By Kelly Bell

More than 300 years ago Russia was a supine giant convulsing internally from factionalism, making it difficult to resist hostile incursions, until 23-year-old Crown Prince Peter I ascended to the tsarist throne in 1696. A far-sighted young man, Peter the Great, as the world would soon know him, could diagnose issues at a glance and deduce needed crucial reforms. He was equally adept at executing those changes. After quickly establishing himself as absolute monarch he embarked on a crusade to open up his country to the progressive West and hence guide it into a rapidly developing, expanding world.

Peter perceived the domestic resources at his disposal and the benefits to be gained from their exploitation. By exporting flax, hemp, pitch, furs, hides and timber Mother Russia could reap bountiful largesse from international markets thirsting for these commodities. The fly in the ointment was that, despite its gargantuan size, his country was mostly landlocked. Apart from the White Sea port of Archangel, which was closed by ice most of the year, there was no access to international shipping lanes. Along with upgrading his military, Peter desperately needed a seaport on the busy Baltic Sea. First, though, came his armed forces. Russia’s vast reservoirs of natural resources would not be enough, as he made clear in a conference with his top advisors:

“A ruler who has but an army has but one hand, but he who [also] has a navy has both.”

Sweden was his main adversary, so the young Tsar hired army and naval experts from Holland, England, Scotland and Prussia to overhaul Russia’s military. Considering the caliber of his opposite number this was not a situation he dared overlook.

Like Peter, Charles XII was a young man, crowned king of Sweden in 1697 age 15. And like most adolescents, especially those finding themselves in such a position of power, he was impetuous. But he was far beyond his few years in his quick, clear grasp of issues and circumstances and how to address them. And, like Peter, he had a ruthless determination to succeed—just one of their many similarities of personality and ambition.

Charles eagerly, meticulously absorbed a military education in pursuit of his aspiration to match the feats of his illustrious predecessor Gustav II Vasa (known in Europe as Gustavus Adolphus) who had established Sweden as a major power via his battlefield exploits during the Thirty Years’ War. Crowned king at age 17 Gustaphus had imposed Swedish domination over Finland, Lapland, Karelia, Ingria, Estonia, Livonia, western Pomerania, the Baltic port of Wismar and the North Sea bishoprics of Bremen and Verden. By 1697, Charles’ powerful navy controlled the Baltic—and access to commerce for Poland, the northern German states and Russia.

Still, Peter was not intimidated. He aimed to supplant Sweden as the main power in the lucrative Baltic region, but realized he needed a realistic and credible reason to justify opening hostilities in the war this would require. He thought of two.

The first was Ingria, at the northwestern tip of modern-day Russia that had been a source of Russo-Swedish contention for hundreds of years. It was there that Peter intended to construct the future, vital port of St. Petersburg. Since 1617 it had been governed by Sweden, and was a tinderbox of smoldering discontent between its Lutheran rulers and Russian Orthodox citizens, who were eager to be freed from their denominational rivals.

Peter’s second reason was more personal. In 1697, fearing assassination, he had arrived incognito on a visit to Riga on the Baltic coast. Hoping to tour and take copious notes on the harbor’s defensive fortifications he was angered when the city’s Swedish governor refused him access to the waterfront. Taking this affront personally he used it as further justification to commence a campaign of aggression, and in 1699 allied himself with Saxony and Denmark, who were also hostile to Sweden. After spending the rest of that year mobilizing and merging logistics with his new allies he declared war in 1700. The Great Northern War, as the conflict came to be known, would last into 1721 and it would teach Peter to respect his opposite number.

As the fighting began and spread, Charles quickly made a name for himself as a true paladin of the battlefield. His charismatic personality, coupled with his tactical acumen, soon endeared him to his soldiers. As did the fact that he lived, fought, ate and slept alongside them. An unnamed advisor described him as “married to his army.” Charles savored the life of a campaigner, spending almost his entire reign in the field. His renown spread beyond his borders as Britain’s Duke of Marlborough expressed a yearning to join Charles’ command and “learn what I yet want to know in the art of war.”

As the Great Northern War unfolded, Charles wasted no time in wounding his adversaries, crushing the Danes before turning his eager attention to Peter and his ally Augustus, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland. In November 1700 Charles and not quite 9,000 of his soldiers stormed forward out of a blizzard, breaching the fortifications of Narva (just west of modern-day St. Petersburg) and crushing a Russian garrison of 40,000.

A sobered Peter may well have been willing to come to terms at this point, but Charles offered no peace feelers. As a devout Protestant he held his opposite number in the lowest esteem, regarding him a decadent, secular ruler whose domain needed liberating. For the time being, however, Charles felt the Russians were sufficiently cowed to allow him to turn his attention to other, still-unfinished matters. Launching major campaigns in 1702 and 1703 he crushed the Saxons, and then attacked Augustus, forcing him to flee Poland and abandon his throne to Charles’ puppet king, Stanislaw I. But Peter was taking notes, making preparations for a protracted and decisive reaction, a fact he made clear at a summit for his top field commanders: “The Swedes will go on beating us for a long time, but eventually they will teach us how to beat them.”

He commenced dispatching troops to assist Augustus while simultaneously working on his own logistics and recruiting. His determination to avenge the humiliation of Narva moved him to introduce widespread conscription and heavily tax Russia’s Orthodox monasteries—even ordering church bells to be melted down and forged into cannons. He hired western officers to create, train and lead elite corps. Charles would be the first enemy to learn the rueful lesson later thrust upon Napoleon and Hitler—Mother Russia, her resources and climate are formidable.

Peter could—and did—draw upon an essentially endless reservoir of serfs to flesh out his ranks, and was quite willing to absorb staggering losses in order to achieve his aims. The sheer size of the country, as well as its harsh weather, were formidable obstacles for invaders. An ambitious army might easily cross Russia’s seemingly endless border, but it was nearly impossible to overrun. There is simply too much land to conquer, especially when it is blanketed by deep snow and cloaked in killing cold most of the year.

Doubtless cognizant of the military advantages being provided by the Motherland’s size and climate, the young tsar threw himself into anti-Swedish endeavors. In the spring of 1703 he smashed a fly with a sledgehammer by sending a massive army to crush the little fortress of Nyenskans at the mouth of the Neva river. Although a clear case of overkill, his actions may have been justified in light of the offensive’s results. By eliminating this minuscule enclave Peter totally routed the Swedes from the eastern extreme of the Gulf of Finland. He then commenced heavily militarizing this area. These fortifications would soon grow into his capital of St. Petersburg. Emboldened by this latest success, he followed it up by retaking the town of Narva in a grisly battle that ended August 9, 1704.

Charles refused to be discouraged by this setback, and made no effort to alter his strategy and aims. He stuck to his plan to first strike at Russia by neutralizing its ally prior to a decisive confrontation with Peter. In September he launched an attack of such abandon that it knocked the Poles off balance as Swedish invaders rampaged 1,000 miles across their country and into the heart of Saxony, shattering Augustus’ forces and compelling him to sign a humiliating armistice that formally ended his partnership with the tsar. Suddenly stripped of allies, Peter considered abandoning his warrior ways and embracing mediation. This might have made for a fairly positive outcome for Charles because of an unrelated situation.

Since 1701, western Europe had been embroiled in the bloody War of Spanish Succession. Beset by a coalition of resolute enemies, French King Louis XIV was running low on resources of all kinds, especially competent soldiers. Casting about for a mercenary army he noted (along with the rest of Europe) the impressive recent performance of Swedish fighting men. The elderly monarch approached Charles, offering him a deal in which Louis would arrange a cease-fire between Sweden and Russia if Swedish troops would fight alongside the French.

Charles saw no reason to shift his focus from east to west and embroil his armies in a conflict whose outcome either way would offer little profit to Sweden. Besides the lack of a clear motive for accepting the French overture, the youthful Scandinavian monarch could readily perceive Russia’s dire straits. His war against Peter was going well, so why make peace when victory appeared within his grasp? He decided to launch a major offensive and finish off Peter.

Swedish spies had informed him most of western Russia’s population was disillusioned by Peter’s seeming determination to sweep away traditional Russian values. His far-ranging reforms aimed at modernizing the country had not yet produced noticeable improvement, and such dictates as the banning of wearing beards and long coats struck the people as bizarre and invasive. When his Fifth Column operatives informed him these people would greet him as a liberator, Charles resolved to deliver a knockout blow. He would send his armies on a trek across Poland and Lithuania, stabbing into the Motherland’s heart with Moscow as his final objective.

His first task was to gather a force sufficiently sizable for the coming operation, and to secure dependable supply routes. With both these aims in mind he contacted Ukrainian Cossack Chieftain Mazeppa, who was eager to free his land and people from tsarist rule. He led 30,000 cavalrymen, expert in fighting on horseback, into Charles’ encampments. Mazeppa not only provided crucial manpower, but assured his new Swedish ally their combined forces would be adequately nourished from Ukraine’s fertile croplands. Leaving nothing to chance, Charles sent for additional soldiers from Sweden, where governmental officials were bemoaning the war’s drain on their economy and resources.

As the weather warmed in the spring of 1708, Charles bivouacked his command of 35,000 troops at Borisov, 180 miles west of Smolensk. At Riga, 500 miles to the northwest, Count Adam Lewenhaupt waited with another 12,500 soldiers. As he was settling in at Borisov, Charles sent word for Lewenhaupt to join him and bring his crucial supply wagon train. Without waiting for a response Charles impatiently advanced on Peter’s army, only to have it flee eastward. It was a ploy to extend the Swedes’ supply conduit, making it longer and requiring more troops to guard its increased length. Charles saw through this tactic, and halted his army upon reaching the Dnieper, intending to wait for Lewenhaupt. After encamping in and around the city of Mogliev, Charles received a dispatch informing him his reinforcements and supplies were unable to embark because of a paucity of horses and wagons. Lewenhaupt estimated it would be July before he could move out.

This delay could have worked to the invaders’ advantage. The troops were winded and hungry after their already-lengthy advance. Waiting for their reinforcements and supplies would give Charles’ men time to rest and refresh and—considering the date of Lewenhaupt’s arrival was uncertain—perhaps wait out the brutal Russian winter in relatively comfortable accommodations, or even withdraw to the opulent Ukraine, where they could be assured of more-than-sufficient food and yet more recruits. Mazeppa, however, was anxious to join forces with the Swedes and defeat the Russians before Peter learned of what he would regard as treason on the part of the Cossack leader. Despite his misgivings, Charles fatefully let himself be talked into heading south without waiting for Lewenhaupt.

From this point Peter’s innate tactical/strategic skills came through as he dispatched troops to the Ukraine to re-establish Tsarist authority and find a general of auxiliaries who, unlike Mazeppa, was loyal to Moscow. Word of this maneuver spread, and most of Mazeppa’s Cossacks deserted him and aligned themselves with Peter. Although the situation was looking increasingly grim for Charles, he had not yet lost hope because, in early August, Lewenhaupt finally sortied with reinforcements and the supply convoy. This lengthy, horse-drawn line of thousands of wagons, however, was slowed by torrential autumn rains as it passed through Lithuania. By the time it reached Mogilev in mid-September the Swedish army was long gone, the delay having led Charles to conclude the supply train was not coming.

In hopes of catching up with him, the teamsters and reinforcing troops made their best speed, arriving at the Dnieper on about the 20th. At this point, Russian reconnaissance patrols spied the pack train and galloped back with this news to their main force. Setting out to intercept this tempting target with a contingent of 14,500 cavalry, Peter found it encamped outside the riverine city of Lesnaya. Although taken unawares, Lewenhaupt and his sorely outnumbered soldiers fought gamely. After losing more than half his command, Lewenhaupt withdrew under cover of darkness, abandoning the priceless supply cache to the delighted Russians.

By this point Charles had been reinforced by more troops from the Ukraine and a large contingent from Livonia. Expecting Charles’ army to be well supplied, the new arrivals had brought little with them except weapons and ammunition. The massive, multinational forces who had come to fight the Russians found themselves with virtually no food and a brutal winter bearing down on them. Bivouacking east of Kiev, in and around the cities of Romny, Priluki and Lochvika, Charles commandeered numerous billets, turning locals out into the cold. To the misery of the cold and starvation, disease was soon added.

The plague spread through the rat-infested confines of the army’s encampments. Thousands died from illness, starvation and hypothermia. The entire, 10,000-man German contingent deserted and fled to the west in desperation. Respite was slow in coming as the Arctic-like winter dragged on interminably. The incredible cold reached as far south as Italy, freezing the canals of Venice. In May, the Baltic Sea was still covered in ice. The requisitioned area was too small to accommodate Charles’ immense command, so his soldiers pitched lean-tos against the outer walls of the overcrowded buildings, used picks to hack trenches in the frozen ground and slaughtered their horses and mules for food. A Lutheran chaplain later described his parishioners’ suffering:

“We experienced such cold as I shall never forget. The spittle from mouths turned to ice before it reached the ground. Sparrows fell frozen from the roofs to the ground. You could see some men without hands and feet, others deprived of fingers, toes, faces, ears and noses, others crawling like quadrupeds.”

By winter’s end the army of Swedes and their auxiliaries had been reduced to barely half its former strength. The winter had also hurt the Russians, but between their captured caches, intact supply lines and adequate accommodations they weathered the killing cold far better. And unlike Charles, who was hemmed in by hostile forces, Peter was able to send out recruiters to conscript able-bodied young men from the surrounding region to swell his ranks. By April 1709, the Tsarists were ready to re-commence fighting.

Following the ravages of the winter, neither side had enough resources for more than one major campaign. Charles sent repeated messages to his lapdog king in Poland, Stanislaw, to draft as many healthy young Polish men as possible into Sweden’s army and send them to the thawing theater of operations. Some Swedish generals urged Charles to withdraw westward to hasten the link-up with these reinforcements, but while his officers saw this as a redeployment, the young monarch construed it as retreat—a word he could not abide.

Instead, Charles established control over the highway running eastward from Kiev to Kharkov, which was the major thoroughfare from Poland. While this was a sound move for future operations, it did little to replenish and reinforce his army in the short term. Realizing this, he moved east to the town of Poltava, located where the Khatkov road crossed the Vorskla River. This community was essentially a fortified military outpost garrisoned by 4,000 Russians with powerful artillery support. The invaders would have to hurry and neutralize it before Peter, who was certain to be tipped off by Russian couriers out of the town, arrived with his main army.

On May 1 the Swedes began shelling Poltava heavily, but the damage they inflicted was not as telling as they assumed. Despite the towering columns of smoke and leaping flames, the dug-in defenders suffered relatively few casualties. By mid-June Peter’s main force still had not arrived, but the besiegers were running short on ammunition. Erroneously thinking he was seriously hurting his foes, Charles could not figure out how they were still firing back, especially since it was apparent they were themselves scraping the bottom of their own caissons. Using whatever it could as ammo, the town’s garrison resorted to bizarre extremes. Charles was shocked one morning to be struck by a dead cat fired from a Russian cannon, but he soon had plenty to distract him from this draconian measure.

On June 15, mounted reconnaissance patrols informed him the main body of Russian troops, 40,000 strong, were assembling north of Poltava along the eastern bank of the Vorskla. However, Peter seemed reluctant to engage in open combat, only sending out small units to jab at the Swedes. His forbearance likely stemmed from his capture of a Swedish courier bearing news from Poland. This horseman was one of several messengers Stanislaw had dispatched to inform Charles he had not been able to raise any troops to send to the king. Knowing this, Peter likely hoped the invaders, decimated by the Russian winter, would decamp and withdraw. Such a move would have been prudent, but the firebrand young Charles was too proud and arrogant. When the forces occupying Poltava stayed put, Peter prepared for a major set-to.

On June 27, he sent a mounted detachment on a feint across the Vorskla south of Poltava. Charles fell for the ruse and personally led a cavalry unit to meet the enemy at the ford. As Charles arrived, a Russian soldier made one of the luckiest shots in history—shattering the king’s left foot with a musket ball. Charles tried to ignore the gushing wound, remaining in his saddle and shouting orders, but his injury soon overcame him. His soldiers loaded him into a wagon and rushed him to the surgical tent. It was his 27th birthday.

For three days he lay in feverish delirium while his feckless generals took no action, even as the Russians began to deploy and construct fortifications. These redoubts could not be outflanked because the river and its swampy banks were impassable, protecting the rear. In addition, Peter’s just-reinforced command was now double that of Charles’ winter-weakened army. The Tsar well knew that it is easier to defend than to attack, so he was constructing defensive positions, daring the enfeebled, famished invaders to choose between humiliating retreat or to assailing bristling defenses manned by a fresh, well-trained, well-armed, well-fed and huge garrison determined to protect its Motherland.

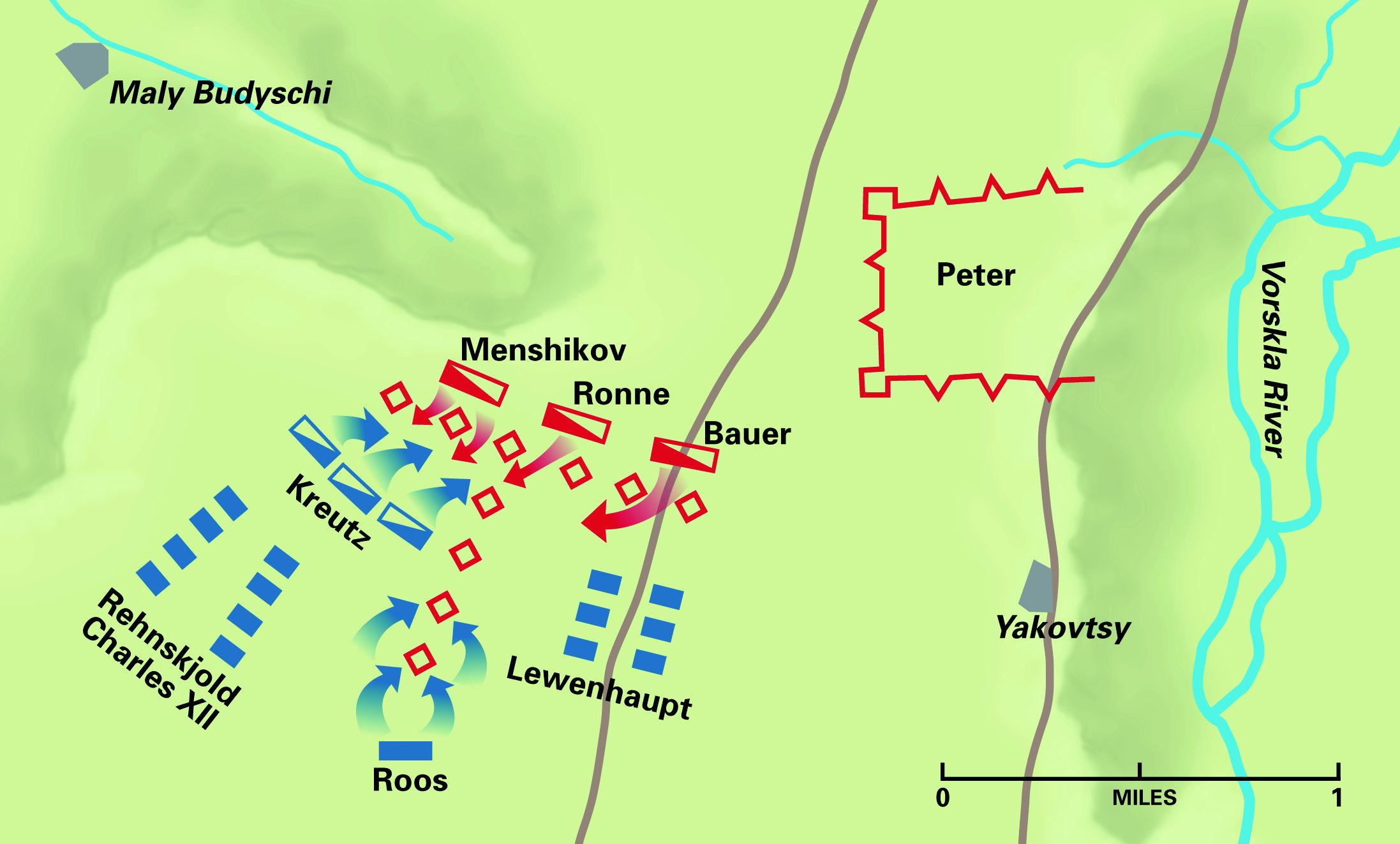

Too weak to stand, Charles realized he was in no fit state for active participation, so he turned over command to Field Marshal Carl Gustav Rehnskjold. The king was now as weakened as the forces he commanded. Still, he imprudently heeded the impatient Rehnskiold’s adjuration, “In the name of God then, let us go forward!” He ordered an attack for dawn on the 13th. The cavalry would charge first, assault and neutralize the redoubts and clear a path for the infantry—who would then scale the palisades and close with the Russians in hand-to-hand fighting. Charles may have been too disoriented from blood loss to realize the impracticality of such tactics versus such overwhelming numbers and it soon went badly wrong.

Summer daybreak comes early at this high latitude, and by 4 a.m. the sun was clear of the horizon. The Swedish infantry was in position, but had to wait as generals Lewenhaupt and Rehnskjold were not finished deploying their cavalry.

While the attackers struggled to get ready, Peter was wrapping up his own preparations. He had spent the hours of darkness erecting yet more redoubts, and was able to complete them because of his enemy’s delay in getting started. Peering through telescopes, the Russians noted how Charles was not yet in position to advance, but the bustling activity in their encampment told Peter the invaders were coming soon, depriving them of the element of surprise.

When the Swedish cavalry charged it pounded into a withering crossfire from 70 cannon entrenched in the middle of the defensive perimeter. Even so, the horsemen managed to rout the defenders, but other elements bogged down as their horses were killed, forcing the mounted troops into a grisly maelstrom of hand-to-hand combat. In the center, Charles was fought to a standstill in front of bristling fortifications, but on his left his horsemen were gaining ground through less-prickly defenses. Peter’s officers urged him to commit his reserves, but he noted how Swedish soldiers were falling in bunches. He could afford to lose men at a greater rate than outnumbered Charles, and would wait and use his still-uncommitted troops to administer the coup de grâce.

Though their ranks were thinning rapidly, the invaders remained dedicated and valiant. Maintaining impeccable discipline they continued to press ahead, but were becoming too scattered to have any hope of success. Desperate to rally his troops, Charles sent Lewenhaupt to charge the Russians’ left flank at 7 a.m. and ordered General Roos, in command of the center, to back off and reassemble what was left of his command. It took Lewenhaupt until 9 a.m. to detach his men and get them to their jumping-off point. Roos did his best, but could not break free from the hellfire pouring from the ramparts. Looking on from those ramparts, Peter saw and diagnosed Roos’ attempt to relocate, and sent fresh reinforcements to counter the maneuver. Chewing a swath through the hapless Swedes, these reserves killed or wounded all but 400 of Roos’ soldiers.

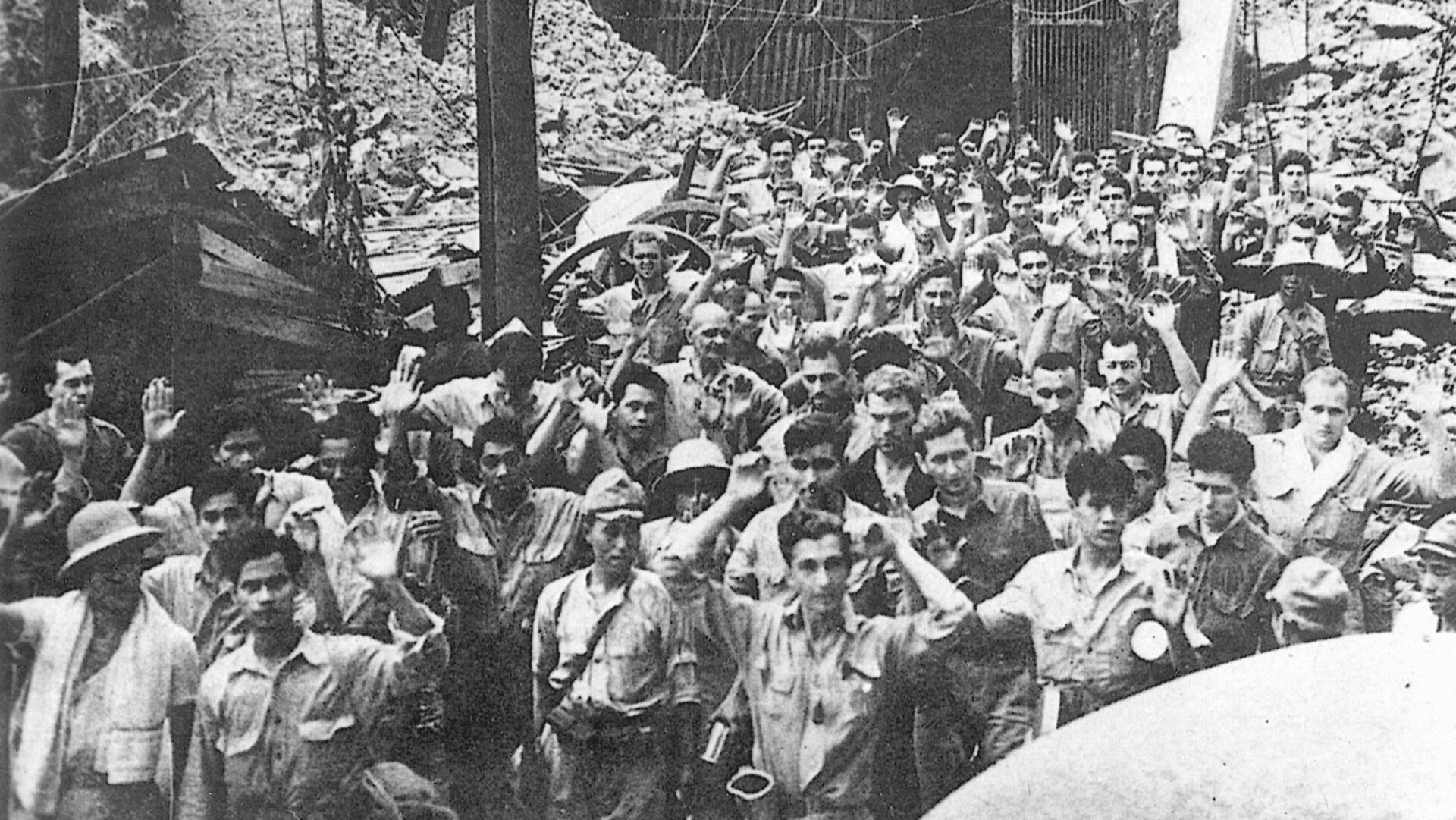

For the first time in his young life, Charles XII was forced to retreat, and Peter was waiting. As the battered Swedes commenced a grudging withdrawal, 30,000 fresh Russian reserves formed up in a phalanx with infantry in the center, flanked by cavalry. To their rear artillery emplacements uncorked a killing barrage over their heads. It was 10 a.m., and the invaders were decimated and exhausted, but still game. Resplendent in their blue jackets and white breeches they trudged resolutely forward into a hail of musketry and grapeshot. Somehow the right wing managed to close with the Russians, but the semi-success was fleeting and expensive. Elsewhere on the battlefield, the Swedes were mauled.

The dwindling left wing ground to a standstill in front of the cannon emplacements, and Peter seized the opportunity—throwing his entire force against the center, slicing the Swedish army in half. Incredibly, Charles’ men kept fighting, launching a cavalry charge against the Russian left. Peter’s field commanders did not wait for instructions, but on their own initiative had their infantry and artillery form up into a square that met the blond horsemen head-on and sent rueful survivors galloping for their lives. They quickly caught up with and passed through the remaining infantrymen, who had thrown down their empty guns and were running for their own lives. By noon the corpse-littered vista was silent.

Incapacitated by his mangled foot, Charles was being borne to the rear on a litter when a cannonball exploded yards away, killing his bearers and most of his personal bodyguard. Miraculously unhurt by the blast, the king was nevertheless almost captured by the pursuing Russians, but a passing cavalryman gave his horse to his liege, who rode it all the way to relative safety in Turkish territory. Behind him almost 10,000 of his men were dead, wounded and captured. Peter lost about 4,500 killed and wounded. His victory would dramatically change the world.

As word of Poltava spread throughout a sobered Europe, government leaders and their people realized the balance of power was permanently altered. A superpower had arisen in the East, and Tsar Peter was its undisputed master. Henceforth his intercourse with other nations would be comported from a position of power. The repercussions of this battle are ongoing. Mother Russia and her resolute people would survive repeated attacks and bloodlettings in coming centuries, maintaining their place as major international players to this day.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments