By Christopher Miskimon

Griefswald, a small German city on the Baltic Coast, lay directly in the path of Soviet tanks on April 30, 1945. Fear ran throughout the town as Germans worried what the approaching Russians might do to them in return for what the Third Reich inflicted on the Soviet Union in years past. A resident German commander, Colonel Rudolf Hagen, took matters into his own hands. He gathered a group of local officials and began negotiating for Greifswald’s surrender.

The meeting took place at 3 am. Eight hours later, the first Russian tanks entered the city. Soviet officers accepted the German capitulation and occupied the town. It was all completed very quickly, and order was maintained. The next day the rector of the local university noted in his diary that there were isolated reports of looting and rape. The Germans again met with the Soviet commander, and they agreed to post police throughout the town to maintain peace and order. Griefswald’s people had avoided not only the destruction of their home but also the rampant violation of their very persons.

The town of Demmin, a few miles southwest, suffered a far worse fate. A Soviet armored formation approached it on April 30. Town leaders hoisted a white flag on the church tower. The Russian commander, eager to avoid a pitched battle for the town, exhorted his men to maintain their discipline and refrain from abusing the local civilians. A trio of soldiers was sent to negotiate the town’s surrender, armed with a promise to spare the townspeople from looting and theft if they gave up peacefully. Hopes on both sides were tragically dashed by a detachment of SS troops, who ambushed the negotiators, killing all three. They then proceeded to retreat through the town, destroying bridges as they went. This may have slowed the avenging Soviet columns, but it also trapped the German civilians. The citizens raised more white flags as the Russians entered Demmin, but fanatic Hitler Youth opened fire on them. Enraged, the Russian troops set the town ablaze.

Panic gripped the people within the town. Many began committing suicide, terrified beyond reason of what the Russians would now do to them. Entire families perished this way. For their part, some Soviet soldiers inflicted a spree of rape on the female inhabitants. Others, horrified at what their comrades were doing, tried to stop the waves of suicides and brutality occurring amid the flames. By the next day more than 900 Germans were dead and the dreaded Soviet NKVD field police had to be brought in to quell the chaos.

April 30 also marked Adolf Hitler’s death by suicide. Simultaneously, his Third Reich was also in its death throes. Germany was besieged from east and west by the triumphant Allied armies; another nation would have long since relented. The Nazis had such a hold over their populace as to make them continue fighting long after any hope of ending the struggle short of full defeat was over. It was a period of swirling bedlam as Allied troops tried to end the war, racing toward agreed upon lines that delineated future sectors of control.

April 30 also marked Adolf Hitler’s death by suicide. Simultaneously, his Third Reich was also in its death throes. Germany was besieged from east and west by the triumphant Allied armies; another nation would have long since relented. The Nazis had such a hold over their populace as to make them continue fighting long after any hope of ending the struggle short of full defeat was over. It was a period of swirling bedlam as Allied troops tried to end the war, racing toward agreed upon lines that delineated future sectors of control.

Axis troops tried desperately to hold off the advancing Soviets to allow more of their soldiers and civilians to reach the Americans and British, where it was assumed they would be safe from revenge. This confused period is laid out in After Hitler: The Last Ten Days of World War II in Europe (Michael Jones, NAL Caliber, New York, 2015, 374 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $27.95, hardcover).

At the battlefield level individual soldiers and civilians struggled to stay alive in the churning turmoil of the final destruction of Nazi Germany. There was truly no point in further bloodshed, but the troops still received orders and were still moved across the map with little choice but to continue. Civilians had to deal with starvation, the depredations of the enemy, and even the callousness of their own soldiers. At the higher levels, generals, heads of state, and politicians strived to end the war on terms favorable to their respective peoples and in a way that negated the already growing cracks in the alliance, cracks the surviving Axis leadership tried to exploit. In the end these efforts were successful due to the work of myriad players from Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower down to junior officers given missions in the field on short notice.

The author does an excellent job relating the numerous facets of the war’s final days. The reader gains a solid understanding of how people great and small wove together the events that ended history’s greatest conflict in Europe. The writing is clear and compelling, full of vignettes highlighting the experiences of the participants. His analysis of decision making and actions is thoughtful and possessed of insight. The book sheds light on a dark time, putting the reader amid the battlefield smoke and closed-door meetings that culminated in the war’s end.

Hump Pilot: Defying Death Flying the Himalayas During World War II (Nedda R. Thomas, History Publishing Company, Palisades, NY, 2015, 192pp., photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $18.95, softcover)

Hump Pilot: Defying Death Flying the Himalayas During World War II (Nedda R. Thomas, History Publishing Company, Palisades, NY, 2015, 192pp., photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $18.95, softcover)

Flying the Hump was among the most dangerous air transport missions a pilot could perform during World War II. This was all the more poignant because the danger posed by the enemy was relatively low. No antiaircraft guns waited among the peaks and valleys of the Himalaya Mountains. Encounters with Japanese fighters were rare. The true dangers were posed by the environment. Weather could change quickly, and the harsh terrain virtually precluded a survivable crash landing. An engine failure was likewise an almost certain death sentence. Even when a crew survived a crash landing, the freezing cold and winds would soon finish them. The route over these mountains was known as the “Aluminum Trail,” so named due to the 700 crashed aircraft that littered the ground, often serving as grave markers for the crews.

Ned Thomas was one of the American pilots who flew the Hump. His experiences are ably recorded here, providing an in-depth, fascinating look at a job that was supremely dangerous even without the specter of combat. The book includes enough practical detail about flying to inform the reader without becoming a technical manual. The descriptions of missions over the Hump are vivid and engaging, adding a human face to the drama created by perilous missions over a vast mountainous wasteland. The story of Ned Thomas and his fellow pilots exemplified courage in a perhaps unique way that deserves attention and is well worth reading.

Angels of the Underground: The American Women Who Resisted the Japanese in the Philippines in World War II (Theresa Kaminski, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2015, 512pp., photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $27.95, hardcover)

Angels of the Underground: The American Women Who Resisted the Japanese in the Philippines in World War II (Theresa Kaminski, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2015, 512pp., photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $27.95, hardcover)

When the Philippines fell to Imperial Japan in 1942, the surviving American soldiers mostly went into captivity. A few managed to hide in the jungle and either make their escape or join the resistance. For the American civilians still on the islands, there was little choice but to live under the Japanese. A few joined the resistance, some serving secretly under the noses of the occupiers. Four American women—Claire Phillips, Peggy Utinsky, Gladys Savary, and Yay Panlilio—and a Filipino-American did just that, living in Manila. From there they gathered information and passed it to the guerrillas hiding in the hills around the city. They obtained supplies for the resistance fighters and even joined them. Several of them were the wives of American servicemen lost in the fighting. Their husbands’ comrades were now prisoners in Cabanatuan and Camp O’Donnell. At even greater risk they smuggled food and medicine into the camps, helping the men endure the extreme privations inflicted upon them.

This book weaves the story of these four heroic women into the greater narrative of the Philippine occupation. Their personal ordeals are told in clear, dramatic prose, highlighting both their suffering and bravery under harsh circumstances. The experiences of these four heroines shed light on the ways women contributed to eventual victory and the price they often paid for it when they were caught up in the actual war zones.

Operation Long Jump: Stalin, Roosevelt, Chur-chill, and the Greatest Assassination Plot in History (Bill Yenne, Regnery History, Washington, D.C., 2015, 244pp., photo-graphs, bibliography, index, $29.99, hardcover)

Operation Long Jump: Stalin, Roosevelt, Chur-chill, and the Greatest Assassination Plot in History (Bill Yenne, Regnery History, Washington, D.C., 2015, 244pp., photo-graphs, bibliography, index, $29.99, hardcover)

When Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill went to Tehran, Iran, for a meeting on the conduct of the war, little did they know the Third Reich had set into motion a scheme to kill them. Both the American and British leaders wanted to meet elsewhere, but Stalin, paranoid over going too far away from the Soviet Union and afraid to fly, insisted. Hitler approved a plan to kill the three men; even the famous German commando Otto Skorzeny became involved. In the end the plot failed, but only after a twisting trail of strange events combined with what the author describes as “amateurish bungling straight out of the Keystone Cops.”

The author did extensive research to uncover what facts remain of this far-fetched and improbable assassination attempt. Much of the story was buried under wartime secrecy needs and lost thereafter. As is often the case with espionage incidents, the details were scattered among numerous sources and persons, just a piece of the puzzle here and there. The writer does a good job pulling together these disparate bits of evidence and combining them into an enjoyable, well-crafted account.

Cushing’s Coup: The True Story of How Lt. Col. James Cushing and his Filipino Guerrillas Captured Japan’s Plan Z and Changed the Course of the Pacific War (Dirk Jan Barreveld, Casemate Publishing, Havertown, PA, 2015, 304pp., maps, photographs, notes bibliography, $32.95, hardcover)

Cushing’s Coup: The True Story of How Lt. Col. James Cushing and his Filipino Guerrillas Captured Japan’s Plan Z and Changed the Course of the Pacific War (Dirk Jan Barreveld, Casemate Publishing, Havertown, PA, 2015, 304pp., maps, photographs, notes bibliography, $32.95, hardcover)

When the Japanese landed in the Philippines, Lt. Col. James Cushing was working as a mining engineer on the island of Cebu. Rather than surrender to an uncertain fate, he took command of the local guerrilla group that prosecuted its own war against the invaders. In 1944, luck placed opportunity in Cushing’s hands. A typhoon downed a Japanese plane carrying an admiral and war plans; both washed up on the shores of Cebu. Cushing and his soldiers captured them, and thus began a deadly chase as the Japanese searched the island for their lost officer. Meanwhile, Cushing tried desperately to get word of his prize to the Allies.

This book is full of detail not only about the capture of the admiral and the war plans, but also of the hard service of Filipino resistance fighters and the war they fought. It captures the difficulties faced by Cushing and his troops as they seized the opportunity given them, revealing the compelling story of how a few unknown fighters had a major impact on the war’s outcome.

The Siege of Brest 1941: The Red Army’s Stand Against the German During Operation Barbarossa (Rostislav Aliev, translated by Stuart Britton, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2015, 215pp., maps, photographs, $19.95, softcover)

The Siege of Brest 1941: The Red Army’s Stand Against the German During Operation Barbarossa (Rostislav Aliev, translated by Stuart Britton, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2015, 215pp., maps, photographs, $19.95, softcover)

When the Nazi juggernaut rolled over the Soviet border in June 1941, it advanced rapidly, leaving thousands of Soviet troops and civilians behind the lines. The city of Brest, near the Polish border, was quickly overwhelmed by the Germans. Then, in 1942, the Soviets captured a German document, an account of the taking of the city by the German 45th Infantry Division. To their surprise, the Russian leaders discovered the Red Army had held out in Brest for over a week, fighting from bunkers and tunnels within the city. The heroic story was altered for propaganda purposes and published as an example of Soviet courage and tenacity.

The stories of the soldiers who served there is combined with the surviving battle reports to tell the story of this little known fight. The author weaves together both German and Russian interpretations to give a detailed account of what occurred in Brest in a vivid blow-by-blow style.

Forgotten Sacrifice: The Arctic Convoys of World War II (Michael G. Walling, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2015, 284pp., maps, photo-graphs, bibliography, index, $$14.95, softcover)

Forgotten Sacrifice: The Arctic Convoys of World War II (Michael G. Walling, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2015, 284pp., maps, photo-graphs, bibliography, index, $$14.95, softcover)

The Murmansk Run was the route Allied convoys took from the West to the far northern city of Murmansk to deliver supplies the Soviet Union needed to stay in the war. As the convoys carried their cargoes north, the Germans threw ships, submarines, and aircraft at them. The crews of sunken or stricken ships might survive only to battle another enemy—the cold waters of the North Atlantic. Despite the risks, the sailors of both warships and merchantmen kept going, braving both bombs and ice to do their duty.

Full of oral histories from veterans as well as original research in the Russian Naval Archives, the author effectively tells the story of the sailors who dared fight both man and nature. There is a useful “briefing” chapter, which is essentially a primer on how the convoy war was fought, giving the reader excellent detail on the many facets of the fighting.

“Careerists”: Quarry Duty in the Soviet Army (Ilmars Salt, translated by Gunna Dickson, Author House, Bloomington, IN, 2015, photographs, $18.49, softcover)

“Careerists”: Quarry Duty in the Soviet Army (Ilmars Salt, translated by Gunna Dickson, Author House, Bloomington, IN, 2015, photographs, $18.49, softcover)

While most books on the history of the war focus on the fighting, this one looks at some of the civilians who suffered dreadfully in Siberia toiling for the war effort. The author was just a boy when the Soviet Union took over Latvia in early 1941. His land-owning family lost its home and was deported to Siberia to work in a quarry. There, the family members grimly joked they were “careerists,” a play on the similarity between the Latvian words for “career” and “quarry.” Both of Ilmars’ parents and his grandmother died during the war; only the orphaned children returned home in 1946. To add insult to injury, the author later found himself conscripted into the Soviet Army. Happily, after the fall of the Soviet Union Ilmars was able to reclaim his family’s lost land. Overall, the book is a serious look at the Soviet camp system during World War II and those who suffered through it.

P-51 Mustang: Seventy-Five Years of America’s Most Famous Warbird (Cory Graff, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, 2015, 256pp., photographs, index, $48.00, hardcover)

P-51 Mustang: Seventy-Five Years of America’s Most Famous Warbird (Cory Graff, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, 2015, 256pp., photographs, index, $48.00, hardcover)

The Mustang is arguably the most famous of all American fighter aircraft. It was the plane that took control of the skies away from the Luftwaffe and escorted thousands of bombers to their targets in Germany. In the Far East, they flew over the Pacific Ocean, India, and China. Along the way they gained a reputation as a war-winning aircraft second to none. They could perform ground attacks or air-to-air combat equally well; Mustang pilots often had kill symbols affixed to their fuselages symbolizing enemy planes, locomotives, and vehicles.

Zenith Books specializes in these sorts of large, coffee table-style books and they do not disappoint here. The work is lavishly illustrated with period photographs, advertisements from contemporary publications, and images of the P-51 from model kits to vintage comic book covers. Mustangs are shown everywhere from the factory to the maintenance shop to the battlefield. Detailed text accompanies the illustrations, focusing not only on the plane’s service but its legacy, including surviving Mustangs today.

New and Noteworthy

Rising Sun, Falling Skies: The Disastrous Java Sea Campaign of World War II (Jeffrey R. Cox, Osprey Publishing, 2015, $14.95, softcover) A new paperback edition covering the often overlooked naval battles of the Pacific War’s first sea campaign.

Rising Sun, Falling Skies: The Disastrous Java Sea Campaign of World War II (Jeffrey R. Cox, Osprey Publishing, 2015, $14.95, softcover) A new paperback edition covering the often overlooked naval battles of the Pacific War’s first sea campaign.

Torch: North Africa and the Allied Path to Victory (Vincent P. O’Hara, Naval Institute Press, 2015, $49.95, hardcover) A new look at the first Anglo-American counteroffensive of the war. It opened a new front against the Nazis and gave American troops much needed experience.

How to Become a Spy: The World War II SOE Training Manual (The British SOE, Skyhorse Publishing, 2015, $16.99, softcover) A reprinted edition of the British manual of “ungentlemanly warfare” and covert operations. Includes original cipher diagrams and tips on disarming sentries.

Hit the Target: Eight Men Who led the Eighth Air Force to Victory over the Luftwaffe (Bill Yenne, NAL Caliber, 2015, $26.95, hardcover) Tells the story of the unit through eight of its members, both officers and enlisted men. They fought a years-long struggle aimed at bringing the German homeland to its knees.

Ghost Patrol: A History of the Long-Range Desert Group 1940-1945 (John Sadler, Casemate Publishing, 2015, $32.95, hardcover) The story of one of Great Britain’s most famous special forces units. It undertook extended reconnaissance missions and raids under the most extreme conditions.

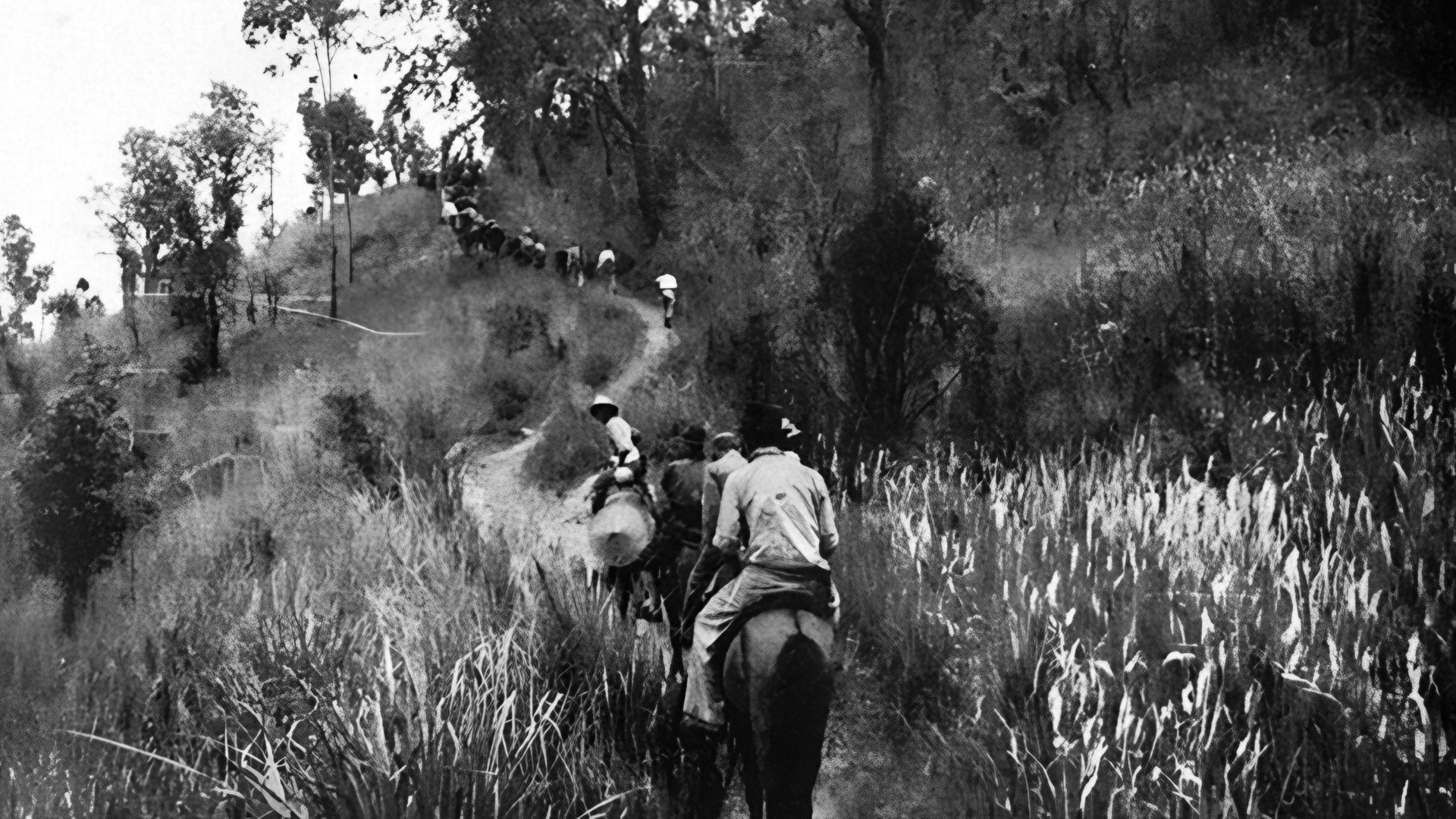

Burma Road: Stilwell’s Assault on Myitkina (Jon Diamond, Osprey Publishing, 2015, $21.95, softcover) This offensive was aimed at retaking northern Burma from the Japanese. Doing so would reopen the land route to China and help keep Allied troops supplied and in the war.

The Oxford Illustrated History of World War II (Edited by Richard Overy, Oxford University Press, 2015, $45.00, hardcover) A thorough summary of the war covering wide-ranging topics such as production, economics, innovations, and events on the battlefields. Well illustrated with many rarely seen images.

The Oxford Illustrated History of World War II (Edited by Richard Overy, Oxford University Press, 2015, $45.00, hardcover) A thorough summary of the war covering wide-ranging topics such as production, economics, innovations, and events on the battlefields. Well illustrated with many rarely seen images.

Bombing Europe: The Illustrated Exploits of the Fifteenth Air Force (Kevin A. Mahoney, Zenith Press, 2015, $35.00, hardcover) This unit was assigned to take the fight to the Nazis in southern Germany, Austria, the Balkans, and Eastern Europe. It braved both enemy fighters and antiaircraft guns to bomb its targets.

German U-Boat Ace Rolf Mutzelburg: The Patrols of U-203 in World War II (Luc Braeuer, Schiffer Publishing, 2015, $29.99, hardcover) One of the top U-boat aces of the war, Mutzelburg prowled the shores of Canada. The author used the photos of former crew members and the submarine’s original logbooks.

The Orpheus Clock: The Search for My Family’s Art Treasures Stolen by the Nazis (Simon Goodman, Scribner, 2015, $28.00, hardcover) The author’s parents died in the concentration camps after losing everything else to Nazi predations. They owned a world-class art collection that Goodman spent two decades trying to recover from collectors, thieves, and even governments.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments