By Victor Kamenir

Ajubilant British populace joyfully greeted the declaration of war on Germany on August 4, 1914. “I remember when war was declared, going outside Buckingham Palace and cheering with all the crowds as the king and queen came out on the balcony and being frightfully excited and thinking it was splendid that we were going into the war and all the rest of it,” recalled Londoner Angela Limerick.

While most expected a short, glorious conflict, some, like Colonel Knight, commander of the 1st Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, foresaw a different reality. “None of you men will come back nor the next lot nor the next after that nor the next after that again, but some of the next might,” Private F.A. Bolwell remembered Knight greeting reservists reporting for active duty, “But we’ll give those Germans something to go on with, and we’ll give a good account of ourselves.”

Hopes for a quick war died in the mud and trenches, which stretched from Switzerland to the English Channel by the end of 1914. Having captured large swaths of territory on the Western Front, Germany went on a strategic defensive in the West while concentrating its forces in the East, intending to crush Russia first.

Taking advantage of the Allied temporary numerical superiority, Gen. Joseph Joffre, Commander-in-Chief of the French General Staff, in conjunction with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) launched several unsuccessful offensives in the first half of 1915. In response to the severe losses suffered by the small professional pre-war British Army, Lord Herbert Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, launched a massive recruitment campaign to bring volunteers to colors. These “New Army” or “Kitchener’s Army” volunteer divisions soon began arriving in France.

The failed offensives had also depleted British pre-war artillery ammunition stocks. The resulting “Shell Crisis” led to the creation of the Ministry of Munitions. During a conference in Boulogne in June 1915, British Minister of Munitions David Lloyd George and French Munitions Minister Albert Thomas concluded that any significant offensive would require at least 36 divisions advancing over a front of 25 miles supported by at least 1,150 heavy guns. Since required artillery, ammunition, and new divisions would arrive in the spring of 1916, the two ministers advocated postponing the offensive until then.

Undeterred by the shell shortage and objections by senior British officers, Joffre insisted on another push in the fall of 1915. In May an offensive had partially breached the German lines, leading Joffre to believe that a decisive breakthrough, followed by rapid exploitation by mobile reserves, could be attained by a greater application of force—one “Big Push.” Although BEF commander Field Marshal Sir John French disagreed with Joffre, he was obliged to consent in the spirit of political cooperation.

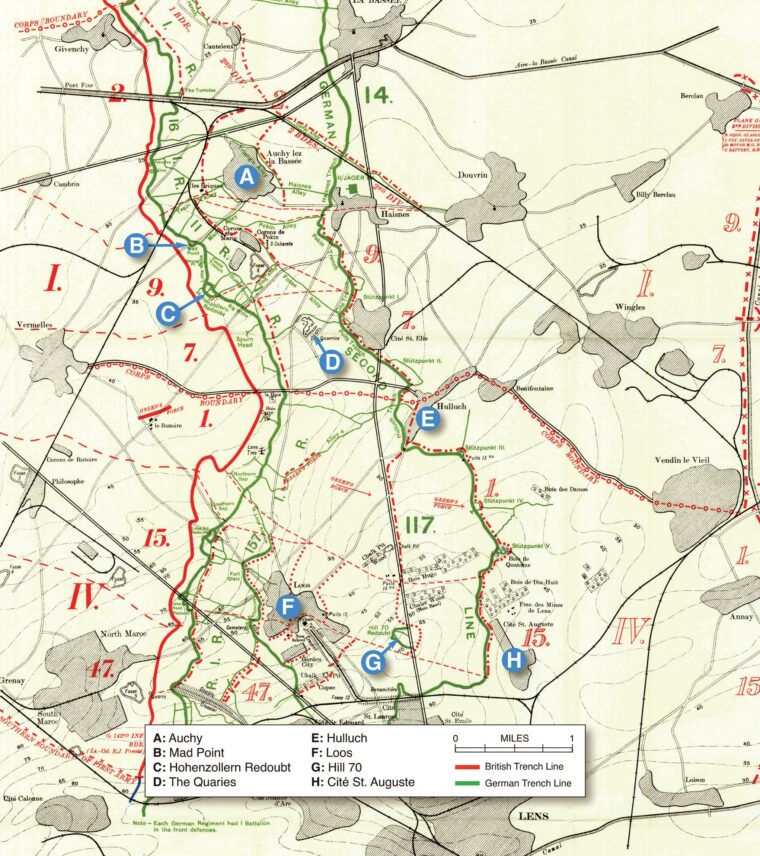

Joffre planned two widely separated offensives: Champagne in the southeast and Artois in the northeast. It was essentially the same offensive as in the spring, but on a larger scale. Four French armies would carry out the main attack in Champagne. In Artois, the mining region of northeast France, the French Tenth Army would assault the Vimy Ridge sector south of Lens. The British First Army would attack along a six-mile stretch between the mining village of Loos (Loos-en-Gohelle) and La Bassee Canal.

After reconnaissance of the region, General Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the First Army, became skeptical of the location of the northeast offensive—several small villages, mines, slag heaps, railroad branches, and mining infrastructure dotted the area, leaving little room for maneuver. Instead, he proposed attacking north of the La Bassee Canal. Despite Haig’s misgivings, he was overruled by French. The two had been good friends serving in India, where Haig loaned French a substantial sum to see him through financial difficulties. But now there was an undercurrent of animosity in their relationship.

The formidable German positions were an in-depth system of primary and fallback trenches, machine-gun nests, and extensive wire obstacles—all linked by communication trenches. Tunnels in the slag heaps held elevated observation and fighting positions. Fortified strongpoints (stützpunkt) bristled with machine guns overlooking the crater-pocked no-man’s-land. Planes from the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) observed the Germans constantly improving defenses, including establishing second and third defensive lines.

The village of Auchy in the north and Loos in the south anchored the first German defensive positions. To the southwest of Auchy, on a slight rise, lay a powerful defensive works called Hohenzollern Redoubt (Hohenzollernwerk). Aerial photographs showed the redoubt as a spider web of trenches set up for all-around defense. Behind it was a fortified pit head, Fosse 8, and a slag heap (crassier) called the Dump.

The second German defensive line ran from La Basse in the north to Hulluch in the center to the hamlet of Cité St. Auguste east of Loos. Northwest of Hulluch, in front of the hamlet Cité St. Elie, was a fortified node at The Quarries. The ground between Loos and Cité St. Auguste gently sloped up to 70 feet, with strong defensive points at Hill 70, Chalk Pit (a wood), and Puits 14bis (a coal mine). An interlinking chain of machine-gun positions on reverse slopes was placed out of direct observation and range of British field artillery. British observation aircraft reported wire obstacles up to 30-yards across in front of the second defensive line. Farther back, German artillery kept up harassing fire against British positions and roads to the rear of them.

The German Sixth Army under Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria faced the upcoming British onslaught. The VII Army Corps—14th and 117th Infantry Divisions—defended the German north flank between La Bassee and Hulluch. The IV Army Corps—7th, 8th, and 123rd (7th Royal Saxon) Infantry Divisions—held the Loos sector. General Haig’s First Army consisted of I, III, and IV Corps, each of three divisions. Deployed north to south were the 2nd, 9th, and 7th Divisions of the I Corps and the 1st, 15th, and 47th Divisions of the IV Corps.

Haig assigned the III Corps to conduct a diversionary attack at the village of Bois-Grenier, some eight miles north of La Bassee, supporting the main assault by the I and IV Corps. He initially planned to advance with two divisions of each corps, keeping the third division in reserve. After Sir John French promised Haig reserves of two newly arrived New Army divisions, the 21st and 24th, from the XI Corps, Haig decided to attack with all six of his divisions in line. He asked French to subordinate the two divisions directly to him, but French believed they were best used the next day and kept the reserve formations under personal control.

Haig’s modified plans called for his divisions to attack in successive waves of infantry brigades moving forward in timed intervals. One field artillery brigade would support every two infantry brigades, with heavy artillery conducting counter-battery fire. Once infantry went forward, artillery fire would shift deeper into German defenses. Estimates of guns available to Haig vary from 466 to more than 800. In any case, they were woefully inadequate for the task. The ubiquitous QF 18-pounder field guns and similar calibers focused on damaging forward German defense, especially the extensive wire obstacles. To try to disrupt German logistics, Haig had 24 heavy naval guns, adopted for field service and manned by Royal Marines, 24 massive BL 60-pounders and three BL 15-inch howitzers.

To compensate for the insufficient artillery, Haig was permitted to employ Chlorine gas for the first time in British military history. This was despite the outrage expressed by France and Britain at the German use of gas—resulting in more than 1,000 deaths and some 7,000 injuries—at the Second Battle of Ypres on April 22.

For that task, special companies of Royal Engineers accumulated 5,100 metal cylinders containing 140 tons of gas. Since German gas masks were believed to be only good for about 30 minutes, smoke rounds would be intermixed with the gas to create an impression of a larger volume—an attempt to compel the Germans to wear their masks past the point of effectiveness.

In case of a breakthrough, two cavalry corps had orders to exploit the gap—but they had not been given any objective beyond advancing in the general direction of the Belgian border some 30 miles away. The date of the offensive, postponed several times to stockpile enough artillery shells for the task, was finally set for September 25.

The first phase would be a Royal Flying Corps bombing campaign. At this stage of the war, pilots had to fly low—exposing themselves to ground fire—to have any hope of a direct hit. As a result, bombing by either side caused little damage.

The primary role of the RFC was photo reconnaissance and artillery spotting utilizing wireless communications. Superior German Fokker fighter planes, called the “Fokker scourge” by the British—firing synchronized machine guns through the propeller arc—posed a significant threat to British planes. Bad weather hampered aircraft performance on both sides.

The Allied preparations did not escape notice by German intelligence. British prisoners reported heavy artillery arriving at the front, and work on saps extending into no-man’s-land was observed from German positions. By September 21, when the British commenced preliminary artillery bombardment, Prince Rupprecht was convinced that an attack was imminent. However, he expected the main allied push to come from the French Tenth Army in the area of Souchez and the Vimy Ridge.

Despite prodigious shell expenditure, German trenches and wire obstacles remained largely intact. The four-day artillery barrage showed the Germans where the new Allied offensive would occur—only the date was unclear. Haig anxiously monitored weather reports, fretting whether there would be sufficient wind in the morning of September 25 to carry gas toward German trenches. The evening before, he received a forecast of adequate wind conditions and gave final approval. Overnight, work parties removed overhead cover from saps and linked them by trenches at the ends closest to German positions.

While those preparations were being made, Sir John French moved the advance party of his headquarters from St. Omer to Chateau Philomel outside Lillers, some 15 miles behind the British front lines. Until his full headquarters were in place, French’s only means of communication was a civilian telephone system. At the same time, French ordered the 21st and 24th Divisions, followed by the Guards Division, to move to Noeux-les-Mines and Beuvry, less than 10 miles behind the front lines, where they arrived exhausted around 6 a.m. the following day.

In a light drizzling rain at 2 a.m. on September 25, British infantry brigades began moving from the rear trenches to the jump-off positions in the sap trenches. Clutching their bayonet-tipped rifles, the men anxiously watched Royal Engineers make final adjustments on the gas cylinders. Narrow lead pipes, held in place by sandbag revetments, snaked over parapets toward the Germans from metal cylinders dug in vertically in the trenches.

At 5:50 a.m., Royal Engineers opened the stopcocks on Chlorine cylinders. At the same time, British artillery increased the fire tempo as the wall of yellow-greenish gas up to 80-feet high slowly drifted toward German positions. The gas release signified to the German command that an attack was imminent, and defenders rushed to man the trenches. German artillery came alive, raining shells on the British lines to disrupt the attack.

In the area of the IV Corps, the wind largely pushed the gas cloud forward while barely moving or blowing back toward British positions in the I Corps sector. “At 6:20 a.m., the wind changed slightly, and the gas and smoke began to drift back. The alarm was given, and gas helmets were at once adjusted,” remembered 2nd Lt. Sidney Major from 1/18th London Irish Rifles, “A few men, who were not quick enough in adjusting their masks, fell to the floor of the trench, writhing and choking in an agony of suffocation as the chlorine worked on their lungs.”

At the 6:30 a.m. H-Hour, long whistle blasts sent leading echelons of gas-masked British infantry over the top from sap trenches. On the far left of the I Corps, the attack of the 2nd Division quickly stalled in the face of heavy German machine guns and artillery fire.

The 9th (Scottish) Division advanced in the center of the I Corps against the heavily fortified Hohenzollern Redoubt. Although taking withering fire, the leading Scottish battalions leaped into German trenches. With bayonets and hand grenades, the Scots overran the redoubt against determined German opposition around 7 a.m. and continued to Fosse 8 pithead. Reserve units had to run the gauntlet of flanking fire from a German stützpunkt called Mad Point just outside of Auchy, and the 8/Black Watch Regiment took particularly severe casualties.

One battalion, the 8/Gordon Highlanders Regiment from the 26th Brigade, penetrated 1,000 yards farther to take The Dump slag heap by 8 a.m. At the cost of the 11/Royal Scots Regiment decimated by machine gun fire, the 27th Brigade moved up to support what appeared to be a breakthrough.

On the left flank of the 9th Division, the wind blew the gas back to the British lines and being heavier than air, it settled into the trenches. Cylinders destroyed by German artillery fire flooded the area with more gas, incapacitating hundreds of Scottish infantrymen. “Piper Daniel Laidlaw, King’s Own Scottish Borderers, seeing that his company was somewhat shaken from the effects of gas, with absolute coolness and disregard of danger, mounted the parapet, marched up and down, and played the company out of the trench,” reported the London Gazette, “The effect of his splendid example was immediate, and the company dashed out to the assault. Piper Laidlaw continued playing his pipes till he was wounded.”

When the 28th Brigade pushed into the open through the gas clouds, it was devastated by machine gun fire and thrown back. Only some 70 men from the 6/King’s Own Scottish Borderers Regiment made it back to their trenches unscathed. Another attempt by the 28th Brigade at noon similarly failed.

In the sector of the 7th Division, “…the gas went whistling out, formed a thick cloud a few yards off in no-man’s-land, and gradually spread back into our trenches. The Germans, who had been expecting gas, immediately put on their gas helmets…,” remembered Lt. Robert Graves of Royal Welsh Fusiliers, “Then their batteries opened on our lines. The confusion in the front trench must have been horrible; direct hits broke several gas cylinders, the trench filled with gas, and the gas company stampeded.” More than 100 men from the 1/South Staffordshire Regiment were incapacitated before the battalion left its trenches.

Machine guns reigned supreme over the battlefield. Robert Graves saw a lieutenant urging his platoon to continue the advance. When the men did not respond to his command, the lieutenant shouted, “You bloody cowards, are you leaving me to go alone?” His wounded platoon sergeant reportedly replied, “Not cowards, sir. Willing enough. But they’re all f**king dead.”

Two battalions, the 1/South Staffordshire Regiment and the 2/Royal Warwickshire Regiment, suffered 70 percent casualties before coming to grips with the Germans. One horse artillery battery was deployed forward of British trenches, and two field artillery batteries were set up immediately behind the line to support the advance with direct fire. By 9:30 a.m., the 7th Division breached the first German line and pushed to The Quarries northwest of Hulluch, encountering uncut wire in front of the second German trench line. While the men with wire cutters struggled to cut their way through the obstacles, German machine gun fire rained on soldiers pinned down in the open.

Gas drifting into British trenches delayed the 1st Division on the left flank of the IV Corps. In its sector, German wire remained largely intact, and the British suffered heavy casualties while attempting to break through. By 7:30 a.m., the smoke and gas cleared, and German artillery and machine-gun fire raked the exposed British troops. Suffering heavy losses, the 1st Division reached the midpoint between the German lines by 9 a.m. but could not advance farther.

In the center of the IV Corps, the gas was slow to advance and even blew back into British positions, causing casualties among the advancing troops of the 15th (New Army Scottish) Division. As the men emerged from the gas cloud, German machine-gun fire scythed into them, causing heavy losses. Pressing forward, some Scottish battalions wearing their distinctive kilts breached the first German defensive line and entered Loos from the north. In house-to-house fighting with bayonets and hand grenades, the 15th Division cleared Loos by 8 a.m. Heavy officer casualties led to a communication breakdown and disorder among intermixed units. Driven on by surviving officers and NCOs, the Scots pushed the Germans from Hill 70 and began advancing down the eastern slope. Murderous machine gun fire from the second German line gutted the disordered battalions, and by 10:30 a.m., the attack faltered. Reserve brigades moved up to dig in on the western slope of Hill 70.

On the right flank of the IV Corps, following a steadily moving gas cloud, the infantry of the 47th (London Territorial) Division reached the German positions, suffering minor casualties. “The heads of the attackers were shrouded by large blue-gray flannel gas masks and through the large, round, goggles, intent eyes stared, while the projecting outlet of the mouthpiece rose and fell as the men moved and breathed,” wrote Sidney Major, “The cowled figures, with rifles and bayonets ‘at the ready’ hung about with picks, shovels, bags and bombs and other impediments—exaggerated to giant size by the effect of the smoke and gas—presented a fearsome spectacle and might well strike terror into the stoutest heart as they pressed forward.”

As the 1/18th London Irish surged out of their trenches, Rifleman Frank Edwards, captain of the battalion’s football team, tossed a football into no-man’s-land. Kicking the ball ahead, Edwards and his comrades advanced toward the Germans. Hit in the thigh, Edwards, who became known as the “Footballer of Loos,” was pulled back to the rear and survived the war. His football was later recovered in front of German wire entanglements and is currently on display in the regimental museum.

The artillery bombardment damaged the wire obstacles south of Loos sufficiently, allowing the British infantry to clear the first line of trenches. Apprised of the situation, Rupprecht sent all his reserves to General Friedrich Sixt von Armin’s beleaguered IV Corps and requested more from higher command. By 7 a.m., the Germans took back most of their initial positions, but the 47th Division retained possession of the Double Crassier and the Loos Crassier slag heaps. In the afternoon, the German 178th Regiment (13th Royal Saxon) recaptured Hill 70. Another determined German attack took back a large part of the Hohenzollern Redoubt. The Germans launched multiple local counterattacks during the night, keeping the British off balance. In one incident, a German assault party trapped a small group of soldiers from the 27th Brigade, 9th Division, including brigade commander Brig. Gen. Clarence Dalrymple Bruce, in a dugout. Hand grenades tossed into the dugout killed several men and rendered others, including the general, unconscious. General Bruce became the first British general taken prisoner in World War I.

Hand-to-hand fighting in trenches was brutal as men grappled in the mud with bayonets, entrenching tools, and hand grenades. Dug at sharp angles to minimize casualties from shelling, trenches created a labyrinth of deadly tight spaces. Blindly rushing around a corner was surely met with certain death. Hand grenades, or hand bombs, were invaluable in clearing out pockets of resistance. Although carrying less explosive, German stick grenades could be thrown farther, proving superior to their heavier British counterparts. At this stage of the war, the British industry still needed to ramp up grenade manufacturing, and many British bomb throwers still used bombs made from tin ration cans packed with bits of metal and explosives.

Not yet aware of the grievous losses, Haig was encouraged by the news of multiple penetrations of the first German defensive position. With his reserves fully committed by 9 a.m., Haig sent an aide by car to Chateau Philomel to request Sir John French to release the reserves from the XI corps. Apprised of the situation, French dispatched the 21st and 24th Divisions forward. Delayed by the roads targeted by German artillery and ambulances full of wounded streaming west, the two New Army divisions reached Haig in the early afternoon. In their place, French moved the Guards Division to Noeux-les-Mines, which reached the town around 8 p.m.

At 12:45 p.m., the French Tenth Army attacked south of Lens in the area of Vimy Ridge and Souchez. Although the French made initial progress, their attack failed in the late afternoon.

Although Haig did not have a clear picture of the situation, he felt another attempt the next day could breach the second German defensive line, and ordered a renewed offensive at 11 a.m. on September 26. Because of bad weather, the Royal Flying Corps could not provide accurate information about the second German defensive line.

Marching to the sound of the guns in the darkness and pouring rain, Private William Walker slogged toward the front among the 13th Northumberland Fusiliers, “Vivid wicked flashes could be seen, and bright dazzling balls of red, green, and yellow illuminated the flattish land in front,” Walker remembered, “We tramped on; the jingling of our equipment, the squelching of boots in the mud, the labored breathing of weary men, an occasional curse, was like an obbligato to the thunderous storm of war that surged around us.”

In the late morning of September 26, the untried 21st and 24th Divisions received orders to attack without a specific objective other than general move forward. At 11 a.m., amid great confusion, four battalions from the 72nd Brigade of the 24th Divisions entered the killing ground in front of the second German defense line west of Hulluch. Swept by withering fire, the Brigade could not overcome the wire obstacles and fell back, losing all three battalion commanders. Private Walker remembered seeing a British field artillery battery deploying forward obliterated by German artillery fire, “There did not seem to be anything but brown dust and rubbish left.”

Pinned down, many disordered detachments were unable to retreat and were either wiped out or taken prisoners. The Germans took over 500 men from the 24th Division prisoner.

The 21st Division suffered heavily as well. Brigadier General Norman Nickalls, commander of its 63rd Brigade, was shot attempting to rally his shaken men. When the Brigade pulled back, Nickalls’ body was left behind and never recovered. At 1:30 p.m., Haig called off the futile attack.

Needing fresh troops, around 4 p.m., Haig asked French to place the Guards Division under his command as well and received approval. During the night, the three brigades of the Guards Division and dismounted troopers of the 3rd Cavalry Division relieved the 15th, 21st, and 24th Divisions at Loos and Hulluch.

Exhausted troops spent a miserable night in the pouring rain in trenches overflowing with mud. “We spent it getting the wounded down to the dressing station, spraying the trenches and dugouts to get rid of the gas, and clearing away the earth where trenches were blocked,” wrote Lieutenant Graves, “The trenches stank with a gas-blood-lyddite-latrine smell.”

In the afternoon of September 27, the 3rd Guards Brigade attacked Hill 70 but was thrown back with heavy casualties. The 2nd Guards Brigade fought through Chalk Pit and Chalk Pit Wood before being stopped at Bois Hugo copse, Hulluch, and Cité St. Augustine.

Rudyard Kipling’s son John, an 18-year-old lieutenant in the 2/Irish Guards who had landed in France barely a month before, was lost and believed killed at Bois Hugo. The Kiplings searched for their son for years, but his remains were not identified until 1992 and confirmed in 2015. He is now buried in St Mary’s ADS Cemetery.

Despite failure by the 21st, 24th, and Guards Divisions, Sir John French was not ready to call off the offensive, ordering the 12th (Eastern) and 46th (North Midland) Divisions to move down from Ypres to Loos.

While the British prepared for another try, the Germans launched a series of counterattacks, recovering most of the trenches around Hohenzollern Redoubt by October 3 and retaking Fosse 8 by October 8. With the exception immediately east of Loos, both sides returned to their starting positions. The French offensive in Champagne was also a bloody failure.

In preparation for another attack, Royal Engineers placed 3,170 gas cylinders facing the Hohenzollern Redoubt sector. At 11:30 a.m. on October 12, clouds of gas again began drifting toward German positions, followed by bombardment by more than 400 guns, followed by more gas. Again, the gas largely settled down; instead of moving and advancing British men, soldiers immediately came under heavy fire.

At 2 p.m., a British infantry attack began. The 1st Brigade from the 1st Div attacked from 300 yards away between Loos and Hulluch, but only limited damage was done to the wire obstacles, and the attack was stopped. British officers, disregarding their safety again and again, rallied depleted battalions and urged them forward, leading to disproportionate officer casualties. Lt. Col. Angus Douglas-Hamilton of the 6/Cameron Highlanders led four attacks against Hill 70, after which his battalion was reduced to 50 men. He led them forward again the fifth time and fell mortally wounded.

“The gas hung in a thick pall over everything, and it was impossible to see more than ten yards. In vain, I looked for landmarks in the German line to guide me to the right spot, but I could not see through the gas,” wrote 2nd Lt. George Grossmith from the South Staffordshire Regiment to his fiancé, “…Men were disorganized and walking in the direction of the German trenches, looking like ghouls in their gas helmets…We reached the German wire, only to find it intact.” Halted before the Hohenzollern Redoubt and Fosse 8, the 46th (North Midland) Division suffered more than 1,200 casualties. In two companies of 1/5 South Staffordshire, every single man was killed or wounded.

The 12th (Eastern) Division attacked between the Quarries and Hulluch. One battalion, the 6/Buffs, lost more than 400 men within the first few minutes, falling back after advancing 100 yards. The 35th Brigade, braving a firestorm, captured a small foothold in the Quarries but could advance no further. Sporadic fighting continued until 8 p.m. but gradually died down.

French attacks in the Champagne and Vimy Ridge sectors also failed, and Joffre called off the Artois offensive on October 15.

Having failed to achieve a breakthrough, the BEF suffered close to 60,000 casualties, including 7,766 killed, with the Regular army units hit particularly hard. Four divisions lost more than 5,000 men each, and 51 battalions suffered more than 300 casualties. Although more than 2,600 British soldiers were incapacitated by their gas, fewer than 10 succumbed to it. Leading from the front, British officer casualties were grievous. Three division commanders, three brigade commanders, and 29 battalion commanders were killed, and a division commander was taken prisoner. Company-grade officers died in the hundreds. The loss of so many general officers led the British High Command to order that they not visit the front: “no staff officer was to go nearer to the trenches than a certain line.”

More than 20,000 British losses came from the 45 Scottish battalions which took part in the battle. The “Dundee’s Own,” the 4th Battalion of the famous Black Watch Regiment, suffered 19 officers killed or wounded out of 20, as well as 230 out of 420 enlisted men. Almost every family in Dundee lost someone.

But the losses didn’t break the British spirit. The 1st Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, which lost 489 men at the Battle of Loos, cheered upon discovering they were returning to the trenches. A photo of the smiling Lancashire soldiers became so popular it was sold as a postcard in Britain.

German casualties in the Battle of Loos were substantially less, at around 26,000. While it was a tactical victory, it was a costly one. Similar to the British, some of their units were decimated. The 117th Infantry Division lost 6,572 men killed or wounded out of almost 8,000 at the start of the battle.

After the battle, Haig was highly critical of Sir John French, blaming him for mishandling reserves. The resulting political fallout led to French’s resignation and the appointment of Haig to command the BEF.

Multiple causes contributed to the British costly failure in their largest offensive of 1915. Suffering from a dire shortage of ammunition, British artillery failed to suppress German machine gun and artillery positions and defensive works, leaving wire obstacles largely intact. Inclement weather prevented the British Royal Flying Corps from providing accurate observation for the artillery. The tight confines of the battlefield limited maneuver, forcing British divisions to launch successive futile frontal attacks.

Despite all the sacrifices, courage, and expenditure of lives and resources, the British command failed to learn from their mistakes, resulting in another bloodbath at the Battle of Somme in July 1916.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments