By Alan Davidge

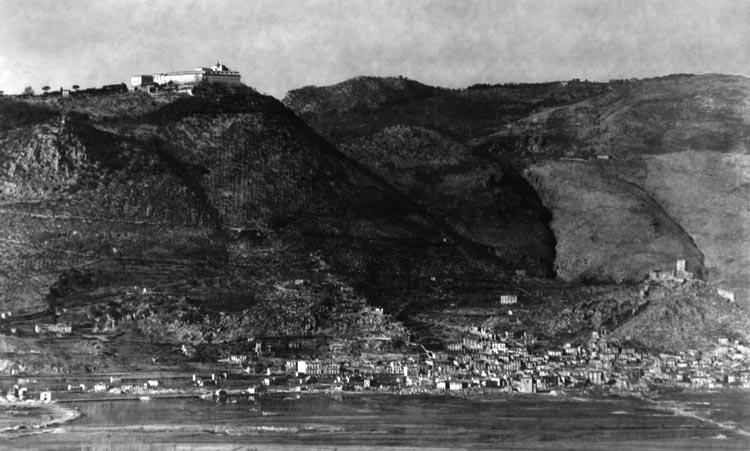

It was March 14, 1944, and Private Albert “Albie” Duddy of D Company, 1st/4th Battalion Essex Regiment, was staring up at the monastery on top of the hill at Monte Cassino from a location north of the town of Cassino, Italy. A coded order had been given: “Bradman bats tomorrow.” To those unfamiliar with Anglo-Australian cricket, this meant that his battalion would be leading the frontal attack on Monte Cassino that would finally dislodge the Germans from the Gustav Line and open up the route to Rome.

When visiting battlefields, it sometimes takes time to recognize the salient features and to deduce where the action actually took place. For anyone who approaches Monte Cassino, however, there is no doubt of its identity. Towering above its town is a hill strapped across by hairpin bends that look challenging to a modern-day motorist. For an army under fire in the depths of winter, this is clearly not an objective that would have been conquered easily.

The Allies had been trying since January, and many of those unlucky enough to fall victim to enemy fire during that cold, bleak winter still lay on the slopes of the hill. There were high hopes that this third battle of Monte Cassino would be the decisive one.

“I’d just had enough, I didn’t think I could go any further,” Albie told the author 40 years later. The strain of the war had finally gotten to him. A chirpy East Ender, Albie had served at both battles of El Alamein and fought his way around much of the Mediterranean with the British Eighth Army before landing in Italy and preparing for the final push.

As Albie was taking stock of what fate had in store for him that morning, his lieutenant quartermaster appeared. “I’ve asked for a man to stay behind tomorrow to help me. D’you fancy it?” The reply was immediate and affirmative, but for the remainder of D Company, and indeed the whole battalion, Fate was busy preparing a very different set of cards.

It would be difficult to find a more typical set of “Tommies” than the 1st/4th Essex. Although B Company was largely recruited from the flat, marshy areas of the Essex countryside, the majority of the battalion came from London’s East End, Cockney boys whose childhood in streets of terraced houses where little was owned and much was shared had taught them to be resourceful and self-reliant, giving them a loyalty to their families and their neighborhoods.

As news filtered through of Hitler’s Blitz steadily demolishing those streets and the docks and the places they called home, they became even more protective and keen to deal with the perpetrators. D Company came largely from East Ham, close to the docks and the recipient of many a stray bomb.

Some would have grown up as neighbors to singer Vera Lynn, “The Forces’ Sweetheart,” another East Ham local whose contribution to the morale of Allied troops was incalculable and who, at age 103, is still held in the highest esteem across the globe.

Together the Essex were a formidable fighting force, with a camaraderie and sense of humor that melted the resolve of many an officer, and who could be excused the occasional misdemeanor because, when there was a difficult job to be done, their track record was one of giving their all.

Previous attempts to deal with the German troops who were dug in on Monastery Hill had been messy, controversial, and very expensive in terms of casualties sustained.

It hadn’t been easy for the Germans, either. Apparently Hitler had wanted to move all of his men and resources to the north of Italy once the country had been invaded in the south in September 1943. However, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, whom he had placed in command of the Italian theater of operations, convinced him otherwise with a plan that put as many obstacles in the way of the advancing allies as possible, slowing them down and sapping their resources and willpower, especially during that awful winter of 1943-1944.

The Gustav Line, 100 miles south of Rome, followed a series of natural barriers across the country, crowned by the heights of Monte Cassino with its 1,400-year-old Benedictine monastery. “Get though the Gustav Line and Rome is yours,” taunted the elite 1st Paratrooper Division through their strongpoints on the hill, knowing that, in addition to their own formidable reputation, they also had the weather and the topography on their side.

The British Eighth Army under General Bernard Law Montgomery and the U.S. Fifth Army under Lt. Gen. Mark Clark had landed in Italy in September 1943, the month that Italy capitulated. With the Italians now their allies, they headed north for Rome via Highway 6 but ground to a halt in the Liri Valley near Cassino in December as the winter closed in.

On January 17, 1944, the first battle of Monte Cassino was initiated with British XX Corps in the lead, assisted by U.S. and French troops. American and British soldiers of the U.S. 6th Corps were scheduled to land at Anzio on January 22, and it was felt that this battle could have the additional advantage of diverting German resources at a crucial time.

By February 7, Point 445, directly below the monastery at Monte Cassino, had been taken by the Germans. The monastery itself was kept off-limits on the orders of Kesselring, although German troops were occasionally reported using it for observation purposes.

February 11 saw a major U.S. assault on Monastery Hill and the town of Cassino that lasted three days, but this resulted in 80 per cent infantry casualties, and the survivors had to be withdrawn. On the German side, General Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin saw the slopes of the hill as a killing field comparable to the Somme, and suggested creating a new line of defense; but this was turned down by Kesselring.

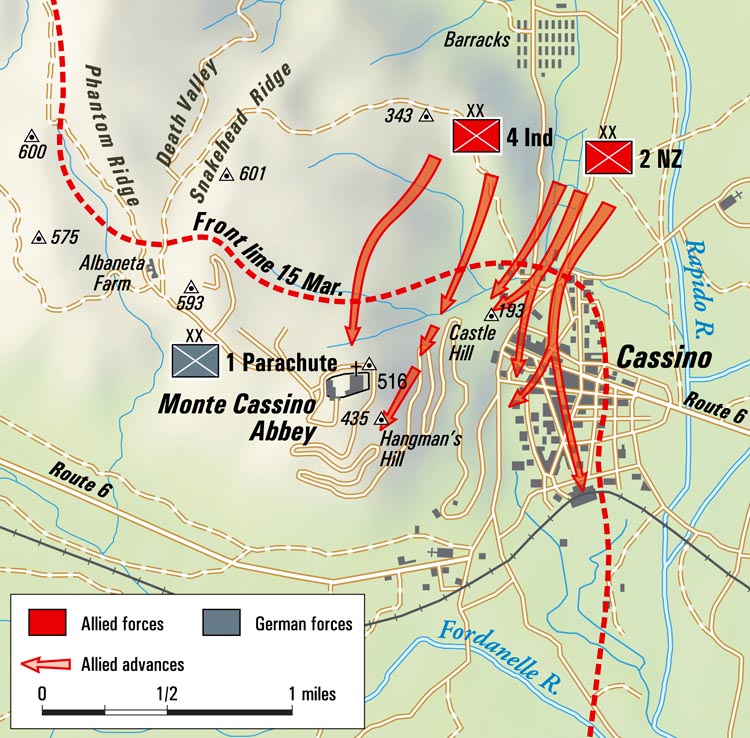

The arrival of the New Zealand 2nd Division and 4th Indian Division (which included the 1st/4th Essex) at this point gave fresh hope of a breakthrough, but this time a different strategy was proposed. Maj. Gen. Bernard C. Freyberg, the New Zealand commander, began in earnest to help take pressure off Anzio by continuing the attack along the ridges close to the monastery and also launched an attack along the railway line south of Cassino town to gain control of the station.

New Zealand troops paid a heavy price for trying to forge a way through the town to support their Allied comrades. Everard Otto reported on the 28th Maori attack on the station, “One hundred-and-twenty-eight were killed and many wounded. It was gruesome.”

The main change to the previous strategy, however, involved the monastery, whose neutrality was continuing to be a great source of debate. Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Keyes of the U.S. II Corps flew over several times and observed no Germans, so he did not consider it a threat.

However, Maj. Gen. Howard Kippenburger, in charge of the New Zealanders, and Maj. Gen. Francis I.S. Tuker, commanding the 4th Indian Division, saw it as more of a danger if left intact. Mark Clark, U.S. Fifth Army commander, was against bombing the monastery and referred the decision to the British General Harold Alexander. Alexander’s final decision cast the die, and preparations were made for one of the most controversial acts of the entire war.

On February 15, a total of 142 B-17 Flying Fortresses, 47 B-25 Mitchells, and 40 B-26 Marauders unleashed 1,150 tons of high explosives and incendiaries on the monastery. Between bombing runs it was smothered by artillery; the following day more shells and more bombs rained down on the ruins.

There was no evidence of German casualties being sustained either in the monastery or at the strongpoint outside near Snakeshead Ridge (Point 593). However, around 250 civilians sheltering in the building were killed. Seizing the opportunity, the German 1st Paratrooper Division immediately occupied the ruins and turned them into a fortress.

The first attack of what became known as the Second Battle of Monte Cassino took place the night after the bombing. From the 4th Indian Division, the Royal Sussex attacked Point 593 from Snakeshead Ridge, losing 50 per cent of their men. Another regiment then tried, suffering a similar fate.

The following night, February 17, saw the 4th Indian in action again: 4/6 Rajputana Rifles attacked Point 593, 1/9 Gurkhas hit Point 444, and 1/2 Gurkhas tried a frontal assault, all sustaining heavy casualties. The hill was eating soldiers like the Flanders mud had 27 years earlier.

The persistent wet weather slowed down further attempts to break through the Gustav Line, but a plan was being developed that combined a powerful surge by the New Zealanders into the town of Cassino together with a frontal attack on Monastery Hill by the 5th Indian Brigade, consisting of the 1/9 Gurkhas, 1/6 Rajputana Rifles, and the 1/4 Essex as lead battalion.

It would be ignited by a bombing raid on Cassino town which, unfortunately, would require three consecutive days of good weather; it took until March 15 before this became possible. This was the start of the Third Battle of Monte Cassino.

The bombing of the town had a devastating effect on the Germans stationed there. It lasted three-and-a-half hours and involved 775 bombers unloading 1,000 tons of high explosive on roughly one square mile.

The raid represented nearly the same tonnage of bombs that had destroyed the monastery the previous month. Even those able to shelter in the cellars took a long time to recover their senses. It was, however, so effective that the resulting damage and rubble in the streets made it very difficult for New Zealand tanks to occupy or pass through the town, which delayed this new plan right from the start.

The Essex were less than enthusiastic when they received their orders. A Major Beazley, commanding B Company, explained that it would be a frontal attack. The previous attempts had involved maneuvers around the massif, but this one, Beazley said, would have surprise value. Private Tom Stringer expressed the misgivings of the attack: “When we saw what was in front of us, we thought it would be a hopeless task.”

The first step up the hill was an imposing piece of rock with a medieval castle perched on top of it containing a keep and courtyard, which became known as Castle Hill. It had successfully been taken by D Company of the 25th New Zealand Battalion in late afternoon of March 15 after the bombing of the town.

The role of the Essex would be to lead the 5th Indian Brigade attack, relieve the New Zealanders, and, together with the Gurkhas and Rajputanas, climb Monastery Hill to a feature 300 yards from the top that they called Hangman’s Hill. It was so named because of the pylon on top of it, which bore a resemblance to a gallows.

This would require the brigade to systematically take each of the hairpin bends on the route to the summit and silence those that were occupied, while other battalions could pass through and repeat the exercise further up the slope. Once assembled in force on Hangman’s Hill, they would storm the monastery and take Highway 6 into Rome—a straightforward plan on paper, and easier said than done.

Once again the weather, abetted by the delays caused by the bombing that had created enormous access problems in the town, took its toll. The start time for the Essex, sheltering in the rocky outcrops of Wadi Villa, was delayed by two hours, and they did not begin until 7 p.m., by which time it was already dark.

The Essex struggled up Caruso Road in the wet, and the darkness brought no relief from the shelling they had been experiencing most of the day. They followed tapes left behind by the New Zealanders, but frequently found these had been blasted away by shellfire.

With hindsight, it would perhaps have been more effective for the Gurkhas to take the lead. The Essex boys had great strengths, but climbing was not one of them. Essex is one of the flattest counties in England, but the Gurkhas were brought up in Nepal, and their families regularly acted as sherpas on expeditions in the Himalayas. Their direction-finding and ability to pass swiftly and deftly over uncertain terrain were to become apparent later on in the assault.

Essex A Company began the climb to Castle Hill, followed by C Company. Major Dennis Beckett, commander of C Company, went on ahead to determine the actual entrance to the castle. He was greeted by a New Zealand officer who asked him: “What took you so long, Cobber? Here’s your castle, don’t lose it.”

Beckett later gave a detailed description of the operation: “To begin with [on March 18], I completed the relief of Point 165 with the 1/6th [Rajputana Rifles] at 0330 and concentrated my company in the Castle. Frank [Major Frank Ketteley, commanding A Company, 1/4th Essex] and I were to leave two hours later than B and D, as our preparations were not so well advanced owing to the change of plan.

“At 0400, B and D moved from the Castle, and a little before 0500 Command Sergeant Major Cox and about six men from B Company came running back to say that a very large number of Germans, whom they had first thought to be an Indian carrying party until noticing their helmets, were advancing on the Castle. We were in a pretty fair state of chaos. The 1/6th were supposed to have taken over the defenses, but in fact most of our men were still in the breastworks, and we were trying to issue rations and ammo, and sort out weapons which had been buried among the debris during the tank shoot the previous day.

“However, Frank gave the order ‘stand-to,’ and everyone ran to their posts. The Indians did not quite know what to do, naturally, and eventually gathered in a herd at the back of the Castle, although a few fought very bravely in the courtyard and some did magnificent work as snipers. I do not make this criticism of the Indians unkindly as there was really nowhere for them to go as we had already occupied the defenses and there was very little room for anyone else on the perimeter.

“The situation was now 1/6th in possession of Point 165, and 1/4 and elements of 1/6th Point 193. The enemy counterattack opened with intense machine-gun fire sweeping the Castle. I have never known anything like it. It came from every angle. This lasted for about 10 minutes, then they were on us.”

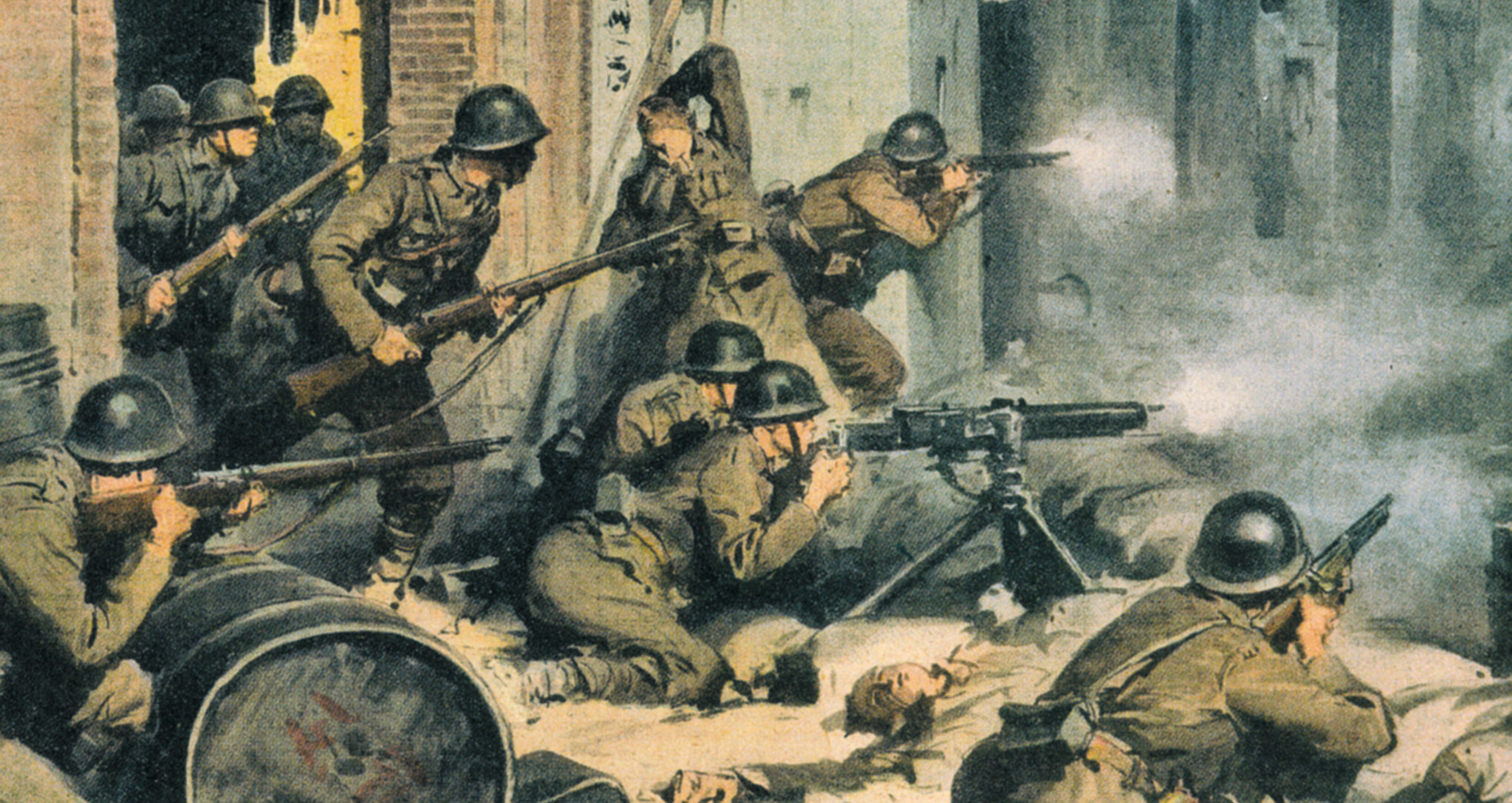

Beckett continued, “We could not use artillery D.F. [defensive fire] because we did not know how the Raj Rif or our own people were faring out in front. Our mortars had not then been registered. It had to be fought out with infantry weapons man to man. Frank went on the blower to tell Battalion whilst I did the best I could to organize the defenses.

“The men were a bit shaken by the intensity of the fire, so, more to encourage them than anything else, I got a man to spot and fired about a dozen 2-inch mortar bombs at a wave advancing under the castle wall. The first attack very nearly succeeded. One or two tried to penetrate the courtyard, and many were stopped only a few yards from the walls. We broke them up with Mills grenades, Tommy guns and Brens.

“Frank now became eager to take a more active part in the battle and crawled forward to pick off a machine gunner who had been giving us trouble. He was the fellow who had wounded me twice slightly in the arm and neck a little earlier. Unfortunately, the Boche got Frank first, straight through the head and he died not long after.

“We threw a number of Mills grenades in the direction of the machine gunner and had no trouble after this so I presume we must have got him. Soon afterwards we saw a white Verey light [flare] go up and the small-arms fire was replaced by artillery and mortar fire so we assumed the first counterattack had been driven off.

“I took stock of the situation. It was not pretty. We had about eight 2-inch mortar HE [high explosive] bombs left, 12 grenades, a fair amount of Tommy guns, and by good luck a lot of .303 [ammunition]. We had lost a few good chaps in the first machine gunning, among them, I think, Pat Coghlan, and a number were wounded trying to take up fire positions on the walls.

“The lull did not last long. The enemy had taken advantage of his first push to occupy very favorable ground, and this time began with a shower of stick grenades. But we too were more prepared, and I had been on to Battalion to arrange for our Vickers guns to bring enfilade fire on the western end of the Castle. The 3-inch mortars, too, were used with telling effect, though the problem here was to find a place to observe from.

“Eventually I climbed on top of a wall exposing head and shoulders. I was a complete bloody fool to do this. Everything I had been taught since O.T.C. days ought to have warned me against it but I could see no alternative. Anyway, a little runt of a Boche chucked a grenade at me and I was lucky not to get it on the head.

“By sheer luck we got the correction through before this happened, so it was with some thrill that we heard Hugo’s boys crumping down on the wicket and the tapping of their Vickers guns. I think this pinned the Boche for a bit because we were able to reorganize a bit. Just afterwards I got a message from Robin Oswald, B.C. of 52 Battery (lst Fd RA) to say they were dreadfully thin on the ground in the courtyard and short of ammo. They had suffered heavily from Boche grenades and were in a bad way. A force was organized under Doug Beech consisting of Ronnie Ulph and about 12 men of A Company carrying bags of ammo to go and help out.

“To get these across, we lined up the Brens on the inner wall and blazed away at the openings while the leading members of the party also shot their way across with Tommy guns. They got across without casualty as far as I can remember. The courtyard had been the scene of the toughest fighting. Three times the Boche had penetrated. Several times they had climbed the walls only to be driven off.

“On the Cassino side, Corporal Parker, fighting his post with inspiring coolness, broke up a wave on his own, firing the Bren until the enemy were within a few yards and then finally smashing the attack with Mills grenades.

“Around the tower were some old arrow slits. These were manned by Bren gunners to cover the gaps in the walls. The Boche very quickly realized the nuisance value of these. I saw three of our chaps go down in succession, shot through the head, and a little fellow from B Company pick up a rifle and say quietly ‘I’ll get him, Sir.’ He waited till the man’s shadow appeared on the wall and shot him dead. A German prisoner, who had been wounded, now came in and on cross-examination said 200 of them formed up for the first counterattack and 40 for the second. He said they came from the Monastery.

“Battalion now warned us to expect a third counterattack and asked if we could state whether Point 165 was clear of our own troops. Capt. Jenkins (1/6th) said he had not been in touch with his men for two hours and would assume they had been overrun. Heavy fire was therefore laid on very close in, and as soon as the attack commenced a full blunderbuss of arty., mortars, mmg’s and small arms was brought to bear.

“This counterattack was supported by a tank from the road bend above Point 165, and a systematic shoot aimed at the destruction of our west wall commenced. As a result, the wall collapsed, burying about 10 of our men, including Capt. Beech and Lieut. Ulph. However, the attack was not pressed home due, l think, to the effectiveness of our supporting fire, which continued in the face of heavy enemy artillery fire on our mmg’s, a fact which gave great heart to the defenders. Once again the enemy withdrew under a concentration of arty and mortars, and no fresh counterattacks developed.”

By midnight the handover had finally taken place, but the misfortunes continued. The last two companies of the 1/6 Rajputana Rifles who followed the Essex were decimated by an artillery barrage and took no effective part in the battle from then on.

Essex C Company, still in the pitch dark, then took Point 165, one of the crucial hairpins, from the Germans; two companies, A and B, of the 1st Rajputana passed through them, hoping to take Point 236, a major German strongpoint and observation post. It was now 4:30 a.m. They were spotted as they prepared to attack, and the fierceness of the machine gun and artillery barrage forced them to retreat to the Castle.

The third battalion of the brigade, 1/9 Gurkha Rifles, following behind, had been tasked with leapfrogging the Rajputanas once they had taken Point 236 and carrying on to Hangman’s Hill. Their commander, Lt. Col. Nangle, was now faced with a difficult decision and eventually decided to deploy Companies A and B by the Castle and send C and D forward to accomplish as much as they could.

Not only was the brigade a sitting target for the Germans, but the whole route upwards was becoming incredibly congested. C and D Companies moved up, avoiding the main track, and when their path split, they separated. The route followed by D led them into a hail of Spandau fire, costing them 15 of their men within a minute. Contact was later lost with Company C, and the brigade could only assume they had met a similar fate.

During the course of the next day, the Rajputanas made further attempts to take Point 236, gaining it and then losing it to a counterattack. Then at 2:00 p.m. came the first piece of encouraging news. The missing Gurkha company had arrived at Hangman’s Hill, kicked out the Germans who were occupying it, and were only 300 yards from the gates of the monastery. They had achieved what no other battalion had done on the hill—to find a route off the beaten track, slip past the Germans, and take a major strongpoint by surprise.

All efforts were now concentrated on getting the remaining Gurkhas up to join them; the climb started at 8:00 p.m. By the early morning of the 18th, the Gurkhas were established together on Hangman’s Hill. They were not planning a long stay and, although well equipped as regards ammunition, they had sacrificed rations and clothing to facilitate their swift movement up the hill. This was to prove costly.

The Germans now knew they had to do everything possible to keep control of the strongpoint at Point 236, and they also realized that a significant force was in position to take the monastery. If they could isolate the Gurkhas and frustrate any attempts to supply them, the third battle of Monte Cassino could go the same way as the first two.

Back at the Castle, the 1/4 Essex war diary reported significant problems with snipers, so the battalion called upon their New Zealand comrades for help. However, their next orders would take them out of the Castle and into a new kind of danger.

It was decided that the whole battalion was to be relieved by the 4/6 Rajputanas and make its way to Hangman’s Hill to join the Gurkhas and storm the monastery. B and D Companies now had to make the night climb up to the castle in driving rain.

Ken Bond recalled the horrors: “We were slipping and sliding everywhere and were being attacked by machine guns. Men were falling over rocks. We never saw them again.” Ken and his mates arrived in the early hours of the 19th and continued on towards Hangman’s Hill, to be followed by A and C Companies as soon as the relief by the Rajputanas was complete.

Then something happened to stop everyone dead in their tracks. It was just before 6:00 a.m., and a group of about six men from B Company, who had set off to join the Gurkhas, suddenly arrived breathless back at the castle gates, having observed a large German force heading for the castle from the monastery.

In his account after the war, Tom Stringer said they heard voices in the dark. “Someone fired a Verey light and we saw them coming down the hill.” The German commander had realized the crucial strategic position of the castle and felt it was time for a change of ownership.

The men of B and D Company who witnessed this potential counterattack had to decide whether to advance as planned to Hangman’s Hill or go back and seek refuge in the castle; only about 70 made it through to join the Gurkhas. Tom Stringer was among these but was badly wounded. His rifle jammed as he tried to fight off the Germans, and he was then hit by several fragments of a grenade. He played dead till some German stretcher bearers came along and then asked for help. Wounded in three places and lucky to be alive, he resigned himself to what he called “The end of my time with the 4th Essex.”

Major Kettley of A Company, the senior officer on Castle Hill, rushed the Essex men into defensive positions with not a moment to spare as they were deluged by coordinated fire in support of the German 1st Parachute Division, who were planning to storm the castle wall. It came from the monastery, Cassino town, and points in between, pinning down the Essex troops for about 10 minutes.

Then 200 paratroopers tore down the hill from Point 236, through the hapless defenders at Point 165, tossed grenades over the walls, and prepared to take the castle. Major Beckett, organizing the defense while Kettley contacted headquarters, could only rely on grenades and small-arms fire to break up the attack, as calling in artillery could cause casualties amongst his own men, who were also out there somewhere on the hill.

The Essex defenders broke up the attack, but only just. In all of their military training, they would never have expected to take part in a pseudo-medieval siege, firing from the battlements and arrow slits of a castle. Those who survived to raise families and take their children to watch The Alamo in the 1960s must have also sensed a form of dejà vu as they watched William Travis, James Bowie, Davy Crockett, and their small band of men try to hold back Santa Anna’s Mexican army.

The Germans withdrew, but not before killing Kettley and twice wounding Beckett. The next few hours were to become a defining period for the 24-year-old major. He summed up the situation, organized enfilading fire from Vickers machine guns on the other side of the ravine from the castle, and registered his mortars for the inevitable second wave. He then occupied a risky and exposed position on top of a wall to make the necessary adjustments once the firing commenced.

The paratroopers penetrated the courtyard three times, and fighting was hand-to-hand. One of the most unnerving experiences was the raining-down of stick grenades or “potato mashers,” which were returned by those brave enough to pick them up before they exploded.

While Beckett was taking charge and directing fire, other ranks were showing defiance in different ways. No Essex reunion in the post-war years was complete without a reminder of the tale of Sergeant “Rocker” Rose, who strolled along the battlements beating his chest and performing the famous Tarzan call.

At 7:50 that morning, the 1/4 Essex war diary records, “Brigade command sent personal message to A and C companies. You have done very well.” An understatement!

Beckett could not escape the feeling of being caught up in some bizarre piece of theater. The previous day, he had made up a white flag and ventured outside the walls with another man to bring in a wounded comrade without being shot at. Moved by this act of chivalry amidst so much carnage, he stopped and saluted his enemy before closing the gate. This may have generated a mutual sense of trust among the belligerents, as the termination of the second wave brought forth a white flag from the attackers.

Beckett then called an astonished headquarters to say there were German stretcher bearers outside the walls asking for a ceasefire to pick up their wounded, and he requested their approval. They were given 30 minutes, an act of compassion that was brought to a conclusion by a 25-pounder shell that sent everyone heading for cover and subsequently to take up their positions as enemies once again.

During that half hour, some remarkable events took place. Stretchers were shared, blankets were exchanged, and enemies sat down together and traded cigarettes. It was the 1914 Christmas Truce all over again.

Major Beckett then received the news that the 2/7 Gurkhas were below him and ready to push through to Hangman’s Hill to reinforce their comrades who were holding the hill with the men from B and D Companies of the Essex, who had set off earlier and joined the 1/9 Gurkhas and survived being swept up in the counterattack.

With this new input from 2/7 Gurkhas, there was a sizeable force with which to attack the monastery, but Beckett felt differently. The situation was close to stalemate, but the one thing in the Essex’s favor was that it held the castle, without which no progress could be made. He convinced his brigadier that this fresh Gurkha battalion should be kept back to help defend the castle rather than be sent up the hill and be rendered an ineffective fighting force before reaching its objective, like others before them.

Before long, there was yet another attack on the castle. A small party had crept forward and placed an explosive charge under a buttress, which blew open a hole large enough for a group of German paratroopers to gain access, as well as burying 20 of the Essex defenders, including Captain Beech. The Germans were brought down in a hail of bullets, and prisoners were taken, one of whom volunteered the information that 160 of the original 200 who had tried to storm the castle in the morning were now casualties.

Of the men from B and D Companies of the Essex who set off before the German counterattack, only 70 made it to Hangman’s Hill—and 30 of those had been wounded. Among them was Ted “Nutty” Hazle, who found he was the only medic in the group; he dutifully set up a Regimental Aid Post on the side of the hill.

At 4:30 p.m., the attack on the monastery was postponed yet again, and orders were given for the relief of A and C Companies in the castle and B and D at Hangmans’s Hill. The men in the castle were relieved by the British 78th Division and made their way back to Wadi Villa, from whence they had started four-and-a-half days before.

Only 21 men returned from A Company and 13 from C Company. For B and D companies, the journey was much more difficult, but a few struggled back. Next morning, March 20, 1/9 Gurkhas reported that 25 Essex men were still with them, and the C.O. ordered that they should remain and come under Gurkha command for the moment. Also in the early hours of the 20th, the officer commanding D Company arrived at Battalion HQ. He had started with 38 men and arrived back with four.

The most remarkable event of the Third Battle of Monte Cassino must surely be the Essex’s defense of the castle. Without the leadership skills and personal bravery of Major Dennis Beckett, it could have been a very different story. For his efforts, he was nominated for a Victoria Cross, the highest award for bravery in the British Army. However, he eventually received the Distinguished Service Order.

Band of Brothers aficionados could perhaps draw a comparison with Lieutenant Dick Winters’ leadership in the attack on the guns at Brécourt Manor, for which he was awarded a Distinguished Service Cross rather than the Medal of Honor, but this in no way diminishes the stature of the men concerned, who continued to gain the respect of everyone who served under them. Both of them returned home and lived into their 90s, with Beckett finally retiring as a major general.

Meanwhile, the 1/9 Gurkhas and the survivors from Essex B and D companies were still clinging onto Hangman’s Hill. They were perilously short of food and water, and Ken Hazle had the most meager of medical supplies. Parachute airdrops of food were organized, but many of them landed among the Germans.

Given the multi-national nature of the brigade, some soldiers found themselves very disappointed when the food they risked their lives to collect proved unsuitable for their needs; Essex men in 1944 had no use for chapati (an unleavened flatbread originating from India). Canteens were filled from a shell hole under cover of darkness to provide a water supply for three nights until the level fell and revealed a dead mule.

On the March 24, Hangman’s Hill was finally evacuated, and the remainder of D and B Companies rejoined their surviving comrades in Wadi Villa. Ted Hazle was awarded a bar to his Distinguished Conduct medal for his remarkable and tenacious work as the single medic available. Together with the remains of his battalion, he was moved out to Venafro, a town a little to the east, for their first proper meal in a couple of weeks.

Everyone knew it would take a long time to bring the battalion up to full strength, and it would never be the same again. Many of those who fought at Monte Cassino had joined up together when the war started and had become a closely knit family. They had served together throughout the Middle East, given Rommel a bloody nose at El Alamein, and made their mark on Italy.

The best that Major Dennis Beckett could say was that they had held on to the Castle. He knew, however, that this was no mean feat. If the Essex were to be judged by the Battle of Castle Hill, they were victorious. Brilliantly led, brave in the execution of their tasks, they had overcome overwhelming odds and could retire with pride. However, the Germans were still at the top of the hill, and Rome wasn’t any closer.

The Allies had to find another way to break the stalemate, which they eventually did. Alexander put forward a plan, Operation Diadem, that was inspired by the French General Alphonse Juin and that was as deceptive as it was bold. It involved stealthily moving troops from the Adriatic side of Italy to the west coast and attacking the Gustav Line along a 20-mile front—from Cassino to the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Diadem would involve the British Eighth Army, the U.S. Fifth Army, and, importantly, the Polish II Corps under General Wladyslaw Anders, which would follow the line that was pioneered by the Essex. The Canadian 1st Corps stood in reserve.

The troops took two months to deploy, and this was done gradually to keep the Germans guessing and maximize the element of surprise. The oncoming spring weather would provide an additional advantage. Once the enemy had been pushed back, U.S. VI Corps would break out of Anzio and cut off the Germans fleeing from the Gustav Line.

Diadem began on May 11 with a huge artillery bombardment from the Eighth and Fifth Armies, and the plan began to work, but the taking and then re-taking of the aptly named Mount Calvary at Point 593 on Snakeshead Ridge was horrendously costly for the Poles, whose casualties amounted to 3,800.

By May 13, the Germans gave way to the Fifth Army, and two days later the British 78th Division joined the line to isolate Cassino town, thus allowing the Poles to launch the long-awaited attack on Monastery Hill. The Germans retreated north to their pre-determined Hitler Line, and the Poles eventually raised the flag in the ruins of the monastery on May 18.

The night before this final battle, a Polish musician from the garrison at Campobasso, which stood in the shadow of the hill, composed a song which he called “The Red Poppies of Monte Cassino” as a tribute to his comrades. Although it became a Polish anthem, it reflected the sacrifices of all the nations that took part. The battles of Monte Cassino had cost the Allies 55,000 casualties and the Germans 20,000.

General Mark Clark pushed forward and arrived in Rome on June 5, seeking to stake his claim before the British and adding yet another controversy to the Monte Cassino story. But events on France’s Normandy coast the following day were to capture all the headlines and continued to do so for weeks. Dogged by controversy, Cassino was in danger of becoming a forgotten campaign.

The ridiculous story of the “D-Day Dodgers” didn’t help. Shortly after troops landed on the Normandy beaches, a rumor began circulating that Lady Astor, who is probably most famous for her duels with Churchill (“Sir, if you were my husband I would give you poison.” “Madam, if I were your husband I would take it.”) had labeled the men who had fought at Cassino as “D-Day Dodgers.” The truth behind the remark will never be known, but its very suggestion seriously undermined the sacrifices of the previous five months. The British troops, never known to miss the opportunity for some sarcastic humor, turned it on its head and composed a song that began:

“We are the D-Day Dodgers, in sunny Italy—Always on the vino, always on the spree…”

For the men of the 1/4 Essex, the campaign would never be forgotten, and the best they could do to give it some sort of closure was to come back and bury their dead. Later in May, the whole 4th Indian Division was given permission to return and perform a final act of respect to those comrades who had been like brothers to them for nearly five years. They lie now in the Commonwealth War Graves cemetery at Cassino.

The battles of Monte Cassino have become four of the most talked-about battles of the Second World War. The pendulum of successes and failures, the astonishing acts of bravery and defiance against all odds by both sides, the mutual respect and acts of compassion, and the ferocity of combat will continue to attract the interest of many a historian.

There much to discuss regarding the advantages and disadvantages of a multi-national force. Germany fought the campaign on its own, except for the limited help of Mussolini’s stragglers, who now called themselves the Italian Social Republic. The Allies included Brits, Americans, New Zealanders, Poles, Indians, South Africans, Canadians, Free French, Nepalese, and those Italian partisans who could at last say what they really thought about Il Duce.

Undoubtedly, there were advantages of sharing resources and combining the varied skills and expertise available—the kinds of attributes that are usually put forward by modern-day CEOs justifying a major merger. However, the delays in decision making when commanders could not agree, the egos involved at the top level, and the communication difficulties between different languages and cultures presented a variety of challenges and lessons to be learned.

Essex boys have eventually learned to love their chapattis, however. Walk into an Indian restaurant after the pubs have closed on a Saturday night in the county of Essex or London’s East End and there they are, using them to mop up their curry sauce like any seasoned Rajputana.

Albert Duddy rejoined the few mates who remained from D Company after they limped down exhausted from Hangman’s Hill. His battalion was joined by replacements from home, eager to do their bit and finish off the war. Together they fought on, initially up in the hills with the Italian partisans, until the war came to a close.

When he returned to East Ham, he began looking up old friends, some of whom had been captured earlier in the war and had now been brought home and demobilized. Unknown to him, his best mate, Joe Davidge, who had been captured by the Italians at Mersah Matruh when the battalion was surrounded and had to break out in the middle of the night, was also looking for him.

One night, in the Central Arms, Albie’s local pub in East Ham, Joe heard Albie’s familiar voice. Reunited after three hard years, they had plenty of stories to tell and at the end of the evening, Albie said to Joe, “Why don’t you come home and meet my sister; she was at school with Vera Lynn, you know.” Joe accepted his invitation, and that is how Joe Davidge’s best mate Albie became this authors’ Uncle Albie. The rest, as they say, is history.