By Eric Niderost

On August 2, 1914, Russian Czar Nicholas II appeared on the balcony of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg to formally proclaim a state of war between Holy Russia and its bellicose neighbor, Germany. Thousands of people packed the square in front of the palace, sweltering under a brutal summer sun but still exultant. To them Nicholas was the “Little Father” who would lead them to victory over their hated foe.

Nicholas, bearded and dressed in a simple khaki uniform, was accompanied by his elegant wife, Alexandra. The czar tried to speak, but the crowd was so vast that the noise and tumult of the assembled throngs drowned out his words. Suddenly, the crowd knelt and spontaneously began singing “God Save the Czar,” the national anthem. In the emotional moment many people began to weep, including the czar and the czarina. There was no doubt in anyone’s mind that Russia would prevail against Germany.

But wars are not won with speeches and tears, and before long reality set in. Russia possessed the largest army in Europe, with a peacetime strength of 1,400,000 men. When fully mobilized, another 3,100,000 reserves could be added to that total. Once aroused, the Russian bear could be a formidable opponent. The Germans rightly feared an army that was nicknamed “the Russian steamroller” and was seemingly capable of flattening its enemies with sheer numbers.

The Ambitious War Plans of Tsar Nicholas

Germany seemed vulnerable on paper because Russian-controlled Poland—the so-called Polish Salient—pressed like a mailed fist against Germany’s western and northwestern borders. As war plans evolved, Russia’s Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Eighth Armies would be deployed against Germany’s ally Austria-Hungary. The Ninth Army would be kept in the St. Petersburg area to guard against enemy naval incursions. That left the First and Second Armies free for operations against the Germans.

Meanwhile, France was left virtually alone to face the German might. According to the Schlieffen Plan, Germany’s long-standing blueprint for a two-front war in Europe, seven-eighths of the German Army would swing in a wide arc across Belgium and northern France, defeating French forces in detail. Once France was defeated, the Germans could then turn east and deal with the Russians. The plan was based on the theory that full Russian mobilization would be glacially slow. On August 4, French ambassador Maurice Paleologue called on the czar to impress upon him the need for haste. He implored Nicholas to take the offensive immediately, before the French Army was crushed. Convinced, the czar assured the ambassador that the Russian Army would attack as soon as mobilization was complete.

Paleologue next called on the Russian commander in chief, Grand Duke Nicholas, the czar’s cousin, commonly called Uncle Nicholas. At six feet, six inches tall, Nicholas literally towered over his contemporaries. He was known as a competent if not particularly brilliant soldier. The French ambassador was blunt: “How soon will you order the offensive?” he asked. “As soon as I feel strong enough,” the Grand Duke replied. “It will probably be the fourteenth of August.” On paper, at least, the Russians had promised that they would begin an offensive 15 days after the start of mobilization—well before German calculations assumed they would.

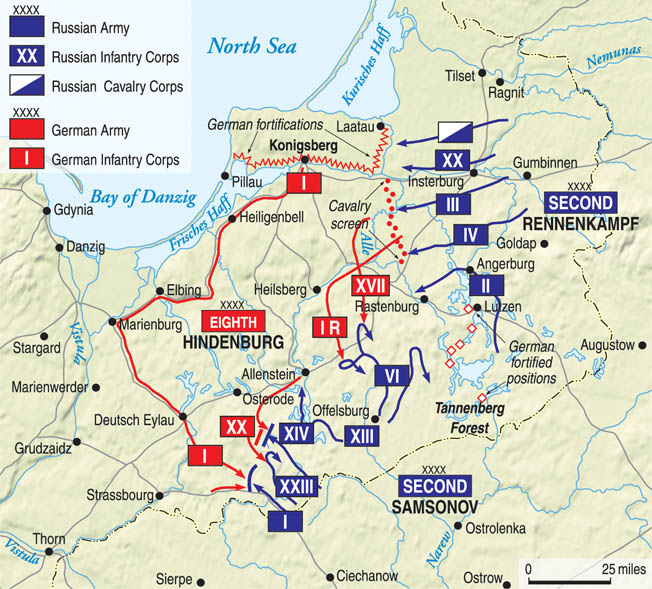

It was decided that the first Russian offensive would be directed against East Prussia. General Yakov Zhilinsky, commander of the Northwest Front Group, had the First and Second Armies to achieve their objectives. The First Army, under General Paul von Rennenkampf, consisted of six and a half infantry divisions and five cavalry divisions, some 210,000 men altogether. They were to strike west, pushing forward in the direction of Königsberg and attacking any German forces in their path. Meanwhile, the Second Army, some 206,000 effectives under General Alexander Samsonov, would come up from the south, swinging around the Masurian Lakes region into the rear of the engaged German forces.

The ambitious plan was nothing less than a double envelopment that would rival Hannibal’s triumph centuries before. With the bulk of the German forces tied up in the west, the capture of East Prussia would be an unforeseen calamity. Berlin itself would be threatened, and if the German capital was captured, the Germans would have to sue for peace. The Russian plan was bold and depended much on precise timing, but with enough luck there was a chance they could pull it off.

Russia’s Weaknesses

Yet in many ways Russia remained unprepared for modern war. The disastrous Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 had been a wake-up call, a stern warning to modernize the Russian armed forces. Some reforms were put in place, but it was estimated that Russia would not be ready for a major European conflict until 1917. Above all, modern war demanded that nations have modern transportation systems and a fully functioning industrial base to sustain armies in the field. For every factory in Russia, there were 150 in Great Britain.

Anticipating war with Germany, France poured vast sums of money into Russian railroad construction, but in 1914 the results still fell short of what was needed. For every yard of Russian track per square mile, Germany had 10. As if that weren’t bad enough, Russian railroads had a different gauge than German railroads. That meant that Russian supply trains had to halt at the border and transfer their cargo to horse-drawn transport. The hasty mobilization meant that many Russian units lacked field bakeries and even medical supplies. There was also a crippling shortage of telephone wire, telegraph equipment, and trained signal corpsmen. There were few trained cryptographers, which meant Russian messages were often read by the Germans.

The Germans were aware of these weaknesses, and they were shocked and surprised when the Russians assumed the offensive so quickly. The task of guarding East Prussia was assigned to Lt. Gen. Maximilian von Prittwitz’s Eighth Army. Prittwitz was 66 years old and so overweight that he was called “Fatty” behind his back. Lethargic and overcautious, the only thing Prittwitz had going for himself was that he had a highly competent deputy chief of staff, Colonel Max Hoffmann. Hoffmann analyzed the situation and concluded that Rennenkampf’s First Army would invade first. If and when the Russians crossed the frontier, Hoffmann wanted to meet them at Gumbinnen, 25 miles from the border. Hoffmann wanted to lure the Russians into East Prussia, forcing them to stretch their supply and communications lines before pouncing on them by surprise.

“Kosaken Kommen!”

In the meantime, advance elements of the First Army approached the frontier. General Basil Gourko led a cavalry division and an infantry division across the border as dawn was breaking on the morning of August 12. There was some skirmishing, but German troops quickly melted into the countryside. Gourko’s objective was the town of Marggrabowa, some five miles from the Russian border. Marggrabowa’s streets were empty, but in the distance Gourko heard the chatter of a German machine gun. The Russians opened up with their own machine guns, and the German gun fell silent. Gourko and a squadron of dismounted lancers quickly took the center of town. There was no further resistance. Fearful townsfolk peered from upper-story windows but eventually came out to watch the invaders.

Although there were still people in town, most were elderly. It seemed that most of the townsfolk, along with the German soldiers, had fled the area. It was a pattern that would be repeated in the coming days. Hundreds, then thousands, of common Germans were on the roads, fleeing westward with the dreaded cry of “Kosaken kommen!” on their lips. The Cossacks, those hard-riding horsemen of the steppes, were particularly—and rightly—feared by both soldiers and civilians.

This was bad enough from the Germans’ point of view, but worse was soon to follow. General Hermann von François, commander of the Eighth Army’s I Corps, didn’t like the Prittwitz plan of engaging the Russians so deep inside German territory. Most of his men were native East Prussians, and the idea of yielding ground to the enemy rankled François. He felt that he knew better than the dunderheads at headquarters.

Rennenkampf’s First Army crossed into East Prussia in the early morning hours of August 17. As Rennenkampf’s III Corps approached Stalluponen, they detected elements of François’s I Corps. Soon battle was joined, with François watching the action from a church steeple. German commanders back at headquarters were shocked, then enraged, to receive a message from François that he was fighting the Russians at Stalluponen, only five miles from the Russian border. François had disobeyed orders, and in the German Army such insubordination was a cardinal sin. François was immediately ordered to break off the action and retire to Gumbinnen, 20 miles away.

Rennenkampf’s First Army crossed into East Prussia in the early morning hours of August 17. As Rennenkampf’s III Corps approached Stalluponen, they detected elements of François’s I Corps. Soon battle was joined, with François watching the action from a church steeple. German commanders back at headquarters were shocked, then enraged, to receive a message from François that he was fighting the Russians at Stalluponen, only five miles from the Russian border. François had disobeyed orders, and in the German Army such insubordination was a cardinal sin. François was immediately ordered to break off the action and retire to Gumbinnen, 20 miles away.

François ignored the messages, so a major general was sent to deliver the order in person. “The General-in-Chief orders you to stop the battle immediately!” the major general shouted. François was not cowed. “Inform General von Prittwitz that General von François will break off the engagement when he has defeated the Russians!”

As events unfolded, the Russian 27th Division was mauled and some 3,000 Russian prisoners were taken. The “Slavic horde” was checked, at least for the moment, and François belatedly fell back as he was originally ordered. Although one division had been badly chewed up and retired for reorganization, the rest of Rennenkampf’s army was intact. The advance would continue.

The Battle of Gumbinnen

François’s I Corps opened the Battle of Gumbinnen with an artillery barrage in the predawn hours of August 20. At 4 am, the German infantry groped its way forward in the predawn darkness, stumbling toward the Russian lines on the far right. The sun soon rose over an awesome spectacle—line after line of Germans in field-gray uniforms, distinctive in their pickelhaube spiked helmets.

Russian artillery opened up with a deafening roar, carpeting the area with well-placed salvos. The neat gray lines were torn asunder, bloodied soldiers tossed about like rag dolls. For once, the Russian gunners ignored warnings about the scarcity of shells, using 440 per day when the accepted rate was 244 rounds. The Germans kept going, even though a nearby road, once stark white, was now gray with the corpses of the fallen. Then the Russian guns fell silent—they had run out of ammunition. Free of the tormenting artillery, the German I Corps pressed forward and smashed into the Russian 28th Division, decimating it in the process.

In the Russian center and left, Rennenkampf’s fortunes improved. The problem with the German attack was that it was in some respects premature. François again had jumped the gun and launched an attack before his support—General August von Mackensen’s XVII Corps and General Otto von Below’s I Reserve Corps—could come up. Mackensen and Below had a long march to the battlefield, and entered the fray only at 8 am. François’s attack on the left had alerted the Russian center and right, and the delays that Mackensen and Below experienced gave Rennenkampf time to prepare a warm reception. When Mackensen’s troops came within range, the Russian guns opened fire with horrific results. Dirty blossoms of smoke and flame ripped ranks apart, sending survivors scurrying for cover.

Some units tried to charge forward, and, out of nine advances, seven managed to reach the Russian lines, where the fighting was hand-to-hand. The Russian peasant soldier, often scorned and derided, was a tough and stubborn close-range fighter. The battered Germans were forced to give way time and again. The shelling was so heavy that some German formations never even got near the German lines. Some Russian shells landed on German ammunition wagons, heightening the confusion and terror.

At last, flesh and blood could stand no more. A company of Germans suddenly threw away their arms and ran. A neighboring company panicked and began to run as well. Soon, whole regiments, then battalions, caught the contagion of fear and took to their heels. Roads and fields were jammed with fleeing men. Staff officers tried to halt the stampede, but to no avail. Mackensen, appalled and embarrassed, rushed along in a staff car urging men to come to their senses and return to duty. The rout continued, and frightened troops did not stop until some 15 miles from the battlefield. Below’s Reserve Corps was heavily engaged by this time, but Mackensen’s sudden retreat exposed his left flank, forcing him to withdraw.

The Russians had been roughly handled in the battle’s early stages, but by nightfall it was clear that Gumbinnen was a Russian victory. All that was needed was a vigorous pursuit to clinch the triumph. Unaccountably, Rennenkampf froze. The Russian general basically did nothing to follow up his initial victory. The German forces on his center and left were in full retreat, but François’s I Corps had given the Russians a bloody nose earlier and still were somewhere on the left.

Retreat From East Prussia

Rennenkampf didn’t want to chase the Germans blindly, only to be hit on his flank by François’s somewhat battered but still potent force on the left. There were other reasons for First Army’s inactivity. Rennenkampf’s supply line was tenuous at best, and a rapid push forward might stretch it to the breaking point. He decided to stay put, at least for a few days. Meanwhile, the Russian Second Army crossed the German-Russian border on August 21-22. Samsonov had been recalled to active duty from sick leave, and he was completely unfamiliar with his new subordinates. Since there were no suitable east-west railroads in the region, the Second Army had to march to the border, foot-slogging through sandy wastes sprinkled with forests, lakes, and marshes.

The Second Army’s supply problems were even worse than those of the First Army. They marched through a virtual wilderness inhabited by a few poor and wretched Polish peasants. Russian supply trains depended on horse-drawn vehicles, and in these sandy wastes everything moved at a snail’s pace. There were few towns worth mentioning, so the Russians could not requisition food and fodder from the usual sources. By the time the Second Army crossed the German border they had been on the march for nine days. They were approaching exhaustion, and tea and bread—the staples of the Russian soldiers’ diet—were scarce. Mobilization had been so hasty that the troops even lacked field bakeries. Only a trickle of rations reached the long-suffering troops.

The German defeat at Gumbinnen sent shock waves spreading through East Prussia and Germany proper. Even before the battle, aristocratic refugees had loudly complained about their estates being overrun by Slavic barbarians. Nowhere was the consternation greater than at Eighth Army headquarters. Prittwitz was shaken to the core by stories of German soldiers turning tail and running. When the general heard reports that Samsonov’s army had crossed the border, he completely lost his nerve.

Earlier, German Army Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke had told Prittwitz to keep his army intact and, if pressed, retire to the Vistula River. But Prittwitz now decided to retreat behind the Vistula, some 200 miles away. That would leave East Prussia effectively in Russian hands. East Prussia had been the heart of the old Prussian monarchy, the historic base where Teutonic Knights had overrun and colonized the Slavic peoples. To abandon East Prussia would be unthinkable. Moreover, as the Russians pressed westward, Berlin itself would be threatened.

“I am Ready”

When Moltke heard that Prittwitz wanted to retreat immediately, he was aghast. There was no doubt about it—Prittwitz would have to be replaced. Moltke’s choice fell on Paul von Hindenburg, a retired 67-year-old general whose Prussian roots ran deep. It was said that as a lad he had actually known an old man who had been Frederick the Great’s gardener. The old soldier accepted the post with a simple, “I am ready.” General Erich von Ludendorff was chosen as Hindenburg’s chief of staff and transferred from the Western Front, where he had recently distinguished himself at Liege.

Even before Hindenburg’s and Ludendorff’s arrival, Hoffmann had persuaded his superiors, including the now-dismissed Pittwitz, to accept a daring plan he had worked out for victory. In essence, Hoffmann proposed that the Eighth Army disengage from the Russian First Army and turn south to face Samsonov’s Second Army. Only a thin cavalry screen would monitor Rennenkampf’s movements. Hoffmann wanted to turn the tables on the Russians. If all went well, they, not the Germans, would be the victims of a double envelopment. Both the German I Corps and the III Reserve Corps would be shipped by train to the right flank of the XX Corps, now facing the advancing Second Army. The I Reserve Corps and XVII Corps would also march south and take positions on the XX Corps’ left.

Hoffman was gambling that Rennenkampf would not move in support of Samsonov. If Rennenkampf stayed where he was, or continued northwestward to Königsberg, the Second Army’s fate would be sealed. But if he swung southward, he could fall on the rear of the Eighth Army as it faced Samsonov. It would be a disaster.

Hindenburg and Ludendorff approved Hoffmann’s plan when they arrived on August 23. There would still be some anxious moments because it would take several days for the German Army to redeploy. But if all went well, Samsonov’s Second Army would fall into the trap.

“Hurry Up the Advance of the Second Army”

Unaware of German plans, Samsonov was still pressing forward, urged to hurry by Northwest Front commander General Zhilinsky. “Hurry up the advance of the Second Army,” Zhilinsky demanded, “and hasten your operations.” Samsonov protested, but his pleas fell on deaf ears. The Second Army commander explained he was “advancing according to timetable, without halting, covering marches of more than 12 miles over sand. I cannot go more quickly.”

Samsonov’s supply line had broken down, literally and figuratively. Horse-drawn wagons and gun carriages became mired in the sand. Bakery wagons were missing, and foraging in enemy territory was difficult, especially in a sand-choked, marshy wilderness. Samsonov despairingly told Zhilinsky that “the country is devastated, the horses have long been without oats, and there is no bread.”

Zhilinsky would have none of it. He was certain that the Russians were on the verge of a great victory. On August 21 Samsonov’s XV Corps under General Nicholas Martos ran into elements of the German XX Corps, and fighting began. The Germans withdrew, so Martos pushed forward and took Soldau and Neidenburg, 10 miles inside the East Prussian border. When Cossack patrols entered Neidenburg, Germans began taking pot shots at them from second-story windows. Informed of this, Martos immediately ordered an artillery bombardment of the town. Half of Neidenburg’s 470 houses were destroyed in the barrage. Martos went forward, captured the town, and spent the night in the home of its mayor.

Intercepting Two Russian Messages

The Battle of Tannenberg began in earnest on August 26. The Second Army’s five corps were spread over a front of some 60 miles. The German XX Corps, hard-pressed in part because Hoffmann’s trap was not yet ready to be sprung, slowly gave way before the Russian onslaught. The Hoffmann plan called for François’s I Corps to smash into Samsonov’s left wing, but François initially refused. His heavy artillery and some of his infantry were still detraining from their long, roundabout ride from the north. Angered at this new round of insubordination, Hindenburg and Ludendorff got into a car and drove to I Corps headquarters. Confronted in person, François reluctantly gave way.

There was still the nagging fear that Rennenkampf would suddenly awaken and fall on the German rear when they were preoccupied with trapping Samsonov. Hoffmann stopped at Montovo, where a signal operator handed him two messages that had been intercepted from the Russians. They had been sent in the clear, with no attempt to cipher or encrypt them. After a quick glance at the intercepts, Hoffmann jumped back into his car and ordered his chauffeur to drive at top speed to catch Hindenburg and Ludendorff.

After a few miles, Hoffmann could see the Hindenburg staff car just ahead. Without bothering to slow down or stop their quarry, Hoffmann simply had his chauffeur drive parallel to Hindenburg’s vehicle. Hoffmann thrust the messages into the commander’s car. Both cars came to a screeching stop while Hindenburg and Ludendorff pored over intercepted Russians messages. One missive, sent by Rennenkampf, showed that the First Army was proceeding northwestward toward Königsberg, according to the initial Russian timetable. Rennenkampf was not about to attack the German rear. The second message, from Samsonov, indicated that he was thrusting deeply to the west—in other words, he thought the German Army was in full retreat. Ludendorff could not believe his eyes—the Russian intercepts were almost too good to be true.

Encircling the Russian Center

Fighting continued through August 26 and 27. The Russian right wing, separated from the Russian center, came into contact with Mackensen’s XVII Corps and the I Reserve Corps near Lautern. The Russian right wing was badly beaten and thrown into headlong retreat southward to Olschienen and Wallen, more than 20 miles away. Some Russian soldiers were trapped with their backs to Bossau Lake, and then drowned.

On August 27, François attacked the Russian left near Usdau. Exhausted and starving, Samsonov’s left fell back in disorder. By nightfall, the Russian Second Army’s wings were broken and in retreat. The only thing left to do was to try to extricate his center. Yet Samsonov inexplicably ordered his center to push forward, virtually assuring that it would be encircled and trapped.

At dawn on the morning of August 28, François and his I Corps swung eastward and reached Neidenburg. The door had swung closed. The Russian center—the XIII, XV, and much of the XXIII corps—was trapped. Formations disintegrated, discipline broke down, and the remnants of Second Army became a mob of starving, footsore men stumbling around the dense Prussian forests.

Some units attempted a breakout. Elements of the XIII Corps made a particularly noble effort; the Nevsky Regiment led a desperate evening charge that captured four German guns. But later that night, the XIII Corps soon came to a clearing, and on the other side were manned German machine-gun posts. The open ground became a killing field, well lit by crisscrossing German searchlights. The XIII Corps had had no food or water for two days, but the men mounted a series of frantic attacks to escape the German net. Five times the Russians went forward, only to be raked by chattering machine-gun fire. After the fifth failed assault, the Russians gave up the effort, melting into the surrounding woods. They were later taken prisoner.

92,000 Russians Taken Prisoner

All was lost. Samsonov, ill with asthma and crushed by shame, walked into the woods and shot himself. His body was later found by the Germans. Perhaps 10,000 Second Army men escaped the debacle. Casualty figures were uncertain, because of the countless Russians who perished of wounds in the forest or drowned in the marshes and lakes, but approximately 92,000 Russians were taken prisoner and another 30,000 wounded were added to the total. Some 500 guns were also taken. Hindenburg and Ludendorff became national heroes, but the German public gave little recognition to Colonel Hoffmann, the real architect of victory.

In early September, the German Eighth Army again took on Rennenkampf in the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes. When Rennenkampf finally woke up to the Second Army’s peril, he tried to send aid. It was too little, too late; the nearest First Army unit was still more than 45 miles away. The First Army’s southern wing was dangerously spread out from the rest of Rennenkampf’s forces. By September 2, the mopping up at Tannnenberg was almost complete. Hindenburg turned his attention to Rennenkampf, hoping for another triumph. The German general was helped by the arrival of two corps from the Western Front. The Russians maneuvered well, and Rennenkampf became aware of the danger of being outflanked.

The German Eighth Army and Russian Second Army clashed. To buy some time, Rennenkampf ordered an offensive, a move that actually pushed the German XX Corps back for a few miles. But victory was fleeting. A huge German flanking movement was developing in the south, and to avoid a second disaster there was nothing to do but retreat. Rennenkampf ordered a rapid general withdrawal that was covered by a strong rear guard. The Russian First Army managed to escape, in part because it retreated more rapidly than the Germans advanced.

Tannenberg stands out as one of the very few battles of World War I that was a clear-cut, decisive victory. It could be argued, however, that the unquestioned triumph also sowed the seeds of eventual German defeat. The East Prussian crisis caused many German units that were vitally needed in the west to be hastily transferred to the east. Those troops might have helped defeat France and Great Britain at the Marne. Instead, the Allies stopped the German advance and ensured that the war would become a muddy morass of static trenches. Because the Schlieffen Plan failed in the west, Germany was condemned to four years of bloody stalemate and, ultimately, crushing defeat.

Great article! And readers didn’t need to be amateur WWI historians in order to understand it.

Bravo!