By Eric Niderost

It was a colorful spectacle few citizens in San Antonio, Texas, had ever expected to see: a large delegation of Comanches coming in to discuss terms of a possible peace treaty. The date was March 19, 1840—dia de San Jose, or “Saint Joseph’s day” in a city that was still largely Hispanic in custom as well as outward appearance. It was a large delegation, headed by 12 chiefs, along with 35 warriors. The Penateka Comanche mission also included 32 women, children, and old men, a large collection of furs, and a small herd of horses. These were clear signals of the Comanche’s peaceful intentions—women and children would not accompany a war party; and furs and horseflesh were common items of trade.

The chiefs were especially splendid, looking every bit like the “Lords of the Plains” they would later be called. Mounted on wiry Indian ponies, they were dressed in their finest, another signal that their intentions were not hostile. Some chiefs had ornate headdresses of splayed eagle feathers, while others wore buckskin shirts decorated with long ribbons acquired from trade with the whites. Faces were daubed in paint, colorful red vermillion stripes alternating with darker shades.

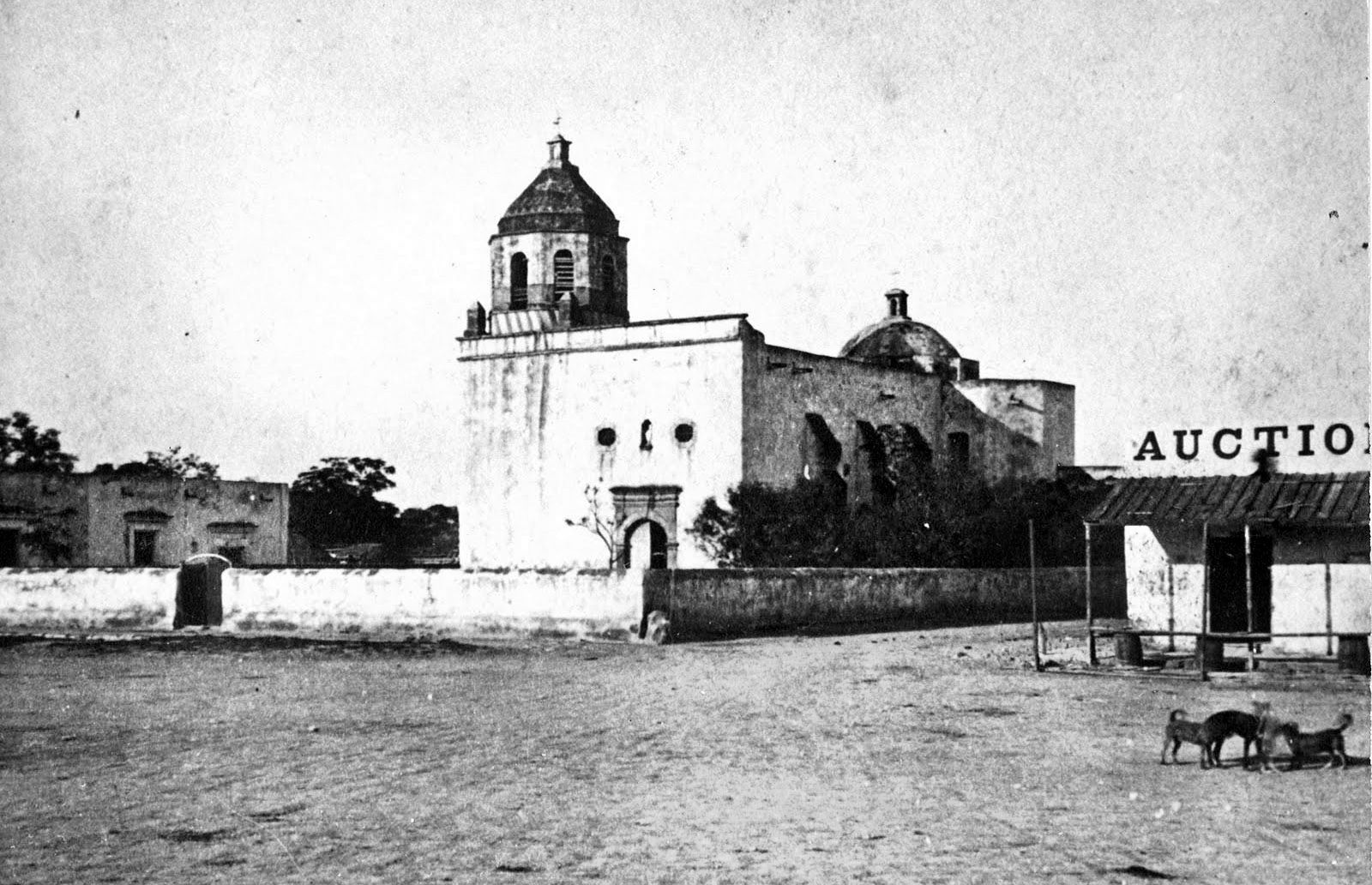

The meeting would be held in the Council House, a one story, flat roofed, limestone building that, along with the adjoining jail, was located at the Main Plaza and Calabozo streets. The chiefs dismounted, and were directed to enter the Council House. Once inside, they sat on the hard packed earthen floor—most natives did not like chairs—while the Texas peace commissioners sat on a raised platform facing them.

A large crowd of San Antonio citizens had gathered outside, perhaps a bit apprehensive but still curious about the new visitors. The Comanche were arguably the most powerful tribe in Texas, with a well-deserved reputation for striking without warning in brutal, bloodthirsty raids that had set the frontier aflame well before the coming of the Anglo Texans.

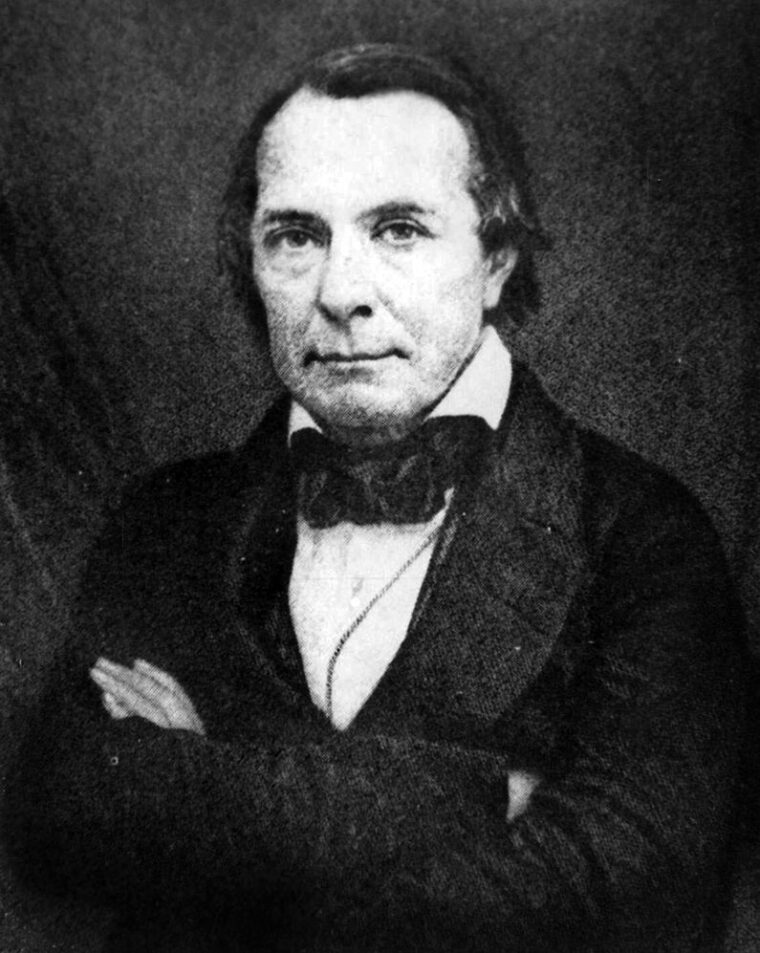

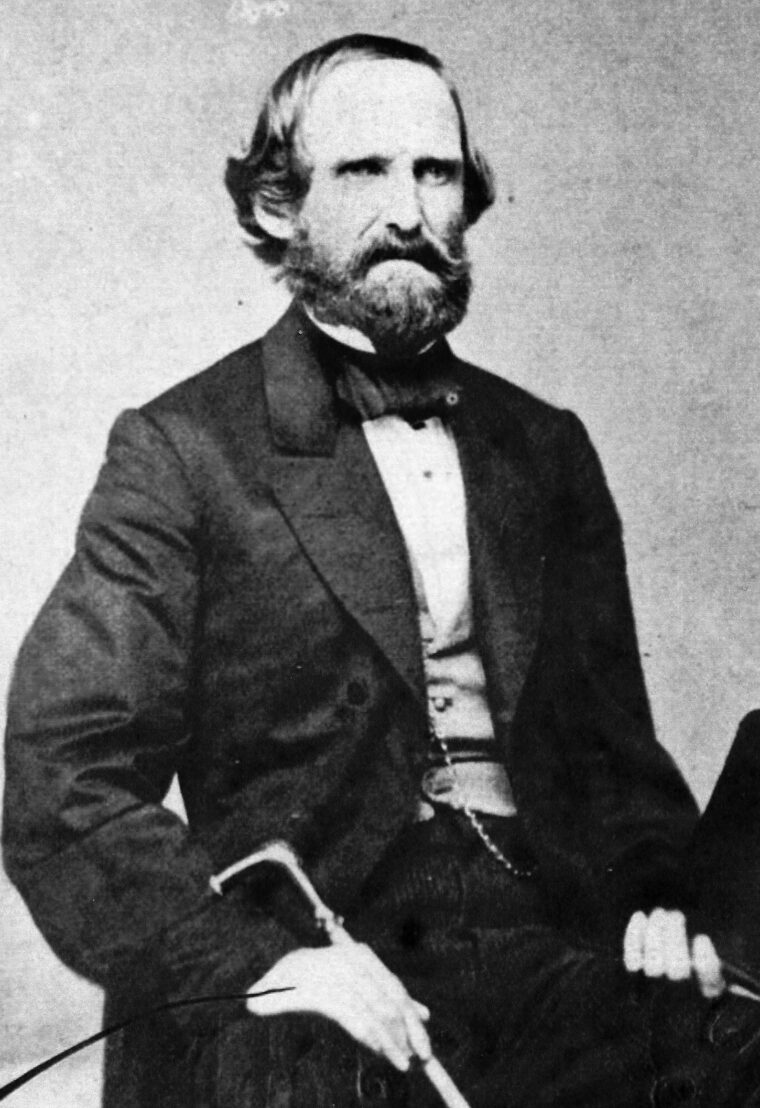

One of the main issues in this conference was the return of white captives taken in various raids. This was not a request, but a demand, and part of the hardline policy promoted by Texas President Mirabeau Bonaparte Lamar. His predecessor, Sam Houston, genuinely appreciated Indians and sought peace with them. But Lamar, like his namesake Napoleon, dreamed of empire—only his version was an all-white empire devoid of native peoples.

Lamar was the brutal, uncompromising face of westward expansion. Gone were the diplomatic niceties, the high flown rhetoric of brotherhood and assimilation. Lamar’s policy was ethnic cleansing, where native peoples had two choices: expulsion or extermination. The Cherokee were his first targets; in the summer of 1839 a village was attacked and many Indians, including Houston’s friend Chief Bowles, were killed. Corn fields were torched and villages destroyed. Other tribes also felt Texan persecution, including the Delaware, Shawnee, Kickapoo, and Creeks. Survivors went north to what is now Oklahoma.

But Texans would soon find the Comanche were a people every bit as determined, warlike, and ruthless as themselves. Part of the unfolding tragedy stemmed from the vast, and ultimately irreconcilable, differences in values, assumptions, and cultural norms. The Comanche shared a common language and culture, but were otherwise completely autonomous. There were five major bands; the group closest to white settlements were the Penateka (“Honey Eaters”). The settlers never seemed to grasp that a chief did not have absolute power over his people. A chief might be respected and followed in battle, but there was no obligation to listen to what he had to say—or follow his orders.

In the first quarter of the 19th century the Comanche had carved out a huge territory that might well be described as an empire. Called the Comancheria, its borders were imprecise, but very real, about 250,000 square miles of plains that stretched from the Arkansas River in the north to the Balcones Escarpment in the south. The escarpment is a fault line that features a rise of tree-covered limestone hills that are pierced by the Brazos, Colorado, and Guadalupe Rivers

South of the escarpment was the coastal plain that held Anglo-Hispanic settlements like San Antonio. The rivers that cut through the escarpment were highways for raiding and war, but also for trade. The Penatekas were the southernmost Comanche band, and despite the raiding and occasional bloodshed, the near proximity to white culture was slowly but inexorably changing them, in good ways and bad.

White clothing made of cotton or wool became more desirable than skins, and metal pots and kettles were better than clay for cooking. Many knew Spanish, and some even learned English. But as the white settlements encroached on Penateka lands, the buffalo were scared away, and soon even smaller game grew scarce. As Chief Muguara (“Spirit Talker”) once lamented, “The white man comes and cuts down the trees, building houses and fences, and the buffalo get frightened and leave and never come back…”

Worst of all, the white settlers brought epidemics of disease. The Americas had been isolated from the rest of the world for thousands of years, so indigenous peoples lacked any kind of natural immunity. The Comanche were regularly decimated by outbreaks of smallpox. The Penatekas decided the best thing to do was to make peace. Perhaps, if all went well, some kind of a recognized boundary between the Comancheria and the Republic of Texas could be established once and for all.

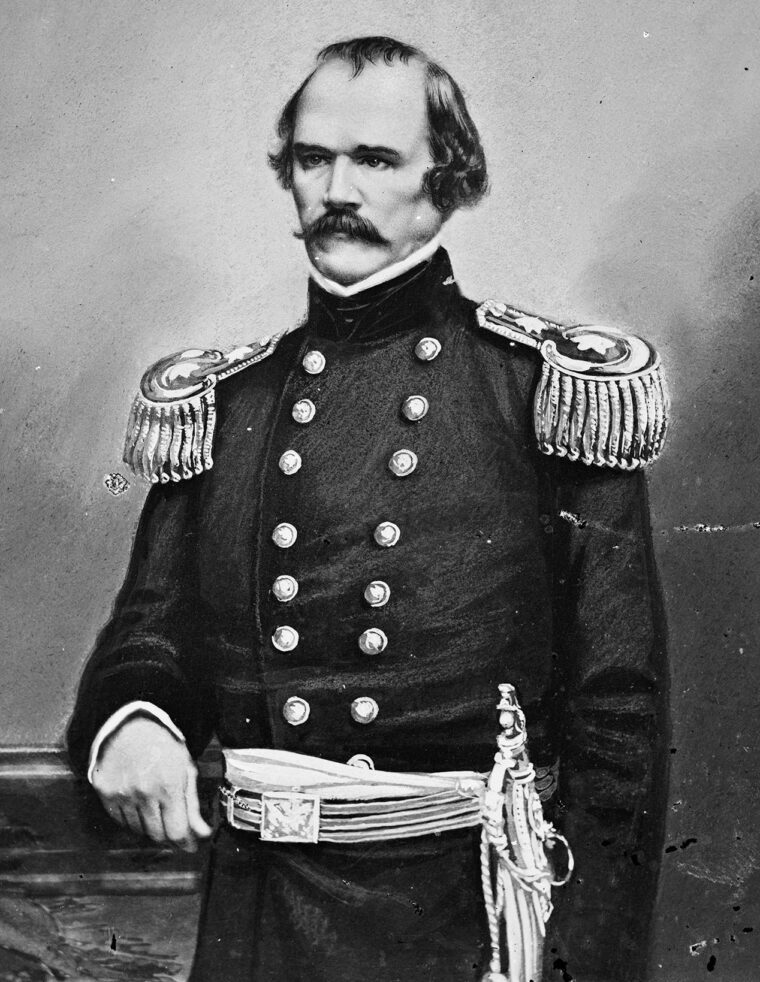

The Texas Secretary of War, Albert Sydney Johnston, was another official who thoroughly agreed with Lamar’s extinction or expulsion policy. He was willing to send representatives to

San Antonio for a parley, as long as the Comanche fully understood that “our citizens have the right to occupy any vacant lands of the government, and they must not be interfered with by the Comanche.” In other words, there was no such thing as tribal lands—all was open to white settlement.

Johnston also made it clear that the Comanche were to immediately return all white captives that they might be holding. If they did not immediately comply, Comanche negotiators would be held hostage until such prisoners were freed. One would think that in such a parley some kind of safe conduct would be granted, but not in this case. To Johnston and many Texans, natives were savages that were beneath contempt, so civilized rules and courtesies did not apply to them.

Lamar appointed Colonel Hugh McLeod, Adjutant General, and Col. William G. Cooke to be the San Antonio Conference commissioners. Expecting trouble, Company A, I, and E of the First Regiment of the Army of the Texas Republic would also go to San Antonio in case the Comanche proved uncooperative. The three companies totaled about 175 men, more than enough to handle the situation if the need arose.

After the chiefs dismounted and entered the Council House the rest of the delegation—younger men, women, and even a few children waited outside. Young Comanche boys of 8 or 10 demonstrated their skill with the bow and arrow, much to the delight of the curious San Antonians gathered to witness the event. When coins were tossed into the air, the boys shot them out of the sky in full flight.

Mary Maverick, wife of a San Antonio merchant, and another woman resident peeked through a picket fence nearby to watch the “performances,” marveling at the skills displayed by children so young. There was no inkling of the, as Mary later put it, “horrors” to come.

Inside the council house the atmosphere was initially cordial, but a palpable sense of unease began to fill the room. The Comanche had earlier promised to return all white captives, but had brought in only one girl, 16-year-old Matilda Lockhart. Her condition was shocking, because the teenager had been raped and systematically tortured during her months of captivity. Mary Maverick recalled that Matilda’s “head, face and arms were full of bruises and sores” from constant beatings. She had no nose, just two nostrils wide open like a skull, surrounded by a large scab.

The girl’s nose had been burnt off by Comanche women, who took fiendish delight in waking her up by shoving a burning piece of wood in her face. The laughter was general as she screamed in pain. Privately she confessed she was “utterly degraded,” a Victorian euphemism for rape. In spite of her suffering, she was a quick learner who picked up the Comanche language. Understanding their tongue, she knew that some 13 captives were still prisoners.

The Commissioner confronted Muguara who, through a translator, was the chief spokesman of the Comanche delegation. The commissioners demanded to know why more captives were not brought in as promised. Muguara explained that they were held by different camps, and although he was a chief, he had no authority over those other Comanches. But Spirit Talker, in a conciliatory tone, suggested that if the whites produced a large ransom in the form of goods, ammunition, blankets and vermillion, he was sure a deal could be worked out.

Who was telling the truth? Perhaps the other groups really were autonomous, and Muguara had no authority over them. The commissioners likely believed Matilda, who had earlier told them that the Comanche planned to release the captives one at a time in a ploy to get an ever increasing number of goods.

After explaining his version of why no further captives were brought in, Muguara smugly added “How do you like that answer?” Enraged by what they felt was Comanche duplicity, and the sight of the noseless, battered girl, they did not like what he had to say. As the conversation continued, Colonel William Fisher gave the order for Captain George Howard’s Company I to come into the room. As they filed in, a second order was dispatched to Captain William Redd’s Company A to assemble outside in the rear of the building, where many of the younger Comanche warriors were waiting.

The Texans had already decided on a course of action, and Fisher told the chiefs “Your women and children may depart in peace, and your braves (warriors) may go and tell your people to send in the (white) prisoners.” This was not yet translated, so the chiefs looked at the commissioners with neutral expressions on their painted faces.

But the follow-up was even more dangerous: “Those soldiers you see,” Fisher continued, “are your guards. You are prisoners of Texas until our prisoners are returned.” The interpreter hesitated to translate this, knowing full well that the Comanches would make an immediate effort to escape. “Tell them!” Fisher ordered, and the interpreter had to comply.

In response, the Comanches let out a collective unearthly howl of rage and the 12 chiefs sprang up and dashed in every direction, each seeking a door or window or any possible avenue of escape. One chief tried to burst through the back door, the portal guarded by Private Martin Kelly. The sentry tried to present his musket, but the Indian’s knife was faster. As Kelly staggered and seemed about to fall, the door now seemed unguarded, an inviting avenue of escape.

Captain Howard grappled with another chief, who stabbed the officer in the side. “Shoot him!’ a bleeding Howard ordered, and a nearby soldier felled his assailant with a well placed bullet. There seemed to be a pause, however brief, while the surviving chiefs drew their knives and notched arrows into their bows. Colonel Fisher ordered his men “Fire if they do not desist!”

The whole scene now dissolved into chaos, a bloody nightmare of grappling, wrestling, shooting, stabbing men fighting each other at close quarters—Indian war whoops mingled with shouts and curses of the combatants, and the screams and moans of the wounded and dying only added to the horror. Before long the acrid stench of black powder smoke mingled with the sweet and nauseating smell of blood.

No quarter was asked or given. This was the frontier; even townsfolk were armed and knew how to defend themselves. As the fight progressed John Hemphill, a lawyer who had recently been confirmed as a judge, found himself battling for his life with a chief determined to escape. It was a struggle, but Hemphill managed to use his bowie knife to disembowel the Comanche.

As soon as the Comanche outside heard the first war whoop from the Council House they sprang into action. The Indian boys, so charming a few minutes before, now started to aim their arrows in earnest. Judge Hugh Thompson and George Cayce were pierced by the “toy” arrows and died immediately. Ironically Thompson had supposedly been one of those who had playfully tossed money for the boys to shoot.

Other Comanche fled through the town frantically seeking to escape. Mary Maverick raced home and bolted the door seconds before a Comanche warrior grabbed the outside handle. Mathew “Old Paint” Caldwell, a veteran Indian fighter, was wounded in the leg early in the fight and found himself hobbling around the streets looking for a gun. When a Comanche warrior raised his bow to shoot an arrow in him, a quick-thinking Caldwell took a rock and flung it, hitting the native’s head with such force it stunned him. Old Paint hurled more rocks, spoiling the Comanche’s aim, till another Texan shot the bowman.

It was all over within half an hour. All Comanche were allowed a chance to surrender—if they did not, they were gunned down or otherwise dispatched without mercy. As might be expected, casualty counts vary, but it seems that 30 warriors, three women, and two children were dead. The rest of the Comanche party, 30 women and children, were in custody. Seven settlers were dead and 10 wounded.

A Comanche woman was released, given a horse, and was told to act as a messenger. The surviving Comanche were now hostages, pending the release of the remaining white captives. But when the Comanches heard the news they were immediately plunged into paroxysms of despair and grief. The loss of so many was a catastrophic, almost apocalyptic event.

They grieved in Comanche fashion, cutting their hair, in some cases mutilating themselves by chopping off fingers, and sacrificing horses owned by the dead chiefs. Then, as anger replaced grief, they turned on the 13 white captives with a vengeance. They were all staked out and slowly tortured to death by burning and painful mutilation. No captive was spared; even Matilda Lockhart’s six-year-old sister was tortured to death.

After a few weeks another chief, Buffalo Hump, had a vision in a dream. For many indigenous tribes, dreams were another world, every bit as concrete and physically real as the reality of everyday existence. Spirits would often communicate via dreams, and a powerful dream was good “medicine” whose message the dreamer would be ill advised to ignore.

Buffalo Hump’s dream was of a Comanche sweep through Anglo Texas, a great raid that would push the white invaders into the sea. It would be a cleansing on a vast and irrevocable scale, so thorough that even the memory of white people and their works would be erased forever. This would be no ordinary raid, but a real invasion of territory far from the Comancheria.

The next step was to recruit warriors for the incursion. The northern bands—the Yamparika, Kotsoteka, and Nokoni—were unenthusiastic and Buffalo Hump only got a few recruits from them. These northern bands had their own problems, including fighting the Cheyenne and Arapahos for the prime buffalo grounds between the Arkansas and Canadian Rivers. Besides, white lands seemed to be full of mysterious diseases like smallpox.

Nevertheless Buffalo Hump’s own band, the Penateka, seemed more than willing to fulfill what amounted to a kind of prophecy. Penateka chiefs like Isimanica, (“Little Wolf”), and the curiously named Santa Anna were always ready for a good fight with the hated whites, especially after the San Antonio massacre. To the Comanche, captives might be adopted into the tribe, but torture, abuse, and rape of such prisoners were well within their cultural norms—behaviors that had been accepted long before the whites ever came to the plains.

They could not understand why the Texans were so outraged over Matilda Lockhart. On the other hand, the Comanches felt that peace negotiations involved a kind of safe conduct for all parties. In their view the whites had treacherously broken this truce. The wide chasm between white and Comanche cultures was too great for mutual understanding.

After weeks of preparation, Buffalo Hump was ready to launch the great raid. He had something like 400 to 500 warriors, and perhaps 600 women and children. The women and children would provide a kind of logistical support. It was hoped, for example, that many horses would be captured, and these prize herds would be driven by younger Comanches.

The great raid began on August 1, 1840, with Buffalo Hump leading no less than 1,000 Comanches. They passed the rocky limestone cliffs of the Balcones Escarpment, then rode down the tree lined Blanco River to its confluence with the San Marcos stream. The Comanche host pressed on, until they were into the blackland prairie of south-central Texas.

The goal for Buffalo Hump and his army was the very heart of Anglo Texas, a scattering of towns and villages that clustered around the rivers and creeks, and continued through grassy plains to the Gulf coast. To escape detection the Comanche started to travel only by night, and by August 4 their nocturnal journey was aided by a full moon. Such lunar aid was a staple even on smaller raids, so much so that the full phase of the moon was called “Comanche moon.”

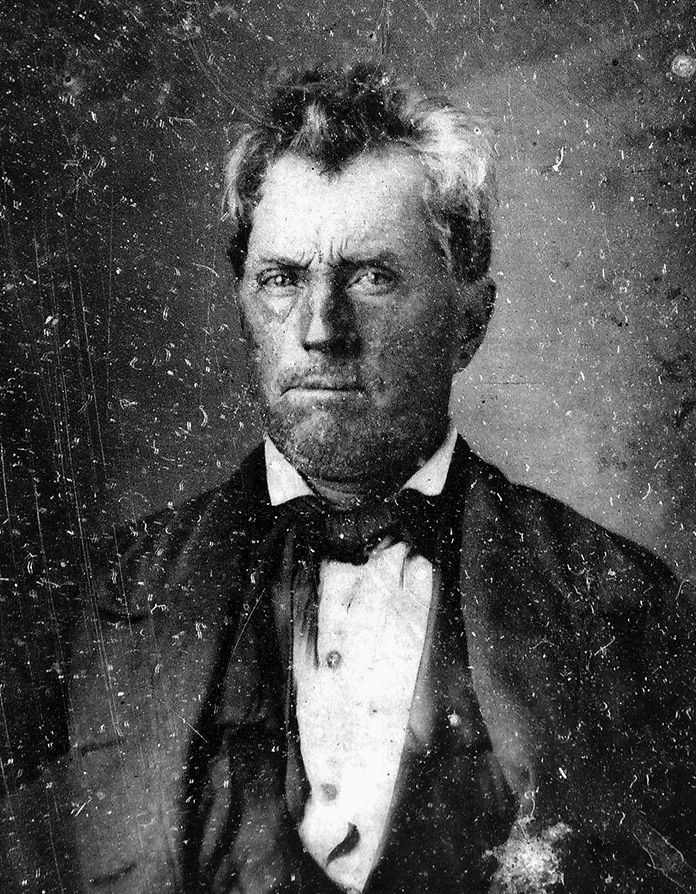

A rural mail carrier was the first to stumble upon the Comanches’ trail, and he spurred his horse to the town of Gonzales to raise the alarm. Ben McCullock of Gonzales was a legend in his own time, a seasoned scout, able frontiersman, and captain of Texas Rangers. A friend of the celebrated David Crockett, he had commanded the “twin sisters” artillery pieces at San Jacinto, the battle which won Texan independence from Mexico.

McCullock responded with alacrity, even though he was partly disabled, his arm in a sling from a duel some time before. He managed to muster 25 rangers and volunteers and immediately set out to locate, and ultimately follow, the Comanche caravan. More men joined as time went on, but even with these additions McCullock only had 125 men, a combination of rangers, militia, and volunteers from nearby farming communities.

In the meantime, the Comanche invasion was amply fulfilling Buffalo Hump’s prophetic vision. At first the depredations were random, the killings a matter of the victims being at the wrong place at the wrong time. Joel Ponton and Tucker Foley were on horseback not far from the town of Hallettsburg on their way to Gonzales. As soon as they caught sight of the Comanches they dug in their spurs and launched into a furious gallop to escape their pursuers.

The Comanches gave chase, and Ponton was hit by an arrow with such force he was knocked from the saddle. Being unhorsed proved his salvation, because he was not badly hurt and could successfully play dead. Foley tried to elude the Comanches by dismounting and hiding in a creek. Unfortunately they discovered him, threw a rope around him, and dragged him from the water.

As soon as Foley was secured, they cut off the soles of his feet, then forced him to walk over rough ground. When they tired of the cruel sport, the Comanches killed and scalped him. Ponton managed to survive and make good his escape—he was lucky that the natives didn’t decide to come back and scalp him, too.

Victoria was a small town of a few hundred residents located on the Guadalupe River about 50 miles from the Gulf Coast. The sudden appearance of hundreds of Comanche took the townspeople completely by surprise, and at first they were mistaken for Lipan Apaches, natives who were friendly and sometimes came in to trade. When the Victorians realized their mistake, they rushed back to their homes and businesses to close doors and “fort up” as best they could.

After the first shock, about 50 townsmen rallied in an effort to prepare for an all-out Comanche assault. Fortunately for the town, Mexican traders had been visiting and their herd of 500 horses were nearby. The horse was a form of wealth to the Comanche, and the sight of so much prime equine flesh was irresistible. The town was momentarily forgotten while the warriors gathered up all the horses they could find.

After some skirmishing and the burning of a house on the outskirts of town, the Comanches withdrew to Spring Creek about a quarter of a mile from Victoria and camped for the night. Grateful for this lull in the fighting, the citizens elected John Polen, an old Indian fighter as their leader to organize a defense.

Most of the Comanche killings were on the outskirts of Victoria. Two black slaves had been killed while cutting hay in the fields, and a black girl kidnapped. A Mexican riding a mule was caught and quickly dispatched, but two other riders, Joseph Rogers and Jesse Wheeler saw the Comanche in time to gallop away and escape.

The Comanche did some skirmishing the next day, but out-and-out assaults were simply not their style of fighting. Mrs Nancy Crosby, said to be the granddaughter of Daniel Boone, was taken prisoner with her baby son in a farmhouse not far from Victoria. Some sources say she had two children, but all versions agree on her tragic fate. When her baby cried too loudly a Comanche snatched the infant from her arms and smashed its head against a tree, instantly killing him. When the second son, a toddler, also cried, he was killed with a spear in front of his horrified mother.

Linville was a small coastal port town of about 200 residents. It may have been physically small, but it loomed large as a link to the outside world via sea trade. Its warehouses were bulging with goods, including clothing, that were otherwise hard to obtain on the frontier. The Comache burst into the town like avenging furies, once again taking the inhabitants by surprise. Greatly outnumbered, the citizens fell back to a lighter— a small coastal craft—that took them to a schooner anchored in the bay.

A few did not make it to the safety of offshore boats. Customs inspector H.O. Watts was caught and killed, and his wife—a “remarkably fine looking woman” according to one witness, was taken captive. The Comanches tried to strip her, but were both baffled and frustrated by her whalebone corset. Unable to take the contraption off, they simply strapped her on a horse and took her with them.

The townsfolk in the schooner and other craft—some sources say they were a few boats anchored in the shallows 100 feet from shore—watched as helpless spectators to the destruction of their town and their livelihoods. The Comanches turned their attention to the town warehouses, which were bugling with all sorts of interesting things from the white man’s world. Businessman John J Linn recalled that “in my warehouse were several cases of hats and umbrellas belonging to Mr James Robinson, a merchant of San Antonio. These Indians made free with…”

After each warehouse was thoroughly looted, it was put to the torch. Private homes were also ransacked then burned. Comanches decorated their ponies with ribbons, and wore Texan clothing as they shouted triumphantly and galloped up and down the smoke-darkened streets. Comanche women participated, carrying armfuls of loot to waiting pack horses, and native children raced up and down the street laughing and screaming as youngsters do when they play.

It became a sartorial saturnalia, as the Comanche reveled in the splendor of their frock coats, hats, and umbrellas. While they paraded with gleeful abandon, orange flames consumed the buildings, sending up coils of black smoke into the sky. Judge John Hays was so incensed at helplessly watching the conflagration he jumped overboard—it was only 3-4 feet deep at his location—and waded ashore with a gun.

Surprisingly the Comanches gave him a wide berth. It was so foolhardy for a single man to confront 500 warriors. The Indians must have felt he was either crazy or had special “medicine,” so it was best to leave him alone. Only later did Hays realize how lucky he was to be spared—the gun had not been loaded.

From the Comanche point of view, Buffalo Hump’s vision had been fulfilled. They had killed perhaps 20 people—maybe a few more—but now could come back to the Comancheria with what to them was an enormous amount of booty. First and foremost, they now had perhaps 3,000 captured horses, each mount more valuable than gold in their eyes.

But the Comanches were now a long way from home, and the sheer immensity of their caravan meant it was relatively slow and easy to track. The element of surprise was gone, and the Texans were rapidly marshaling their forces to confront them. Initially the Comanches, perhaps dazzled by all the loot, seem to have given little thought as to what might happen on the return journey. Perhaps they thought the whites were cowed; certainly there had been relatively little resistance up to then.

The emergency brought out all of the men— Ansome with Texas Ranger experience, some not—who were veterans in Indian warfare. “Old Paint” Caldwell, so-called because the white specks in his dark beard matched his mottled paint horse, was one of these. Other former ranger captains included John Tumlinson, Adam Zumwalt and General Ed Burleson. Burleson brough 87 volunteers with him and his command included Chief Placido and 12 Tonkawa Indians on foot.

Caldwell and his men reached Plum Creek the evening of August 11, and were greeted by a company of men under Captain James Bird. Ben McCulloch and his brother Henry were with Bird, but now serving in the ranks, not as independent scouts. Major General Felix Huston of the Texas Republic Militia was also on hand.

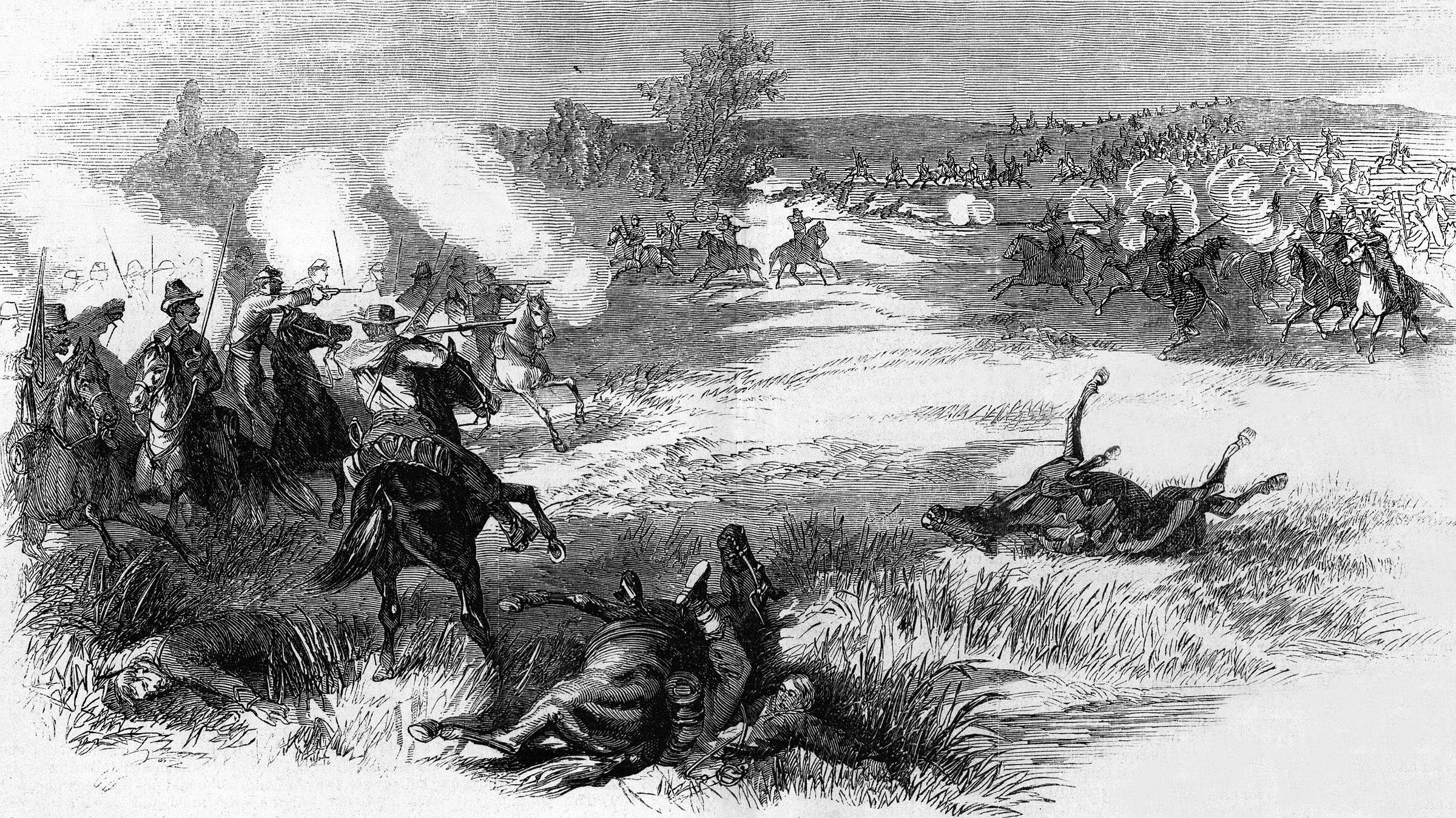

The clash now known as the Battle of Plum Creek began the next morning, August 12, 1840. The Comanche caravan had been spotted lumbering across Plum Creek. At one point the tribal column’s advance elements were anchored in a stand of oaks, but the rest of the caravan were exposed and stretched out on open ground, the whole no less than three quarters of a mile long.

There was a pause while the senior ranking officers sorted out who was going to assume overall command of the Texan force. General Huston moved forward to a ravine on the edge of the prairie, and prepared to attack, only to halt when a message gave him word that General Burlson was only three miles away.

The Comanches now realized they had been discovered, and immediately started to organize defensive measures. To a novice the warriors seemed haphazardly armed—with bows and arrows, trade muskets, and a few modern guns taken at Linville. The trade muskets were notoriously inaccurate, and the modern guns were too few in number to tip the scales in the Comanches’ favor. However a warrior could launch five arrows before a Texan could reload his gun, a decided advantage before the Colt “Walker” revolver was introduced later in the 1840s.

Huston formed the Texan command into three elements, with a fourth in the rear as a reserve. They dismounted about 200 yards from the Indians, and firing between the two opposing sides became general and very brisk. Several Texans were wounded in the exchange, presumably mostly from arrows, though the few looted guns might have scored hits.

But then the Comanches put on a show of horsemanship that produced a grudging but sincere admiration. As scores of warriors circled around the space between the two sides, James Wilson Nichols remembered them “Lying flat on the side of their horse with nothing to be seen but a foot or a hand, they would shoot their arrows under the horse’s neck, run to one end of the space, straighten up, wheel their horses, and reverse themselves, always keeping on the opposite side (hidden) from us.”

The Comanches pumped up the adrenaline and prepared for the fight by blowing eagle bone whistles and singing war chants, a blend of surreal music to the whites, but a means of bolstering courage to the assembling Comanche warriors. As they blew their whistles and chanted rhythmically, they fanned out and imposed themselves between the Texans and the Comanche caravan.

In spite of the deadly fusillade of arrows and bullets, the scene had an almost festive air, with the Comanches arrayed in mixed-culture costumes never seen on the plains before or since. Nichols wrote that there was one chief with a traditional horned buffalo head cap, but with “ten yards of red ribbon” streaming from each horn. Another chief had “red top boots, blue cloth pants,” and a coat worn in reverse with “the hind part before and buttoned up behind.”

It was a dazzling array of both horsemanship and “fashion,” but there was one chief who outshone the rest in sartorial splendor. “He was riding an American horse…with a red ribbon eight or ten feet long tied to the tail of his horse. He was dressed in elegant style…with a high silk top hat, fine pair of boots and leather gloves, an elegant broadcloth coat, hind part before, with brass buttons shining up and down his back. When he first made his appearance he was carrying a large umbrella stretched.”

About 30 Texans remained mounted while the others fought on foot, and it was these riders who dashed forward to exhibit their own brand of superb horsemanship. The fighting continued, as bullets and arrows filled the air, and at one point Henry McCulloch dismounted near a mesquite tree in order to take a better aim and, as he colorfully said later, “git a fair pop at one of those fine dressed gentlemen.”

But he was too far forward, and Nichols alerted Henry’s brother Ben that his sibling was in a dangerous position. As Ben rode forward to rescue his erring brother, a chief wearing a buffalo headdress spotted Ben and approached at a gallop. Seeking to give Ben covering fire, Nichols was just in the process of pulling the trigger when an Indian bullet slammed into his hand, ruining his aim. The bullet from the Nichols gun, thus deflected, killed the chief’s horse and buried itself deep in the native’s thigh. Undaunted, the chief rolled from under his horse and tried to hobble to safety, but another Texan finished him off.

But Comanche men nearby saw what happened and tried to reach the body of their dead chief to carry him off. The attempt resulted in a furious clash within the larger battle, as Texan and Comanche horsemen maneuvered their mounts and fought at close quarters. This time the Comanche got the worst of the encounter; about a dozen warriors were killed, and the chief’s body still lay where he fell.

It was at this stage that one of the Texans, a man named French Smith, had had enough.

“Boys, let’s charge” he declared in a loud voice that could be heard over the din of battle. The men around him responded with alacrity, and soon other Texans mounted up and went forward in a headlong advance. Hit in the front and in the flank, the warriors began to waver and fall back.

As the Comanche protective screen began to melt away, the Texans started to reach the rear elements of the actual horse herd and pack horse caravan.

Panicked by the Texan horsemen, who were not only shooting but screaming at the top of their lungs, the captive horse herd began to stampede. This tidal wave of frightened horseflesh slammed into the column of pack animals, beasts of burden already mired in muddy ground. The result was pandemonium that sent the panicked Comanches fleeing.

The Texans had held their fire until the last moment, then unleashed a broadside of bullets so effective no less than 15 Comanches were killed and wounded within seconds. Elated by this turn of events, the Texans refused to draw rein, declare victory, and call it a day. Determined to teach the Indians a sanguinary lesson for all time, they followed the retreating Comanches for a further 15 bloody miles.

The battle of Plum Creek was over, and with it, the Buffalo Hump great raid. Texan losses were given at one dead, seven wounded, but as always Indian deaths were much harder to tally. Estimates of Comanche dead are given at 25, 50, 80, but these are only guesses. Depending on sources, from 12 to 25 Indian bodies were reportedly found. Lurid stories circulated about the Texan’s Indian allies. Some versions say the Togawas enjoyed a cannibal feast on one Comanche body, or—even more grisly—killed live Comanche prisoners, then ate portions of them.

Some “hundreds” of horses were recovered, and much of the booty, but there is evidence the Comanche didn’t leave the area empty handed. But Buffalo Hump’s dream had become a waking nightmare. The Anglo Texans were not pushed into the sea, and white numbers would increase as the years wore on. The Texan’s claim of a decisive victory also proved illusory. The 1840 fights were just the curtain raiser on a bloody war that would carry on intermittently for the next 35 years.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments