By David A. Norris

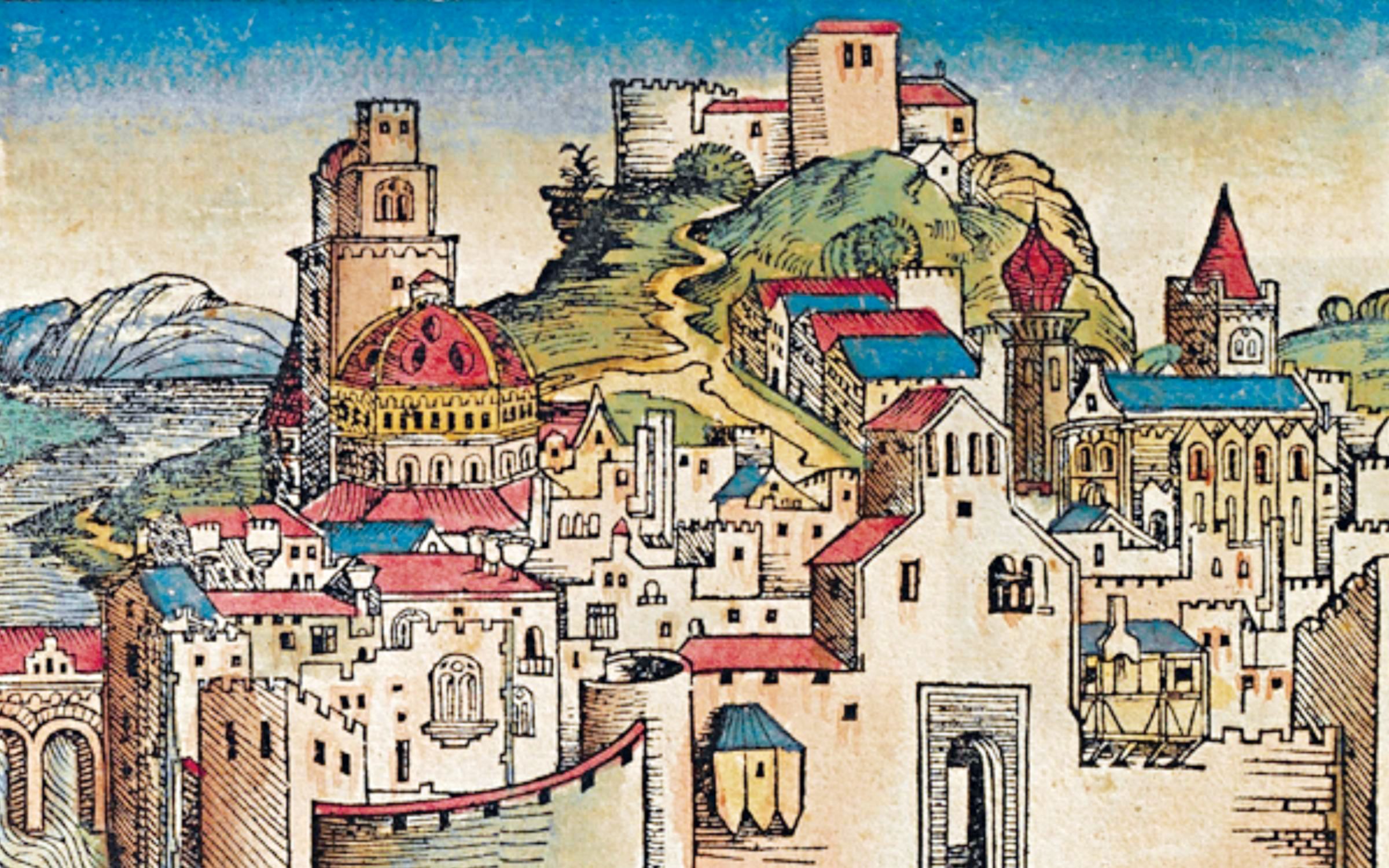

According to legend, Carthage was founded by Dido, daughter of the king of the Phoenician city of Tyre. Fleeing after her brother Pygmalion killed her husband, Dido made her way to the North African coast where she founded a new city on the Hill of Byrsa, on land purchased from a local chieftain. Around the hill grew the great city of Carthage that rose to contest Rome for control of the western Mediterranean. Centuries later, in 149 BCE, Carthage was only a shattered remnant of its past glory. Her colonies were conquered by Rome and hostile neighboring kingdoms; her army and navy were destroyed; and the very city of Carthage was a panorama of blazing ruins. Only the Hill of Byrsa held out against Rome—with the last citizens who preferred death to life as Roman slaves.

The Third Punic War was the last of three clashes between the growing western Mediterranean powers of Rome and Carthage. The First Punic War lasted 23 years between 264-241 BCE, and the 17-year Second Punic War ground on from 218-201 BCE In the second war, Carthage was led by the legendary Hannibal. Despite bringing a contingent of war elephants over the Alps into Italy, and crushing the Roman Army in the Battle of Cannae, the war ended with Rome victorious over the Carthaginians. A shaky peace stretched out for three decades.

Carthage stood on a peninsula jutting into the Mediterranean from the mainland of what is now Tunisia. Its naval and maritime power aroused the suspicion and hostility of Rome, which was cementing control of the Italian peninsula and spreading to other western Mediterranean lands. The Romans called the Phoenicians the Poeni, from which we get the word Punic.

Rome and Carthage were each republics that grew from large, powerful capital cities into sprawling empires. A major difference was their attitude toward their armies and navies. Rome depended on its massive army, drawn from its property-owning male citizenry, and its navy was secondary in importance. Carthage depended on its maritime strength and a large navy. So much of Carthage’s manpower went into the fleet that it had to fill its army with mercenaries and colonial soldiers.

By 264 BCE, Carthage controlled lands far beyond the city and the surrounding territory, to include coastal strips and enclaves of modern Morocco, Algeria, and Libya; the southern Iberian Peninsula (Spain); the Balearic Islands; Corsica; and parts of Sardinia and Sicily.

The Second Punic War ended with Carthage defeated and shorn of most of its empire, and its military power. The Romans allowed their enemy only 10 war vessels, and forbade them to keep war elephants. Indeed, Rome prohibited Carthage from taking up arms against anyone.

In the uncertain interval of peace after the end of the Second Punic War, a son was born to the noted Roman military commander Amelius Paullus. This son, first known to history as Scipio Aemilianus, was only 17 when he first went to war. The young Scipio accompanied his father, who earned considerable distinction in Rome by conquering Macedonia in the Third Macedonian War. After Amelius Paullus divorced his wife, as the family fractured, the young man was adopted by Publius Scipio. This adoptive father was the son of the famous Scipio Africanus, who defeated Hannibal’s formidable Carthaginian forces in the Second Punic War. Young Scipio gained further military and political experience in Spain. He steadily worked his way up the cursus honorarium, the system that drew young men of senatorial rank through a course of steadily rising posts, alternating between military and civilian jobs in Rome and abroad.

Rome still glowed with the glory of their victory, but worries about Carthage smoldered. Carthage’s military power was devastated by the previous wars, but its trade flourished enough to concern the leaders of Rome. The statesman Cato the Elder led the political opposition to Carthage. He famously ended his speeches in the Senate, on whatever topic, with the grim warning: “Carthage must be destroyed!” (Carthago delenda est).

After Carthage’s defeat, all of their North African territories save the region around their capital were part of the kingdom of Numidia. Masinissa, king of Numidia, had once supported Carthage but switched his allegiance to Rome in 206 BCE. Masinissa and his Numidian cavalry helped the elder Scipio defeat Hannibal at the Battle of Zama. Since that time, Masinissa took advantage of Rome’s good will. Shielded by the peace treaty, he nibbled away at Carthage’s remaining land.

In 150 BCE, Carthaginian patriots could no longer abide the constant aggressions of the Numidians and declared war on them. A general known as Hasdrubal the Boetharch (“boetharch” was a high military or civil rank among the Carthaginians) led an unsuccessful attack on Numidia. War with Numidia, though, threatened a war with Rome. Carthage’s leaders realized they had gone too far. They sent envoys to Rome to negotiate. The leaders of the patriot faction, Hasdrubal and Carthalo, were sentenced to death.

As tensions rose, the city of Utica informed the Romans that they had switched their allegiance from Carthage to Rome. Utica’s betrayal ended centuries of political alliance and cultural ties; this port had been the earliest Phoenician colony in North Africa. At a stroke, the Romans gained even better odds in the impending clash, and secured a safe landing place for their army that was only 20 miles north of Carthage.

Rome then declared war—to be carried out by the two consuls then in office, Manius Manilius and Lucius Marcius Censorinus. Since the end of the ancient monarchy in 509 BCE, Rome was ruled by two elected consuls chosen each year. Although they had some executive functions such as presiding over the senate, the chief duty of the consuls was command of the Roman military.

With the two consuls, 80,000 Roman troops disembarked at Utica in 149 BCE. To mollify the Romans, Carthage agreed to make amends by sending 300 hostages to Sicily. The hostages, children taken from the most prominent families, were not enough for the Romans. Carthage was now under Roman “protection,” and had no need of weapons. So, Rome’s envoys demanded the surrender of all weapons and military equipment.

Some 200,000 sets of armor and stands of weapons, as well as 2,000 catapults and numerous projectiles, were handed over to Rome. The historian Arrian recorded, “It was a remarkable and unparalleled spectacle to behold the vast number of loaded wagons which the enemy themselves brought in”.

But the elite hostages, along with all the weapons and military equipment from their old enemy was not enough to assuage the enmity of the Romans. Addressing a delegation of Carthaginian ambassadors and senators, Censorinus decreed that the price of peace was the abandonment of the city of Carthage. Its citizens must find a new site for their city that was at least 10 miles from the sea. Unable to survive being cut off from the sea, Carthage had no choice but to go to war with Rome a third and, ultimately, final time.

The members of the Carthaginian delegation faced not only the ruin of their city, but their personal doom as well. Some so feared the reaction of the population that they stayed in the Roman camp and never returned home. Others were mobbed at the gates of the city, their lives only spared so they could make a formal report to the senate of Carthage. The senate received the news in shocked silence before giving way to “a loud and mournful outcry,” according to the Roman historian Appian.

At the terrible sound arising from the senate, citizens burst in and learned the devastating news. In “a scene of indescribable fury and madness,” wrote Appian, “… Some fell upon those senators who had advised giving the hostages and tore them in pieces, considering them the ones who had led them into the trap. Others treated in a similar way those who had favored giving up the arms.”

On the same day the ambassadors returned from the Roman camp, the senate of Carthage declared war. All slaves were freed. Couriers went to tell the condemned patriot leader Hasdrubal that his death sentence was remitted, and offered him the military command of the city. Hasdrubal the Boetharch had gathered soldiers to march against Carthage, but he accepted command and threw in his lot with his countrymen. The city’s gates swung shut. With their catapults gone, the townspeople carried stones to the ramparts to drop upon the Romans when they surged under the city walls.

The Second Punic War had already left Carthage much less powerful than it had been in the previous wars with Rome. Most of their colonies and possessions were gone, eliminating anything that might delay or distract Rome from concentrating on the remaining patch of territory around the capital itself.Carthage’s available manpower had mostly gone into its navy, and the armies had depended on mercenaries. Now, far fewer soldiers could be found in their shrunken territories.

Nonetheless, the people of Carthage made an incredible effort to defend their city. Makeshift workshops, some of them set up in temples, immediately opened. Women joined men in running the workshops, which operated night and day without cease. Lead roofing was seized, and whatever iron could be scrounged was melted down for new weapons. Appian noted that “Each day they made 100 shields, 300 swords, 1,000 missiles for catapults, 500 darts and javelins, and as many catapults as they could.” He also wrote the women cut off their long hair, to make ropes for the new catapults.

Expecting no resistance, the overconfident Censorinus and Manilius did not stir from their camps for some time. When finally the Romans did advance to receive the surrender of Carthage, they found instead closed gates and walls bristling with soldiers and new weapons.

The great city stood on the southeastern edge of a peninsula that jutted eastward into the Gulf of Tunis and the Mediterranean Sea. With the sea to its east, Carthage was nearly surrounded by water. To the southwest was a salt lake, (Stagnum Marinum) now known as the Lake of Tunis; to the northwest, another body of salt water called the Salinae.

A triple layer of walls ran from north to south between the lakes, protecting the city’s western side. A single stone wall ran east from the northern edge of the western wall, then turned south toward the city, surrounding a suburban area called Megara. Much of the district was given over to gardens and orchards, divided by low stone fences and hedges. Steep cliffs facing the sea gave extra protection to the Megara.

The city itself, south of Megara on the southeastern portion of the fortified peninsula, was protected on the land approaches from the north by a formidable wall, with the outer face being 45 feet high and up to 7 feet thick. Stone towers rose every 200 feet along the perimeter. Sea walls protected the city from attacks via the Mediterranean.

Two harbors had been built in the southeastern part of the city. The oblong mercantile harbor ran north to south just under 1,400 feet, and was 1,066 feet wide. There was only one narrow entrance, in the southeastern corner. North of the mercantile harbor was the naval harbor. A vast circle, 1,066 feet in diameter, the naval harbor surrounded a round island with a naval headquarters. There was room for 220 ships along the wharves lining the circular shore. There was only one way to get into the naval harbor, by an opening to the south that was accessible only through the mercantile harbor. The openings to both harbors could be closed with massive chains. Stone walls around the harbor area offered further protection.

The Roman army launched attacks on the city walls. Manilius hurled his men against the western walls that crossed the isthmus. His plan was to fill in a section of ditch in front of the defenses, then cross the parapet of the outer layer and climb the main wall with ladders. Expecting to break through into the weakened city, they were thrown back by the surprisingly sharp resistance.

There was only one obvious weak point in the defenses of Carthage. The southwestern corner of the city touched a narrow stretch of land called the Taenia, which separated the Lake of Tunis from the Mediterranean Sea. Taenia was the one angle of the city that could be attacked by land or sea, but the fortifications were not as formidable as those on the north.

Censorinus had his eye upon this Achilles’ heel of the city. He squeezed his troops onto the narrow shelf of land before the walls. They pushed ladders against the stone facing, while others tried to climb up the sea walls from ladders placed on Roman ships. This attack was also foiled.

Knowing they now faced a long siege, and that Hasdrubal the Boetharch roamed free with a sizable army, the consuls paused to fortify their camps. While Manilius waited outside the western wall, Censorinus brought the Roman ships into the Lake of Tunis. The latter commander sent an expedition to cut timber for the construction of siege engines. The troops were then attacked by Carthaginian light cavalry under Hamilcar Phameas, and the Romans lost 500 legionnaires.

Despite the setback, the troops brought back the timber needed. To have more land to assemble their attack, the Romans filled in a great stretch of Lake of Tunis with sand and rock. On the newly claimed ground, engineers constructed two gigantic battering rams. Each of the massive rams required 6,000 men to operate. One of the rams knocked a gap into the wall, but the garrison managed to blunt a Roman assault and hold off the enemy until nightfall.

The Carthaginians rushed to mend the gap in the wall. Worried that the work could not be completed by daybreak, their commanders sent out a raiding party that surprised the Romans. Some raiders carried torches that they used to set fire to the siege machines. While a Roman counterattack saved the machines from completely burning, the rams were damaged enough to make them useless for some time.

The breach had not yet been sealed by first light, allowing Roman soldiers to rush through the gap, pouring into an open area “where the Carthaginians had stationed armed men in front and others in the rear provided only with stones and clubs, and many others on the roofs of the neighboring houses, all in readiness to meet the invaders.”

Not all the Romans fell into the trap set by the defenders. Scipio Aemilianus, who had risen to the rank of tribune, was suspicious and held his men back. The attacking legionnaires were driven out through the breach, with Carthaginians in hot pursuit. Scipio sent his men into the fray and saved the assault party from slaughter. His cool thinking in averting a minor disaster brought him to the notice of the commanders.

After the attacks on the Taenia stalled, sickness broke out in the Roman camps. Censorinus, to preserve the health of his men, moved his troops out of their camps onto ships. Seeking purer air, they sailed from the Lake of Tunis into the sea.

As the Romans floated on the sea, the Carthaginians obtained some small vessels, which they filled with flammable material. When the wind blew away from the city walls toward the Roman fleet, the improvised fire ships were doused with pitch and brimstone and set on fire. The Carthaginians then raised the sails and sent the boats toward the Roman fleet, causing great destruction.

Next came a surprise attack on the camp of Manilius. Under cover of darkness, armed Carthaginians slipped out of the city, accompanied by men carrying planks. The bearers dropped the planks to form bridges across the ditches around the Roman camp, and the soldiers clambered across them and began hacking down the palisade.

Though most of Manilius’ camp was thrown into chaos, Scipio Aemilianus stayed characteristically calm. Thinking quickly, he and his cavalry rode out of the camp through a gate not yet under assault. When the horsemen loomed out of the darkness, the Carthaginians broke off the attack and rushed back to the safety of their walls. For the second time, this junior officer had saved the army from a potential reverse.

Manilius, concerned with his supply lines, built a fort by the sea where ships could land under protection. Tribunes scoured the countryside for food, forage, and wood. Phameas, still in charge of the enemy’s light cavalry, harassed the foraging parties. His men rode “small but swift horses that lived on grass when they could find nothing else.” Finding cover in thickets and ravines, the horsemen waited for favorable moments to fall upon the Romans with surprise attacks. Scipio Aemilianus, though, took precautions. His foragers set to work only when surrounded by lines of armed infantry and mounted men. Scouting parties searched the surrounding countryside, on the lookout for Phameas. Thus, Scipio’s foraging expeditions were always successful, with minimal casualties.

Censorinus returned to Rome, leaving Manilius to continue operations. Hasdrubal and Phameas still maintained large numbers of infantry and cavalry in the field. Masinissa refused when the Romans asked for help. A breach between the Numidians and Rome was averted by the death of the now elderly Masinissa. Cato the Elder, who lived to see the start of the war he’d done much to start, also died about this time.

Hasdrubal had his main army at Nepheris, about 20 miles south of Carthage. With a secure base, Carthaginian foot and horse soldiers raided Roman supply lines, and saw that food and supplies got into the besieged city. Manilius decided to attack Nepheris. Scipio, knowing that the Romans had to march through rugged terrain of mountainous crags, ravines, and thickets to attack an enemy force holding high ground, advised against the plan. Other tribunes scoffed at Scipio’s caution, thinking his attitude showed more cowardice than prudence.

Manilius went ahead with the attack and, after heavy fighting with little success, realized that Scipio had been right and ordered a withdrawal. The Roman retreat stalled at a river, where steep banks and difficult fords slowed their passage. Hasdrubal launched a deadly assault on the vulnerable Roman column, inflicting severe losses. Among the dead were three of the tribunes who had ridiculed the caution of Scipio, and urged Manilius to make the attack. Scipio again led his horsemen to hold off the enemy, and allowed the infantry to get across the river.

Although Scipio enabled most of the Roman soldiers to withdraw safely, four cohorts of legionnaires were left stranded on the enemy side of the river. The four detachments were surrounded by Hasdrubal’s troops. Some of Manilius’ officers reluctantly urged the consul to leave them. Scipio, unwilling to lose so many men—and their treasured standards—led a rescue party that drove off Hasdrubal’s men. Then and there, the relieved Roman soldiers honored Scipio with a crown, woven from grass plucked from the field of battle. Later, Scipio notched another success by convincing Phameas to join the Romans, bringing with him 2,200 cavalry.

In the first year of the Third Punic War the Romans had made a poor start. There was hope in 148 BCE for better leadership from a new consul, Calpurnius Piso and his legate Lucius Mancinus, who commanded the fleet. They continued the war but with no better success.

Fortune smiled on Rome the following year as Scipio Aemilianus took leave from the army to sail to Rome and run for election as an aedile, a step up for him in the cursus honorarium. The young officer’s achievements were so well known in Rome that he won an even higher prize than he sought: election as a consul. This was unexpected, as legally, Scipio was six years too young to serve as a consul. Further stretching law and precedent, there was an understanding that the consulship might not be limited to the customary one year, but would last until Scipio could win the war.

Scipio returned to Africa to take full command. With him was Gaius Laelius, whose father of the same name had been a friend of the elder Scipio Africanus during the Second Punic War.

Upon his return, Scipio found that Mancinus had tried to attack the city from the sea, and gotten his army into a tight spot. They scaled some lightly defended cliffs and secured a foothold by the edge of the main city walls, but a counterattack left them trapped on the rocky heights overlooking the sea. Piso, meanwhile, had been frittering away his time campaigning against small inland towns and strongholds, rather than pressing the main siege. Scipio relieved Mancinus and continued to press Carthage.

Soon after taking command, Scipio captured the suburbs of Megara. At first, he launched two simultaneous attempts against the wall that stretched across the isthmus, but both attacks failed. The Romans found a weak spot, though, by a privately-built stone tower that stood outside the walls. Soldiers hauled up planks and bridged the gap between the top of the tower and the ramparts, and poured over the wall to seize all of Megara. Hasdrubal the Boetharch was compelled to bring his field army into the city. He deposed the garrison commander, whose name was also Hasdrubal, and ordered his execution after conviction on false charges.

The first action of the new commander Hasdrubal doomed all Roman prisoners within the walls. He ordered them taken to the parapets to be tortured in plain view of the Roman troops, then hurled off the walls to their deaths. Any of his countrymen who raised objections to the unneeded provocation received similar treatment.

Next to draw the attention of Scipio was the entrance to the merchant harbor. Blockade runners still slipped in and out, bringing in food and reinforcements. To close the harbor, Scipio set his men to haul giant stones to build a mole blocking the entrance. Two months of patient work had just about sealed the harbor when the Carthaginians revealed a surprise to the Romans.

Fifty newly built triremes, accompanied by a host of smaller war vessels, shot out of a newly cut gap in the sea-facing side of the round naval harbor. Although Carthage had given up nearly all of its navy, there remained vast stocks of timber, ropes, sailcloth, and other maritime materials in the city. Thousands of workers constructed a powerful new fleet, hidden from the Romans by the harbor walls and a remarkable veil of secrecy.

Powered by sails and oars, the Carthaginian ships surged out to sea. As if reveling in their freedom, they sped far from shore and maneuvered some distance from Scipio’s warships. Had they attacked the Roman ships immediately, the element of surprise could have given them a resounding victory and dealt a disastrous setback to the siege. Instead, the new fleet safely returned to their harbor.

Three days later, the Carthaginian fleet again poured out of the harbor, and this time, made for the Roman ships. The Carthaginians got the better of the battle, but they opted to head back to the harbor before nightfall. Several of their ships were lost by collision when trying to squeeze back into the narrow entrance. Their partial success made no real impact on the Roman siege.

The siege quieted for the winter months. Nepheris, then commanded by an officer named Diogenes, still sheltered Carthaginian troops who attacked Roman detachments and gathered supplies for Hasdrubal’s garrison. Scipio and Laelius led successful assaults on the outlying enemy camps and Nepheris itself. With the fall of Nepheris and the destruction of Diogenes’ army, the remaining North African forts and towns surrendered to Rome, leaving Carthage reduced to the city itself.

Under the special arrangement devised in Rome, Scipio retained the post of consul, and command of the forces in North Africa for the year 146 BCE. He led a formal prayer ceremony to the gods of Carthage, asking them to abandon the city and its people. The gods, he promised, would find new temples and sacrifices among the victorious Romans.

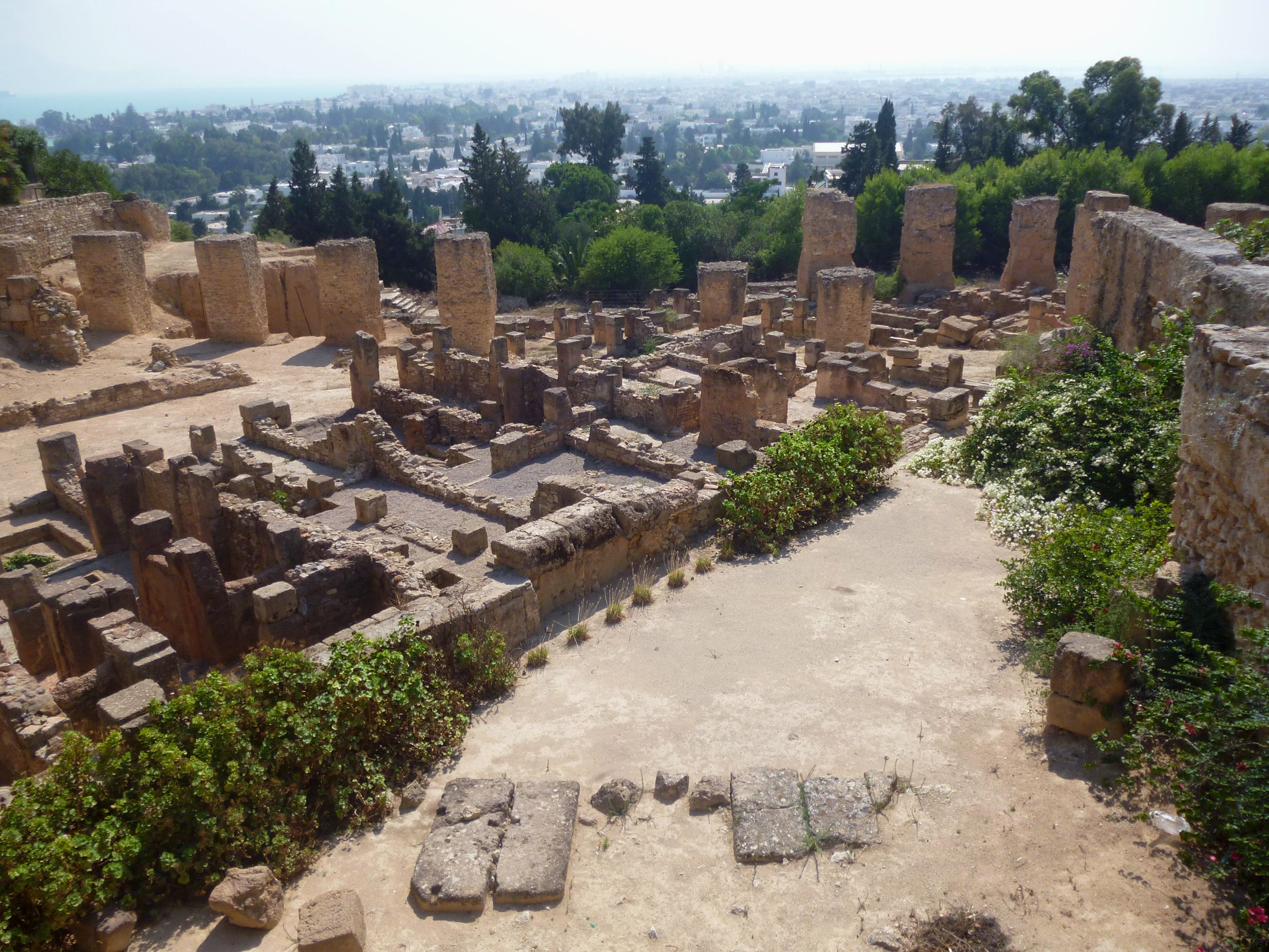

Back at the city, Scipio and Laelius led a new offensive. This time, they burst through the southern defenses and captured both of the inner harbors and the surrounding lower part of the city. The soldiers and townspeople who still resisted pulled back toward the Byrsa, a hill covering much of the core of the old city. Covered with buildings and temples, the Byrsa was protected by steep sides and stone walls.

Three broad streets led from the harbor area to the Byrsa. The distance was measured in city blocks rather than miles, but it took six days of urban warfare for the Romans to reach the slopes of the hill. The streets on the way were lined with massive apartment buildings as high as six stories. From their windows, the Romans were “assailed with missiles.”

The legionnaires adapted themselves to the grim realities of urban warfare. They attacked one building at a time, breaking down the doors and fighting their way up the stairs to each floor. In every story, they fought room to room, smashing down doors and through walls as necessary. Everyone found inside, from enemy soldiers to children and families, was put to the sword. Once a rooftop was captured, legionnaires laid timbers across gaps between buildings and charged onto the next roof. Each building thus became an isolated fortress, with the defenders fighting Roman troops from above and below. Fighting continued on the ground as well. Soldiers battling in the streets faced not only projectiles dropped or shot at them from the high windows, but combatants on the upper stories “were hurled alive from the roofs to the pavement, some of them alighting on the heads of spears or other pointed weapons, or swords,” wrote Arrian.

Once the three streets leading to Byrsa were secured, the Romans set the captured district on fire. Untold numbers of women, children, and old men who found temporary shelter in the lofty tenements were killed by the flames or crushed beneath collapsed timbers and bricks. The cruel and grim fate of the conquered city was likely what Scipio’s soldiers imagined would have been their own fate, should the war have ended differently, with a vengeful Carthaginian army grinding its way into the heart of Rome.

Rising above the top of the Byrsa was the Temple of Eshmoun, the Phoenician and Carthaginian god of healing. Among the last defenders of Carthage were 900 Roman deserters, who preferred certain doom in the besieged citadel than the harsh justice their former army would inflict upon them.

After holding out as long as they could, the Roman renegades and die-hard Carthaginians gathered in the Temple of Eshmoun, looking out over the dying city. It was as if Scipio’s prayer had worked, turning their own gods against them. Facing a hopeless present with no future, the besieged soldiers and refugees assembled inside the temple, and set it afire.

Hasdrubal the Boetharch was not among the last hold-outs on Byrsa. He conducted quiet negotiations on his own behalf with the Romans. They agreed the Carthaginian general would surrender in exchange for his life and favorable treatment, including an estate where he could live in retirement.

According to Roman historians, Hasdrubal’s spouse was ashamed of her husband. No one wrote down her name, at least not in any surviving texts, and she is known to history as “the wife of Hasdrubal.” It was said that she stood on the ramparts of Byrsa, and gave a blessing to Scipio. Although he was the destroyer of her city, the Roman leader himself had conducted himself honorably according to the rules of ancient war. Then, she uttered a curse upon her husband for his abandonment of his country and his family. Earning the admiration of future generations of Romans, the wife of Hasdrubal dressed in her finest raiment and took two sons by the hand. They walked together, and made their way to the roof of the blazing Temple of Eshmoun, which became their funeral pyre. The Hill of Byrsa, the mythic birthplace of Carthage, was also the scene of the last moments of the Carthaginian Empire.

After his victory, Scipio Aemilianus became known as Scipio Africanus the Younger. According to legend, he had the very ground of the conquered city plowed up and sown with salt, so that nothing would ever grow there. This tale is no longer taken literally. Just the same, the burned and ravaged city was left empty and abandoned. Some 50,000 survivors—perhaps one-fifth of the prewar population—were spared to be sold into slavery.

Even its conqueror was appalled at the immensity of Carthage’s fiery and blood-soaked end. “Scipio, beholding this spectacle,” wrote Arrian, “is said to have shed tears and publicly lamented the fortune of the enemy.” Reflecting on the fall of past empires, and perhaps with a premonition of the end of Rome, he recited from the Iliad, “The day shall come in which our sacred Troy/ And Priam, and the people over whom/ Spear-bearing Priam rules, shall perish all.”

Eventually a new city grew on the site of Carthage, but it was a new Roman city that left nothing to be seen of the old. The religion, language, history, literature, poetry, and the very culture of Carthage were practically obliterated, leaving this once dominant civilization much shadowed in mystery.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments