By M.G. Haynes

Korean General Kwon Yul shouted the one-word order down the hill. Scarcely had it left his lips before it was lost in a deafening crash. Haengju Fortress seemed to erupt in flames as thousands of rocket-propelled arrows arced high over the ramparts and plunged into the densely packed Japanese samurai ranks below. The explosive and unexpected volley caused indescribable carnage and chaos amongst the attacking force.

After the eruption of arrows, the Japanese pulled back in confusion to a safe distance before launching further assaults against the ancient fort. But each successive wave was welcomed in turn by a storm of iron-tipped, exploding arrows.

Twelve hours later, with the Japanese burning their dead and commencing a sullen withdrawal back to the safety of Seoul’s high city walls, Kwon Yul no doubt smiled for the first time all day. Commander of a rag-tag army of 2,300 soldiers, guerrillas, monks, and local townspeople of every background and description, his motley force had miraculously withstood nine separate assaults by a veteran enemy army that outnumbered them thirteen-to-one. The narrow victory had been made possible only by his corps of artillerymen manning Joseon Korea’s secret weapon.

The defense of Haengju on March 14, 1593, during the Imjin War (1592-98) remains a significant event etched in Korean history. The so-called Imjin War was in reality two invasions, in 1592 and 1597, that were launched by the powerful feudal lord (daimyō)Toyotomi Hideyoshi with the intent of conquering the Korean Peninsula, ruled by the Joseon dynasty and China, ruled by the Ming dynasties. Initially, Japan was able to occupy much of the Korean Peninsula. But the position became untenable as reinforcements came from China and the Joseon Navy disrupted Japanese supply fleets along the southern and western coasts. Guerrilla resistance and supply problems brought the conflict to a stalemate. After the death of Hideyoshi in 1598, Japanese forces withdrew from the Korean Peninsula.

The Haengju Fortress, a wooden stockade perched on a cliff overlooking the Han River was a strategic location that posed a threat to Hanseong (modern-day Seoul), prompting the Japanese forces there to launch an attack.

On that fateful day, a formidable Japanese army of 30,000 men, led by Konishi Yukinaga, commander of the Japanese First Contingent, marched upon Haengju. With such a large force, the Japanese apparently felt their usual dispatch of scouts wasn’t necessary before attacking the outdated fort. It seems they hadn’t realized, until arriving on the scene, just how narrow the approach really was. The limited space around the stockade forced them to take turns assaulting it. Undaunted, they arranged themselves in multiple lines, with battle-hardened veterans leading the way. The Korean defenders fought back fiercely, using a combination of arrows, cannons, and the hwacha to repel the invaders.

Despite three attacks, including one with a siege tower, the Japanese struggled to breach the outer defenses. During the intense fighting, Ishida Mitsunari was wounded, and Ukita Hideie (son-in-law of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the Retired Regent of Japan who had launched the invasion of Korea) managed to breach the outer wall but was also wounded and forced to retreat. In a final desperate attempt, Kobayakawa Takakage, commander of the Japanese Sixth Contingent, burned a hole through the fort’s log pilings, but the Koreans held their ground until dusk. Just when they were nearly out of arrows, supply ships containing 10,000 more arrows arrived, allowing them to continue the fight. Ultimately, the Japanese were forced to retreat.

The limited space had meant that the Japanese assaults were distinct and came at intervals—during which the hwachas were probably reloaded, much to the dismay of the attacking samurai. Following a Japanese breakthrough of the lower barrier, and subsequent flood of invaders into the fortress, the tactical situation wouldn’t have allowed for such clean engagement of successive assault waves. Yet the breach had been narrow and so the large attacking force would have stacked up outside for quite some distance, providing a tempting target for the garrison’s hwacha crews. These men—knowing full well the value their weapons brought to that fight—undoubtedly worked as rapidly as they could, with officers nervously eyeing both the desperate melee below and the progress of reloading.

In addition to being one of Korea’s most famous conflicts, the Battle of Haengju represented the best conditions imaginable for the employment of the simple but effective hwacha.

In 2024 the world stands in awe of the power of multiple rocket launchers and their use in combat. The provision of the High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) to the army of Ukraine has been a major contributing factor to the success that force has seen defending their country against Russian invasion. Yet the developmental ancestry of such a potent weapon system has a surprising lineage. One that includes an ancestor from the far-off, misty peaks of medieval Korea, at the time called the Kingdom of Joseon.

Gunpowder was invented in China in the 9th century CE, with its first documented military use in 1044 as a method of igniting containers filled with Greek Fire. Continued development produced fire lances—essentially a roman candle attached below a spearhead—and even “fire tubes” which dropped the lance altogether, leaving a spark-shooting bamboo tube. Historians have sometimes wondered if the first rocket was accidentally “invented” as the result of a dropped fire lance, the weapon rapidly accelerating rearward once free from a soldier’s grip.

Regardless of its precise origin, by the 12th century, exploding projectiles hurled by catapults or fired from oversized crossbows had become commonplace throughout the region. By the 14th century, cannons and true rockets were growing in popularity across the Far East. Yet initial attempts at building rockets for military use were hampered by dangerous and unpredictable inaccuracy. A weapon that can’t be aimed is virtually useless, after all.

Turning to an age-old solution, weapons developers attached small tubes of gunpowder to arrows loosed from the ubiquitous Korean recurve bow. The fletching of the arrows solved the accuracy problem and the gunpowder-filled tubes increased both range and penetrating power. It was only a matter of time, then, until Chinese and Korean craftsmen would realize the full potential of these projectiles and construct ever more effective weapon systems to employ them.

Created in 1409 during the Joseon Dynasty by several Korean scientists, including Yi Do and Choi Hae-san, the projectile that made more sophisticated weaponry possible, the singijeon, (“magical machine arrows’) was perfected in 1448. The singijeon was an arrow with a tube of gunpowder attached in addition to a small explosive charge which detonated at the conclusion of flight. Singijeon were created in three variations, essentially small, medium, and large. The largest variety was reportedly capable of an amazing 1,000 meters in range, a phenomenal reach in the 15th century.

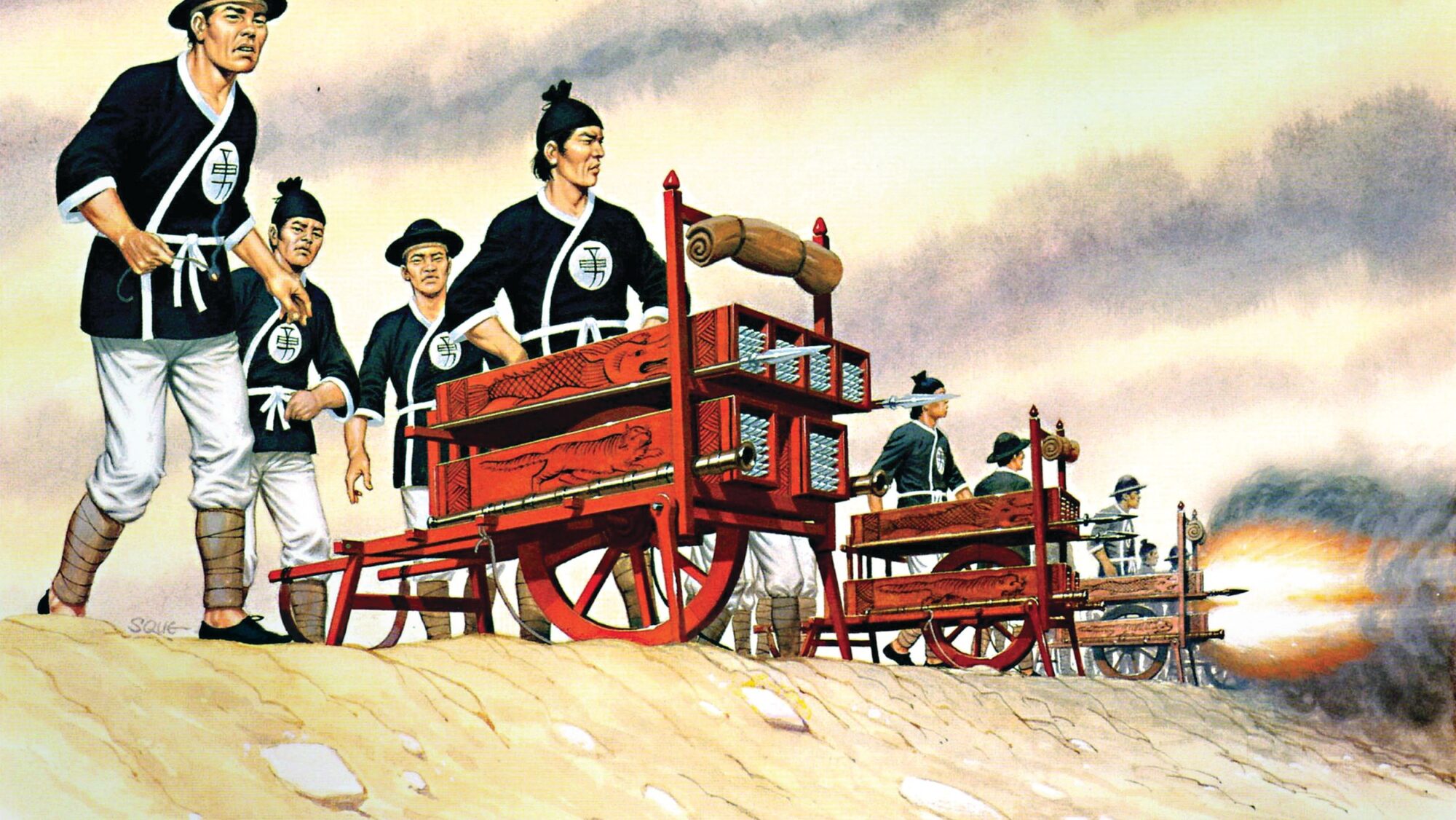

In 1451, the combination of accurate, rapid firing rocketry and the easy maneuverability provided by a simple hand cart, produced the first hwacha. The hwacha was, essentially, a rack of rocket arrows attached to the top of a two-wheeled cart. By the time of the Imjin War (1592-98) this weapon system came in one of two variants. The wooden rack either had holes drilled through it in order to launch the small type singijeon, or held 50 small, permanently mounted, bronze gun barrels, much like later European organ guns. In either case, the fuses were all linked together to provide a single fusillade.

The gun barrel version—with each barrel propelling four small, iron-tipped bolts, would have had the effect of a modern claymore mine, blasting 200 darts at a target with each discharge. With the singijeon version, 100 rocket arrows were delivered in a manner very similar to the firing of a Soviet Katyusha Rocket Launcher during WWII.

Fired as an artillery piece more than the direct-fire rocket wheelbarrows built and employed by Ming China, the hwacha delivered a single, massive volley out to about 450 meters, reduced to 100 in bad weather according to observers at the time. Devastating in its effect upon a closely packed body of enemy troops, the weapon system would have been time consuming to reload, meaning that any decision to fire required serious consideration and, at times, nerves of steel.

The fluid nature of Imjin War combat to date meant neither type of hwacha had ever before been used en masse prior to the defense of Haengju Fortress. The firepower generated by 20 such pieces, positioned on the heights above them, must have been a shocking development to a Japanese army expecting to clear out a small, if troublesome, guerrilla force.

The hwacha would be specifically called out for its effectiveness that day, successfully defending Haengju against all odds. It was singled out for praise at other points during the Imjin War as well—following both sieges of Jinju City and then later, mounted on naval vessels, after the failed attack on Suncheon Castle and subsequent final battle of Noryang in 1598.

These noteworthy moments aside, the hwacha made its presence felt in most defensive sieges throughout the war, as well as a few assaults on Japanese strongholds, though the long reload time limited its utility in the attack.

Along with the Battle of Haengju, the first battle of Jinju, are regarded as two of the most important battles of the war.

At Jinju in November of 1592, a detachment of 15,750 soldiers from the Seventh Japanese division advanced on the city which was defended by 3,800 soldiers, with cannon, hwacha and a small number of arquebuses—early muzzle-loaded matchlock firearms.

The Koreans held out for six days before the arrival of the main leaders of the Righteous armies of Korea, Gwak Jae-u, with a small group of men. Gwak had the men blow horns, which attracted about 3,000 guerrillas and irregular forces to the scene, alarming the Japanese commanders, who thought they were surrounded by a relieving force.

In July of 1593, the Japanese returned and burned Jinju to the ground, slaying nearly all the inhabitants except for some concubines.

One of these women would become a legend. During the Japanese victory celebration after the battle, Nongae, concubine to an assassinated provincial official, is said to have danced for a Japanese officer near the cliff overlooking the river—she then embraced him and dove off the cliff, killing them both. A shrine still exists near the spot to honor her sacrifice and willingness to resist even after the city had been lost.

Uncomplicated in the extreme, the hwacha was, in reality, little more than a commonsense pairing of existing technologies to create something both new and decisive. Over the course of six long, bloody years of fighting, the hwacha contributed significantly to Korea’s struggle to evict the Japanese invaders. Odd as it may seem, then, the employment in battle of a modified handcart might be said to have preserved an entire kingdom.

Nevertheless, the hwacha represented the ground component to an advantage in artillery already maintained by Joseon’s navy over the Japanese invaders. This, at times, helped balance out the otherwise terrible disparity in hand-held firearms which remained a distinct Japanese advantage throughout the conflict. To further emphasize this fact, during the lull in ground combat from 1593 to 1597, Joseon’s armories specifically prioritized increased production of two weapon systems: cannon for warships, and rocket-launching hwachas, subtle, if concrete, testimony to the regard with which the weapon was held.

The hwacha’s deployment was one of the key factors that led to Japan’s failure in their campaign to conquer the Korean peninsula. Simple in design, brutal in employment, ghastly in its effect upon the enemy, the hwacha proved to be a war-winning weapon for Joseon, greatly contributing to the ultimate—if hard-fought—Korean victory in 1598.

Today, hwachas can be seen in Korean museums, national parks, and popular culture, serving as a testament to Korea’s innovative military technology during the Joseon Dynasty. The victory at Haengju was important psychologically, for it gave the populace a feeling of hope, a sense that Japanese aggression would recede after all. Four centuries later, “Haengju Skirts,” a type of kitchen apron that women within the fortress used to carry rocks to the ramparts, are still produced and worn.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments