By Patrick Reynolds

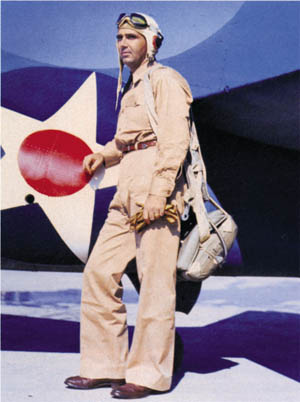

Edward Henry “Butch” O’Hare rocketed to fame in February 1942 by singlehandedly taking on eight Japanese torpedo bombers bent on destroying the aircraft carrier USS Lexington and shooting down several of them. For this deed, President Franklin D. Roosevelt decorated him with the Medal of Honor. Just 21 months later, he was dead, killed off the Gilbert Islands in the Central Pacific while engaged in night-fighting combat.

To honor his sacrifice, one of the world’s busiest airports, Chicago’s O’Hare International, was named after him. It’s a constant reminder of who Butch O’Hare was and the sacrifice he made.

Butch, however, was not the first in his family to create headlines. His father, Edward “E.J.” O’Hare, first the owner of a trucking company and later an attorney, was gunned down in 1939 on orders from infamous Chicago mobster Al Capone.

As president of Sportsman’s Park, a now vanished Cicero racetrack just outside Chicago’s western limits, E.J. was privy to many of Capone’s illegal activities because Capone and his associates were also entwined in the operation of the racetrack. From 1930 to the time of his death, E.J. was an active undercover participant in the Treasury Department’s investigation and conviction of Capone on charges of tax evasion. Capone eventually learned of E.J’s role, which cost him his life.

Although E.J. lived in Chicagoland for many years, St. Louis was home for Butch while growing up. With him were two sisters, Patsy and Marilyn, and mother Selma.

When he was 13, Butch was whisked across the Mississippi River to Alton, Illinois, and Western Military Academy, a private military school about 25 miles from St. Louis. Interestingly, among his best friends there was Paul Tibbets, who later became the U.S. Army Air Forces colonel who dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Holidays and summers Butch spent back home in Missouri, where he continued practicing hunting and shooting—skills that would one day serve him well. By the age of 15 he had had his first experience with flying, as E.J. arranged to get him into a plane and even spend some time handling the controls.

The five years he spent at Western Military Academy were, by all accounts, good ones. His grades were solid, he played some football, and he was an excellent swimmer. He also began to shed some of the shyness and lack of self-confidence that had worried his parents when they first chose to send him to the academy.

In September 1932, E.J. and Butch’s mother Selma divorced. By that time E.J. had become part of the horse racing business in Chicago. Much of his time had to be spent there, and Selma wasn’t well suited to that life.

Speculation has centered on exactly what caused E.J. to put his life at risk to help the Treasury Department go after Capone. E.J.’s connection to the Feds was through Frank Wilson, a Treasury Department official loaned in 1928 to the Criminal Investigation Division of the IRS for the purpose of investigating Capone. By 1930, E.J. was providing Wilson with information that led to Capone’s conviction. In fact, once Capone died in prison in 1947, Wilson stated openly, “On the inside of the gang I had one of the best undercover men I have ever known: Eddie O’Hare.”

Some have also speculated that E.J. worked with the government to avoid having his own less than squeaky clean income tax situation investigated. Another theory is that by helping put Capone in jail, E.J. would be removing from his own racetrack business a man known not only for illegal activities but also behavior as heinously violent as Chicago’s 1929 St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.

One other thing about E.J. should be stressed. He did not want his son to follow in his footsteps in the gaming business. Noting that by the time Butch was graduating from the Western Military Academy the boy had begun to show a keen interest in flying, E.J. did everything to leverage this passion in any way he could.

E.J. was no doubt pleased when, in 1932, Butch applied to the U.S. Naval Academy and passed his entrance tests on his second try. On June 3, 1937, he graduated, ranking 255th out of 323. Few knew that World War II was around the corner, and who could have guessed that 41 members of the Class of 1937 would lose their lives in that conflict?

In Butch’s first assignment, he spent two years aboard the battleship USS New Mexico (BB-40) before heading off for preliminary flight training. He was stunned when he was informed that his father had been shot to death while driving his car in Chicago on November 8, 1939, most likely by Capone’s gunmen.

By 1940, when he was assigned to the Naval Air Station at Pensacola, Florida, to train in Naval Aircraft Factory N3N-1 “Yellow Peril” planes and Stearman NS-1 biplane trainers, one thing was becoming abundantly clear: Butch O’Hare excelled at aerial gunnery.

When he was assigned to the fighting squadron VF-3, his commander was Lt. Cmdr. John (Jimmy) Thach, one of the Navy’s top airmen. Thach had come up with something called the “Bitching Team,” which consisted of a group of VF-3’s most highly skilled and experienced pilots.

One of these aces would take a newcomer into the air for a mock dogfight. Thach’s experience had taught him that the best approach was to gain altitude and then swoop down on an opponent’s tail, where he could home in for the kill. Few rookies mastered this skill quickly, but when Butch was so tested, by Thach himself no less, the rookie won the day. Thach was so impressed that he made Butch part of the Bitching Team.

Under Thach’s tutelage, Butch’s skills grew rapidly. Thach was greatly impressed by what Butch was able to get a plane to do. “He didn’t try to horse it around,” said Thach many years later in an oral history recording. “He learned a thing that a lot of youngsters don’t learn[:] that when you’re in a dogfight with somebody, it isn’t how hard you pull back on the stick to make a tight turn to get inside of him, it’s how smoothly you fly the plane.”

Thach attributed it to Butch’s acute and innate sense of timing and relative motion. Thach also admired Butch’s eagerness to read anything he could lay his hands on that might help him in aerial gunnery and his quick understanding of what he read. As Thach put it, “Butch just picked it up faster than anyone else I’ve seen.”

Apparently that wasn’t the only thing he did with remarkable celerity. On July 21, 1941,while at the hospital to visit a friend whose wife had just given birth, Butch met Rita Wooster, a nurse attending the new mother. When Rita’s shift ended, Butch drove her home. Upon arrival, he asked her to marry him. She pointed out that they’d only met that day, that she was several years younger, and that he wasn’t a Catholic as she was. None of it mattered, he replied, adding that he’d take instructions to convert. Six weeks later, they were married.

Three months after the nuptials, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. On the morning of December 8, 1941, Butch and the rest of VF-3 were on their way to Hawaii to learn how and where they’d be deployed now that war had begun.

By mid-December they were onboard the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga (CV-3) headed west for Wake Island as part of Task Force 14. VF-3’s first loss occurred on December 22, when a plane piloted by Lieutenant Victor M. Gadrow had engine trouble that led to his crashing and sinking in rough seas.

A few days later, TF-14 was recalled to Pearl, so Butch and company saw no action at Wake Island. By December 31, the Saratoga was back at sea and heading west. That trip was cut short the evening of Sunday, January 11, 1942, when a Japanese torpedo struck the Saratoga. She was able to limp back to Pearl, but she was no longer part of the Butch O’Hare story. VF-3, with a full complement of 18 Grumman F4F Wildcats, was now attached to the “Lady Lex”—the aircraft carrier USS Lexington (CV-2).

On January 31, 1942, the Lexington was sent south as part of Task Force 11 under Vice Admiral Wilson Brown, Jr. VF-3 suffered its second fatality onboard the Lexington on February 8. Edward Frank Ambrose was crushed due to a malfunction in a block-and-tackle arrangement used to start the fighter planes’ engines.

February 13 saw the Lexington in the Solomon Islands in the Southwest Pacific, and Butch expected to be on combat air patrol shortly. But while some members of VF-3 were indeed sent airborne, including Thach, Butch’s orders were to stay in reserve. Thach downed a Japanese reconnaissance plane, as did Burt Stanley, another member of VF-3. Back onboard the Lexington, they described to their squadron comrades what VF-3’s first two kills had been like. According to Thach, Butch, having been kept in reserve so far, was pretty much fit to be tied.

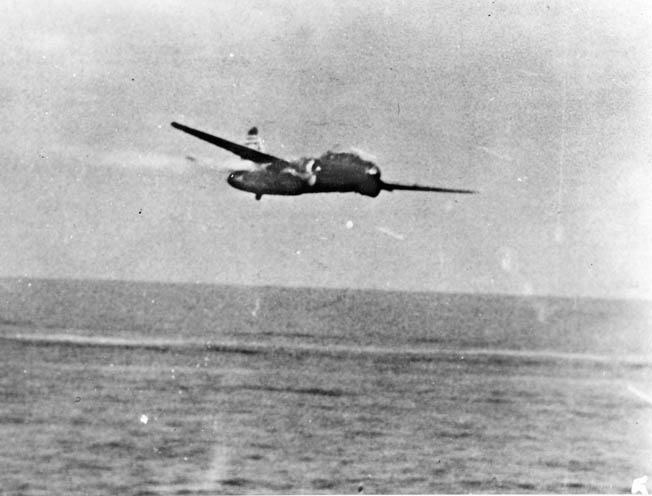

O’Hare got his chance on February 20 when 17 medium bombers of Japan’s Fourth Air Group were sent in two groups (Chutai) to attack Task Force 11. These land-based torpedo bombers from the base at Rabaul, Papua New Guinea—nine in Chutai Two and eight in Chutai One—were Mitsubishi G4M1 attack planes, one of Japan’s most modern aircraft at the time. Characterized by a relatively fat fuselage and wide wings that came to an abrupt point, this was the plane that the U.S. Navy called a “Betty.”

At 3:42 pm on the day that Butch O’Hare made history, the radar systems of Task Force 11 detected the approaching Japanese Bettys. The nine-plane Chutai Two attacked first, and between 4:39 and 4:43 pm Wildcat pilots launched from the Lexington had eliminated five of the nine Bettys.

The pilot of one of the crippled torpedo bombers tried to crash his plane onto the flight deck of the Lexington, but 1.1-inch cannons and .50-caliber machine guns on the carrier helped make sure that didn’t happen.

Vice Admiral Brown said the concentrated fire nearly tore pilot and plane to pieces. “And as the plane swung by,” wrote Brown in his unpublished memoir, “only a few yards from where we stood, we saw that the pilot was dead, slumped at the controls, as he plunged into the sea.”

It was 4:46 when Butch was launched during the enemy’s aerial assault, and he couldn’t help but wonder if his carrier would still be afloat when he returned. Once aloft, he swiveled his head all around, amazed at the number of American planes dashing around him. He worried that the fight would be over before he could get a shot off.

So, along with another VF-3 Wildcat piloted by Duff Dufilho, he climbed to an altitude high above the ships and assumed combat air control position. At 4:49, right about the time the wounded Betty from Chutai Two tried but failed to crash onto the Lexington’s flight deck, the carrier’s radar detected Chutai One about 30 miles north-northeast and sent up a radio message warning of the threat.

Unfortunately, because all the other fighters had flown southwest to pursue what remained of Chutai Two, Butch and Dufilho were the only two fighters available to take on this new threat. So the two pilots positioned their F4F Wildcats between the Lexington and the incoming Bettys.

Butch test fired his four .50-caliber Browning machine guns, and all was fine, but Duff’s were jammed. O’Hare gestured to Dufilho to return to the carrier, but Duff refused, even though he knew he would only be a decoy in the upcoming fight.

With the eight Bettys less than 12 miles away from the Lexington and closing fast, Butch and Dufilho had an altitude advantage of about 1,000 feet. They also had with them the element of surprise, as the Japanese didn’t know they were there. But still, one armed fighter against eight enemy bombers?

Keep in mind, too, that in addition to carrying torpedoes, the Bettys—like American B-17s and B-24s—were bristling with firepower. There were a dozen 7.7mm Type 92 machine guns in each bomber, plus a 20mm Type 99 cannon in the tail.

It mattered not to Butch. “There wasn’t time to sit and wait for help,” he’s quoted as saying in Queen of the Flattops, a 1942 book by Chicago Tribune correspondent Stanley Johnston. “Those babies were coming on fast and had to be stopped.”

And stopped they were, thanks largely to four remarkable passes made by Butch. In each pass—termed by combat aviators a “high-side run”—he descended from above, fired bursts as short as possible to conserve ammunition, and then climbed back above the V formation of enemy bombers to begin another pass.

As crucial as piloting skills and sheer bravery were in this dogfight, being able to shoot accurately and efficiently trumped everything. Butch’s four guns each held about 450 rounds, which meant he had enough ammunition to fire for a grand total of about 34 seconds.

In his first pass he aimed for the trailing bomber on the right side of the V formation, firing into the right engine. Both the fuselage and a fuel tank were struck, and the surprised pilot fell out of formation to the right, streaming smoke. Next Butch aimed at the adjacent bomber on the right side of the V, this time igniting the plane and causing it, too, to fall out of formation to the right.

Pleasantly surprised that his first aerial combat had gone so well, he looked around for Duff but didn’t see him. It turns out that Dufilho had followed Butch into the battle in the hope of drawing some of the fire away from Butch. Like Butch, he survived the battle. He died the following August in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons.

Though these two Bettys were forced out of the attack formation, it turned out that they were not out of the fight. Both managed to recover sufficiently to later drop their bombs. This hardly mattered to Butch at the time, as he explained in a March 30, 1942, radio broadcast: “When one would start burning, I’d haul out and wait for it to get out of the way. Then I’d go in and get another one. I didn’t have time to watch [them fall]. When they drop out of formation, you don’t bother with ‘em anymore. You go after the next.”

symbolic of his first five “kills.”

Now it was time for Butch’s second pass, and this time he targeted the far left Betty in the attack formation. Again he aimed for the right engine, and again his aim was true. The third Betty dropped out of the formation and dumped its bombs harmlessly.

Still in his second pass, Butch now maneuvered into point-blank range and fired into the cockpit of one of the Bettys in the center of the V formation. This time his victim splashed into the sea. By now Butch and his airborne adversaries were so close to the Lexington that a whole new challenge presented itself: the 5-inch antiaircraft guns of Task Force 11.

Unfazed, Butch climbed above the Japanese bombers to make his third pass. Again he managed to splash one of the bombers, leaving exposed the lead bomber of the formation. Targeting its left wing, Butch fired so accurately that he shot the engine right out of the plane. Fatally damaged, it spun out of the formation and into the ocean.

Still not finished, Butch gained altitude again to make his fourth and final pass. But after firing 10 rounds he was done, all 1,800 bullets fired. So he climbed above the bursting antiaircraft fire and away from the fray. At this point there were still five of Chutai One’s original eight Bettys in the air.

By the time the battle was over, a total of six 250kg torpedoes were aimed at the Lexington. Not one hit its mark. In fact, of the 17 Japanese bombers that had left their base that day in Rabaul, only two made it back. Japan’s Combined Fleet headquarters was appalled at these losses, which wound up having hugely negative strategic implications for future combat.

As for Butch O’Hare, it was time to return to the Lexington. As he prepared to land, a nervous and obviously confused Lexington gunner opened fire on Butch’s Wildcat with a .50-caliber machine gun. Fortunately, he missed.

According to Thach’s oral recording, Butch later encountered the embarrassed young gunner and said, “Son, if you don’t stop shooting at me when I’ve got my wheels down, I’m going to have to report you to the gunnery officer.” Later, said Thach, Butch added, “I don’t mind him shooting at me when I don’t have my wheels down, but it might make me have to take a wave-off, and I don’t like to take wave-offs.”

Examination of Butch’s plane after it landed revealed that it had received minor damage from antiaircraft shell fragments, but only one enemy bullet had reached him, striking his right wing.

What he accomplished in just under four minutes above the Lexington would have been remarkable for even the most experienced and battle-hardened veteran. But this was O’Hare’s first combat experience!

And what did he make of it all? A reporter for the Washington Times-Herald captured this quote from Butch for a June 9, 1942, story: “It was just careful timing. You don’t have time to consider the odds against you. You are too busy weighing all the factors, time, speed, holding your fire till the right moment, shooting sparingly. You don’t feel you are throwing bullets to keep alive. You just want to keep shooting. You’ve got to keep moving. When you’re sitting (and you do have to sit to fire) you’ve got to get your shots off and then move again. The longer you sit, the better chance you’ve got to get hit.”

Butch participated in just one more combat mission, the March 10, 1942, raid on Lae-Salamaua in Papua New Guinea, before Task Force 11 and the Lexington headed back for Pearl Harbor. Butch would not return to combat for another 18 months, as the Washington brass decided that his recent heroics made him more valuable in PR and pilot training roles than in the role of a fighter pilot.

On April 15, 1942, amid rumors of a Medal of Honor being headed his way, Butch boarded a plane from Pearl Harbor to San Francisco, where he’d soon be reunited with wife Rita, mother Selma, and all the rest of the family. On the same day, many of his VF-3 comrades sailed aboard the Lexington on what proved to be her final cruise. Three weeks later, in the Battle of the Coral Sea, she became the first U.S. carrier lost in World War II.

Official confirmation for Butch’s Medal of Honor came on April 16. Three days later, Butch and Rita arrived in Washington to face the media ahead of the April 21 meeting with President Franklin D. Roosevelt during which the medal would be bestowed.

In Fateful Rendezvous: The Life of Butch O’Hare, Steve Ewing and John B. Lundstrom’s outstanding 1997 biography of O’Hare, the authors wrote, “As he was shuttled from one group of VIPs to another, Washington’s ‘take’ on Butch was that he was modest, somewhat embarrassed by all the flap, handsome, and very nice, and although not overly articulate, he nonetheless conveyed humor. His favorite comment was that he hoped his next aerial combat would not take place in front of an audience, such as the one on the Lexington, so that he would not again become ‘cannon fodder for the press.’”

On the morning of Tuesday, April 21, Butch and Rita were presented to President Roosevelt, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, assorted admirals and politicians, and members of the press. First Roosevelt informed Butch that he had been promoted to the rank of lieutenant commander.

Roosevelt then moved on to what he described as the more important part of the ceremony. Using all the rhetorical flourish for which he was famous, the president proceeded to read the Medal of Honor citation:

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in aerial combat, at grave risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty, as Section Leader and Pilot of Fighting Squadron Three, on 20 February 1942. Having lost the assistance of his teammates, Lieutenant O’Hare interposed his plane between his ship and an advancing enemy formation of nine attacking twin-engined heavy bombers.

“Without hesitation, alone and unaided, he repeatedly attacked this enemy formation at close range in the face of intense combined machine-gun and cannon fire. Despite this concentrated opposition, Lieutenant O’Hare, by his gallant and courageous action, his extremely skillful marksmanship in making the most of every shot of his limited ammunition, shot down five enemy bombers and severely damaged a sixth before they reached the bomb release point.

“As a result of his gallant action—one of the most daring, if not the most daring single action in the history of combat aviation—he undoubtedly saved his carrier from serious damage.”

In fact, Butch had faced not nine heavy bombers but eight; some fog-of-war type details were still being sorted out when the citation copy was composed. It is also unlikely that Butch actually “shot down five enemy bombers.” After all relevant records are examined, it appears he actually splashed three bombers during the dogfight and heavily damaged three others. The fact that he single-handedly saved the Lexington from serious damage is beyond dispute.

After Butch and Roosevelt shook hands, the president, sitting in his chair, took the Medal of Honor from its case and asked Rita to put it around her husband’s neck. He then asked the new lieutenant commander what sort of improvements he thought should be made to the Navy’s fighters. Without hesitation, O’Hare said that he would like to see a plane that could climb faster than the Japanese Zero. O’Hare would get his wish; the Grumman Aircraft Engineering Company of Bethpage, New York, was already hard at work on one: the F6F Hellcat that would first see combat in August 1943. A more powerful 2,000 horsepower engine was also later introduced into the Hellcat. It would be in an F6F Hellcat that Butch would fight his last battle.

A rousing reception in St. Louis came on Saturday, April 25, 1942, when a huge crowd turned out to cheer for its native son. Proud mom Selma and sisters Patsy and Marilyn were naturally part of the parade. By now they were beginning to realize just what Butch had accomplished. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch proclaimed in a banner headline, “60,000 GIVE O’HARE HERO’S WELCOME HERE.” He was, indeed, a national hero.

In the ensuing months, appearances before aviation cadets at Norfolk, Miami, Corpus Christi, and Jacksonville followed. It was usually a matter of making a patriotic speech and pushing war bonds. Still pretty much shy and retiring, “the uncomfortable hero” as Ewing and Lundstrom put it, Butch hated every minute of it, referring to it as “the dancing bear circuit.” But apparently he saw it as his duty and soldiered on. Besides, Washington wasn’t about to have it any other way. Few things had gone right for America in the war up to this point, so now that a genuine hero and a positive story had emerged it was an opportunity to be seized, and seized aggressively.

Finally, by June 1942, Butch was headed back to Pearl Harbor, where he would take command of VF-3. Training now became his primary responsibility, and though he worried that his relative lack of seasoning and experience might be a liability, he devoted himself to the task at hand. By all accounts he excelled at it, not only by succeeding in getting his young fliers ready for the important battles that lay ahead in the South and Central Pacific, but also by earning the respect, loyalty, and friendship of just about everyone he encountered.

On July 15, 1943, VF-3 was reconstituted as VF-6. Soon the pilots and their 36 F6F Hellcats found themselves attached to the light aircraft carrier USS Independence (CVL-22), from which they participated in attacks on Marcus and Wake Islands in August of that year.

On September 17, 1943, Butch was named commander of Carrier Air Group Six (CAG-6). He now oversaw the training and operational deployment of 100 pilots. But he never let his rise in rank go to his head. One of the fighter pilots under his command around this time described him as “a quiet, easy-going person with a delightful personality—aside from being a topnotch flyer.”

Andy Skon, a fighter pilot whose Hellcat would be along for the ride when Butch met his death, described Butch as “very much a flying CAG” who liked nothing better than to be aloft at the head of his air group.

As CAG-6, Butch now reported to the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6), the “Big E” and flagship of Rear Admiral Arthur W. Radford’s Task Group 50.2 during the American assault on the Central Pacific’s Gilbert Islands.

For Butch and the other fighter pilots launched from the Enterprise, strikes were focused on Makin Island, and everything seemed to go well. But as the dust settled, Admiral Radford was coming to the conclusion that the Japanese were now realizing how outmatched they were in trying to attack the American naval forces by day. He was convinced that Japanese air commanders would order night torpedo strikes, and he was determined to create an effective deterrent.

The strategy they came up with, and Butch played a central role in devising it, was something of a three-legged stool: ship’s radar, radar on board a Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bomber, and firepower from two F6F Hellcats. It all hinged on ship-mounted radar first detecting bogeys at considerable distances and then launching a TBF Avenger and guiding it to the bogeys by way of ship-to-plane radio communication.

The TBF Avenger also had radar, but it was far less powerful and was only useful to a distance of about six miles. So the idea was for the Avenger to piggyback on the robustness of the ship’s radar so that the Avenger could be positioned within striking distance of the bogeys. Two Hellcats would also be launched, and they would use radio communication to rendezvous with the TBF Avenger. Once the Avenger’s radar determined that the bogeys were within striking distance of the Hellcats, the Avenger would peel off, and the six .50-caliber machine guns of the Hellcats would neutralize the bogeys. It sounded simple, but was actually extremely dangerous.

By November 24, Radford ordered two three-plane night-fighting units—dubbed “Black Panthers” by Butch—into action at 3 am about 75 miles east of Makin. Needless to say, Butch was in one of the F6F Hellcats. While no encounter with the enemy ensued, it marked the first time in history that a night-fighter mission had been flown from an aircraft carrier.

Two nights later, on November 26, as reports came in to Radford that a night torpedo strike was imminent, he pondered if it was time to launch the Black Panthers for a second mission. From Radford’s memoirs: “On the bridge, as I decided what to do, Lieutenant Commander O’Hare approached me and requested that I send one of the Black Panther groups out.” Radford agreed.

At 5:45 pm, the “Pilots, man your planes” order rang out from the ship’s squawk box. A story in the Honolulu Advertiser said, “Stocky Butch was pulling on his helmet over his close-cropped black hair. He had widened a bit in girth in recent months, but the extra poundage had not lessened his ability to fly a Hellcat. One of the pilots shouted, ‘Go gettem, Butch.’ O’Hare’s reply was a grin. Then he dashed up a ladder to the flight deck.”

The idea was to intercept the Japanese night-strike group and then land either back on the Enterprise or at Tarawa atoll. Only one of the three-plane night-fighting units was to be launched. Butch and Andy Skon each piloted an F6F Hellcat. At the controls of the TBF Avenger was Lt. Cmdr. Phil Phillips, and joining him were gunner Alvin Kernan and Lieutenant Hazen Rand on radar.

O’Hare knew the mission was dicey and told Phillips that it was likely they wouldn’t make it back to the carrier, but would try for Tarawa instead. He told Phil, “We’ll be lucky if we even find the damned place.”

And so it was that at 6 pm on November 26, 1943, Butch’s Black Panther unit was airborne. The original plan to have all three planes united before attacking any Japanese aircraft was altered when the Command Information Center (CIC) sent Butch and Skon chasing after Japanese surveillance planes spotted on the Enterprise’s radar screen. Within an hour or so, having had no success in locating these planes, the two Hellcats went in search of the Avenger piloted by Phillips.

The rendezvous of the three planes was guided by radio communication from the Enterprise’s CIC, and by 7:25 the Avenger and the two Hellcats were finally united in the formation that had been originally planned: Avenger in the lead and Hellcats trailing left (Skon) and right (Butch). After the war, Kernan published his memoir titled Crossing the Line, in which he describes this final glimpse of Butch: “Canopy back, goggles up, yellow Mae West, khaki shirt, and helmet, Butch O’Hare sat aggressively forward, looking like the tough Navy ace he was, his face sharply illuminated by his canopy light for one last brief instant.”

To successfully complete the rendezvous of the Black Panthers, both Butch and Phillips had to turn on some combination of their planes’ running lights or recognition lights. Unfortunately, the lights didn’t go unnoticed by a Japanese Betty trailing the three American planes. It pounced.

“The long black cigar shape came in on the starboard side of the group across the rear of O’Hare … and began firing,” wrote Kernan, who had as good a view as anyone because he was facing backward in the turret of the lead plane. ‘Butch, this is Phil. There’s a Jap on your tail. Kernan, open fire.’

“I began shooting at the Betty. The air was filled with streams of fire, and a long burst nearly emptied my ammunition can. The Betty, as the tracers arced toward him, continued firing and then abruptly disappeared into the dark to port. I thought I saw O’Hare reappear for a moment, and then he was gone. Something whitish gray appeared in the distance, his parachute or the splash of the plane going in. Skon slid away. I thought that the Jap had shot O’Hare and then disappeared, but I also realized with a sinking feeling that there was a chance I might have hit O’Hare as well in the exchange of fire.”

At 7:34 pm, the Enterprise officially recorded that Butch was in the water. A desperate search that night by Phillips and Skon proved fruitless, as did a search the next morning by flying boats launched from Tarawa.

Deeply saddened at losing the skilled and universally popular Medal of Honor winner, Radford summed up the Black Panthers’ first night combat: “Believe our night fighters really saved the day. They mixed with the largest group, shot down two, and apparently caused great consternation. Had this [Japanese] group been able to coordinate their attacks with other groups, it would have been practically impossible to avoid all of them.”

No one will ever know for sure what happened to Butch that night, but Ewing and Lundstrom are convinced that he was not a victim of friendly fire. He was hit by machine-gun fire from the Betty, they believe. The authors also provide the following statistics to put Butch’s fate in context: “He was the first of seven carrier-based night-fighter pilots lost in combat, during which time the carrier night fighters flew 164 sorties, engaged the enemy on 95 occasions, and scored 103 victories.”

Among the tributes paid to Butch was the naming of the destroyer USS O’Hare (DD-889), launched in June 1945. But the biggest honor came in September 1949, when the Chicago-area Orchard Depot Airport was renamed O’Hare International Airport.

More than seven decades after Butch O’Hare’s exploits, many people—even those from Chicago—don’t know much, if anything, about the man for whom the airport is named. To help bridge this gap, in Terminal Two there is a display about the young pilot complete with photos, text, and an actual F4F Wildcat similar to the one flown by Butch. Used for training purposes over nearby Lake Michigan, it was restored after being recovered from the lake. Anyone passing through the airport who has an interest in history will want to stop at the display for a few moments and pay his or her respects to Edward Henry “Butch” O’Hare—an extraordinary man, pilot, and patriot.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments