By Tim Miller

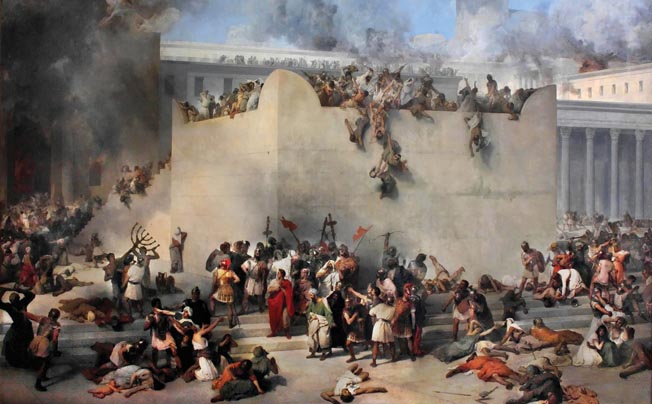

After a summer of starvation and siege had been imposed on the city’s people during the fall of Jerusalem, the great Second Temple was finally on fire. No one knows who threw the flaming brand, or indeed how the temple had avoided such a fate for so long, but once the conflagration began there was no stopping it.

The Jewish soldiers, outnumbered and hungry and armed only with weapons they had won from the Romans in battle, immediately refocused the physical courage and fanaticism that had helped them hold out for so long. The earthly embodiment of their ideals was now being destroyed, and their own freedom from Roman rule and even their own lives were nothing now that the Temple faced destruction. (Read more about the war-torn history of Jerusalem and the ancient battles that defined world history inside the pages of Military Heritage magazine.)

“As the flames shot into the air the Jews sent up a cry that matched the calamity and dashed to the rescue, with no thought now of saving their lives or husbanding their strength; for that which they had guarded so devotedly was disappearing before their eyes,” wrote the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus.

When Titus, son of the new emperor Vespasian and the Roman general in charge of the siege, heard the news he raced to the scene and demanded that the fire be put out. The Roman army either pretended not to hear, or simply disobeyed, throwing more wood on the fire. “Everywhere was slaughter and flight,” wrote Josephus. “Most of the victims were peaceful citizens, weak and unarmed.” As the Roman legionnaires pressed their advantage, the pile of corpses surrounding the alter grew ever higher.

There was as much use arguing with the Roman troops as there was with the fire itself, according to Josephus. After some of the most brutal fighting in Roman history, and after a seemingly endless round of Roman victories and Jewish resurgence, the fire and bloodletting at the Temple was a total and terrible release. “[The soldiers’] respect for Titus and their fear of the centurion’s staff were powerless against their fury, their detestation of the Jews, and an uncontrollable lust for battle,” he wrote.

The huge white marble Temple complex, which gleamed with such a luster that it might be compared to a mountain covered in snow, and the city choking with civilians and insurgents and Romans, all swirled and culminated in a butchered, bloody, and smoky end on September 8, ad 70.

Jewish and Roman relations had never been great. Following his siege of the city in 63 bc, the Roman general Pompey the Great had profaned the Temple by entering the Holy of Holies, which no one but the High Priest was allowed to do, and that only once a year, merely to survey its riches. Following more than two centuries of Hellenistic rule, during which nearly every aspect of Greek life, not to mention paganism, was found offensive to the Jews, the Romans took over. They were equally offensive in the eyes of the Jews.

Pompey the Great had intervened militarily in the affairs of Judea in 63 bc. From that point forward, Judea became a client kingdom of the Roman Republic. Rome officially annexed Judea as a province in ad 6. Opposition to Roman rule was immediate. The sicarii, or knife men, were assassins who conducted hit and run attacks and then hid in the desert from Roman patrols trying to apprehend or kill them.

If the old cliché about the Romans is true, that they were merely brutes who elevated themselves by appropriating a good deal of Greek culture, their inability to rule in Judea is easily understood. Bureaucracy, organization, and a show of strength should have been enough to subdue a minority culture not known for its military might, but it was their religion that was the source of their seeming stubbornness. Not even Rome’s eventual victory would snuff out Judaism.

In Judea there also were locals who were willing to work with the Romans as far as they could, no matter how incurious, ignorant, or ineffective their foreign overlords proved to be. But it did not take long for such Jews to lose favor with the larger community. The weakening of any aspect of Jewish ritual or legal life was viewed with suspicion, and almost immediately the Jewish population disintegrated into a handful of competing allegiances. The Jews harmed themselves by this infighting more than the Romans ever could.

In what essentially boiled down to class warfare, the words of Josephus are strikingly modern. He noted that those in power oppressed the masses, and that “the masses [were] eager to destroy the powerful.” To the oppressed masses, who supported the more popular fundamentalism of the Pharisees, the great enemies were the Temple elites and the largest landowners, the Sadducees. There also were the ascetic and apocalyptic Essenes, but they lived away from the city and considered Temple life irredeemably corrupt. Added to this, Roman influence in the area was perpetually mediocre and easily undermined because the area was not of much interest in the wider Roman world. Of the quarter million men who made up the Roman standing army, only 3,000 were stationed in Judea at the beginning of ad 66.

In the last decades before Christ and those following Herod the Great’s death, while there was the occasional upheaval in the province, there was little that could be deemed anti-Roman, and none of which could be said to presage the destruction of the late 60s. The Roman historian Tacitus simply says “all was quiet” in reference to Judea during the years of the Emperor Tiberius from ad 14 to 37. But that began to sour in ad 40 when Emperor Caligula departed from the policy of religious tolerance exercised by his predecessors. The chain of events over the next 26 years ultimately led to the ascendency of the Zealot party.

Deeming Judea a province of no military significance, the Romans entrusted its rule to a governor of procuratorial rank. Many of the governors of Judea during this period were corrupt. Added to this, the governors tended to overreact to disorder and suppress it with heavy force.

Caligula’s Discontent

Caligula stoked the flames of discontent as well. He demanded that a statue of himself be placed for worship in the Temple at Jerusalem. Publius Petronius, the Roman governor of Syria, traveled to Jerusalem to quell the unrest. He asked the Jews if they were willing to go to war with Caligula over the matter.

“The Jews replied that they offered sacrifice twice daily for [Caligula] and the Roman people, but that if he wished to set up these statues, he must first sacrifice the entire Jewish nation; and that they presented themselves, their wives and their children, ready for the slaughter,” wrote Josephus. Caligula was murdered in the interim and the matter was dropped. The response of the Jews was ample proof that they were willing to sacrifice themselves rather than dishonor their God.

As it happened, the events that led to the rise to prominence of the Zealots and their subsequent revolt can be traced to an avoidable miscalculation by the inept procurator Gessius Florus. In May ad 66, a Gentile mob had profaned a synagogue in Caesarea, a town on the Mediterranean coast 78 miles northwest of Jerusalem. A Greek, who was aware of the strict laws held by the Jews in regard to ritual purity and cleanliness, “placed a chamber pot upside down at the entrance [to the synagogue] and was sacrificing birds on it,” wrote Josephus. Similar provocations had taken place in the previous decade; for example, Roman soldiers had exposed their buttocks to Jewish pilgrims. They also had seized and burned sacred Jewish scrolls.

This time the events in Caesarea would spiral beyond anything that had come before. Matters pertaining to local government and religion in Jerusalem were the purview of the High Priest and his council, the Sanhedrin. When the Jews of the area began to complain, Florus ignored their pleas.

Florus decided it was a good time to collect overdue taxes. His demands were met with anger in Jerusalem. Some youths went so far as to mock him by roaming the streets with a basket, begging for pennies for the seemingly impoverished governor. Florus demanded that the offending youths be handed over for punishment. The Sanhedrin authorities apologized for the behavior of the youths, but they refused to turn them over, saying it was impossible to identify the guilty parties in such a large crowd.

In a clear example of the brutal repression in Judea exercised by the Romans, Florus ordered his soldiers to the southwest market area of the city with instructions to slay indiscriminately those they encountered. “There followed a flight through the narrow streets, the slaughter of those who were caught, and rapine in all its horror,” he wrote. “Many peaceful citizens were seized and taken before Florus, who had them scourged and then crucified.”

Almost immediately, Jewish radicals calling for revolution took control of the Temple. They suspended the daily sacrifice for the well-being of the Roman emperor and the people of Rome. Refusal to carry out the daily sacrifice was an overt act of rebellion as far as the Romans were concerned. The radicals also ordered the burning of many of the homes of the rich, including that of puppet king Herod Agrippa II. The radicals also destroyed the public archives, which brought many of the rural poor over to the revolutionary side. The conservative faction, meanwhile, fled to Agrippa’s palace, along with the 500 auxiliaries Florus had left in the city before leaving himself.

When the Roman auxiliaries decided to sue for peace, the rebels assured them of their safety. Once they were marched out and relieved of their weapons, the rebels “fell upon them, surrounded and massacred them; the Romans neither resisting nor suing for mercy, but merely appealing with loud cries to ‘the agreements’ and ‘the oaths,’” wrote Josephus. To the people of Jerusalem, war with Rome seemed inevitable at that point, as did a sense of their own collective guilt and ritual pollution. The city gave itself up to public mourning for what the future would bring, while those in the conservative faction quaked with fear as they contemplated the suffering that would be inflicted on them for the rebels’ crimes.

Despite the fracture among the Jewish authorities and the terrible violence the rebels had already given to the Romans in reprisal, a wider war could have been avoided. Cestius Gallus, the Roman governor of Syria, was called in to quell the disturbances. He initially tried to resolve the matter with diplomacy by sending his tribune Neapolitanus to Jerusalem. Neapolitanus and Agrippa tried to quiet the unrest but were unsuccessful.

Gallus marched from Antioch to Palestine with a large army, the core of which was the XII Legion. On his way to Jerusalem he left a path of destruction along the seacoast in his wake, burning villages and slaughtering their inhabitants. Before he reached Jerusalem, Agrippa delivered to the rebels a peace treaty on behalf of Gallus. It included a general pardon for the rebels, on the condition that they disarm. Perhaps with their own butchery of the unarmed Roman auxiliaries in mind, the offer was refused and one of the emissaries was killed for even bringing it.

In response, Gallus continued to Jerusalem. He fought his way into the city through the northeast suburbs where he encamped for five days before the second wall near Herod’s Palace. The approach of winter with its heavy rains, as well as raids on his supply line, compelled Gallus to withdraw through Palestine. “Had he, at that moment, decided to force his way through the walls he would have captured the city forthwith, and the war would have been over,” wrote Josephus.

The Jews harassed his retreat, forcing him to discard valuable war materials to speed his withdrawal. His best troops, whom he had left as a rear guard, were cut down at Beth Horon Pass. Gallus lost 5,000 men, 500 cavalry, and his siege and baggage trains during his withdrawal. The Jews also captured a legionary standard. The Jews’ success gained siege artillery they lacked and also boosted their confidence. The heavy losses inflicted on Gallus’s army guaranteed that the Romans would respond with even greater force.

In-Fighting within the City

The Romans did not launch another major offensive against Jerusalem for four years. Meanwhile, the city seethed with turmoil. The Romans were willing to watch the factions under various warlords fight among themselves.

Rome gave the job of suppressing the Jewish revolt to 58-year-old Vespasian. His family belonged to the equites, the second of the property-based classes of Rome ranking beneath the senatorial class. His uncle had served as a senator, and then as praetor, but that was as distinguished as his pedigree got. Although not in favor at court at the time of his appointment, Vespasian seemed right for the job because his relatively obscure origins ensured that if he were entrusted with a sizable command he would not have grandiose plans to use the army to press his own gains. Vespasian had a long record of military service.

While serving as legate of Legio II Augusta during the final conquest of Britain in ad 43 he compiled a distinguished combat record that earned him triumphal regalia. He went on to serve in Africa and held the consulship in ad 51 during the reign of Emperor Claudius. As a member of Nero’s retinue traveling in Greece in ad 66, he was nearly executed for falling asleep in ad 66 during one of the emperor’s interminable musical performances. Quite literally fearing for his life, Vespasian had gone into hiding rather than face Nero’s fickle and whimsical reprisals. To quash the rebellion in Judea, he was given the title of propraetorian legate with command over four legions.

Vespasian opened his campaign in April ad 67 with a campaign in Galilee. The commander of the Jewish defenses in Galilee was none other than Josephus. After a successful 47-day siege of Josephus’s army at Jotapata, Vespasian took Josephus prisoner. In his work, Jewish War,which Josephus wrote in the decade following the conflict, he provides a detailed account of the struggle. Josephus was an ideal chronicler given that his family had been active in political life before First Jewish-Roman War, also known as the Great Revolt. After his capture, Josephus recorded events from both sides given that he witnessed the rest of the campaign from the Roman camp.

An aristocrat, priest, and Pharisee by education, Josephus claims to have considered suicide over capture, but a dream from God convinced him that he should remain alive and that the fall of Jerusalem was inevitable. He also prophesied that Vespasian would one day become emperor, a claim that at the time must have seemed far fetched. This was a year before the turbulent period known as the Year of the Four Emperors in which Rome would go through a string of emperors following the death of Nero on June 9, ad 68, before stability was restored.

Eccentric, narcissistic, and perhaps even psychopathic, the end had finally come for Nero. He had already forced numerous aristocrats and scholars, among them Seneca, to commit suicide for their roles in real or imagined conspiracies against him. While only 30 years old in ad 68, he had spent nearly half his life as emperor, using his position and authority mostly to fulfill the usual tabloid desires and pursue a career on the stage. In the spring of ad 68, Gaius Julius Vindex, the governor of Gallia Lugdunensis, declared himself emperor. While this revolt was being put down, Sulpicius Galba, the governor of Hispania Tarraconensis on the Iberian Peninsula, also revolted. He decided to march immediately on Rome while Nero was still alive. Galba was assassinated, and Otho (Marcus Otho Caesar Augustus) committed suicide following his defeat at the First Battle of Bedriacum on April 14, ad 69, against the forces of Aulus Vitellius, commander of the army of Germania Inferior. Two days later Vitellius became emperor.

Meanwhile, Vespasian had stamped out rebel activity in Judea except for Jerusalem, secured his supply lines, and begun to his advance on Jerusalem. Nothing short of a miracle could save Jerusalem. The miracle came in the form of chaos in Rome. Abandoning Jerusalem, Vespasian travelled to Alexandria, Egypt, where he declared himself emperor. Egypt’s prefect and legions approved, and so did his troops.

Vespasian’s legions in Syria marched west through the Balkans and defeated Vitellius’s legions at the Second Battle of Bedriacum on October 24. Afterward, the legions of Britain and Spain declared their allegiance to Vespasian. Upon arriving in Rome, Vespasian’s men hunted down and executed Vitellius in the forum. They then threw his body in the Tiber River. At that point, Vespasian sailed from Alexandria for Rome.

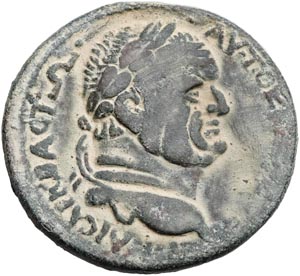

With little in his background to justify his position as emperor and having no direct hand in vanquishing Vittelius, Vespasian desperately needed a victory against the Zealots of Jerusalem. Vespasian entrusted command of the campaign to his son Titus, who marched against the city in April ad 70. With political and logistical stability in place, Titus wasted no time moving on Jerusalem. With previously only a small force to hold Judea, Titus was given four legions totaling 60,000 troops. His army consisted of the Legio V Macedonia, Legio X Fretensis, Legio XII Fulminata, and Legio XV Apollinaris. The army was supported by a force of 16,000 noncombatants responsible for supply and logistics.

The Jews had nothing comparable to Titus’s professional army. By the time the siege began, several rebel leaders had come to the forefront. These were John of Gischala, Simon Bar Giora, and Eleazar ben Simon.

John was “the most cunning and unscrupulous of all men who have ever gained notoriety by evil means,” according to Josephus. Reality seems much more prosaic. He was at first against the rebels, but he quickly changed sides when the Romans allowed the Greeks from nearby Tyre to sack Gischala. He then briefly fought with Josephus, eventually winding up in Jerusalem as another fighter for another faction.

Simon had been a part of the rebellion from the beginning, having led the Jewish forces that ambushed the Romans at Beth Horon Pass. In the intervening years, he briefly fell out of favor in the city and retreated with his men to the mountain fortress at Masada. He was called back later to restore order and he didn’t relinquish power again until the Romans captured him.

As for Eleazar, he was a renowned Jewish chieftan who had fought with distinction against the Roman garrisons in Judea.

The Fall of Jerusalem: Titus’ Army vs Jewish Defenses

Waiting for the Romans in Jerusalem were 23,400 troops: 15,000 under Simon, 6,000 under John, and 2,400 under Eleazar. The Jews possessed “fortitude of soul that could surmount faction, famine, war and such a host of calamities,” wrote Josephus.

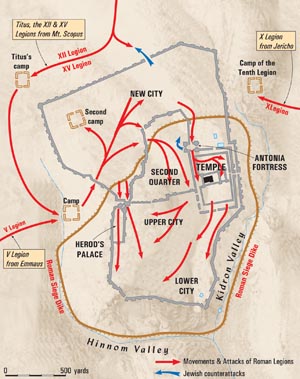

Jerusalem was divided into three parts: the 100-acre upper and lower cities in the south, the 150-acre new city in the north, and the 50-acre Temple Mount in the east. The Temple Mount, which crowned Jerusalem, was positioned like a lock connecting the northern and southern sections of the city. Attached to the northwest corner of the Temple Mount was the formidable Antonia Fortress. Within the city were two inner walls. The first wall divided the northern and southern sections of the city while the second wall afforded an additional layer of defense in the new city.

The vanguard of Titus’s army cut off communications between Jerusalem and the surrounding countryside upon its arrival in April. Titus cleverly added to the confusion within Jerusalem by allowing pilgrims to enter to celebrate Passover. He had no intention of allowing them to depart, though. He knew that the presence of large numbers of noncombatants would strain the city’s food resources. As expected, famine quickly set in.

Titus ordered Legions V, XII, and XV to bivouac on Mount Scopus to the northeast and Legion X to encamp on the Mount of Olives to the east. The Jews conducted repeated sorties against the camps that forced Titus to tighten his siege. As the siege progressed, the camps would move closer to the front lines, eventually occupying part of the western portion of the new city.

Titus reconnoitered the city and decided to begin his assault on the level ground outside the new town. The Romans punched through the outer wall and the inner wall in just 24 days of fighting. They used bronze-headed battering rams to crack the walls. Roman catapults hurled stones into the center of the city to destroy defenses and inflict casualties.

But Titus’s initial success, and the casualties he inflicted on the defenders, did not stop the Jews from fighting among themselves. John launched a surprise attack against Eleazar’s troops holding the Temple in which his troops slaughtered Eleazar’s men. When the fighting resumed between the Romans and the Jews, John’s troops were in possession of the Temple Mount and the Antonia Fortress, while Simon’s were deployed along the first wall in defense of the upper and lower city as well as Herod’s Palace.

Titus subsequently separated his forces in order to attack each of these groups, but the focus of the siege and of the fighting soon moved to the Temple Mount. The Romans began to build ramps against the Antonia Fortress, and their construction went on day and night, with the Roman forces being attacked by hundreds of bolt shooters and stone throwers the Jews had captured from the Roman army.

While some Jews harried the Romans from above, others were tunneling beneath their position and filling the space with bitumen and pitch. Suddenly, the ground beneath the Romans collapsed, and the siege ramps and towers fell into the burning pits. It was a major setback for the Romans.

The heavy casualties the Romans had suffered in the house-to-house fighting and in the destruction of their ramps and towers compelled Titus to rethink his strategy. Titus had lost a large number of men in the fighting to that point, and he feared even greater losses trying to take the inner bastions of the city.

The Roman commander decided it would be advantageous to tighten his blockade on the city. Titus therefore ordered his troops to construct an encircling line around the city to ensure that the Jews could not smuggle in supplies. The circumvallation line was 41/2miles long and was strengthened at intervals with 13 forts. In addition, he issued orders that anyone found outside of the city was to be crucified.

“Pitiful was the fare and lamentable the spectacle, the stronger taking more than their share, the weak whimpering,” wrote Josephus. “Wives would snatch the food from their husbands, children from fathers, and—most pitiable of all—mothers from the very mouths of their infants.” Deserters who were allowed out of the city told of corpses everywhere stacked up and left unburied. So crazed with hunger were the defenders that they resorted to eating leather belts and harnesses. Josephus himself appealed to the combatants to give up, at least for the sake of the starving, but he was ignored.

Yet somehow the defenders found the strength to fight on. They repaired breeches in the walls made by the battering rams and repulsed fresh assaults by the Romans. The Romans explored every possible avenue of attack. In late July, the Romans conducted a night sortie that overwhelmed Jewish sentries who had fallen asleep at their posts guarding the Antonia Fortress. Next, Titus focused his efforts on capturing the Temple Mount where the Jewish forces had concentrated in expectation of a final battle.

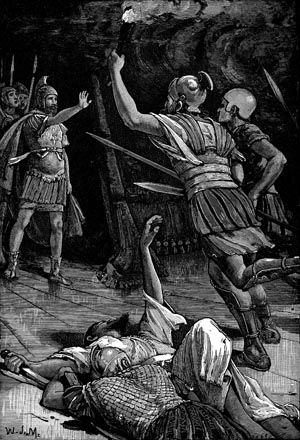

Although the northern end of the Temple Mount’s colonnade had been almost completely destroyed by that point, its western end was still intact. On July 27 the Romans were at work on a series of platforms that would link it with the remains of the northern end. Suddenly, the Jewish rebels atop the western end dispersed, leaving it undefended. Some of the Romans probably guessed it was a trap, but the chance to gain control of the elevated colonnade roof was simply too good to pass up. They should have trusted their instincts for the Jews had packed the cedar rafters beneath the colonnade with bitumen, pitch, and dried wood. When the Romans climbed their ladders and reached the roof, the rafters below them burst into flames.

The 50-foot-high colonnade collapsed, sending hundreds of Romans down into the city. Those who had advanced beyond the collapsed area had nowhere to go when the flames consumed their ladders. “Encircled by the blaze some flung themselves down into the city behind them, some into the thick of the foe; many in the hope of escaping with their lives jumped down among their own men and broke their legs; most for all their haste were too slow for the fire; a few cheated the flames with their own daggers,” wrote Josephus. The remaining individuals, many of whom were severely wounded, eventually succumbed to their wounds.

For all of their elation, the Jews merely had delayed the inevitable. Sensing that victory was near, Titus pressed the siege of the Temple Mount. Each day he sent legionnaires forward to ram and batter the walls. But the walls were too well made and the individual blocks too thick, so that even prying a handful of them free did nothing to the walls’ overall integrity. Frustrated, Titus ordered that the Temple Mount be stormed, but this only led to more lives lost and more standards captured by the enemy.

The Jewish destruction of the western colonnade, while briefly affording the defenders an advantage, had nevertheless made their position vulnerable. When the Romans decided to destroy the northern colonnade, the Jewish forces secured themselves within the walls of the Temple complex.

The Temple Mount and inner courtyard were surrounded by thick walls and a handful of strong towers. The Temple alone soared 150 feet into the air. The entire complex, known as the Platform Mount, was itself built atop a dais. The series of walls, boundaries, balustrades, gates, and impediments were meant to halt one’s progress toward the earthly home of the Jewish God behind golden gates. It was within sight of these gates that the remnants of the starving Jewish forces made their last stand.

The Jews sallied forth on August 9 and attacked the Romans holding the outer court. After three hours of see-saw fighting, in which the Jews bore the brunt of a Roman cavalry charge, the Jews retreated to the inner court once again.

The following day the Jews attacked the Romans in the outer court again but found themselves trapped against the northern wall of the Platform Mount. Someone hurled a flaming torch over the wall and into the Sanctuary surrounding the Temple. No one knows who did it or why.

If the cessation of the sacrifice had demoralized the Jews, the entire reason for that sacrifice, and for the revolt, was being destroyed. The Jews’ defensive line and their very religion, the source of their strength both physical and spiritual, were collapsing at the same moment. Chaos, disorder, and looting ensued. The Romans gave no quarter.

“There was no pity for age, no regard for rank; little children and old men, laymen and priests alike were butchered,” wrote Josephus. He added, “The cries from the hill were answered from the crowded streets; and now many who were wasted with hunger and beyond speech found strength to moan and wail when they saw the sanctuary in flames.”

Aftermath in the Sacred City

Whatever sympathy Titus may have once had for the Jews, whatever respect or awe he may have once given the Temple, and whatever worries he may have once given to the notion of Rome acting too harshly toward the rebellion disappeared altogether. He ordered a victorious sacrifice near the eastern gate of the Temple. One of the animals burned there, which was the most insulting and blasphemous of all, was a pig.

The insurgents who remained held out for many months. Herod’s Palace was laid to siege and finally destroyed, and by the next summer, even as Titus and Vespasian were celebrating a triumph in Rome, their forces were still clearing Judea of fighters. Captured Jewish men were sent to either live out their lives in forced labor in Egypt or to be torn apart by animals in gladiatorial games, while their women and children were dispersed and sold as slaves. The whims of the new regime also meant that the rebel leaders met with different fates. John was sentenced to life imprisonment, while Simon was systematically tortured and scourged before being strangled. In Judea in ad 73 and 74, the Romans conquered the hilltop fortress of Masada, bringing the First Jewish War to a bloody conclusion.

Titus took home to Rome as trophies of his victory the golden table of shewbread, the seven-branched candlestick, and a roll of the Law. Shortly after Titus’s death in ad 81, his brother Domitian had the Arch of Titus erected on the Via Sacre in Rome. In one of the reliefs depicting the destruction of Jerusalem, Roman soldiers are seen carrying off the seven-branched menorah and trumpets, holding them high over their heads.

The Romans forbade the Jews from rebuilding the Temple, established a permanent garrison, and abolished the Sanhedrin, replacing it with a Roman procurator’s court.

Josephus, who had correctly predicted the rise of Vespasian, was at Titus’s side during the fall of the city. After the war he became a Roman citizen and was given a pension and an imperial residence in Rome. He spent the rest of his life writing not only a history of the war, but of his people, narrating for Greek and Roman readers the story of the Jews from the creation of the world to the revolt.

To the end, Josephus defended Jewish culture and norms against the supposed superiority of Greek knowledge and philosophy. As Temple Judaism disappeared and Christianity spread over the known world, Rabbinic Judaism rose from the horror and bloodshed of the revolt and from the ashes of the Temple. In the end, Jerusalem survived Rome.

I am somewhat doubtful about the claim that Titus wanted to stop the Temple from burning. What was his motivation? Josephus is considered a reliable source from that era, however, he was scrutinized by his Roman bosses. Perhaps the claim about Titus was a politically motivated one. But, then again anything is possible.

“Temple by entering the Holy of Holies, which no one but the High Priest was allowed to do, and that only once a year, merely to survey its riches”

Correction: The High Priest entered into the Holy of Holies (“Kodesh Kodeshim”) on Yom Kippur, or the Day of Atonement, as part of that day’s service. Any valuables that were owned by the Temple were stored in a different area. There were no vessels in the Holy of Holies during the Second Temple era.