By Victor J. Kamenir

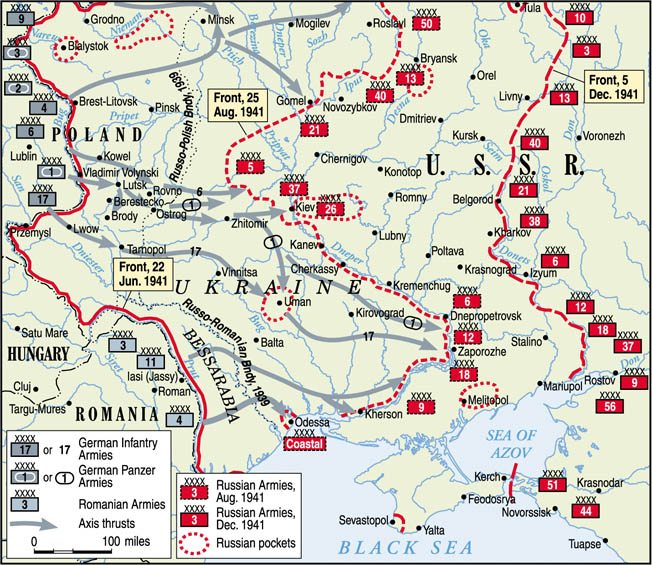

In 1941, the year of the Battle of the Bloody Triangle, the northwestern corner of the Ukraine was not what one would call tank country. With the exception of a few narrow, poorly maintained highways, movement was largely restricted to unpaved roads running through terrain dominated by forests, hills, small marshy rivers and swamps. Yet, during the first week of Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, a tank battle involving up to 3,000 armored vehicles took place there. This struggle in a roughly triangular area bounded by the cities of Lutsk, Rovno and Brody, became the forerunner of the brutal armored clashes on the Eastern Front.

On June 22, 1941, Panzer Group 1, the armored spearhead of German Army Group South, breached the Soviet lines near the border town of Vladimir-Volynski at the juncture of the Soviet Fifth and Sixth Armies. As a result of this skillful tactical move, a gap 40 kilometers wide allowed the jubilant Werhmacht troops to pour into Soviet territory. The Soviet Fifth Army, commanded by Major General M. I. Potapov, bore the brunt of the enemy thrust desperately attempting to slow the German tide.

The German operational plans called for a rapid advance to the Ukrainian capital of Kiev, capturing it and reaching the Dnepr River just beyond the city. After achieving this objective, the German troops were to swing south along the river, trapping the bulk of forces of the Soviet Southwestern and Southern Fronts (Army Groups). The capture of Lutsk, an important road nexus, would allow the mobile German units an opportunity to break out into open terrain and advance along two axes to Kiev: the Lutsk-Rovno-Zhitomir-Kiev thrust and the Lutsk-Dubno-Berdichev-Kiev thrust.

Kirponos’ Unrealistic Orders

At the end of the first day of war, Lieutenant General M. P. Kirponos, commander of the Southwestern Front, received instructions from the Soviet National Defense Committee to immediately counterattack in the direction of Vladimir-Volynski, destroy the German forces operating from that area, and occupy the city of Lyublin by the end of June 24. The fact that the city of Lyublin was located over 80 kilometers inside German-occupied Poland caused General Kirponos to wonder if the Soviet High Command really understood the unfolding situation on the border.

Even though he realized that his mission was unrealistic, Kirponos was obliged to carry out his order. The problem facing him was two-fold. Not only was the Soviet defensive situation unstable, but the five mechanized corps earmarked for the counteroffensive were spread throughout the northwestern Ukraine. It would take some units up to three days to arrive in the area of operations. Therefore, all five mechanized corps would be committed into combat piecemeal, with marginal or non-existent cooperation among them.

Even though he realized that his mission was unrealistic, Kirponos was obliged to carry out his order. The problem facing him was two-fold. Not only was the Soviet defensive situation unstable, but the five mechanized corps earmarked for the counteroffensive were spread throughout the northwestern Ukraine. It would take some units up to three days to arrive in the area of operations. Therefore, all five mechanized corps would be committed into combat piecemeal, with marginal or non-existent cooperation among them.

The tight schedule did not allow Kirponos sufficient time to concentrate his forces and adequately prepare for the counterattack. To further complicate the situation, many units of Soviet mechanized corps were mechanized in name only. Many regiments of the motorized infantry divisions lacked wheeled transport, and many artillery regiments were woefully short of prime movers. There were widespread shortages of communications equipment and artillery, especially armor-piercing ammunition.

As the Soviet mechanized formations began moving toward the border, the German Luftwaffe launched relentless and merciless air attacks on the armored columns strung out along the narrow roads. Often, the Soviet drivers, desperately trying to maneuver for cover, became bogged down in the difficult terrain and had to abandon or blow up their vehicles. The attrition of poorly maintained armored vehicles due to mechanical breakdowns began to reach alarming proportions. Due to losses from air attacks and mechanical failures, some Soviet tank formations eventually went into action with less than 50 percent of their operational strength.

Still, the forces converging on the Panzer Group I were formidable, almost double the number of panzers available to Lieutenant General Paul L. Ewald von Kleist. The actual pre-war strength of the five Soviet mechanized corps consisted of roughly 3,140 tanks. Even allowing for a large percentage of non-combat losses during the approach to battle, these numbers still dwarfed the approximately 618 tanks that were available to the German commander.

In the early afternoon of June 24, one of the tank divisions of the 22nd Mechanized Corps came into contact with the advancing Germans west of Lutsk. This division, the 19th, was severely brutalized by the German air attacks during its approach and was plagued by mechanical breakdowns. Its remaining 45 light T-26 tanks and 12 armored cars were combined into one provisional regiment and committed into action after a short preparatory artillery barrage. A seesaw fight with the units from German 14th Panzer Division raged for two hours during which the Soviet unit lost most of its remaining armored vehicles and was forced to fall back to nearly 15 kilometers west of Lusk.

The fight was costly for both sides. The commander of the 22nd Mechanized Corps, Major General S. M. Kondrusev, was killed, and the commander of the 19th Tank Division was wounded. All the regimental commanders in the division were also killed or wounded. However, as the result of their sacrifice, the 14th Panzer Division suffered heavy losses as well and was not able to take Lutsk.

During the night of June 24-25, elements from the other two divisions of the 22nd Mechanized Corps began to take up their positions alongside the remains of the 19th Tank Division. Fuel shortages were severe, and the Soviet officers partially overcame this problem with a field expedient solution of siphoning fuel from disabled vehicles and distributing it to still operational machines.

Panzers Versus KV-2s

The Soviet units were hardly in shape to fight when the Germans seized the initiative in a dawn attack. In a savage battle that lasted into late afternoon, the Soviet forces disputed every inch of ground. The Germans, steadily grinding down the outgunned light T-26 and BT tanks, came up against a dozen of the monstrous Red Army KV-2 heavy tanks. German shells simply bounced off the thick armor of the KV-2’s ungainly high and boxy turrets. On those few occasions when the KV-2s did manage to bring their 152mm howitzers into play, they were able to temporarily check the German advance.

The best defense the Germans had against these monsters was to wait them out, allowing the Soviet tanks to run out of ammunition and fuel. On one occasion, the crew of a KV-2 tank, its turret ring jammed, out of ammunition and almost out of fuel, drove their vehicle off a steep bank into a river, the driver bailing out at the last moment. More suitable as self-propelled artillery, the small numbers of KV-2s that actually entered the fight did not pose more than a minor local inconvenience to the German panzers.

Germans Grab Lutsk and Dubno, Then Head South

Finally, in fading daylight, and silhouetted by the fires of the burning suburbs around them, the 13th Panzer Division broke into Lutsk after a successful flank attack, forcing the Soviet units to evacuate the city. The desperate fight of the 22nd Mechanized Corps bought valuable time, slowing down two German corps for a day and a half. It also allowed time for the Soviet 9th Mechanized Corps to arrive and deploy in the Rovno area, 65 kilometers east of Lutsk.

At the same time that the Germans continued to exploit the gap breached between the Fifth and Sixth armies, they also advanced south from Lutsk toward the towns of Brody and Dubno, taking Dubno by nightfall. The situation of the Fifth Army was indeed grave. Many of its units found themselves surrounded and fighting for their lives, scattered all the way from the border to Lutsk. The remains of the 22nd Mechanized Corps were streaming in disorder along the highway to Rovno, spreading panic as they went. Only the direct involvement of some of the staff officers from the headquarters of the Fifth Army restored partial order.

Throughout June 26, the Germans attempted to batter their way into Rovno along the Lutsk-Rovno and Dubno-Rovno highways. Unable to do so due to the stubborn resistance of the Fifth Army, they switched their aim south to Rovno, along the secondary roads to the town of Ostrog. The fall of Ostrog would have allowed the Germans to surround the Soviet forces defending Rovno or, at least, force them to pull back.

Throughout June 26, the Germans attempted to batter their way into Rovno along the Lutsk-Rovno and Dubno-Rovno highways. Unable to do so due to the stubborn resistance of the Fifth Army, they switched their aim south to Rovno, along the secondary roads to the town of Ostrog. The fall of Ostrog would have allowed the Germans to surround the Soviet forces defending Rovno or, at least, force them to pull back.

The Soviet 19th Mechanized Corps, under Major General N. V. Feklenko, moved to intercept this new threat and crashed in behind the 11th and 13th Panzer Divisions, which formed the German spearhead. The furious Soviet attack scattered several German supporting units and advanced up to 30 kilometers into German-held territory. In the early afternoon, the Soviet 43rd Tank Division, the vanguard of the attack, fought its way to the eastern outskirts of Dubno. German anti-tank artillery inflicted heavy casualties on the light T-26 tanks, which made up the bulk of the 19th Mechanized Corps.

With impressive tactical handling, the German commanders reacted to this new threat and counterattacked the two dangerously overextended Soviet tank divisions. Caught between the anvil of two German infantry divisions and the hammer of two panzer divisions, Major General Feklenko ordered his corps to pull back to its starting positions in the vicinity of Rovno. By nightfall the fighting had died down, and Dubno remained firmly in German hands.

The T-34 Medium and KV-1 Heavy Tanks Surprise the Germans

While the fighting raged around Dubno, two more Soviet mechanized corps, the 8th and 15th, joined the fray. These two strong corps attacked from Brody, advanced 35 kilometers and cut German lines of communication around the small town of Berestechko, 45 kilometers west of Dubno. For a short time a real possibility existed of encircling the Germans around Dubno.

The 8th and 15th Mechanized Corps were the strongest encountered by the Germans thus far. Even after losses to air attacks and mechanical failures, these two corps still contained approximately 1,500 tanks between them. More significantly, these Soviet formations included approximately 250 new T-34 medium and KV-1 heavy tanks. Unfortunately for the Soviets, the T-34s and KV-1s were not concentrated into large formations. Rather, they were dispersed in small units throughout the two corps.

The appearance of T-34s and KV-1s took the Germans by complete surprise. The German tankers quickly found that their new adversaries were in many ways more than a match for the panzers.

The majority of German field artillery pieces proved only marginally effective in countering these tanks. However, the 88mm antiaircraft cannon, acting in a direct-fire anti-tank role, proved very effective.

German Tactics Pay Off

The German panzer commanders had to quickly improvise new tactics in dealing with superior Soviet tanks. Utilizing their superior tactical proficiency and the higher training levels of their drivers, the German panzers would maneuver out of the way of T-34s and KV-1s, all the while whittling away at lighter BT-5/7s and T-26s. The German field artillery, taking advantage of its greater mobility, would act in a close-support role and soak up the attack of the Soviet tanks. The Germans PzKpfw IIIs and IVs, after dealing with the lighter Soviet tanks, would circle back and attack the T-34s and KV-1s from their more vulnerable sides and rear.

The higher German rate of fire was a significant contributing factor which allowed the Germans to successfully counteract superior Soviet tanks. For every round managed by the Soviet tankers, the Germans could usually respond with two to four rounds in return. The sheer volume of fire would often result in hits on vulnerable areas like gun barrels, turret rings and tracks. Immobilized due to combat damage, mechanical failure or difficult terrain, the Soviet tanks would then succumb to a barrage of fire. German combat engineers displayed significant courage in approaching the immobile but still firing Soviet tanks and destroying them with satchel charges.

The higher German rate of fire was a significant contributing factor which allowed the Germans to successfully counteract superior Soviet tanks. For every round managed by the Soviet tankers, the Germans could usually respond with two to four rounds in return. The sheer volume of fire would often result in hits on vulnerable areas like gun barrels, turret rings and tracks. Immobilized due to combat damage, mechanical failure or difficult terrain, the Soviet tanks would then succumb to a barrage of fire. German combat engineers displayed significant courage in approaching the immobile but still firing Soviet tanks and destroying them with satchel charges.

Often, the inexperienced Soviet drivers moved along the most easily negotiated routes, even if that meant exposing their tanks to greater enemy fire. For example, many of them would guide their vehicles along the tops of ridges or hills, presenting large silhouettes to German gunners.

The behavior of Soviet crews in combat was extremely uneven as well. On some occasions, they would abandon the fight or bail out of their vehicles at the slightest setback. On other occasions, the Soviet soldiers would fight with fatalistic determination even when the tactical situation did not dictate it and when nothing would be gained by their sacrifice.

The lack of radio communications among the Soviet tank forces was a major factor of their relatively poor performance and higher casualties. Below the battalion level, very few Soviet tanks had radios. Motorcycle drivers were used to carry messages over distances longer than the line of sight, while Soviet tank company and platoon commanders had to resort to hand and flag signals. This resulted in a tendency for Soviet tanks to bunch up close to their leaders so as to see and follow their signals. After losing their leaders, the Soviet crews, who were not trained or encouraged to display tactical initiative, were much easier prey for the skilled German tankers

The Ineffective T-35s

Mixed in among the Soviet armor, 41 monstrous T-35 heavy tanks rumbled toward the Germans. Mounting five turrets, manned by a crew of 10, too heavy and too slow, these obsolete tanks suffered multiple mechanical breakdowns or became otherwise immobilized before ever coming to grips with the enemy.

In early July, an after-action report forwarded to the headquarters of the Southwestern Front by the staff of the 8th Mechanized Corps stated that all 45 of its T-35 tanks were lost. Four machines had been abandoned when the advancing Germans overran the 8th Corps bases, 32 suffered mechanical breakdowns, and two were destroyed by the German air attacks during the approach to battle. Only seven T-35s actually entered the fight, and all of these were destroyed by the enemy. Since the Soviet forces were virtually without any means to retrieve and evacuate the disabled combat vehicles, all the T-35s were lost.

The Battle for Berestechko: A Fire-Breathing Nightmare

The battle around Berestechko turned into a grinding, fire-breathing nightmare that chewed up men and machines on both sides. German aircraft pounded the Soviet positions without let up. In one attack they succeeded in wounding Major General Karpezo, commander of the 15th Mechanized Corps, at his command post.

In his war diary, the Chief of German Army General Staff, General Franz Halder, noted: “ … the heavy fighting continues on the right flank of Panzer Group 1. The Russian 8th Tank Corps achieved deep penetration of our positions … this caused major disorder in our rear echelons in the area between Brody and Dubno. Dubno is threatened from the south-west … ”

Even though they were causing severe problems for the Germans, the two Soviet armored formations were exhausting themselves. The attrition of men, machines and equipment was reaching alarming proportions. Despite Lieutenant General Kirponos’ pleas to pull his forces back for rest and reinforcement, Stavka, the Soviet High Command, ordered him to continue the offensive.

On the morning of June 28, the Germans launched a counter-offensive of their own against the depleted Soviet formations. German reconnaissance was able to find the exposed left flank of the 8th Mechanized Corps, and a four-division attack began to roll up the Soviet units. By afternoon, each of the three divisions of the 8th Mechanized Corps found itself surrounded. They received orders to fight their way out and two were able to do so. The third however, the 34th Tank Division, was completely destroyed, losing all of its tanks and other vehicles. Its commander, Colonel I.V. Vasilyev, was killed as well. Only about 1,000 men led by the commissar of the 8th Mechanized Corps, N.K. Popel, fought their way out. During the day’s fighting the corps lost over 10,000 men and 96 tanks, as well as over half its artillery.

The 15th Mechanized Corps was taking severe casualties as well, and during the night of June 29, both corps were finally permitted to retreat south of Brody. The Soviet formations began to fight desperate rearguard actions, trying to disengage from the enemy. On the evening of the 30th, German aircraft conducted a major attack on Soviet mechanized columns retreating in the direction of Zolochev and turned the highway around the city into a huge funeral pyre of vehicles.

Rokossovksi Attempts to Stem the Retreat

At the same time, that the 8th and 15th Corps were entering the fight, the 9th Mechanized Corps was finally able to concentrate for its own attack on Dubno. Coming up on line, its commander, Major General K. K. Rokossovksi, a future marshal of the Soviet Union, observed large numbers of Red Army soldiers aimlessly wondering around the woods. He quickly detailed several of his staff officers to round up the stragglers, arm them as best as they could, and put them back into ranks.

To his dismay, Rokossovski found several high-ranking officers trying to hide among the stragglers. In his memoirs, Rokossovski wrote that he was severely tempted to shoot one “panic-monger,” a colonel with whom he had a heated conversation. Tough-as-nails Rokossovksi, a survivor of Stalin’s prewar purges of the military officer corps, allowed the colonel to redeem himself and lead a makeshift unit into combat. In the morning of June 27, it was Rokossovski’s turn to launch his corps, numbering only 200 light tanks, into action against Dubno. The 9th Mechanized Corps met heavy resistance right away, and the Germans began to probe around its unprotected flanks and infiltrate the gaps between its units, threatening to surround the corps.

To his dismay, Rokossovski found several high-ranking officers trying to hide among the stragglers. In his memoirs, Rokossovski wrote that he was severely tempted to shoot one “panic-monger,” a colonel with whom he had a heated conversation. Tough-as-nails Rokossovksi, a survivor of Stalin’s prewar purges of the military officer corps, allowed the colonel to redeem himself and lead a makeshift unit into combat. In the morning of June 27, it was Rokossovski’s turn to launch his corps, numbering only 200 light tanks, into action against Dubno. The 9th Mechanized Corps met heavy resistance right away, and the Germans began to probe around its unprotected flanks and infiltrate the gaps between its units, threatening to surround the corps.

Like the commander of the 19th Mechanized Corps the previous day, Rokossovski was forced to order a retreat by nightfall without achieving his objective. His attack, however, delayed the German advance and relieved pressure on the 19th Mechanized Corps, which was retreating in the direction of Rovno.

Together with mauled infantry formations of the Fifth Army, the two mechanized corps continued to stubbornly defend Rovno for another day despite the best German efforts to take the city. Their valiant stand was in vain. On the evening of June 28, the German 11th Panzer Division captured the city of Ostrog and established a bridgehead across the Goryn River. The Soviet forces defending Rovno were suddenly threatened with an unpleasant possibility of being left on the wrong side of the river, with German units breaking into their rear echelons. Reluctantly, the Soviet forces abandoned Rovno and pulled back across the river to take up defensive positions in the Tuchin–Goschi area.

How the “Bloody Triangle” Came to an End

With the fall of Ostrog, the battle of the “Bloody Triangle” was effectively over. The battered Soviet formations managed to hold the line at the Goryn River until July 2, before finally being forced further back.

On July 7, the five Soviet mechanized corps that participated in fighting in the “Bloody Triangle” mustered 679 tanks out of a pre-war strength of 3,140. The Soviet Fifth Army, though bled white, was not defeated, and the majority of its combat formations, although having suffered appalling casualties, were not destroyed. The Fifth Army, clinging to the southern edge of the Pripyat Marshes, continued to pose a threat to the left flank and rear of the German advance on Kiev, capital city of the Ukraine. It constituted such a major thorn in the German side that Adolf Hitler specifically called for its annihilation in his Directive No. 33, dated July 19, 1941.

After the fall of Kiev in September, the Fifth Army was finally destroyed and its commander, Major General Potapov, taken prisoner. He did manage to survive the war in a POW camp. Lieutenant General Kirponos, who so valiantly tried to shore up his crumbling Southwestern Front, was killed trying to break out of the same encirclement. General Rokossovski came back through the same area in 1944, only this time his victorious T-34s were pushing the exhausted enemy troops westward toward Germany.

What was the reasoning of the Soviet High Command for so promiscuously using up five mechanized corps? Did the generals not realize the severity of the situation and futility of holding the forward positions? It is possible that the Soviet High Command, relying on incomplete or false information, was under the impression that this was not a major invasion but a border provocation. After all, the Soviet Union had fought two border conflicts against Japan in the late 1930s without either of them expanding into a full-scale war.

Perhaps the Soviet leadership realized the severity of the situation all too well, buying time to conduct full mobilization. Every day that the frontline echelons bought with their blood allowed reserves to be formed, armed and sent into battle.

Perhaps the truth, as it is prone to do, lies somewhere in between. Either way, the tank battles in the “Bloody Triangle” demonstrated to the Germans that the Soviet Union was not a “giant with the feet of clay” after all. Even though the Fifth Army and the five Soviet mechanized corps did not accomplish their mission of destroying the German mobile group, they managed to slow the German offensive for nine days.

This delay, from June 24 to July 2, significantly disrupted the German timetable of operations in the Ukraine. After easy German victories in Western Europe, the tenacity of the Soviet soldiers and their willingness to dispute every inch of ground came as unpleasant surprise. A long and painful struggle loomed ahead.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments