By Jeff Patton, Colonel, USAF (Ret.)

The editorial in the Summer 2013 issue of WWII Quarterly concerned the search for an amphibious DUKW that sank with 25 men aboard on April 30, 1945, in Lake Garda, northern Italy’s largest lake. This follow-up article is by one of the people involved in the search for the vehicle.

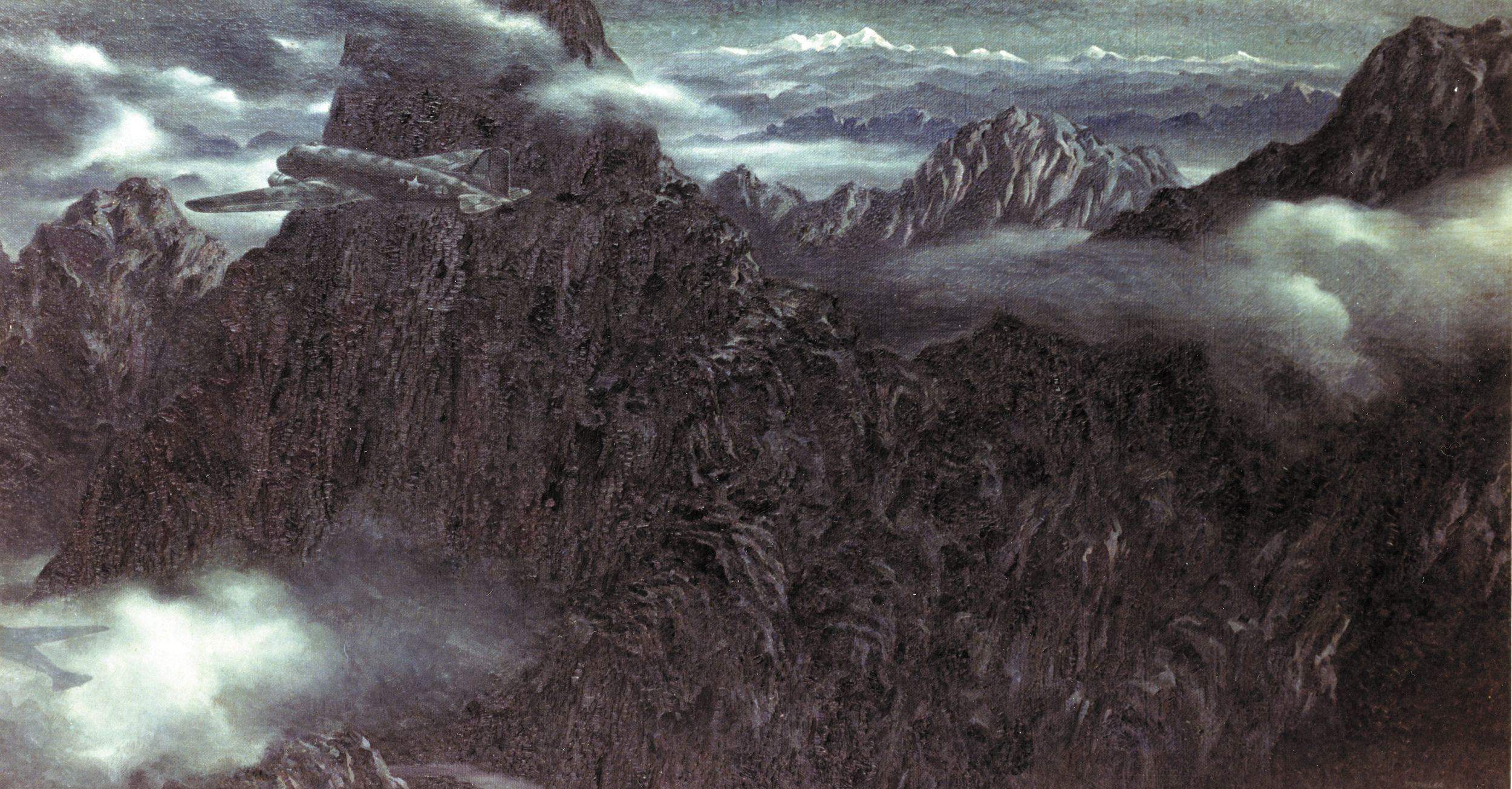

The war in Italy was rapidly drawing to a close. The 10th Mountain Division had succeeded in pushing the retreating remnants of Lt. Gen. von Lemelson’s L Mountain and XVI Panzer Corps north toward the Brenner Pass. In an effort to cut off the retreating elements of these units, the 10th Mountain Division was assigned the task of moving up Lake Garda’s eastern shore.

Despite encountering six blown tunnels, Task Force Darby (under Colonel William O. Darby, the founder of the U.S. Ranger Force and now the 10th’s assistant division commander) led the charge up the lake and liberated the towns of Nago and Torbole on the lake’s northeast corner three days after starting their sweep from the south end.

On the evening of April 30, 1945, three DUKWs carrying members of the 86th Mountain Infantry Regiment departed Torbole for a three-mile trip across the northern end of the lake to arrive at Riva del Garda on the northwest shore to secure the town following its abandonment by retreating German forces.

The DUKWs took a wide swing south from Torbole into the lake to avoid presumed German artillery sited on Monte Brione, which dominates the north end of the lake. During this swing south, one DUKW carrying members of the 605th Field Artillery battalion suffered engine failure. A storm came up on the lake and, with the engine stopped, the vehicle lost steerage and was swamped by waves kicked up by the storm.

According to the sole survivor, Thomas Hough, the men tossed their packs and weapons overboard but the DUKW was overloaded with 25 men plus a 75mm pack howitzer and ammunition and quickly took on water. The vehicle sank rapidly, tossing the men into the icy water. Hough said the rest of the men drowned fairly quickly and he was the only survivor; he was rescued by some soldiers who heard the cries of the men and commandeered a row boat to come to his rescue. The men in the DUKW were nearly the last casualties suffered by the 10th Mountain in Italy, and their bodies were never recovered.

In 2002, 57 years after the event, I was serving on active duty as an Air Force colonel and the Air Attaché to the Republic of Italy in Rome. I was approached at a diplomatic reception being held at the Brazilian Embassy, by an Italian civilian who introduced himself as Giovanni Sulla of Montese. Giovanni told me he was an amateur historian and collector of militaria and had a great interest in the role of the Brazilian and U.S. Armies in the liberation of Italy in World War II. (For the story of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force, see WWII Quarterly, Winter 2013.)

Sulla told me the history of the 10th Mountain’s final days in combat in Italy and specifically told me the story of the loss of the 24 men aboard a DUKW. While it was an interesting story, I wondered why he was telling me, an Air Force officer. He asked, “Isn’t it the policy of the U.S. government to recover its missing in action?” I agreed with him and he proceeded to tell me he thought he knew the approximate location of where the DUKW sank based on an Italian translation of the division’s history.

He ventured that it should be a relatively simple matter to find the DUKW and recover the soldiers’ remains. Little did I realize this “relatively simple matter” would take 10 years and the work of dozens of people to bring to fruition.

I first contacted the U.S. and Italian Navies for help in the search. While supportive of my efforts, they were either not equipped to do the search or had other priorities. Fortuitously, Brett Phaneuff, a member of Submergence Group/PROMARE, contacted me and volunteered to find the DUKW. PROMARE is an organization that specializes in deep-water salvage and exploration and was ideally suited to conduct a search.

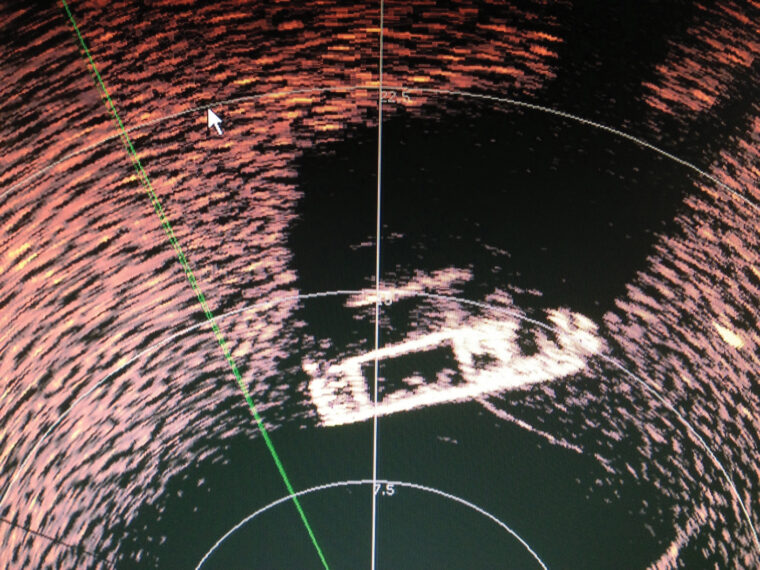

Over the next two years, we conducted several surveys of the bottom of the northern end of the lake with towed side-scan sonar and a Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) with photographic capability. We imaged numerous items that appeared to be the DUKW on sonar but when investigated with the ROV, they turned out to be sunken vehicles or large rocks that had fallen into the lake. We saw no trace of the DUKW or the missing soldiers.

PROMARE got involved with another project and the search was suspended in 2004. In December 2012, I was shocked to hear that the DUKW had been found!

A group of Italian volunteers who work for the Volontari del Garda (literally, Volunteers of Garda) had been searching on weekends in the lake for almost a year using sonar and an ROV and found the DUKW sitting upright in 900 feet of water approximately one mile farther south than we had searched in 2003 and 2004.

The Volontari are like an EMS service that searches for people and cars and boats lost in the lake, so they have the proper equipment and training to conduct a search. The Volontari had taken more than 3,000 sonar scans, crisscrossing the lake bed until late at night on December 12, 2012, when lowering the sonar for the last time that night, they almost landed the sonar directly on top of the DUKW, missing it by a few feet! Immediately, the ROV was sent down to identify the vehicle.

Two DUKWs were reported lost in 10th Mountain history. One was sunk by tank fire close to the east coast of the lake, and the other was the DUKW carrying the 24 men from the 605th FA. This latter DUKW was undamaged and was obviously the correct one. Hough said the engine had quit and this DUKW’s engine compartment cover was open, evidence that the men were trying to get the engine restarted prior to sinking. Photos showed little corrosion from the 68 years it had been submerged and sitting on a muddy bottom.

I was graciously invited to participate in the search for the remains of the soldiers by the Volontari during the first three weekends in March 2013 and I eagerly accepted. I accompanied them aboard their 12-meter vessel, Volga 2026, for five 9-10 hour days searching in the vicinity of the DUKW for our missing soldiers.

I cannot say enough about the passion and dedication of these men in pursuing the location of our fallen. They developed a daily search plan then used the sonar to search the area. I never heard one word of discouragement despite the hundreds of concrete blocks and other false targets we encountered. Their efforts to find these men who all they knew about where they died to liberate Italy were heartwarming to this American.

Unfortunately, we were unable to find the soldiers. The most likely scenario is that the remains of the soldiers have been entombed in the lake bottom by the current and are not recoverable. The Volontari have received permission from provincial authorities to make an attempt, probably in the spring of 2014, to raise the vehicle and conduct a more thorough survey surrounding the DUKW for artifacts and human remains.

We can draw this chapter of the long and glorious history of the 10th Mountain Division to a close. Our men are in eternal rest in a place known only to God, surrounded by their comrades and embraced by the country they died to liberate. May they rest in peace.

Postscript: On April 25, 2013, in commemoration of Liberation Day in Italy, two restored, privately owned DUKWs with re-enactors dressed in World War II U.S. Army uniforms laid a wreath in Lake Garda above the site of sinking of the DUKW in honor of the 24 young American soldiers who rest below. As the wreath was laid, a bugler played “il Silenzio,” a beautiful tribute similar to “Taps.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments