By Steven Karras

Prologue:

Once they escaped from Nazi-dominated Europe, hundreds of German and Austrian Jews joined the American and British military to help bring an end to the Nazis’ reign of terror. Each had faced the shock of the Holocaust, knowing full well that, had they not left in time, they likely would have ended up in concentration or extermination camps.

It was also with considerable courage that they returned to fight the Nazis, for they knew they faced great danger if they were to be captured.

By 1940, approximately 280,000 Jews had left Germany and another 117,000 had left Austria. Of the 95,000 German and Austrian Jews who had immigrated to the United States, it is estimated that 9,500 served in the U.S. armed forces, many in combat units. Nearly 13,000 Jewish refugees—men and women—served in the British armed forces.

These refugees had a firsthand knowledge of the enemy, a nuanced understanding of the psyche of the German people, detailed knowledge of the country, and, of course, skills as native speakers of German.

The Allies used the refugees’ skills and knowledge to gather military intelligence, and many were entrusted with important roles in the occupation of Germany and Austria. Their prominent and fitting roles in frontline prisoner interrogation units questioning the very Nazis who had once persecuted them were essential to the Allied victory.

The extraordinary, if not unprecedented, turn of events and circumstances that led to the impressive number of Allied refugee soldiers during that period was best summed up by historian Arnold Pauker, a former German refugee and soldier in the British Army: “It is terrible to have to say this but in one respect we German Jews were quite lucky that Hitler came for us first. This meant that the majority was able to flee or immigrate in time, and among this number the younger generation was heavily represented. When the war broke out, there were many of military age, who had been waiting for an opportunity to fight against Nazi Germany.”

Here is their story, in their own words.

Siegmund Spiegel

1st Infantry Division, SHAEF Headquarters, Gera, Germany

“Early in August 1944 the breakout of Normandy occurred. After the fall of St. Lô, a city that, for all intents and purposes, was totally destroyed, the lines became fluid. It was then when, on August 7, 1944, having learned that German Army headquarters near Mayenne had been overrun, our team was to proceed to the Third Army G-2 (Intelligence) Section. By the time we reached there, the front line had again changed, and instead, we were to head toward Falaise.

“We made our way down into a valley on a one-lane farm road when the ‘burp’ noises of German sub-machine guns became nearer and nearer. It was there I told to my captain, Curts, my observation that the valley was ‘too still.’ Even with the noises from small-arms fire, it gave this whole scene a feeling of eeriness. I even recall using the German word unheimlich then.

“Just then all hell broke loose. Maybe seconds, maybe minutes, had elapsed when I found myself raising my head and looking around. Our jeep stood mangled across the road with me 20 yards distant from it. Captain Curts was lying on the road, his legs inside his combat boots swelling, seeming to burst the leather. The corporal, Trombley, was crouching in a ditch and bleeding profusely from his right hand where shrapnel had penetrated it.

“At first impulse I thought we had a direct hit from an artillery shell. I crouched over the captain, trying to administer first aid to whatever extent possible, while Trombley was tying a tourniquet around his arm. I knew then that we had hit a Teller Mine [13 pounds of explosives]. I turned quickly, even certain of hearing German voices near me, and made my way back.

“I was sent to the field hospital where I was admitted with multiple contusions and injuries to my left knee and ribs, blast burns, and shock. The captain’s legs were both shattered. There I was on a cot in a tent when the German counterattack was underway (capturing one of our field hospitals). Convoys of ambulances brought heavily wounded GIs in, and they remained on their stretchers set on the barren floor. When I saw this happening, I called the hospital administration officer and asked to be discharged, since my condition was not anywhere as serious as the men who didn’t have a cot.

“That morning, an orderly came with a batch of Stars and Stripes that had just arrived from England. In it I saw a brief item that got me very excited: the Russian Army had liberated Lwów, a city in Poland where I knew my parents had last lived. Of course, I was not aware then of what had happened in the interim to Jews, including my poor parents.

“Just then a Red Cross girl entered our tent asking us whether we needed writing paper, razor blades, or whatever else she had on hand to distribute. I asked her, ‘You are with the American Red Cross, right? You have contact with the International Red Cross?’ When she nodded her response, I showed her the article in the paper, gave her my parents’ names and last known address in Lwów, and asked her to immediately initiate steps to locate them through the International Red Cross.

“She looked at me as if I were shell shocked, not having expected that a wounded soldier would worry about something happening on a front far removed from current combat in Western Europe. I assured her that I had all my senses and got her assurance that I would hear from the Red Cross. Sixty-nine years later and I am still waiting.”

Henry Kissinger

335th Infantry Regiment, 84th Infantry Division, Division Headquarters, G-2, Fürth, Germany

“I went overseas with the 84th Infantry Division, first to England and then to France, where we landed at Omaha Beach in early September, after the breakout of Normandy. We then went to the front on the border of Germany and Belgium in November, and our regiment was assigned to the 30th Infantry Division for combat experience.

“Combat is usually an ordinary experience of extreme boredom, followed by moments of intense danger, but the period of intense danger is very short. I initially came to the front as a rifleman. Then one day, while I was on latrine duty, an encounter happened that changed things. The man in charge of latrine duty had to keep the situation map––which was in the dayroom––of where the front was.

“Our general came by for inspection and said, ‘Soldier, come over here and explain this map to me.’ I translated it and he said, ‘What are you doing in a rifle company?’ I must have said, ‘I don’t know. I was assigned here.’ So, while we were still on the front lines, he gave an order to pull me back to his headquarters, but this wasn’t executed for a while, so I remained at the front.

“After we had left the 30th Division, I reported to division headquarters for the G-2 Section, which was Intelligence. My job was to capture documents and help interrogate prisoners, though my primary task was to look after security, catch spies, and prevent our documents from falling into enemy hands.

“Once I was more or less assigned to the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC), I was then sent down from division headquarters to regimental headquarters, which was even closer to the front, and I worked on counterintelligence there.

“After that combat phase was over, I was assigned to regional Germany, a county in the American zone of occupation near Frankfurt with a population of about two thousand. My job was to maintain the security of that area and arrest all Nazis above a certain level. I had the right to arrest anybody I wanted for security reasons, which was a strange reversal of roles. Of course, no German ever claimed to have been a Nazi.

“Everything had broken down in Germany; there was no postal service, there was no telephone, there was no communication—a total catastrophe. We in the military had our own telephones to other military posts, but no one could call a German on the telephone. There was a food shortage and a terrible black market. It’s hard to imagine today how a society could break down that completely. At that time, if anyone had shown me a picture of what German cities look like today, I would have said, ‘You’re insane. It would take 30 years just to clear away the rubble.’

“At some level, being back in Germany as a conquering soldier gave me some degree of satisfaction when I saw the people who had been so swaggering now on the other side. But on the whole, I felt that I had a job to do, which, incidentally, I found very interesting. I had always been interested in foreign policy, but I tried to keep my own personal experiences as much out of it as I could.

“After the surrender, the first thing I did was look for members of my family to see whether any of them had survived, but they hadn’t. I went back to my hometown, the place where my grandparents had lived, and that was somewhat of an emotional experience. Having lost many members of my family to the Nazis, I had considerable animosity toward them, but even with this, arresting people and seeing crying wives and children, was no fun. At least it wasn’t fun for me. It gave me some abstract sense of satisfaction but no personal satisfaction.

“For us German refugees, going to war was something that we felt needed to be done, but that we might not particularly enjoy once it happened. For me, however, I now think that it was the most important experience of my life.”

[Henry Kissinger became Secretary of State in the Richard Nixon administration and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his role in ending the Vietnam War.]

Jack Hochwald

6860 HQ Detachment Assault Force, Seventh U.S. Army, Vienna, Austria

“In the second week of March, all of our teams crossed the Rhine—thanks to the courage of an entire infantry company—at a place called Remagen, with one of the last remaining bridges still intact. Also, under heavy fire, Army engineers had constructed pontoon bridges in several other places on the Rhine, which would make for a swift advance into Germany.

“In the second week of March, we were on the way to our first major intelligence target inside Germany. This was the I.G. Farben complex in the twin cities of Ludwigshafen and Mannheim. We would find out that the Farben factory had been deeply involved in Germany’s war effort and had also participated in the manufacture of Zyklon B gas used in concentration camps, but supposedly had not been aware of the great extent and usage in gas chambers operated by the Nazis. When we stormed into the administration building, we surprised the directors, who were having a board meeting.

“We became overwhelmed with targets—anything of intelligence-related business—but we were moving so fast and being attached to units advancing quickly, this made it difficult to stay in one place for more than a day. We found ourselves with the 45th Division, which was closing in on Munich. Along with the 42nd Division, the 45th was on its way in and entered the Dachau concentration camp. As it happens, I was fortunate to be assigned to a Lieutenant Salzman, another refugee, who suggested we go to the camp and offer our help.

“By the late afternoon, we saw the barbed-wire fences and watchtowers, stopping at the main gate with its slogan above that said, ‘Arbeit Macht Frei’ (Work will make you free). An officer came toward us as we were trying to get in, saying that there was a real danger of a typhus epidemic and most Army personnel were prohibited from coming in. So, we decided to ride along the fence for a while, where we now saw inmates in striped clothing standing around and waving to us.

“Upon seeing them, we left our jeep and walked toward a group of men huddled around a fire. We tried to speak to the group we had come upon; we had difficulty since they were Serbs and Croats. It wasn’t very long before several other inmates joined in and, speaking in German and Yiddish, we were able to communicate.

“One of them, wearing the Star of David, asked us when the rabbis were coming, since he wanted to say Kaddish [Hebrew prayer for the dead]. From him, we learned that the day before the first American troops had arrived, blasting their way in and mowing down with machine guns and rifles any of the German guards they encountered.

“He then pointed to several boxcars standing on a rail siding, a couple of hundred yards away, so we walked slowly over there. Soon the stench overcame us, but we managed to see in half-opened boxcars the remains of bodies, reduced to skeletons and bones. We were told that these were only part of a shipment of new arrivals from another camp [Buchenwald] who had not survived the trip due to disease and starvation.

“As we were leaving, one of the Jewish inmates came over to us and, in a low voice, asked us who the Asiatic and Mexican looking soldiers were, whom he encountered the day before. We told him that all of them were good Americans and that among us, too, were former Nazi refugees who only a few years ago had escaped Germany.

“He looked dumbfounded but then understood who we were; he confided in us that he and a few others from his barrack had taken revenge on some of the kapos [block wardens and inmates acting as overseers], especially those who had been cruel. We assured him that he and his fellow prisoners did the right thing, and we would have done the same had we gotten there earlier.

“When the war ended, we again joined the main body of the Seventh Army in Heidelberg. With pressure from the American public and the press, General Eisenhower ordered an operation called Tally-Ho—the code name for surprise raids of supposed hideouts, where we found SS men hiding in attics and barns in Bavaria.

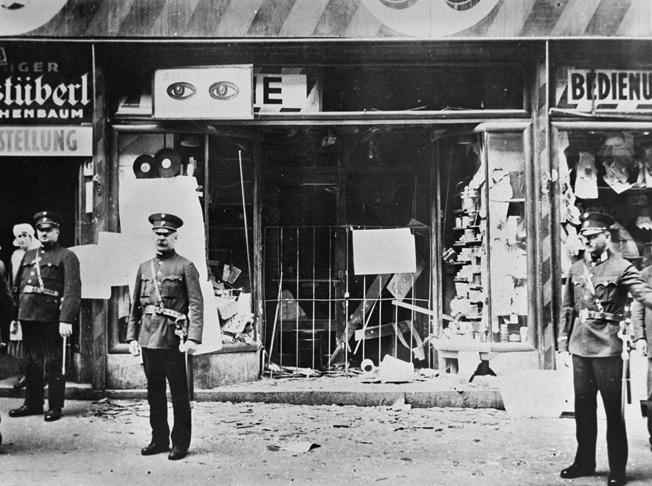

“It may be of interest to note that most of those interviewed and asked where they were on November 9, 1938, on Kristallnacht, when many Jewish homes and shops were looted, synagogues burned, and thousands of Jews arrested and sent to concentration camps, all of them invariably replied that they had been ‘zu haus,’ which meant ‘at home.’ What bullshit.”

Harold Baum

97th Infantry Division, Berlin, Germany

“I saw my first real action near Düsseldorf and participated in the Ruhr Pocket campaign in April 1945.” The 97th crossed the Rhine near Bonn.

“Our first action was in Nois, where my company was selected to send a patrol with assault boats over to Düsseldorf. There were six GIs to a boat, and we were in a permanent state of diarrhea and fright during the entire attack. I kept my head low, trying to reconnoiter the area while under fire, and I made it back.

“We were coming from the west bank of the Rhine, and Germans were on the east bank viciously firing at us. That, of course, was followed by a frenzied attempt to identify from where the shells were coming and direct mortar fire in that direction. The most frightening thing during combat, in which I spent 60 consecutive days, was the uncertainty of where they were shelling us from.

“Fortunately, in our company we had a light machine gun section, a heavy machine gun section, and a mortar section. These people did a marvelous job once we identified a target. Once, we overran a flak position of German 88s; our scout spotted them at dawn and called in mortar rounds on their position. They were slaughtered. The 88s were terrifying weapons because they were used point-blank on us instead of on airplanes. Seeing a kid next to you fall, wounded or killed, was a terrifying experience. I cannot begin to explain the rage I had when seeing German soldiers come out with white flags after an ambush. Needless to say, there were times when we did not take prisoners.

“We encountered fanatical German resistance in the Ruhr Pocket, primarily from the young boys who were 14 and 15 years old and willing to die for Führer and Fatherland. At times we saw people dangling from trees, strung up by the SS, with signs around their necks reading, “Ich bin ein feigling” [I am a coward]. That only intensified things for me.

“I had a unique experience in Solingen where a German lady came to our command post and told us that a German general was hiding out. The captain said, ‘Lieutenant Winsam, Sergeant Miller, Baum, go and get him.’ We surrounded the house. There was this middle-aged man, and I started questioning him. In an almost defiant, arrogant manner, without getting up, he said, “Ich bin Gustav-Adolf von Zangen.”

“Without undue delay I told him, ‘Hände hoch’ [hands up], pointed my rifle at the son of a bitch, and he turned ashen white. Then I told him, ‘Ich bin ein Deutcher Jude’ [I’m a German Jew], and this man was in an absolute state of terror. He could not believe that one little yid should get him out of five million GIs. A rifle pointed at an arrogant officer becomes a powerful persuader. It was a good feeling.

“Gustav Adolph Von Zangen was a lieutenant general, commander of the Fifteenth Army Group. His last command was in the Ruhr Pocket. I escorted him with the lieutenant to division headquarters where he surrendered in a customary procedure, like a soldier, which nauseated me—to me he was a Nazi, not a soldier. General [Milton B.] Halsey, commander of the 97th Division, interrogated him while I was the interpreter.

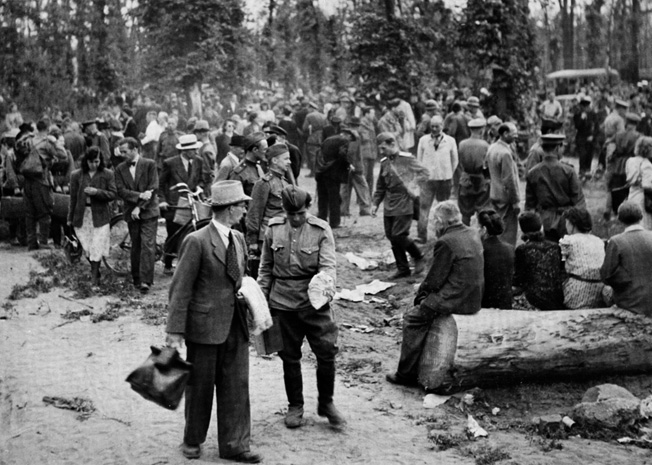

“After we occupied Solingen, there were Russian forced laborers who, after being liberated, went after the Germans, and the Germans wanted protection from the Russians. As you can imagine, we refused and justice was swift.

“After completion of the Ruhr campaign, we were sent to southern Germany and started moving in the direction of Czechoslovakia. On the western border of Czechoslovakia and Germany, we encountered a concentration camp called Flossenbürg and liberated one of the smaller camps of that facility. We saw scores of dying, starving prisoners. It was terrible, and the stench and odor of death I will never forget.

“There were also well-fed prisoners who had on the same inmate uniforms. I unsuccessfully tried to communicate with them in German; one kid in my company spoke Russian and Polish to them and they did not understand that, either. We could not figure it out.

“My captain decided to strip them down and discovered that they had their blood type tattooed under their arm, which was customary practice among SS troops. They went into the mass graves and helped to dispose of all the corpses, but they did not last to face a war criminal trial. The justification for their demise was that they switched uniforms, which under the Geneva Convention is a punishable offense. They remained in the pits with the corpses.”

Manfred Steinfeld

82nd Airborne Division, Headquarters Company, Josbach, Germany

“After the German counteroffensive stopped, we were sent back to base camp in France. In the middle of March, we were assigned to the newly formed U.S. Ninth Army, then holding the west bank of the Rhine in the vicinity of Cologne. We were there until the middle of April, when the 82nd Airborne established the last bridgehead along the Elbe River.

“On May 2, 1945, I was on the reconnaissance patrol that contacted the Russians. At the same time, I was involved in translating the unconditional surrender document; the 82nd Airborne Division accepted the surrender of about 400,000 Germans facing our sector on May 3, 1945.

“We also came across the Wöbbelin labor camp, a sub-camp of a larger Neuengamme concentration camp system. I was certainly emotionally distraught in the camp, because there was always the possibility of seeing my mother and sister among the dead or half-dead. That was one fear I had. When we found the bodies in the camp, we decided to bury them in the nearby town square. I made the funeral arrangements and the American chaplain gave the eulogies.

“The Germans, of course, felt that we were doing an injustice to them by accusing them of these crimes, even though they lived only three miles away. They swore they had no knowledge of the atrocities. ‘We didn’t know’ was the typical German excuse.

“In June, when I was military governor of a town called Busenberg, a woman came up to me in a concentration camp-striped dress. She informed me that a man walking across the street was a criminal, and we arrested and interrogated him. It turned out that his name was Ludwig Ramdohr and he was the assistant commander of the infamous Ravensbrück concentration camp for women, where this woman was an inmate.

“We took him out for target practice and threatened him with our pistols before turning him over to the British military tribunal on June 10. He had a military trial and was hanged by the British three years later.”

Eric Boehm

U.S. Army Air Force, Hof, Germany

“Since there was a shortage of German-speaking officers, I was loaned to the Army side as the interpreting officer for the arrest of Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel. General Rooks, Eisenhower’s representative, called Field Marshal Keitel to the ship in which we were operating to tell him to pack and be ready to be flown away from Flensburg several hours later.

“About 2 pm that afternoon, a Lt. Col. Boehm-Tettelbach and the aide de camp, or adjutant, on Keitel’s staff came to the gang plank of the ship and picked me up so that we could drive to OKL headquarters––the Oberkommando der Luftwaffe [High Command of the Air Force]. We talked very briefly about the coincidence in name; I found out subsequently from my father that the family is from Upper Franconia, the area of Bavaria where I was born. I was rather disinclined to make small talk in any case, because I had some strong feelings, particularly about Field Marshal Keitel.

“He was known as the lackey of Hitler, but I did not know at the time that he was being arrested in anticipation of being held for the Nuremberg Trials, where he would be sentenced to be hanged—deserving this fate—because he was one of the most evil types serving Hitler.

“Keitel was allowed a fairly large number of accompanying generals to see him off at the airport, and our General Rooks had provided four staff cars. I was surprised at the amount of baggage that Keitel took with him––a weapons carrier full of at least half a dozen suitcases, some of them quite large in size. I remember one box that approached the size of a steamer trunk.

“When we arrived at the airport, it turned out that the plane, which was to take Keitel to his destination, had landed and then took off to do some sightseeing of Copenhagen from the air; it was uncertain when it would be back.

“Since it was an unusually warm day, I arranged that the whole group be taken to one of the barracks. Keitel was visibly taken aback by the fact that he had to wait. Since he lacked good understanding as to his new position, he was stupid enough to say to me something to the effect that he had to rush to pack and now he had to wait. I ignored him and certainly did not apologize, but wished in retrospect that I had said something to him to the effect that we had been waiting six years for him, so he could certainly wait a few hours for us.

“Eventually, the American C-47 crew came back and they were ready to transfer Keitel. He was wisely removed to take away the top authority from the OKW. He became a prisoner of war and was placed in one of the holding fortresses, which we honored by such names as ‘the Dustbin.’ I again saw Keitel at the Nuremberg Trials when I was in the audience. Keitel, whom I would estimate to have been 6 foot 4 inches, and weighing 250 pounds, looked visibly diminished both in size and importance in the court of war criminals.”

John Brunswick

XV Corps, Third Army, Bocholt, Germany

“Due to heavy German resistance that slowed our advance, we stayed for about two weeks in a little town in France named Gerbéviller, but we were kept very busy at times with the German prisoners brought to our HQ for interrogation. Then one day something strange happened. I sat on one side of a table together with one of our men and a prisoner was brought into the room.

“Before interrogating him, he had to empty his pockets and show his German Army papers, which gave his name and serial number. This man was Martin Look, who said he was born in Bocholt. I had gone to school with Martin Look for four years, from age six to 10, and had even been in his parents’ house.

“Now I met him again, about 25 years later, and didn’t recognize him. I doubted that he recognized me, and he was certainly not in a position to ask an American officer any questions, but for half a minute I was tempted to ask him if he still had the wood-burning stove in his family’s kitchen.

“Then I decided that not only did I not know whether or not he’d been a Nazi Party member, but that I also did not want any gossip among other POWs, so I sent him on his way, just like everyone else. I later found out from my old neighbors in Bocholt that Martin Look had told somebody that ‘Hans Braunschweig was the American officer who interrogated me.’ I still regret not having revealed myself during the interrogation.

“Another interrogation that I remember vividly took place under more quiet conditions sometime earlier in the fall of 1944. The man I interrogated seemed intelligent and reliable. He was with what might be best translated as a punishment company. After he gave me all the information I wanted, like armaments, officers, and opposing regiments, I asked him why he was in a punishment outfit.

“He said, ‘I was on the Eastern Front near Riga, Latvia, where the SS rounded up thousands of Jewish men, women, and children. They made the Jews dig ditches, undress, and stand so that, when they were shot, they would fall into the ditches. This went on every day. There were so many that the SS needed help and requested regular army troops to help kill the Jews. I refused and that is why I’m in the punishment battalion.’

“While I had heard rumors of concentration camps, being cut off from all current news, mass murders surpassed anything I had imagined. I forwarded my interrogation report immediately to the division and also directly to Corps Headquarters, where I hoped it would be going up to higher headquarters. I have a copy of this interrogation still in my files because I was so shocked, even though this was against all Army orders.

“We captured Julius Streicher. He had been a particularly sadistic anti-Semite. His newspaper Der Stürmer showed the most vicious caricatures of Jews, said the most outrageous lies about Jews, and incited the people to violence against them. The paper was read all over Germany and Austria. The man himself used to strut around with a horse whip in his hand. At any rate, he was jailed and I interrogated him in his cell before he was shipped back for more detailed questioning over many days.

“I was amazed to hear that he was actually a friend of the Jews and, like the Zionists, just wanted them to go to Palestine. I questioned, listened to his answers in amazement, and took notes. He sounded so ridiculous and pathetic that I could not even hate him. He was sentenced to death as a war criminal during the Nuremberg Trials and eventually hanged.

“I received orders to report early on May 5 to headquarters of the XV Corps, right outside Munich. Subsequently, I found out that I had been selected to be the official interpreter at the surrender of all the southern German armies. The German General Friedrich Foertsch was the chief of staff of General Albert Kesselring, who was the commander of all German armies that had been in Italy, Austria, and southern Germany. There were six American generals, including General Jake Devers, who was the commander of the two American armies in the southern part of France and Germany. Then there was also one lowly 1st Lt. Brunswick.

“There were long negotiations with the Germans—the officers wanted to stay in charge of the troops, they wanted to keep their side arms, and so on—all to no avail. Finally, this Jewish refugee who, eight years earlier had to leave his homeland, asked this high-ranking German general: ‘Do you understand that this means unconditional surrender?’ To this, with utmost reluctance, the general eventually spat out, ‘Yes, I understand.’ In any case, it was a moment in my life that I will relish as long as I live.”

John Stern

397th Infantry Regiment, 100th Infantry Division, Gilserberg, Germany

“The 397th Infantry became part of the army of occupation in the Stuttgart and surrounding area for several months. We had been on the line 192 days, with small breaks in between.

“While in the Stuttgart area, I was able to requisition a jeep, and a Polish lieutenant from the labor supervision company [a Polish company] went with me for protection while I visited my birthplace, Marburg on the River Lahn. I also went to Battenberg, my mother’s birthplace, and Gilserberg, where my parents lived before moving to Frankfurt.

“In Gilserberg, I met some of my earlier acquaintances who went to school with me before 1933 and it was interesting because quite a few people welcomed me. My grandfather’s name was Gutkind—they used to call me Gutkind’s Hans.

“It was clear that they were astounded that I was an American soldier and back there. Some woman said, ‘You never looked like a Jew. You were always so nice.’ All of the others were stoic. They thought we were going to take all of their property back.

“I looked for family in Marburg. Nobody wanted to tell me anything. We know an uncle, aunt, cousin, and a baby cousin were transported to Theresienstadt and ultimately perished there. During the Holocaust, the Stern family lost 26 close and distant relatives. This, in itself, dampened my spirit at homecoming.

“The captain and lieutenant of our unit had arranged that I act as an interpreter when questioning of German officials, such as mayors of towns, police chiefs, and German military people, took place. I interpreted for several months.

“Whenever the burgermeisters [mayors] were pulled into the headquarters and asked a lot of questions, I was involved. In most places, the Germans had innumerable requests for cigarettes and cigars, but I wouldn’t give them any.”

Karl Goldsmith

142nd IPW Team, U.S. Army, Eschweige, Germany

“When the war finished, I immediately put in a request to be involved with the de-Nazification of my hometown. I wanted to do that so badly. They kicked the shit out of me so much as a kid.

“I had earned some brownie points with a whole bunch of big-shot officers because I had done them favors in my team’s capacity as interpreters and interrogators. I got the transfer, and as far as I know, I was the only one of the interrogators who ever succeeded doing that.

“The first thing I was concerned about was getting the damned Nazi teachers out of the schools. I worked bitterly hard to get things straightened out.

“This was my town, Eschweige—the gardens, woods, trails, hills, friends, enemies, Bar Mitzvahs, parties, frightful beatings, Nazi torch parades, Kristallnacht, and the end of the town’s Jewish population in 1942 after more than 600 years of settlement.

“As the military governor, I really think I was a pragmatist. I believed in law and order, and I was a presence in that town. Yes, I found the Nazi perpetrators and they wound up in jail. Aside from that, we cleaned the town up. Everyone knew me, and naturally people came and asked me for this and that—and I did nothing. I wasn’t going to treat this one better than that one. Old acquaintances would come to me and say things like, ‘Oh, you remember Analee?’ Of course, I remembered Analee––she lived four houses away from us. ‘Well, she’s expecting a baby anytime and she is in a third floor walkup. Can you help us?’

“My answer was always: ‘I’m sorry, I cannot do anything about it.’ What was I supposed to do, inconvenience one miserable German for another miserable German? I was flabbergasted that these people had the temerity to face me and say these things to me, when they knew what they themselves had done to me and my family. Forget about all the other people who got burnt up in concentration camps.

“One of the old neighbors called me Der Ungerkronte König, the ‘uncrowned king.’ I lived well and had a great social life. I doubt if my father would have approved, but I did not compromise or bring dishonor on my adopted country or family.

“About two years later, after I’d come back to America, my mother had gone to Eschwege to take care of our properties there. When she came back, she said, ‘Karl, you can never go back to Eschwege; they’ll kill you.’”

Manfred Gans

3 Troop, 10 Commando, British Army, Borken, Germany

“I was absolutely set on seeing the war through and making sure that I was there to see Germany liberated from the Nazi government. Very often, I thought about what might have happened to my parents and occasionally I got very depressed.

“In the fall of 1944, I heard from my uncle in New York that he had received word from a family friend in Switzerland who had heard that my parents were rumored to be alive in Theresienstadt concentration camp. Well, as far as I was concerned, the war was over on May 7, and I persuaded my unit to let me go, give me a jeep and a driver, and go find my parents.

“Being in Germany, I tried to go through territory that was known to me. Essentially, I tried to hit the eastward autobahn as soon as I could. I wasn’t really scared; I was more worried about the brakes on the jeep than about getting behind enemy lines. When my driver and I reached Aue, the town was undamaged and had not been looted. German police and thousands of German soldiers were on the street. Two and half German divisions had yet to surrender and were still intact. We passed a lot of positions that were still completely manned. There were roadblocks with perfectly good antitank guns guarding them, but no one went behind their guns or put their finger on their triggers. They actually let us through. Nobody had expected us.

“Soon I picked up a wounded German soldier and his girlfriend because I felt safer having people like them in the jeep. All of the Germans who I encountered broached the subject of whether they could surrender to me and I said, ‘No, you can’t. You are fighting the Russians and you’ll surrender to them.’

“A German woman said, ‘You know, the Russians will rape everybody, they’re so cruel. How can you do this to us?’

“In a snappy reply, I said, ‘This is what you people did in Russia and Poland, too. You were very cruel.’

“Their reaction to that was, ‘There are bad people among all nations.’

“I remember thinking, ‘What the hell am I saying here amongst the last two divisions of the German Army who have yet to officially surrender?’ Imagine me accusing them of being cruel to Eastern Europe!

“When we got down from the mountains into Czech territory, we ran into the Russian Army. That was a great experience. They were so happy to see us! You would not believe their enthusiasm—they had seen American and British liberated prisoners, but they had never met an officer in a vehicle who had weapons before, and they were beside themselves with joy. Most of the MPs directing the traffic were women, and they all embraced us. In fact, they practically raped us.

“When we reached the Russians, I still had another hundred miles to go, but we were making good time. The Russian Army was coming in the opposite direction, but there was no heavy traffic. We continued to make good time, driving about a hundred miles in two and a half hours. Toward evening, we managed to get to Theresienstadt.

“The camp was behind heavy barbed wire, with Russian guards outside. I walked up to the Russian guards at the gate, and once again everybody was delighted to see us. After all of the handshaking, congratulating, slapping each other on the back, and saying how happy we were to meet each other, I told him what I wanted. The beam went up and we drove into the camp. There were a massive number of people in there, all terribly crowded; most were too weak to get out of the way. People were practically crawling through our legs.

“I did not know where to start looking. Somebody drew my attention to the fact that there was a central register, so I made my way there. The camp, having just been in German hands, was of course very organized as far as lists and things like that went.

“There was a girl there who spoke English, and I told her that I was looking for my parents, Moritz and Else Gans. There was an endless list. After a few moments, she looked up and said, ‘You’re lucky, they’re still here. They are alive.’

“I said to her, ‘Well, there’s no two ways about it. You’re going to show me, and you’re going to take me to them now.’

“She came with us on the jeep and took us to the house where my parents were registered to live. My parents were living on the second floor of a house in the Dutch section of the ghetto. I told the girl to go upstairs and tell them that their son was there, but to prepare them a little bit for it first. I just waited outside.

“She went inside and told them, ‘I have a very joyous message for you.’

“My mother asked, ‘Are we getting some extra food?’

“The girl said, ‘No, your son is here.’

“I stood outside in the dark and, after maybe a minute, my parents came out. Of course, they were in an unbelievable state. My father was so decimated, if I had met him on the street, I would not have recognized him.”

Kurt Klein

5th Infantry Division, Walldorf, Germany

“Once we reached the border of Germany and Czechoslovakia, I happened to have what I call my ‘rendezvous with destiny.’ We came across a group of what had been slave laborers, young Jewish women from Poland and Hungary. They had been abandoned by their SS guards in the town whose surrender we had taken just days before the end of the war. We had heard about them and knew we had to go there reinforced by our medical battalion and render some aid.

“Once I walked into the factory where the SS had locked them up, I met a young woman who was standing at the entrance and who took me inside when I asked her. She left quite an impression on me. She was at the end of her strength and collapsed once. Our medics took them all to the field hospital that we found in town. Out of that encounter evolved a friendship with a person of rare caliber, which developed further and one year later we were married in Paris.

“Now this makes me reflect on the fact that I had gone to Europe to fight the Nazis with hatred in my heart for all they had inflicted so gratuitously on Jews and the world. I had to witness the results of what they had done to my people. Also, I was 95 percent sure that my parents could not have survived the war. While all of that was true, for me personally it was the key to my own future.”

Most of the refugees who went back to fight against the Nazis and liberate the lands of their birth did so with courage and conviction, some even dying in the process. After the war, many built new and successful lives in America, becoming physicians, architects, chief executives of international corporations, small business owners, Wall Street scions, economists, attorneys, educators, inventors, entertainers, writers, public servants, and simply productive and hardworking citizens.

Kurt Klein spoke for many of the others: “I felt proud that I could serve the United States in the capacity that I did. Nothing made me happier than being of some use to America after what it had given me, which was the idea that I could live in freedom. I live with the regret that my parents could not make it out, otherwise my happiness could have been

complete.”

This article is adapted from Steven Karras’s book, The Enemy I Knew (Zenith, 2009).

Incredible men at an incredible place and time.

I hope they were able to eventually make peace with the world.