By Keith Milton

Most history books teach that the War between the States began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate batteries ringing Charleston harbor fired on Fort Sumter and forced its surrender the following day. Actually, the Stars and Stripes was fired upon over three months earlier, on January 9, 1861, when the steamer Star of the West, under Federal charter, suffered hits from the same batteries that were to begin the war in April. The ship carried 204 Union troops along with their arms and baggage, and several tons of ammunition and provisions for the relief of Fort Sumter. She was, however, unarmed and unescorted, and was forced to stand out to sea to prevent her capture or destruction.

This overt act was swallowed by the U.S. government, at the time led by lame duck President James Buchanan, who was loath to do anything that the Southerners might view as provocative, and thus drive more states out of the Union. Up until the Star of the West incident, only South Carolina had seceded, but feelings were running high in Dixie and more states were expected to follow. This policy of indecision and failed reconciliation was to be partly responsible for giving the Southerners their most famous ship of war.

By the time president-elect Lincoln was sworn in on March 4, 1861, six more states had joined South Carolina and had formed the Confederate States of America. Five weeks later, Lincoln ordered the naval blockade of the South, and called upon the loyal states to furnish 75,000 militia to retake the Federal property seized by the Confederates. When Virginia and North Carolina refused to turn over the required regiments, Lincoln ordered the blockade extended to include those two states, even though they were still in the Union, and in spite of the fact that the Virginia legislature had passed a resolution of loyalty only two weeks before. This proved to be the last straw for the Virginians, and within a month they had joined the Confederacy, making their state the last to leave the Union.

At the outbreak of hostilities, the U.S. Navy was in bad shape. There were 90 ships on the list, but more than half were sailing ships 40 to 50 years old. They lay rotting in various yards and were used as receiving and store-ships and would be of little use in the war. Of the steam-powered vessels, 21 were on foreign station, several were in yards being overhauled, and the balance were smaller vessels, tugs, supply craft, cutters, and other auxiliaries. The best of the lot were the six newly built Wabash-class steam frigates, of 40 guns and 3,300 tons—the Wabash, Colorado, Roanoke, Merrimack, Minnesota, and Niagara. They were the pride of the navy.

During the last weeks before the Virginia secession, the primary concern of the U.S War Department was the Navy Yard at Norfolk. It boasted the largest dry dock on the East Coast and housed the navy’s reserve supply of powder and shot. In addition to the many machine and boiler ships, sail lofts, foundries, and carpenter shops, it also housed nearly 1,200 naval gun barrels, including many of the new Dahlgren type. There were also several warships in various stages of repair, including the nearly new Merrimack, which was undergoing overhaul of her balky engines, and she was considered to be worth more than the rest of the ships in the yard combined.

Accordingly, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles alerted the aging commander of the yard, Commodore McCauly, to rush completion of the repairs to Merrimack and get her ready for sea. He dispatched Commander James Alden to Norfolk to take command of the ship and get her clear as soon as possible. Chief Engineer Benjamin Isherwood was sent along with Alden to oversee the engine repairs. They managed to get the ship operational, but before they could sail McCauly ordered the fires drawn and a further delay, citing his orders to refrain from doing anything that might incite the Virginians to violence.

Chief Engineer Isherwood then returned to Washington to inform Secretary Welles of the situation. Welles was furious. He was now convinced that McCauly had allowed himself to come under the influence of Southerner sympathizers on his staff. Welles then ordered Commodore Hiram Paulding to Norfolk to relieve McCauly.

Destroy the Docks!

Paulding gathered a force of a hundred Marines and took ship in the Pawnee for Norfolk. He stopped off at Fortress Monroe to augment his force with a detachment of Regular Army troops, but by the time they arrived at the Navy Yard it was too late. McCauly had ordered the guns on the Merrimack spiked and the ship scuttled. Mobs were beginning to gather along the fence and at the main gate of the yard. Paulding was now sure he had no course left but to burn and wreck as much as he could and get away in the only three ships that were still in condition to sail. His Marines raced through the yard with sledges trying to destroy cannon and machinery but their efforts were mostly ineffective. One detachment placed charges and powder trains in the dry dock, but it was hastily done and did not destroy the dock.

Finally, Paulding gave the order to torch the last of the ships and buildings, and the Pawnee, followed by the Cumberland under tow of the steam tug Yankee, made her way down the Elizabeth River. It must have broken Paulding’s heart to burn some of the proud old veteran ships, many of which he had served on in younger days. Among them was the Pennsylvania, a huge four-decker of 120 guns, which was at the time the largest warship in the world. As Paulding’s little fleet departed, the Virginians broke through the main gate and busied themselves saving what they could.

When the fires were all out, the damage was found to be surprisingly light. The main magazine with nearly 3,000 barrels of powder was still intact and only a few of the guns had suffered more than superficial damage. U.S. forces were to face the wrong end of many of these cannon later in the war as the Rebels placed them strategically around their most important rivers and harbors.

The Merrimack had lost part of her superstructure and all of her top hamper, but the very act of scuttling had put out the fires in her hull as she settled into the mud. Secretary Welles called it one of the greatest losses of the war, and Congress, as might be expected, launched a full-scale investigation.

If the U.S. Navy was in bad shape when war began, the Confederate Navy was even worse; it was nonexistent. The South had managed to commandeer a few packets, ferrys, and other craft when hostilities were started, but most of their vessels came from purchases abroad. They had no ship yards and practically no manufacturing facilities to make the parts and accessories used to build ships.

Constructing the Iron-Clad Battery

Not so in the North. A crash program was started to build and charter vessels so that within three months of the loss of Norfolk, there was at least one U.S. warship off every Southern port. The rebels knew it would get worse before it got better unless something was done to raise the blockade. C.S.A. Navy Secretary Mallery is credited with the idea of constructing an ironclad battery with which to break the Union siege.

The Merrimack was soon raised in order to salvage her engines, but when Southerners discovered her hull was largely intact, they decided to build upon what was already available and thus save the time otherwise consumed in building a new hull.

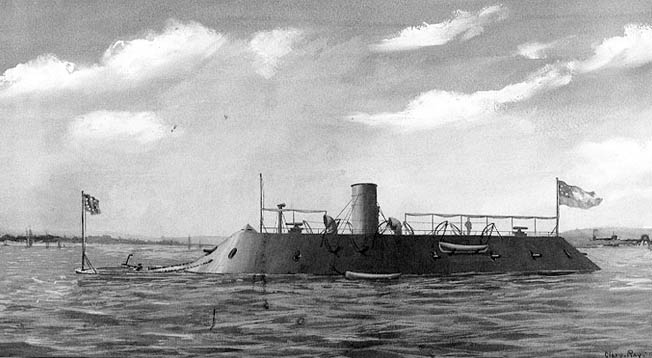

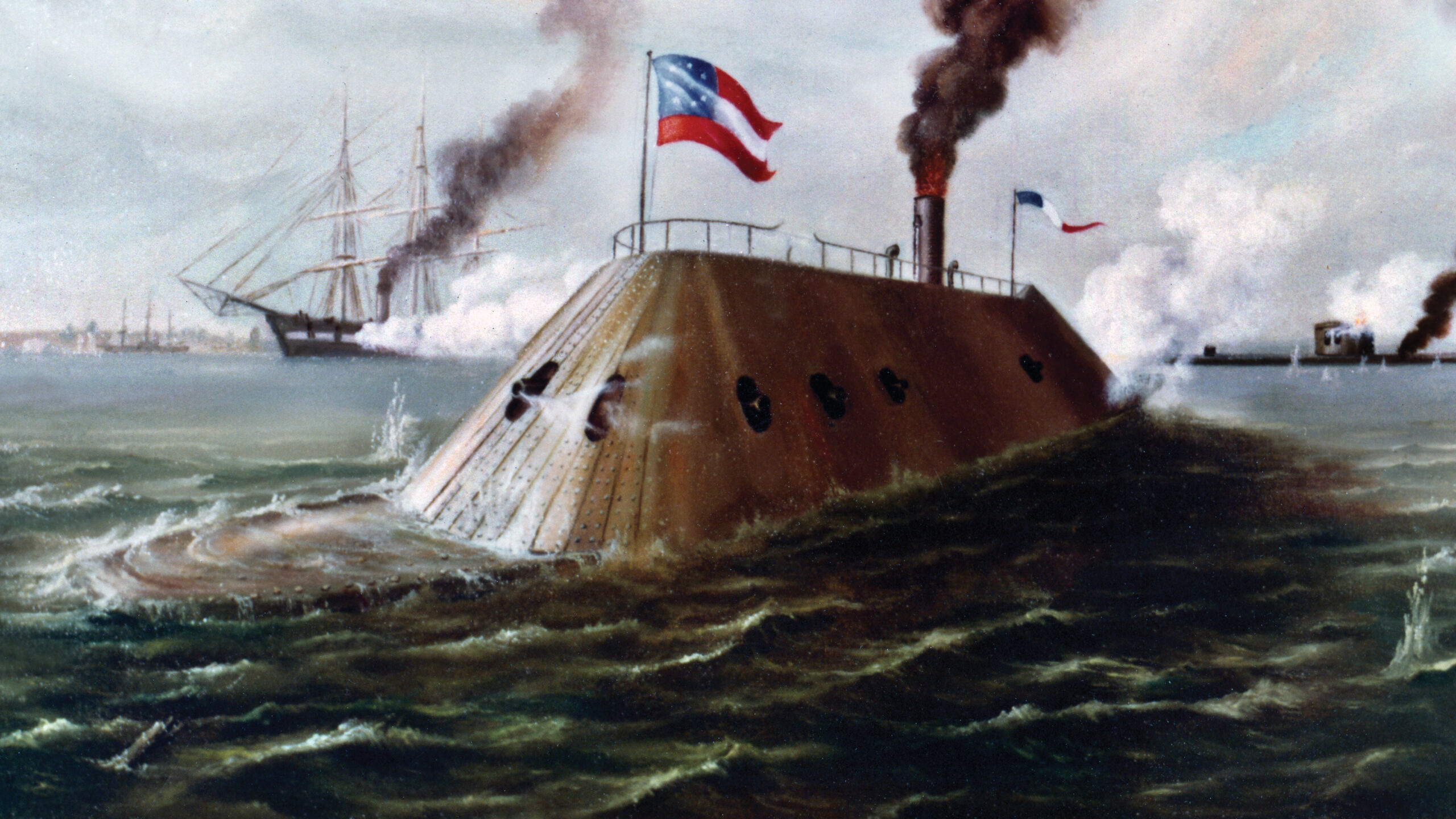

Confederate naval engineers Brooke and Porter did the calculations and drew the plans. They called for a mansard-type framework to be erected on the stripped-down hull. The frame itself would be of 18-inch oak beams that would extend 3 feet into the water at an angle of 35 degrees to protect the wooden hull. Over this would be 20 inches of pine overlaid diagonally with 4 inches of oak plank. The plans called for 4-inch armor-plate on this base, but none was available. Instead, they used railroad iron rolled into 2-by-8-inch bars and bolted diagonally in two layers. There were four gun ports on each side and ports for 10-inch swivel guns fore and aft. The flat roof portion of the mansard superstructure was to have heavy iron grating which would shield the gun deck and provide ventilation. Work was started in July and proceeded as fast as the limited resources of the South would allow.

The Federals soon learned of the work being done on the Merrimack and got their heads together to plan a counter move. They had authorized construction of an ironclad warship some time earlier, but her keel was not yet laid, and her completion was a year away. The files were searched for something that could be built quickly and still trade punches with the Merrimack. They came up with a radical design that had been offered by a somewhat eccentric Swedish-American inventor named John Ericcson. He had been co-inventor of the screw propeller and had many active patents. His specifications claimed the ship could be built in a hundred days and that it would “split the Rebel fleet at Norfolk into matches in half an hour.”

A Radical “Cheese Box on a Raft”

A meeting of the ironclad board was called. Lincoln himself attended, along with his Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Gus Fox. While all agreed that the design was radical and looked like “a cheese box on a raft,” they could not agree on authorizing a trial model. A unanimous vote was required from all three naval officers on the board, and while two were in favor, the third was not—the proposal was turned down. Lincoln was willing to take the advice of his experts even though he was known to be in favor of the design. He is credited with one of his more Lincolnesque quotes as he turned the model over and over in his hands: “All I can say is what the girl said when she put her foot in the stocking. It strikes me there is something in it.”

The board members who were in favor then prevailed upon Ericcson himself to convince the lone dissenting member. They arranged another meeting that the inventor attended, and in a two-hour discourse on hydraulics, dynamics, and the physics of ship stability, the skeptic’s mind was changed and the plan approved.

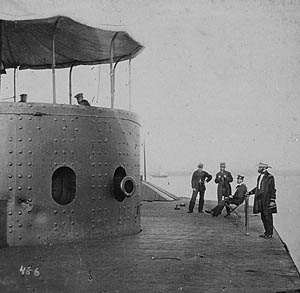

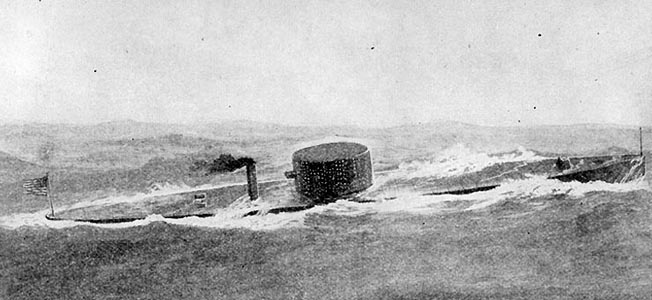

It called for Ericcson to build, in a hundred days, this very unusual vessel for the sum of $275,000. The main hull was to be 125 feet long, 30 feet wide, and 12 feet deep. The raft-like upper deck was to be 170 feet long and 40 feet wide with a 5-foot-deep overhang of thick, wooden blocks sheathed with iron to protect the half-inch iron of the hull. This extra shielding would also serve to protect the propeller and rudder aft and the novel anchor arrangement forward. The only projections above the flat deck of the raft portion, which had a scant freeboard of 18 inches, were to be the stubby pilot house, the 9-by-20-foot diameter gun turret, and the smokestack, which was designed to be removed during action.

Work was started at the Continental Iron Works in Brooklyn, while other area firms received orders for various component parts. Although the Rebels had a two-month head start, it was thought that the better facilities and more abundant manpower in the North would tip the scales.

Christening the Monitor

Secretary Welles suggested that the new vessel be named the Ericcson in honor of its inventor, but Ericcson declined. He proposed instead that it be named Monitor so that the wayward Rebels might be admonished in their folly. He suggested that the British might also take note of the significance of the name because they were known to be building warships for the Confederates.

Work continued on both the Monitor and the Merrimack through the autumn and early winter of 1861. While the idea of iron ships and of wooden ships sheathed in iron was new to U.S. shipbuilders, it was not completely unknown. France had an armored ship of the line, the Gloire, in service and more in production. Britain had the Warrior, a large frigate with protected bulwarks and engine spaces, and more on the ways. They were in a kind of arms race, and though both countries had conducted extensive tests, none of their ships had been in actual combat. The French had used ironclad floating batteries in the Crimean War which they towed into position at Kinburn on the Black Sea. They pounded the Russian forts into piles of rubble as the return fire bounced harmlessly off their protected embrasures.

Ericcson’s one hundred days were up on January 15, 1862 and the Monitor was still not launched. He had designed the ship to take two 15-inch Dahlgren guns, but none was available. He settled for two 11-inch models that were removed from the battleship Dacotah and installed in the 8-inch-thick turret. The Monitor slid down the ways on January 30, 1862, just 115 days from the laying of her keel. Final fitting out and loading took three more weeks, and on February 25, Lieutenant John L. Worden took command of the ship and her 55-man crew, with Lieutenant Samuel D. Greene as his second in command.

Working out the Kinks in the Ironclad

On Monitor’s shake-down cruise, things went so badly that she had to be towed back into New York harbor. Ericcson had to completely redesign her steering gear and her main engine valves. Countless other minor defects cropped up and were corrected as quickly as possible. Her second sea trial went off without a hitch, so Commodore Paulding ordered the little ship to depart for Hampton Roads on March 6.

The Monitor’s voyage started in a snow squall with her in tow of the steam tug Seth Low and under power of her own engines to try to make better time. Paulding had also ordered two small gunboats, the Currituck and the Sachem, to act as escort. Next day Paulding received an order from Secretary Welles to send Monitor up the Potomac to Washington, but by what can only be described as the fortunes of war, the order arrived too late.

Monitor was having problems of her own as she ran into heavy weather on the day of her departure. As the wind and sea rose, she started taking on water where the turret joined the deck. Ericcson had understood that this might happen, since a small clearance had to be allowed for the turret to turn in its machined brass ring. He had provided a small pump to take off the small amounts of water that might be shipped. Unknown to him, shipwrights had pried up the turret and packed the widened slit with oakum. When some of the packing washed out, water poured in faster than it could be pumped out. Fortunately, the storm abated before the ship was in any real trouble.

Next day brought more of the same, only this time the incoming water partially doused fire in one of the boilers and filled the boiler room with steam and gas. To make matters worse, the steering gear jammed and the resultant wild swinging threatened to part the tow hawser. Worden signaled to his tug to slacken speed but could not make himself understood. A distress flare brought one of the escorting gunboats alongside and the message was relayed to the Seth Low. As if on cue, the wind went down and the storm subsided.

March 8 dawned sunny and clear with long swells and light choppy seas. By 5 in the afternoon the little group of ships turned into Chesapeake Bay and headed for Fortress Monroe. From his station atop the turret, Worden saw a huge column of black smoke rising from the direction of Newport News and heard the dull booming of heavy guns.

Iron Twins

By some odd twist of fate, Monitor and Merrimack were launched the same week in January, and were commissioned three weeks later on successive days. The Merrimack was rechristened as the C.S.A. Ironclad Ram Virginia, but she has come down through history as the Merrimac (misspelled, Merrimack being her official name in the Navy list).

Named to command her was Captain Franklin Buchanan, a veteran of over 45 years in the U.S. Navy, whose last post was Commandant of the Washington Navy Yard. When it seemed apparent that his home state of Maryland would secede from the Union, Buchanan had tendered his resignation. Later, Maryland voted to remain in the Union and Buchanan requested his resignation be withdrawn. Secretary Welles refused and Buchanan went South. Appointed as second in command was Lieutenant Catesby ap R. Jones, the very embodiment of a dashing young Southern officer (the “ap” in his name is Welsh for “son of”). Like Buchanan, he had gained his experience in the U.S. Navy and was an ordnance specialist. As such, he had been chosen to oversee the installation of Merrimack’s guns. He was highly qualified. He had been in charge of ordnance installation when Merrimack was fitted out new six years earlier.

Final fitting out and loading of the rebuilt Merrimack was completed on March 7, so Buchanan ordered steam up and lines singled for early-morning departure. He would have preferred a traditional shake-down cruise, but the only area available was filled with enemy ships. Her shake-down would also be her baptism of fire.

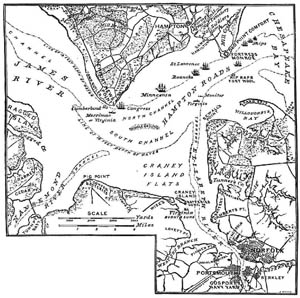

Next morning, March 8, saw more hitches develop, and it was nearly noon before she cast off with many mechanics still aboard. She proved to be awkward and ungainly, her top speed only 6 knots. Her laden draft of 23 feet would restrict her to the deepest parts of the channel and Hampton Roads, but she was well armed and well armored and that was what was important. Just before her departure, her sloping sides had been slushed down with molten tallow in the hope that this would help the shot glance off more easily. At 1 o’clock the Merrimack stopped at Craney Island to disembark the last of the mechanics, and then she made her way out into Hampton Roads.

No one knows for sure who sighted the Merrimack first. The Federal fleet had been under alert for several weeks and had undergone several false alarms. Lookouts on the ramparts of Fortress Monroe sighted her smoke before the vessel herself came into view, and the signal gun had been fired. The crews aboard the Union fleet were lounging on deck and many had their laundry hanging in the lower rigging. Within minutes they had the washing in, the guns run out, the decks dampened and sanded, and ready ammunition at hand. The sailors could not believe what they were seeing. “A barn roof belching smoke” and “that thing” were just some of the remarks. They would have good reason to call it many other things before day’s end.

Changing the Game of Naval Warfare

Buchanan had already noted which ships in the Union fleet were most dangerous and which should be attacked first. The Cumberland, a 24-gun sloop, was smaller than many of the others, but she had been equipped with the new rifled cannon and would be first on his hit list. He had to pass by the 50-gun frigate Congress to get at Cumberland and traded a broadside with her as he swung past. Not a wooden ship afloat could have withstood that pounding from the Congress, but her shot clanged harmlessly off the iron plating of the Merrimack. Buchanan smiled as he saw his own shot raise splinters and smoke on Congress as two of her guns were knocked out.

Buchanan then assigned his two small escorting gunboats, Raleigh and Beaufort, to keep Congress occupied while he continued toward Cumberland. He maneuvered to come in on her forward quarter so that she could not bring her broadside guns to bear, and bored steadily on. His forward swivel gun kept up a steady fire while the forward pivot on the Cumberland replied. As the range closed to 60 yards, Cumberland scored two bull’s-eyes through the Merrimack’s forward casemate causing 19 casualties. Still the Merrimack came on at full speed and rammed Cumberland just aft of her hawse hole. Frames, knees, and deck timbers splintered like laths as the iron spur of the Merrimack pierced the Union sloop. Gunners were knocked to the deck by the force of the blow, but were soon back at the guns again.

As Buchanan backed clear, Merrimack’s iron ram broke off and remained in the side of the Cumberland. This may have kept her afloat a little longer because it partially stopped up the gaping hole in her side. As Merrimack continued to back clear, another shot from Cumberland shattered Merrimack’s anchor shackle, and the heavy chain slashed back into the ship causing seven more casualties. Merrimack’s gunners were not idle either and poured round after round into the dying ship. Cumberland finally settled to the bottom with the tops of her masts still showing and her colors still flying.

Merrimack was now leaking in the bows where the iron ram had broken off; she had 26 casualties, three of her guns were out of action, and she had lost her anchor, but she was still able to fight. Cumberland had caused more damage to Merrimack than she was to endure for the rest of her service, but had died doing it. One of Merrimack’s officers was to write later that, “No ship ever fought more gallantly.” Buchanan brought the Merrimack about and headed for the Congress.

Lieutenant Joe Smith, commanding Congress, watched in horror as the Cumberland sank. He had seen the ramming and was determined not to let it happen to his ship. He slipped his cables and brought the Congress into shoal water, having correctly guessed that the Merrimack drew more water and would not venture too close. At least he would be safe from ramming, and he might even be able to lure the Merrimack into shoal water where she might ground and become a stationary target for the Federal batteries on shore. What Smith did not count on was going aground himself, which is what happened, and now the Congress was a stationary and helpless target.

Buchanan swung around where he could rake Congress from the stern and proceeded to pound her to pieces. One after another, the guns on Congress were silenced as shot and shell rifled her. Smith himself was killed by one blast, and the gun deck was slippery with blood. Command passed to Lieutenant Pendergast, and when the last gun that would bear was knocked out, he could see no reason to continue. He struck the colors and ran up the white flag.

A Controversial Surrender

Firing ceased at once and the Beaufort sent a boat alongside to take off the wounded and prisoners. What happened next was to become one of the most debated and controversial events in naval history. Union rifleman and light artillery on shore either did not see or did not heed the white flag on Congress and opened a sharp fire on the Beaufort and her boats as she was accepting the surrender. Buchanan was flabbergasted.

He recalled the Beaufort at once, and as she was pulling away, fire was seen coming from Congress herself. It seemed almost impossible that there were still people aboard Congress that did not know she had struck. Buchanan had seen enough. He ordered fire resumed with heated shot, and determined to continue until Congress was beyond salvage. He also knew that his own brother was paymaster aboard Congress, but gave no hint of it as he ordered her destruction. Perhaps this ruthlessness drew upon him a Greek-like vengeance: As he mounted the grating to observe the action, he was struck in the hip by a rifle ball fired from shore and had to be carried below.

Command passed to Lieutenant Jones who was just as determined to see the Congress totally destroyed. But by now several fires were seen on the target and Jones was satisfied. He ordered the Merrimack to proceed down channel and engage the next ship in the Union line. This was the Minnesota, onetime sister ship of the Merrimack, who along with the Roanoke, another sister, had followed the example of Congress and moved into shoal water to avoid Merrimack’s ram. Unfortunately, they also ran aground and lay fast in the mud, unable to maneuver. It remained only for Jones to move Merrimack down-channel, where even at the increased range, he could pound them to pieces. His pilots refused.

Command passed to Lieutenant Jones who was just as determined to see the Congress totally destroyed. But by now several fires were seen on the target and Jones was satisfied. He ordered the Merrimack to proceed down channel and engage the next ship in the Union line. This was the Minnesota, onetime sister ship of the Merrimack, who along with the Roanoke, another sister, had followed the example of Congress and moved into shoal water to avoid Merrimack’s ram. Unfortunately, they also ran aground and lay fast in the mud, unable to maneuver. It remained only for Jones to move Merrimack down-channel, where even at the increased range, he could pound them to pieces. His pilots refused.

It was by now 6 o’clock and the light was failing. The tide was going out and the channel depth was decreasing every minute. Jones knew that his pilots were right even though he ached to continue the action. The Merrimack had casualties aboard and was nearly out of ammunition. Three of her guns were out of action. Her stack was so riddled with holes that the engineers had trouble keeping up a draft, and steam pressure was dropping. Her anchor was gone, her bows were leaking badly now, and her crew was exhausted. Jones decided to break and resume action on the following day.

Victory for the Confederates, 400 Casualties for the Union

Merrimack retired under the guns at Craney Island, a good day’s work done. On her maiden voyage she had sunk one Union warship, burned another, and driven two aground. She had caused nearly 400 Union casualties at a cost of 52 for herself and her escorts. The scene of battle continued to be lit by the fires aboard Congress until near midnight, when the flames reached her magazines. She blew up with a spectacular display that seemed to emphasize the completeness of the Confederate victory.

The Monitor and her escorts were just passing Fortress Monroe when the Merrimack called it a day. Darkness was descending when she pulled alongside the Roanoke to report to the squadron commander. Monitor’s crew had hoped for a little rest from their long and stormy voyage but it was not to be. Captain Marston ordered the Monitor to proceed at once to the Minnesota and stand by as several tugs tried to free her from her mud bed. Minnesota had taken some fire from Merrimack’s escorting gunboats, and in returning fire had forced herself further onto the shoal. Captain VanBrunt of Minnesota ordered her lightened, as two tugs and her own engines strained to get her off. It was no use. Finally it was decided to put off further efforts until full flood tide next day. The crews settled in for a few hours of fitful rest.

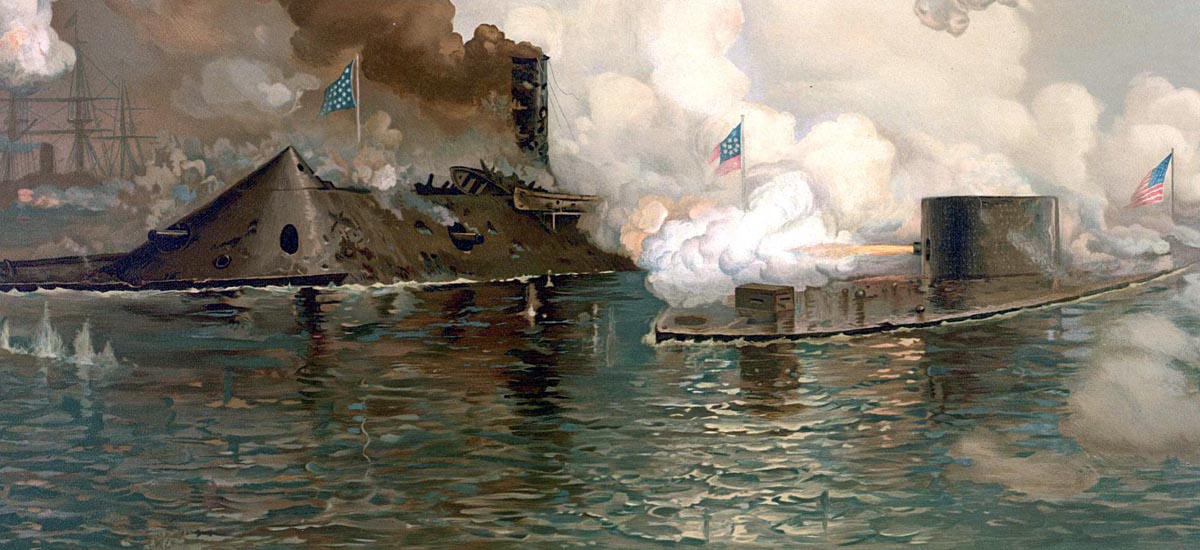

The crew of the Merrimack was up most of the night also. Quick repairs were made to the bow section and ammunition was loaded aboard. Promptly at 6 am, Jones got under-way and headed out into the Roads. As it was not yet fully daylight, Merrimack’s lookouts were puzzled by the strange looking craft tied up alongside Minnesota. At two miles most thought it must be some kind of water tank on a barge which had come to replenish Minnesota’s tanks. Half a mile closer, it became evident that the strange vessel was making smoke and moving out to meet them. At a range of about a mile, all doubts were dispelled as Monitor opened fire with both guns. Merrimack replied at once as the two closed to less than 50 yards. Most of the shot found it’s mark but bounded harmlessly away on both ships.

As the range closed still more, Worden on the Monitor decided to circle his opponent and try to find a vulnerable spot. His was the handier vessel, but he had a slower rate of fire. His speaking tubes were useless in the din of battle, and orders were passed by runner from the pilot house to engine room and turret. Men in both ships were nearly deafened by the clanging of the heavy shot on the iron plates, and learned quickly not to lean against or brace themselves against the armor. Several were injured by the concussion and two gunners in the Monitor’s turret were knocked unconscious.

As the two ironclads circled each other like prizefighters in the ring, the Merrimack came within range of Minnesota’s broadside guns, and Captain VanBrunt blazed away, hoping by sheer weight of iron to breach her casemate. At least 50 shots were seen to strike the ironclad’s side with no apparent effect. Jones in Merrimack now tried to ram the Monitor, but Worden maneuvered aside and took only a glancing blow. It did serve to start another leak in Merrimack’s hull, however, so Jones gave up on that tactic.

The Fated Bout Between Ironclads

After two hours of steady but ineffective firing, the Monitor was forced to retire to shallow water to replenish ready ammunition in her turret. A hatch in the turret floor had to be lined up with a similar hole in the lower deck so that powder and shot could be passed up. VanBrunt on the Minnesota thought he had been abandoned, and though he kept up a steady fire as the Merrimack came closer, he also made provision for destroying his ship.

The Monitor was soon back in action again and found that the Merrimack had grounded in trying to close range on Minnesota. Worden closed on the Confederate ironclad and at one point was actually touching his opponent as he fired both his 11-inch Dahlgrens at point-blank range into her stern casemate. The heavy shot ripped up some of the plating and cracked it in several places. The crew serving Merrimack’s after swivel gun were all knocked to the deck bleeding from their ears and noses from the terrible concussion, but were not seriously hurt. If Worden had been allowed to increase his powder charges, he would probably have penetrated the Merrimack’s gun deck at that range—the Navy strictly forbade the use of more than 15 pounds. Later, gunners discovered that 30 and even 45 pounds could be used with safety.

While the ships were at close quarters, Jones in Merrimack ordered, “Boarders away.” He thought boarders might be able to hammer wedges between Monitor’s turret and the deck. They could drop explosives down the vents, or cover the stubby pilot house with wet canvas. They might even be able to toss grenades through the gun ports. Worden saw his enemy’s intention and backed the Monitor clear before anyone could get aboard.

The Merrimack was still aground and Jones knew that he must get off and maneuver. Chief Engineer Ramsey tied down his safety valves, unhinged the governor and fed pine knots and turpentine to his boilers until they seemed to literally jump up and down. The ship shuddered and shook as the prop churned the muddy water to a froth. Slowly at first, then with a lurch, the heavy Merrimack slid clear. Firing had continued all this time, but as before, without much effect.

Was the Famous Battle an Epic Draw?

Jones decided to try ramming again, but missed. Now Monitor tried to ram Merrimack on the stern in an attempt to disable her rudder or propeller, but she also missed. As she swung past, one of Merrimack’s guns scored a hit on Monitor’s pilot house. The armor was heavy enough here to withstand the shot, but Worden was peering through the five-eighths- inch slot and got his face peppered with cement. He was temporarily blinded and suffered a mild concussion. He ordered the Monitor into shallower water in an attempt to lure Merrimack aground, and turned over command to Lieutenant Greene. Jones in Merrimack did not take the bait, and in fact thought Monitor had quit and was retiring. He swung around for another try at Minnesota.

Once again, Jones’s pilots declined to take Merrimack any closer for fear of grounding, and in a conference with his staff, Jones decided to retire and wait for higher tide before making another attempt. This would give his ship a chance to replenish ammunition, make some more needed repairs, take on coal and water, and rest his crew. At about this time, Greene, now commanding Monitor, decided that the Merrimack could not be lured into shallow water and returned to the channel to find his opponent heading for Sewell’s Point.

Thus ended the Battle of Hampton Roads with each side claiming victory. History has called it a draw.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments