By Robert Suhr

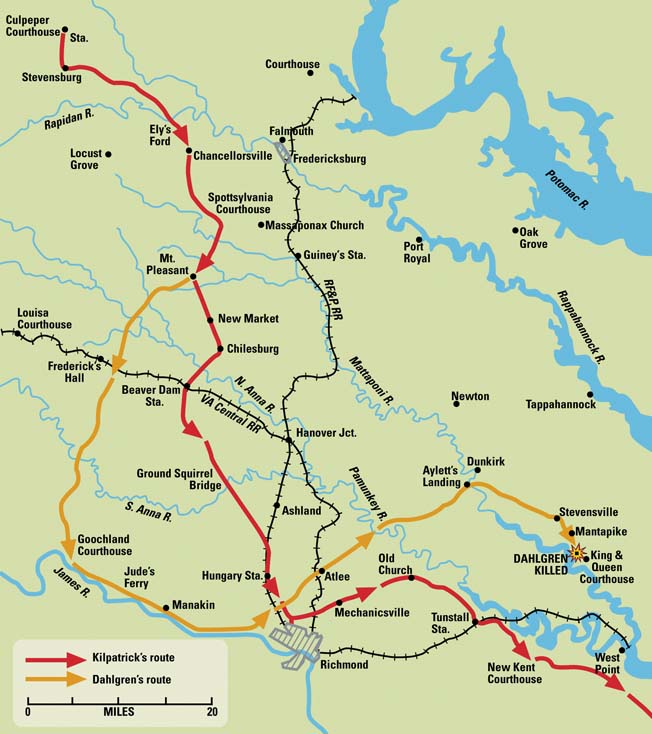

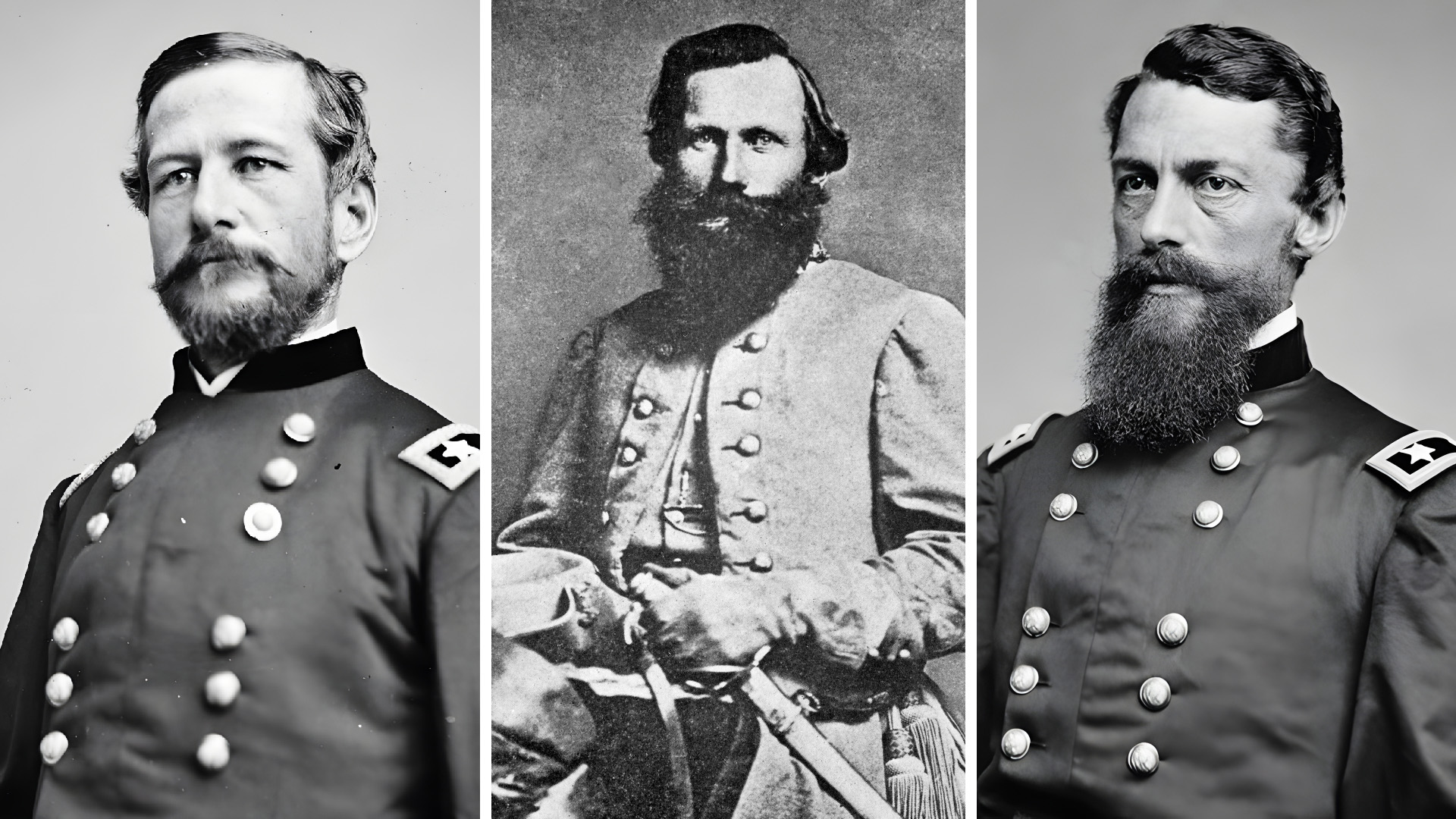

On the night of February 28, 1864, an advanced unit of bluecoat troopers captured two guards at the Rapidan River ford, and the remainder in a house near the river. Soon to follow were the first four hundred raiders under the command of Col. Ulric Dahlgren. Not far behind was the main force of 3,500 men under Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick. The Union Army’s largest and most adventurous cavalry raid since Chancellorsville was underway.

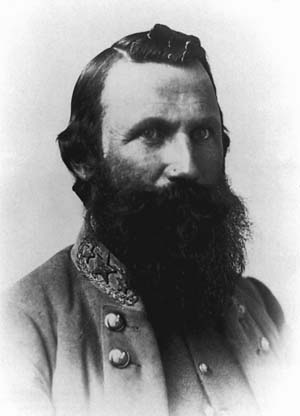

What became known as the “Kilpatrick-Dahlgren Raid” sprang from the fertile mind of Judson Kilpatrick, one of the Army of the Potomac’s “boy generals.” Kilpatrick’s men, in fact, had little respect for him. One officer later wrote: “In a few days he had fairly earned the sobriquet ‘Kill Cavalry.’ This was not because men were killed under his command, but for the reason that so many lives were sacrificed by him for no good purpose whatever.”

Five days after his promotion to general, Kilpatrick ordered the 1st Vermont Cavalry to charge the right of Longstreet’s line at Gettysburg. It was senseless and caused the death of Brig. Gen. Elon Farnsworth. A week-and-a-half later, Kilpatrick ordered 60 men from the 6th Michigan to make a suicidal charge on a division of infantry. Even Maj. Gen. William Sherman, who wanted him to command his cavalry, thought he was a “danged fool.”

A Savvy Fool

But Kilpatrick knew the politics involved in running the Army of the Potomac. In early 1864, he spread word that a raid on Richmond would succeed, and that he was willing to lead it. On February 11, Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick, temporarily commanding the Army of the Potomac, ordered Kilpatrick to “report to the President, as requested by the latter.”

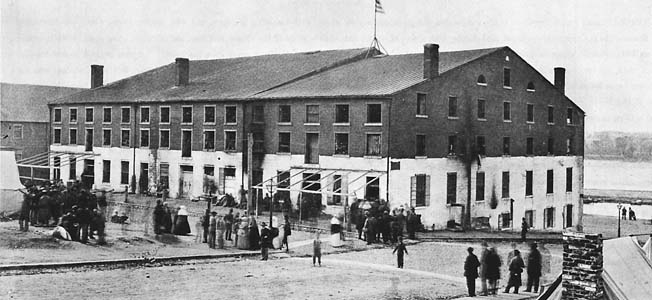

Lincoln, as Kilpatrick had hoped, had caught word of the idea and wanted to hear more. The President had several reasons for favoring a raid on the Confederate capital. He wanted an amnesty proclamation spread throughout northern Virginia. In addition, escaped prisoners from Libby Prison in Richmond generated an outcry in the Northern press against prison conditions. Lastly, Federal spies reported few troops guarding the Confederate capital, making it a target too tempting to ignore.

The President and the young cavalry leader met in Washington on Lincoln’s birthday. After their meeting, Kilpatrick drew up a plan in which he proposed to raid Richmond with four thousand men. In route, he would destroy railroad bridges and stations while distributing Lincoln’s amnesty proclamation. Once in Richmond, he would free the Union prisoners and arrest Jefferson Davis. He gave himself the option of returning the way he had come, or riding toward Union positions on the Peninsula, between the York and James rivers.

The prospects for success were good because the Confederates had few cavalry to oppose a raid. Robert E. Lee had granted furloughs to many men so they could go home to garner new horses. In addition, there was little food for the existing mounts, forcing Lee to order the artillery to concentrate along the railroads to make it easier to bring forage to the horses.

Kilpatrick Assembles his Allies

Still, to be successful, Kilpatrick needed surprise, and that he would fane get. Proof appeared in the person of Col. Ulric Dahlgren, son of the prominent rear admiral, and lately returned to active duty since losing a leg during the Gettysburg campaign. Once catching wind of the raid in Washington, he visited Kilpatrick to ask to come along. Kilpatrick quickly included the young colonel in his plan. While he attacked Richmond from the north, Dahlgren would cross the James River to storm it from the southwest.

By crossing the Rapidan at Ely’s Ford, Kilpatrick would pass around the Confederate right. To draw attention away from that flank, Brig. Gen. George Custer was ordered to demonstrate on the Confederate left. Custer was given 1,500 troopers and a section of artillery. (Also along to record this raid was artist Alfred Waud.)

On the 27th, Sedgwick’s VI Corps began the diversion on the Confederate left by advancing west to Robertson’s River. The next day Custer moved up to join the infantry.

Knowing Sedgwick had participated in the council of war that had planned this operation, Custer stopped to express concerns about his role.

Custer’s Concerns

Custer’s objective was the railroad bridge over the Rivanna River near Charlottesville. By destroying it, he could keep supplies from reaching the Confederate Army from the Shenandoah Valley and western Virginia.

Custer had orders to ride to the Shenandoah if the Confederates cut off his line of retreat, but he had heard there were five thousand Confederate troopers in the valley. He was afraid the army intended to sacrifice his command so Kilpatrick’s raid would succeed.

After Custer listed his concerns, Sedgwick assured him that they had considered it all. Custer replied, “Well, then, I may have to do one of two things: either strike boldly across Lee’s rear and try to reach Kilpatrick, or else start with all the men I can keep together and try to join Sherman in the south-west.”

A Disturbing Rumor

In any event, about 2 am on February 29, Custer’s command crossed Robertson’s River at Banks’ Mill Ford and rode south toward Standardsville. The movement of the Union cavalry did not go unnoticed. Shadowing the column was Lt. J.N. Cunningham of the 1st Virginia Cavalry.

To keep word of the raiding party from spreading, the Union troopers seized all men they encountered. From them, Custer heard the disturbing rumor that Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry division was bivouacked near Charlottesville to recruit men and gather forage for the horses.

Indeed, as soon as Maj. Gen. Jeb Stuart heard Union cavalry had crossed the Rapidan, he rode to Brig. Gen. William Wickham’s headquarters at Montpelier. He found only part of the brigade in bivouac, because many men had not returned from their furloughs. With most of the 1st Virginia Cavalry on picket duty, Wickham had only the 2nd Virginia and Company K of the 1st, about four hundred men in all. Assuming Custer’s objective was Charlottesville, Stuart led the brigade in that direction.

When he reached the Rivanna River, Custer sent one squadron of the 1st U.S. Cavalry up the river, and one of the 5th Cavalry down it. This latter force under Capt. Joseph Ash rode directly into the camp of Stuart’s Horse Artillery.

Stuart, in fact, had four batteries under the command of Capt. Marcellus Moorman in bivouac a couple of miles from Charlottesville. The Confederate artillery park was practically defenseless. Not only did it lack cavalry or infantry support, but the cannoneers had no muskets and only a few pistols.

Moorman’s Gambit

Lieutenant Cunningham provided Moorman with a few minutes’ warning, but Moorman knew he was going to have trouble saving his guns. He could not fight, but neither could he flee with his horses running loose in a field.

To gain time for his men to remove the guns, he used a ruse to make Ash think a large force protected them. He mounted some troops to give the impression cavalry supported his guns. Most of his men paraded to the flank as he yelled, “Tell Colonel Delany to bring up the 7th Regiment.” He placed cannoneers with pistols in front of the guns to pose as a skirmish line.

As the Union cavalry advanced, the Confederate cannon opened fire. Some Union troops got in among the artillery huts while Ash’s main force drove back the “skirmishers.” Still, according to Moorman, Union aggressiveness ended when the two groups of Union troopers began firing at each other.

All the while, Confederate soldiers sought their horses. But they managed to hitch them to, and drag away, only four cannon by the time Ash ordered his men to withdraw.

A Not So Clever Diversion

Custer turned out to be his own worst enemy. Expecting to find a considerable force of infantry, he believed he had found it. Ash reported that he saw Wickham’s bivouac only three hundred yards from Moorman’s camp. In the distance Custer heard the sounds of train whistles, which he took to mean the arrival of Confederate reinforcements. He ordered his command to withdraw.

Custer did not destroy the bridge at Charlottesville or capture a significant part of Stuart’s Horse Artillery; however, he was completely successful in his primary mission, that of providing a diversion for Kilpatrick. Not only did he draw some Confederate cavalry after him, he caused Jeb Stuart to take personal command of the pursuit. That kept Stuart from interfering with Kilpatrick.

Meanwhile Stuart first learned from distant gunfire that the Federals had reached Charlottesville, then that they were withdrawing. So he changed direction to try to cut off their retreat. But the weather deteriorated, turning from rain to snow and finally to sleet as Stuart rode across country to get in front of the Union cavalry.

Custer’s command now rode in two groups. Five hundred men under Col. William Stedman were in front while the remaining thousand under Custer’s direct command rode some distance behind.

About 9 pm, eight miles from Standardsville, Custer stopped to let the artillery horses rest and feed. When he halted, Custer sent several couriers after Stedman, but they did not find him.

Thus Stedman continued forward through the night. Beyond Standardsville, the road forked, one branch leading back toward Banks’ Mill Ford and the other toward Burton’s Ford. Custer intended to recross Robertson’s River at Burton’s Ford, but when Stedman reached the fork he took the wrong branch, crossing the river at Banks’ Mill Ford.

When Custer started forward again, a guide led the column down a deep, muddy ravine. The cavalry had to halt when the guns could no longer move forward. Back on the main road at 4 am, Custer decided to bivouac for the rest of the night.

A Surprise for Custer?

When Stuart reached the road, he learned that one Union force had already passed, but another was coming. He led Wickham’s Brigade down the road toward Banks’ Mill Ford, putting his men behind a rail fence next to the road. Hoping to take Custer by surprise, he ordered the men to remain silent.

When Stuart reached the road, he learned that one Union force had already passed, but another was coming. He led Wickham’s Brigade down the road toward Banks’ Mill Ford, putting his men behind a rail fence next to the road. Hoping to take Custer by surprise, he ordered the men to remain silent.

Ash commanded Custer’s advance. When he reached the fork in the road, he followed Stedman’s tracks toward Banks’ Mill Ford. Almost immediately, Stuart’s advance attacked, thinking it was Stedman’s rear guard.

Ash fell back on the rest of the 5th Cavalry. Captain Abraham Arnold led a counterattack that routed the Confederates. From the prisoners, Custer knew what unit he faced, and who led it.

He hid the bulk of his command in a ravine while his two guns deployed on a ridge. The artillery pounded the Confederate cavalry before he charged with his thousand troopers. Stuart’s outnumbered command crumbled under the attack and fell back toward the ford. Nevertheless Stuart deployed to meet charge after charge.

Custer pressed the attack, driving the Confederate cavalry before him. But after two miles he realized that he was on the wrong road—he was riding toward the wrong ford.

So Custer deployed as though he intended to batter his way through the Confederate lines to the ford. But behind him, he had the cannon withdraw at a trot. When he had waited as long as he could without arousing Confederate suspicions, he swung his columns about and raced back down the road.

Stuart tried to follow, but his exhausted men and horses could not keep up. Before long, he stopped the pursuit.

Secrets Between Allies

About the time Custer withdrew from Charlottesville, Kilpatrick was meeting with Dahlgren and exchanging notes that would cast a pall over the raid ever after. Dahlgren showed Kilpatrick a copy of an address he wanted to read to his troops. The general read it, found it acceptable, and marked “approved” on it in red ink before signing his name.

Unknown to Kilpatrick, Dahlgren had another copy of the speech, one with significant changes.

Then they were off. To begin, both Dahlgren and Kilpatrick started on the same route south. But at Mt. Pleasant, just south of Spotsylvania Courthouse, as agreed Dahlgren turned west while Kilpatrick continued south.

“Twenty Wooden Buildings Were At Once Set On Fire…”

At about 4 pm on the 29th, just when a cold rain began to fall, Kilpatrick approached Beaver Dam Station on the Virginia Central Railroad. Wanting to take the station by surprise, Kilpatrick sent a small party ahead to capture the telegraph operator to keep him from spreading the alarm. They succeeded and the troopers then went to work destroying the station. They ripped up track and tore down telegraph lines.

One officer described the scene in his report: “Twenty wooden buildings were at once set on fire, forming one sheet of flame, rising high above the surrounding woods, and the black forms of our soldiers jumping around it seemed from a distance like demons on some hellish sport.”

Fortune for the Confederates

Ironically the burning buildings saved a Confederate train from capture. Alarmed by the fires ahead, the engineer stopped the train and sent a guard down the tracks to investigate and report. Thus warned to the presence of the raiding party, the engineer backed the train out of danger.

This was not the only piece of good luck for the Confederates that day. Also on the 29th, just as Dahlgren’s force approached Fredericks’ Hall Station, a train passed through carrying Robert E. Lee back to his headquarters from a meeting with Jefferson Davis. His capture would have been a serious blow indeed to the Southern cause.

In any event, when Dahlgren reached the station, the Confederates presented him with an opportunity to hurt their artillery even greater than the one provided Custer at Charlottesville.

The Confederates had 82 guns assigned to the II Corps in bivouac at Fredericks’ Hall Station. The Confederates had left these guns almost as unprotected as they had the Horse Artillery.

During the winter, Brig. Gen. Armistead Long, commanding the II Corps artillery, was afraid a situation such as this might arise. In order that the cannoneers might put up some semblance of a defense, Long requisitioned 125 infantry muskets that he distributed among four batteries. During the cold winter months, troops from these four batteries trained as infantry.

At 3 pm, Dahlgren was within striking distance of the Confederate bivouac. One mile from the station, he asked a slave if there was infantry ahead of them. When he replied “yes,” Dahlgren asked him how he knew. He had recognized the infantry muskets by their bayonets. He told Dahlgren that the troops ahead of him had “stickers” on the ends of their rifles.

Dahlgren’s Consolation Prize

Part of Dahlgren’s force was within three hundred yards of the Confederate guns when ordered to withdraw. But to do so they had to pass around a hill. From the amount of activity on it, they thought the Confederates had a battery up there. To salvage something from the effort, the troopers from the 5th New York Cavalry decided to storm the hill.

To their surprise, instead of capturing a battery, they captured a court-martial panel. They took the officers with them as prisoners, but most escaped during the night. (Those who escaped thought Dahlgren allowed them to escape because they were slowing down his column.)

Late on the 29th, Hampton moved to intercept Kilpatrick. Hampton had only 253 troopers of the 1st North Carolina Cavalry and 53 from the 2nd, because most of his command had not returned from their furloughs in North Carolina. And most of the guns were still near Charlottesville, so he had only one section of artillery. Nevertheless, Hampton ordered these two skeleton regiments and two guns to ride to Mount Carmel Church.

Just before midnight, Robert E. Lee notified Brig. Gen. Bradley Johnson, commanding the Maryland Line on the Confederate right flank, that Union cavalry had ridden in his direction. When scouts reported Kilpatrick moving toward Hanover Junction, Bradley started in that direction with all the men available in his command, 60 troopers of the 1st Maryland Cavalry.

About an hour after midnight on the 30th, Kilpatrick quit Beaver Dam Station, blundering about the countryside in the dark. He intended to cross the South Anna River at Ground Squirrel Bridge, but a guide led him toward Ashland where the advance ran into Confederate pickets. He divided his force there, sending Maj. William Hall forward with his 450 troopers to burn the railroad bridge over the South Anna at Taylorsville. This move not only would destroy part of Lee’s supply line, it would help protect Kilpatrick’s rear.

After sunup, Wade Hampton led his command from Mount Carmel Church to Hanover Courthouse. Finding no enemy there, he rode on toward Hughes’ Crossroads.

When he heard of the approach of a Union raiding party, Col. Walter H. Stevens, commanding Richmond’s defenses, deployed the few troops he had. He ordered his division commanders to double the number of guards at strategic locations.

Torpedos, Turpentine, and Oakum

About 10 in the morning, the van of Brig. Gen. Henry Davies’s Brigade of bluecoat troopers crossed the Chickahominy and turned down the Brook Turnpike. Civilians there told him no one expected his raid. Thus believing he had achieved surprise on the Confederate capital, he continued forward.

Meanwhile, through the early morning, Dahlgren rode toward the James River. He stopped for a few minutes at the James River and Kawanwha Canal, 21 miles from Richmond. There, he divided his force, sending a hundred troopers with Capt. John Mitchell down the canal with prisoners and ambulances. Dahlgren gave Mitchell a box of “torpedoes” (i.e., mines), some turpentine and oakum. He ordered Mitchell to rejoin him at Mayo Bridge. If he could not, he was to go to Hungary Station where Dahlgren thought Kilpatrick was.

The False Traitor

To help him cross the James River, Dahlgren had as a guide a free black bricklayer named Martin Robinson. Robinson had entered Union lines with several Union officers who had escaped from Libby Prison just a few weeks before. Born near Dover Mills on the James River, he claimed to know a ford near Jude’s Ferry.

As they approached the place where Robinson said there was a ford, Dahlgren saw a sloop going down the river. This showed him that the river was not fordable there. Believing Robinson had been traitorous, Dahlgren forthwith hanged him from a nearby tree. (Apparently, it did not occur to Dahlgren that two days of heavy rain might have caused the river to flood, as was indeed the case.)

Unable to cross, Dahlgren continued toward Richmond on the western pike. Mitchell took about 80 troopers along the canal while the remainder of his command moved down the river road. Mitchell destroyed six grist mills, six canal boats, a coal works and a lock before he learned there was nothing else until Three Mile Lock near Richmond. Because the ambulances could not travel on the tow-path that ran parallel to the canal, Mitchell moved over to the river road. Expecting Dahlgren to be on the far side of the river, the tracks on the road surprised him. A little farther on, he found Robinson’s body hanging from a tree. He paused long enough to bury it before pressing on.

Around 3 pm, Dahlgren halted to let his horses rest and feed at Short Pump, a crossroads seven miles from Richmond. At 3:30, Mitchell arrived with the rest of his command.

An ‘Intimidating’ Force Appears

Meanwhile, to the north, Confederate Bradley Johnson brushed past Hall’s command of Kilpatrick’s force near Taylorsville. At Yellow Tavern, he captured a straggler who told him about Hall. Realizing he was now between two large Union forces, he moved off the road but left pickets on the road in Union uniform. In a few minutes they captured an officer and four guards. The officer was carrying a verbal message from Dahlgren to Kilpatrick that Johnson “forced” him to tell. From him, he learned Dahlgren had not crossed the river, but would attack down the river road at dark. The interception of this message kept Kilpatrick from knowing about Dahlgren’s position or movements.

Meanwhile, to the north, Confederate Bradley Johnson brushed past Hall’s command of Kilpatrick’s force near Taylorsville. At Yellow Tavern, he captured a straggler who told him about Hall. Realizing he was now between two large Union forces, he moved off the road but left pickets on the road in Union uniform. In a few minutes they captured an officer and four guards. The officer was carrying a verbal message from Dahlgren to Kilpatrick that Johnson “forced” him to tell. From him, he learned Dahlgren had not crossed the river, but would attack down the river road at dark. The interception of this message kept Kilpatrick from knowing about Dahlgren’s position or movements.

One mile from Richmond, Kilpatrick’s advance came to a halt when it ran into the Confederate defenses that Kilpatrick described as a “considerable force of infantry with artillery.” Kilpatrick ordered Brig. Gen. Henry Davies to attack with his brigade.

What Davies saw of the Confederate defenses intimidated him. He could not make a mounted charge because the fields were muddy and crossed with deep, wide ditches. The troops would have to attack on foot across a thousand yards of open ground. He put five hundred troops on the left and ordered the rest of the brigade to advance, but before the attack began, Kilpatrick ordered a retreat.

Kilpatrick later claimed he decided to withdraw “when I discovered that the enemy was rapidly receiving re-enforcements, not only of infantry but artillery.” In addition, he believed that without Dahlgren’s support his attack would end in a “bloody failure.”

Kilpatrick instead ordered Davies to cover the rear of the division as it retreated northeast toward the Meadows bridges over the Chickahominy River. The Union troopers fell back believing a strong enemy force was in pursuit. One officer reported seeing a “considerable force of infantry” behind him.

Failure at Every Turn

As Kilpatrick rode north, he heard more news of failure. En route to the Meadows bridges, Major Hall rejoined him with the news that he had found the railroad bridge over the South Anna River too well guarded to attack.

Once the rear guard had crossed the Chickahominy, Union troopers destroyed the wagon bridge, and the railroad bridge one mile downstream. Not far beyond the river, late on March 1, Kilpatrick went into bivouac near Mechanicsville.

Dahlgren knew about Kilpatrick’s failure to take Richmond. Throughout the morning he had heard the sounds of Kilpatrick’s cannon and later learned from prisoners that Kilpatrick had made the effort but then retreated. Dahlgren’s signal officer fired some rockets, but because of the inclement weather they were not seen.

Nevertheless, Dahlgren decided to make an attack on Richmond, not so much in the hope of achieving the raid’s objectives as in gaining information for a future raid. Like Kilpatrick, Dahlgren believed the sound of train whistles near Richmond meant the Confederates were rushing reinforcements from the south. He sent the ambulances and prisoners to Hungary Station, where he thought they might find Kilpatrick.

The Confederates had only a small picket on the plank road at the outer line west of the city. Dahlgren pushed through it without much trouble at 5 pm. But at the second line, about five miles from Richmond, the Confederates fired a heavy volley that brought Dahlgren’s advance to a halt. The colonel ordered the troops to dismount and advance on foot through the woods beside the road, but no one could make headway. Finally a detachment of the 1st Maine Cavalry broke through.

Then, at the edge of Richmond, Dahlgren found a new Confederate line. So far Dahlgren’s troops had been fighting the Armory Battalion of the Richmond militia. As they came nearer the city, a battalion of government clerks reinforced them.

Retreat From the Confederate Capital

The Union troopers then began to fall back despite Dahlgren’s efforts to rally them. Ultimately, he ordered the entire command to retreat.

Thus Dahlgren abandoned efforts to break into the Confederate capital. After ordering Captain Mitchell to command the rear guard, he moved to the head of the column. He left his wounded behind in the care of an assistant surgeon, because they would otherwise slow down his retreat.

Escape Through the Shadows

Dahlgren’s immediate goal was Hungary Station where he hoped to find Kilpatrick. At first there was no opposition from the Confederates, and it was a leisurely withdrawal. In fact, the Confederates may not have harassed the bluecoats because they might not have been able to find them in the dark.

Every time the column ahead of him stopped, Mitchell deployed his troops in case the Confederates attacked. Once, the column halted at the intersection with the plank road and did not start forward again. Mitchell knew the longer they paused, the greater the risk the Confederates would catch up to and attack them. Finally he sent a lieutenant ahead to find out what the delay was. The man soon reported back that Dahlgren, Maj. Edwin Cooke and about a hundred troops had disappeared into the dark.

Mitchell talked with the other officers before deciding to go toward Hungary Station. A row of campfires blocked his route. He mounted a charge, but heavy rifle fire drove it back. Next Mitchell sent scouts toward Hungary Station and released his prisoners. Then he decided to wait until morning. Twice during the night Mitchell heard the sounds of large parties of Confederates marching past, but no one discovered his troops.

When Dahlgren reached Hungary Station, he discovered two things. First he learned that Mitchell and most of his command were no longer behind him. The other news was no better. A slave told him Kilpatrick had gone down the peninsula. Dahlgren decided he could not catch up with him so would head for Glouchester Point to join Union troops there.

Another Round in Richmond

Although deep in enemy territory, Kilpatrick placed guards only on the roads. He ordered Lt. Col. Allyne Litchfield to “have your men make fires, get coffee, and make themselves comfortable and put a picket of ten men at the railroad crossing.”

At sundown, Hampton arrived at Hughes’ Crossroads. In the distance he saw Kilpatrick’s fires between Atlee’s Station and Richmond. He rode to the station where he set up headquarters in the ticket office. In a snowstorm, a scouting party advanced toward the fires to see if they were Union or Confederate. When they drew fire from the Union pickets, he ordered them to fall back. Hampton then dismounted a hundred troopers to attack as skirmishers while the others remained on horseback as support.

Around 9 pm, Litchfield learned his pickets were exchanging shots with Confederates. He deployed his regiment along the road, and sent word of the attack. He received new orders to double the size of his picket force, but he doubted 20 men would do any better than 10. Then, while checking on his left flank, Litchfield was captured.

Near the end of the day, Kilpatrick decided to make another attack on Richmond. Scouts reported the Confederate defenses concentrated on the Brook Turnpike and the plank road. Only two pickets guarded the road from Mechanicsville to Richmond. Kilpatrick decided to take advantage of the Confederate deployment with one more attack. At about 10:30, he summoned Lt. Col. Addison Preston of the 1st Vermont Cavalry and Maj. Constantine Taylor of the 1st Maine Cavalry. Each would lead a column of five hundred troopers into Richmond. One column would go to Libby Prison to free the prisoners there; the other would search for Jefferson Davis.

Some Plans Are Not Meant To Be

While Kilpatrick met with his officers, a courier arrived with news that the Confederates were firing on his pickets. A second message arrived minutes later that Confederates were overrunning his position. Not knowing the size of the force attacking him, Kilpatrick abandoned any thoughts of attacking Richmond and ordered a retreat in the direction of Old Church.

On the morning of the 2nd, Robert E. Lee tried to trap Kilpatrick. He ordered Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson to move most of his division into the Wilderness to cut Kilpatrick’s line of retreat back to the Army of the Potomac.

Kilpatrick was already beyond Lee’s reach, however. At 1 pm he decided to go to the Union positions on the peninsula by the shortest route. His men were exhausted, and prisoners told him Hampton was at Hanover Junction with a “large force” of mounted infantry.

Kilpatrick went into bivouac at Old Church about four in the morning of March 2. After dawn, he changed positions, moving a mile beyond the town. Bradley Johnson attacked the rear guard with his handful of cavalry. Kilpatrick temporarily drove them off with a charge by a squadron of the 1st Maine Cavalry. But when the Union cavalry withdrew, Johnson closed in behind them again.

Problems Mount for Dahlgren

Because of the darkness, Hampton waited until dawn before pursuing Kilpatrick. His men had ridden far during the previous two days so he stopped at Old Church to let his horses rest. While there he received orders from Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon to attack Kilpatrick at Tunstall’s Station, but by then Kilpatrick had already retreated to Williamsburg.

Because of the darkness, Hampton waited until dawn before pursuing Kilpatrick. His men had ridden far during the previous two days so he stopped at Old Church to let his horses rest. While there he received orders from Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon to attack Kilpatrick at Tunstall’s Station, but by then Kilpatrick had already retreated to Williamsburg.

Meanwhile, Dahlgren’s problems increased. He had trouble crossing the Pamunkey River on the morning of the 2nd—the water was high and the ferry was missing. Ultimately, two men swam across the river to retrieve the ferry, but getting all his men across took several hours.

Lieutenant James Pollard of the 9th Virginia Cavalry led a handful of men after Dahlgren, but also notified Capt. Edward Fox of the 5th Virginia Cavalry that the Union raiders were advancing through King William County. Fox assembled 28 men of his company (the “King and Queen Cavalry”) at King and Queen Courthouse and started after Dahlgren.

As Kilpatrick rode east, the 9th Virginia Cavalry followed. Two miles from Hanover Junction, Col. J.L.T. Beale learned that the main Union force (Kilpatrick’s) was at Old Church, while a smaller force (Dahlgren’s) was at Hanover Courthouse. Beale rode toward the latter, but by then Dahlgren had left. Beale then joined Bradley Johnson at Old Church. At Tunstall Station, he found “half extinct fires of the Yankee camp.”

On the morning of the 2nd, Mitchell reached Hungary Station, but like Dahlgren discovered Kilpatrick had left. He led his troopers down a mountain road to the Louisa Courthouse and Richmond Turnpike. He tried to reach Hanover Courthouse by the plank road but Confederate skirmishers stopped him. Learning that a large enemy force was at Ground Squirrel Bridge, Mitchell crossed the Chickahominy at Rodes’ Mills. About eight miles from Tunstall Station, he found the road blocked by the troops of Bradley Johnson’s Maryland Line. A cavalry charge through the Confederate lines brought the majority of Dahlgren’s command into Kilpatrick’s camp.

Ambushed Beyond the Creek

Beyond the Mattapony River, Pollard learned Dahlgren had taken the right-hand fork—the river road. Citizens convinced him that he could get ahead of the Union raiders below Stevensville. Pollard thus sent a small party to harass the Union rear while he took the rest of the men in an attempt to head off the Union raiders.

Dahlgren played into the hands of his pursuers. After crossing Anseamancok Creek, around 6 pm, he stopped to let his exhausted troops rest and eat. His men found a barn full of corn, their first meal in 36 hours. For three hours the Union cavalry rested before the officers roused them to push on.

Pollard was in front of him by then, and he had reinforcements. Once he had the ambush laid out, Fox arrived with his 28 troopers. Because of his senior rank, Fox took command (though he gave Pollard credit for setting up the ambush).

Dahlgren Narrowly Escapes

Dahlgren’s column stumbled down the road into the Confederate ambush. Soon someone challenged the main column. Accounts differ about the exact words said, but within seconds a volley erupted from hidden Confederates that sent horses and riders to the ground. When Major Cooke returned to the remainder of the column on foot, he discovered Dahlgren was not with them. A trooper sent to look for him returned convinced that Dahlgren had escaped into the bushes.

Cooke led the troopers through a break in the trees to a field. Expecting the Confederates to attack, he deployed his troopers in a line facing the road. Behind them were 100 to 150 runaway slaves who had joined them. The actions of the Union cavalry, though, were only false bravado, since there was little they could have done to stop the Confederates had they advanced—among the 70 troopers in the field there were only 30 cartridges.

The Confederates knew where the Union raiders were and were willing to let them remain there until more troops arrived. Setting up small outposts to keep an eye on them, they waited for dawn.

One unit that had turned out to stop Dahlgren was the local defense company of Capt. Edward Halbach. After the ambush, Halbach’s “school boys” had liberated a prisoner who claimed to be a Confederate lieutenant (which he turned out to be). While waiting for dawn, Halbach moved his boys and their recently freed prisoner into the woods.

Mementos From a Dead Man With a Wooden Leg

While they waited, one of his students, William Littlepage, asked if Halbach wanted a cigar. When Halbach asked where he had gotten it, the boy told his chief how he had found it on the body of a dead Union soldier. While looking for a pocket watch, he found cigars, a memorandum book, and some papers.

“Well, William, you must give me the papers, and you may keep the cigar-case.”

Littlepage passed the papers to Halbach, commenting that the man he had taken them from had a wooden leg.

The previously captured Confederate lieutenant had been listening. At this statement he jumped into the conversation.

“There, you have killed Col. Dahlgren, who was in command of the enemy. His men were devoted to him, and I would advise you all to take care of yourselves now, for if the Yankees catch you with anything belonging to him, they will certainly hang us all to the nearest tree.”

In the morning, Halbach took one look at the papers and gave them to Lieutenant Pollard. Pollard took them to Colonel Beale of the 9th Virginia Cavalry. Beale ordered Pollard to deliver them personally to either Wade Hampton or Fitzhugh Lee.

Meanwhile Cooke decided the only way to escape was by breaking up into small groups and sneaking through the Confederate lines in the dark. “The men were dismounted and ordered to drive their sabres into the ground and picket their horses to them, it being impossible to kill the animals without attracting notice. The Spencer carbines were destroyed by removing and throwing away, or burying the chambers, and breaking the magazine tubes. The men were instructed to take only their belts, revolvers and haversacks, that they might not be impeded by a heavy load which would be soon abandoned, affording evidence of the trail, and assist pursuit.” About 40 troopers tried to escape but were eventually caught. The remainder were too exhausted to try, and were captured in the morning.

Revenge! For Dahlgren!

When Kilpatrick heard about the mistreatment of Dahlgren’s body (someone put his wooden leg on display in a store window in Richmond, and another cut a finger off to remove a ring), he decided to get revenge by a punitive raid to King and Queen Courthouse.

He planned to engage the Confederates in front, driving them slowly down the road while 2,700 infantry landed at Shepherd’s Landing to cut off their retreat. By the time infantry arrived however, the cavalry had already driven the Confederates past.

Late on the 10th, the Union cavalry destroyed Confederate supplies in town while Beale, impotent with his smaller force, watched from a distance. On the 11th, the Union cavalry withdrew toward the peninsula.

The Confederates buried Dahlgren’s body where they killed him. They later dug it up to bury it in an unmarked grave in Oakwood Cemetery. Union spies removed the body and hid it elsewhere to keep angry Virginians from desecrating it.

Rear Admiral Dahlgren wanted his son’s body returned. This put Union Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler in the awkward position of demanding its return while knowing the Confederates could not produce it. He could say nothing without revealing the existence of Union spies in Richmond.

: “… Destroy and Burn the Hateful City”

Thus, in nearly all respects, Kilpatrick’s raid on Richmond was a dismal failure. But there was more.

The papers found by Littlepage had passed up the Confederate chain of command. When published in Richmond newspapers, they caused outrage. Seddon made photographic copies of two papers and sent them to Lee.

On April 1, Lee wrote Meade about the papers found on Dahlgren’s body. To show the authenticity of the papers, he enclosed the photographic copies. In his cover letter, he cited the questionable phrases. In a signed copy of an address to his men, Dahlgren wrote: “… destroy and burn the hateful city; and do not allow the rebel leader Davis and his traitorous crew to escape.” On the other paper (unsigned) Dahlgren had written: “… once in the city it must be destroyed and Jeff. Davis and cabinet killed.”

Meade already knew about the papers, having read them in Richmond newspapers. He ordered an investigation on March 14 to determine whether Dahlgren had made the address.

Kilpatrick replied:

“… I have carefully examined officers and men who accompanied Colonel Dahlgren on his late expedition.

“All testify that he published no address whatever to his command, nor did he give any instructions, much less of the character alleged in the rebel journals in the memorandum following his address. All this is false and published only as an excuse for the barbarous treatment of the remains of a brave soldier.”

No Rest in Richmond

On April 17, Meade answered Lee’s letter. “In reply I have to state that neither the United States Government, myself, nor General Kilpatrick authorized, sanctioned, or approved the burning of the city of Richmond and the killing of Mr. Davis and cabinet, nor any other act not required by military necessity and in accordance with the usages of war.”

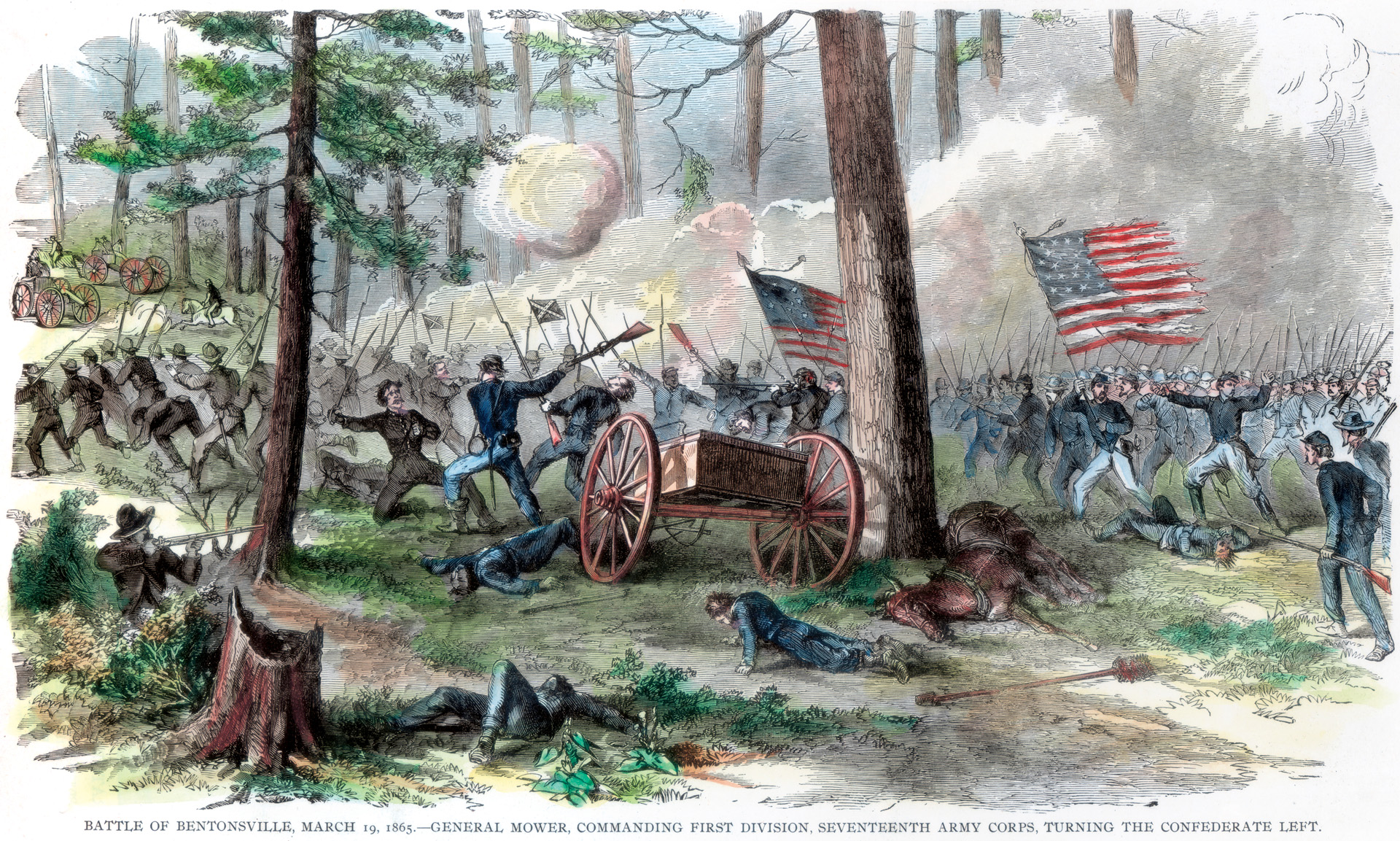

By then Kilpatrick had been transferred west. New leaders were in charge of the Union army, and within weeks Richmond was again under attack by cavalry raiders. Even worse—for the Richmond citizens—behind them lay even more muscle: The Army of the Potomac was about to step off south, somewhat in the footsteps of the hapless bluecoat raiders. Only they would not be led by Ulric Dahlgren and Judson Kilpatrick, but by George Meade and U.S. Grant.

You may consider putting captions under the pictures so reader knows. Very good, detail in the article. .