By Steven Weingartner

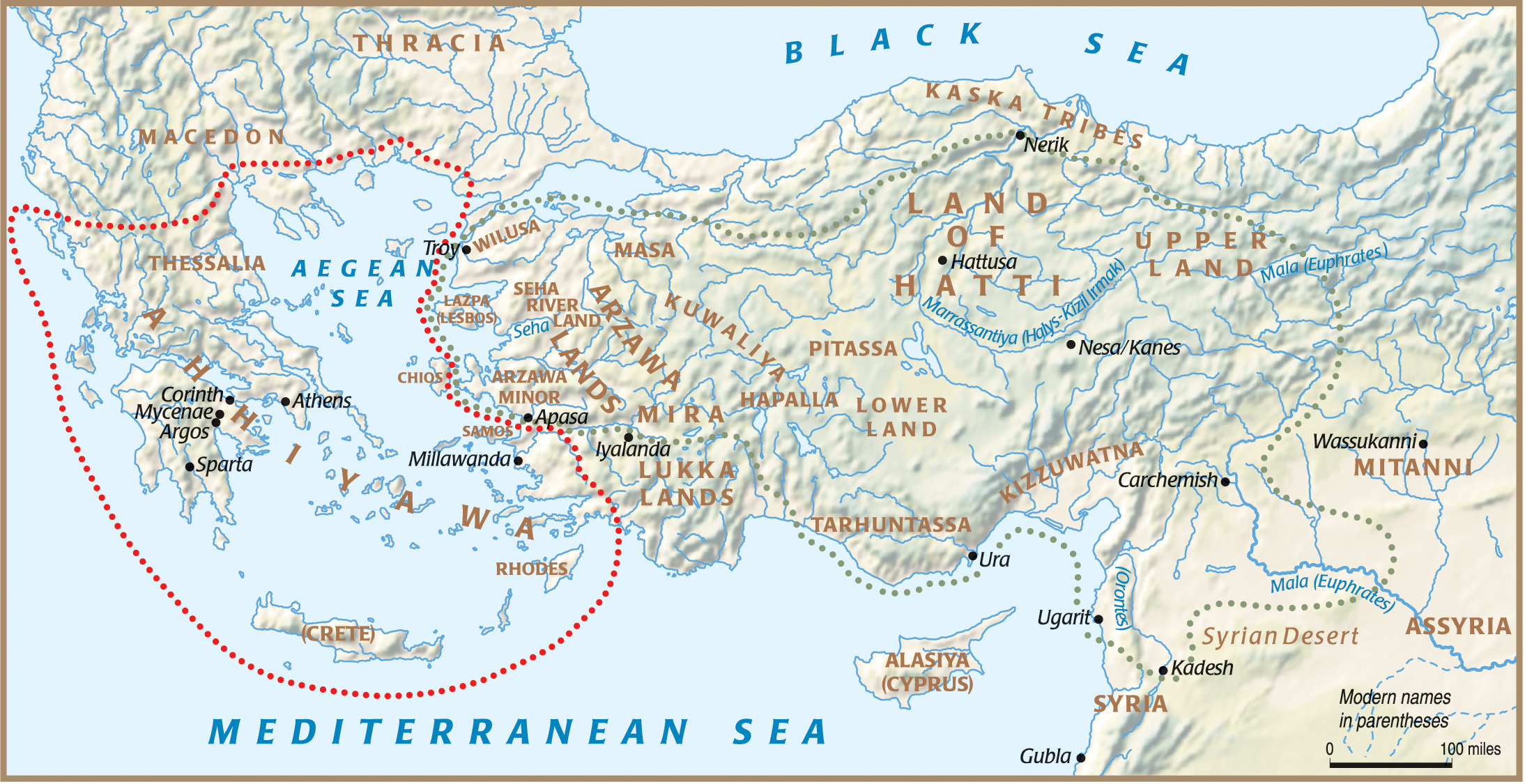

Western Anatolia in the 13th century bc was the main arena for a protracted trial of strength between two vital and aggressive empires, Hatti and Ahhiyawa. Each had carved out a sphere of influence in the region comprising vassal states ruled by local dynasts who were obliged to maintain, assert and, if possible, extend the authority of their respective suzerains. The system was mutually beneficial to the Hittites and Ahhiyawans insofar as it allowed them to remain perpetually locked in contention for mastery of the West even while avoiding direct armed conflict by their respective military establishments. Most if not all of their wars were fought by proxy, that is, by the vassal kings and their dependents, and by freebooters allied with, but not necessarily subject to, either Hatti or Ahhiyawa.

It was a situation rich with opportunity for men of violence and ambition, for kings and men who would be kings. The latter might be mere adventurers, soldiers of fortune who cared nothing for the outcome of the struggle so long as they survived it and were amply rewarded for their services, always in the form of booty, preferably in the form of land and titles. But others were men with a cause and an agenda who would not abandon either in any circumstances, however unfavorable or demanding. Such a man was a warlord of obscure origins, a mercenary captain of unknown lineage and background, but possessing demonstrated military ability and political guile and, not incidentally, a steadfast loyalty to the Ahhiyawan monarchs. He was called Piyamaradu.

He first appears in Hittite historical records—our sole source of information about him—sometime in the early 13th century, possibly in the late 1290s, toward the beginning of the reign of the Hittite Great King and emperor Muwatalli II (c. 1295-1272 bc, see also the Glossary at the end of the article). In all likelihood he was a rebellious Hittite nobleman, perhaps closely related to the royal family, who had come out on the losing end of a dynastic struggle for the Hittite throne, an all too frequent occurrence in Hittite history. The man who won the crown normally tried to reconcile with the losers, eschewing the murder of rivals as both immoral and impolitic. Murder, while it might eliminate one enemy, had a tendency to breed many others, particularly kinsmen and supporters seeking vengeance. But some men just cannot be reconciled. Piyamaradu might have been one of the irreconcilables, unshakeable in his convictions, unyielding in defeat.

But there may be another, simpler explanation for Piyamaradu’s disaffection. Perhaps he was one of those violent souls, familiar to every age, who love strife for its own sake: a natural-born warrior of fiery spirit and fierce passions, craving action, thriving on discord, nursing untold grievances and insults to his honor, constantly seeking battle, adventure, conquests, treasure, power and, perhaps most of all, glory. In any event his reasons for rebellion, whatever they were, proved sufficiently motivating to turn him permanently against his homeland and people. Choosing the path of the renegade, he left Hatti forever to make common cause with her enemies, notably the king of Ahhiyawa.

In order to understand Piyamaradu’s defection and subsequent activities, and why those activities had a significant impact on the Near East and Aegean kingdoms of the Late Bronze Age, it is necessary to set the geopolitical stage and identify some of the actors who strutted their brief hour upon it. In those days Hatti was a great power in the world, a vast empire encompassing much of Anatolia and extending roughly from the Aegean Sea in the west to the Euphrates River and Syria in the east. The Hittite homeland, the “Land of Hatti,” was located in north-central Anatolia and, for political and administrative purposes, it was divided into two regions, the Upper Land and the Lower Land. The empire’s capital (and largest city) was Hattusa, located in the Upper Land.

Because Hatti was a great power her kings were accordingly called Great King, a title reserved for Bronze Age rulers of the topmost rank. In the native Hittite language (called “Nesite” after Nesa/Kanes, an ancient central Anatolian city the Hittites claimed as their place of origin), Great King translated as Salli Hassu (the title hassu, “king,” was applied to vassals). Muwatalli was also hailed as Istanu-mi (synonymously, Sun God or Your Majesty) and Tabarna (“Brave One” or “Ruler,” a title derived from an early Hittite king of that name). An individual brought before the enthroned emperor would prostrate himself and utter “Istanu-mi, Salli Hassu, Tabarna Muwatalli, Hassu Hatti”: “Your majesty, the Great King, the Brave Ruler Muwatalli, the King of Hatti.”

As “Salli Hassu,” Great King, Muwatalli bowed to no man, for no man was his superior. He did have equals, however, Great Kings like himself. In diplomatic correspondence the Great Kings typically addressed each other as “my brother” in recognition of their equality; lesser kings were addressed as “my son.” Muwatalli’s royal brethren were the pharaoh of Egypt and the kings of Babylon, Hanigalbat/Mitanni (until its conquest by Assyria between 1272 and 1267), and Ahhiyawa.

In our time the Ahhiyawan kings are shadowy figures, their names unknown, their individual stories lost to history, consigned to oblivion by a cataclysmic series of invasions, wars, and societal upheavals that effectively ended the Near Eastern Bronze Age and destroyed many of that period’s civilizations, including Hatti, in the first half of the 12th century. But in the time of Piyamaradu, they too were Great Kings of a sprawling empire, holding sway over wide expanses of land and sea and exerting considerable influence on the course of international affairs.

It was a Greek realm: “Ahhiyawa” is the Hittite rendering of “Achaea,” most memorable as the homeland of the Achaean Greeks of the Homeric epics. Comprising a confederation or commonwealth of states whose Indo-European inhabitants spoke dialects collectively referred to as “Linear B” and identified as early variants of Greek, Ahhiyawa (Linear B “Akawiyada,” Land of the “Akhaiwoi”) extended from the Greek mainland across the islands of the Aegean Sea and into parts of Western Anatolia. Its political center of gravity was the citadel of Mycenae, located on a rocky eminence in the Argolid region of Greece’s Peloponnesian Peninsula, leading some scholars to posit “Ahhiyawa” as the Hittite word for “Argeioi,” the Argolid.

The Great King at Mycenae, called “Wanax” in his own Greek language, exercised suzerainty over innumerable lesser kings, princes, potentates, and freebooting captains such as Piyamaradu. The rulers and peoples who acknowledged the Mycenaean king as their overlord were not necessarily ethnic Greeks. This was particularly the case in Western Anatolia where, apart from specifically Mycenaean colonies, the native populations of Mycenae’s vassal states and tributaries were usually Luwians, an Indo-European group that spoke a language closely related to Nesite.

When Muwatalli ascended the Hittite throne Piyamaradu had yet to arrive on the scene and the western regions of the empire were relatively quiescent. Hatti’s sphere included the Luwian-speaking countries of the Arzawa Lands, formerly dominated by the kingdom of Arzawa; dubbed “Arzawa Minor” by scholars, its capital was located on the Aegean coast at Apasa (Classical Ephesos). Other countries in the Arzawa group were Seha River Land and Wilusa, both located on the coast to the north of Arzawa Minor; and Hapalla and Mira-Kuwaliya, located inland to the southeast.

During the third and fourth years (1319-1318 bc) of the reign of Muwatalli’s father, Mursili II, Arzawa Minor led Seha River Land, Hapalla, and Mira-Kuwaliya in a war against the Hittites; Wilusa, an independent kingdom with close ties to Hatti (and which is thought to have been the city of Troy), remained loyal to Mursili. The Hittites won the war and Mursili punished Arzawa Minor by partitioning it among its allies, which were punished in turn by being reduced to vassal status. Wilusa was allowed to retaine its sovereignty in reward for siding with Hatti.

The Luwian kingdom of Millawanda (also known as Milawata), located just south of Arzawa Minor on the Aegean coast, was also allied with Hatti’s enemies in that conflict, even though it was not considered part of the Arzawa group. Technically a loser in the Arzawan War, Millawanda oddly enough got essentially what it wanted, separation from Hatti. Before the war Millawanda had somehow contrived to be associated with both the Hittite and Ahhiyawan empires—officially a vassal of the former but in reality a tributary of the latter. The Mycenaeans had established their presence in Millawanda sometime in the 14th century, probably in the form of merchant colonies. Eventually Millawanda became a de facto Ahhiyawan protectorate. But even as Millawanda was drawn ever more firmly into the Ahhiyawan orbit, serving as Ahhiyawa’s principal foothold and main base of operations in Western Anatolia, it had remained, however nominally, a Hittite vassal.

In the Arzawan War a Hittite regular army invaded Millawanda, seized human captives and livestock, and then withdrew. By the standards of the day, this amounted to a very mild chastisement. Obviously the Hittites did not want to spark an all-out war with Ahhiyawa. But their restraint did not conceal the ease with which they had violated the Ahhiyawan sphere.

The Ahhiyawans were understandably alarmed by this episode. They recognized that the Hittites had become too strong in the region and that, absent a firm response on their part, the day was not far off when the Ahhiyawans would be muscled out of Anatolia, and thereby cut off from their primary sources of copper, tin, and silver. These precious metals were essential commodities of the Bronze Age, the raw materials of empire, as essential to the existence of the polities of the second millennium bc as oil and natural gas are to the advanced nations of the third millennium ad. Tin and copper, melted and mixed, produced bronze; silver was a universally accepted medium of exchange. They were not widely available in mainland Greece or, for that matter, just about anywhere else in the Ahhiyawan realm, excepting its Anatolian territories. And so, in the aftermath of the Arzawan War, the Ahhiyawans returned in force to Millawanda, bent on expanding their power and influence in the West, and thus securing access to precious metals and the mines that produced them.

To that end, Millawanda was made an Ahhiyawan vassal sometime after the Arzawan War. In due course the throne of Millawanda was occupied by one Atpa, a king in little more than name only, in fact a virtual puppet of the Ahhiyawan emperor. Pulling Atpa’s strings was the Wanax’s brother, Tawagalawa, dispatched to Millawanda as the emperor’s personal representative, his viceroy-in-residence. Now it was the Hittites’ turn to be alarmed. The appointment to Millawanda’s viceregal chair of no less a personage than the brother of the Ahhiyawan emperor signaled a heightened sense of purpose in Mycenae with regard to Western Anatolia. It also meant that the Wanax had taken a personal interest in the region’s affairs, a development that augured ill for the Hittites. An emperor’s interest is never casual. And, given the circumstances, the Wanax’s intentions could not be pacifistic. Surely, trouble was brewing in the West.

Enter Piyamaradu.

Piyamaradu must have arrived in the West shortly after the Ahhiyawans reestablished themselves in Millawanda. Evidently he was accompanied by a sizable entourage, including Lahurzi, his brother; Siggaunas, a troop commander; his wife and two daughters, names unknown; and an experienced military cadre of retainers and household troops. Once ensconced in Millawanda, the warlord married his daughters off to Atpa and Awayana, thus binding himself to the kingdom’s ruling house even while ensuring that one of his grandchildren would eventually sit upon the Millawandan throne.

As for the Millawandan brothers, it seems that in Piyamaradu they gained an overlord as well as a father-in-law. In the future Piyamaradu would pretty much do as he pleased in and with Millawanda, using the kingdom as his base of operations against the Hittites and basically calling the tunes to which Atpa and Awayana danced. This must have been the intent of the Ahhiyawans, who surely sanctioned the double marriage as a way of elevating Piyamaradu to a dominant position in Millawanda—an indication of the warlord’s importance in Mycenae’s grand scheme for Western Anatolia.

The Hittites seem to have turned a blind eye to Ahhiyawa’s acquisition of Millawanda as a vassal state, and to the marital shenanigans that facilitated this move. They simply could not afford to dispute the issue and thus add Ahhiyawa to their already sizable list of actively belligerent enemies. In the mountains to the north of Hatti, Kaska tribesmen, longtime foes of the Hittites, were acting up. In Syria an already-problematic situation was worsening as a result of the efforts of the young, dynamic, and extremely militant pharaoh of Egypt, Ramesses II (reigned 1279-1213 bc). Avowedly determined to regain territories lost to Hatti during the reign of Muwatalli’s grandfather, the great Suppiluliuma I, the Egyptian king was marshaling his forces, fomenting discord in Hatti’s Syrian domains, and otherwise making noises that sounded a lot like a war in the making.

The Hittites countered these threats by deploying forces to their northern frontier and to Syria. Troops for the deployments were drawn from formations in the West, resulting in a weakening of the Hittite position in that region. Unable to intervene while the Ahhiyawan absorption of Millawanda played out, the Hittites had to settle for a wink-and-nod relationship with the Greeks that allowed everyone to maintain the fiction that nothing really important was happening there.

Thus war in the West was avoided. But for how long? The Ahhiyawans were surely up to no good, or else they wouldn’t have suffered Piyamaradu to remain at large in Millawanda. War was coming; the only question was when. Muwatalli’s one hope was that Piyamaradu and the Ahhiyawans could be held in check by the combined forces of Wilusa, Seha River Land, and Mira-Kuwaliya. But it was not to be.

Wilusa (i.e., Troy) was the weak link in the Hittite chain of containment. This independent country was a fast friend of Hatti’s and had probably contributed contingents in support of Hittite military operations during the Arzawan War. Sometime thereafter the Wilusan king, Kukkunni, died and was succeeded by Alaksandu, his adopted son. Alaksandu was also a Hittite loyalist. But evidently important Wilusan noblemen as well as a large segment of the Wilusan populace did not share his pro-Hittite sentiments. For that reason his hold on the throne was tenuous.

The Ahhiyawans smelled blood: Alaksandu and his kingdom were vulnerable. But the Greeks would not undertake the conquest of Wilusa with an imperial Ahhiyawan army, for to do so would violate the gentlemen’s agreement that existed between Hattusa and Mycenae to avoid direct confrontations and to foreswear provocative actions by their forces that would likely escalate into an all-out war. Instead they unleashed Piyamaradu.

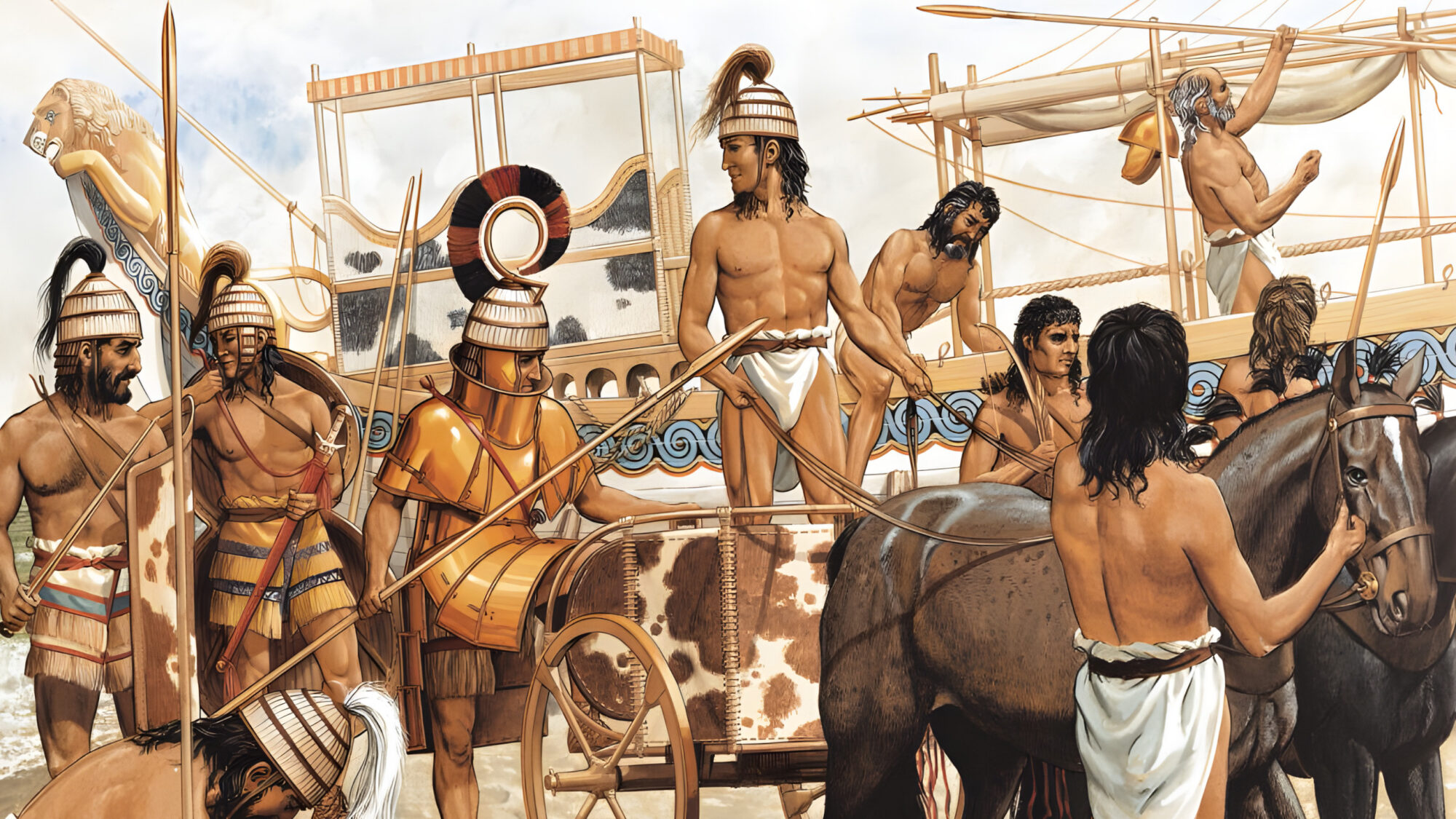

And so Piyamaradu gathered his forces and headed north to conquer Wilusa. What route did he take? An overland journey is doubtful, inasmuch as it would have required the invasion of Seha River Land, whose king, Manapa-Tarhunda, a prominent enemy of Hatti in the Arzawan War, was now Muwatalli’s unswervingly loyal vassal. Likewise, Manapa-Tarhunda’s neighbors, Kupanta-Kurunta of Mira-Kuwaliya and Targasnalli of Hapalla, were the emperor’s steadfast liegemen. The route overland was blocked. Piyamaradu must have journeyed to Wilusa by sea.

His sponsors, the Ahhiyawans, probably outfitted him for the voyage and provided ships for transport. Certainly the movement of a large force by sea—one that included horses and chariots—was well within Ahhiyawan capabilities. Ahhiyawa was, after all, a maritime empire, one of the great thalassocracies of its age (or any age, for that matter), master of the Aegean and a dominant power throughout the eastern half of the “Great Green,” the Egyptian name for the Mediterranean. As the Iliad and the Odyssey clearly illustrate, the Ahhiyawans were magnificently skilled shipwrights and mariners, a seafaring folk with the pothos (a Classical Greek term that translates as “imperative yearning”) to roam the deepwater ways of the world, and who loved nothing more than to raise sail and run before the wind in their sleek, black ships with the bird-headed prows, outward bound on a voyage of exploration, discovery, war, and plunder. Their most revered deity was the mighty Poseidon, god of the sea, earthquakes, and horses, brother of Olympian Zeus and second only to Zeus in power.

Presumably, therefore, Piyamaradu and his army sailed to Wilusa in an armada of Mycenaean warships and transports, perhaps accompanied by Mycenaean military advisers and contingents of elite Greek troops, probably composing his chariotry, the corps d’elite and arm of decision of all respectable Bronze Age armies. But the bulk of his army must have been mercenaries, mostly recruited from the Lukka Lands to the southeast of Millawanda.

The Lukka people were Luwians; they were also formidable warriors. The Hittites claimed the mountainous and mineral-rich Lukka Lands as being within their sphere, but at any given time various Lukka groups were disputing this claim—even while others were serving in the Hittite army. Like the Ahhiyawans, the Lukka were accomplished mariners; and, like the Ahhiyawans, they habitually employed their seafaring skills as corsairs. For that reason the Lukka Lands might have provided Piyamaradu with many of the assets—warships and experienced sailors, as well as soldiers—he needed to invade Wilusa.

It is likely that Piyamaradu’s invasion fleet, numbering several hundred ships, set out for Wilusa in March or April, during the month the Ahhiyawans called Porowito, a name derived from the Linear B word for “sail.” The average warship carried about 60 men: 30 rowers and as many warriors. The transports were larger, capable of carrying loads of up to 150 tons in passengers and freight. Many of these ships would have been converted for the purpose of transporting horses: stalls and bins for fodder would have been built below decks. We can only speculate at the size of Piyamaradu’s army. Logistical considerations probably limited it to between five and ten thousand fighting men, with perhaps an 8:1 ratio of infantry to chariotry. Upon landing in Wilusa, Piyamaradu might have received significant reinforcements in the form of pro-Ahhiyawan contingents.

The subsequent course of events is largely unknown, but it is certain that war ensued and a major battle was fought. The alternative—Alaksandu vacating his throne without a fight—seems unlikely. Alaksandu was, after all, a king, and kings in those days did not gain their thrones or remain long seated thereon unless they were hard and proud and brave. And Alaksandu was an experienced campaigner, a veteran of Mursili’s Arzawan War, the warrior-king of a fair and prosperous realm, a kingdom worth fighting for.

It is easy to imagine a prebattle meeting between Alaksandu and Piyamaradu, the two men driving their chariots onto the open ground between the opposing armies, which waited, splendidly arrayed, while their leaders performed the rhetorical preliminaries that ideally preceded set-piece Bronze Age battles. Wearing magnificently plumed helmets and clad in glittering armor, the antagonists would present, with metrical eloquence and elaborate courtesy, their heroic bona fides. Deeds would be recounted, with an emphasis on feats of arms. Lineages would be recited, always traceable to a divine origin, the mating of human ancestor with god or demigod. Purposes would be announced, motives explained, the legitimacy of one’s cause stipulated, and the spuriousness of the other’s denounced. These would spark anger, vituperation, invective and, finally, warnings: Get thee hence. Run away. Go now or you will die.

Thus addressed, Alaksandu might have responded as Hektor to Aias, on the plain of Troy:

“Do not be testing me as if I were some ineffectual boy, or a woman, who knows nothing of the works of warfare. I know well myself how to fight and kill men in battle; I know how to storm my way into the struggle of flying horses; I know how to tread my measures on the grim floor of the war god” (The Iliad of Homer, trans. Richmond Lattimore).

This barbed and bitter turn in the conversation was de rigueur, a customary and required part of the colloquy that signaled its conclusion. The formalities had been observed, the rituals enacted, the blood gotten up. The adversaries would drive back into the ranks of their respective armies and shortly thereafter the battle would commence, usually with duels between preselected champions followed by the clash of heavy infantry.

Alaksandu lost this war. But he evaded capture, escaping Wilusa to find refuge with the Hittites. In Wilusa, meanwhile, Piyamaradu became king in fact if not yet in name. He also wielded authority over Atpa and probably portions of the Lukka Lands as well. The Hittite renegade had become a major power in the West, the ruler of a mini-empire. His patrons, the Ahhiyawans, must have been pleased. Whatever Piyamaradu achieved redounded to their power and glory; his conquests were their triumphs as well. Because of Piyamaradu the Ahhiyawans had won a big round from the Hittites, gaining the strategic advantage in Western Anatolia.

Piyamaradu’s probable next move would have been obvious to everyone. Between Wilusa and Millawanda was Seha River Land. The conquest of that pro-Hittite kingdom would put Ahhiyawa in control of the entire west coast of Anatolia. In that event the coastal Lukka Lands east of Millawanda would almost certainly declare even more firmly for Ahhiyawa. Thus the Ahhiyawans would dominate the Anatolian littoral from the Black Sea shoulder down the Aegean shore and across the Mediterranean seaboard to the borders of the Hittite subkingdom of Tarhuntassa. Already denied access to the Black Sea by a mountain range swarming with perpetually hostile Kaska tribesmen, the Hittites would find themselves with no outlets to the Aegean and fewer ports on the Mediterranean. The specter of a landlocked empire, a fatal prospect, loomed. Overseas trade would be limited to the ports of Tarhuntassa and its eastern neighbor Kizzuwadna (also a Hittite domain), and to northern Syria; and the latter, although still dominated by Hatti, was threatened by the Egyptians.

The situation demanded immediate military action. But by whom? Hittite regular army forces were unavailable; Muwatalli’s troops were already stretched too thin on several fronts. And so the job of thwarting Piyamaradu was given to a vassal, Manapa-Tarhunda. Placing himself at the head of his army, the king of Seha River Land marched north into Wilusa. There, around the year 1278, he suffered a crushing defeat: “Piyamaradu humiliated me,” he admitted in a letter to Muwatalli (the so-called Manapa-Tarhunda Letter).

While Manapa-Tarhunda’s army retreated across the border into Seha River Land, Piyamaradu might have scanned the strategic landscape for ways to exploit the situation. Several courses were now open to him. A counterinvasion of Seha River Land was one option. With the Seha army reeling in defeat, perhaps the time was ripe to deliver the coup de grâce to Manapa-Tarhunda and his kingdom. The elimination of this last Hittite vassal on the Aegean coast might break Hatti’s power in the West, perhaps irreparably. A pro-Ahhiyawan confederation, something on the order of the old Arzawan combine, could be formed, comprising Wilusa, Seha River Land, Millawanda, and parts of the Lukka Lands.

With Ahhiyawan support Piyamaradu would be installed as the confederation’s primus inter pares, its king of kings: He would finally have his crown. His realm would be large and strong. Perhaps, in time, and with continued support from Ahhiyawa, plus further defections to his camp by disgruntled Hittite vassals, it would grow strong enough to challenge Hatti for mastery of all Anatolia. Were Piyamaradu to prevail over Hatti, the Hittite empire would pass into his hands, and he would become a Salli Hassu, a great king.

But Piyamaradu did not invade Seha River Land. Perhaps he was put off this course by the prospect of fighting a war with extended supply lines in enemy territory. Manapa-Tarhunda had been beaten but not destroyed. His army was intact. And the Seha troops would be defending their homes: They would be angry, desperate, dangerous. An intimate knowledge of the terrain and internal supply lines would further enhance their military effectiveness. All the while Piyamaradu’s left flank would be vulnerable to attack from pro-Hittite vassals to the east.

Kupanta-Kurunta, king of Mira-Kuwaliya from the twelfth year of Mursili’s reign, posed the greatest threat from this direction. His domains, which included neighboring Masa (he was liegelord over that kingdom), shared a long border with Seha River Land, Millawanda, and the Lukka Lands. An able soldier, he was also Muwatalli’s cousin, a son of Mursili’s sister, and rock-solid in his loyalty to the emperor. If Piyamaradu drove into Seha River Land, Kupanta-Kurunta would surely come to Manapa-Tarhunda’s aid.

Instead of invading Seha River Land, Piyamaradu attacked the island of Lazpa (Lesbos). A fief of Manapa-Tarhunda, Lazpa is situated just off the coast of Seha River Land, at the entrance to the Gulf of Edremit, and northwest of the mouth of the River Seha (Classical Kaikos). Manapa-Tarhunda may have anticipated a move on the island but was probably unable to do anything about it; a blockade of his ports by Ahhiyawan warships and Piyamaradu’s Lukka corsairs would have seen to that. As well, he probably had to contend with Millawandan diversionary attacks on his southern border: in the Manapa-Tarhunda Letter the Seha king complained, in the context of Piyamaradu’s Lazpa operation, that the warlord had “set Atpa against me.”

Where did Piyamaradu land? The north shore, opposite the Wilusa coast, would seem an obvious choice. But it would have been just like Piyamaradu to strike directly at Lazpa’s populous heart, the splendid walled city of Thermi on the southeast coast, thereby neutralizing the island’s administrative center and thus paralyzing efforts to mount an organized defense. His knowledge of Thermi and other settlements would have been extensive because of information supplied by previous raiding parties.

Lazpa was a popular target with freebooting Ahhiyawans and their allies. It had much to offer in the way of plunder. The island’s economy thrived, its communities prospered. Productive farms and dense forests provided wheat and timber for export, which brought luxury goods and other commodities in return, resulting in substantial accumulations of material wealth. The latter constituted an irresistible attraction for predatory adventurers, who were drawn to the place like bees to pollen. And, like bees to pollen, marauders came to satisfy more basic appetites. Lazpa’s women were famous and much prized for their beauty. Ahhiyawan pirates routinely seized and carried them off to their warships, their homes … and their bedchambers.

The legendary Achilleus, “the best of the Achaeans” and a prolific womanizer, seems to have been especially fond of Lazpan women. He was said to have raided Lesbos on several occasions, once capturing the fortified city of Mithymna (on the north coast) with the aid of a Lazpan princess, whom he had seduced. On another raid he abducted numerous maidens, craftswomen of some sort, “who in their beauty surpassed the races of women.” (Achilleus must have been two or three generations younger than Piyamaradu and would have carried out his raids sometime before the fall of Troy, thought to have occurred about 1183, less than a century after Piyamaradu; see sidebar.)

An oblique but telling reference to Lazpa’s collective affluence is provided in the final book of the Iliad when Achilleus, meeting with Troy’s grieving King Priam—whose eldest son, Hektor, Achilleus had recently slain—rather poignantly observes that Priam’s fabled wealth once surpassed even the immense riches of that island. Given the frequent and frequently successful efforts of Achilleus and other Ahhiyawan brigands and buccaneers, Piyamaradu not least among them, to deplete those riches, it comes as no surprise to learn that Lazpa fought on Troy’s side in the Trojan War. One can hardly blame the Lazpans for their antipathy toward the Mycenaean Greeks.

Piyamaradu did not stay long on Lazpa, leaving soon after attacking it, perhaps within days. A lengthy stay was not desirable, inasmuch as it would tie down forces that could be put to better use on the mainland against the Hittites and their allies. Anyway, Piyamaradu had achieved his purpose, that being to further weaken an already battered and bloodied foe.

Piyamaradu departed in advance of his troops, putting his henchman Siggaunas in charge of the mopping-up operations, which mainly entailed the evacuation of Ahhiyawan sympathizers. Of the latter there was no shortage. Employed on Lazpa when Piyamaradu attacked it were large numbers of workers, craftsmen, and skilled laborers brought there from Seha River Land and Hatti. (Among them were basket weavers, which calls to mind the Lazpans abducted by Achilleus some 90 years later, beautiful young women “skilled in crafts” according to one translation of the Iliad, “the work of whose hands is blameless” according to another.) The Lazpan workers fell into two categories: those in the service of Manapa-Tarhunda and those in the service of Muwatalli. The emperor’s workers were further divided into two subgroups, those who “belonged to the gods” (that is, temple workers) and those who “belonged to His Majesty.”

The Manapa-Tarhunda Letter does not specify whether the craftsmen and women were hired laborers, indentured servants, or slaves. The Seha king, however, is clear about their behavior, which was worse than bad; which was, in fact, altogether treasonable. When Piyamaradu attacked Lazpa, wrote Manapa-Tarhunda, “all of them [the workers] without exception joined in; and whichever workers belonged to His Majesty, all of them without exception joined in.” Even a Hittite overseer, “the domestic and table man assigned to the workers, he made those, too, join in.”

Reading between the lines, one finds indications of a conspiracy between Piyamaradu on the one hand and the workers and the Hittite overseer on the other. Something was very rotten in the state of Seha River Land. The stench of treason surely reached the nose of Muwatalli, now enthroned in Tarhuntassa City, the new capital of the Hittite empire. (Muwatalli had moved the seat of government from Hattusa in order to distance it from the Kaska tribes in the north while permitting him to keep a closer watch on Syria, where tensions with Egypt were mounting.) But the emperor was preoccupied with the troubles in Syria and therefore unready to depose Seha River Land’s manifestly and grossly incompetent king. Manapa-Tarhunda’s failings could be overlooked, at least for a little while.

The rebellious workers fled Lazpa aboard Siggaunas’s ships. The fleet sailed to Millawanda, where Siggaunas presented the workers to Atpa, who at first happily accepted them. Soon after their arrival, however, Muwatalli’s workers pulled a sudden about-face, deciding that they wanted to be Hittite subjects after all. Thus, in a petition addressed to Atpa, they announced that “we are tributaries of Muwatalli and we came over the sea to Lazpa to do his bidding. Let us render our tribute to the Great King! Siggaunas committed a crime by taking us from Lazpa.”

Blaming Siggaunas for their predicament was a masterpiece of craven prevarication, one designed to sway Atpa even as it placated Muwatalli. Atpa, somewhat of a craven himself, was inclined to release them. He must have felt that there was nothing good to be gained from holding Hittite subjects against their wishes. The workers would make trouble for him and the Hittites, seizing upon their predicament as a casus belli, might invade his kingdom.

“He would have let them go home,” reports Manapa-Tarhunda, but Atpa did not reckon with Piyamaradu. Atpa’s father-in-law had not returned to Wilusa after the Lazpa raid; he was in Millawanda, outside the city, probably relaxing on a country estate, where he could visit at leisure with his daughters and any grandchildren they might have produced, plot his next move, and take inventory of his recently gotten plunder. Then he got wind of what Atpa was up to, and he put his foot down.

“Piyamaradu dispatched Siggaunas to Atpa and spoke to him in this manner: ‘A type of Storm God presented to you a boon, why shall you now return them?’”

One can almost see Atpa squirming while Siggaunas delivered Piyamaradu’s message. The workers were a gift from heaven and therefore not to be rejected: One does not refuse what the gods give freely. That was what Piyamaradu had said, speaking through Siggaunas. What he really meant, and what Atpa had to understand, was that one does not refuse Piyamaradu. This command was no less firm, nor any less ominous in tone, for its being framed as a question. The polite phrasing was a mere courtesy. The question carried an order that was to be obeyed, not answered. Now it was the king of Millawanda who performed an about-face. “When Atpa in his turn heard the word of Piyamaradu, he did not return the workers.”

Informed of these developments, Muwatalli mobilized his army. It was bad enough that Piyamaradu had carried off his workers, far worse that he refused—through Atpa—to let them go. Similar circumstances had precipitated the Trojan War. Alexandros abducted Helen from Sparta and would not send her back, thus dishonoring the house of Atreides and all who served it. The deed was unpardonable, the only redress was war. So it was for Muwatalli. Piyamaradu’s defiance constituted both a personal insult and a direct challenge to the Great King’s authority. Muwatalli could not fail to respond: His vassals were watching, looking for signs of weakness, an opportunity to revolt, to defect to the Ahhiyawan camp. Military action was required. An example had to be made.The warlord had to be punished.

Ever the risk-taker, Piyamaradu might have been gambling that Hatti’s looming war with Egypt would keep Muwatalli’s attention focused on Syria. But he had overplayed his hand. Egyptian chariotry did not ride to Piyamaradu’s figurative rescue: The pharaoh was not ready to challenge the Hittites. Muwatalli was free to go after Piyamaradu. By challenging Muwatalli’s authority, Piyamaradu had provoked the Great King into asserting it.

There is in all this the sense that Piyamaradu had, in Muwatalli’s view, transgressed in a manner that permitted no redemption. Like Colonel Kurtz, the renegade Special Forces operations officer in the film Apocalypse Now, he had crossed certain lines, moral as well as geographical, into a realm from which he could not return. “He’s out there operating without any decent restraint, totally beyond the pale of any acceptable human conduct, and he is still in the field commanding troops.” Thus spoke the film’s American general to the Special Forces captain assigned to track down and assassinate Kurtz. Muwatalli might have used similar language in his marching orders to Gassu, the general who would head the punitive expedition to the West. Piyamaradu was to be terminated “with extreme prejudice.”

Gassu and his army marched into the West, probably accompanied by Alaksandu, Wilusa’s deposed king. En route Gassu collected vassal contingents, among them the forces of Mira-Kuwaliya, led by that country’s king, Kupanta-Kurunta. The combined army crossed the Mira frontier into Seha River Land: “Gassu arrived,” Manapa-Tarhunda reported, “and brought along the Hittite troops.” The army halted to give diplomacy one final chance. “Kupanta-Kurunta sent a message to Atpa: ‘The workers of his majesty who are there with you, let them go home!’” Atpa, who was equal in kingly rank and stature to Kupanta-Kurunta, obeyed the order as if it had issued directly from the emperor himself: “And he let the workers who belonged to the gods, and whichever belonged to His Majesty, all of them without exception to go home.”

This time Piyamaradu was not there to stop him. The warlord had probably returned to Wilusa to defend the kingdom should Gassu and his army turn north. It seems that Atpa, absent Piyamaradu’s steadying presence and fearing that Gassu’s army would head south to attack Millawanda and free the workers, had lost his nerve.

Or not. It is possible that the release of the workers was part of a strategic gambit to lure the Hittite army away from Millawanda and north to Wilusa. If, as seems to be the case, the Hittite army was superior to the forces available to Piyamaradu, the warlord and his Ahhiyawan sponsors might have already conceded the round to Muwatalli, before any battles were fought, while the emperor’s troops were still in Seha River Land. A Hittite regular army, augmented by vassal troops, led by a competent general, and motivated by Muwatalli’s determination to set things right in the West, would prove unstoppable.

Nor could Piyamaradu expect much help from Mycenae. The Ahhiyawans, as always, were disinclined to intervene directly in the affairs of the West. After all, Ahhiyawa and Hatti were formally at peace, a fiction to be sure, but a useful fiction nonetheless, one that both the Wanax and the emperor wanted to maintain.

In the circumstance, defeat, somewhere, was inevitable: Territory, somewhere, would be lost to the Hittites. But which territory? Certainly not Millawanda. Atpa’s kingdom was Ahhiyawa’s strategic lynchpin in Anatolia, the base of Ahhiyawan operations, the center of Ahhiyawan power. The loss of Millawanda was impermissible. Wilusa, on the other hand, was not vital to Ahhiyawan interests. Wilusa was expendable. Wilusa was to be sacrificed on the altar of Ahhiyawan realpolitik.

Thus, before his departure to Wilusa, Piyamaradu might have instructed Atpa to obey any further demands to release Muwatalli’s workers. In doing so Atpa would satisfy Muwatalli’s honor and, presumably, forestall an invasion of Millawanda by removing the pretext for invasion. The Hittites, ever mindful of Ahhiyawan sensitivities with regard to Millawanda, would have been relieved to abandon any plans to attack that country. Their southern flank thus secured, the Hittites could then safely move against Wilusa to eliminate Piyamaradu. Which was, after all, Muwatalli’s main objective.

In due course, writes Manapa-Tarhunda, Gassu and his army “set out again to the country of Wilusa in order to attack it.” But the king of Seha River Land did not accompany them: “I, however, became ill. I am seriously ill, illness holds me prostrated!”

Conveniently stricken before yet another confrontation with his nemesis, Manapa-Tarhunda remained in Seha River Land while the Hittites and their allies reconquered Wilusa and reinstalled Alaksandu on the kingdom’s throne. But they failed to capture Piyamaradu. Once again the warlord slipped their grasp, possibly fleeing across the sea to one of Ahhiyawa’s islands, eventually returning to Millawanda. Shortly thereafter Manapa-Tarhunda’s forces reoccupied Lazpa. Presumably the king had recovered from his “illness,” although one suspects that his cure owed more to Piyamaradu’s defeat and departure from his kingdom than to any marked improvement in his health—which may never have been quite so bad as he wanted Muwatalli to believe.

Muwatalli was no fool. He knew what Manapa-Tarhunda was about. In different circumstances he might have tolerated the vassal’s shortcomings, permitting him, for the sake of maintaining regional stability, to stay on as king of Seha River Land. But unfortunately for Manapa-Tarhunda, and notwithstanding Piyamaradu’s ouster from Wilusa, the circumstances militated against a business-as-usual approach in that kingdom. The Ahhiyawans remained powerful in the West, dominating the Aegean and its trade, controlling most of Anatolia’s offshore islands, effectively ruling Millawanda, constantly stirring up the Lukka Lands, and, not least, providing continued support to Piyamaradu, who was still very much at large. The challenges to Hittite authority, both actual and potential, were serious and clearly beyond Manapa-Tarhunda’s ability to cope with. It was time for the king to go.

And so the emperor deposed Manapa-Tarhunda. The old man was sent into exile, in all likelihood a comfortable one, probably in Tarhuntassa, where Muwatalli’s agents could keep an eye on him. His son Masturi replaced him on the Seha throne.

About the same time, Muwatalli concluded a treaty with Alaksandu that ended Wilusa’s status as an independent kingdom. It was henceforth a Hittite tributary state, with Alaksandu formerly enfeoffed to the emperor. One of the provisions of the so-called Alaksandu Treaty put the king of Wilusa on notice that he was liable for service in the emperor’s wars. He probably fulfilled this obligation in Hatti’s war with Egypt, which broke out in 1275 and culminated in the Battle of Kadesh. An Egyptian register of the Hittite order of battle lists the Dr’dny, or Dardany, who could be the Dardanians, Homer’s alternate name for the people of Troy/Wilusa.

The Battle of Kadesh was at once a tactical standoff for both sides and a strategic victory for the Hittites, who were able to increase their holdings and influence in Syria at Egypt’s expense. Muwatalli died a few years later, probably in 1272. He was succeeded by Urhi-Tesub, his son by a concubine. Because he was pahurzzi, a bastard, Urhi-Tesub was seen by many as unfit to be king; his uncle, Hattusili, was the widely preferred choice. The younger brother of Muwatalli and the youngest of Mursili’s four (legitimate) children, Hattusili had ruled Hatti’s northern territories, including the former capital, Hattusa, almost from the start of Muwatalli’s reign. In 1267 Urhi-Tesub transferred the seat of imperial government back to Hattusa (from Tarhuntassa), a move aimed at eliminating Hattusili as a rival. Instead it was Urhi-Tesub who was eliminated. Defeated and deposed in 1266, he fled Hatti, never to return, living out his final years in Egypt as Ramesses II’s adviser on Hittite affairs. We need not feel sorry for him. His position in Egypt was a comfortable sinecure. It is his uncle, who ascended the throne as Hattusili III, who deserves our sympathy. He had to contend with Piyamaradu.

Because of gaps in the historical record, we know almost nothing of Piyamaradu’s activities during the 10-year period beginning approximately with Muwatalli’s Syrian campaign and ending with the Hittite civil war and Hattusili’s accession. He probably stayed out of the conflict, since he had no real stake in the outcome except to see the Hittite empire emerging from it significantly weakened by the fighting. Watching from the sidelines of Milla-wanda, Piyamaradu must have been con- siderably entertained by the spectacle of his enemies rending their own realm asunder, a task to which he had long applied himself with so much devotion, energy, and ingenuity.

Hattusili was in his fifties when he ascended the throne. Although he reigned for 30 years (c. 1267-1237 bc) his health was always poor, the result and continuation of chronic childhood illnesses. Piyamaradu was probably about the same age as Hattusili, if not slightly older. Unlike the emperor, however, he seems to have been in fine fettle. Nor was his enmity for Hatti at all diminished. Very probably his hatred had grown and intensified as a consequence of his defeat in Wilusa. It was just as well, for in the aftermath of Hattusili’s coronation, Ahhiyawan involvement in the affairs of Western Anatolia increased markedly, with the Greeks actively fomenting rebellion throughout the region. As always, Piyamaradu served as Mycenae’s primary agent provocateur; and, as might be expected, the Lukka people proved most responsive to his blandishments.

In due course the Lukka Lands were boiling with revolt. A desperate Hattusili, who also faced renewed hostilities with the Kaska, concluded a peace treaty with Ramesses in the autumn of 1259, during his eighth regnal year. Having finally and permanently normalized relations with his country’s longstanding foe—never again would Hatti and Egypt go to war with each other—the emperor was able to devote more attention to the threats on his northern frontier and in the West.

Piyamaradu struck first. Our source for what transpired is the so-called Tawagalawa Letter, written after the ensuing events by Hattusili to Tawagalawa’s brother, the Great King of Ahhiyawa. According to Hattusili, an embassy of Lukka rebels journeyed to Millawanda, where they “brought their plight to the attention of Tawagalawa.” The Ahhiyawan viceroy, presumably after consulting with his brother in Mycenae, rendered assistance to these “men of Lukka” in the form of an army commanded by Piyamaradu. In order to maintain the pretense of Ahhiyawan noninvolvement, Piyamaradu’s army marched under the warlord’s banner as an autonomous force; it consisted of mercenary contingents, probably composed of Lukka rebels, Millawandan and Mycenaean “volunteers,” and even a few dispossessed Mariyanna (warrior-caste chariot fighters from the now-defunct Mitannian empire).

Crossing the Millawandan frontier into the Lukka Lands, Piyamaradu captured and burned the pro-Hittite city of Attarimma. He then occupied the city of Iyalanda, which was in rebellion against Hatti. In the meantime Hattusili, responding to an appeal by Hittite loyalists (possibly Attarimman refugees), launched a counterinvasion of the Lukka Lands with the stated objective of bringing Piyamaradu to heel. The warlord, with typical bravado, demanded to be made a vassal king of his newly conquered territories. Amazingly, the emperor acceded to the warlord’s demand, perhaps reasoning that Hatti would be better off for having Piyamaradu as a vassal than an enemy.

Hattusili’s son, the crown prince Nerikkaili, was dispatched to Iyalanda for the purpose of escorting Piyamaradu to the Lukka city of Sallapa, which Hattusili had occupied and where the ceremony of investiture was to take place. In Iyalanda, however, Nerikkaili was rudely received by Piyamaradu, who silenced the crown prince and belittled him in the presence of numerous foreign dignitaries. Hatti’s heir apparent, sneered Piyamaradu, was unworthy to serve as his escort to Sallapa; and, anyway, Piyamaradu would not go to Sallapa because the Hittites were plotting to murder him. That being the case, the emperor should “give me a kingship here on the spot,” that is, declare from afar that Piyamaradu was to become a hassu in the Lukka Lands.

Realizing that Piyamaradu was toying with him and angered by the public humiliation of his son, Hattusili pushed on to the city of Waliwanda. There he wrote Piyamaradu to inform him that a kingship might still be his, but only if he vacated Iyalanda. Piyamaradu was not intimidated. Hattusili recorded that, “When I reached Iyalanda, Piyamaradu offered battle to me in three places. That terrain was rugged.” Hattusili dismounted his chariot fighters and personally led them in counterattacks against Piyamaradu’s forces, which were positioned on the heights overlooking the Hittites’ line of march. “So I made the ascent on foot and defeated the enemy there.”

Piyamaradu’s beaten forces pulled back beyond the city, accompanied by 7,000 Iyalandans. Hattusili contended that the refugees were Hittite subjects and called upon Piyamaradu to release them at once. The warlord ignored the emperor. Obviously frustrated, Hattusili ordered his troops to ravage Iyalanda and to seize its remaining inhabitants for resettlement in Hatti.

That done, Hattusili resumed his offensive, only to be ambushed again, this time by forces under the command of Piyamaradu’s brother, Lahurzi. The Hittites won this engagement as well, but the rebels held them long enough to allow Piyamaradu and his host to withdraw across the frontier into Millawanda. The Hittites pursued, stopping just short of the border in the city of Abawiya, where the emperor composed another letter to Piyamaradu: “Come here to me,” he commanded. Hattusili also wrote a letter to the Wanax: “I have sought to seize Piyamaradu on this account, because he is continually attacking this land of mine. Does my brother know it or not?”

The Wanax’s reply was delivered by an envoy who, Hattusili pointedly observed, “did not bring me any official greeting, nor did he bring to me any gift.” Instead the envoy simply informed Hattusili that the Wanax had instructed Atpa to hand over Piyamaradu to the Hittite emperor, on condition that Hattusili would not harm the warlord nor take him out of Millawanda.

The Wanax’s deliberate failure to provide either greetings or gifts—standard openings in the epistolary-ambassadorial discourse between great kings—was a serious breach of etiquette, one that signaled the Wanax’s displeasure with the Hittites and the actions they had taken and were about to take. It signaled as well that this communication from the Wanax was purely informal, that he was speaking arbitrio suo, as it were, on his own authority as an equal and a “brother” of the emperor and not in his capacity as the Ahhiyawan head of state. That said, the Wanax implicitly sanctioned what would amount to a Hittite invasion of Milla-wanda and a friendly meeting between Piyamaradu and Hattusili.

Hattusili could not have been wholly pleased with this message. He might have thought that he could do as he pleased with both Millawanda and Piyamaradu. But in doing so he would risk a general war with a maritime power that dominated the sea lanes linking the Hittite empire with its Mediterranean trading partners. The Ahhiyawans could not challenge the Hittites on land, but they could destroy Hatti’s overseas trade, the lifeblood of the empire, without which the Hittite economy would collapse. And so Hattusili composed a circumspect reply to the Wanax: “My brother has written to me as a Great King, my equal,” the emperor said, “and do I not heed the word of an equal?”

Hattusili and his army marched across the frontier into the kingdom of Millawanda. The Hittites encountered no resistance. Obviously the Millawandan army, as well as any Ahhiyawan units stationed in that country, had been ordered to give the Hittites a wide berth. “So I proceeded to the city of Millawanda,” recounted Hattusili, “because I thought: ‘Let my brother’s subjects hear what I have to say to Piyamaradu.’”

Piyamaradu wasn’t interested in Hattusili’s proposals. While the Hittites advanced on Millawanda City, the warlord, his entire household, his wife and children, his troops, and the 7,000 Iyalandan refugees all departed from Millawanda by sea: “Piyamaradu came away from the city by ship,” Hattusili reported, in all likelihood sailing to nearby Samos, one of the larger and more prosperous islands in the Ahhiyawan imperium. In a move surely aimed at delegitimizing the subsequent proceedings, or at the very least rendering them irrelevant, Tawagalawa also left Millawanda, perhaps joining Piyamaradu on Samos, there to wait out the course of events.

Although Hattusili must have known that he could accomplish nothing of lasting importance in the viceroy’s absence, he went ahead and met with Atpa and Awayana, who “both listened to the charges which I had directed against Piyamaradu.” In the Tawagalawa Letter, Hattusili claimed that the brothers had been less than forthcoming in their communications with the Wanax, concealing the awful truth about Piyamaradu out of loyalty to their father-in-law. Therefore, said Hattusili, “I put them under oath to report the matter accurately to you,” as though their opinions counted for anything in Mycenae.

The meeting ended with Hattusili tersely ordering Atpa: “Get up! My brother [the king of Ahhiyawa] has sent you a directive, that you should bring Piyamaradu forth to the Hittite king. So bring him here.” Atpa was to promise Piyamaradu that he would not be in any way mistreated. A high-ranking Hittite official would be sent to the Ahhiyawans as a guarantor of the warlord’s safety. Nevertheless, Piyamaradu refused Hattusili’s summons. “I can’t get rid of my fears,” he supposedly replied.

Despite this latest rejection by Piyamaradu, Hattusili was still willing to give diplomacy a chance. A final hostage deal was proffered, with Tapala-Tarhunta, the royal groom, chosen to serve as Hattusili’s collateral. Hattusili assured the Wanax that Tapala-Tarhunta was “not some man of low rank,” but rather a kinsman through marriage to a relative of the Empress Puduhepa. Moreover, Tapala-Tarhunta was friends with both Hattusili and Tawagalawa: “In my youth he stood beside me on the chariot,” the emperor noted, and he had stood “on the chariot alongside your brother Tawagalawa.”

Through intermediaries, Hattusili urged Piyamaradu to “come, make your case before me, and I will put you on the road to promotion.” In the event that Piyamaradu was dissatisfied with the emperor’s proposals, then “my man will escort you back into the land of Ahhiyawa in the same manner as he came here with you.” Tapala-Tarhunta would remain with his Ahhiyawan keepers until Piyamaradu had returned to Ahhiyawa.

It was all to no avail: Piyamaradu spurned the emperor yet again. Finally realizing the futility of his efforts, Hattusili quit the city and country of Millawanda, returning with his army to the Lukka Lands and eventually to Hattusa. In the closing lines of the Tawagalawa Letter, Hattusili told the Wanax that, inasmuch as the leaders of Piyamaradu’s Iyalandan refugees refused to return to their homeland and were actively abetting Piyamaradu, “You, my brother, must put the leaders on trial.” Hattusili avowed that he was willing to forgo extradition of any rebel leader who, in the course of the trial, stated that he wanted to permanently defect to Ahhiyawa: “If any lord says: ‘I crossed over for the sake of a fugitive,’ let him stay there. But if he says: ‘Piyamaradu forced me to join him,’ then let him come back to me.”

As for Piyamaradu, it had come to Hattusili’s attention that the warlord, operating from his island base in the Aegean, was planning new attacks against the emperor’s territories. “It is reported that Piyamaradu has been saying: ‘I will go over into the land of Masa or the land of Karkiya, but the captives, my wife, children and household I will leave here,’ that is, on the Ahhiyawan island that was now his home and stronghold. Hattusili complained that the Wanax was actively assisting Piyamaradu: “Now according to this rumor, during the time when Piyamaradu leaves behind his wife, children and household in my brother’s land, your land is affording him protection. But he is continually raiding my land; but whenever I have prevented him in that, he comes back into your territory. Are you now, my Brother, favorably disposed to this conduct?”

It was a rhetorical question: Of course the Wanax was disposed to this conduct; as before, as always, he was backing Piyamaradu to the hilt, providing the men, materiel, and resources the warlord needed to prosecute his unending war with the Hittites. But Hattusili persisted, for appearances’ sake, to pretend that the Mycenaeans were open to alternatives. “If you are not favorably disposed to Piyamaradu’s conduct, then, my Brother, write him at least this: ‘Rise up, go forth into the land of Hatti, your lord has settled his account with you! Otherwise come into the land of Ahhiyawa, and in whatever place I settle you, you must remain there. Rise up with your captives, your wives and children, and settle down in another place! So long as you are at enmity with the king of Hatti, exercise your hostility from some other country! From my country you shall not conduct hostilities. If your heart is in the land of Karkiya or the land of Masa, then go there!’”

In conclusion Hattusili asked the Ahhiyawan king to inform Piyamaradu that “the king of Hatti and I, in that matter of Wilusa over which we were at enmity, he has converted me and we have made friends; a war would not be right for us.” Hattusili then apologized for any aggressive actions he had taken against Ahhiyawa, ascribing his actions to the hotheaded impetuousness of youth: “At that time, my brother, I was young; and if at that time I wrote anything insulting it was not done deliberately. Such a remark may very well fall from the lips of a leader of troops, and such a man may very well chide his men if in a battle anyone is idle or cowardly.”

The Hittites were assiduous chroniclers of their history and the 13th century bc was, to say the least, extremely eventful, providing the royal scribes with much to write about. One may fairly assume that they were kept quite busy in this regard. The absence of clay tablets bearing their compilations should not be construed as an abandonment of their endeavors. Such tablets were certainly made, and although most were probably lost in the destruction of the Hittite empire at the end of the Bronze Age, some surely still exist, buried in the Anatolian subsoil awaiting discovery. Until their unearthing, however, we must rely on conjectures based on and supported by what we already know about Piyamaradu and by known developments in the Near East in his lifetime.

We may well assume, for instance, that he continued harassing the Hittites until he died, or was slain in combat, or grew too enfeebled to do what Homer called the “hard work of battle.” Piyamaradu lived a long and full life spanning the reigns of three Hittite emperors, and he was a torment to each. He was, by turns, a renegade, a warlord, a pirate, and, for a time, the ruler of a sizable realm in Western Anatolia, with Troy as his capital. His actions involving that city surely constitute a literary cornerstone for stories about the Trojan War, including the Iliad and the Odyssey. For that reason he must be counted as an important contributor to the cultural patrimony of Western civilization.

The fact that he is largely unknown outside scholarly circles does not diminish his importance. “Many brave men lived before Agamemnon,” Horace tells us in one of his Odes, “but they are all bound, unknown and unwept in the long night, for there was no one to sing of them in sacred verse.” The poet might have been writing about Piyamaradu.

Steven Weingartner is editor of the Cantigny Military History Series and author and editor of books and articles on military affairs and related topics, including Lala’s Story: A Memoir of the Holocaust (Northwestern University Press, 1997). This article was derived from a longer piece that includes more material on military organization and tactics. He can be contacted through Military Heritage.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments