By Blaine Taylor

On August 4, 1790, at the urging of Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, the United States Congress authorized the construction of 10 armed revenue cutters. These cutters, to be captained by tough, experienced “war hawks,” would have the primary mission of enforcing the fledgling nation’s new protective tariff and cutting down on the endemic smuggling that had been almost a patriotic duty during the original 13 colonies’ long subjugation by Great Britain. Faced with an eighty-million-dollar debt, the United States could not afford to keep losing such much-needed revenues. Hamilton and his new Revenue-Marine Service would remedy that.

Establishing the Coast Guard

The first 10 cutters of the Revenue-Marine Service were stationed in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Long Island Sound, New York Harbor, Delaware Bay, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and the Chesapeake Bay. Two-masted schooners, 50 feet long, the cutters were of the type known as Baltimore Clippers. Quick to come about and sharp to windward, the cutters were swift enough to catch much larger ships and shallow enough to sail into waters where deeper-hulled vessels could not go. By 1796, thanks in large part to the cutters, the nation’s entire foreign debt had been paid off.

As the country grew, more cutters joined the fleet in time to fight in the first war of the new nation—the quasi-war with Republican France. Despite being allies in the Revolutionary War, the United States and France increasingly had grown apart, and France had begun seizing American vessels bound for England. In 1796, Congress authorized the president to order the revenue cutters to defend the coast and protect American shipping from French threats. At the same time, a new Navy Department was set up to direct the conflict, and the Revenue-Marine was placed under Navy control during times of war. (It would remain under the Treasury Department during times of peace.) A distinctive new flag was prepared, consisting of 16 perpendicular stripes, alternately red and white, and a dark-blue ensign on a white field. Fourteen new cutters were turned out between 1798 and 1801, and eight other smaller ships were built or purchased, including a captured French schooner. In February 1801, a new treaty with France ended the quasi war, and the Revenue-Marine returned to Treasury service.

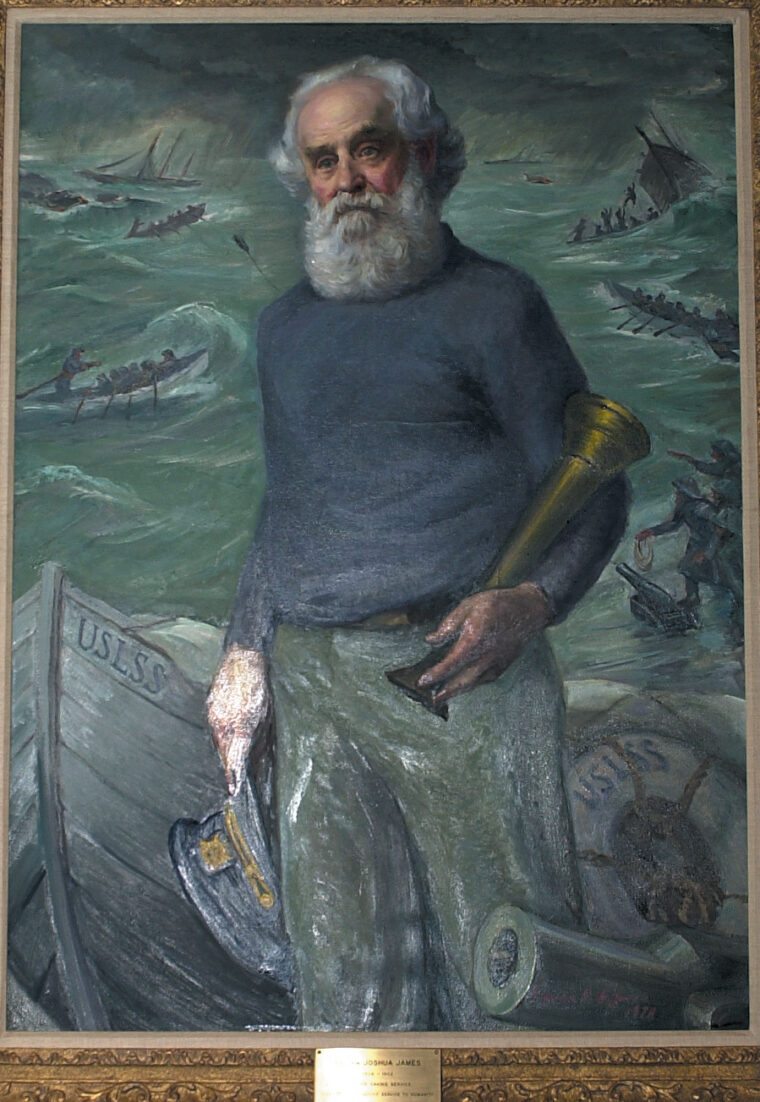

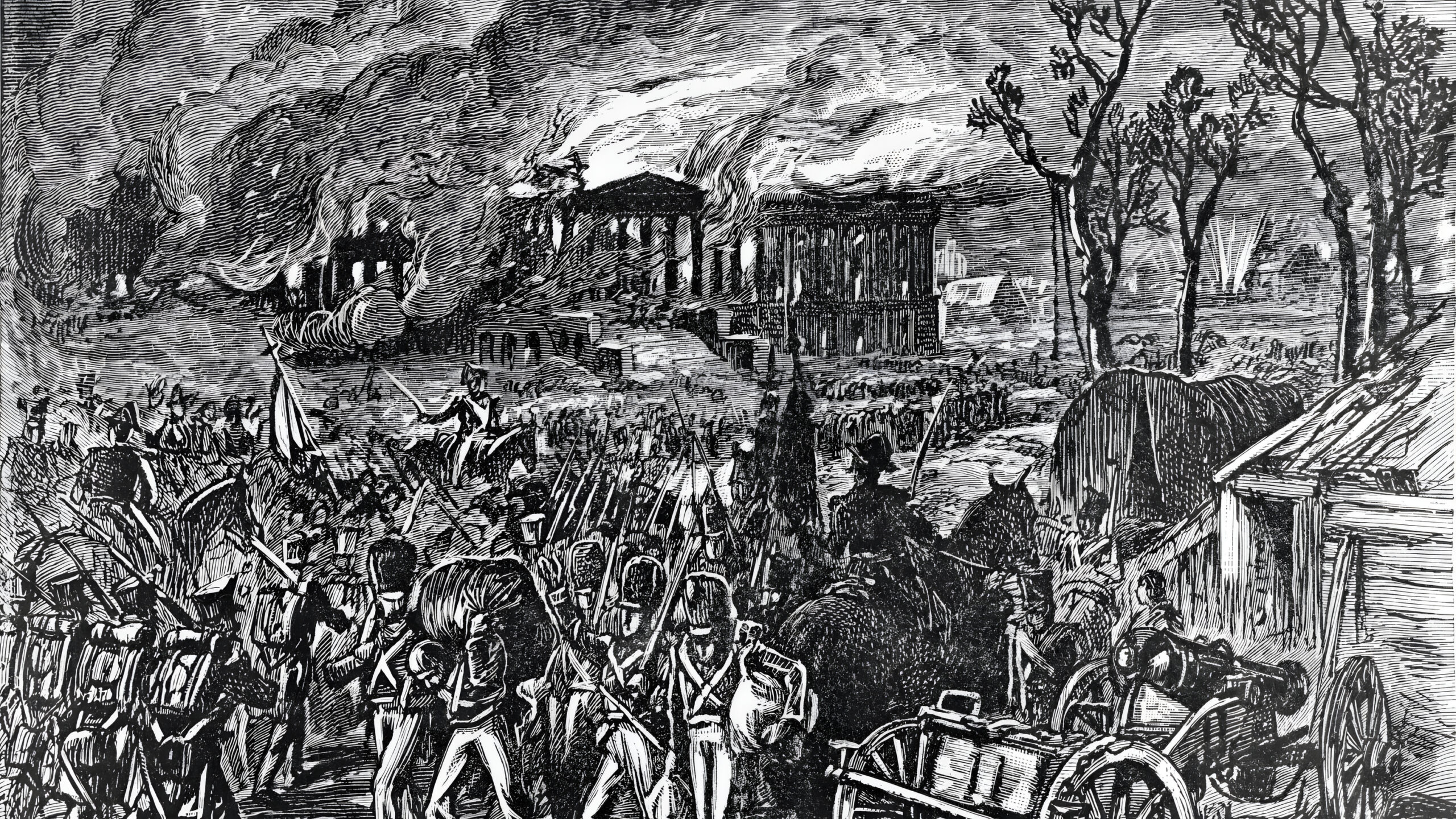

Throughout the nineteenth century, the revenue cutters fought successively in the War of 1812, the Barbary Coast War, the Seminole War, the Mexican War, the Civil War, and the Spanish-American War. Besides its wartime duties, the Revenue-Marine Service undertook new activities in the bustling 1800s, including the prevention of alien-smuggling and exploration of the newly acquired Alaskan territory. At the same time, the Bureau of Navigation and Steamship Inspection Service and the Life Saving Service were formed.

Becoming the Modern Coast Guard

In 1915 the Life Saving Service joined with the Revenue Cutter Service to form the United States Coast Guard. Subsequently, some 8,835 members of the Coast Guard saw action in World War I, and 201 lost their lives—the highest fatality rate of all the American armed services. A bill to make the Coast Guard a permanent member of the Navy was defeated, and the Coast Guard was returned to the Treasury Department in 1919.

After passage of the Volstead Act in 1920, the Coast Guard became active in combating liquor smuggling on the seacoasts and on the Great Lakes, the Rio Grande and the St. Lawrence River. It was a return to the Guard’s original mission, but the nation’s literal thirst for whiskey made the duty both perilous and unpopular. On shore, guardsmen were routinely cursed as “sneaks and snoops,” and at sea they were in ever-present danger of being shot. One of the most sensational episodes came in 1927, when three Coast Guardsmembers were shot and killed off the Florida coast between Miami and the island of Bimini. The perpetrator, a well-known smuggler named James Horace “Red” Alderman, was hanged in the Coast Guard hangar at Fort Lauderdale a few months later.

The repeal of prohibition in 1933 was met with much relief by Coast Guard members, who had been forced to carry on the service’s other duties—including enforcing Alaskan game laws, patrolling the North Pacific halibut trade, and backing up anti-pollution measures in American harbors and navigable waters—short-handed. In 1939, the Coast Guard took on another duty when the Lighthouse Service became part of the Coast Guard. And in 1942, the Bureau of Navigation and Steamship Inspection became absorbed into the Coast Guard as well.

World War II found the Coast Guard combating German U-boats in the waters off the east coast, from Maine to Florida, and Japanese submarines on the Pacific coast from the Aleutians to the Pacific. At the same time, the Coast Guard was tasked with providing port security for more than 40 ports, including inland ports such as Detroit, St. Louis, Cleveland, Chicago, and Duluth, and harbors in Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. In addition, the Coast Guard had to protect waterfront oil and utility installations, ship-loading facilities, and beaches. Coast Guard vessels took part in the Allied landings at North Africa, D-Day, and the Italian campaign, as well as the Navy’s island-hopping campaign in the Pacific.

By the end of World War II, the Coast Guard had become a truly multi-mission service. On the Great Lakes and the rivers of the United States, the service broke ice, marked channels, and helped with flooded areas. Ocean patrols became a major mission from 1940-76, as the Coast Guard helped ships and planes in their navigation, as well as providing weather information that was vital for coastal regions.

During the 1970s, a series of oil tanker disasters expanded the Coast Guard’s marine safety mission, and oil pollution strike forces were created within the service to fight such spills. In the 1980s, several dramatic cases emphasized the service’s strict professionalism. During the Cuban boatlift in the early eighties, over 225,000 Cubans were assisted by the Coast Guard in their attempts to reach the U.S mainland. In addition, Coast Guard and Canadian helicopter pilots helped save over 500 passengers from the cruise ship Prisendam without any injuries or loss of life.

Protecting ports and waterways and breaking ice continue to be Coast Guard missions. Search and rescue remains a constant duty, with the service handling over 70,000 calls each year and saving an average of 5,000 lives annually. At the same time, the Coast Guard maintains its defense readiness capabilities—a task that gained paramount importance after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001—as part of the Department of Homeland Security. (One of the major points the Coast Guard protects is the Potomac River’s waterway approaches to the nation’s capital, Washington, D.C.).

The United States Coast Guard Academy

The United States Coast Guard Academy, established in 1877, is located on the west bank of the Thames River in New London, Conn. Its red-brick, white-trimmed Georgian colonial buildings are the home to the Coast Guard’s Corps of Cadets, the Leadership Development Center, the 295-foot training ship Eagle, the Coast Guard Band, and the Coast Guard Museum. The smallest of the nation’s service academies, the Coast Guard Academy is also unique in that it accepts cadets without recourse to political appointments or geographical considerations, basing admittance on nationwide aptitude tests.

Each July, more than 250 young men and women arrive at the Academy to begin the intense indoctrination program known as “Swab Summer.” During the next four years, the cadets’ undergraduate education, as well as their professional and military development, are supported and enhanced in an environment that stimulates a high sense of integrity, commitment, respect, discipline, and camaraderie. Following graduation and the receipt of a bachelor of science degree, the newly commissioned ensigns begin their five-year service obligation with a tour of duty aboard a Coast Guard cutter.

In 1998, the Coast Guard Academy added the Leadership Development Center (LDC), creating an educational center of excellence for the entire Coast Guard—military and civilian, officers and enlisted. It supports individual, unit, and organizational training to ensure that graduates are well prepared to lead and carry out the Coast Guard’s multiple missions. By building teamwork and individual leadership skills and emphasizing commitment to lifelong learning and professional development, the Academy is the wellspring of the service’s leadership and character development. The LDC consolidates into a single, rich learning environment, prominent schools from around the country, including Officer Candidate School, Chief Warrant Officer Indoctrination School, Chief Petty Officer Academy, Command and Operations School, Officer in Charge School, Key Civilian Orientation Program, and the Leadership and Quality Institute.

A Visit to the Coast Guard Museum

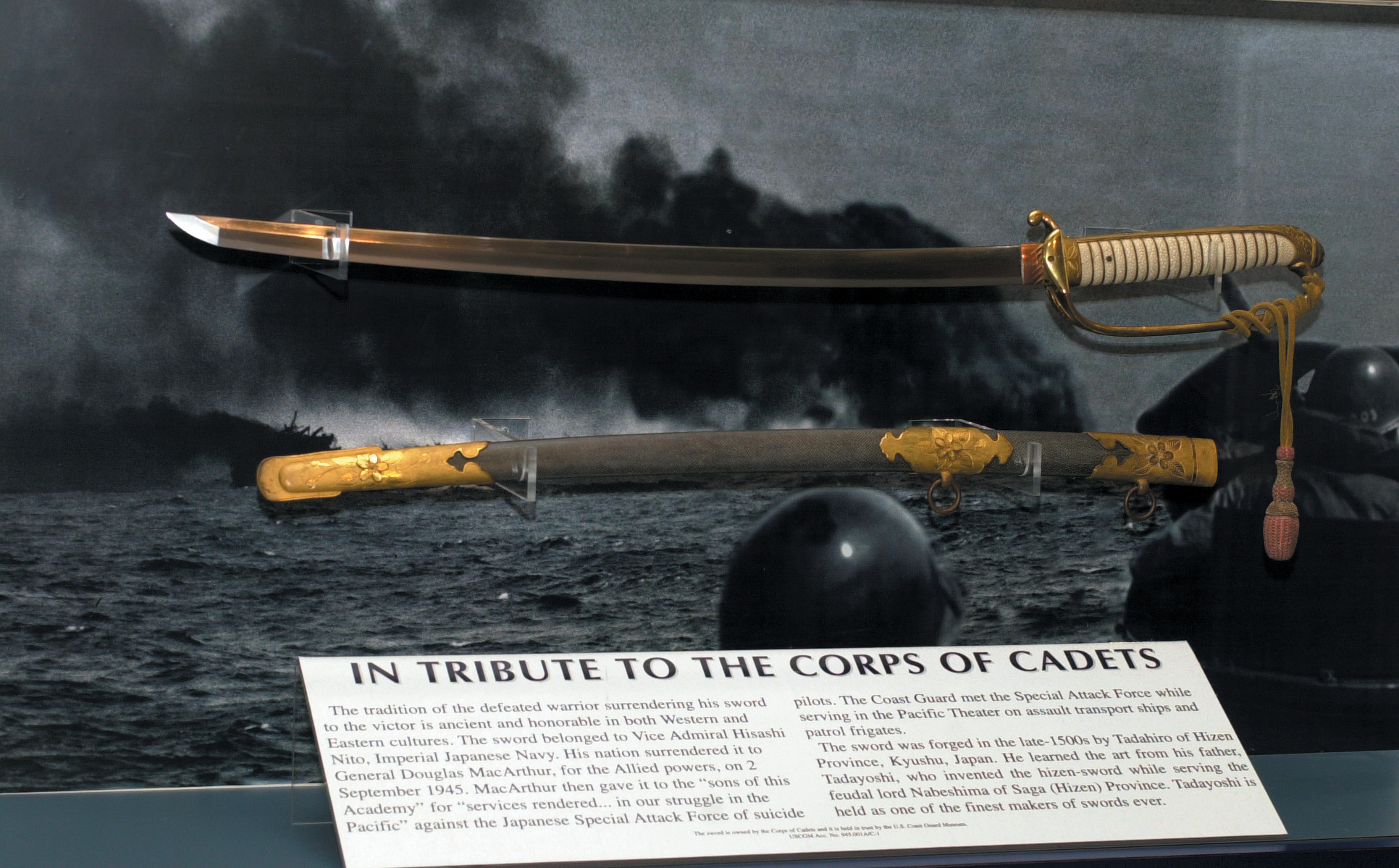

Waesche Hall is the home of the Coast Guard Museum, and houses some 6,000 works of art and artifacts. Among the holdings are a 13-foot, first-order Fresnel lens from the Cape Ann Lighthouse in Massachusetts; signatures of Presidents George Washington, Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy; and some 200 ship models. The admissions offices to the Academy are also located there. Current exhibitions include many of the highlights from the collection. Featuring everything from models of a series of early steamships to the 270-foot cutter that plies the water today, the exquisite craftsmanship of its artifacts captures the changes in ship design over the last 200 years. “For figurehead buffs and wood carvers alike, the museum offers a small but choice collection of carvings,” notes museum curator Cindee Herrick. “Of special value is the figurehead from the Coast Guard’s training ship Eagle. One of the largest figureheads displayed in an American museum, it hangs as if mounted on the bow of a ship.” Cannons, paintings, uniforms, and medals round out the museum’s displays.

Around the Campus

A stroll through the grounds of the Academy, watching the flag raising and lowering, attending a chapel service, reading the memorial in the park overlooking the Thames River, walking the deck of the Eagle, and reviewing the Corps of Cadets, immerse those who visit the Academy in the Coast Guard and its many predecessors—the Life Saving Service, the Steamboat Inspection Service, the Lighthouse Establishment, and the Revenue Cutter Service.

There are several other points of interest on the Academy grounds. Bertholf Plaza, completed in 1992, is named after Ellisworth P. Bertholf, the first commandant of the modern-day Coast Guard. The plaza is the site of several plaques commemorating Coast Guard personnel who served in the Second World War. Chase Hall, the largest Academy building, serves as the barracks for some 900 cadets and officer candidates. It is named after Civil War Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase. Hamilton Hall, named after the nation’s first secretary of the treasury, Alexander Hamilton, houses the offices of the superintendent, the dean of academics, and other administrative offices of the Academy.

On the flagpole across the street fly the national and Coast Guard ensigns, first displayed by the Coast Guard in the 1790s to identify them as federal law enforcement vessels. Satterlee Hall is named for Captain Charles Satterlee of the Class of 1898, commanding officer of the Tampa during World War I, a vessel sunk by a German U-boat with the loss of all hands. It contains the Humanities, Mathematics, and Management departments.

The Coast Guard Memorial Chapel, located on the highest point of the Academy grounds, serves as a reminder of the sacrifices that Coast Guard members have made to their country. The lighthouse lantern installed in the chapel’s spire flashes the Morse code symbol for alpha, the traditional guide to refuge in a safe harbor. Beneath the lantern is the fencing reminiscent of the widow’s walk, where many years ago the wives of seafaring men paced while anxiously looking seaward.

Next to the chapel is the crypt of Hopley Yeaton, the first commissioned officer of the Revenue Cutter service, who originally was buried in Lubec, Maine. In 1975, when his burial site was threatened by construction, the Corps of Cadets sailed the Eagle to Lubec and brought his remains home to the Academy. Behind the chapel is Robert Crown Park, home to several Coast Guard monuments, among them the Wars and Conflicts memorial, a black granite obelisk depicting maritime scenes. Further down Tampa drive is the Coast Guard Academy Visitor Center.

Roland Hall is named after Admiral E.J. Roland, Class of 1929, who once served as commandant of the Coast Guard. The building was completed in 1967 and is still one of the most modern and well-equipped athletic facilities in all of New England. The Cadet Memorial Field is a football stadium named for cadets who have died in the line of duty. Jacob’s Rock, the seamanship center by the Thames River, is visible from the stadium. It was completed in 1984 and is used for teaching sailing and seamanship skills.

Leamy Hall is named after Rear Admiral Frank Leamy, Class of 1925, who earned the Distinguished Flying Cross for a daring rescue of a critically injured man from a fishing trawler. The 1,500-seat building contains the auditorium where the Coast Guard Band performs seasonal concerts that are open to the public. The large ballroom in Leamy Hall, where all cadet formals are held, also offers a spectacular view of the lower fields and the Thames River. Johnson Hall is the home of the Exchange and Souvenir shops.

The Coast Guard Museum is located on the grounds of the Coast Guard Academy, 31 Mohegan Avenue, New London, CT 06320, and is open daily except on federal holidays. Admission is free to all. The hours of operation are Monday-Friday 9 am to 5 pm, Saturday 10 am to 5 pm, and Sunday noon to 5 pm. Call for more information: 860-444-8511

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments