipka Pass.

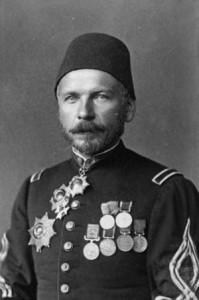

Turkish commander Reuf Pasha was tasked with defending the Balkan Mountains from Shipka to Sliven. His force consisted of 34 battalions of regular infantry, or Nizams, three artillery batteries, three regular cavalry squadrons, 1,000 mounted Circassians, and several thousand Bashi-Bazouks irregulars—in all, a force of some 22,000 men. There were no additional Turkish troops closer than Adrianople, but a railhead at Nova Zagora would permit rapid deployment of reinforcements.

Strategically important, Shipka Pass presented the most expedient passage for the main Russian army into the heart of Bulgaria and on to Adrianople, the second largest city of the Ottoman Empire. However, as described by British correspondent Archibald Forbes: “The Shipka Pass is no pass at all in the proper sense of the term. There is no gorge, no defile; there is no spot where 300 men could make a new Thermopylae; no deep-scored trench as in the Khyber Pass, where an army might be annihilated without coming to grips with its adversary. It has its name simply because at this point there happens to be a section of the Balkans of less than the average height, the surface of which, from the Yantra Valley on the north to the Tundja Valley on the south, is sufficiently continuous, although having an extremely broken and serrated contour, to afford a foothold for a practicable track, for the Balkans generally present a wild jumble of mountain and glen, neither having any continuity. Under such circumstances, such a crossing place as the Shipka Pass affords is a godsend, although under other circumstances a road over it would be regarded as impossible.”

The Turkish Retreat

Gourko’s orders required him to act in concert with Maj. Gen. Prince Nikolai Mirsky’s 9th Infantry Division, which was approaching Shipka Pass from the north. However, Gourko was delayed by having to force aside Turkish detachments and arrived at Shipka Pass one day late, on July 18. Along the way, he captured a village near the small town of Kazanlak.

Even without Gourko’s support, Mirsky pressed his attack on July 17 with the 36th (Orlovski) Infantry Regiment and some Cossacks, a force of more than 2,000 men and six guns. He was facing the Turkish force of 4,000 regular infantry, some Bashi-Bazouks, and 12 guns. Mirsky’s attack on the main Turkish positions failed, but secondary attacks captured mountains on both sides of the pass. The next day, July 18, as Mirsky rested his force, Gourko attacked from the south. He sent forward two battalions of riflemen and some dismounted Cossacks, but their attack failed as well; they suffered roughly 150 killed and wounded.

Despite beating back two Russian attacks, Turkish commanders at Shipka Pass realized that they could not withstand a coordinated offensive from both north and south. On the morning of July 19, while pretending to consider the terms of surrender, the Turkish garrison slipped away to the west in small groups, leaving behind a large cache of explosives, ammunition, and artillery.

While waiting for the Turkish response, Gourko sent forward several groups of hospital orderlies to search for Russian wounded who had not been recovered the previous day. Eventually, as Russian pickets from north and south cautiously probed inward, they found the Turkish positions abandoned. An even grimmer discovery awaited them there, as Colonel Nikolai Epanchin described in his book: “Not far off lay the mutilated bodies of our riflemen, and among them hospital orderlies with the Red Cross on their arms. These bodies presented a terrible sight: half naked and with fingers cut off, with the knees turned outwards, and the soles with strips of skin cut off.”

The Plan to Retake the Pass

The capture of Shipka Pass caused a great stir in the Turkish military establishment. The senior Ottoman field commander, Abdul Kerim, was sacked and replaced with another commander, Mehemet Ali Pasha. A frantic dispatch from the Turkish chancellery read: “In consequence of the ground covered by the enemy, the empire is between life and death.” Another high-ranking Ottoman officer, Suleiman Pasha, was recalled from Montenegro with 20,000 veteran troops.

In the meantime, the main Russian army was held up by a determined Turkish defense of the strategically important town of Plevna in northern Bulgaria. Instead of the envisioned campaign of rapid maneuver, operations became static. Other than Gourko’s force, no additional Russian troops crossed the Balkan Mountains into southern Bulgaria. Lt. Gen. Feodor Radetsky, commander of the 8th Corps, received the task of screening the northern rim of the Balkan Mountains along a sector of over 60 miles with his base at Tarnovo. Gourko’s force was subordinated to Radetsky.

After garrisoning the Shipka Pass with one Russian infantry regiment and one battalion from the Bulgarian Legion, Gourko continued probing the area south of Kazanlak, using that town as his base of operations. On July 29, four battalions of the Bulgarian Legion were on an intelligence-gathering expedition to Stara Zagora. In a sharp engagement with superior numbers of Suleiman Pasha’s advance guard, the Bulgarians fought bravely but were forced to fall back after suffering heavy casualties. The Turks did not press hard after them, falling instead on the Christian population of Stara Zagora, burning down most of the town and massacring approximately 8,000 of its 18,000 Bulgarian residents.

As Suleiman Pasha’s force arrived at Stara Zagora, it continued to grow, taking in outlying detachments and reinforcements. In the face of overwhelming numbers, Gourko was forced to withdraw north through Khankoi Pass. He left behind a strong rear guard to hold the entrance to the defile and sent the five Bulgarian battalions to bolster the garrison at Shipka Pass.

The Russians Fortify Their Position

Major General Valerian Dzerzhinsky, commander of the 2nd Brigade, 9th Infantry Division, took charge of Shipka Pass defenses. His command consisted of five battalions of Bulgarian militiamen, the Russian 36th Regiment, five Cossack companies, and 29 guns—some 5,500 men in all. Shipka Pass was not a true road, but a trail running across a ridge of the Balkan Mountains at an altitude of 4,500 feet. Higher ridges ran parallel on both the east and west sides, separated from the pass by deep and thickly forested ravines that could only be navigated with great difficulty.

The 4,900-foot-high Bald Mountain dominated the pass on the west, while the Demir-Tepe and Maly-Bedek Mountains held similar overwatch positions on the east. Vegetation at Shipka Pass stopped roughly 600 feet from the top of the ridge, and there was no natural shelter anywhere within the Russian positions, leaving them open to crossfire from neighboring ridges. The pass itself was rarely wider than 180 feet, further hindering Russian preparation of proper defenses. The deeply forested ravines allowed the enemy to approach without being observed or fired upon.

Since capturing the pass, Russian troops had been busy improving their defensive positions. Captured Turkish entrenchments that had been facing north had to be modified to face south. New infantry trenches needed to be dug, but the Russian units at Shipka did not possess engineering tools and the soldiers had to dig into the rocky terrain with their bare hands and canteen cups. Since hardly any trench was deep enough to shelter a man, abundant rocks provided handy material to build up breastworks. Large quantities of Turkish gunpowder had been captured at the pass, and Russian engineers buried explosive charges at the most likely avenues of approach.

Russian positions were divided into two sections dictated by the availability or lack of suitable flat ground. The sections were joined by a narrow strip of land that contained the former Turkish guardhouse and barracks. The forward position included the Steel, Big, and Little Batteries, emplaced on a small plateau called Mount St. Nicholas. The Steel Battery faced the Demir-Tepe Mountain, while the other two faced south and southwest, respectively. Infantry trenches encircled the batteries. The main position, to the north of the forward one, included the Central and Round Batteries facing Bald Mountain and was protected by infantry trenches. An aid station was set up in the old Turkish barracks building.

Shipka Pass lacked creature comforts. There was no natural water source at the top of the ridge, and most food had to be cooked at the bottom of the pass and brought up by hand. To ease the living conditions of his troops, Dzerzhinsky kept the bulk of his men in Shipka village, leaving only a skeleton garrison at the pass. When Dzerzhinsky’s forward pickets spotted the advance elements of Suleiman Pasha’s army on August 18, he withdrew his whole force into the pass.

With an attack imminent, Dzerzhinsky placed one battalion from the 36th Regiment and four Bulgarian militia companies in the Mount St. Nicholas position. Another Russian battalion and three Bulgarian units went into the main position, with the last Russian battalion and two more Bulgarian battalions comprising the reserve on the isthmus between both positions.

Russian vs Turkish Artillery

After brushing aside the Bulgarians at Stara Zagora, Suleiman Pasha steadily pressed forward, arriving on August 19 at Shipka village. By then, his force had swelled to almost 30,000 men. One of the officers under Suleiman’s command was Khulusi Pasha, the same officer who had abandoned Shipka Pass to Gourko in July. Intimately familiar with the local terrain, Khulusi Pasha advised his superior to concentrate his main efforts on the Russian left, where he believed the enemy would be most vulnerable. Suleiman Pasha concurred.

At dawn on August 21, Turkish forces began advancing on the forward Russian positions. Once clear of the woods, Turkish soldiers slowly climbed the steep southern slopes, heading for Mount St. Nicholas. Russian and Bulgarian defenders opened up spirited rifle and artillery fire on them, inflicting heavy casualties. A Turkish battery ascended Maly-Bedek Mountain and began pouring fire down onto Russian positions.

More Turkish troops entered the fray from the east, coming down Demir-Tepe Mountain and climbing Mount St. Nicholas. The Steel Battery was effective in counterbattery fire against Maly-Bedek and Demir-Tepe, and the Big Battery mowed down advancing Turkish lines in front of it. During the day, the 35th (Bryanski) Regiment arrived to bolster Russian defenders. First Lieutenant Francis Greene, the U.S. military attaché at Russian headquarters, was present that day at Shipka Pass and noted: “[The Turks] attacked with the utmost desperation, but were as desperately received.” When the fighting finally ended for the night, the Turks remained within 100 yards of the Russian positions.

The next day, August 22, Turkish commanders reorganized their units and evaluated the results of the previous day’s fighting. More Turkish guns were brought up and placed to face the Russians from west, south, and east. A force of dismounted Circassians climbed down the slopes east of the Russian positions and kept the road to Gabrovo under fire. Wrote Greene: “Throughout this day a continuous fire of artillery and infantry was kept up, but the Turks made no serious attacks; a few guns were dismounted on both sides, but a far more serious danger was threatening the Russians in the lack of artillery ammunition, which was nearly exhausted. Both parties worked all day at repairing their batteries, and the Turks at covering their advanced positions by shelter-trenches.”

Holding the Position With Rocks and Boulders

On August 23, Suleiman Pasha launched a major assault on Russian positions, coming at them from three directions. Despite galling Russian fire, Turkish soldiers bravely climbed the steep slopes. The Russians set off explosives emplaced at Mount St. Nicholas and in front of Central Battery, causing great loss of life among the advancing Turks. Still, the Ottoman regulars, the Nizams, reached Russian trenches in several places, and fighting became hand to hand. A body of Turks broke through to the Round Battery, and many Russian gunners, including their colonel, died where they stood defending their guns. Only a furious bayonet charge by reserve companies of the Orlovski Regiment restored the situation. Another group of Turks broke through to the aid station, where Dr. Konstantin Vyazenkov led lightly wounded Russian soldiers in a counterattack.

There was no shortage of bravery that day. The Turkish soldiers hurled themselves time and time again at the Russian positions despite terrible casualties. The Russians and Bulgarians fired until some men ran out of ammunition, after which they resorted to rolling boulders down the slope, throwing rocks, and even hurling Turkish corpses at the attackers.

The critical stage of the fighting came around 3 pm, when a large Turkish force attacking from Bald Mountain overran the Central Battery and the Russian defenders began edging back. The Bryanski Regiment defending the position lost most of its officers, and more and more soldiers began to slip down the road to Gabrovo. Greene remembered: “Taking a few non-commissioned officers, Colonel Lipinsky, commanding this part of the field, went back to the road, expostulated, reasoned, threatened, and drove these men back to the positions on the Center Hill. From there they delivered their fire in volleys upon the Turks in their rear, who were just beginning to climb the slope toward the road. Stunned by this sudden reception, the Turks wavered a little.”

Help arrived in the nick of time. A force of roughly 200 riflemen from the 4th Rifle Brigade arrived doubled up on Cossack horses. They immediately counterattacked with bayonets, retaking the Central Battery. Soon, the rest of the 4th Rifle Brigade arrived, led by Radetsky himself, and restored the situation. During the night, the four regiments of the Russian 14th Infantry Division under Maj. Gen. Mikhail Dragomirov reached Shipka Pass. Radetsky felt himself sufficiently strong to attempt to take Bald Mountain the next morning.

Before Radetsky could put his plan into motion, the Turks attacked the Russian positions. During one of the Turkish attacks, Dragomirov was hit by a bullet in the knee, which shattered his kneecap. The stoic general remained at his post until the attack was repelled.

Concluding the First Battle for Shipka Pass

After repulsing initial Turkish assaults, Radetsky sent two battalions forward in an attempt to take Bald Mountain. Now it was the Russians’ turn to climb the steep slopes under a hail of bullets and shells. Closing on one Turkish redoubt, they discovered that it was protected by an abatis of felled trees, creating a nightmarish tangle of branches and brushwood. The first Russian company attempting to scale the redoubt was decimated. After suffering heavy casualties, the Russian battalions fell back without achieving their goal.

The next day the Russians repeated their attempts to take Bald Mountain. Unable to take the whole mountain, they pushed the Turks off a height called Wooded Hill. During this fight, Dzerzhinsky was shot through both lungs. He was taken down to Grabovo village, where he died shortly afterward.

On August 26, the Turks launched several attacks to retake Wooded Hill. While the Russians held, casualties among its defenders, the 35th Regiment from Dzerzhinsky’s brigade, were so heavy that Radetsky ordered the hill abandoned. With this action, the first stage of the battle for Shipka Pass ended.

Heavy Casualties on Both Sides

During the six days of fighting, the Russian and Bulgarian defenders lost almost 3,500 men killed or wounded, including two generals. The Bulgarian portion of the allied losses came to 267 men killed and 282 wounded. With the fighting over for at least a short period, Radetsky withdrew the depleted Orlovski and Bryanski Regiments and the Bulgarian battalions from the line and quartered them in and around Gabrovo. Residents of Gabrovo earned special thanks from the defenders of Shipka Pass, daily bringing up food and water to its defenders, often under fire, and evacuating the wounded in their ox-drawn carts. With a chance to catch their breath, the Russian defenders set about fixing and improving their positions. Thousands of dead bodies strewn around in the August heat and the lack of proper latrine facilities created unsanitary conditions on the ridge that required immediate attention.

Conditions on the Turkish side were poor as well. The Ottoman losses during the same period came to almost 10,000 men killed or wounded. Especially dire was the condition of the Turkish wounded, who were forced to rely on the Ottoman military medical system, which was woefully not up to the task. As a testament to the low quality of Ottoman military medicine, wounded Turkish officers preferred to be treated by British volunteer doctors of the English Societies of the Red Crescent.

A Second Attempt to Take the Pass

After losing almost a third of his force, Suleiman Pasha spent the next three weeks reorganizing his units and pulling in any reinforcements he could get, including a division of Egyptian troops. His force was badly needed in northern Bulgaria, and Suleiman’s nominal superior, Mehemet Ali Pasha, ordered him to proceed to Shumen. However, the military command structure of the Ottoman Empire was rife with petty personal feuds, especially between natural-born Turkish officers like Suleiman Pasha and expatriate Europeans like Mehemet Ali, who was born Jules Detroit in Germany of French Huguenot ancestry. Suleiman Pasha chose to ignore his instructions and remained in front of Shipka Pass.

On September 17, Suleiman Pasha launched another assault on Mount St. Nicholas. It had been raining steadily since the beginning of September, and Turkish troops climbing the steep slopes had to deal with slippery and unsteady footing. Still, they came on steadily and even came to grips with the Russians and captured the lower trenches but could not reach the top of the mountain. A strong Russian counterattack drove them back at bayonet point. Throughout the day, the Turks attempted several more attacks at other sectors of the Russian defenses but were unsuccessful everywhere.

The battle was costly. After losing another 3,000 men, Suleiman Pasha did not attempt any more assaults on Shipka Pass. Russian losses were roughly half the Turkish losses. With the war going badly for the Ottoman Empire, Mehemet Ali Pasha was sacked and Suleiman Pasha was appointed in his place, departing for northeastern Bulgaria. Another former German, Veissel Pasha, was appointed in his place to keep the Russians bottled up at Shipka Pass.

“Everything is Calm at Shipka”

But the epic Russian defense was not over. The first snow fell on September 20, and the famous “Shipka Sitting” began. Battle-weary men of the 9th and 14th Infantry Divisions and General Nikolai Stoletov’s Bulgarian Legion were withdrawn. They were replaced with fresh regiments from the 24th, 93rd, 94th and 95th Divisions.

The weather steadily continued to worsen, replete with strong winds and deep snows. The living conditions of the Russian troops on the bare mountaintop were horrible. The shallow dugouts quickly became packed with snow, and the men had to spend almost all of their time outside, exposed to the elements. There was no chance to start a fire; coal had to be brought up from Gabrovo, 10 miles away. Often men would not sleep, walking huddled together all night to keep warm.

Sentries froze to death on duty; a man who fell down could be covered by snow in minutes. Sometimes men were blown off the mountain by strong winds. Overcoats became stiff with ice and would break instead of folding. The 24th Division was decimated by illness. By December 17, the Irkutski Regiment had 1,042 men sick, with another 1,393 in Eniseiski—over one-third of each unit. Radetsky and his staff stoically shared all deprivations with their men. His regular dispatches, which soon became famous throughout all Russia, assured: “Everything is calm at Shipka.”

Halted At San Stefano

However, change was coming. The Turkish defenders of Plevna finally surrendered on December 20, and Russian troops were freed up to relieve Radetsky’s men. By December 24, the worn-out men of the 24th Division came down the mountain for good. Radetsky remained at Shipka Pass and took command of the relieving units.

With the fall of Plevna, the main Russian army renewed its general offensive. Once again, Gourko led men through the Balkan Mountain passes, this time to the west of Shipka. Navigating the passes through the deep snow, Gourko’s 70,000 troops entered Sofia, the Bulgarian capital, on January 4, 1878. He then swung his force east to relieve Shipka. Radetsky received additional forces and orders to attack, timing his operations to the arrival of Gourko’s force.

From January 5-9, Gourko and Radetsky trapped the army of Veissel Pasha at Sheynovo, one mile from the village of Shipka. Now enjoying superior numbers, roughly 110,000 Russians against 35,000 Turks, the Russians defeated Veissel Pasha, taking prisoner some 30,000 of his men.

With the removal of Veissel Pasha’s force, no Ottoman troops remained in the field to oppose the Russians. Gourko pressed on to Philippoupolis (modern-day Plovdiv) and Adrianople in quick succession. As the victorious Russian army continued advancing on the Ottoman capital of Constantinople, the Western powers, led by Germany and Great Britain, became concerned about the Russians gaining the upper hand in southeastern Europe. Under direct threat of Western intervention, the Russian army halted on February 2 at San Stefano (modern-day Yesilköy), just west of Constantinople.

The Beginning of the Balkan Wars

Under the terms of the Treaty of San Stefano and the follow-up Treaty of Berlin, Turkey agreed to pay war reparations and ceded territory to Russia. Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro received their independence from Turkey, and Bulgaria became autonomous. The Ottoman Empire was finished as a power player in Europe. Suleiman Pasha was tried by an Ottoman military tribunal for incompetence. He was stripped of his rank and privileges and exiled, dying in Baghdad in 1892. Mehemet Ali Pasha was exiled as well, dying six years later.

Losses were heavy on both sides, roughly 120,000 suffered by each antagonist. As was common in that era, almost two-thirds of the deaths resulted from noncombat illnesses. Bulgaria suffered approximately 15,000 soldiers killed and wounded and more than 50,000 civilians massacred by the Turks.

The consequences of the Treaty of Berlin were far reaching. In 1912, the Balkan League (Serbia, Greece, Montenegro, and Bulgaria) fought against the Ottoman Empire, resulting in more territory reshuffling. The next year, not happy with its gains, Bulgaria attacked its former allies Greece and Serbia. Defeated, Bulgaria lost some of the territory it gained in the First Balkan War in 1912. Despite the brotherhood displayed by men of Russia and Bulgaria during the five-month Shipka Pass campaign, the two countries did not become close. Preferring to operate in the German sphere of influence, Bulgaria fought on the German side in both world wars, and even today relations remain lukewarm between the two neighboring countries.

Indirectly, the Treaty of Berlin encouraged Austria-Hungary to annex Bosnia in 1908, which led directly to World War I six years later. In many ways, the world has never recovered from that pointless conflagration.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments