By David Alan Johnson

King Edward IV could not have asked for better news. On the evening of May 3, 1471, his scouts reported that the army of his Lancastrian archrival, Queen Margaret of Anjou, was camped a few miles south of the abbey town of Tewkesbury with its back to the River Severn.

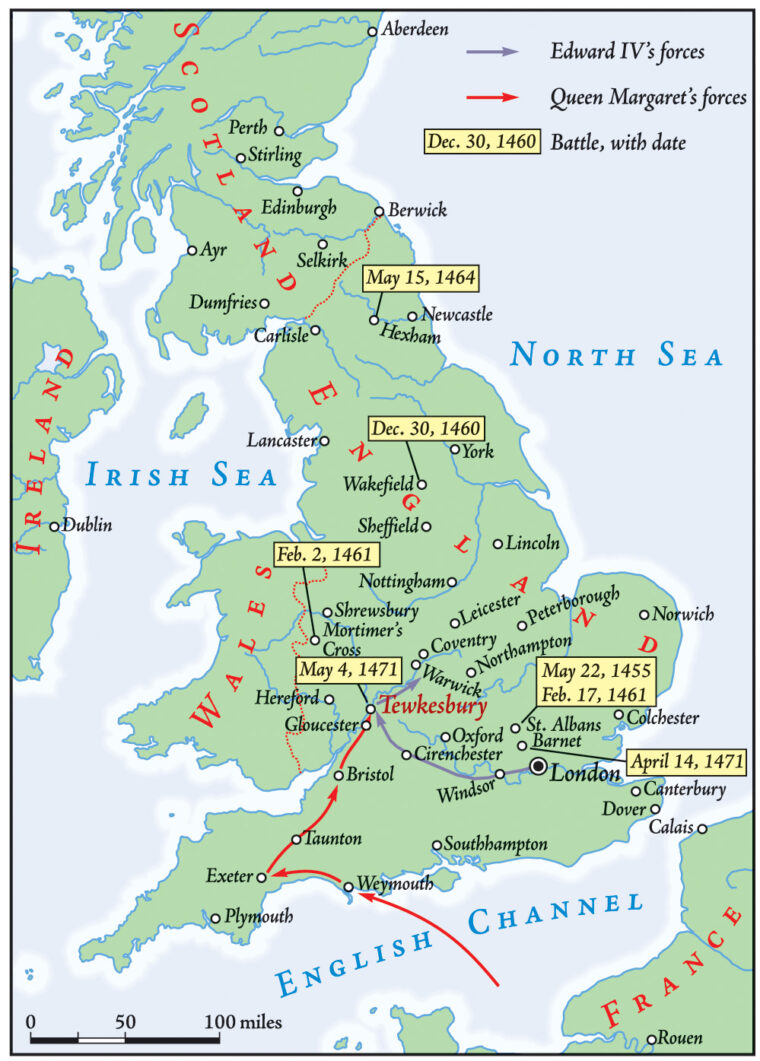

Edward, the former Earl of March and son of the Duke of York, had been hunting Queen Margaret’s force for over a week. The queen had returned to England on April 14, landing at Weymouth in Dorset after eight years of exile in France. She was met by supporters of her husband, the feeble-minded Henry VI, including Edward Beaufort, Duke of Somerset.

Somerset advised Margaret to fight Edward, who was keeping her husband prisoner in the Tower of London. But Somerset realized that he did not have enough men to march on London and face the king. First, Somerset advised, it would be necessary to travel to Wales and join forces with Jasper Tudor, the Earl of Pembroke, an enemy of Edward and an almost legendary figure in Welsh history. (He was also the uncle of Henry Tudor, who would become Henry VII.) During this “royal progress,” Margaret and Somerset would also be able to pick up as much support as possible for their army, which would be indispensable in the coming battle with Edward. The queen began moving northward toward the Welsh border, gathering recruits along the way.

Margaret Joines Forces with Jasper Tudor

On April 23, Edward learned that Margaret had arrived in England and that she was on her way to Wales to join forces with Jasper Tudor. He began his pursuit on the following day, driving his army northwest from Windsor to the Welsh border. Six days later, Edward and his troops were in the vicinity of Cirencester, in Gloucestershire, about 60 miles from Margaret. The speed of this advance took Margaret and Somerset by surprise. They began driving their own men up the Severn River valley toward Gloucester, the nearest bridge across the Severn. It was vitally important that they cross the Severn before Edward overtook them.

Edward’s scouts did their best to stay in contact with the Lancastrian force. At three o’clock in the morning on May 3, a patrol reported that Margaret and Somerset were moving toward Gloucester. After discussing the situation and the Lancastrian army’s position with his senior commanders, Edward sent word to the commander of the Gloucester garrison, Sir Richard Beauchamp: “Hold up the Queen’s progress for as long as possible.” Sir Richard did as he was told. When Margaret and Somerset reached Gloucester they found the city gates locked and the garrison in arms against them.

Somerset was furious over this totally unexpected setback and announced he intended to take the city by force. His commanders managed to talk him out of the idea—they pointed out that Edward was only a few miles distant and closing fast. The best course open to them was to push their troops northward toward the next crossing—Tewkesbury, about 10 miles farther on. Somerset reluctantly agreed. When the situation was explained to her, Margaret also agreed with the advice of her officers.

The Vanguard Arrives

The vanguard of the Lancastrian forces arrived south of Tewkesbury just after 4 pm on May 3, several hours after being turned away at Gloucester. Because the army was near exhaustion from the forced march over rough terrain, a situation made even worse by that spring’s abnormally hot weather, Somerset reasoned that the time had come for him to turn and face Edward. If he started ferrying his men across the Severn at Tewkesbury, he faced the probability that Edward would attack while half of his force was on the far side of the river and the other half was still waiting to cross. And his men could not endure another forced march to the next crossing. There was really no choice but to turn and fight. Queen Margaret agreed.

On the evening of May 3, Edward made camp at Tredington, about three miles from the Lancastrians. His officers saw to it that their men had a good meal, “such meat and drink as he had caused to be carried with him,” and the troops settled down to rest as best they could. They knew that shortly after daybreak they would attack the men who were just over the horizon.

Within the past month, Edward had already won an impressive victory over the Lancastrians. On April 14—the same day that Queen Margaret landed at Weymouth—his army routed a force led by Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick (called “the Kingmaker”) at Barnet, north of London. After three hours of particularly savage fighting, “the enemy were in full flight, casting away their weapons as they ran.” Warwick and his brother John Neville, Earl of Montague, were both killed in the fighting. Their bodies were displayed outside St. Paul’s Cathedral for two days, “so that the end of the House of Neville might be known to all.” King Henry, the ultimate pawn in this power struggle, still remained in the Tower as Edward’s prisoner.

Edward was well aware that he now had the chance to end the Lancastrian opposition to his reign once and for all. In the morning, he would confront Queen Margaret and Somerset in battle. If he won, the House of Lancaster would no longer have the power to challenge him and the civil wars that had cost so many lives, including his father’s, would finally come to an end.

By 1471, England had been fighting a series of civil wars for 16 years. These were a struggle of survival between Margaret of Anjou, the driving force behind the House of Lancaster, and the rival House of York. Because Lancaster’s heraldic badge was a red rose and York’s was a white rose, the long conflict came to be known as The Wars of the Roses.

It was Queen Margaret’s ruthlessness and her manipulation of the weak and feeble-minded King Henry VI that precipitated the wars in the 1450s. She and her Lancastrian favorites excluded any lords who might threaten their control over King Henry, and whoever controlled the king controlled the government.

Richard, Duke of York

Margaret’s main rival for power was Richard, Duke of York. The queen had good reason to fear York: He had a better claim to the throne than her husband did. He was also much more popular than either Margaret or her despised Lancastrian followers. She tried to rid herself of the duke by banishing him to Ireland for several years, but by 1450 he had returned to England and was able to enlist a following of several thousand retainers as his personal army. Hostility between the duke and Margaret continued to escalate, and in May 1455 York and his forces met the queen’s army at the first Battle of St. Albans. York scattered the Lancastrians and briefly took possession of King Henry, but the battle was not conclusive. During the next several years, other battles between Lancaster and York were fought; Mortimer’s Cross (February 2, 1461), second St. Albans (February 17, 1461), and Hexham (May 15, 1464).

The Duke of York was killed at the Battle of Wakefield on December 30, 1460. Margaret, however, was not satisfied with simply killing her enemy. She had his body decapitated, then had his head carried to the city of York and impaled on a pike above Micklegate Bar “so York may overlook the town of York.” This was one event that Shakespeare got right. The duke’s son, Edward, claimed the crown and was proclaimed King Edward IV in Westminster Abbey on March 4, 1461. As for Henry VI, he had become “no more than an inert prize of savagely contending factions,” according to Paul Murray Kendall in The Yorkist Age. In 1465, he was captured and imprisoned by King Edward in the Tower of London.

Although Henry was now safely in Edward’s custody, his very existence made him a threat to Edward. Margaret of Anjou was more determined than ever to restore her husband to the throne. The savage war between Lancaster and York continued for the next decade, as Margaret persisted in her attempts to restore Henry. She was always able to raise an army of followers, which included the Earl of Warwick. Warwick had been an ally of Edward’s, but because of his enormous ego, he had a falling out with the king. Warwick never forgave Edward for marrying a commoner, Elizabeth Woodville, without first consulting him.

A Commander to be Reckoned With

Warwick may have been vain and arrogant, but he was also a commander to be reckoned with. In September 1470, while Queen Margaret was in France, Warwick and his army forced Edward to leave England for the Low Countries and Henry was reinstated as king. It looked as though the House of Lancaster had completely routed Edward and the Yorkists without fighting a battle.

Edward, however, was not one to accept defeat gracefully. He returned to England in March 1471, looking to settle old grievances. He had already disposed of the Earl of Warwick at Barnet. In the morning, he would meet Queen Margaret and Somerset in battle.

Besides being king, Edward was also a soldier and a commanding general. He certainly looked the part. Contemporary writers almost always used superlatives to describe Edward. He was “the tallest,” “the fairest,” “the strongest.” When his coffin was opened in 1789, his skeleton measured 6 feet 3 inches—tall for the 21st century, but gigantic for 15th-century England. He also knew how to use his height to advantage. In battle, he was always in the van and could be seen by all of his soldiers, usually hacking away at the nearest enemy with a battle-axe or a mace. Edward always led by example. Inspired by the king, his men always tried to give more than their best.

Besides possessing physical strength and courage, Edward also had the ability to outthink as well as outfight his enemies. At Tewkesbury, he placed 200 men-at-arms in Tewkesbury Park to protect his left flank. This was fairly typical of Edward—trying to anticipate a surprise flanking movement and, in so doing, taking the enemy completely by surprise.

Boldness, Brains and Luck

Knowing the finer points of tactics, flanking movements and feints gave Edward an edge on the field. He also realized that the enemy first had to be brought to battle before he could outflank and outmaneuver them. The offensive was another characteristic of Edward’s generalship. At both Barnet and Tewkesbury, Edward placed his forces in a position where battle could not be declined by the Lancastrian commander. By challenging the enemy, Edward was able to force a battle on terms that gave him the advantage.

In addition to having boldness and brains, Edward possessed another trait that would prove just as valuable—luck. In several instances, the Yorkists won decisive battles because of happy coincidences. At Towton, on March 28, 1461, the weather worked in favor of Edward’s troops. The wind blew snow in the face of the Lancastrians, blinding the enemy’s archers and allowing Yorkist foot soldiers to close with and eventually turn the Lancastrian left flank. At Barnet, heavy fog covered the field. Neither side could see more than a few feet, a condition that could have brought disaster to either Lancaster or York. But, once again, luck favored Edward. Two Lancastrian units collided and, mistaking each other for the enemy, attacked their fellow soldiers. In the confusion, Edward launched a successful attack of his own. The Yorkists won decisively, which paved the way for the confrontation at Tewkesbury.

Edward’s skill, resourcefulness, and luck combined to make him one of the most successful commanders of his day. The historian Paul Murray Kendall, author of several books on the 15th century, summed up Edward’s military career: “King Edward was the mightiest warrior in Europe.”

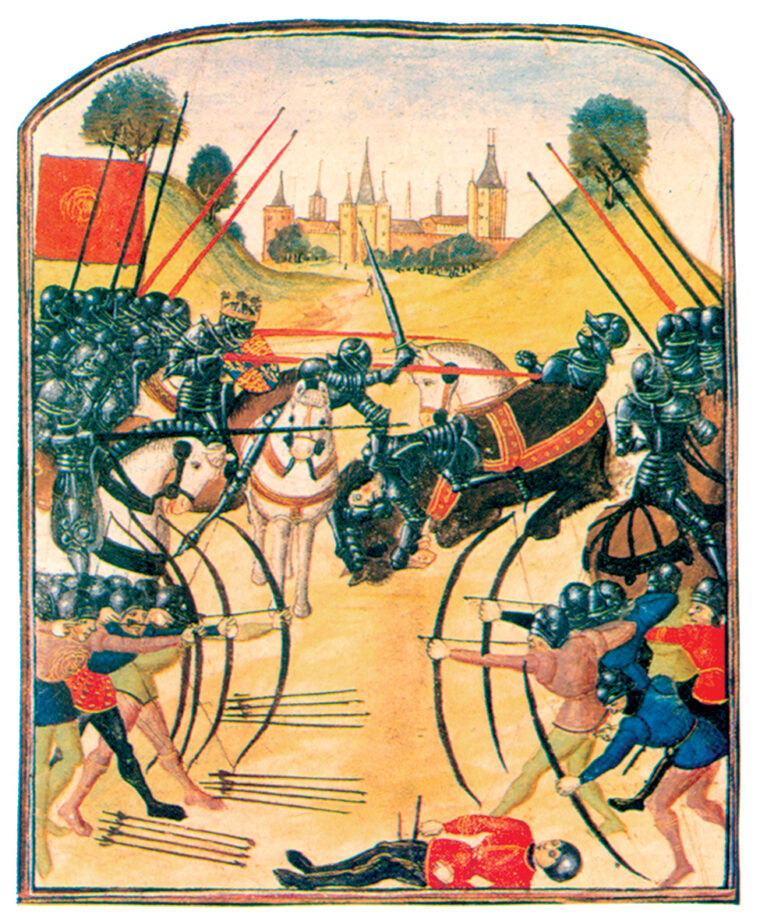

The soldiers who faced each other in the meadow south of Tewkesbury enjoyed the reputation of being the finest in northern Europe. It was a reputation earned by brilliant victories against the French in the Hundred Years War, specifically the battles of Crécy (1346), Poitiers (1356), and Agincourt (1415). English tactics had not changed very much since the days of Crécy and Agincourt. Troops still fought on foot and were formed into divisions or “battles.” These battles consisted of men-at-arms carrying swords, battle-axes, or spears. On the left and right flanks of the battles stood groups of archers armed with their formidable long bows. Also on the field at Tewkesbury were cannon. King Edward had a keen interest in artillery, which was the new technology of the 15th century, and personally supervised the readiness of his ordinance.

Knights in Shining Armor

On the morning of May 4, Edward led his army onto the field south of Tewkesbury. According to a contemporary chronicler, “The King appareled himself; and all his host set in good array; displayed his banners; did blow up the trumpets … and advanced directly on enemies.” The Yorkist army was deployed in three battles: Edward commanded the center; his brother, the 19-year-old Richard, Duke of Gloucester (the future Richard III), commanded the left wing; and William, Lord Hastings, led the right. It must have been quite an impressive sight—lords in their shining armor, archers on the flanks wearing the livery of their town or their lord, and cannon, which were probably mounted in the gaps between the divisions. Flags and banners waved above the troops, town flags and personal coats-of-arms of the many lords and officers, with the red and white Cross of St. George banner in the center.

On the other side, several hundred yards to the north, the Lancastrian forces offered a similar spectacle. Although Queen Margaret was present at Tewkesbury—trying to rally her troops and promising them booty and honors—command fell to the Duke of Somerset.

For Somerset, the impending battle had a special importance. His father and his elder brother, the third and fourth Dukes of Somerset, had been killed in battle against the Yorkists (at the first battle of St. Albans in 1455 and at Hexham in 1464, respectively). Tewkesbury would be his chance for revenge against Edward and the House of York.

The Lancastrian forces were also formed into three battles. Somerset commanded the right wing; the left was led by the Earl of Devonshire; and the center had Edward, Prince of Wales, as its nominal commander, although the real leader was John, Lord Wenlock. There were those in the Lancastrian army, however, who did not trust Wenlock because he had changed parties twice since the wars had begun. Starting as a Lancastrian, he had changed to the Yorkist side before reverting to a Lancastrian again.

Cannons vs. Sheer Numbers

Edward’s Yorkists numbered between 5,000 and 6,000 men—about 3,000 infantry and between 2,000 and 3,000 cavalry. The Lancastrian force consisted of about 7,000 men. The Lancastrians were greater in number, but the Yorkists had more cannon. Even more important, Edward’s army also had a psychological edge—his soldiers had met and routed the Earl of Warwick’s force at Barnet less than three weeks before and were full of confidence.

Edward, however, was not entirely at ease. To the left of the Yorkist army was a wooded area known as Tewkesbury Park. Close by the left battle in the formation and dense enough to conceal a fairly sizable force, this heavily wooded area would be the perfect place for a Lancastrian ambush party to wait for a chance attack his left flank. To counter any threat that might be lurking, Edward sent 200 horsemen (some accounts say spearmen) into the woods to look for enemy soldiers. If none were found, the horsemen were instructed to employ themselves wherever an opportunity presented itself. This would turn out to be an extremely lucky and farsighted move.

The battle commenced when the Lancastrian artillery opened fire while the two armies were still some distance apart. Edward’s gunners returned fire and his archers loosed a volley of arrows toward the enemy. In most battles of the Wars of the Roses, the opening salvo would have been followed by a charge on both sides. At Tewkesbury, however, a series of trenches and drainage ditches crisscrossed the field between the two armies, making it difficult for the opponents to close with each other. As a contemporary writer put it, “In the front of their field were so evil lanes and deep dikes, so many hedges, trees and bushes that it was right hard to approach them near, and come to hands.”

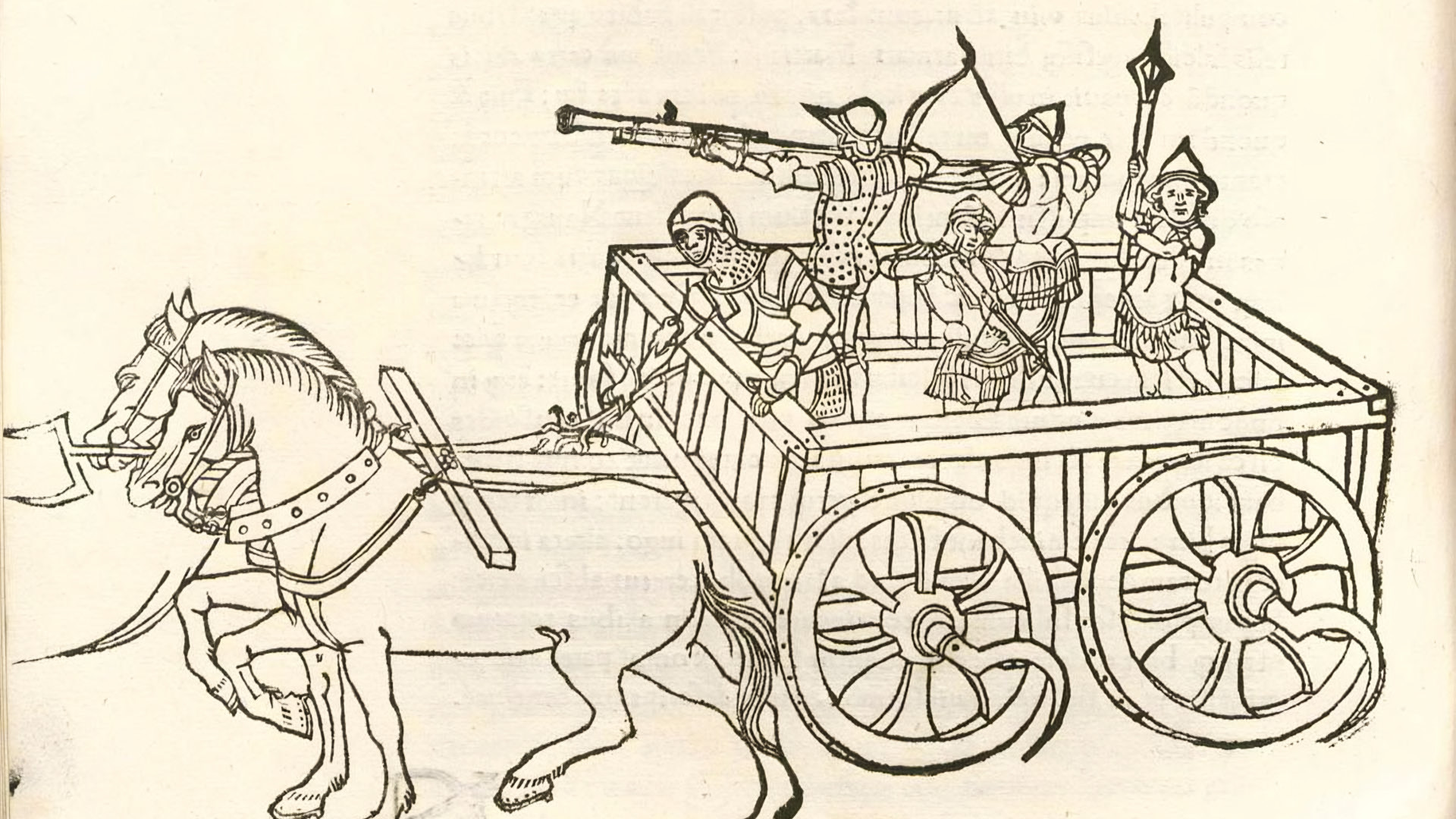

While the men groped their way over the drainage ditches and trenches, the cannon and bowmen continued to fire. Edward’s force included a small group of German arquebusiers (the arquebus was a heavy matchlock weapon, an early form of musket that was so awkward it had to be fired from a support). The cannon and small-arms fire did their share of damage, both real and psychological; the sight of a stone cannon ball bouncing in one’s direction must have been a terrifying spectacle. Just as during the Hundred Years War, the archer and his long bow dominated. The bow itself was about 6 feet long and was usually made of elm or yew wood. Archers kept their supply of iron-tipped arrows in a leather keeper that hung from their belts, allowing them to fire about 12 arrows per minute. A keeper held about two dozen arrows, giving the archer easy access to his arrows. This was a much faster rate of fire than that of any musket or cannon, and the iron point was capable of piercing armor at a range of 250 yards. The results brought havoc to the ranks of the enemy.

An Unprotected Flank Creates An Opportunity

Arrows and cannon volleys slowed the advancing forces still further, but they continued to close with each other. During that long, slow march, the Duke of Somerset noticed that Edward’s left flank appeared to be unprotected. From his position, it appeared that the Duke of Gloucester’s division was open, with no troops covering the gap between Gloucester’s left and the woods of Tewkesbury Park. It seemed like a golden opportunity—an attack on the left flank would put Gloucester’s division in peril. If the left division broke and ran, the entire Yorkist army would be in a difficult, if not altogether untenable, position. It was a gamble, but Somerset decided that the stakes were worth the risk.

While hand-to-hand fighting was developing all along the front, Somerset led his attack into the area between the woods of Tewkesbury Park and Gloucester’s left. His men crashed into the left side of Gloucester’s division with flailing swords and battle-axes, taking the enemy completely by surprise. The Yorkists quickly recovered from the shock, however, and began fighting back.

At that critical moment, Edward showed one of the characteristics that made him an outstanding commander: the ability to size up the situation at once, even in the middle of a battle, and quickly take countermeasures. He personally led an attack against Somerset with troops of his own household and succeeded in pushing the enemy troops across a dike and a hedge and back toward the little wood.

At about the same time, the 200 men that Edward had sent into Tewkesbury Park saw their chance. They burst out of the woods and began battering Somerset’s men from the rear. This time, it was Somerset’s turn to be taken by surprise. His force quickly began to disintegrate, then his men broke and ran.

Somerset himself was wounded in this counterattack. He mounted a horse and rode back to confront the Duke of Wenlock, who commanded the Lancastrian center. Wenlock had taken no action at all so far, even though he could see that Somerset needed support. Somerset angrily accused Wenlock of changing sides once again. After cursing him as a traitor, he cracked Wenlock’s skull with a battle-axe, killing him instantly.

“Bloody Meadow”

The sight of the commanding general killing one of his own senior commanders did not help to bolster Lancastrian morale. Somerset tried to rally his troops, but the men were shaken both by the failure of Somerset’s attack and by his killing of Wenlock. When Somerset’s flank attack failed, Edward and the Duke of Gloucester were able to push the Lancastrians back toward the town of Tewkesbury and the River Avon, which flows southward into the Severn just to the west of the town. Edward’s troops could smell blood and pursued the fleeing Lancastrians with relish. Their furious attack turned the already disorderly retreat into a rout. The luckier men escaped into the town and sought sanctuary in Tewkesbury Abbey. Some were slaughtered while trying to cross the Avon on a field still known as “Bloody Meadow.” Others made it to the river, but drowned while trying to swim across. Edward’s objective, however, was not to kill the common soldiers. The maxim of the Wars of the Roses was, “Spare the commons, kill the lords.” The Yorkists certainly carried out this credo at Tewkesbury.

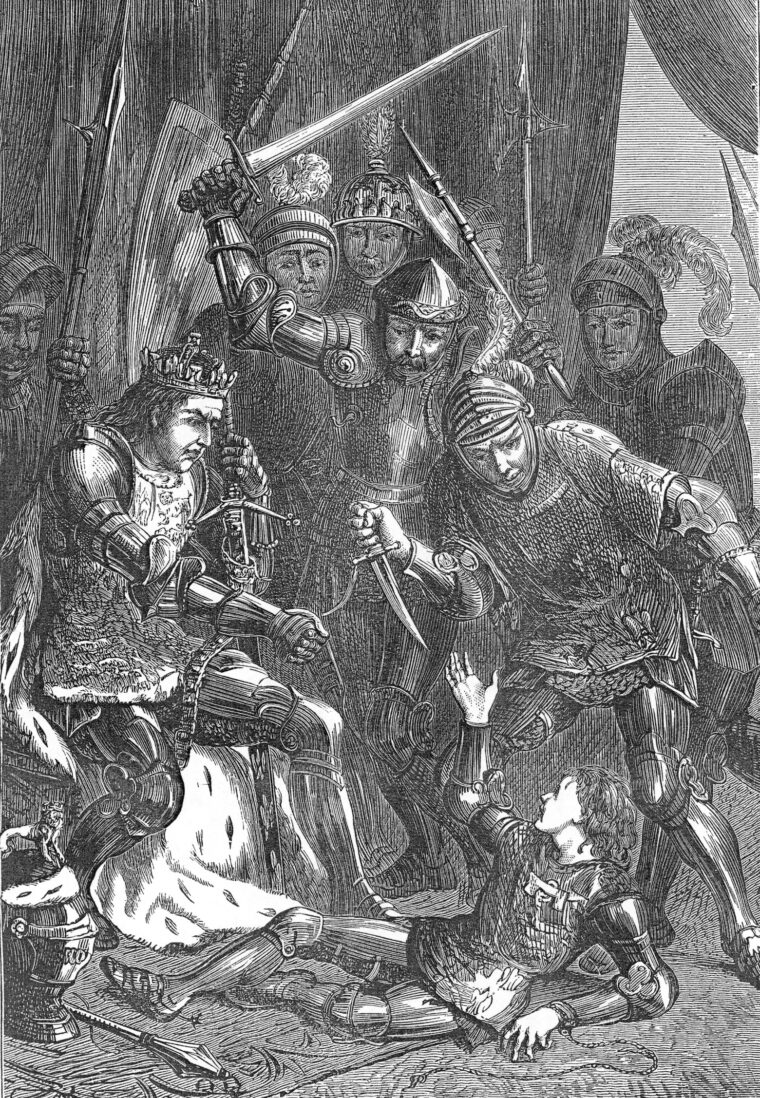

Among the lords who were killed was Edward, the 17-year-old Prince of Wales, son of Margaret of Anjou and Henry VI. The young Edward was cut down after having been captured, even though he begged for mercy. (There is no evidence that he was murdered by Richard of Gloucester, in spite of Shakespeare.) Yorkist soldiers entered local churches and dragged members of the Lancastrian nobility outside before killing them. The Duke of Devonshire was one Lancastrian who died in this manner. When Edward learned that the Duke of Somerset and several of his field commanders were inside Tewkesbury Abbey, he personally entered the Abbey, despite the protests of the abbot. Somerset was not killed on the spot, but was seized and taken out of the Abbey to be tried for treason. According to the Tewkesbury Abbey Chronicle, the Yorkists did kill several Lancastrians after they had been granted sanctuary. This was considered an act of desecration and no mass was performed inside the Abbey until it was reconsecrated by the Bishop of Worcester the following month.

All prisoners were tried by a hastily convened court on May 6. (The day immediately following the battle was a Sunday, and thus no proceedings were held.) The Duke of Gloucester, as Constable of England, presided over the hearings and handing down predictably harsh sentences. The Duke of Somerset, along with other Lancastrian officers, was beheaded in Tewkesbury’s marketplace immediately following the trial.

Edward’s Victory

The Battle of Tewkesbury lasted about three hours. A contemporary writer claimed that 3,000 Lancastrians died in the fighting. This was an exaggeration, since that would have constituted 50 percent of Margaret’s army. Losses were probably closer to 1,000 dead. According to Sir John Paston, who fought with the Lancastrian side at the Battle of Barnet, 1,000 Lancastrians were killed in the course of that battle. The fighting at Tewkesbury was just as fierce, so the losses were probably comparable.

Edward’s victory at Tewkesbury secured peace for the rest of his reign, the battle and its aftermath virtually wiping out the House of Lancaster. After the battle, Margaret of Anjou fled the scene of battle in a carriage, but was captured as she took refuge in a nearby church. She was allowed to return to exile in France and caused no more mischief for Edward. Henry VI, still a prisoner in the Tower of London, was said to have died of “pure displeasure and melancholy” when he learned of the death of his son, the Prince of Wales. But when Henry’s tomb was opened in 1910, his skull was found to have been “much damaged” and a part of it was stained with something that might have been blood. In all likelihood, he was put to death by order of King Edward. The demise of both Henry and the Prince of Wales effectively put an end to any serious challenges to Edward’s authority as king.

Although Edward left for Coventry following the battle, “to deal with new risings there,” he no longer had any real rivals for the crown. The Battle of Tewkesbury made Edward IV undisputed king.

An excellent description of the events leading up to the Battle of Tewkesbury. I walked the battlefield last year with an excellent guide, and have had an urge to return ever since. Sitting at Tewkesbury Park again made this article particularly good for me. Thank you.