By Kelly Bell

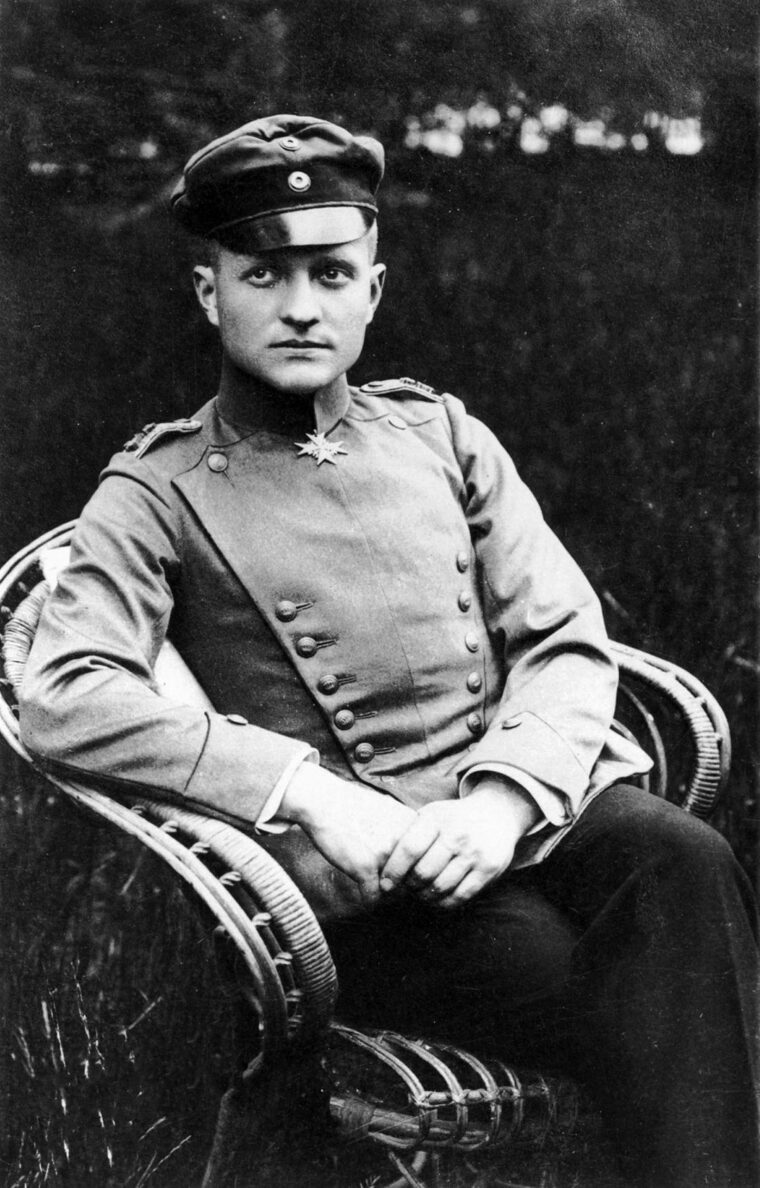

Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen was born May 2, 1892, as the second of four children to Baron Albrecht and Kunigunde von Richthofen. With veins full of aristocratic blood he enjoyed a life of privilege growing up in Silesia. At 11, he entered the Prussian military school Wahlstatt near Liegnitz. He was an excellent student and graduated as a cavalry officer cadet in 1911. Commissioned as a lieutenant a year later, he was assigned to Kaiser Alexander III Uhlan Regiment #1 and posted to the frontier city of Militsch (now Milicz, Poland) northeast of Breslau. After almost three years of monotony he and his comrades were thrilled to learn of the outbreak of war late in the summer of 1914. They could hardly wait to mount their steeds and gallop into the midst of the Fatherland’s enemies as their noble ancestors had done for centuries. But by this time the Industrial Revolution had extended its reach into warfare, and he was transferred east to serve under Field Marshal August von Mackensen during the Gorlice-Tarnów Offensive of May/June 1915. For the first time he climbed into a cockpit.

In the autumn of 1915 he began training for single-seaters by flying with an instructor in a trainer two-seater that had pilot controls in both cockpits. The experienced airman in front of him could instantly correct any errors. An ignominious crash during his first solo flight only made him more determined to master this new mode of warfare. It took three tries, but he finally passed flight-testing on Christmas Day 1915.

Just before the Battle of the Somme he was again transferred east, missing the massive offensive by the British Royal Flying Corps that essentially drove the German planes from the sky over the western front. Again relegated to bombing and strafing, he killed great numbers of ground troops, but was unfulfilled. It was one-on-one fighting for which he yearned. And when he got his wish late in the summer of 1916, he flew into history.

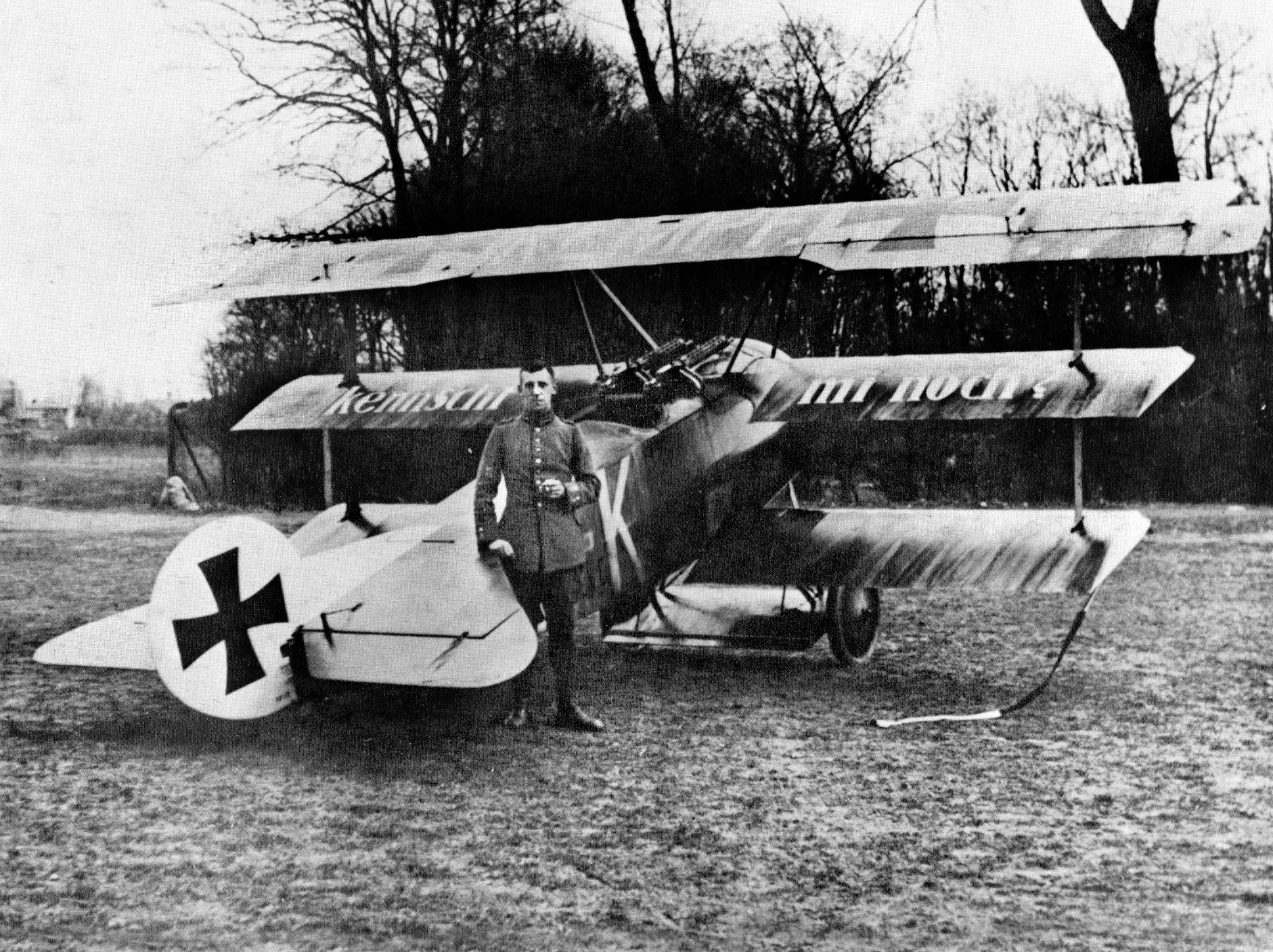

He was sent back to the western front where he joined Jagdstaffel #2 and, after extensive training in the new Albatross single-seater fighter von Richthofen and his fellow neophytes flew their first dawn combat patrol on September 17. Commanded by Capt. Oswald Boelcke, the Germans attacked a flight of F.E.2b two-man bombers from the Royal Flying Corps’ 11th Squadron. When von Richthofen tried to latch onto the tail of a bomber its observer sprayed him with accurate machine gun fire, forcing him to constantly dodge, and making it impossible for him to draw a bead on the English machine. Improvising, he flew into a cloud, executed a wide downward turn which brought him out of the overcast below and behind the bomber—whose crew assumed he had abandoned the attack and were flying straight and level. Flying in their blind spot, von Richthofen closed to just 30 yards when he raked the F.E.2b from tail to nose, riddling its engine and both crewmen.

German airmen quickly became familiar with the landscape and battlefields of the sprawling Battle of the Somme, and as the weather turned cold they and their new planes carved a swath through the previously dominant Allied air forces, but lost many of their own as well. On October 28 Boelcke was killed in a midair collision with one of his own men, and von Richthofen, who by then had six victories, took over command of Jagdstaffel #2, which the high command re-christened Jagdstaffel Boelcke. His capacity as a new commander would soon be severely tested by what was then the greatest air battle in history.

The four-month Battle of the Somme was grinding to a conclusion on the morning of November 9, 1916. But for the more than 100 men in 80 aircraft the world’s biggest aerial clash was just beginning. Shortly after 8 a.m., 16 British bombers, escorted by a squadron of fighters, took off en route to the large German supply depot in the occupied village of Vraumont. Realizing the perfect flying weather would bring Allied planes out in force, the Germans also took off at full strength. Minutes later, the fleets made visual contact directly over the front. Closely followed by five of his pilots, von Richthofen charged the enemy. Two more flights of German planes flanked his little formation, but it was his flight, attacking from above and head-on, that opened fire first.

Von Richthofen quickly flamed a B.E.2c bomber, but he and his men could not deflect the Brits from their objective, and despite losing four planes from their formations they managed to drop 72 bombs on the vital Vraucourt supply dump. Still, as reward for downing a bomber before it could drop its load, and for his earlier victories, von Richthofen received from the Grand Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha the Bravery Medal of the grand duke’s duchy.

On November 23 the young man downed his most renowned adversary—British Major Lanoe Hawker, Victoria Cross. Although as commander of Royal Flying Corps Squadron 24 his administrative duties had kept him grounded for most of the war, Hawker’s infrequent forays into combat had been fruitful as he bagged seven Germans. After a dogfight lasting several minutes Hawker, noting that all his pilots had turned for home and left him alone over enemy lines, abruptly broke off his duel with von Richthofen, dove to 150 feet and made a full-speed break for home. Against anyone else this maneuver might have worked. Yanking his Albatross D.H. into a twisting dive the German squeezed off a brief burst at the Airco DH.2, and then pulled up hard to avoid crashing. One of the bullets passed cleanly through Hawker’s head. Although it was only his 11th kill, the status of his victim made the young baron famous.

The 24-year-old entered the new year as the soldier who had, through dogfighting, bombing and strafing, killed more of his country’s enemies than any other German. Early in the year he received the Pour le Merite and the Austrian War Cross from Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Josef. He saw his name in the headlines of German, French and British newspapers. It was at this point that, in order to insure his adversaries knew whom they were fighting (and perhaps be somewhat unnerved as a result) he had his Albatross painted a bright, garish red. He was now officially Der Rote Baron (Red Baron). In January he was assigned to command a new unit.

The outfit was Jadgstaffel 11, and although it had been formed at the same time as the Boelcke unit, it did not yet have a single victory. The upper echelons hoped someone of von Richthofen’s stature would turn this confidence-bereft gaggle into an effective fighting unit. It was a sound strategy.

Leading his new pilots into hostile airspace on January 23, he casually torched an F.E.8 single-seater reconnaissance plane. Over the next week he scored two more kills, and his new command began to suspect that if the CO could so easily down the enemy, so could they. Concentrating on attacking Allied formations from behind, the men of Jagdstaffel 11 began to specialize in picking off stragglers. On March 17, von Richthofen shot down his 27th and 28th victims. For this pilot his enemies now called “Little Red” (both for the color of his plane and for the blood he spilled) April 1917 would be the bloodiest month of all.

It was his performance during those 30 days that motivated Field-Marshal Erich von Ludendorff to proclaim that von Richthofen was “worth two divisions of German infantry.” The young man sliced a blazing swath through Allied air power throughout April, and his constantly improving pilots stayed right behind him as “Bloody April” became the most successful period the German air service enjoyed throughout the war. The Kaiser’s airmen downed four enemy planes for every one they lost. According to Imperial German records, they shot down 120 British planes while losing only 30 of their own. It would appear they were at least this successful, because British records report the Royal Flying Corps lost even more than this, with 151 of their aircraft listed as “missing” for April. Von Richthofen bagged 21 planes that month, wrapping it up in grand style by flaming four on the 29th alone and boosting his personal total to 52. It was time for him to take a rest.

Under direct orders from his superiors (who were worried his nerves might fray) to not fly anything while he was away from the front, von Richthofen went home to bathe in the acclaim of his adoring nation. Constantly fawned over by crowds of admirers composed mainly of besotted young women and hero-worshipping little boys he toured widely in Germany, receiving as a 25th birthday present a private lunch with the Kaiser on May 2. He had a reunion with his beloved mother (his father was serving at the front) in his hometown of Schweidnitz, was received by Field-Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, and savored his long-neglected passion for hunting, tracking and shooting wild boar in the Black Forest. By the time he returned to the front in June the Allies, during the Battle of Messines, had managed to wrest air superiority from the Germans. Flying newer Bristol and S.E. 5 single-seater fighters and D.H.4 two-seater fighter-bombers, they were shifting the balance of power back to their side. It would not take long for von Richthofen to learn how dangerous his enemies had become. The Red Baron was shot down on July 6.

On that morning von Richthofen led his Albatrosses to intercept a flight of six F.E.2 reconnaissance planes of the Royal Flying Corps’ No. 20 Squadron. He drew a bead on a plane flown by Capt. D.C. Cunnell, whose observer/gunner was 2nd Lt. A.E. Woodbridge, who already had his machine gun red-hot. By his own account and by those of some of his comrades in the other British planes, Woodbridge had already shot down four Germans before the baron targeted his machine. Although he did not know it at the time, the man Woodbridge next trained his gun on was Manfred von Richthofen.

“I recall there wasn’t a thing on that machine that wasn’t red, and God how he could fly!” Woodbridge would recall 10 years later. “I opened fire with the front Lewis, and so did Cunnell with the side gun. Then something happened. We could hardly have been 20 yards apart when the Albatross pointed her nose down suddenly—Zip, and she passed under us!”

Cunnell and Woodbridge saw the red plane slip into a tailspin, but were too busy to watch to see if it crashed. They eventually machine gunned their way out of the massive dogfight and returned to their airfield.

One of Woodbridge’s bullets had grazed the left side of von Richthofen’s head, knocking him unconscious. He fluttered down approximately 10,000 feet before coming to and realizing to his horror he was completely blind. Still, he managed to control his tailspin and bring his plane into a gentle downward glide. After a few moments his vision returned somewhat and he was able to steer eastward, but was steadily growing weaker and knew he had to land immediately. He managed to put down safely beside a road. Struggling from the cockpit he tumbled headfirst into some briars, but a German patrol came to his assistance and radioed for an ambulance that carried him to a military hospital in Courtrai.

In a letter to his mother he wrote: “I had a good-sized hole—a wound of about 10 centimeters in length. At one spot as big as a dollar. The bare, white skull bone lay exposed. My thick Richthofen skull proved itself bullet-proof.”

Although he tried to make light of his situation, the Red Baron was a sick and unhappy man during his stay at Courtrai. His injury was serious, and he doubtless reflected on the implications of Woodbridge’s bullet having struck an inch or two to the right. That cartridge had shattered his youthful sense of invulnerability, and he was fearful for his country as well. He had seen the first traces of the growing American involvement, and was starting to wonder if maybe Germany had too many enemies. Plagued by agonizing headaches he was unable to hide his weakened physical and emotional condition from his mother. Years later she described how her son was never the same after his injury.

“Manfred was changed after he received his wounds. His fears for [his younger brother] Lothar’s safety increased, and he was no longer certain victory would come to our side. He said that people in Germany did not realize the power of the Allies as well as did the men who had to face their forces at the front.”

Von Richthofen endured repeated procedures to remove sharp bone splinters from his cracked head and, given the medical technology of 1917, these episodes were excruciating. Still, he was away from the front just three weeks. Although offered a ground job upon his return, he refused, stating that since German infantrymen had to go back to front-line duty after recovering from non-crippling wounds he felt obliged to do the same.

As in any military unit in the thick of constant fighting, three weeks is a long time, and again the young, newly promoted captain returned to find many strangers in his squadron’s ranks, and many friends gone forever. He was placed in command of the entire squadron, with four (and sometimes five) Jagdstaffels under his authority. Being responsible for so many men in the air was a distraction, and although he still had quite a few planes to shoot down, he was no longer in his prime.

He downed three Englishmen in August while flying a brand-new Fokker tri-plane whose performance was exemplary, unfamiliar to the British and hence doubly dangerous. On September 3, he had an exhilarating dogfight with a single-seater Sopwith. After lengthy combat the British pilot ran out of ammunition. Pinned between von Richthofen and the ground, the Englishman deliberately crashed into a tree to avoid being shot down. He emerged from the wreckage uninjured to become one of the few men to survive combat with the Red Baron. It was his 61st victory, and he was given a special leave to go to East Prussia to hunt elk.

It was nearly three months before von Richthofen shot down another plane. After returning from leave he found himself so often directing operations both while on the ground and aloft that he had fewer opportunities for his preferred one-on-one combat. On November 23, he shot down his 62nd and downed number 63 one week later. It was time for a long hiatus as freezing, stormy weather socked in the western front, grounding all air services. It was March 12 before the Red Baron scored his 64th kill. The next morning he got his 65th while driving off several planes that were attacking Lothar. Severely wounded, the younger von Richthofen brother crash-landed and spent the rest of the war hospitalized. He finished his combat career with 40 victories.

Over the next three weeks Manfred ignored his awful headaches, fought madly and with abandon as he dared to hope Germany might still see victory. On April 20, 1918, the day an obscure Austrian Gefreiter named Adolf Hitler turned 29, the Red Baron shot down two of the Allies’ dread Sopwith Camels, bringing his score to 80.

Late the following morning von Richthofen and nine of his pilots lifted off from their airfield outside the French village of Cappy. At midday they spied two Allied reconnaissance planes 2,000 feet below them. As they dove to attack, 10 Sopwith Camels of the Royal Air Force’s #209 Squadron intercepted them and a wild aerial melee ensued.

Von Richthofen fastened onto the tail of a Camel flown by Lt. W.R. May, who had ducked out of the battle and was headed westward for home. Canadian Capt. Roy Brown noticed the all-red Fokker triplane chasing May and yanked his own Camel around to go to the rescue. Von Richthofen, his guns blazing furiously, followed May deep into Allied airspace and to a steadily lower altitude. Apparently fixated on his target (whom he had already wounded in the right arm) he did not appear to notice Brown diving on him from the rear. Leveling off just above the treetops Brown opened fire at a range of 100 yards at the same time a machine gunner on the ground commenced shooting at von Richthofen. Brown watched his tracers stitch seams in the right side of the Fokker, which wavered, stopped shooting and went into a shallow glide, landing intact in a field outside the village of Sailly-le-Sec.

Australian infantrymen cautiously approached the plane and noted that the man in the cockpit, although still clutching the joystick, was dead. A single bullet had passed completely through his upper body from left to right. Easing the corpse from the plane the soldiers searched it for identification and found papers bearing name and rank.

“My God! It’s Richthofen!” gasped one of the muddy foot sloggers.

a bullet during a dogfight on July 6, 1917.

“Christ! They got the bloody baron!” another shouted to his comrades back in the trench.

There were those who later proposed the ace’s head wound of the previous summer was what got him killed. During his last months he exhibited some symptoms that could have been caused by brain damage. After returning from the hospital some of his men thought he had become distant, unemotional and humorless. There is no denying that his actions on his last flight were almost suicidal as he suffered apparent target fixation, failing to look behind him as he chased a plane and allowed Brown to easily get on his tail, flying alone deep into enemy territory, and at such low altitude he was seriously vulnerable to ground fire. He was not likely to have committed such blatant errors had he beed lucid.

One of his young officers, Hermann Göring, took over command of Jagdstaffel 11.

While the Allied world exulted, Brown was overcome by what he seemed to have accomplished, collapsing later in the day from stomach pains aggravated by nervous tension. For three weeks he lay delirious in a field hospital, and six weeks after his dogfight with the baron his superiors decorated him with a Distinguished Service Cross and transferred him back to England to serve as a flight instructor. The following autumn he fainted while at the controls of a plane and was nearly killed in the crash. Although he survived, he never flew again.

The credit for killing von Richthofen seems to have almost killed Brown. Ironically it would appear to have been undeserved. Later researchers pointed out that the fatal bullet came from the left. The one burst Brown fired into the Fokker triplane was from the right. It appears the nondescript foot soldier blazing away with a Lewis machine gun was the actual killer of Capt. Manfred von Richthofen. His name was Snowy Evans, and he mustered out of the British Army at war’s end. Seven years later, a homeless derelict, he froze to death on the streets of London.

In the next war Germany spawned other aces who far surpassed the Red Baron’s 80 victories, but none of them ever became a household name—featured in songs, endless books and even comic strips. It’s the trailblazers that are always remembered and von Richthofen was the first great soldier-hero of the sky.

I once met an elderly ex pilot (Munro) who had been serving in the Australian trenches prior to flight training. He saw Richthophen crash within a hundred yards of his trench and he was was emphatic that he was hit by ground fire. (Yes- I had to ask!). As I remember, Brown, in his combat report, said that he had “fired at” a red triplane which then dived away, not that he had hit the aircraft.

I saw a documentary, just a few years ago, that had an analysis of the trajectory of the single .303 round that entered the baron’s body under the left armpit, travelled more or less upwards and cut a vital artery to the heart. The significance of the artery wound was that the victim had a very short remaining life, just enough to land straight ahead (he was on the deck) and take his last breath as the first Aussie reached him. The documentary analyst said something to the effect “.. there was a .303 weapon on the ground at a certain distance and at a certain direction..”

It has been said that the publicity machine of the RAF put out the misinformation about Brown’s victory. He would never dicuss the matter.